Abstract

Infections caused by commensal organisms by changing to infectious life style generate much challenge to the current treatment strategies. Coagulase Negative Staphylococci (CoNS) are one of them, with their coexisting biofilm forming and multiple antibiotic resistance properties form important agents of nosocomial infection. To evaluate species distribution, biofilm formation, and antibiogram, CoNS isolates from various clinical samples were isolated. The presence of biofilm and associated genes icaAB, aap, atlE, embp, bhp, and fbe in CoNS was screened by PCR. The biofilm chemical composition and its correlation with the genotypes were also analysed. Staphylococcus epidermidis (59%) was found to be the most prevalent CoNS species. Most of the CoNS isolates harboring biofilm gene showed carbohydrate-protein-eDNA biofilm, whereas carbohydrate-protein biofilms were also observed. High percentage of multiple drug resistance, and biofilm gene frequency among these CoNS isolates point towards the need of periodic surveillance as CoNS are recently identified to cause difficult to treat infections.

Keywords: Biofilm, Coagulase Negative Staphylococci, Methicillin-resistant CoNS, ica ADBC, ica independent genes, Biofilm heterogeneity

Introduction

Coagulase Negative Staphylococci (CoNS) are commensal bacteria of skin, anterior nares, ear canals, and respiratory and gastrointestinal mucous membranes of humans and animals (Piette and Verschraegen 2009). However, severe life threatening infections caused by CoNS have changed its status from clinically insignificant contaminants to potential pathogens (Prasad et al. 2012). The CoNS can form biofilms on the surfaces of medical devices and it can get introduced into the body through medical procedures involving device insertion. CoNS act as opportunistic pathogens causing nosocomial infections among immunocompromised, immunosuppressed, long-term hospitalized, and critically ill patients (Chu et al. 2008). Among various CoNS, Staphylococcus epidermidis is the major cause of infections associated with catheters, surgical wounds, peritonitis, osteomyelitis, and endophthalmitis (Upadhyayula et al. 2012). Other CoNS members like S. haemolyticus, S. saprophyticus, S. hominis, S. warneri, S. capitis, S. simulans, S. cohnii, S. xylosus, and S. saccharolyticus are also shown to have role as opportunistic pathogens (Mack et al. 2006).

CoNS are known to have the ability to form icaADBC-encoded polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) and ica independent chemically diverse biofilm. Biofilm provide survival advantages to the organism by making the cells less accessible to the defense system of the host and also by impairing the action of antibiotics. The ability to form biofilm is the most important virulence factor of CoNS which facilitate its adherence and colonization on artificial materials. Biofilm formation is a four-step process involving attachment, accumulation, maturation, and detachment. The initial attachment is mediated through various cell wall anchored proteins like Bhp, AtlE, and Fbe as well as intercellular adhesin. The accumulative stage is characterized by the production of icaADBC-encoded polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA). Various reports on PIA independent biofilm formation in CoNS also showed the involvement of two major cell surface associated proteins, namely Aap and Embp. Accumulation-associated protein (Aap) is a member of Bap-like protein family and extracellular matrix-binding protein (Embp) mediate bacterial binding to fibronectin and also participate in biofilm accumulation (Bowden et al. 2005). Recent study on PIA, Aap, and Embp-mediated S. epidermidis biofilms has identified distinct structural features associated with organization of intercellular adhesions. PIA forms an extracellular matrix and thus embeds S. epidermidis cells in a meshwork of fibers resulting in large cell agglomerates. Aap forms tufts of protein fibrils which are strictly localized to the cell surface. Whereas Embp is involved in the adherence of bacterial surfaces and also found in the intercellular space as extracellular proteinaceous matrix. A mature biofilm also incorporates metal ions and macromolecules like proteins, DNA, lipids, and organic substances, to form a three-dimensional and highly ordered structure.

The CoNS are also benefited by the presence of multiple drug resistance as an added advantage. Various Staphylococcal species are considered to have the methicillin resistance acquired through horizontal gene transfer. Since methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS) are usually resistant to other antibiotics, such as beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, and macrolides, it is difficult to treat the infections caused by CoNS (Duran et al. 2012). CoNS have staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCC) mec elements which harbor genes for resistance to methicillin and also for other antibiotics. All these factors necessitate the periodic monitoring of multidrug resistance of CoNS. Although the incidence of infections due to Coagulase Negative Staphylococci is increasing, epidemiological information related to the acquisition and spread of these organisms among population is very limited. Studies on characterization and prevalence of CoNS will help to understand the species distribution and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of human-associated CoNS. This will be very important to develop newer therapeutic strategies for the prevention and effective treatment of CoNS infections. Hence, the current study was conducted to analyse the species distribution and antibiotic resistance properties of CoNS from various clinical samples. In addition, the distribution of biofilm associated genes and the biofilm composition in biofilm forming CoNS was also analysed.

Materials and methods

Collection of samples for the study

A total of 173 isolates from different clinical samples, including exudates, urine, blood, endotracheal catheter tips, and sputum, were collected from a tertiary care hospital in Ernakulam district of Kerala, India. One sample per patient was included in the study.

Biochemical characterization of the isolates

The colonies observed as coagulase negative staphylococci on the basis of colony morphology, gram staining, and tube coagulase test were picked and subcultured on to TSA slants and maintained as pure stock cultures. The isolates were initially identified and characterized as genus Staphylococcus by catalase test. Staphylococcus species was differentiated from Micrococcus on the basis of the acid production from glucose in Hugh and Leifson’s OF base medium, and resistance to bacitracin (8 mcg). All of the suspected CoNS clinical isolates were identified up to the species level using the biochemical tests. The tests used were Mannitol Salt Agar, Urease, Ornithine Decarboxylase, Nitrate Reduction, Phosphatase, and Hemolysis. Acid production from sucrose, trehalose, maltose, lactose, mannose, arabinose and xylose, and susceptibility to novobiocin (5 mcg) (Iorio et al. 2007) were also analyzed.

Antibiotic susceptibility test

Antibiotic sensitivity test of the isolates was conducted on commercially prepared Mueller–Hinton Agar (HiMedia, Mumbai) by disc diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. The antibiotic discs used were ampicillin (25 mcg), chloramphenicol (30 mcg), ciprofloxacin (30 mcg), erythromycin (15 mcg), fusidic acid (30 mcg), gentamycin (10 mcg), levofloxacin (5 mcg), methicillin (5 mcg), penicillin (10 mcg), rifampicin (15 mcg), tetracycline (30 mcg), and vancomycin (15 mcg) (HiMedia, Mumbai). Overnight grown cultures of CoNS were swabbed onto MHA. Using sterile forceps, about five antibiotic discs were placed on the agar surface of each plate. After incubation, zone of inhibition was measured and the interpretation of the results was made in accordance with the chart provided by the manufacturer.

Biofilm assay

All the isolated CoNS were qualitatively analysed for slime formation by culturing on Congo Red Agar (CRA) medium (HiMedia, Mumbai). Inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Quantitative analysis of biofilm production was conducted by measuring bacterial adherence to polystyrene microtitre 96-well plates (Himedia, Mumbai) using crystal violet assay (Oliveira and Cunha 2010). For this, CoNS isolates were cultured overnight at 37 °C in TSB medium (HiMedia, Mumbai). The cultures were diluted to 1:200 using fresh TSB medium and 200 μL of this dilution was transferred to microtitre wells and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the wells were washed four times with 200 μL of sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS), air-dried, and stained with 0.4% crystal violet for 5 min. Then, the plate was rinsed under running tap water and air-dried, and the absorbance was determined at 490 nm after adding 200 μL of 95% ethanol onto each well (Bio-Rad, Microplate reader). The isolates were classified into three categories based on optical density (OD) as non-adherent (OD equal to or lower than 0.111); weakly adherent (OD higher than 0.111 or equal to or lower than 0.222) and strongly adherent (OD higher than 0.222) as per the previously described method (El Farran et al. 2013). The experiment was conducted in triplicates.

PCR detection of biofilm-associated genes in CoNS

Genomic DNA isolation from seventeen strong (S) and twenty four moderate (M) biofilm forming Staphylococcal isolates was carried out using Genomic DNA bacterial minispin kit (Chromous biotech, Banglore). The clinical isolates were screened for icaAB, aap, bhp, atle, fbe, and embp genes which are involved in biofilm formation and attachment to biotic and abiotic surfaces by PCR using Sure Cycler 8800 (Agilent Technologies) (Iorio et al. 2011; Rohde et al. 2004). The amplified PCR products were analysed on 1.5% agarose gel and were visualized using UV trans-illuminator. In addition, the selected PCR products were sequenced to confirm the product identity.

Determination of biochemical heterogeneity of biofilm formed by CoNS

Biofilm producing CoNS isolates were inoculated into 5 mL of TSB medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial cultures were diluted to 1:200 using fresh TSB medium and 200 μL of the dilution was transferred to 96-well tissue culture plates (HiMedia, Mumbai) and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. Mature biofilms formed were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline and were treated with 200 µL of 40 mM NaIO4 (HiMedia, Mumbai), 0.1 mg mL−1 proteinase K (Genei) in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), with 100 mM NaCl, or 0.5 mg mL−1 DNase I (Sigma) in 5 mM MgCl2 for 24 h at 37 °C. Negative control without treatments containing only bacterial cells washed with PBS was also included in the experiment. After incubation, the wells were washed three times with PBS, stained with 0.4% (w/v) crystal violet solution, and measured OD at 490 nm using a Varioskan (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Verdayes et al. 2013). Assays were repeated four times by maintaining the triplicates for test and control and the mean biofilm absorbance values were analysed.

Structural observations of biofilm using HR-TEM

Biofilm formation was confirmed by HR-TEM for strong biofilm forming S. epidermidis (S7) and S. haemolyticus (S9) isolates. From 16 h static incubated cultures, 1 mL aliquots were transferred and the biofilm aggregates were collected by short spinning followed by washing and resuspension in PBS. A thin film of the sample was coated on to carbon coated-copper grid (JEOL-TEM) and was observed for the biofilm production (Archer et al. 2011).

Results

Identification and species diversity analysis of CoNS species

Among 173 clinical samples processed, 152 isolates were identified as CoNS. Based on biochemical tests and novobiocin susceptibility, the CoNS isolates were speciated. In this study, S. epidermidis (59%) was isolated as the predominant CoNS species. The next major group observed was S. haemolyticus with a distribution of 19% and 6% of the clinical CoNS isolates were identified as S. hominis. The CoNS isolates also contained S. saprophyticus (5.2%), S.capitis subsp capitis (5.2%), S. capitis subsp urealyticus (1.3%), S. sciuri (1.3%), and 0.65% of S. cohnii and S. kloosii (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of CoNS isolated from various clinical samples

| CoNS species isolated | Number and percentage of isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exudates (n = 103) |

Blood (n = 24) |

Urine (n = 12) |

Catheter tip (n = 7) |

Sputum (n = 5) |

|

| S. epidermidis | 65 (63%) | 15 (63%) | 2 (17%) | 6 (86%) | 2 (20%) |

| S. haemolyticus | 20 (19%) | 2 (8%) | 6 (50%) | 0 | 1 (40%) |

| S. saprophyticus | 6 (6%) | 1 (4.16%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| S. hominis | 5 (5%) | 3 (12.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. capitis subsps capitis | 5 (5%) | 2 (8.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (20%) |

| S. capitis subsps urealyticus | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. sciuri | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| S. kloosii | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. cohnii | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

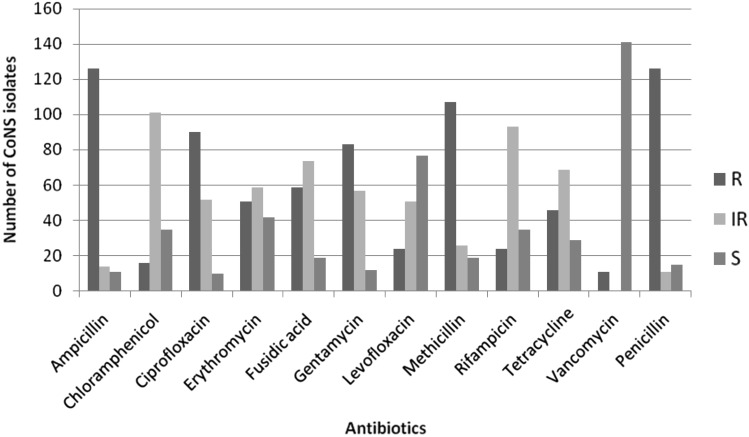

Antibiogram analysis of clinical CoNS isolates showed maximum resistance of 83% towards ampicillin followed by methicillin (70%). None of the isolates were susceptible to all the antibiotics used in this study and 93% of the clinical isolates were found to be susceptible towards vancomycin. Very interestingly, eight S. epidermidis and three S. haemolyticus isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance. The highest percentage of methicillin resistance was shown by S. haemolyticus (97%) followed by S. epidermidis (71%) and S. capitis subsps urealyticus (67%). S. capitis subsps capitis showed 50% methicillin resistance, this was 38% for S. saprophyticus, and 33% methicillin-resistant S. hominis were also detected. The S. sciuri isolated from sputum sample was also found to have methicillin resistance. Except two S. epidermidis isolates, all other vancomycin resistant CoNS isolates were also found to have methicillin resistance. Multiple drug resistances were found to be high for the CoNS isolates (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic sensitivity profile of clinical samples. Where, R, IR, and S indicate number of resistant, intermediate resistant, and sensitive CoNS isolates

Biofilm assay

Congo red agar-based screening for slime production has resulted in the identification of 133 isolates (87.5%) out of 152 CoNS to have this property. Slime-positive isolates formed reddish-black colonies with a rough, dry, and crystalline consistency on CRA, whereas slime negative strains developed pinkish-red, smooth colonies. Quantitative analysis of biofilm formation by microtitre plate assay has identified 11% of the isolates as strong biofilm producers and 16% as moderate biofilm formers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of qualitative and quantitative analysis of biofilm formation by CoNS selected in the study

| CoNS species | Qualitative assay | Quantitative assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRA positive (%) | CRA negative (%) | Strong (%) | Moderate (%) | Weak (%) | |

| S. epidermidis | 91 | 9 | 13.5 | 18 | 68.5 |

| S. haemolyticus | 97 | 3 | 9 | 25 | 66 |

| S. saprophyticus | 80 | 20 | 10 | 40 | 50 |

| S. hominis | 78 | 22 | 0 | 11 | 89 |

| S. capitis subsps capitis | 63 | 37 | 12.5 | 25 | 62.5 |

| S. capitis subsps urealyticus | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

Prevalence of biofilm-associated genes

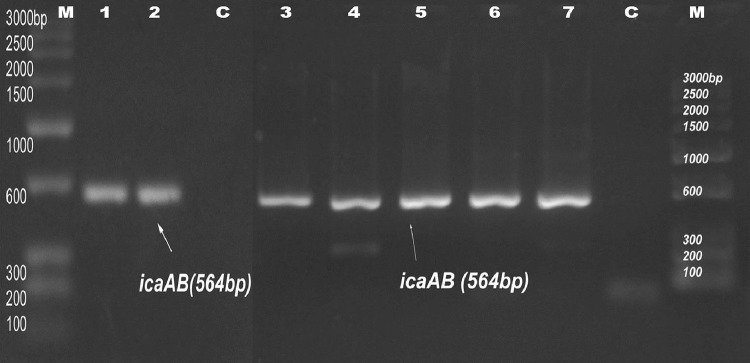

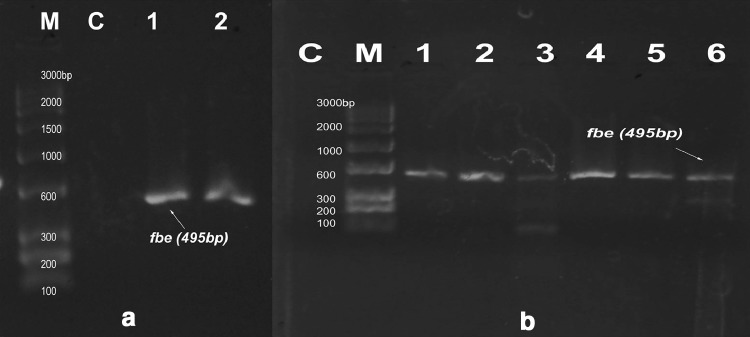

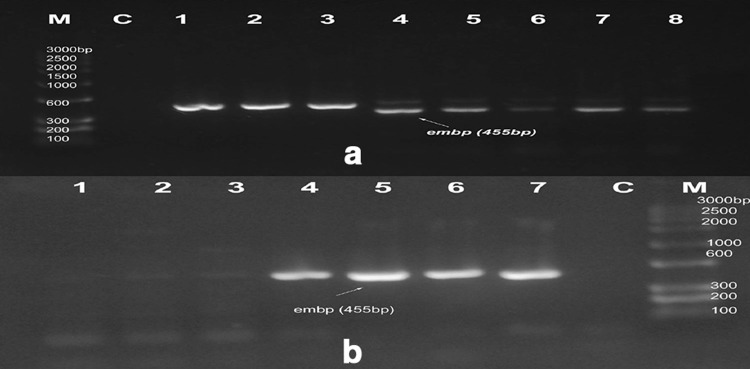

Seventeen strong and twenty-four moderate biofilm forming CoNS were screened for the presence biofilm-associated genes (icaAB, aap, atlE, fbe, bhp, and embp). Among these, nine strong and fourteen moderate biofilm forming isolates were found to have either single or multiple biofilm-associated genes. In detail, two strong biofilm forming S. epidermidis, one S. haemolyticus and moderate biofilm forming isolates of three S. epidermidis, and one S. haemolyticus possessed icaAB gene. In strong biofilm forming CoNS, embp gene was found to have 70% distribution followed by atlE (30%), fbe (20%), and aap (10%). None of the strong biofilm formers was positive for bhp gene. 80% of moderate biofilm forming CoNS possessed aap gene. Moderate biofilm formers also showed high distribution of embp gene (47%) followed by fbe (40%) and atlE (33%). Three strong biofilm formers and seven moderate isolates were found to have more than one biofilm-associated gene. None of the isolate was found to be positive for all the six genes investigated. Three among nine strong CoNS and eight among fourteen moderate CoNS were coupled with multiple biofilm-associated genes. Except in S7 and M5, all other icaAB+ S. epidermidis were found to have the presence of fbe, atlE and embp genes. S. haemolyticus M3 was found to have aap/fbe/atlE/embp genes, M12 with aap/embp, and M4 with embp gene. S. haemolyticus M2, M6, M7 isolates and two S. saprophyticus M1 and M10 isolates contained aap gene only (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7; Table 3).

Fig. 2.

PCR amplification of icaAB at 564 bp. M marker, C negative control. Lanes 1–7 indicate S3, S7, S9, M5, M8, M9, and M10, respectively

Fig. 3.

PCR amplification of fbe gene at 495 bp. M marker, C control. a Lanes 1 and 2 show isolate no: S3 and S8, b Lanes 1–6 indicate M3, M6, M9, M10, M12, and M14

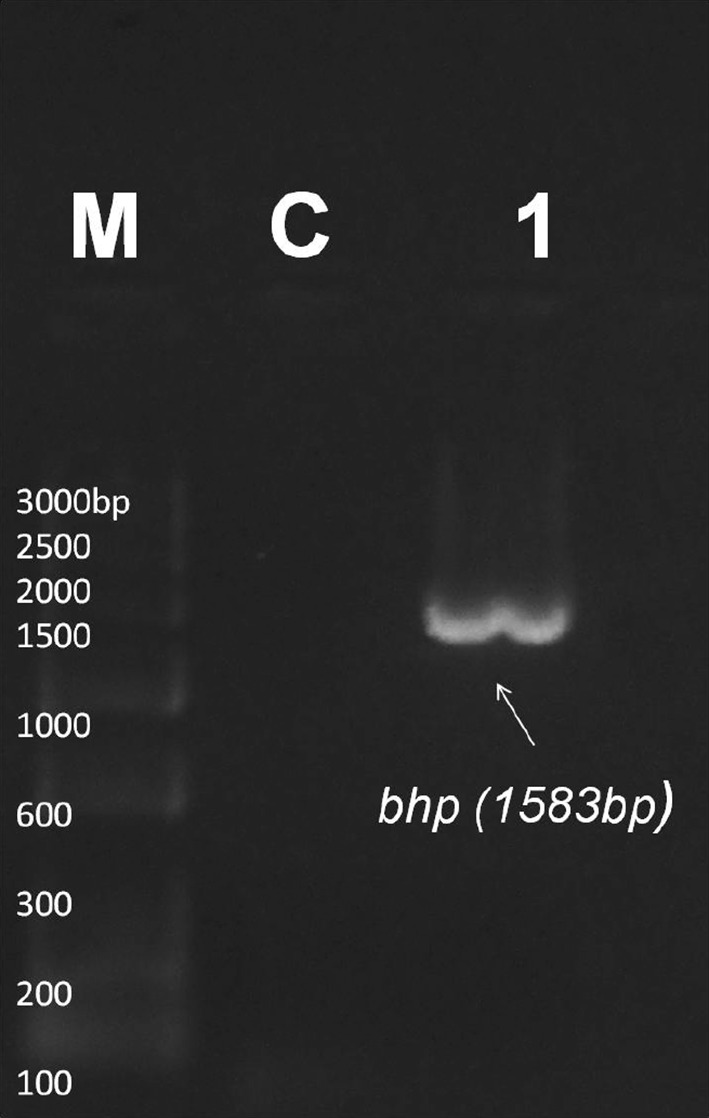

Fig. 4.

PCR for detection of bhp gene at 1583 bp. M marker, C control. Lane 1 indicates bhp positive sample M9

Fig. 5.

PCR amplification of embp genes at 455 bp. M marker, C control. a Lanes no 1–8 show isolates S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7 and S8, b Lanes 1–7 indicate isolates no: M3, M5, M9, M10, M12, M13, and M15, respectively

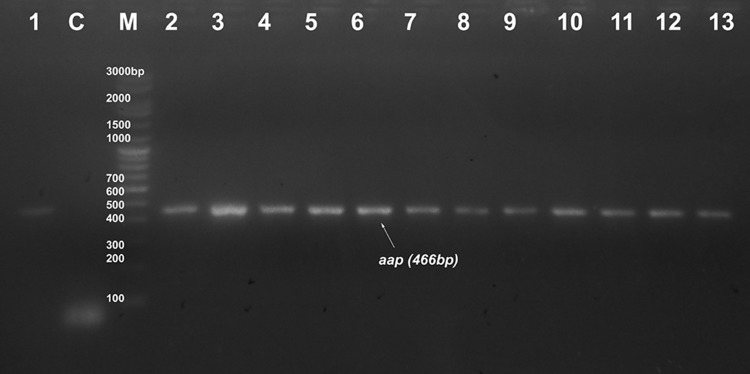

Fig. 6.

PCR result of aap gene at 466 bp. M marker, C control. Lanes 1–13 indicate samples no: S8, M1, M2, M3, M6, M7, M8, M10, M11, M12, M13, M14, and M15, respectively

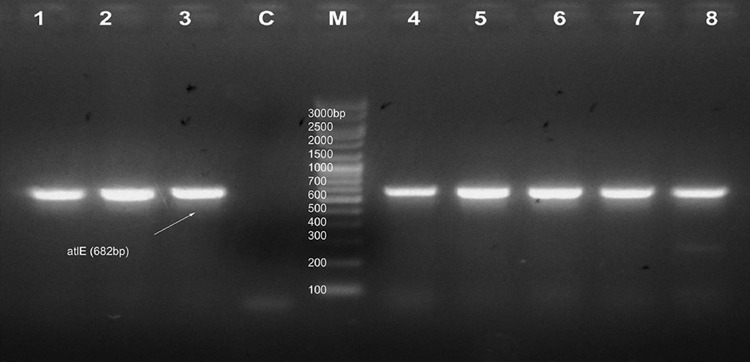

Fig. 7.

PCR results of amplification of atlE gene at 682 bp. M marker, C control. Lanes no 1–8 indicate isolates S3, S7, S8, M3, M6, M9, M10, and M12, respectively

Table 3.

Comparison between genotypes and biofilm composition

| Id | Species | Genes detected by PCR | Biochemical composition of biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S. epidermidis | embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S2 | S. epidermidis | embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S3 | S. epidermidis | icaAB, fbe, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S4 | S. epidermidis | embp | Protein and eDNA |

| S5 | S. epidermidis | embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S6 | S. epidermidis | embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S7 | S. epidermidis | icaAB, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| S8 | S. epidermidis | aap, fbe, atlE, embp | Protein |

| S9 | S. haemolyticus | icaAB | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M1 | S. saprophyticus | aap | Protein and eDNA |

| M2 | S. haemolyticus | aap | Protein |

| M3 | S. haemolyticus | aap, fbe, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M4 | S. haemolyticus | embp | Carbohydrate and protein |

| M5 | S. epidermidis | icaAB, aap, fbe, atlE | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M6 | S. haemolyticus | aap | Protein |

| M7 | S. haemolyticus | aap | Protein |

| M8 | S. epidermidis | icaAB, bhp, fbe, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M9 | S. haemolyticus | icaAB, aap, fbe, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate and protein |

| M10 | S. saprophyticus | aap | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M11 | S. epidermidis | icaAB, aap, fbe, atlE, embp | Carbohydrate, protein, eDNA |

| M12 | S. haemolyticus | aap, embp | Protein |

| M13 | S. epidermidis | aap, fbe | Protein |

| M14 | S. epidermidis | aap, embp | Protein |

S1–S9 indicate strong; M1–M14 indicate moderate biofilm producing CoNS isolates categorized by TCP assay

Association between genotypes and biofilm composition

Multiple biofilm-associated gene harboring S. epidermidis isolates S3 with genotype icaAB/fbe/atlE/embp, S7 with icaAB/atlE/embp, M11 with icaAB/aap/fbe/atlE/embp, and M5 having icaAB/aap/fbe/atlE were identified to have chemically heterogenous biofilm composed of carbohydrates, proteins, and eDNA in accordance with their genotypes. In addition, the bhp gene positive S. epidermidis M8 isolate harboring icaAB/fbe/atlE/embp genes showed susceptibility for all the three treatments used. Biofilm of S. haemolyticus M9 having amplified icaAB/aap/fbe/atlE/embp genes was found to be composed of carbohydrate and protein, whereas S. haemolyticus S9 which contained only icaAB gene showed a diverse carbohydrate-protein-eDNA biofilm. Interestingly, biofilm of some of the isolates which had aap/fbe/atlE/embp and embp gene alone was found to be composed of carbohydrates–proteins-eDNA biofilms which were different from the genotypes identified (Table 3).

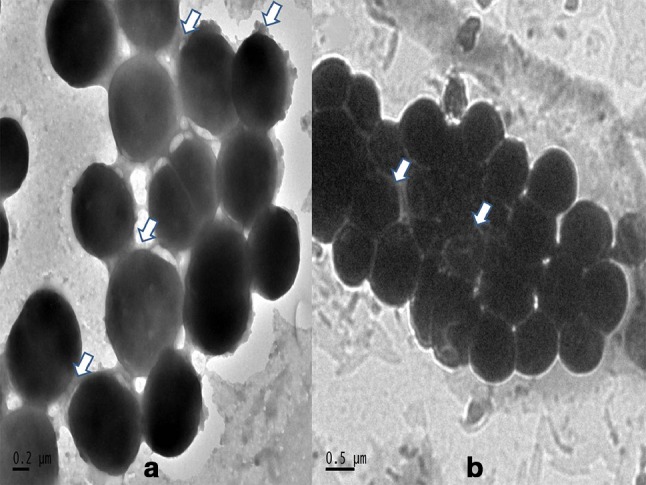

Biofilm formation analysis using HR-TEM

TEM analysis of strong biofilm forming S7 (S. epidermidis, icaAB/embp/atlE) and S9 (S. haemolyticus, icaAB) has been carried out. For both the isolates, amorphous extracellular matrix (ECM) was observed. The agglomerated slime-like structures present on the surface of the bacterial cell and between cells can be indication of presence of PIA. Thick ECM and interconnected localized extended structures from the cell surface were observed in S. epidermidis which may be due to expression of ica independent protein biofilm (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

HR-TEM analysis of biofilm formation of a S. epidermidis and b S. haemolyticus

Discussion

Studies on species diversity, antibiotic resistance, and virulence factors of CoNS are of great significance because of their emerging role as pathogens. As the distribution of various CoNS species in human population can vary, species identification from various clinical samples is very important. In this study, based on the phenotypic identification S. epidermidis was found to be the major CoNS species isolated. Even though S. epidermidis is a ubiquitous member of the normal flora, their emerging role as nosocomial pathogens causing post-operative sepsis, medical implant device related infections in immunocompromised patients, etc. demand studies on its virulence factors and antibiotic resistance (Piette and Verschraegen 2009). Identification of S. epidermidis as major CoNS in the current study proves this. S. haemolyticus (19%) which was identified as the second common species is a well-known clinical CoNS infectious agent. S. haemolyticus is commonly associated with septicemia, wound, bone, and joint infections, and recent reports on its decreased susceptibility to vancomycin and also to other glycopeptide antibiotics generate much concern on the present treatment strategies (Sujatha and Praharaj 2012). S. hominis which usually cause blood stream infections is also known to have their presence in clinical samples in the similar frequency as obtained in the study (Goyal et al. 2006). S. saprophyticus are commonly associated with urinary tract infection in humans and these are usually isolated as second common CoNS from clinical samples, but, in this study, their distribution was only 5.2%. The prevalence of different CoNS species can vary with the clinical sample. In the current study samples from exudates had a prevalence of S. epidermidis 63% followed by S. haemolyticus 19%, whereas, for blood samples, 63% S. epidermidis and 8% S. haemolyticus were present. Urine samples had highest isolation frequency for S. haemolyticus (50%).

CoNS strains with multiple resistance to antibiotics are becoming a big problem in nosocomial infections. Among 152 isolates studied, 126 were resistant to ampicillin. In the current study, 70% of the isolates were found to have resistance towards methicillin. Nosocomial isolates generally have up to 80% resistance to methicillin, and moreover, it is also associated with multidrug resistance. Consistent usage of vancomycin in hospitals has a risk of emergence of resistant strains (Schwalbe et al. 1987). Since vancomycin is the drug of choice for the treatment of various CoNS infections, 7% vancomycin resistant isolates observed in the current study are very significant. This indicates the difficulty in use of vancomycin for the treatment and also the potential to disseminate this resistance factors to other bacteria. Moreover, ten isolates were found to have resistance for both vancomycin and methicillin on disc diffusion assay, which indicate the evolution of potential multidrug resistant CoNS among the clinical isolates studied. As vancomycin resistance is spreading all over the world, these observations are very important. Even though multidrug combinational therapy using rifampicin–vancomycin and rifampicin–fusidic acid can be effective against vancomycin resistant strains, evolution of resistance mechanisms in CoNS is to be periodically analysed.

Recent studies show the presence of very remarkable and diverse attachment factors and biofilm forming mechanisms in CoNS. This facilitates the colonization and survival of CoNS on the surface of medical devices in vivo after the device insertion. The 87% frequency of slime production identified in this study is comparable to the previous report of 83% of slime production in CoNS isolated from catheter-associated infections (Cafiso et al. 2004). However, by the quantitative analysis on biofilm production, only 11% of CoNS were identified to be strongly positive. Very interestingly, 96% of the methicillin-resistant strains isolated in this study were also found to be positive for slime production and such an association has already been suggested (Mack et al. 2002).

Of the 17 strong and 24 moderate biofilm forming CoNS screened genotypically, only nine strong and fourteen moderate CoNS were found to be positive for either single or multiple biofilm genes. When cultivated in TSB, majority of CoNS showed the expected relationship between their genotypes and biofilm compositions. Rest of the isolates can be expected to have more diverse type of biofilm. The existence of carbohydrate, protein, and eDNA biofilms or their combinations has previously been described in many studies (Fredheim et al. 2009; Verdayes et al. 2013). In addition, multifunctional proteins in Staphylococci were found to make the biofilm more diverse. In another study, biofilm heterogeneity and its relationship to genotypes were detailed using the CLSM analysis (Schommer et al. 2011). The existence of undetermined biofilm due to altered or modified product of proteins and carbohydrates with organic and inorganic substituents or even formed of other biomolecules has also been suggested (Verdayes et al. 2013). Genes involved in biofilm production have been suggested as major virulence determinants relevant for clinically significant CoNS strains. In addition, different studies have reported the significant association of ica locus and mecA with infecting strains of S. epidermidis than the contaminating strains (Frebourg et al. 2000). In a previous study on CoNS from similar clinical sources, comparable CoNS species distribution was found. This study also demonstrated the presence of potential virulence factors like capsule, slime, biofilm, esterase, siderophore, DNase, multiple antibiotic resistance, and biofilm-associated genes in CoNS (Suja et al. 2011).

Epidemiological studies of ica operon in S. epidermidis from biofilm-associated catheter and prosthetic joint infections showed it to have a distribution of 33–52%. However, other evidences suggest the existence of in vivo expression of PIA independent mechanisms resulting in complex biofilm architecture (Schommer et al. 2011). Our investigation showed a higher percentage of attachment factors and proteinaceous biofilm factors in CoNS, especially in S. epidermidis. These indicate that biofilms are formed through the parallel expression of diverse mechanisms. It was found that 17% of the TCP assay positive isolates contained icaAB genes and multiple biofilm genes were also common among these isolates. A similar result for ica operon was reported for clinical strains of S. epidermidis (Qin et al. 2007). Co-existence of ica independent genes with icaADBC operon has also been found to be frequent in S. epidermidis. Since S. haemolyticus reported to have the highest level of antibiotic resistance among the CoNS, assistance of multiple biofilm genes among them found to be rather alarming. Reports on PIA forming S. saprophyticus exist, whereas this study also exposed the possibility of harboring ica independent genes among these CoNS species. In addition, some of the genotypes of CoNS tested showed variation in their biofilm composition. On TEM analysis of two isolates harboring icaAB gene, they showed ECM formation. In S. epidermidis, thick slime-like layer was observed. Rod-like structures emerging from cell wall interconnecting to other bacterial cells were also seen and this may be due to proteinaceous factors (Takahashi et al. 2015).

Coagulase Negative Staphylococci are emerging multidrug resistant pathogens, and hence, studies on their local species distribution, antibiotic sensitivity, and prevalence of biofilm-associated genes are very important. The CoNS isolates of current study showed multiple antibiotic resistance similar to the other global reports. Co-existence of multiple antibiotic resistance and biofilm genes among many isolates can result in untreatable conditions. Studies on the prevalence of ica dependent and ica independent biofilm genes and biofilm chemical heterogeneity help to understand their role and interaction with each other and are necessary to identify new targets to develop therapeutic approaches. Further studies are needed to define the roles of the different components of undetermined biofilms and their regulation. Resistance to vancomycin shown by some of the members can have serious impact because of the possibility to spread this to other bacterial strains. Thus, proper strategies should be adopted for the control and prevention of infections and this requires close monitoring and periodic inspections of these potential multidrug resistant nosocomial pathogens.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research, Government of India. We express sincere thanks to the Dean and laboratory staffs of MOSC Medical College, Kolenchery, Kerala. We also thank DBT-MSUB for providing instrumentation facility.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Archer NK, Mazaitis MJ, Costerton JW, et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation, and roles in human disease. Virulence. 2011;2:445–459. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.17724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GM, Chen W, Singvall J, et al. Identification and preliminary characterization of cell-wall-anchored proteins of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiol. 2005;151:1453–1464. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafiso V, Bertuccio T, Santagati M, et al. Presence of the ica operon in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis and its role in biofilm production. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:1081–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu VH, Woods CW, Miro JM, et al. Emergence of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci as a cause of native valve endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:232–242. doi: 10.1086/524666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran N, Ozer B, Duran GG, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes & susceptibility patterns in staphylococci. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:389–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Farran CA, Sekar A, Balakrishnan A, et al. Prevalence of biofilm-producing Staphylococcus epidermidis in the healthy skin of individuals in Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31(1):19. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.108712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frebourg NB, Lefebvre S, Baert S, et al. PCR-based assay for discrimination between invasive and contaminating Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. J Bacteriol. 2000;38:877–880. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.877-880.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredheim AGE, Klingenberg C, Rohde H, et al. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus haemolyticus. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1172–1180. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01891-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Singh NP, Kumar A, et al. Simple and economical method for speciation and resistotyping of clinically significant coagulase negative staphylococci. Ind J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:201–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio NLP, Ferreira RBR, Schuenck RP, et al. Simplified and reliable scheme for species level identification of Staphylococcus clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2564–2569. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00679-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio LP, Azevedo B, Frazao H, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis carrying biofilm formation genes: detection of clinical isolates by multiplex PCR. Int Microbiol. 2011;14:13–17. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D, Sabottke A, Dobinsky S, et al. Differential expression of methicillin resistance by different biofilm-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis transposon mutant classes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:178–183. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.178-183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D, Rohde H, Harris LG, et al. Biofilm formation in medical device-related infection. Int J Artif Organs. 2006;29:343–359. doi: 10.1177/039139880602900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira A, Cunha RS. Comparison of methods for the detection of biofilm production in coagulase-negative staphylococci. BMC Res Notes. 2010;260:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette A, Verschraegen G. Role of coagulase-negative staphylococci in human disease. Vet Microbiol. 2009;134:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Nayak N, Satpathy G, et al. Molecular & phenotypic characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis in implant related infections. Ind J Med Res. 2012;136:483–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Yang X, Yang L, et al. Formation and properties of in vitro biofilms of ica-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:83–93. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde H, Kalitzky M, Kroger N, et al. Detection of virulence-associated genes not useful for discriminating between invasive and commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from a bone marrow transplant unit. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5614–5619. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5614-5619.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schommer NN, Christner M, Hentschke M, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis uses distinct mechanisms of biofilm formation to interfere with phagocytosis and activation of mouse macrophage-like cells 774A.1. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2267–2276. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01142-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe RS, Stapleton JT, Gilligan PH. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in coagulase negative staphylococci. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:927–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suja P, Minu T, Radhakrishnan EK, Jyothis M. Species distribution and virulence properties of coagulase negative staphylococci isolated from human and domestic animal sources. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2011;3:743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha S, Praharaj I. Glycopeptide resistance in gram-positive cocci. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/781679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi C, Kalita G, Ogawa N, et al. Electron microscopy of Staphylococcus epidermidis fibril and biofilm formation using image-enhancing ionic liquid. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407:1607–1613. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyayula S, Mamatha K, Asmar BI. Staphylococcus epidermidis urinary tract infection in an infant. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:1–2. doi: 10.1155/2012/983153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdayes AM, Perez LM, Paez AL, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis with the icaA−/icaD−/IS256− genotype and protein or protein/extracellular-DNA biofilm is frequent in ocular infections. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1579–1587. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.055210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]