Abstract

A microfluidic device utilizing magnetically activated nickel (Ni) micropads has been developed for controlled localization of plasmonic core-shell magnetic nanoparticles, specifically for surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) applications. Magnetic microfluidics allows for automated washing steps, provides a means for easy reagent packaging, allows for chip reusability, and can even be used to facilitate on-chip mixing and filtration towards full automation of biological sample processing and analysis. Milliliter volumes of gold-coated 175-nm silica encapsulated iron oxide nanoparticles were pumped into a microchannel and allowed to magnetically concentrate down into 7.5 nl volumes over nano-thick lithographically defined Ni micropads. This controlled aggregation of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles by an externally applied magnetic field not only enhances the SERS detection limit within the newly defined nanowells but also generates a more uniform (∼92%) distribution of the SERS signal when compared to random mechanical aggregation. The microfluidic flow rate and the direction and strength of the magnetic field determined the overall capture efficiency of the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform. It was found that a 5 μl/min flow rate using an attractive magnetic field provided by 1 × 2 cm neodymium permanent magnets could capture over 90% of the magnetic core-shell nanoparticles across five Ni micropads. It was also observed that the intensity of the SERS signal for this setup was 10-fold higher than any other flow rate and magnetic field configurations tested. The magnetic concentration of the ferric core-shell nanoparticles causes the SERS signal to reach the steady state within 30 min can be reversed by simply removing the chip from the magnet housing and sonicating the retained particles from the outlet channel. Additionally, each magneto-fluidic can be reused without noticeable damage to the micropads up to three times.

INTRODUCTION

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a phenomenon that can enhance the spontaneous Raman scattering signal 106–1014 times using plasmonic noble metals, typically Au, Ag, or Cu.1,2 Non-aggregative colloidal-based SERS detection assays struggle to provide signal stability due to the random and dynamic distribution of nanoparticles when in colloidal suspension.3 Additionally, un-aggregated solid colloids fail to provide sufficiently enhanced SERS signals using red or IR excitation sources due to large gaps among SERS-active nanoparticles that prevent plasmons from coupling between particles.4,5 As a result, while homogeneous, this approach cannot generate highly sensitive surface enhanced Raman signals. The high sensitivity of the SERS signal is primarily determined by the aggregation of nanoparticles.6,7 Electromagnetic enhancement effects dominate over chemical enhancement and are a function of the spatial positioning of Raman-activated molecules.8 Etchegoin and Le Ru used a finite element model to simulate the enhancement factors (EF) of two colloidal gold nanoparticles with an electromagnetic enhancement factor (EF) of approximately 108 when the gaps between the nanoparticles were 2 nm. The EF value could be influenced by an order of magnitude due to a slight change of the gaps.9 Moreover, forming clusters of nanoparticles can promote a significant “hot spot” enhancement for triggering high SERS signals.

To improve upon the reproducibility of forming nanoclusters within microfluidics, both chemical and physical particle aggregation approaches have been investigated. Chemical aggregation can be achieved by liquid ionic modulation using salts, or through nanoparticle functionalization by conjugation to sensing ligands such as aptamers or antibodies.10–13 Often, salt-based aggregation of nanoparticles produces irregular hot spots and is not easily reversible. Physical aggregation includes the clustering of nanoparticles, typically in microchannels, through optical,14 electrical,15 mechanical,16 and magnetic trapping to generate hot spots. The physical approach is able to localize particle aggregation in specific areas to improve the reproducibility of SERS detection. However, some of these approaches, such as micro-to-nanochannel fabrication, require complex nano- or microstructure fabrication and are often very expensive to produce.17 For example, though Wang et al.18,19 fabricated micro-to-nanochannels capable of reproducibly aggregating nanoparticles at micro-to-nano junctions, this device was hindered by the fact that the process had a low micro-to-nanochannel yield, and was very expensive to produce, and each channel was “one time use only.”

As an alternative to these approaches, Zhang et al.20 and Marks et al.21 designed functionalized magnetic nanoparticle pairs as “targets” and “probes” for molecule detection through magnetic trapping for SERS detection using clusters. By integrating microfluidic devices with magnetic trapping, one can potentially provide a continuous process. Magnetic trapping in a microfluidic is a process that can be controlled outside the microfluidic. A magnetic field can be applied outside of the microchannel, and the magnetic particles inside the microchannel can be trapped at a specific region and released. Therefore, the magnetic trapping process in a microfluidic channel can potentially be used for applications such as cell sorting or point-of-care detection. Adams and Tom Soh22 developed a microfluidic based cell-sorting platform for multiple cell separation using magnetophoresis. The magnetic force was determined using different architectures of ferromagnetic strips so that multiple target cells could be separated. Moreover, the microfluidic trapping platform can be applied in aptamer selection. Qian et al.23 mixed streptavidin-modified magnetic particles with an ssDNA library, and magnetic particles were trapped when they pass through magnetic area in microchannel. Aptamers have highly specific binding affinity for their target molecule so that the target aptamer for streptavidin could be selected using the magnetic trapping platform. The magnetic trapping platform was also effectively used to reduce contamination including enhancing the reproducibility and minimizing the exposure for biological and chemical hazards.24

In this paper, a novel microfluidic device with magnetically activated Ni-micropads that can aggregate magnetic SERS-active core-shell magnetic nanoparticles on them was developed. The Ni-micropads are constructed by a planar 5 × 40 array. Five of them are located inside the microchannel. Moreover, the thickness of micropads is on the nano-scale so that the magnetic properties of Ni-micropads can be determined and adjusted by using an external permanent magnet. Once the magnetic field of the outer magnetic micropad is induced, the magnetic field would transport to the inner micropads and trigger their magnetic properties in order to create a magnetic field in microchannel.25 The SERS-activated magnetic particles can then be captured, housed, and accumulated onto the Ni-micropads in microchannel. As a result, SERS could be used to probe, sense, and monitor the nanoparticles and any biomarkers attached to them as they are magnetically trapped on these Ni-micropads.

MATERIALS AND INSTRUMENTATION

Fabrication of the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform

Our magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform was composed of three parts: (i) a microfluidic channel for the injection of the sample fluid containing nanoparticles, (ii) an Ni micropad array for capturing and aggregating the SERS-active core-shell magnetic nanoparticles on them (forming locations of increased electron density at the particle interstices called “SERS hotspots”), and (iii) a pair of external neodymium magnetic bars for inducing and generating magnetic fields around the magnetic micropads.

The microfluidic channel was fabricated by commonly used soft lithography techniques.26,27 The mold for the microchannel was constructed from SU-8 2075 on a silicon wafer. The microfluidic channel features were 100 μm in width, 2 cm in length, and 100 μm in height. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer was mixed at a 10:1 ratio with the curing agent (Sylgard 184 kit, Dow Corning), poured over the silicon wafer mold, and cured for 2 h in a 65 °C oven, thus transferring the pattern from the mold to the PDMS chip substrate.

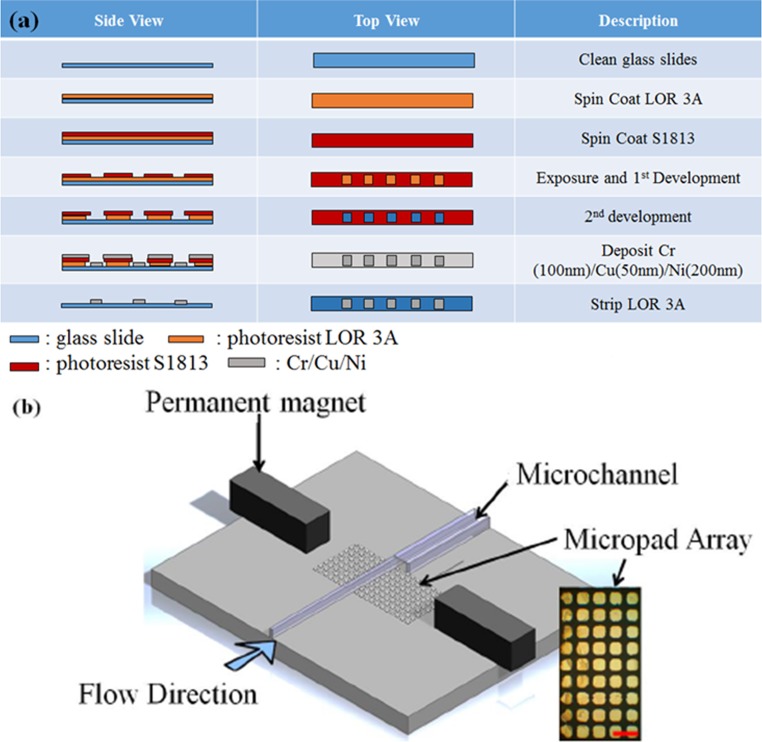

A planar 5 × 40 array of Ni micropads were deposited by E-beam deposition, where the dimension of pad is 50 μm in width, 50 μm in length, and 200 nm in thickness. The photolithography process for fabricating the Ni pads is depicted in Fig. 1(a). Glass slides were spin-coated with lift-off-resist LOR 3A and S-1813 at 750 nm and 1.3 μm, respectively. After exposure to UV light and developer, the patterns of the micropad array were transferred onto the glass slides. A 100 nm-thick chromium and 50 nm-thick copper were then deposited onto the micropad array pattern as an adhesion layer. Finally, 200 nm-thick nickel was deposited as a third layer to serve as the magnetic response layer. After deposition, the whole glass slide was placed into a LOR 3A resist stripper at 80 °C in order to completely remove the entire photoresist layer.

FIG. 1.

Magnetically activated Ni-patterned microfluidic device showing (a) fabrication of the micropad array on the platform; (b) schematic diagram of the magnetic platform, composed of a micromagnet array, a microfluidic channel, and a permanent magnet. The inset picture is the micromagnet array. The size of each pad is 50 μm ×50 μm (scale bar is 100 μm).

To construct the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform, the PDMS channel and a glass slide containing the micropad array were bonded by an O2 plasma treatment. A NdFeB magnet and a 3D printed holder, which were printed by a Perfactory® Micro Advantage 3D printer, were encased around the microchannel to induce and transport the magnetic field inside the microchannel, thereby allowing the field from the permanent magnets to propagate down the nickel pads.

SERS-active core-shell magnetic nanoparticles

The 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA) Raman reporter functionalized core-shell magnetic nanoparticles were purchased from nanoComposix. A schematic diagram of their multilayered structure is depicted in Fig. 2(a). TEM (JEOL 1010 Transmission Electron Microscope) images of silica coated iron particles before gold coating are shown in Fig. 2(b), demonstrating that the average iron magnetite core particle diameter is ∼17 nm and the SiO2 shell is ∼110 nm. The third shell layer was composed of Au and approximated to be 48 nm thick using a Thermo Fisher X Series 2 ICP-MS. The SEM image in Fig. 2(c) shows that the average total diameter of the nanoparticles was approximately 175 nm. The particles were kept in Mill-Q with a zeta potential of -44 mV and a hydrodynamic diameter of 188 nm as determined by a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS.

FIG. 2.

Construction of 4-MBA functionalized core-shell magnetic nanoparticles: (a) schematic diagram of the magnetic core-shell nanoparticles, which are composed of (i) an iron core (17 nm), (ii) an SiO2 layer (110 nm), (iii) a gold shell (48 nm), and (iv) a Raman reporter dye molecule (4-MBA); (b) the structure of Raman reporter 4-MBA, (c) TEM images of silica coated iron before gold coating; and (d) SEM images of the core-shell magnetic nanoparticles after coating with gold and functionalization with 4-MBA.

One of the most prominent vibrational modes of the 4-MBA Raman reporter is observed as a peak located at 1075 cm−1 corresponding to aromatic ring breathing.28 The magnetic trapping efficiency of the platform was initially determined by monitoring the variation in both peak intensity and peak area of the 1075 cm−1 Raman band of the inlet and outlet nanoparticle solutions. This same vibrational mode, 1075 cm−1, was used for contrast in the Raman maps used for characterization of the localization of the particles within the channel under various conditions, as is described in the following section entitled “Operation of the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform.”

Operation of the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform

Two permanent magnets were placed into a 3D-printed casing and aligned with either side of the Ni pattern under the PDMS chip. This induced a temporary magnetic field around each of the 50 μm × 50 μm × 200 nm Ni micromagnets patterned inside the microchannel, in order to capture and concentrate SERS-active magnetic nanoparticles. The magnetic polarity of these micromagnets was controlled and was responded along the polarity of two permanent magnets. For instance, the attractive magnetic field of micromagnets can be generated by outer permanent magnet provided attractive filed and vice versa. We introduced three different types of polarity—attractive, repulsive, and random polarity for magnetic trapping platform. A 2 ml volume of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles were introduced into the microchannel inlet at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The focal plane of the confocal Raman microscope was aligned with the surface of the Ni-micropads and adjusted in 10 μm step sizes in order to monitor the XY planar and XZ depth profiles of the SERS signal from the nanoparticles trapped over the micromagnets. All SERS spectra were collected using a ThermoFisher Scientific DXR Raman confocal microscope with a 780 nm laser diode excitation source set at 10 mW. The unit was configured with an 830 lines/mm grating, 50× objective, 50 μm slit aperture, and a thermoelectrically cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera.

Calculation of capture efficiency of magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform

The capture efficiency of the chip was determined by the molar ratio between the remaining magnetic core-shell nanoparticles in the output solution and the stock concentration of magnetic core-shell nanoparticles in the inlet solution as shown in Eq. (1). The stock concentration of magnetic core-shell nanoparticles applied to the inlet was 3 × 109 particles/ml as determined using a Nanosight Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) particle tracking system. The concentration of core-shell nanoparticles in the outlet solution was initially determined by the SERS peak intensity and the area of the aromatic breathing mode at 1075 cm−1,

| (1) |

This result was verified using Beer's law [Eq. 2(a)] and experimental absorbance measurements of the core-shell magnetic particles whose primary absorbance was located at 760 nm. A Varian Cary 300Bio UV-Visible Spectrophotometer with a scan range of 400–1000 nm was used to make the absorbance measurements. Since the particle extinction coefficient and the path length are known to be constant for the inlet and outlet solutions, the equation for finding the outlet concentration derived from Beer's law can be simplified as shown in Eq. 2(b),

SERS MAPPING PROFILE

The distribution profiles and efficiency of particle trapping by this magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform were characterized using the same confocal SERS microscope settings described previously in the chip operation section. SERS spectra were collected using a 10mW laser diode at 780 nm with a total integration time of 10 s (10 sequential scans averaged, each with a 1 s exposure time). The spatial step size used was 10 μm for a total 3D data collection of two Raman scans within a 300 × 150 × 70 μm volume. The red to blue color intensity scale was formed using SERS mapping profiles of the localized particle clusters constructed in OriginPro® software in which the SERS signal intensity of the aromatic breathing mode of the 4-MBA located at 1075 cm−1 was mapped.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Performance of magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform for SERS applications

A bright field image of the five Ni micropads housed within the PDMS channel under 10× magnification is depicted in Fig. 3(a). The images were taken after having captured core-shell magnetic nanoparticles that were pumped into the microchannels at a rate of 5 μl/min. The obvious color change from white to orange was observed on the micropads due the aggregation of iron/silica core and gold shell nanoparticles [Fig. 2(a)] that were captured using the permanent magnet similar to previous observations in the literature by Do et al.25,29 This shows that core-shell magnetic nanoparticles can be guided and localized over each Ni micropad. The SERS mapping profile shown in the second portion of Fig. 3(a) demonstrates that the strongest SERS intensity emanated from within the micropad array regions and was minimal and overcome by the PDMS signal when probing outside of the Ni patterned region. An SEM image of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles trapped over the Ni micropads in the magnetically activated microchannels is depicted in Fig. 3(b). As depicted, the SERS-activated core-shell magnetic nanoparticles were primarily located over the Ni micropads since very few particles were found in the space between each micropad. The SEM images confirm not only that core-shell magnetic nanoparticles can be isolated from solution and are primarily confined to specific areas for automated alignment of the Raman microscope, but also that the SERS signal can be effectively enhanced through magnetic concentration of particles trapped over the Ni micropad area. Figure 3(c) is a comparison among the SERS signal intensities from the blank areas between micropads, the suspended core-shell nanoparticles alone, and when the particles are concentrated on the micropads. The intensity of the SERS signal from the micropads was at least 13-fold higher than the gap area between micropads. Compared to the suspended core-shell magnetic nanoparticle solution, a 10-fold higher enhancement of the SERS signal was detected as a result of magnetic trapping.

FIG. 3.

(a) Brightfield image of micropads aggregating the core-shell magnetic nanoparticles and SERS mapping of the micropads under 10× magnification (scar bar: 50 μm); (b) SEM image of a micropad with magnetically trapped gold coated iron/silica nanoparticles; and (c) comparison of SERS signals of the MBA-functionalized nanoparticle collected from the magnetic micropad area, gap area between pads, and stock solution.

The aggregation of the core-shell magnetic nanoparticles is determined and controlled by the external magnetic polarity. Attractive and repulsive magnetic field and no magnetic field were used as the control. Figure 4 indicates the difference in intensities of the SERS signal among the different magnetic polarities. The highest SERS signal was detected from the micropads with attractive polarity, while the lowest signal was detected from the control group. In this configuration, the Ni material had a slight magnetic response because of the alignment of the dipole in the domain, as the magnetic properties of the Ni micropad were triggered by the external magnetic field polarities. If the orientation of the dipole in each domain was not in the same direction, the magnetic property of each micropad was reduced or even eliminated. As a result, if the orientation is not in the same direction, then the Ni micropad cannot capture core-shell magnetic nanoparticles forming clusters on each micropad nor can it provide the same SERS signal as the dispersed colloidal stock solution.

FIG. 4.

(a) SERS spectra with attractive, repulsive, and no magnetic fields; and (b) depth and width mapping for SERS signal at 1075 cm−1 with attractive, repulsive, and no magnetic fields.

The magnetic polarity of the micropads also influences the particle localization in terms of depth, as characterized by the XZ Raman profile of the channels. The focal plane was set on the surface of the Ni micropads and scanned from the surface of the micropad under static, no flow conditions, to the ceiling of the microchannel with 10 μm resolution. As depicted in Fig. 4(b), the overall scanning distance for the z-direction was 100 μm in each case. Micropads with attractive polarity could create a larger 3-dimensional capturing space in the microchannel than the other polarities, with consistent SERS signals measurable for up to 80 μm in height. The distribution of the SERS signal using attractive polarity was extremely uniform as shown in the bottom of Fig. 4(b). Under repulsive polarity, a small number of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles could still be captured on the micropads. The uniformity is determined by the ratio of standard deviation and mean of the intensity of peak 1075 cm−1.30 The formula is shown below:

The uniformity achieved for attractive polarity was 92%, while the uniformity for repulsive and non-magnetic polarity are 61% and 54%, respectively. The attractive polarity could thus create uniform capture efficiency of magnetic particles on each micropad. Overall, the capture distance in the z-direction, uniformity of particle trapping, and intensity of the SERS signal were much weaker in the case of the control and repulsive fields than as observed with attractive polarity.

Herein, we introduce capture efficiency and trapping efficiency to describe the performance of magnetic trapping platform under different magnetic polarity. Capture efficiency is determined by UV-Vis signals about how many particles can be seized based on the different magnetic polarity, while the trapping efficiency is calculated by SERS signals.

The magnetic particle capture efficiency was quantified under the various external polarities by collecting solutions from the outlet reservoir. UV-Vis spectra and SERS signals were obtained from the outlet samples and the results are shown in Figs. 5(a) and 5(b)–5(d), respectively. Normally, core-shell magnetic nanoparticles have a significant UV-Vis absorbance spectrum at 760 nm, allowing the 780 nm Raman source to fall within the 120 nm window suited for SERS enhancements. However, the UV-Vis spectrum detected from the outlet solution showed a very low intensity broad spectrum around 760 nm. This meant that the output concentration of core-shell nanoparticles using attractive polarity was much lower than the stock solution, which had 3 × 109 particles/ml concentration. Using Beer's law as simplified in Eq. 2(b), it was determined that the chip was able to retain ∼97% of the magnetic nanoparticles using attractive polarity.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of the solution passing through the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform: (a) UV-Vis spectrum of the input and output solutions for the attractive polarity; (b) SERS spectra for core-shell magnetic nanoparticles with different particle concentrations: 3 × 109, 6 × 108, 3 × 107, 1.2 × 107, and 6 × 106 particles/ml; (c) concentration of the standard curve calculated using the data from (b) for core-shell magnetic nanoparticles and a plot of the output solution after magnetic trapping using attractive polarity; and (d) Raman spectra of the output solution for the different polarities: attractive, repulsive, and random (native).

As depicted in Fig. 5(d), the intensity of the SERS peak at 1075 cm−1 from the outlet solution with attractive polarity was fivefold lower than that of the repulsive or random polarities. This result also confirms that the micropads with attractive polarity demonstrated ability to retain the most nanoparticles and produce the highest intensity SERS signals. The concentration of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles collected from output was 2.5 ± 0.49 × 108 particles per milliliter. Thus, the average trapping efficiency as predicted by SERS of the outlet core-shell magnetic nanoparticles with attractive polarity was 91.7 ± 2.8%. This calculated capture efficiency is lower than that predicted using Beer's law likely because some of the non-trapped particles in the outlet aggregate and thus produce a higher SERS signal from the particles in the outlet than would be seen in the absorption measurement. The UV-Vis and SERS results demonstrate that the magnetic trapping platform efficiently captures core-shell magnetic nanoparticles when using attractive polarity. Moreover, the magnetic trapping platform is able to establish “SERS on” or “SERS off” modes by regulating the external magnetic polarity.

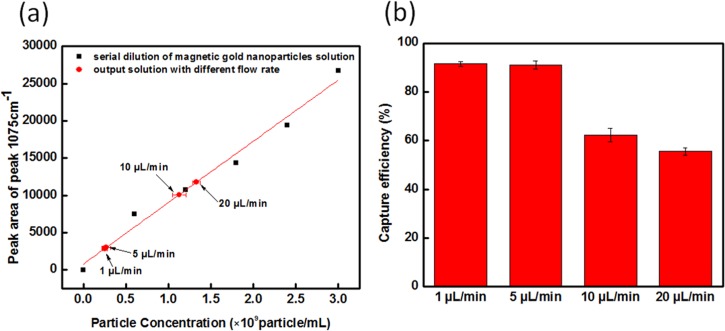

Flow rate was also a crucial parameter for the core-shell nanoparticle trapping efficiency. If the dragging force is higher than magnetic trapping force, core-shell nanoparticles were not trapped. The flow rates evaluated were 20, 10, 5, and 1 μl/min, and the SERS intensity of the output solution was used to predict the trapping efficiency. The slower the flow rate applied to the inlet, the higher the trapping efficiency over the Ni micropads. Figure 6(a) presents the linear relationship between the SERS peak area of the output solution and particle concentration, and the SERS intensity as a function of flow rate applied to the inlet is mapped onto that curve. When the flow rate of fluid was at 20 μl/min, only half of the nanoparticles were trapped on the Ni micropads. Additionally, drag force of the colloid when using 20 μl/min was much higher than the magnetic force provided by the micropads, and therefore the magnetic nanoparticles would pass over the trapping area without being trapped. As the flow rate was reduced from 20 to 5 μl/min, the trapping efficiency improved from 55% to 91%. A reduced flow rate also demonstrated that at this flow rate, the magnetic force overcame the fluidic drag force so that magnetic particles could be trapped over the micropads. The number of particles captured, and hence efficiency results obtained from the flow rate at 5 and 1 μl/min were almost identical, indicating a saturation point. Consequently, it was decided that the maximum trapping efficiency of magnetic core-shell nanoparticles was achieved using a 5 μl/min flow rate within the attractive magnetic field used for these studies.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of the solution passing through the magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform using different flow rates. The flow rate used was 1 μl/min, 5 μl/min, 10 μl/min, and 20 μl/min (a) the peak area for the 1075 cm−1 peak for different flow rates as mapped on the serial dilution calibration curve. (b) trapping efficiency of magnetic micropads under different flow rates.

Time dependent magnetic trapping of the nanoparticles on Ni-micropad array

The core-shell magnetic nanoparticle aggregation behavior over the Ni micropads using the preferred dynamic embodiment of 5 μl/min flow and attractive polarity described previously was investigated further through 2D SERS mapping using a confocal Raman microscope. Figure 7(a) is a schematic diagram of the 2D SERS intensity mapping layers. The SERS detection area can be partitioned into five layers with 10 μm resolution. Figure 7(b) presents the SERS intensity at different points in time and at different depth scanning layers. At time t = 0, it was observed that the highest average SERS signal was located around 40–50 μm above the surface of Ni micropads. Ten minutes later, the SERS signal around the 40–50 μm layer dramatically decreased and the maximum SERS signal shifted to a lower layer, around 20–30 μm above the Ni micropads' surface. Twenty minutes later, more core-shell magnetic nanoparticles were attracted towards the Ni micropads' surface. After 30 min, while still under 5 μl/min flow conditions the distribution of SERS signal approached steady state, and the maximum intensity of SERS signal was located in the region 0–30 μm above the Ni micropads. Based on the distribution of the SERS intensity from the core-shell magnetic nanoparticles as a function of time, the aggregation mechanism of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles for magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform is predicted to be as shown in Fig. 7(c). As time progressed, the maximum intensity of SERS signal was still confined 20–30 μm above the surface of microchannel rather than at the surface micropads because of the continuous flow of nanoparticle solution in the microchannel. Figure 7(d) presents the real mapping of normalized SERS signal as function of time. When the pump is removed and the magnet remains on, after ∼3 to 4 h particles are concentrated even further due to evaporation and the SERS enhancement factor over the magnetic pads is doubled (Fig. 8). After drying, particles may be retained, resuspended, and return to the 20–30 μm confinement reintroduced of solution into to the channel and can be sub-sequentially released from the wells completely when the magnet is removed (Fig. 8). This further demonstrates the chips ability to be used for automatic reagent cycling and time consuming wash steps.

FIG. 7.

(a) Schematic diagram for 2D SERS intensity mapping layers. (b) SERS mapping profiles were collected and the average peak area of the normalized of SERS peak at 1075 cm−1 for one Ni micropad at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 min. (c) Schematic showing the presumptive aggregation of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles on Ni micropads. (d) Depth mapping of normalized SERS signal at 1075 cm−1 at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 min with attractive magnetic fields.

FIG. 8.

Recycling and reuse of magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform. The reuse test is a cyclic process, which consists of three dry-wet cycles. The dry condition is for achieving additional enhancement from magnetic particles on each micropad located in microchannel after water evaporation for static SERS measurements. The wet condition demonstrates trapped magnetic particles concentrated into the 7.5 nl wells over each micropad for dynamic SERS measurement.

CONCLUSIONS

A magneto-fluidic nanoparticle trapping platform was successfully developed for confining core-shell magnetic nanoparticles on lithographically defined Ni micro-pads. The concentration of gold shell–iron core magnetic nanoparticles over the pads was monitored using SERS signals from the Raman reporter 4-MBA, which is dependent on particle distance. The core-shell magnetic nanoparticles were concentrated into a 50 μm × 50 μm × 30 μm (7.5 nl) volume over each of the five Ni micropads. The Ni micropad array exhibited that the trapping mechanism is “on/off” tunable by varying the polarity of the magnetic field. Under attractive polarity, the trapping efficiency of Ni micropad array was four times better than the Ni micropads under repulsive and zero control fields. Additionally SERS enhancements were doubled when particles were dried within the channels, and it was demonstrated that these particles could be dried and resuspended three times, and were able to be released upon removal of the magnet. The fluidic flow rate, varied from 20 to 1 μl/min, was also an essential parameter for the magnetic trapping efficiency, and it was determined that a 5 μl/min flow rate or lower would sufficiently trap the maximum amount magnetic nanoparticles on micropad. The capture efficiency was 97% and the trapping efficiency was 91%.

Using 3D confocal SERS mapping data, the mechanism for determining the location of the core-shell magnetic nanoparticles above the micropads was predicted. It was ascertained that the magnetic nanoparticles aggregated over time by first being gathered above the Ni-micropads toward the center of microchannel due to exposure to initial magnetic fields induced by a permanent magnet which propagates down the patterned Ni micropads. Second, as more magnetic core-shell particles are introduced into the channel over time they are attracted toward the surface of Ni micropads in the presence of the external attractive magnetic field. After 30 min, the SERS intensity was found to reach a steady-state and was consistently distributed starting from the surface of Ni micropad up to a 30 μm area above the five 50 μm × 50 μm Ni micropads housed within the microchannel. This further illustrates that the flow of the fluid effects the particles' packing but, as shown earlier, that the magnetic force is sufficiently strong compared to the dragging force of fluid at 5 μl/min or less to allow trapping and a stable signal at steady state. Based on this mechanism, the magnetic trapping platform presented here can not only generate a 3D nanoparticle sampling volume but also can improve upon microfluidic SERS sensing applications because of the defined depth of a focus (DOF) sensing region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 2R44ES022303–02). H.M. would like to thank Dr. Aaron Saunders at Nanocomposix for his role in the design and synthesis of the Au@SiFe core-shell magnetic nanoparticles.

References

- 1. Huh Y. S., Chung A. J., and Erickson D., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 6, 285–297 (2009). 10.1007/s10404-008-0392-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nie S. and Emory S. R., Science 275, 1102–1106 (1997). 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li M., Cushing S. K., Liang H., Suri S., Ma D., and Wu N., Anal. Chem. 85, 2072–2078 (2013). 10.1021/ac303387a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jackson J. B., Westcott S. L., Hirsch L. R., West J. L., and Halas N. J., Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 257–259 (2003). 10.1103/RevModPhys.57.783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nikoobakht B. and El-Sayed M. A., J. Phys. Chem. A 107, 3372–3378 (2003). 10.1021/jp026770+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mock J. J., Barbic M., Smith D. R., Schultz D. A., and Schultz S., J. Chem. Phys 116, 6755–6759 (2002). 10.1016/0009-2614(74)85388-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tao A. R. and Yang P., J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 15687–15690 (2005). 10.1021/jp053353z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zeman E. J. and Schatz G. C., J. Phys. Chem 91, 634–643 (1987). 10.1021/j100287a028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Etchgoin P. G. and Le Ru E. C., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6079–6089 (2008). 10.1039/b809196j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White I. M., Gohring J., and Fan X., Opt. Express 15, 17433–17442 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.017433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thuy N. T. B., Yokogawa R., Yoshimura Y., Fujimoto K., Koyano M., and Maenosono S., Analyst 135, 595–602 (2010). 10.1039/b919969a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graham D., Thompson D. G., Smith W. E., and Faulds K., Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 548–551 (2008). 10.1038/nnano.2008.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qian X., Zhou X., and Nie S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14934–14935 (2008). 10.1021/ja8062502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hwang H., Han D., Oh Y., Cho Y., Jeong K., and Park J., Lab Chip 11, 2518–2525 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20277d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chrimes A. F., Khashmanesh K., Stoddart P. R., Kayani A. A., Mitchell A., Daima H., Bansal V., and Kalantar-zadeh K., Anal. Chem. 84, 4029–4035 (2012). 10.1021/ac203381n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chou I.-H., Benford M., Beier H. T., Coté G. L., Wang M., Jing N., Kameoka J., and Good T. A., Nano Lett. 8, 1729–1735 (2008). 10.1021/nl0808132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Betancourt T. and Brannon-Peppas L., Int. J. Nanomed. 1, 483–495 (2006). 10.2147/nano.2006.1.4.483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang M., Benford M., Jing N., Coté G., and Kameoka J., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 6, 411–417 (2009). 10.1007/s10404-008-0397-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang M., Jing N., Chou I.-H., Cote G. L., and Kameoka J., Lab Chip 7, 630–632 (2007). 10.1039/b618105h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang H., Harpster M. H., Wilson W. C., and Johnson P. A., Langmuir 28, 4030–4037 (2012). 10.1021/la204890t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marks H. L., Pishko M. V., Jackson G. W., and Cote G. L., Anal. Chem. 86, 11614–11619 (2014). 10.1021/ac502541v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adams J. D. and Tom Soh H., JALA Charlottesv VA 14(6), 331–340 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qian J., Lou X., Zhang Y., Xiao Y., and Soh H. T., Anal. Chem. 81, 5490–5495 (2009). 10.1021/ac900759k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kogot J. M., Zhang Y., Moore S. J., Pagano P., Stratis-Cullum D. N., Chang-Yen D., Turewicz M., Pellegrino P. M., Fusco A. d., Tom Soh H., and Stagliano N. E., PLoS One 6, e26925 (2011). 10.1371/journal.pone.0026925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Do J. and Ahn C. H., “ A polymer lab-on-a-chip for magnetic immunoassay with on-chip sampling and detection capabilities,” Lab Chip 8, 542–549 (2008). 10.1039/b715569g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Whitesides G. M., Ostuni E., Takayama S., Jiang X., and Ingber D. E., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 3, 335 (2001). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ilievski F., Mazzeo A. D., Shepherd R. F., Chen X., and Whitesides G. M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 1890–1895 (2011). 10.1002/anie.201006464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zong S., Wang Z., Yang J., Wang C., Xu S., and Cui Y., Talanta 97, 368–375 (2012). 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Do J., Choi J.-W., and Ahn C. H., IEEE Trans. Magn. 40, 3009–3011 (2004). 10.1109/TMAG.2004.828979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldhamer D. A. and Snyder R. L., Irrigation Scheduling, a Guide for Efficient on-Farm Water Management ( University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1989). [Google Scholar]