Abstract

Purpose

To describe an atypical case of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR).

Methods

A 58-year-old man with longstanding, bilateral visual impairment was self-referred for a second opinion.

Results

Findings by direct ophthalmoscopy, optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) were suggestive of atypical, chronic CSCR. Treatment with oral anti-mineralocorticoids resulted in moderate improvement, and photodynamic therapy (PDT) had minimal effect.

Conclusion

Chronic CSCR may lack cardinal features of CSCR. Once retinal degenerative changes ensue, current treatments may not be effective in improving anatomical and visual outcomes in patients with chronic CSCR.

Keywords: Central serous chorioretinopathy, Cystoid macular edema, Eplerenone, Photodynamic therapy

Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) results in accumulation of subretinal fluid (SRF) secondary to hyperpermeability of the choroidal vessels and dysfunctional fluid management by the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE).1 Retinal and RPE atrophy may develop with chronic and relapsing episodes.2 In chronic cases, fundus autofluorescence (FAF) demonstrates fluid tracts with focal areas of hypoautofluorescence and hyperautofluorescent borders.3

CSCR is usually self-limited, but the need for rapid visual recovery may prompt treatment with photodynamic therapy (PDT).4, 5, 6, 7 Anti-mineralocorticoid therapies such as eplerenone,8, 9, 10 spironolactone,11, 12 or rifampin13, 14, 15 are also an alternative. Here we report a patient with atypical chronic CSCR and highlight the diagnostic challenges and response to treatments with medical management and PDT.

Case report

A 58-year-old man presented with a five- and 20-year history of visual impairment in the right and left eye, respectively. He reported having been previously diagnosed with macular degeneration and was seeking treatment at this juncture despite lack of subjective vision changes because his supervisor felt his poor vision was preventing him from carrying out his work duties. Medical history was significant for myopia and remote oral steroid use for unclear reasons. At presentation, vision was 20/70 and 20/400 in the right and left eye, respectively. His refraction was −3.25 + 0.50 × 10 in the right eye and −6.00 + 3.00 × 70 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed a normal anterior segment without evidence of keratic precipitates, cell, or flare to indicate current or previous episodes of inflammatory reactions. Dilated fundus examination demonstrated bilateral tilted discs with peripapillary atrophy, geographic atrophy with RPE changes more prominent in the left eye, and linear tracts of RPE atrophy in the near periphery of the inferior posterior pole (Fig. 1A and B).

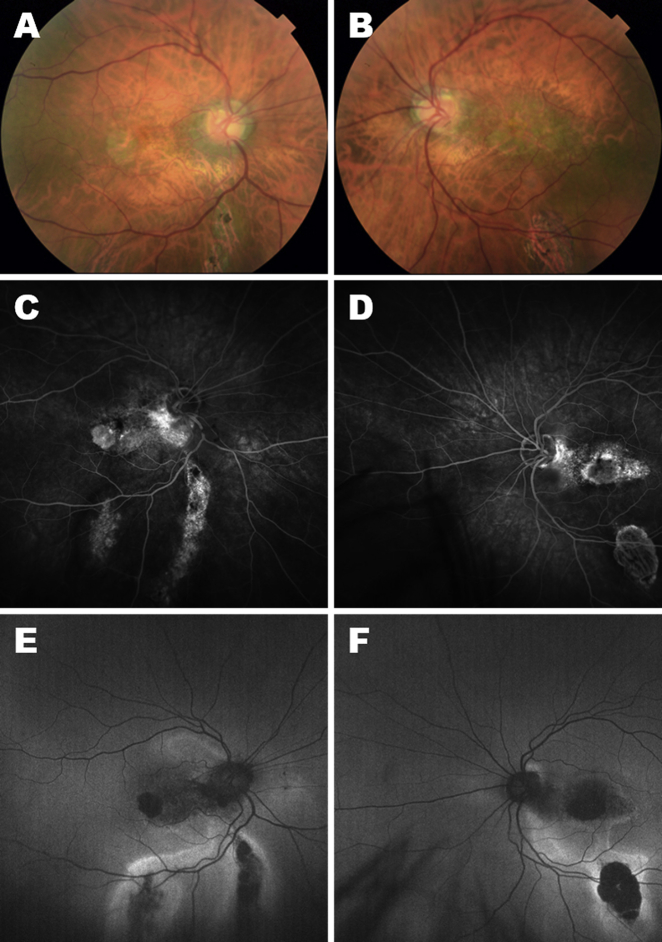

Fig. 1.

Color fundus photos of the right (A) and left (B) eye. Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right (C) and (D) left eye. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) of the right (E) and left (F) eye.

Fluorescein angiography (FA) demonstrated window defects, bilateral staining involving the fovea, temporal peripapillary region, and inferior retina, an absence of leakage, and no evidence of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) (Fig. 1C and D). FAF revealed bilateral areas of hypoautofluorescence in the macula with peripapillary extension and areas of hypoautofluorescence with surrounding hyperautofluorescence in linear and teardrop-shaped tracts peripherally (Fig. 1E and F). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) showed bilateral foveal atrophy, outer retinal loss with absence of the ellipsoid zone, and cystoid macular edema (CME) more severe in the left eye with central macular thicknesses (CMT) of 259 and 498 μm in the right and left eye, respectively. Notably, there was an absence of SRF, RPE detachment, or choroidal thickening (Fig. 2A and C). Chronic CSCR was diagnosed based on gravitational patterns of atrophy, better appreciated on FAF.

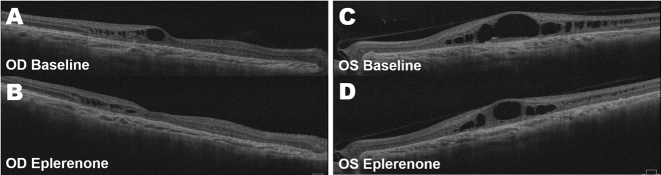

Fig. 2.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the right (A) and left (C) eye on initial presentation. One month following eplerenone treatment, the right (B) and left (D) eye demonstrated significant improvement in intraretinal fluid (IRF) with a minimal amount of cystoid edema in the right eye and more substantial in the left eye.

The patient was started on oral eplerenone 50 mg daily. After one month of treatment, visual acuity remained stable at 20/70 in the right eye but improved to 20/200 in the left eye. SD-OCT demonstrated bilateral improvement in intraretinal fluid (IRF) with CMTs of 219 and 461 μm in the right and left eye, respectively (Fig. 2B and D). After four months, eplerenone was discontinued as visual acuity, and IRF remained relatively stable apart from minimal monthly fluctuations. Subsequently, the patient underwent half fluence, guided PDT in the left eye. On follow-up two weeks, two months, and 14 months after the procedure, there was neither an improvement nor a decline in visual acuity, atrophic areas on FAF, or IRF on SD-OCT. CMT were 244 and 499 μm in the right and left eye, respectively.

Discussion

This case of chronic CSCR is unique as it is a case of CSCR with atypical features in a patient with high myopia and thin choroid. High myopia is considered a protective factor against CSCR, and CSCR is considered uncommon in myopic patients.16 Absence of choroidal thickening may be related to chronicity or have been mitigated by myopic degeneration. The patient's choroidal thickness (172 μm and 203 μm in the right and left eye, respectively) did not demonstrate substantial thickening when compared to values adjusted for age (275.52 ± 76 μm) or both refractive error and age (169.78 ± 45.3 μm and 158.02 ± 45.3 μm in the right and left eye, respectively).17, 18, 19 Furthermore, the predominant findings were CME on SD-OCT and staining on FA with a lack of characteristic CSCR findings such as leakage, SRF, RPE detachments, and choroidal thickening. FAF was critical for the diagnosis; hypoautofluorescent lesions with gravitational patterns and adjacent areas of hyperautofluorescent were very suggestive of chronic CSCR.

Treatment with oral eplerenone was initially effective but plateaued after one month. Half fluence PDT did not produce any additional effects. A possible etiology for the limited response to treatment may be secondary to the absence of leakage and lack of choroidal thickening. The presence of CME in the absence of leakage also suggests that retinal cystoid spaces may be the result of degeneration rather than active fluid movement.2 Such cystic changes are possibly prognostic signs for poor treatment response.

It is plausible that retinal degeneration which ensued from extended neurosensory detachment could cause permanent vision loss unresponsive to current treatment modalities. Early diagnosis of CSCR as well as appropriate and timely treatment are important in preventing degenerative changes and optimizing visual outcomes.

Footnotes

Financial and proprietary interest: The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the materials presented herein.

Peer review under responsibility of the Iranian Society of Ophthalmology.

References

- 1.Gemenetzi M., De Salvo G., Lotery A.J. Central serous chorioretinopathy: an update on pathogenesis and treatment. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(12):1743–1756. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iida T., Yannuzzi L.A., Spaide R.F., Borodoker N., Carvalho C a, Negrao S. Cystoid macular degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2003;23(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200302000-00001. 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson B., Noble J., Forooghian F., Meyerle C. Central serous chorioretinopathy: update on pathophysiology and treatment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(2):103–126. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia Parodi M., Da Pozzo S., Ravalico G. Photodynamic therapy in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2003;23(2):235–237. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200304000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim J.I., Glassman A.R., Aiello L.P. Collaborative retrospective macula society study of photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva R.M., Ruiz-Moreno J.M., Gomez-Ulla F. Photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a 4-year follow-up study. Retina. 2013;33(2):309–315. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182670fbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yannuzzi L.A., Slakter J.S., Gross N.E. Indocyanine green angiography-guided photodynamic therapy for treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a pilot study. Retina. 2003;32(Suppl 1):288–298. doi: 10.1097/iae.0b013e31823f99a9. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breukink M.B., den Hollander A.I., Keunen J.E.E., Boon C.J.F., Hoyng C.B. The use of eplerenone in therapy-resistant chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(6):e488–e490. doi: 10.1111/aos.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruszka A. Potential involvement of mineralocorticoid receptor activation in the pathogenesis of central serous chorioretinopathy: case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(10):1369–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bousquet E., Beydoun T., Zhao M., Hassan L., Offret O., Behar-Cohen F. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism in the treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a pilot study. Retina. 2013;33(10):2096–2102. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318297a07a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabrielian A., MacCumber M.W. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with the use of spironolactone, aldosterone receptor antagonist. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6(4):393–395. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182437db8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herold T.R., Prause K., Wolf A., Mayer W.J., Ulbig M.W. Spironolactone in the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy - a case series. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol = Albr Graefes Arch für Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(12):1985–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pouw A.E., Olmos de Koo L.C. Oral rifampin for central serous retinopathy: a strategic approach in three patients. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46(1):98–102. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20150101-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravage Z.B., Packo K.H., Creticos C.M., Merrill P.T. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy responsive to rifampin. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6(1):129–132. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182235561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinle N.C., Gupta N., Yuan A., Singh R.P. Oral rifampin utilisation for the treatment of chronic multifocal central serous retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(1):10–13. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manayath G.J., Arora S., Parikh H., Shah P.K., Tiwari S., Narendran V. Is myopia a protective factor against central serous chorioretinopathy? Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(2):266–270. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.02.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yzer S., Fung A.T., Barbazetto I., Yannuzzi L.A., Freund K.B. Central serous chorioretinopathy in myopic patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(10):1339–1340. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara T., Imamura Y., Margolis R., Slakter J.S., Spaide R.F. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the choroid in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(3):445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolis R., Spaide R.F. A pilot study of enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the choroid in normal eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(5):811–815. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]