Abstract

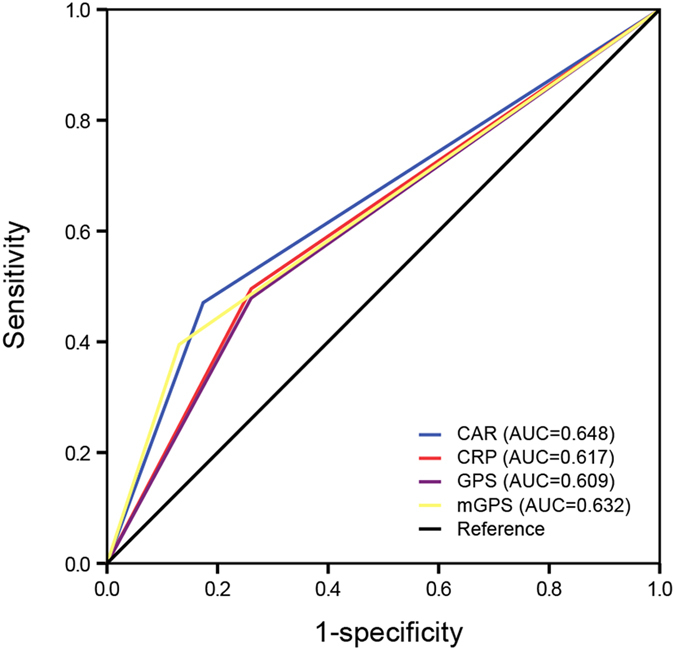

Although previous studies demonstrated that elevated C-reactive protein to albumin ratio (CAR) predicted poor prognosis in various solid tumors, little was known about the prognostic value of CAR in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (APC). The aim of the present study was to assess CAR as one independent prognostic factor in predicting overall survival (OS) in APC patients who had received palliative chemotherapy. Data of 142 APC patients who received palliative chemotherapy between 2009 and 2014 were retrospectively documented. We classified the patients into two groups based on the optimal cutoff value of CAR identified by generating receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. The clinicopathological parameters were compared between two CAR groups. Pearson correlation test showed that the level of C-reactive protein (CRP) was inversely correlated with albumin (r = −0.387; P < 0.001). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated overall survival (OS) was significantly longer in CAR < 0.156 group than CAR ≥ 0.156 group (11.2 vs 5.9 months, P < 0.001). CAR was an independent prognostic factor for OS in the Cox regression model (HR, 1.623; 95% CI, 1.093–2.410; P = 0.016). Furthermore, the discrimination ability of CAR (AUC = 0.648, P = 0.025) was slightly higher than that of other inflammation-based factors. Therefore, pretreatment CAR could be an independent prognostic biomarker for APC patients.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer-related mortality among both men and women globally. In more developed regions, the incidence rate of pancreatic cancer is 8.6 per 100,000 in males and 5.9 per 100,000 in females1. Even with curative resection, the 5-year overall survival rate is less than 5%2. Most patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease at the first diagnosis can only receive the palliative chemotherapy3. The prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer (APC) remains unsatisfactory.

Emerging evidence suggests the cancer-associated inflammation and nutritional status play a critical role in the progress of tumors4. Accordingly, previous studies identified several immunologically or nutritionally relevant biomarkers as prognostic factors for survival, such as CRP5–7, Glasgow prognostic score (GPS)8, modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS)9, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)10 and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)11. Among these, both GPS and mGPS are determined based on the serum concentration of CRP and albumin. As they are qualitative scores in nature, they may have the potential to cause underestimation (a lower CRP level) or overestimation (a lower albumin level) of the prognostic evaluation in cancer patients12.

Recently, a new prognostic index, CAR, has been reported as an independent prognostic factor in various tumors including pancreatic cancer12–18. Although CAR is also calculated based on the serum levels of CRP and albumin, it is a more quantitative parameter when compared with GPS or mGPS. In previous cohort study of the prognostic potential of CAR in pancreatic cancer, a large number of patients with resectable pancreatic cancer were enrolled18. Nevertheless, the prognostic value of CAR in APC patients who can only receive palliative chemotherapy has not been verified. Therefore, this study investigated CAR as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival (OS) in APC patients.

Methods

Patients

From 2009 to 2014, 142 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer (ICD, Tenth Revision, codes C25) were enrolled at the Department of Oncology and Pancreatic Cancer Center, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China). The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) without any concurrent cancer at another organ site; (2) with at least two cycles of palliative chemotherapy after the first diagnosis; (3) without any incomplete records of clinicopathological features; (4) pathologically confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Baseline clinicopathological characteristics were retrieved from electronic medical charts and summarized in Table 1. In 101 patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, 71 of them had liver metastasis and 30 of them had metastasis in other organs like lung, kidney and spleen. The CAR was calculated by dividing the serum CRP by the albumin obtained at the time of diagnosis. The GPS was determined as follows: the patients with a high CRP level (>10 mg/L) and a low albumin level (<35 g/L) were scored 2, those with either abnormality were given a score of 1 and those without any abnormal values were given a score of 019. Likewise, the mGPS is almost the same as that of GPS except that the patients with only a low albumin level were scored 0. Palliative chemotherapy regimens included gemcitabine monotherapy (n = 50)20, gemcitabine combination therapy (n = 45, including gemcitabine and oxaliplatin combination therapy21, gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy22, gemcitabine and erlotinib combination therapy23, gemcitabine and nab-paclitexal combination therapy24) and gemcitabine exclusive therapy (n = 47, including S-1 monotherapy25, nab-paclitexal monotherapy26 and FOLFIRINOX27). The average treatment cycles of first-line chemotherapy were 3.3. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and all experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committees of Shanghai General Hospital. And the methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Table 1.

Baseline clinicopathological characteristics of patients with APC.

| Valuables | Category | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 92 (64.8%) |

| Female | 50 (35.2%) | |

| Age | Median (Range) | 61 (34–86) |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 14 (9.9%) |

| 1 | 108 (76.1%) | |

| 2 | 20 (14.1%) | |

| Primary tumor location | Head and neck | 61 (43.0%) |

| Body and tail | 81 (57.0%) | |

| TNM stage | III | 41 (28.9%) |

| IV | 101 (71.1%) | |

| Liver metastasis | Yes | 71 (50.0%) |

| No | 71 (50.0%) | |

| Chemotherapy | Gemcitabine monotherapy | 50 (35.2%) |

| Gemcitabine combination therapy | 45 (31.7%) | |

| Gemcitabine exclusive therapy | 47 (33.1%) | |

| Albumin (g/L) | Median (Range) | 39.2 (26.1–48.4) |

| CRP (mg/L) | Median (Range) | 3.55 (0.2–178.0) |

| CAR | Median (Range) | 0.099 (0.004–5.266) |

| GPS | 0 | 79 (55.6%) |

| 1 | 47 (33.1%) | |

| 2 | 16 (11.3%) | |

| mGPS | 0 | 92 (64.8%) |

| 1 | 34 (23.9%) | |

| 2 | 16 (11.3%) | |

| AST (IU/L) | Median (Range) | 25.0 (7.3–1529.0) |

| ALT (IU/L) | Median (Range) | 20.9 (5.0–1300.0) |

| CA19–9 (U/ml) | Median (Range) | 430.45 (0.60–2084.00) |

| CEA (ng/ml) | Median (Range) | 6.57 (0.40–1065.00) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | Median (Range) | 122 (75–168) |

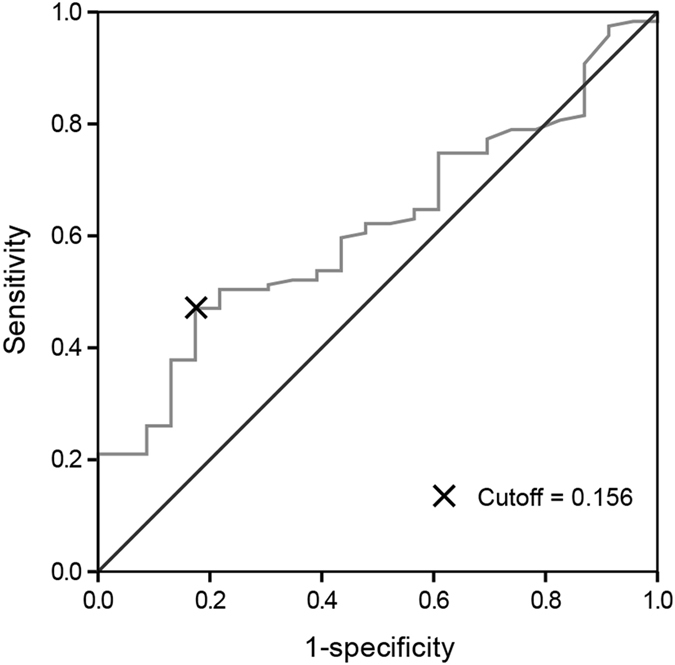

Cutoff values for CAR and other factors

There was no consistent cutoff value of CAR18, 28, thus it was identified by generating receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated as 0.62 (95% CI, 0.51–0.73) for the CAR (Fig. 1). The CAR of 0.156 corresponded to the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity on the ROC curve, which was equivalent to the maximization of Youden’s J statistics (J = sensitivity + specificity-1)29. For other factors, the cutoff values were their upper limit of normal values (AST, ALT and CEA) or those applied in other large trails (CA19–9 and hemoglobin) which were close to the median values of these factors30.

Figure 1.

Cutoff value of CAR assessed by ROC curve.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software (version 21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented as median and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). For the assessment of correlation between CAR and other valuables, patients were stratified into two groups according to different factors including gender (male and female), age (≥60 or <60 years), ECOG PS (0, 1 or 2), TNM stage (III or IV), liver metastasis (Yes or No), primary tumor location (head and neck or body and tail), chemotherapy (gemcitabine monotherapy or other therapies), CAR (≥0.156 or <0.156), Aspartate transaminase (AST) (≥40 IU/L or <40 IU/L), Alanine transaminase (ALT) (≥40 IU/L or <40 IU/L), Carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9) (≥1000 U/ml or <1000 U/ml), Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (≥5 ng/ml or <5 ng/ml) and hemoglobin (≥100 g/L or <100 g/L)31. Comparison between these groups was conducted using the Pearson Chi-Square test and Continuity Correction. The correlation between CRP and albumin was assessed by Pearson correlation test. OS was defined from the date of chemotherapy initiation to the date of death for any reason or censored to the last follow-up visit censored. Furthermore, survival analysis was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was used to investigate prognostic factors for OS. By conducting ROC curve, we evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of CAR, CRP, GPS and mGPS. For each factor, we calculated the HRs and corresponding 95% CIs. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline clinicopathological characteristics of patients with APC were summarized in Table 1. 82 patients had a pretreatment CAR of <0.156 while 60 patients had a pretreatment CAR of >0.156. We compared the clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups (Table 2). The percentages of patients with TNM stage IV, liver metastasis and AST ≥ 40 IU/L were significantly higher within the CAR ≥ 0.156 group (P < 0.05). However, percentages of patients with other variables were comparable between the two CAR groups.

Table 2.

Baseline clinicopathological characteristics according to CAR.

| Characteristics | CAR < 0.156 n = 82 | CAR ≥ 0.156 n = 60 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 49 (53.3%) | 43 (46.7%) | 0.142 |

| Female | 33 (66.0%) | 17 (34.0%) | |

| Age | |||

| <60 | 39 (63.9%) | 22 (36.1%) | 0.195 |

| ≥60 | 43 (53.1%) | 38 (46.9%) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 2 | 9 (45.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | 0.213 |

| 0–1 | 73 (59.8%) | 49 (40.2%) | |

| Primary tumor location | |||

| Head and neck | 35 (57.4%) | 26 (42.6%) | 0.938 |

| Body and tail | 47 (58.0%) | 34 (42.0%) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| III | 33 (80.5%) | 8 (19.5%) | <0.001 |

| IV | 49 (48.5%) | 52 (51.5%) | |

| Liver metastasis | |||

| Yes | 35 (49.3%) | 36 (50.7%) | 0.041 |

| No | 47 (66.2%) | 24 (33.8%) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Gemcitabine monotherapy | 31 (62.0%) | 19 (38.0%) | 0.449 |

| Others | 51 (55.4%) | 41 (44.6%) | |

| AST (IU/L) | |||

| <40 | 60 (63.8%) | 34 (36.2%) | 0.040 |

| ≥40 | 22 (45.8%) | 26 (54.2%) | |

| ALT (IU/L) | |||

| <40 | 63(59.4%) | 43 (40.6%) | 0.485 |

| ≥40 | 19 (52.8%) | 17 (47.2%) | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | |||

| <1000 | 51 (60.0%) | 34 (40.0%) | 0.507 |

| ≥1000 | 31 (54.4%) | 26 (45.6%) | |

| CEA (ng/ml) | |||

| <5 | 36 (64.3%) | 20 (35.7%) | 0.203 |

| ≥5 | 46 (53.5%) | 40 (46.5%) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | |||

| <120 | 33 (51.6%) | 31 (48.4%) | 0.177 |

| ≥120 | 49 (62.8%) | 60 (42.3%) | |

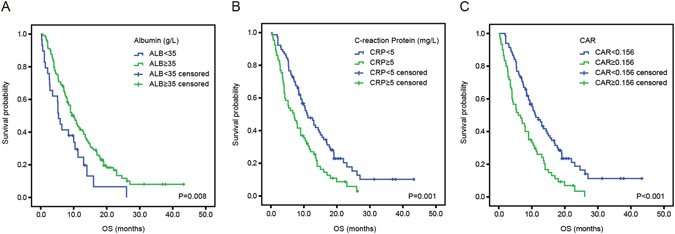

Comparison of OS stratified by pretreatment albumin, CRP and CAR

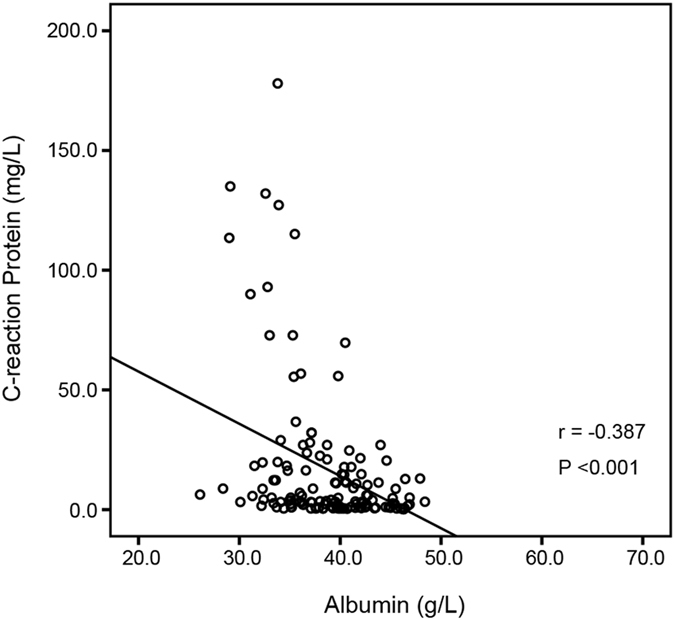

Pearson correlation test demonstrated that the level of CRP was inversely correlated with the level of albumin (r = −0.387; P < 0.001, Fig. 2). In the the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the median OS of patients with albumin < 35 g/L was 5.4 (95% CI: 4.3–6.5) months which was significantly shorter than 10.0 (95% CI: 8.1–11.9) months of patients with albumin ≥35 g/L (P = 0.008, Fig. 3A). Likewise, patients with CRP ≥ 5 mg/L have a poorer OS compared to those with CRP < 5 mg/L (7.0 months vs. 11.0 months, P = 0.001, Fig. 3B). Moreover, the median OS was 11.2 (95% CI: 8.5–13.9) months in CAR < 0.156 group and 5.9 (95% CI:3.0–8.8) months in CAR ≥ 0.156 group (hazard ratio (HR) 2.004, 95% CI: 1.389–2.891; P < 0.001, Fig. 3C).

Figure 2.

The correlation between CRP and albumin.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival according to the level of serum albumin (A), CRP (B) and CAR (C).

Prognostic factors for OS

In univariate analysis, five variables of ECOG PS (P = 0.005), TNM stage (P < 0.001), CAR (P < 0.001), AST (P = 0.024) and CA19-9 (P < 0.001) correlated with OS were identified. All these factors were subsequently analyzed in multivariate analysis. Consequently, TNM stage (P = 0.015), CAR (P = 0.016) and CA19- 9 (P = 0.001) were found to be independent prognostic factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of poor prognostic factors for OS in APC patients.

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.988 | 0.673–1.452 | 0.952 | |||

| Female | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| <60 | 0.876 | 0.609–1.259 | 0.475 | |||

| ≥60 | ||||||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 2 | 2.011 | 1.233–3.280 | 0.005 | 1.524 | 0.886–2.261 | 0.128 |

| 0–1 | ||||||

| Primary tumor location | ||||||

| Head and neck | 1.375 | 0.948–1.996 | 0.093 | |||

| Body and tail | ||||||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| IV | 2.163 | 1.415–3.307 | <0.001 | 1.762 | 1.121–2.771 | 0.014 |

| III | ||||||

| Liver metastasis | ||||||

| Yes | 1.999 | 1.382–2.891 | < 0.001 | |||

| No | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Gemcitabine monotherapy | 0.831 | 0.573–1.207 | 0.331 | |||

| Others | ||||||

| CRP (mg/L) | ||||||

| ≥5 | 1.793 | 1.245–2.580 | 0.002 | |||

| <5 | ||||||

| Albumin (g/L) | ||||||

| ≥35 | 0.553 | 0.354–0.866 | 0.010 | |||

| <35 | ||||||

| CAR | ||||||

| ≥0.156 | 2.004 | 1.389–2.891 | <0.001 | 1.629 | 1.097–2.419 | 0.016 |

| <0.156 | ||||||

| GPS | ||||||

| 2 | 1.539 | 1.201–1.971 | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | ||||||

| 0 | ||||||

| mGPS | ||||||

| 2 | 1.437 | 1.121–1.844 | 0.004 | |||

| 1 | ||||||

| 0 | ||||||

| AST (IU/L) | ||||||

| ≥40 | 1.560 | 1.059–2.297 | 0.024 | 0.937 | 0.604–1.453 | 0.771 |

| <40 | ||||||

| ALT (IU/L) | ||||||

| ≥40 | 1.087 | 0.713–1.658 | 0.697 | |||

| <40 | ||||||

| CA19–9 (U/ml) | ||||||

| ≥1000 | 1.989 | 1.359–2.911 | <0.001 | 1.973 | 1.332–2.924 | 0.001 |

| <1000 | ||||||

| CEA (ng/ml) | ||||||

| ≥5 | 1.380 | 0.948–2.010 | 0.092 | |||

| <5 | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | ||||||

| <120 | 0.887 | 0.618–1.274 | 0.516 | |||

| ≥120 | ||||||

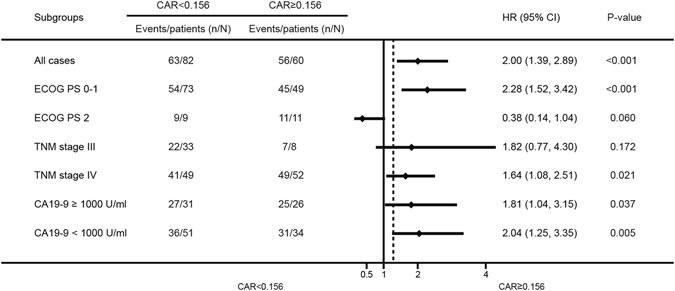

Subgroup analysis and discrimination ability of CAR

CAR was significantly correlated with OS in the subgroup identified by CA19-9. However, CAR demonstrated no correlation with OS in the subgroup of patients with ECOG PS 2 or TNM stage III (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Hazard ratios (HRs) of CAR in different patient subgroups identified by ECOG PS, TNM stage and CA19-9. HRs >1.0 indicate a worse outcome.

ROC curves were used to evaluate the discrimination ability of CAR and other inflammation-based factors including CRP, GPS and mGPS (Fig. 5). The discrimination ability of CAR, as assessed by AUC, was 0.648 (P = 0.025), which was the highest among these inflammation-based factors (CRP 0.617, GPS 0.615, and mGPS 0.632).

Figure 5.

The predictive ability of the four inflammation-based prognostic scores was compared by ROC curves.

Discussion

In the present study, pretreatment CAR was found to be an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in APC patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Haruki, et.al showed that elevated pretreatment CAR predicted poor clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients with resectable tumors in 201618. More recently, Mengwan Wu, et.al investigated the prognostic value of CAR in pancreatic cancer patients treated with or without chemotherapy28. However, there was optimal difference in the cutoff values of CAR identified in these two study, which could be explained by the different populations of patients enrolled in two studies.To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the prognostic value of CAR in a cohort of APC patients receiving palliative chemotherapy.

Systemic inflammation response plays a vital role in the progression of pancreatic cancer. Various prognostics scoring models assessed by peripheral blood cell count or inflammatory factors were developed retrospectively to stratify the optimal pancreatic cancer patients receiving palliative care32. However, little has been used predicatively in clinical practice.

CRP, a marker of inflammation, was correlated with survival outcomes in various cancers, including pancreatic cancer6, 7, 33. On the other hand, hypoalbuminemia, an indicator for chronic malnutrition, is also a common complication for advanced cancer patients. Therefore, the CAR, a combined pattern of both CRP and albumin, may reveal the outcome of pancreatic cancer in a better way. Haruki, et.al found that patients in high CAR group happened to be in more advanced TNM stage (p = 0.007). Such finding was consistent with this study as the percentages of patients with TNM stage IV, liver metastasis and AST ≥ 40 IU/L were significantly higher within the CAR ≥ 0.156 group than CAR < 0.156 group (P < 0.05), which may have reflected the poorer status of patients with this disease. However, after adjustment for TNM stage, AST, ECOG PS and CA19-9 in multivariate analysis, the CAR < 0.156 remained favorable independent of prognostic factor, with a clinically relevant HR value (HR 1.629, 95% CI 1.097–2.419; P = 0.016), which suggested the different prognosis of CAR stratification was not merely attribute to the difference in baseline characteristics between the two groups. Furthermore, the subgroup analysis of CAR in patients with TNM stage IV also demonstrated the prognostic value of CAR regardless of TNM stage (HR: 1.64, 95% CI 1.08–2.51; P = 0.021). Our study also showed there was a reciprocal relationship between CRP and albumin (r = −0.387, P < 0.001, Fig. 2). This is consistent with Hwang JC’s work34 and can be partly explained by the reason that inflammation reduces albumin concentration by decreasing its synthesis rate35. In addition, immunonutrition can also suppress the inflammatory response36.

Previous studies revealed that GPS or mGPS could be independent prognostic factors in pancreatic cancer patients37–39. However, in this study, CAR showed superior discrimination ability than other inflammation-based scores including GPS and mGPS in pancreatic cancer patients, which was consistent with the results of several studies conducted among patients with other cancers types12, 14. Furthermore, Haruki, et.al also found CAR (P = 0.035), rather than mGPS (P = 0.091), was independent and significant predictor of the OS. This may be partially explained by the reason that CAR is a simple ratio with a continuous range of values but both GPS and mGPS, consisting of dichotomized variables, have a qualitative nature with discontinuous values.

The subgroup analysis (Fig. 4) showed that the prognostic value of CAR in high CA19-9 or low CA19-9 patients were also identified respectively. This means that the CAR with cutoff value of 0.156 may also stratify high or low CA19-9 patients into two groups with prominent difference in OS.

There are several strengths of this study. First, this study boasts a cohort with long follow-up period. Second, CAR is a biomarker that can be utilized in clinical practice as the measurement of CAR is non-invasive, easy to acquire and affordable for the patients. Several limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. One potential limitation is that it is a retrospective and single-center study with relatively small sample size which may cause selection bias. Second, this study mainly focused on the pretreatment CAR which may be largely affected by other factors like infection or cancer complication. Third, heterogeneous treatments in this study may affect survival outcome although we found chemotherapy was not correlated with OS in this study as some other studies had reported10, 40. Both CRP and albumin are produced in liver and various chemotherapy regimens have different effects on patients’ liver function and inflammation status, which may affect the production of CRP and albumin. Another limitation is the lack of a validation cohort to confirm the cutoff and prognostic value of CAR. Therefore, future study on a larger sample size and same treatment modality should be conducted to verify the findings in this study. Finally, the concrete mechanisms underlying the prognostic value of CAR should be further investigated.

In conclusion, this study indicates that the pretreatment CAR could be an independent prognostic biomarker for APC patients.

Acknowledgements

The National Science Foundation of China supported this work [Grant Number: 81502017, 81502018, 81572315, 81171887 and 91229117]

Author Contributions

The study was conceived and designed by J.H., P.X. and L.W.. Acquisition and analysis of data was performed by J.H., H.Y., Y.Z., D.C., S.L. and S.R. In addition, P.X. L.Z. and W.H. interpreted the data. J.H., P.X. and L.W. drafted the article, and all authors revised the article and approved the final version to be published.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Junjie Hang, Peng Xue and Haiyan Yang contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Torre LA, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2004;363:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinemann V, Haas M, Boeck S. Systemic treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer treatment reviews. 2012;38:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crusz SM, Balkwill FR. Inflammation and cancer: advances and new agents. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology. 2015;12:584–596. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pine JK, et al. Serum C-reactive protein concentration and the prognosis of ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2009;35:605–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szkandera J, et al. Validation of C-reactive protein levels as a prognostic indicator for survival in a large cohort of pancreatic cancer patients. British journal of cancer. 2014;110:183–188. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrotriya S, Walsh D, Bennani-Baiti N, Thomas S, Lorton C. C-Reactive Protein Is an Important Biomarker for Prognosis Tumor Recurrence and Treatment Response in Adult Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review. PloS one. 2015;10:e0143080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namiuchi S, et al. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score as a prognostic factor in patients with acute heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2015;16:409–415. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proctor M, et al. An inflammation-based prognostic score (mGPS) predicts cancer survival independent of tumour site: a Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. British journal of cancer. 2011;104:726–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue P, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting palliative chemotherapy outcomes in advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer medicine. 2014;3:406–415. doi: 10.1002/cam4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi Q, Geng Y, Sun M, Wang P, Chen Z. Clinical implications of systemic inflammatory response markers as independent prognostic factors for advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology: official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP)… [et al.] 2015;15:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, et al. Preoperative C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio Predicts Prognosis of Patients after Curative Resection for Gastric Cancer. Translational oncology. 2015;8:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishizuka M, et al. Clinical Significance of the C-Reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio for Survival After Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016;23:900–907. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei XL, et al. A novel inflammation-based prognostic score in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio. BMC cancer. 2015;15:350. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1379-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita A, et al. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, a novel inflammation-based prognostic score, predicts outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology. 2015;22:803–810. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu XL, Yu HQ, Hu W, Song Q, Mao WM. A Novel Inflammation-Based Prognostic Score, the C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio Predicts the Prognosis of Patients with Operable Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PloS one. 2015;10:e0138657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou, T. et al. Ratio of C-Reactive Protein/Albumin is An Inflammatory Prognostic Score for Predicting Overall Survival of Patients with Small-cell Lung Cancer. Scientific reports 5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Haruki, K. et al. The C-reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio Predicts Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer After Pancreatic Resection. World journal of surgery, 10.1007/s00268-016-3491-4 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Horie T, Kubota K. Inflammation-based prognostic score is a novel predictor of postoperative outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Annals of surgery. 2007;246:1047–1051. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181454171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burris HA, 3rd, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louvet C, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura K, et al. Phase II trial of oral S-1 combined with gemcitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer. British journal of cancer. 2006;94:1575–1579. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore MJ, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Von Hoff DD, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okusaka T, et al. A late phase II study of S-1 for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2008;61:615–621. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosein PJ, et al. A phase II trial of nab-Paclitaxel as second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. American journal of clinical oncology. 2013;36:151–156. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182436e8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conroy T, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu M, Guo J, Guo L, Zuo Q. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts overall survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37:12525–12533. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Budczies J, et al. Cutoff Finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PloS one. 2012;7:e51862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas M, et al. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2013;139:681–689. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas M, et al. Prognostic relevance of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, and LDH kinetics in patients treated with palliative second-line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2010;31:351–357. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le N, Sund M, Vinci A. Prognostic and predictive markers in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2016;48:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishi T, et al. Pretreatment C-reactive protein level predicts outcome and patterns of failure after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology: official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP)… [et al.] 2015;15:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang JC, Jiang MY, Lu YH, Wang CT. Precedent fluctuation of serum hs-CRP to albumin ratios and mortality risk of clinically stable hemodialysis patients. PloS one. 2015;10:e0120266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Don BR, Kaysen G. Serum albumin: relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Seminars in dialysis. 2004;17:432–437. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giger U, et al. Preoperative immunonutrition suppresses perioperative inflammatory response in patients with major abdominal surgery-a randomized controlled pilot study. Annals of surgical oncology. 2007;14:2798–2806. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.La Torre M, et al. The glasgow prognostic score as a predictor of survival in patients with potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology. 2012;19:2917–2923. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morinaga S, et al. Glasgow Prognostic Score Predicts Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Gemcitabine Monotherapy After Curative Surgery. Anticancer research. 2015;35:4865–4870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imaoka H, et al. Evaluation of Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score for Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Pancreas. 2016;45:211–217. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueno H, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1640–1648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]