Abstract

Introduction

African Americans (AA) compared to European Americans (EA) have poorer stage specific survival from colorectal cancer (CRC). Recent reports have indicated that the racial difference in survival has worsened over time, especially among younger patients. To better characterize this association, we used population-based SEER registry data to evaluate the impact of race on stage IV CRC survival in patients < 50 and ≥ 50.

Patients and Methods

The population was comprised of 16,782 patients diagnosed with stage IV colon and rectal adenocarcinoma between 01 January 2004 and 31 December 2011. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the association between race and other prognostic factors and the risk of death in each age group.

Results

Younger AAs compared to EAs had a higher prevalence of proximal CRC at diagnosis, a factor associated with significantly higher risk of death in both races. Among patients < 50 years of age, AAs had a higher risk of death compared to EAs (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.51)), which was attenuated in patients ≥ 50 years of age (HR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.16); p for interaction 0.01.

Conclusion

The results revealed poor overall survival in AA compared to EA, especially in those < 50 years of age. The higher prevalence of proximal CRC at diagnosis among younger aged AA (vs. EA) may contribute to the racial difference in survival. Future studies will be needed to understand how colonic location impacts the efficacy of treatment regimens.

Keywords: race, survival, metastatic, colon cancer, early onset

Introduction

African Americans (AA) compared to European Americans (EA) have higher colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and poorer stage-specific survival (1, 2). For most Americans, survival has improved significantly over the past twenty years, but for AAs the rates have improved more slowly, especially among those with advanced disease stages (3, 4). Unfortunately, younger AAs appear to be more vulnerable to CRC as the relative difference in survival by race is more pronounced in younger compared to older patients (5–7).

A primary reason for improvement in stage IV colorectal cancer survival is due to better treatment options. Since the introduction of combination chemotherapy and biologic agents in 2004, median survival for stage IV CRC has increased from approximately 10 months in the mid-1990s to 20 months in 2008 (8, 9). In our previous study (5), we found that the racial disparity in advanced CRC had worsened over time, especially among younger age AAs compared to EAs diagnosed post 2003. One of the reasons for the poorer survival in AAs compared to EAs may be due to the higher prevalence of proximal neoplasia in AAs (10–15), which is often associated with worse survival (16–19), especially in the context of metastatic disease. A recent investigation has found that treatment with biologic agents appears to be less effective in patients with proximal CRC compared to distal or rectal cancer (20).

In our previous study, we had a limited number of cases younger than 50 years of age and only two years of CRC case data after the introduction of the biologic therapies. Therefore, in the present analysis we took advantage of the population-based SEER registry data to investigate racial differences in CRC survival in younger (< 50 years) and older (≥ 50 years) cases diagnosed with stage IV CRC after 2003. Our analysis focused on stage IV cases from 2004–2011 for several reasons, including: similar standard recommended treatment guidelines, a large relative difference in survival by race in stage IV CRC and a high proportion of cases dying from CRC rather than competing causes. We also investigated whether clinical or pathologic factors at diagnosis (colonic location, histology, grade, elevated CEA) differ by race and help to explain differences observed in survival.

Materials and Methods

Study population

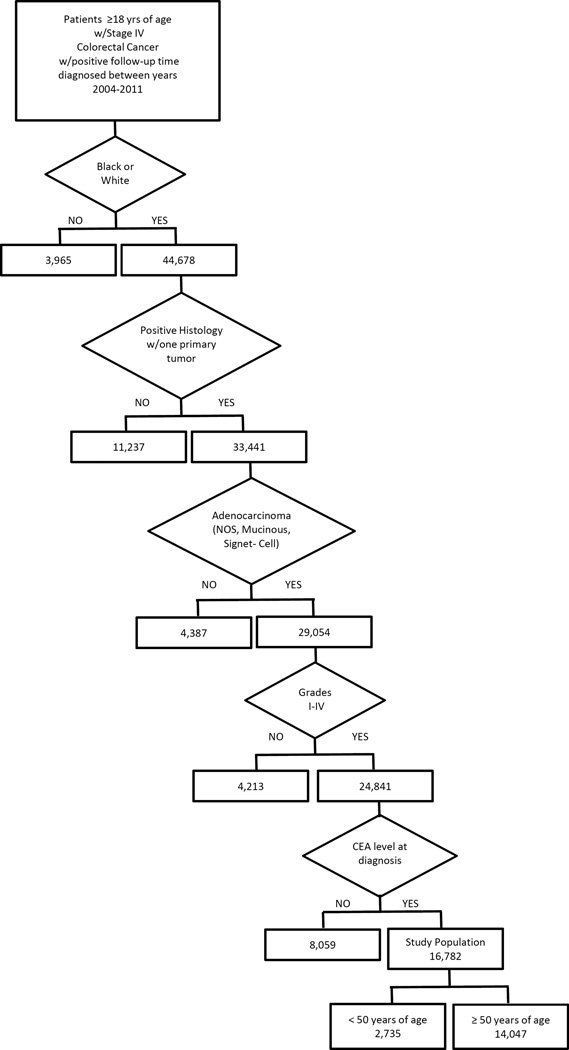

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute is a population-based data system that collects cancer incidence in 18 regions within the USA. The mortality data reported by SEER are provided by the National Center for Health Statistics. For our analysis, the study population was comprised of adults (≥18 years of age) with pathologically documented colon and rectal adenocarcinoma cases in the SEER registry diagnosed between 01 January 2004 and 31 December 2011 with positive follow-up time (> 0 days). SEER codes cancer stage using SEER staging criteria defined as local, regional, or distant disease, and we further limited the study population to include only cases who presented with distant disease (equivalent to TNM stage IV), which includes disease detected at lymph nodes or other distant sites. We used the following additional case selection criteria to further define the study population: single primary tumor only; AA or EA race; tumor histology reported as adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), mucinous adenocarcinoma, or signet ring cell adenocarcinoma; tumor grade reported as well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated (grades I, II, III or IV, respectively); colonic location proximal (cecum, ascending colon, or hepatic flexure transverse colon); distal (splenic flexure, descending colon, or sigmoid colon); or rectal (recto-sigmoid, or rectum); and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) serum level at diagnosis, either normal or elevated. Cases with variable values other than those specified (including missing or unknown values) were excluded from the final analysis set (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart detailing exclusion criteria and number of cases dropped for each clinical or pathologic variable.

Statistical considerations

Data analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4) and R (version 3.1.2) (21). All analyses were performed using data stratified by age at diagnosis (<50 versus ≥50 years of age) and gender, with primary comparisons within strata being those between EA and AA cases. Univariate associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with race were evaluated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables.

Overall survival was calculated as the time (in months) from diagnosis with distant stage CRC to death from any cause. Survival times for cases alive as of 31 December 2011 were censored at the end of follow-up. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate median survival time, five year survival probabilities, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Comparisons between survival curves were performed using log-rank tests.

Factors’ associations with survival were evaluated by fitting Cox proportional hazards (CPH) regression models. Because of the significant interaction between age category and race, we fit separate CPH regression models for the two age groups. The p for interaction for both univariate and multivariable CPH models was 0.01. We first fit univariate CPH models investigating unadjusted associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and survival. We then fit multivariable CPH models with independent variables of age (as a continuous variable), race and gender (model 1); and additionally, colonic location, tumor grade, histologic type, and CEA elevation status (model 2). Finally, we further stratified by gender, and fit all univariate and multivariable CPH models described (with gender removed as an independent variable). Associations were summarized using hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

The population was comprised of 85% EAs (n= 14182) and 15% AAs (n=2600), resulting in 16,782 cases available for analysis. Among the 2735 cases under the age of 50, 82% were EA and 18% AA, and among the 14047 cases fifty years of age or older, 85% were EA and 15% AA. Also, of the 8932 males, 86% were EA and 14% AA, and of the 7750 females, 83% were EA and 17% AA. Overall, survival was better in younger compared to older cases irrespective of race. Among the AA group, those under the age of 50 had a median survival of 20 months (18 to 22 months) compared to 13 months (12 to 14 months) for those 50 years of age and older. Similarly, in the EA group, the median survival for the younger group was 25 months (24 to 26 months) compared to 14 months (14 to 15 months) for the older group.

Under age 50

Overall, 19% of AA cases diagnosed with CRC were under the age of 50 compared to 16% of EAs (Table 1). In this age group, several pathologic features differed significantly at diagnosis by race. These include tumor location, tumor grade, and CEA level. Specifically, the prevalence of proximal CRC was 17% higher in AAs women than EA women and 9% higher in AA men than EA men. In contrast, rectal cancer was 10% lower in AA women than EA women and 9% lower in AA men than their EA counterparts. CEA positivity was 6% higher in both AA men and women than their EA counterparts. The prevalence of high-grade tumors in AA and EA males was 24% and 33%, respectively. No significant differences were observed in histologic types.

Table 1.

Univariate associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with gender and race for younger (<50 years) and older (≥ 50 years) patients.

| Age < 50 years | |||||||

| Characteristica | Male (n=1467) | Pb | Female (n=1268) | Pb | |||

| EA (n=1204) |

AA (n=263) |

EA (n=1033) |

AA (n=235) |

||||

| Age (years) | 44(18–49) | 45(19–49) | 0.51 | 44(18–49) | 44(21–49) | 0.14 | |

| Colonic Location | 0.004 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Distal | 416(35) | 91(35) | 432(42) | 83(35) | |||

| Proximal | 281(23) | 85(32) | 272(26) | 100(43) | |||

| Rectal | 507(42) | 87(33) | 329(32) | 52(22) | |||

| Tumor Grade | 0.005 | 0.16 | |||||

| Low | 808(67) | 200(76) | 708(69) | 172(73) | |||

| High | 396(33) | 63(24) | 325(31) | 63(27) | |||

| Histologic Type | 0.97 | 0.43 | |||||

| Adeno NOS | 1073(89) | 235(89) | 919(89) | 213(91) | |||

| Mucinous | 86(7) | 19(7) | 74(7) | 17(7) | |||

| Signet Cell | 45(4) | 9(3) | 40(4) | 5(2) | |||

| CEA Antigen | 0.02 | 0.05 | |||||

| Normal | 240(20) | 36(14) | 216(21) | 36(15) | |||

| Elevated | 964(80) | 227(86) | 817(79) | 199(85) | |||

| Age ≥ 50 years | |||||||

| Male (n=7565) | Female (n=6482) | ||||||

| EA (n=6534) |

AA (n=1031) |

Pb | EA n=5411) |

AA (n=1071) |

Pb | ||

| Age (years) | 65(50–98) | 62(50–94) | <0.0001 | 69(50–103) | 65(50–108) | <0.0001 | |

| Colonic Location | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Distal | 2029(31) | 333(32) | 1535(28) | 321(30) | |||

| Proximal | 2499(38) | 447(43) | 2607(48) | 572(53) | |||

| Rectal | 2006(31) | 251(24) | 1269(23) | 178(17) | |||

| Tumor Grade | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Low | 4623(71) | 793(77) | 3649(67) | 829(77) | |||

| High | 1911(29) | 238(23) | 1762(33) | 242(23) | |||

| Histologic Type | <0.0001 | 0.10 | |||||

| Adeno NOS | 5913(91) | 977(95) | 4852(90) | 965(90) | |||

| Mucinous | 477(7) | 43(4) | 453(8) | 95(9) | |||

| Signet Cell | 144(2) | 11(1) | 106(2) | 11(1) | |||

| CEA Antigen | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Normal | 1293(20) | 136(13) | 1024(19) | 128(12) | |||

| Elevated | 5241(80) | 895(87) | 4387(81) | 943(88) | |||

Column percents may not total 100 % due to rounding

Descriptive measures are median (range) for age, and frequency (%) for all others

p value is based on Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test for age-race association and a chi-square test for all others

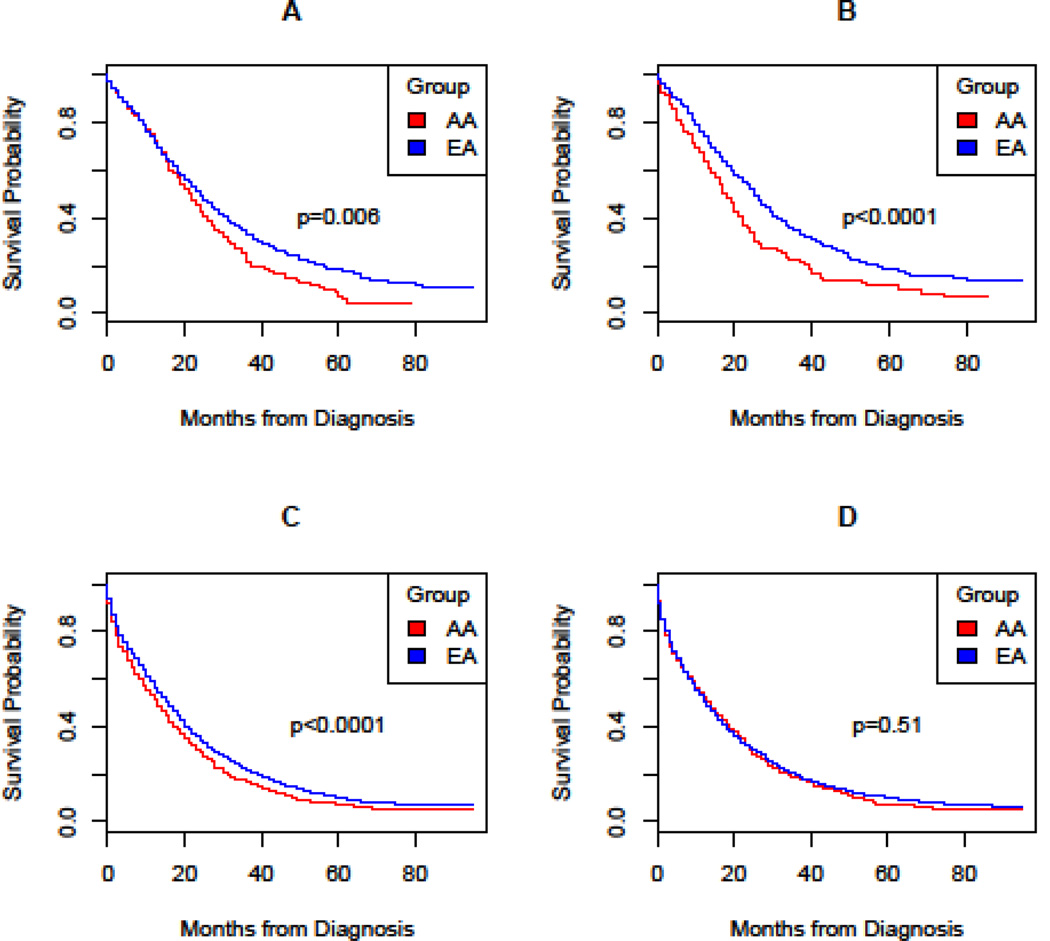

Median survival was lower in AAs compared to EA (Table 2, Figure 1). Relative to EA women, AA women had significantly worse survival (18 months versus 25 months) and lower 5 year survival rates (0.12 versus 0.18; log rank p<0.0001). For both AA and EA women, median survival was lowest among those with proximal neoplasia (Table 2). AA women with distal and rectal disease experienced worse survival than EA women (21 versus 27 months, distal; 17 versus 29 months, rectal). Based on stratified Cox regression analysis (Table 3), AA women compared to EA women had significantly higher risk of death (HR= 1.48, 95% CI =1.25 to 1.75). Adjustment for clinicopathologic covariates slightly attenuated the risk (HR= 1.39, 95% CI =1.17 to 1.65).

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier median survival time and survival probability estimates by age, gender, colonic location and race.

| Age | Gender | Colonic Location |

Race | n | *ne | Prevalence (%) |

†M (mos) |

†M 95% CI |

‡P(S) | P(S) 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

<50 years | |||||||||

| Male | Distal | EA | 416 | 241 | 35 | 26 | (23,31) | 0.20 | (0.15, 0.27) |

|

| AA | 91 | 65 | 35 | 25 | (20,31) | 0.02 | (0.00, 0.14) |

|||

| Proximal | EA | 281 | 191 | 23 | 19 | (16,23) | 0.16 | (0.11, 0.22) |

||

| AA | 85 | 60 | 32 | 18 | (15,25) | 0.09 | (0.03, 0.22) |

|||

| Rectal | EA | 507 | 312 | 42 | 26 | (23,29) | 0.18 | (0.14, 0.24) |

||

| AA | 87 | 60 | 33 | 21 | (14,23) | 0.14 | (0.06, 0.31) |

|||

| OVERALL | EA | 1204 | 744 | 24 | (23,26) | 0.18 | (0.15, 0.22) |

|||

| AA | 263 | 185 | 22 | (19,24) | 0.07 | (0.04, 0.14) |

||||

| Female | Distal | EA | 432 | 257 | 42 | 27 | (25,32) | 0.17 | (0.13, 0.23) |

|

| AA | 83 | 58 | 35 | 21 | (18,27) | 0.14 | (0.07, 0.28) |

|||

| Proximal | EA | 272 | 196 | 26 | 17 | (14,20) | 0.17 | (0.12, 0.23) |

||

| AA | 100 | 69 | 43 | 15 | (12,20) | 0.09 | (0.04, 0.23) |

|||

| Rectal | EA | 329 | 188 | 32 | 29 | (27,33) | 0.21 | (0.16, 0.29) |

||

| AA | 52 | 41 | 22 | 17 | (15,22) | 0.12 | (0.05, 0.27) |

|||

| OVERALL | EA | 1033 | 641 | 25 | (24,27) | 0.18 | (0.15, 0.22) |

|||

| AA | 235 | 168 | 18 | (16,20) | 0.12 | (0.08, 0.19) |

||||

|

Age |

≥50 years | |||||||||

| Male | Distal | EA | 2029 | 1450 | 31 | 19 | (17,20) | 0.12 | (0.10, 0.14) |

|

| AA | 333 | 250 | 32 | 14 | (12,18) | 0.10 | (0.06, 0.15) |

|||

| Proximal | EA | 2499 | 1957 | 38 | 12 | (11,12) | 0.08 | (0.07, 0.10) |

||

| AA | 447 | 358 | 43 | 11 | (9,13) | 0.05 | (0.03, 0.09) |

|||

| Rectal | EA | 2006 | 1407 | 31 | 18 | (17,20) | 0.11 | (0.09, 0.13) |

||

| AA | 251 | 186 | 24 | 15 | (11,17) | 0.08 | (0.04, 0.13) |

|||

| OVERALL | EA | 6534 | 4814 | 16 | (15,16) | 0.10 | (0.09, 0.11) |

|||

| AA | 1031 | 794 | 13 | (11,14) | 0.07 | (0.05, 0.10) |

||||

| Female | Distal | EA | 1535 | 1107 | 28 | 17 | (16,19) | 0.13 | (0.11, 0.15) |

|

| AA | 321 | 237 | 30 | 16 | (12,20) | 0.07 | (0.04, 0.13) |

|||

| Proximal | EA | 2607 | 2079 | 48 | 10 | (9,11) | 0.09 | (0.08, 0.11) |

||

| AA | 572 | 450 | 53 | 13 | (11,14) | 0.07 | (0.05, 0.11) |

|||

| Rectal | EA | 1269 | 942 | 23 | 14 | (13,16) | 0.10 | (0.08, 0.13) |

||

| AA | 178 | 134 | 17 | 15 | (11,21) | 0.07 | (0.03, 0.16) |

|||

| OVERALL | EA | 5411 | 4128 | 13 | (12,13) | 0.10 | (0.09, 0.11) |

|||

| AA | 1071 | 821 | 14 | (12,15) | 0.07 | 0.05, 0.10) |

||||

ne= number of events;

M=median;

P(S) = five-year survival probability

Table 3.

Summary of results from Cox proportional hazards regression models

| Cases < 50 years | Cases ≥50 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n=1467 | Female n=1268 | Male n=7565 | Female n=6482 | ||||||

| Variable | Level | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Agea | 0.89 (0.80, 1.00) |

0.94 (0.84, 1.05) |

0.96 (0.86, 1.07) |

0.97 (0.87, 1.08) |

1.33 (1.30, 1.37) |

1.34 (1.30, 1.37) |

1.39 (1.35, 1.42) |

1.37 (1.34,1.42) |

|

| Race | EA | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| AA | 1.25 (1.06, 1.47) |

1.29 (1.10, 1.52) |

1.48 (1.25, 1.75) |

1.39 (1.17, 1.65) |

1.18 (1.09, 1.27) |

1.24 (1.15, 1.34) |

1.03 (0.95, 1.11) |

1.09 (1.01,1.18) |

|

| Colonic Location | Distal | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Proximal | 1.30 (1.10, 1.54) |

1.17 (0.99, 1.40) |

1.46 (1.24), 1.72) |

1.34 (1.13, 1.58) |

1.36 (1.28, 1.45) |

1.27 (1.19, 1.35) |

1.35 (1.26, 1.44) |

1.17 (1.09,1.25) |

|

| Rectal | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) |

1.07 (0.92, 1.24) |

0.96 (0.81, 1.14) |

1.01 (0.85, 1.19) |

0.98 (0.92, 1.05) |

1.04 (0.97, 1.11) |

1.06 (0.98, 1.15) |

1.03 (0.95,1.12) |

|

| Grade | Low | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| High | 1.63 (1.42, 1.86) |

1.56 (1.35, 1.79) |

1.49 (1.29, 1.72) |

1.36 (1.17, 1.59) |

1.46 (1.38, 1.55) |

1.40 (1.32, 1.49) |

1.48 (1.40, 1.58) |

1.48 (1.39,1.57) |

|

| Histology | Adeno NOS | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mucinous | 1.32 (1.04, 1.67) |

1.30 (1.02, 1.66) |

1.11 (0.86, 1.43) |

1.06 (0.82, 1.37) |

0.98 (0.89, 1.09) |

0.93 (0.84, 1.03) |

0.98 (0.88, 1.08) |

0.93 (0.84,1.03) |

|

| Signet Cell | 2.48 (1.84, 3.35) |

2.05 (1.49, 2.82) |

2.16 (1.55, 2.99) |

1.90 (1.35, 2.68) |

1.80 (1.52, 2.14) |

1.51 (1.27, 1.80) |

1.41 (1.16, 1.72) |

1.22 (1.00,1.50) |

|

| CEA | Normal | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Elevated | 1.37 (1.15, 1.62) |

1.55 (1.30, 1.85) |

1.67 (1.38, 2.01) |

1.70 (1.41, 2.05) |

1.43 (1.34, 1.54) |

1.55 (1.45, 1.67) |

1.57 (1.45, 1.70) |

1.71 (1.58,1.85) |

|

Model 1: Univariate

Model 2: Covariates included age, race, colonic location, tumor grade, histologic type, and CEA

HR and 95% CI for age correspond to a 10 yr increment

Overall, young AA men experienced worse survival compared to EAs (log-rank p=0.006), with lower median survival (22 versus 25 months) and five-year survival probabilities (0.07 versus 0.18) (Table 2). Similar to women, young men of both races with proximal CRC had the lowest survival. In young men, the greatest difference in survival was observed with rectal cancer when comparing AAs to their EA counterparts (21 versus 26 months). Stratified Cox regression analysis revealed that AA men had a higher risk of mortality than EA men (HR= 1.25, 95% CI= 1.06 to 1.47) (Table 3), even after adjustment for clinical covariates (HR= 1.29, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.52).

50 years of age and older

Personal characteristics along with clinical and pathologic features assessed at diagnosis differed by race in cases of populations of 50 years of age and older (Table 1). Average age at diagnosis was 3 years earlier in AA men and 4 years earlier in AA women than their EA counterparts. Similar to observations observed in cases < 50 years, AA men and women were more likely to have proximal tumors and higher CEA positivity, but less likely to have high-grade lesions. Older AA women had a 5% higher prevalence of proximal tumors than EA women. However, this difference was appreciably lower compared to the 17% difference observed in the younger cohort.

Overall, median survival was slightly higher in older EA compared to AA cases (Table 2; Figure 1). Most of the racial difference in survival in cases over the age of 50 years was confined to men. For example, median survival did not differ by race in women over 50 (13 months in EAs versus 14 months in AAs). The 5-year survival probability was only slightly higher in older EA women relative to AA (0.10 versus 0.07). Furthermore, the risk of death did not differ significantly by race in older women (HR 1.03, 95% CI0.95 to 1.11) (Table 3). Adjustment for the multiple prognostic factors at diagnosis increased the risk by 6% (HR= 1.09, 95% CI= 1.01 to 1.18).

In contrast, median survival in older AA men was poorer than in EA (13 months versus 16 months). Likewise, the 5-year survival probability was lower in older AA men compared to EA men (0.07 versus 0.10). Based on stratified CPH regression models, the univariate analysis revealed a higher risk of death for older AA men compared to EA men (HR= 1.18, 95% CI = 1.09 to 1.27) (Table 3). Adjustment for covariates led to an increase in this racial difference (HR= 1.24, 95% CI=1.15 to 1.34).

Discussion

Our analysis using the population-based SEER registry data revealed poorer stage-specific survival in AA compared to EA, especially in less than 50 years of age. Overall we observed that 19% of AA cases were diagnosed with CRC under the age of 50 compared to 16% of EA. Significantly worse survival was observed for AA men in both younger and older age groups but the largest racial difference in survival occurred among AA women < 50 years who had 48% higher risk of death than younger EA women. In contrast, survival was poor for all women ≥ 50 years of age. The prevalence of several poor prognostic factors at diagnosis differed by race, age, and sex and appears to explain some of the reasons for differences in survival by race and age. AAs of all ages had a higher prevalence of proximal tumors, higher CEA level compared to EAs but a lower prevalence of high-grade tumors. Much of the difference in CRC survival by race in younger women appears to be due to the difference in the prevalence of the proximal neoplasia at diagnosis. In summary, our findings highlight the importance of considering patient’s age, sex, and colonic location on assessing the differences by race in stage IV CRC outcomes.

CRC is the second leading cause of cancer related death yet is one of the most preventable and treatable cancers when identified in the early stages with upwards of 90% survival at five years compared to less than 20% for stage IV cases. Despite recommendations by some physician organizations to begin screening earlier in AA (22, 23), others have argued that efforts should be directed toward increasing screening rates in those age 50 and over (24) because of the scarcities of resources and the much higher prevalence of disease in older patients. In the cases of this SEER cohort with stage IV CRC, approximately one-sixth of the cases were diagnosed before 50 years of age. Moreover, the average age of diagnosis in the younger cases was 45 years in AA men, 44 years in EA men and 44 years in both AA and EA women. From a public health perspective, screening younger aged AAs should be considered, regardless of the underlying etiology, given the poor survival and high prevalence of poor prognostic factors such proximal location.

Results of the present investigation mirror earlier reports showing survival differences were most pronounced by race in younger patients (5, 6, 25). In our earlier investigation, using South Carolina Central Cancer Registry data, we explored the associations between race, age and clinicopathologic features and stage IV CRC survival. In the multivariable proportional hazards regression, it was observed that AAs compared to EAs had a significantly higher risk of death after controlling for age, sex, year of diagnosis, and first-line chemotherapy use. As in the present analysis, we observed a significant interaction between race and age (p =0.04) on survival. Among AAs less than 50 years of age compared to EA, the adjusted HR was 1.34 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.71). The magnitude of the HR for cases < 50 years of age is similar to the adjusted HR found in the present study (HR 1.33 95% CI 1.18 to 1.49). The reason for the higher risk of death in younger cases is clearly complex, but at least partly due to the higher prevalence of proximal CRC in younger AAs compared to younger EA (Table 2). Similar to these results, many others (26–30) have reported a higher prevalence of proximal or advanced proximal neoplasia, especially microsatellite stable (MSS) CRC in AA compared to EA. Proximal colonic location outside of the context of MSI-High CRC is associated with greater mortality, especially among stage IV CRC patients (16, 31–33). Recent evidence has also documented a poorer response to treatment in patients with proximal CRC (20).

The racial difference in survival by race and sex differed in younger and older patients. In women, as reported above, there was marked difference in the prevalence of proximal CRC in women <50 (+17% AAs) but only a 5% difference by race among those ≥ 50 years. The reasons for the racial difference in survival among the younger women are not known but may reflect differences in the hormonal signatures by race. Younger EA women compared to AAs have higher estrogen levels (34–36), which could contribute to a lower prevalence of proximal neoplasia in younger women. Recently, a large prospective study reported a strong inverse association between endogenous estrogen levels and risk of CRC, especially for colon cancer compared to rectal (37). One possibility is that estrogen receptor expression loss results in more aggressive tumor behavior. In a murine model, the loss of estrogen receptor expression in the proximal colon leads to crypt fission and reduced wound healing (38), factors associated with increased tumor prevalence and growth. Moreover, poorer survival has been observed in younger aged AA women compared to EA women with breast cancer which may be explained by the higher proportion of poor prognostic ER− breast cancer tumors in AA (39). The poorer survival in younger aged AA women in the present study is similar to what we observed in our previous analysis (5).

Racial differences in initiation and adherence to standard treatment for CRC may contribute to the stage-specific survival differences. AA patients historically have been less likely to receive standard recommended therapy and refuse therapy at a higher rate (40). Although systemic therapy use is not available in SEER dataset, the available agents (capecitabine, 5FU, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, cetuximab) for the treatment of stage IV CRC remained consistent from 2004 to 2011, aside from the addition of panitumumab in 2006, and, more importantly, the restriction of EGFR-targeted therapies to KRAS wildtype tumors by 2008 (41). AA compared to EA are more likely to have KRAS mutant tumors (7, 30), and as a whole would be expected to derive less benefit from EGFR-targeted therapies. However, no notable differences in HRs for race were observed when we analyzed the time periods separately, i.e. in 2004–2007 vs. 2008–2011. AA compared to EA are less likely to undergo surgical interventions for non-metastatic colon and rectal cancer (40, 42, 43), raising the possibility that metastectomy rates may differ by race. To our knowledge, only one previous study has evaluated metastectomy rates by race and reported no differences (44). However, two large studies (44, 45) have found that AAs had significantly lower response rates to therapy, which could reduce the likelihood of undergoing resection.

We recognize strengths of our study, including the study of a large, racially diverse population of cases with advanced-stage colorectal cancer with careful characterization of demographic and pathologic characteristics as well as vital status. However, we also recognize its limitations. First, we had no data on patient-level factors (such as comorbid conditions or lifestyle and behaviors) or treatment regimen data, which could have confounded or modified the association between race and CRC survival. These results point to the need for detailed studies identifying risk factors for the poor prognostic signatures as well as patient-level, clinical, molecular, and treatment-related data to help advance understanding of the racial disparity in CRC survival.

In summary, using the large population based SEER dataset, we have shown that AAs with stage IV CRC have higher mortality than EAs, particularly in those < 50 years of age. These data suggest that CRC screening should have greater emphasis in younger AA cases and further raise the possibility that national guidelines for CRC screening should be modified especially for AA females.

Figure 2.

Survival distributions were analyzed, using survival probability in months from diagnosis, for (A) under 50 male, (B) under 50 female, (C) 50 & over male, (D) 50 & over female.

Clinical Practice Points.

Several previous investigations have detailed a racial disparity in colorectal cancer survival yet the reasons for this remain incompletely understood. The higher rates of death in AAs compared to EAs persist despite adjustment for common confounding variables such as sex, age, and socioeconomic status. Our results suggest that the racial difference in survival may be influenced by differences in prevalence of proximal and rectal CRC at diagnosis; survival among both AAs and EAs with proximal CRC in stage IV disease is poor. Future research is needed to understand why AAs develop proximal neoplasia at a younger age. There was a 17% difference in the prevalence of proximal CRCs in younger female AAs compared to EAs yet only a 5% difference by race among female cases ≥ 50 years. We also need to have a better understanding of how to improve treatment response in patients with stage IV proximal CRC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI via the Hollings Cancer Center NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA138313) and a K07 Career Development Award to Dr. Wallace (K07CA151864-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):104–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robbins AS, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality rates from 1985 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins AS, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality rates from 1985 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 30(4):401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soneji S, Iyer SS, Armstrong K, Asch DA. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality, 1960–2005. Am J Public Health. 100(10):1912–1916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace K, Hill EG, Lewin DN, Williamson G, Oppenheimer S, Ford ME, et al. Racial disparities in advanced-stage colorectal cancer survival. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(3):463–471. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andaya AA, Enewold L, Zahm SH, Shriver CD, Stojadinovic A, McGlynn KA, et al. Race and colon cancer survival in an equal-access health care system. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon HH, Shi Q, Alberts SR, Goldberg RM, Thibodeau SN, Sargent DJ, et al. Racial Differences in BRAF/KRAS Mutation Rates and Survival in Stage III Colon Cancer Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(10) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyerhardt JA, Mayer RJ. Systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(5):476–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shavers VL. Racial/ethnic variation in the anatomic subsite location of in situ and invasive cancers of the colon. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(7):733–748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton JG, Morris AM, Thornton JD, Flowers CR, McCashland TM. Racial variation in colorectal polyp and tumor location. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(7):723–728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, Eisen GM, Peters D, Morris CD. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic black and white patients. Jama. 2008;300(12):1417–1422. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma S, O'Keefe SJ. Environmental influences on the high mortality from colorectal cancer in African Americans. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(983):583–589. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.058958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashktorab H, Nouraie M, Hosseinkhah F, Lee E, Rotimi C, Smoot D. A 50-year review of colorectal cancer in African Americans: implications for prevention and treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(9):1985–1990. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0866-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace K, Grau MV, Ahnen D, Snover DC, Robertson DJ, Mahnke D, et al. The association of lifestyle and dietary factors with the risk for serrated polyps of the colorectum. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2310–2317. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meguid RA, Slidell MB, Wolfgang CL, Chang DC, Ahuja N. Is there a difference in survival between right- versus left-sided colon cancers? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2388–2394. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0015-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(19):1420–1425. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wray CM, Ziogas A, Hinojosa MW, Le H, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Tumor subsite location within the colon is prognostic for survival after colon cancer diagnosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(8):1359–1366. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a7b7de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalady MF, de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, Geisler DP, Dietz D, Lavery IC, et al. Predictive Factors of Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation for Rectal Cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(4):582–589. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b91e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boisen MK, Johansen JS, Dehlendorff C, Larsen JS, Osterlind K, Hansen J, et al. Primary tumor location and bevacizumab effectiveness in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2554–2559. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739–750. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH, Jr, Humphrey LL, Levine J, Sweet DE, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):378–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahnen DJ, Wade SW, Jones WF, Sifri R, Mendoza Silveiras J, Greenamyer J, et al. The increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: a call to action. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(2):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace K, Sterba KR, Gore E, Lewin DN, Ford ME, Thomas MB, et al. Prognostic factors in relation to racial disparity in advanced colorectal cancer survival. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12(4):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, de Boer J, Levin TR, et al. Variation of adenoma prevalence by age, sex, race, and colon location in a large population: implications for screening and quality programs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(2):172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lebwohl B, Capiak K, Neugut AI, Kastrinos F. Risk of colorectal adenomas and advanced neoplasia in Hispanic, black and white patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(12):1467–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieberman DA, Williams JL, Holub JL, Morris CD, Logan JR, Eisen GM, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and Sex Affect Risk for Polyps >9 mm in Average-Risk Individuals. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):351–358. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carethers JM, Murali B, Yang B, Doctolero RT, Tajima A, Basa R, et al. Influence of race on microsatellite instability and CD8+ T cell infiltration in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xicola RM, Gagnon M, Clark JR, Carroll T, Gao W, Fernandez C, et al. Excess of proximal microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer in African Americans from a multiethnic study. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(18):4962–4970. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benedix F, Kube R, Meyer F, Schmidt U, Gastinger I, Lippert H, et al. Comparison of 17,641 Patients With Right- and Left-Sided Colon Cancer: Differences in Epidemiology, Perioperative Course, Histology, and Survival. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2010;53(1):57–64. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c703a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suttie SA, Shaikh I, Mullen R, Amin AI, Daniel T, Yalamarthi S. Outcome of right- and left-sided colonic and rectal cancer following surgical resection. Colorectal Disease. 2011;13(8):884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wray CM, Ziogas A, Hinojosa MW, Le H, Stamos MJ, Zell JA. Tumor Subsite Location Within the Colon Is Prognostic for Survival After Colon Cancer Diagnosis. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2009;52(8):1359–1366. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a7b7de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim C, Golden SH, Mather KJ, Laughlin GA, Kong S, Nan B, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Sex Hormone Levels among Postmenopausal Women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(11):4051–4060. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamon-Fava S, Barnett Jb, Fau - Woods MN, Woods Mn, Fau - McCormack C, McCormack C, Fau - McNamara JR, McNamara Jr, Fau - Schaefer EJ, Schaefer Ej, Fau - Longcope C, et al. Differences in serum sex hormone and plasma lipid levels in Caucasian and African-American premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4516–4520. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randolph JF, Jr, Sowers M, Fau - Gold EB, Gold Eb, Fau - Mohr BA, Mohr Ba, Fau - Luborsky J, Luborsky J, Fau - Santoro N, Santoro N, Fau - McConnell DS, et al. Reproductive hormones in the early menopausal transition: relationship to ethnicity, body size, and menopausal status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4) doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy N, Strickler HD, Stanczyk FZ, Xue X, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Endogenous Sex Hormone Levels and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Postmenopausal Women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(10) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasson RM, Briggs A, Carothers AM, Davids JS, Wang J, Javid SH, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha or beta loss in the colon of Min/+ mice promotes crypt expansion and impairs TGFbeta and HNF3beta signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(1):96–102. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wray CJ, Phatak UR, Robinson EK, Wiatek RL, Rieber AG, Gonzalez A, et al. The Effect of Age on Race-Related Breast Cancer Survival Disparities. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;20(8):2541–2547. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2913-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esnaola NF, Gebregziabher M, Finney C, Ford ME. Underuse of Surgical Resection in Black Patients With Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer: Location, Location, Location. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(4):549–557. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b732a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Temple LK, Hsieh L, Wong WD, Saltz L, Schrag D. Use of surgery among elderly patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3475–3484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esnaola NF, Stewart AK, Feig BW, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Age-, race-, and ethnicity-related differences in the treatment of nonmetastatic rectal cancer: a patterns of care study from the national cancer data base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(11):3036–3047. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Green EM, McLeod HL, Goldberg RM. Racial differences in advanced colorectal cancer outcomes and pharmacogenetics: a subgroup analysis of a large randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(25):4109–4115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer and race: understanding the differences in outcomes between African Americans and whites. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(4):771–793. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]