Abstract

In soil, plant roots coexist with bacteria and fungi that produce siderophores capable of sequestering the available iron. Microbial cyanogenesis has been demonstrated in many species of fungi and in a few species of bacteria (e.g., Chromobacterium and Pseudomonas). Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates P29, P59, P144, P166, P174, P187, P191 and P192 were cyanogenic and produced siderophores in the presence of a strong chelater 8-Hydroxyquinoline (50 mg/l). A simple confrontation assay for identifying potential antagonists was developed. Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates P66, P141, P144, P166 and P174 were antagonistic against both Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii. Vigorous plant growth was observed following seed bacterization with P141, P200 and P240. In field experiments, seed bacterization with selected bacterial isolates resulted in reduced collar rot (S. rolfsii) incidence.

Keywords: Fluorescent Pseudomonads, Collar rot, HCN, Siderophores, Confrontation assays

Introduction

Rhizosphere inhabiting fluorescent Pseudomands are one of the most dominant and potentially most promising group of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria involved in the bio-control of plant diseases (Haas and Défago 2005; Glick 2014). They maintain soil health by employing a wide variety of mechanisms, including nitrogen fixation, enhanced solubilization of phosphate and phytohormone production that positively impact plant health (such as auxins and cytokinins) (Penrose and Glick 2003; Mirza et al. 2006). Pseudomonas spp. produce an arsenal of antimicrobials (including hydrogen cyanide (HCN), pyoluteorin, phenazines, pyrrolnitrin, siderophores, cyclic lipopeptides and 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) (Thomashow and Weller 1996; Weller 2007). They also are able to promote plant growth and induce systemic resistance (ISR) in plants (Raaijmakers et al. 2009; Glick 2014). In the present study we evaluate fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates for siderophore (CAS assay-plate screening, CAS assay-spectrophotometric analysis, hydroxyquinoline test, tetrazolium test, FeCl3 test and Arnow’s assay) and HCN production. Pseudomonas spp. have been employed efficiently as commercial biocontrol agents (Loper and Lindow 1987; Walsh et al. 2001). However, there is always a scope for isolating better, locally adapted strains for deployment as biocontrol agents. Hence, we have screened local isolates of fluorescent Pseudomonads for developing formulation and possible commercialization for the management of collar rot of chickpea (S. rolfsii Sacc), one of the major biotic factors contributing towards low production (55–95% mortality of chickpea seedlings).

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

The experimental material consisted of purified 29 isolates of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. from soils (rhizospheric and non-rhizospheric) of different geographical locations of Chhattisgarh. Isolation of fluorescent pseudomonads was done by adopting serial dilution method on King’s B (KB) medium. After incubation at 28 °C for 2 days, fluorescent pseudomonad colonies from plates were identified under UV light (366 nm). Isolates were characterized on the basis of biochemical tests as per the procedures outlined in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Sneath et al. 1986). Isolated colonies of fluorescent Pseudomonas were further streaked onto KB agar plates to obtain pure cultures. The isolates were maintained (at −80 °C on King’s B broth (Himedia) containing 30% (v/v) glycerol) in the culture collections of the Department of Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Indira Gandhi Krishi Vishwavidyalaya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India, and revived on King’s B slants when required.

Siderophore production

Siderophore production (qualitative and quantitative) was determined by (CAS assay (Schwyn and Neilands 1987). Specific tests were carried out for identification of hydroxamate and Catecholate types of siderophores following the standard methods (Arnow 1937). Chrome azurol S solution was prepared and added to melted King’s B agar medium in the ratio 1:15. Spot inoculation at the centre of the CAS plate was done from actively growing cultures of Pseudomonas. Colonies exhibiting an orange halo after 3 days of incubation (28 ± 2 °C) were considered positive for siderophore production and the diameter of the orange halo was measured.

Hydroxyquinoline mediated siderophore test

For selection of Pseudomonas isolates with high ability to siderophores, isolates were inoculated on King’s B medium supplemented with a strong chelater 8-Hydroxyquinoline (50 mg/l) (De Brito et al. 1995). Inoculated isolates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 48–72 h; only those bacteria that produce a more avid iron chelator will grow.

Arnow’s assay

Arnow’s assay was used for quantification of catechol type siderophore. For qualitative estimation of siderophores, actively growing cultures of Pseudomonas were inoculated to 20 ml King’s B medium in 50 ml tubes and incubated for 3 days at 28 ± 2 °C. The bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Three ml of the culture supernatant was then mixed with 0.3 ml of 5 N HCl solution, 1.5 ml of Arnow’s reagent (10 g NaNO2, 10 g Na2MoO4·2H2O dissolved in 50 ml distilled water) and 0.3 ml of 10 N NaOH. After 10 min the presence or absence of pink colour was observed and noted.

Tetrazolium test

This test is based on the capacity of hydroxamic acid to reduce tetrazolium salt by hydrolysis of hydroxymate groups using a strong alkali. The reduction and release of alkali shows red colour to a pinch of tetrazolium salt when 1–2 drops of 2 N NaOH and 0.1 ml of test sample are added. Instant appearance of a deep red colour indicated the presence of hydroxamate siderophore.

FeCl3 test

One ml of the culture supernatant was mixed with freshly prepared 0.5 ml of 2% aqueous FeCl3 and observed for the presence and absence of deep red colour.

HCN production

The production of HCN was estimated by the method of Wei et al. (1991). The cultures were grown on KM plates supplemented with 4.4 g/l glycine as a precursor and the filter paper strips soaked in saturated picric acid solution were exposed to the growing Pseudomonas isolates. The plates were incubated for 7 days at 28 ± 2 °C and observations were recorded as change in the colour of filter paper to brown as positive indicator for HCN production.

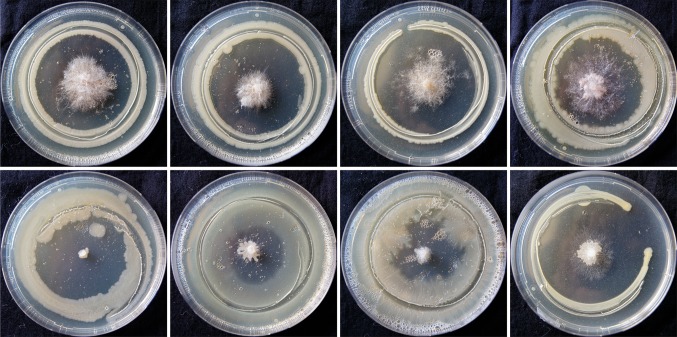

Confrontation assay

Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates were multiplied on King’s B broth and incubated for 2 days at 28 °C till the fluorescent pigment appeared in the broth. Petri-plates containing pre-sterilized potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium were inoculated with plant pathogenic fungi Sclerotium rolfsii or Rhizoctonia solani (in the centre) and incubated at 252 °C for 3 days till the fungus completely covered the entire plate. Bipartite interactions were performed following a simple confrontation assay which was developed during the course of investigation. To identify prospective bio-agent, a simple confrontation assay was developed wherein edge of glass funnel was deployed for bio-agent inoculum deposition surrounding pre-inoculated fungal pathogen. The edge of a glass funnel was sterilized by dipping in alcohol followed by flaming. Broth containing young growing cell (3-day-old) of fluorescent Pseudomonas was dispensed in sterile petri dish and picked at the edge of the funnel by dipping. Care was taken to remove the excess inoculum by gently shaking the funnel. Inoculation was done by gently touching the edge of the funnel (containing fluorescent Pseudomonas) which encircled the pre-inoculated plant pathogenic fungi on agar plug equidistantly (Fig. 1). Inhibition zone was measured after 72 h of incubation at 28 ± 2 °C. Percent inhibition of pathogens by Pseudomonas isolates over control was calculated using the formula of (Vincent 1947): [(Growth of pathogen in control − growth of pathogen with Pseudomonas isolate)/growth of pathogen in control] × 100. Proposed technique has the following advantages: (1) uniform inoculum deposition during all combinations of bipartite interactions. (2) Replica-plating can be done of the inoculum picked on the edge of the funnel. (3) Ability to evaluate the antagonistic potential of a sporulating bio-inoculant (e.g. Trichoderma sp.). The only disadvantage with this technique is that for each bio-inoculant in the broth a separate plate is required to dispense the inoculums.

Fig. 1.

Confrontation assay

Field trial for testing selected fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against chickpea collar rot

For field trials seed bacterization was done with stock cultures (used for confrontation assays) of selected fluorescent Pseudomonas isolate. Slurry for seed bacterization was prepared @ 5 ml of bacterial culture + 3 g of talcum powder/kg of chickpea seeds. Care was taken for uniform coating of all the seeds, which were dried in shade and then sown in a field naturally infested with S. rolfsii. Sowing was done in 2 M × 7 M plots. Care was taken to carry out all normal agricultural practices. Observations were recorded on germination, plant vigour, mortality and bundle and grain weight.

Results

Qualitative and quantitative assay for siderophore production

In the present investigation, 29 isolates of Pseudomonas were screened by six different siderophore assays viz., CAS assay-plate screening, CAS assay-spectrophotometric analysis, hydroxyquinoline test, tetrazolium test, FeCl3 test and Arnow’s assay. All isolates exhibited an orange halo after 3 days of incubation (28 ± 2 °C) on CAS agar plate and, therefore, were considered positive for siderophore production. Intensity of orange halo and diameter showed wide variation among the isolates, which ranged from 11.50 (isolate P56) to 64.50 (isolate P191) mm. Isolates P29, P59, P66, P141, P144, P166, P174, P187, P191, P192, P200, P207 P229 and P260 were identified as producer of more avid iron chelator as they were tested +ve in King’s B medium supplemented with a strong chelater 8-Hydroxyquinoline (50 mg/l). Three isolates (P7, P43 and P45) tested positive in Arnow’s assay (detects catechol type of siderophores). We observed that isolates P43 and P45 tested −ve in HQ test but were +ve for other siderophore tests. All isolates produced deep red colour on addition of tetrazolium salt and NaOH indicating the production of hydroxamate type of siderophores (reduce tetrazolium salt by hydrolysis of hydroxamate group in presence of strong alkali). FeCl3 test was positive for isolates P7, P23, P29, P43, P59, P66 P74, P80, P123, P141, P144, P174, P180, P187, P192, P200, P207 and P260. Only one isolate (P7) tested positive for all siderophore tests. Carboxylate type of siderophore was determined by spectrophotometric method at 630 nm and the percentage of siderophore unit ranged from 12.23 (isolate P130) to 70.60% (isolate P43) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quantitative and qualitative and estimation of siderophores by different tests, HCN production and antagonistic activity of fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii

| Isolates | Quantitative % siderophore units | Qualitative siderophore test | HCN production | % inhibition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS | Arnow’s | FeCl3 | Tetrazolium | HQ | R. solani | S. rolfsii | |||

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates with high ACC deaminase activity (data not shown) | |||||||||

| P66 | 78.555 ± 0.39a | 63.5 ± 1.5a | +ve | +ve | +++ | – | 68.89 ± 1.11a | 82.78 ± 2.78b | |

| P141 | 80.15 ± 0.15a | 55 ± 1b | +ve | +ve | + | – | 52.78 ± 2.78c | 43.335 ± 2.22g | |

| P200 | 49.475 ± 2.11f | 45.5 ± 1.5de | +ve | +ve | + | – | 60 ± 5.56b | 28.89 ± 1.11i | |

| P229 | 22.365 ± 1.32l | 36 ± 1h | + | – | 19.445 ± 2.78j | 28.885 ± 4.45i | |||

| P260 | 71.05 ± 2.63b | 61.5 ± 0.5a | +ve | +ve | ++ | – | 37.775 ± 5.56gh | 32.775 ± 3.33hi | |

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates ineffective against R solani and S. rolfsii | |||||||||

| P2 | 37.25 ± 1.06i | 35 ± 1h | +ve | + | – | 40.5 ± 0.5fg | 17.25 ± 0.55j | ||

| P3 | 30.2 ± 0.28j | 52.5 ± 2.5bc | +ve | + | – | 32.95 ± 0.45hi | 17.1 ± 0.4j | ||

| P43 | 70.6 ± 0.85b | 41 ± 1efg | +ve | +ve | +ve | – | – | 26.2 ± 1.2ij | 33.95 ± 0.65hi |

| P45 | 24.15 ± 0.21l | 16.5 ± 1.5i | +ve | +ve | – | + | 13.05 ± 0.55kl | 25.1 ± 0.7i | |

| P130 | 47.5 ± 0.32f | 31.5 ± 1.5hi | +ve | + | – | 25.15 ± 0.15ij | 31.85 ± 0.75hi | ||

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates moderately effective against R solani and S. rolfsii | |||||||||

| P163 | 47.5 ± 0.71f | 40 ± 2fgh | +ve | – | – | 21.825 ± 0.58j | 45.15 ± 0.75g | ||

| P123 | 43.78 ± 0.31g | 39 ± 2gh | +ve | +ve | ++ | – | 33.15 ± 0.65hi | 34 ± 0.7h | |

| P150 | 43.78 ± 0.31g | 42.5 ± 2.5efg | +ve | + | + | 38.2 ± 0.7gh | 44.95 ± 0.55g | ||

| P23 | 48.25 ± 0.35f | 42 ± 2efg | +ve | +ve | – | – | 39.375 ± 0.63fg | 45.05 ± 0.65g | |

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates effective against S. rolfsii (non HCN producing) | |||||||||

| P56 | 27.5 ± 0.71k | 11.5 ± 1.5i | +ve | – | – | 10.8 ± 0.8l | 50.65 ± 0.65f | ||

| P184 | 40.615 ± 0.87h | 40.5 ± 0.5fgh | +ve | +ve | – | – | 18 ± 0.5jk | 50.75 ± 0.75f | |

| P207 | 36.16 ± 0.23i | 51 ± 1bc | +ve | +ve | +++ | – | 46.875 ± 0.63de | 72.8 ± 0.6c | |

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates effective against S. rolfsii (HCN producing) | |||||||||

| P132 | 23.835 ± 0.23l | 41 ± 1efg | +ve | + | + | 13.15 ± 0.65kl | 61.95 ± 0.85d | ||

| P7 | 52.9 ± 0.14e | 41.5 ± 1.5efg | +ve | +ve | +ve | ++ | + | 21.625 ± 0.38j | 61.8 ± 0.7d |

| P192 | 36.115 ± 0.16i | 54.5 ± 1.5b | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 28.2 ± 0.7i | 56.25 ± 0.65e | |

| P191 | 47.945 ± 0.08f | 64.5 ± 1.5a | +ve | +++ | + | 30.8 ± 0.8i | 72.6 ± 0.4c | ||

| P59 | 60.5 ± 0.71c | 39.5 ± 1.5gh | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 36.625 ± 0.38gh | 47.3 ± 0.6fg | |

| P29 | 60.5 ± 0.71c | 54.5 ± 1.5b | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 43.85 ± 1.35ef | 87.3 ± 0.6a | |

| P187 | 60.115 ± 0.16c | 51.5 ± 1.5bc | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 44.325 ± 0.57ef | 74.05 ± 0.75c | |

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates effective against R solani (non HCN producing) | |||||||||

| P74 | 27.75 ± 0.35k | 40.5 ± 2.5fgh | +ve | +ve | + | – | 50.7 ± 0.7cd | 35.4 ± 0.3h | |

| P80 | 32.5 ± 0.71j | s ± 1.5def | +ve | +ve | ++ | – | 63.1 ± 0.6b | 63.85 ± 0.55d | |

| Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates effective against R solani and S. rolfsii (HCN producing) | |||||||||

| P144 | 43.5 ± 0.71g | 48.5 ± 1.5cd | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 50.7 ± 0.7cd | 76 ± 0.4c | |

| P166 | 60.115 ± 0.16c | 40 ± 3fgh | +ve | +++ | + | 73.1 ± 0.6a | 73 ± 0.8c | ||

| P174 | 55.5 ± 0.71d | 51 ± 1bc | +ve | +ve | +++ | + | 51 ± 1cd | 82.95 ± 0.75b | |

| Max. | 80.15 | 64.5 | 73.1 | 87.3 | |||||

| Min. | 22.365 | 11.5 | 10.8 | 17.1 | |||||

| CV | 2.352 | 5.22 | 6.625 | 3.645 | |||||

| CD (0.01) | 2.962 | 6.33 | 6.876 | 5.12 | |||||

| CD (0.05) | 2.198 | 4.697 | 5.102 | 3.799 | |||||

| F cal | 527.375** | 53.39** | 90.948** | 247.998** | |||||

Values are average of three replications; values after ± represent standard deviation

As per Duncan’s grouping means with the same letter are not significantly different

CV coefficient of variance, CD critical difference, HQ hydroxyquinoline test

+++ Luxuriant/high growth

++ Medium growth

+ Low growth

– No growth

** Values are significant at 1 and 5% levels

Screening for hydrogen cyanide production

To identify cynogenic fluorescent Pseudomonas, isolates were inoculated on KMB plates supplemented with 4.4 g/l glycine (precursor molecule of HCN) and incubated for 7 days at 28 ± 2 °C. Development of brown colour on filter paper strips soaked in saturated picric acid solution indicated +ve for HCN production. Out of the 29 fluorescent Pseudomonas tested, 12 isolates (P7, P29, P45, P59, P132, P144, P150, P166, P174, P187, P191 and P192) tested positive for HCN producing ability. We observed a correlation between inhibitory effects observed following confrontation assays and the ability to produce HCN by fluorescent Pseudomonas. Cynogenic (HCN producers) isolates P132, P7, P192, P191, P59, P29, P187 exerted strong antagonism against S. rolfsii, where as a non-cynogenic isolate P74 exerted strong inhibitory effects against R. solani. On the contrary, a noncynogenic (P80) and three cyanogenic (P144, P166, P174) fluorescent Pseudomonas exerted strong inhibitory effects against both the soilborne fungal pathogens R. solani and S. rolfsii (Table 1).

In vitro antagonistic activity of Pseudomonas isolates against R. solani and S. rolfsii

There were differences in the antagonistic abilities of fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against both (R. solani and S. rolfsii) pathogens (Fig. 1; Table 1). All of the 29 isolates of fluorescent Pseudomonas showed different degree of growth inhibitions of R. solani and S. rolfsii, ranging from 10.8 to 73.1% and 17.1 to 87.3%, respectively. Confrontation assays revealed P166 and P29 as potential antagonists against R. solani and S. rolfsii, respectively, while isolates P56 and P3 were ineffective. Fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates P29, P187, P191, P192 and P207 exerted strong inhibitory effects on the mycelia growth of S rolfsii whereas isolates P66, P141, P144, P 166 and P174 expressed strong inhibitory effects on both R. solani and S. rolfsii.

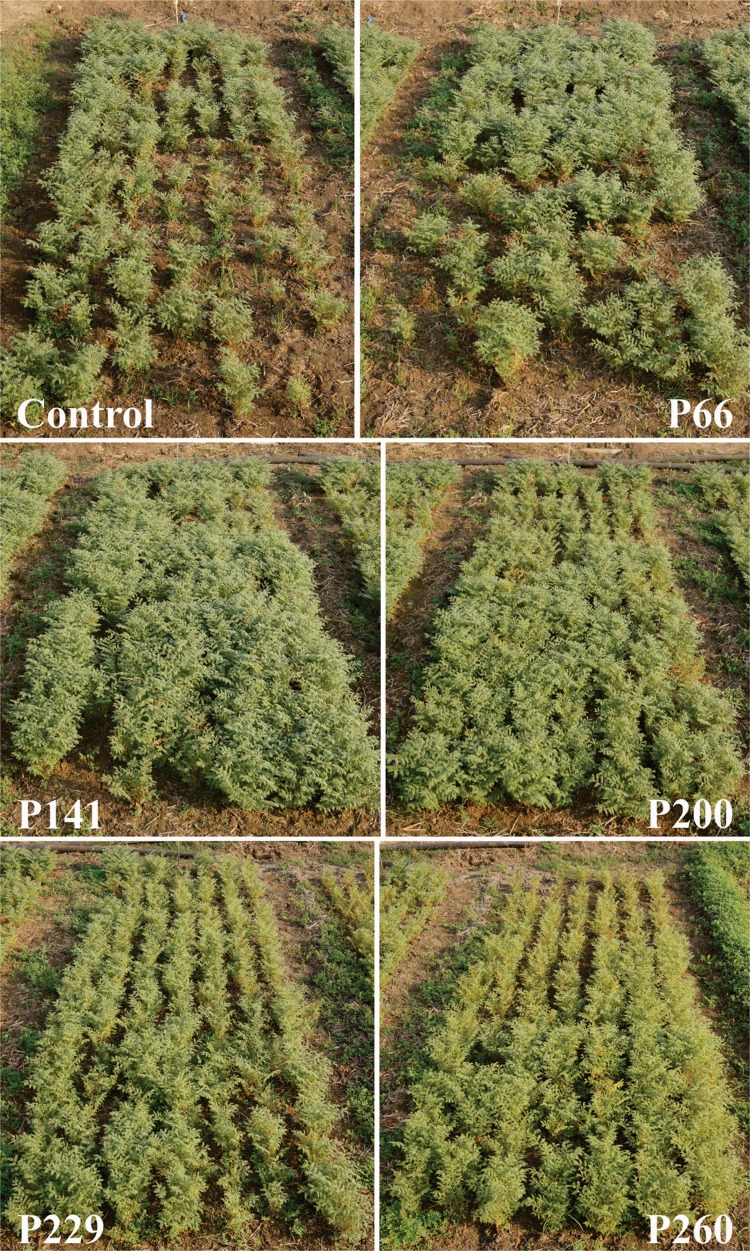

Efficacy of selected fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against root rot and yield of chickpea

Through confrontation assay, isolates P66 and P141 was identified to be having very strong antagonistic activities against R. solani and S. rolfsii, whereas P200 was antagonistic only against R. solani; other two isolates P229 and P260 were ineffective against both the pathogens. For field trials these five fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates were selected for their efficacy against collar rot disease and yield of chickpea. Frequency of infected plants was very high in untreated (control) plot, whereas seed treatment with bacterial isolates had lower incidence of collar rot (Table 2; Fig. 2). Vigorous plant growth was observed following seed bacterization with P141, P200, P240 (95.38, 83.04 and 78.86%, respectively), whereas poor vigour was observed with P229 (7.21%) and P260 (13.35%) (Table 2; Fig. 2). Bundle weight and yield indicated significant differences between control and treated plots. In the order of increasing bundle weight and yield per plot, the bioefficacy of the isolates were P260 < P229 < P66 < P200 < P141 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy of selected fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against collar rot and yield of chickpea

| Isolate no. | No. of plants | Plant vigour | Collar rot incidence | Bundle weight (kg) | Yield (gm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % poor vigour | % high vigour | % wilted plants | ||||

| Control | 256 | 92.820a ± 0.63 | 7.965e ± 0.155 | 35.015a ± 0.635 | 2.070 cd ± 0.25 | 598.000d ± 25 |

| P66 | 289 | 17.425d ± 0.465 | 83.585b ± 0.545 | 16.130b ± 0.21 | 3.670ab ± 0.45 | 1361.500b ± 59.5 |

| P141 | 303 | 5.130e ± 0.51 | 96.070a ± 0.69 | 11.105c ± 0.545 | 4.890a ± 0.43 | 1732.500a ± 10.5 |

| P200 | 350 | 21.625c ± 0.485 | 79.535c ± 0.675 | 7.275d ± 0.705 | 3.785ab ± 0.425 | 1085.000c ± 36 |

| P229 | 305 | 92.955a ± 0.165 | 7.820e ± 0.61 | 2.930e ± 0.31 | 2.735bc ± 0.355 | 574.500d ± 14.5 |

| P260 | 367 | 77.620b ± 0.51 | 14.000d ± 0.65 | 2.645e ± 0.465 | 1.425d ± 0.225 | 277.000e ± 34 |

| CV | 1.331 | 1.715 | 5.750 | 16.755 | 5.126 | |

| Fcal | 7145.771** | 5242.546** | 570.035** | 11.890** | 262.364** | |

| CD (0.01) | 5.529 | 3.062 | 2.668 | 1.923 | 178.267 | |

| CD (0.05) | 1.669 | 2.021 | 1.761 | 1.269 | 117.675 | |

Values after ± represent standard deviation

Superscript values indicate Duncan’s grouping means with the same letter are not significantly different

** Values are significant at 1 and 5% levels

Fig. 2.

Efficacy of selected fluorescent Pseudomonas isolates against collar rot and yield of chickpea

Discussion

Understanding of the mechanisms involved in the antagonist interactions between bacteria, pathogen and host plant is important for efficient utilization of these natural resources in crop health management.(Thomashow and Weller 1991). Siderophore production by strains of Pseudomonas spp., for plant disease control, is of great interest because of its possibilities in the substitution of chemical pesticides. Similarly, microbial cyanogenesis has been demonstrated in a few bacterial species (belonging to the genera Pseudomonas, Chromobacterium, Rhizobium and several cyanobacteria (Blumer and Haas 2000). Glycine has generally been used as a precursor of cyanide in fungi and bacteria (Brysk et al. 1969; Wissing 1974) and cyanogenesis is one of the mechanisms of antagonism and biocontrol properties (Haas and Défago 2005; Lanteigne et al. 2012). In the present study, we have compared the ability of several fluorescent Pseudomonads to produce siderophores, cyanogenesis and antagonism in plate assay. Our study revealed that the isolates vary in the mechanisms and ability to inhibit pathogens. During the study a simple confrontation assay technique was developed which was advantageous as compared to earlier reported techniques (Dennis and Webster 1971; Fokkema 1978; Santoyo et al. 2010), wherein bipartite interactions were performed on media plates by streaking bacterial bio-agents (forming quadrant) and placing mycelial plug of 4 mm in the centre. Our combined in vitro and field data show the potential of isolates P66, P141 and P200 to be developed as a commercial bioagent for the control of chickpea collar rot, a perennial problem in chickpea production compounded by the lack of host resistance against the pathogen S. rolfsii.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Arnow LE. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-tyrosine mixtures. J Biol Chem. 1937;118:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer C, Haas D. Mechanism, regulation, and ecological role of bacterial cyanide biosynthesis. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:170–177. doi: 10.1007/s002039900127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysk MM, Lauinger C, Ressler C. Biosynthesis of cyanide from [2–14C15N] glycine in chromobacterium violaceum. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Gen Subj. 1969;184:583–588. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito AM, Gagne S, Antoun H. Effect of compost on rhizosphere microflora of the tomato and on the incidence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:194–199. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.194-199.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C, Webster J. Antagonistic properties of species-groups of Trichoderma: I. Production of non-volatile antibiotics. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1971;57:25–IN3. [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema NJ. Fungal antagonisms in the phyllosphere. Ann Appl Biol. 1978;89:115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1978.tb02582.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BR. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol Res. 2014;169:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D, Défago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanteigne C, Gadkar VJ, Wallon T, et al. production of DAPG and HCN by Pseudomonas sp. LBUM300 Contributes to the biological control of bacterial canker of tomato. Phytopathology. 2012;102:967–973. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-11-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loper JE, Lindow SE. Lack of evidence for the in situ fluorescent pigment production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on bean leaf surfaces. Phytopathology. 1987;77:1449–1454. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-77-1449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza MS, Mehnaz S, Normand P, et al. Molecular characterization and PCR detection of a nitrogen-fixing Pseudomonas strain promoting rice growth. Biol Fertil Soils. 2006;43:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s00374-006-0074-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penrose DM, Glick BR. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol Plant. 2003;118:10–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, Paulitz TC, Steinberg C, et al. The rhizosphere: a playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil. 2009;321:341–361. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9568-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo G, Valencia-Cantero E, Orozco-Mosqueda M del C, et al. Papel de los sideróforos en la actividad antagónica de Pseudomonas fluorescens zum80 hacia hongos fitopatógenos (Role of siderophores in antagonistic activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens zum80 against phytopatogens) Terra Latinoam. 2010;28:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath PHA, Mair NS, Sharpe ME, Holt JG (1986) Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol 2. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD, p 964

- Thomashow LS, Weller DM. The rhizosphere and plant growth. Netherlands: Springer; 1991. Role of antibiotics and siderophores in biocontrol of take-all disease of wheat; pp. 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow LS, Weller DM. Plant-microbe interactions. US: Springer; 1996. Current concepts in the use of introduced bacteria for biological disease control: mechanisms and antifungal metabolites; pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JM. Distortion of fungal hyphae in the presence of certain inhibitors. Nature. 1947;159:850. doi: 10.1038/159850b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh UF, Morrissey JP, O’Gara F. Pseudomonas for biocontrol of phytopathogens: from functional genomics to commercial exploitation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:289–295. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, Kloepper JW, Tuzun S. Induction of systemic resistance of cucumber to Colletotrichum orbiculare by select strains of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology. 1991;81:1508–1512. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-81-1508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller DM. Pseudomonas biocontrol agents of soilborne pathogens: looking back over 30 years. Phytopathology. 2007;97:250–256. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-2-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissing F. Cyanide formation from oxidation of glycine by a Pseudomonas species. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:1289–1294. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.3.1289-1294.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]