Abstract

Seed composition is one of the most important determinants of the economic values in soybean. The quality and quantity of different seed components, such as oil, protein, and carbohydrates, are crucial ingredients in food, feed, and numerous industrial products. Soybean researchers have successfully developed and utilized a diverse set of molecular markers for seed trait improvement in soybean breeding programs. It is imperative to design and develop molecular assays that are accurate, robust, high-throughput, cost-effective, and available on a common genotyping platform. In the present study, we developed and validated KASP (Kompetitive allele-specific polymerase chain reaction) genotyping assays based on previously known functional mutant alleles for the seed composition traits, including fatty acids, oligosaccharides, trypsin inhibitor, and lipoxygenase. These assays were validated on mutant sources as well as mapping populations and precisely distinguish the homozygotes and heterozygotes of the mutant genes. With the obvious advantages, newly developed KASP assays in this study can substitute the genotyping assays that were previously developed for marker-assisted selection (MAS). The functional gene-based assay resource developed using common genotyping platform will be helpful to accelerate efforts to improve soybean seed composition traits.

1. Introduction

Soybean seed is an essential source of protein and edible oil for human diets and animal feed. Soybean seed contains about 40% protein and 21% oil on a dry matter basis and drives the economy of soybean industry. While seed oil and protein content are important, fatty acids (oil components) and amino acids (protein components) are desirable factors for long shelf life and nutrition [1]. Soybean oil typically contains high levels of linoleic and linolenic acids that lead to low oil stability and off-flavors with less functionality for industrial uses, limiting the commercial marketability of the soybean oil [2]. High oxidative stability is desirable for a longer shelf life of oil, which in turn depends on the presence of the monounsaturated fatty acid (oleic acid); thus, higher oleic acid and lower linolenic acid, without generating trans-fats, are desirable criteria [3, 4]. Another important component of soybean seeds is carbohydrates, of which concentration is essential for animal feed digestibility [5]. Soybean seeds contain about 15% carbohydrates that consist of sucrose (~6%), raffinose (~1%), and stachyose (~4%). Raffinose and stachyose accumulation is indigestible and causes flatulence in poultry, swine, and pets, thereby reducing the economic and dietary value of soybean seeds [6]. Similarly, lipoxygenase (Lpx) [7, 8] and Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (KTI) [9] are important components of soybean seed composition. Reduced content is preferred for reducing undesirable flavor and antinutritional properties. These traits are controlled by multiple homologous genes, which makes it more challenging for soybean lines with several beneficial seed traits.

Commodity soybean seed contains palmitic (11%), stearic (4%), oleic (23%), linoleic (54%), and linolenic acid (8%). Soybean oil with elevated oleic acid (>75%) is desirable for nutrition, flavor, and improvement of shelf life. Moreover, higher oleic acid content is desired in biodiesel production to improve the oxidative stability of oil while augmenting cold flow [10]. On the other hand, the higher concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (linolenic and linoleic) reduces the oxidative stability of the oil that decreases flavor and storage quality. Soybean oil used for cooking purposes is often partially hydrogenated, resulting in trans-fat in the oil, which is unhealthy for the heart. Several genetic studies have characterized genes controlling monounsaturated (oleic acid) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic and linolenic acid) in soybean [11–13]. During seed development stage, the two oleate desaturase genes, FAD2-1A (Glyma10g42470) and FAD2-1B (Glyma20g24530), and the three linoleate desaturase genes, FAD3A (Glyma14g37350), FAD3B (Glyma02g39230), and FAD3C (Glyma18g06950), are the major contributors controlling oleic and linolenic acid levels. The combination of mutant alleles of FAD2-1A and FAD2-1B produces up to 80% oleic acid in soybean seed [14]. Similarly, a combination of FAD3A, FAD3B, and FAD3C mutant alleles can produce ultralow (<1%) linolenic acid.

While high oleic and low linolenic acid content are of importance to the commodity soybean, the manipulation of raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) is also an important aspect to improving soybean seed components [15]. In soybean, raffinose and stachyose are indigestible components that are undesirable in diets of poultry and swine [16]. The key step in raffinose and stachyose biosynthesis is mediated by the enzyme raffinose synthase (RS). Kerr and Sebastian (2000) reported PI 200508, with reduced levels of RFOs and elevated levels of sucrose due to variation in RS gene (Glyma06g18890). Recently, Qiu et al. [17] reported a 33 bp deletion in the exon 4 of stachyose synthase gene (STS gene, Glyma19g40550) of PI 603176A having ultralow stachyose content (0.5%).

Soybean seed storage protein consists of approximately 6% proteinase inhibitors, Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (KTi, 21 kDa), and Bowman–Birk trypsin inhibitor (BBTi, 7-8 kDa), which also contributes to indigestibility [18]. Mutation in KTi gene (Glyma08g45530) prevents the accumulation of Kunitz trypsin inhibitor protein during seed development and improves tryptic activity [9].

In addition to undesirable traits mentioned above, the beany or grassy flavor of soybean seed products is a major factor that limits human consumption of soybean [19]. The grassy and beany flavor in soybean and other legumes seeds is due to the oxidation products resulting from seed lipoxygenase activity. Mature soybean seed consists of three distinct lipoxygenase isozymes, lipoxygenase 1 (Glyma13g42320), lipoxygenase 2 (Glyma13g42310), and lipoxygenase 3 (Glyma13g42330). Mutation in these genes leads to reduced lipoxygenase enzyme activity and results in better quality soybean meal [7, 8, 20].

In an effort to elevate oleic acid, soybean breeders are currently introgressing two mutant alleles of FAD2 and FAD3 genes into elite backgrounds to develop new soybean cultivars with elevated oleic and reduced linolenic acid (http://unitedsoybean.org/). To achieve this goal, a robust and high-throughput genotyping assay will play a vital role in marker-assisted selection (MAS) and marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC). Strongly associated functional markers improve selection of superior cultivars and reduce intensive phenotyping efforts [21–24]. For decades, different molecular marker technologies, such as randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), simple sequence repeat (SSR), and diversity array technology [24], have been widely used in molecular plant breeding. However, these marker technologies are low-throughput, labor-intensive, and time-consuming compared with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers [23–28]. SNP markers have gained the popularity due to their robustness, suitability of automation, and abundance in the genomes; therefore, they are widely used in genetic diversity analysis, evolutionary relationships, and association mapping [29].

High-throughput genotyping platforms, such as Illumina GoldenGate arrays, Illumina Infinium BeadChips, Genotyping-by-sequencing, and Fluidigm SNPTypes, have been used for SNP genotyping of mapping populations and diverse germplasm. For improving seed composition in soybean, SimpleProbe and Taqman detection assays have been developed to identify mutant alleles of those genes [7, 14, 30–34]. A number of molecular markers (simple sequence repeats (SSR), randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), sequence characterized amplified regions (SCAR), cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences (CAPS/dCAPS), and diversity array technology (DArT)) and genotyping assay have been used in molecular plant breeding over the last several decades [35, 36]. Although some of markers and genotyping platforms are useful for rapid genotyping and are codominant, they are not generally economical for carrying out large scale genotyping projects. For example, these assays may require additional restriction digestion steps followed by gel running [36]. Moreover, these assays may require comparatively higher quantity and quality of DNA, longer processing time, and additional optimization to obtain definite genotyping results [37, 38]. To choose a genotyping platform, several factors, such as accuracy, reproducibility, multiplexing, cost-effectiveness (cost per genotype and instrument running cost), and time required for optimization and assay-run, need to be considered. The KASP assays (KBioscience, Hoddesdon, UK) have emerged as novel cost-effective marker assays, especially for molecular breeding, which had many applications in several crop plants, including soybean [22, 23, 33, 34, 39–44]. Since the advent of KASP assays, it has been well adopted and employed in various crop breeding programs because of its advantages over other assays. These advantages include throughput, robustness, and cost-effectiveness coupled with the requirements of less DNA quality and concentration, easy sample preparation, and simple PCR running protocol. Thus, in view of the KASP assay advantages, the objective of the present study was to develop high-throughput, breeder-friendly, locus specific, and cost-effective KASP assays to detect SNP markers associated with the mutant alleles for soybean seed composition traits. The KASP assays validated in this article will be beneficial for germplasm characterization, allele mining, marker-assisted backcrossing, and marker-assisted recurrent selection [45] in soybean breeding programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.1.1. Fatty Acids

A set of populations obtained from biparental crosses was used for validation of oleic and linolenic acid assays (Supplementary Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6572969). In addition, leaf tissue and FTA cards (Whatman Inc., Clifton, NJ, USA) were (at V2 stage) collected to validate FAD2-1B (MU-HO-4) genotyping assay. FTA is a paper-based system designed to fix and store nucleic acids directly from fresh tissues pressed into the treated paper (Fehr and Caviness, 1997 [51]).

2.1.2. Carbohydrates

For raffinose synthase (MU-RS2-1 and MU-RS2-2) assays, mutant sources (PI 200508 and mutagenized line 397) and artificial heterozygotes were tested along with a wild-type genotype, cultivar Williams 82. For stachyose synthase assay (MU-STS-1), an F2 population was used for marker validation [17].

2.1.3. Trypsin Inhibitor and Lipoxygenase

An F2 population SP6A-209 X PI 542044 was used to test for a Kunitz trypsin inhibitor assay (MU-KTI-1). SP6A-209 was F5 line carrying sts mutant allele with low stachyose and PI 542044 was germplasm with null trypsin inhibitor (KTI). Due to the unavailability of a segregating population for lipoxygenase assays (MU-Lox-1, MU-Lox-2, and MU-Lox-3), the mutant sources PI 408251 [7], Jinpumkong-2 [8] and PI 205085, and PI 417458 [7] were grown in a greenhouse and tested, respectively, along with a nonmutant genotype, cultivar Williams 82 (Table 1).

Table 1.

A summary of mutant sources of SNP markers and KASP genotyping assays developed and validated in various genetic materials for different seed composition traits used in the present study.

| Trait | Marker | Assay ID | Gene | Position | Effect on trait | Donor checks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic acid | FAD2-1A_17D | MU-HO-1 | Glyma10g42470 | S117N | Improves oil shelf life | 17 D | [46] |

| FAD2-1A_A_Del | MU-HO-2 | ∗A544 | PI603452 | [47] | |||

| FAD2-1B_327 | MU-HO-3 | Glyma20G24530 | P137R | PI283327 | [32] | ||

| FAD2-1B_I143T | MU-HO-4 | I143T | PI578451 | [32] | |||

|

| |||||||

| Linolenic acid | FAD3A_Del | MU-LL-1 | Glyma14g37350 | 6.4 kb del. | Oxidative and flavor instability | IA3024 | [31] |

| FAD3A_Splice | MU-LL-2 | G810A | CX1512-44; SB-01 | [48] | |||

| FAD3B_Splice | MU-LL-3 | Glyma02g39230 | G462A | IA3024 | [49] | ||

| FAD3C_G128E | MU-LL-4 | Glyma18g06950 | G128E | CX1512-44; SB-01 | [48] | ||

| FAD3C_H304Y | MU-LL-5 | H304Y | A29, IA3024 | [49] | |||

|

| |||||||

| Kunitz trypsin inhibitor | KTI | MU-KTI-1 | Glyma08g45530 | Q120∗ | Antinutritional | PI 542044 | [9] |

|

| |||||||

| Stachyose synthase | STS | MU-STS-1 | Glyma19g40550 | 33 bp del. | Antinutritional | SP6A-209 | [17] |

|

| |||||||

| Raffinose synthase | RS2_W | MU-RS2-1 | Glyma06g18890 | ∗TGG991 | Antinutritional | PI 200508 | [50] |

| RS2_397 | MU-RS2-2 | T107I | Antinutritional | 397 | [46] | ||

|

| |||||||

| Lipoxygenase | Lox-1 | MU-Lox-1 | Glyma13g42320 | 74 bp del. | Beany flavor | PI 408251 | [7] |

| Lox-2 | MU-Lox-2 | Glyma13g42310 | H532Q | Beany flavor | Jinpumkong-2 | [8] | |

| Lox3_G_100 | MU-Lox-3 | Glyma15g03030 | ∗G100 | Beany flavor | PI 205085; PI 417458 |

[7] | |

∗: deletion.

Young leaf tissue of V1 soybean seedlings was collected and freeze-dried for genomic DNA extraction. The tissue was ground using GenoGrinder (SPEX CertiPrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) in a microcentrifuge tube at 1,600 rpm for 2 min. DNA extraction was then performed following a nonhazardous protocol as previously described by King et al. (2014).

2.2. KASP Assay Development

To develop KASP genotyping assays, sequence information based on published mutant genes and sources (Table 1) was used [7, 14, 17, 31, 32, 47]. The KASP genotyping assay is fluorescence (FRET) based assay and enables identification of biallelic SNPs and InDels. Two allele-specific forward primers along with tail sequences and one common reverse primer (Table 2) were synthesized by LGC Genomics (http://www.lgcgroup.com). The reaction mixture was prepared following the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications in number of cycles (KBioscience; http://www.lgcgroup.com/products/kasp-genotyping-chemistry/#.VsZK7PkrKM8). Briefly, KASP assays were run with 10 μL final reaction volume containing 5 μL KASP master mix, 0.14 μL primer mix, 2 μL of 10–20 ng/μL genomic DNA, and 2.86 μL of water. The following thermal cycling conditions were used: 15 min at 95°C, followed by 10 touchdown cycles of 20 s at 94°C and 1 min at 61–55°C (dropping 0.6°C per cycle), and then 26 cycles of 20 s at 94°C and 1 min at 55°C. For each assay 26 cycles were used excluding MU-HO-4 and MU-LL-1 which required additional 4 cycles (total 30 cycles). The fluorescent endpoint genotyping method was carried out using Roche LightCycler 480-II instrument (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA). In endpoint genotyping a signal is generated when dyes bound to allele-specific probes and depending upon hybridization (mismatch or perfect match) the corresponding fluorescent single can be measured (https://molecular.roche.com/systems/lightcycler-480-system/).

Table 2.

A list of SNP markers, designated ID, primers, and probes for KASP assays developed and validated in in this study.

| Marker | Fluorescent primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| FAD2-1A_17D (MU-HO-1) | FAM_primer | TCTCACTGGTGTGTGGGTGATTGCTCACGAGTGTGGTCACCATGCCTTCAG |

| HEX_primer | TCTCACTGGTGTGTGGGTGATTGCTCACGAGTGTGGTCACCATGCCTTCAA | |

| Reverse primer | CAAGTACCAATGGGTTGATGATGTTGTGGGTTTGACCCTTCACTCAACA | |

|

| ||

| FAD2-1A_452 (MU-HO-2) |

FAM_primer | TTTGTCCCAAAACCAAAATCCAAAGTTGCATGGTTTTCCAAGTACTTAAACAACCCTCTAGGAA |

| HEX_primer | TTTGTCCCAAAACCAAAATCCAAAGTTGCATGGTTTTCCAAGTACTTAAACAACCCTCTAGGA _∗ | |

| Reverse primer | GGGCTGTTTCTCTTCTCGTCACACTCACAATAGGGTGGCCTATGTATTTAGCCTTC | |

|

| ||

| FAD2-1B_327 (MU-HO-3) | FAM_primer | CCTTCAGCAAGTACCCATGGGTTGATGATGTTATGGGTTTGACCGTTCACTCAGCACTTTTAGTCCC |

| HEX_primer | CCTTCAGCAAGTACCCATGGGTTGATGATGTTATGGGTTTGACCGTTCACTCAGCACTTTTAGTCCG | |

| Reverse primer | TTATTTCTCATGGAAAAYAAGCCATCGCCGCCACCACTCCAACACGGGTTCCCTTGACCGTGATG | |

|

| ||

| FAD2-1B_I143T (MU-HO-4) | FAM_primer | TGGGTTGATGATGTTATGGGTTTGACCGTTCACTCAGCACTTTTAGTCCSTTATTTCTCATGGAAAAT |

| HEX_primer | TGGGTTGATGATGTTATGGGTTTGACCGTTCACTCAGCACTTTTAGTCCSTTATTTCTCATGGAAAAC | |

| Reverse primer | AAGCCATCGCCGCCACCACTCCAACACGGGTTCCCTTGACCGTGATGAAGTGTTTGTCC | |

|

| ||

| FAD3A_Del (MU-LL-1) |

FAM_primer | AATAAGAACTAAATTTAAAAGTGAAGTTGAAT |

| HEX_primer | AATAAGAACTAAATTTAAAAGTGAAGTTGAAC | |

| Reverse primer | GCAAGTTGTTCAGAAAACGTTAAAACTCC | |

|

| ||

| FAD3A_Splice (MU-LL-2) |

FAM_primer | CTGGACTTTGTCACATACTTGCATCACCATGGTCATCATCAGAAACTGCCTTGGTATCGCGGCAAGG |

| HEX_primer | CTGGACTTTGTCACATACTTGCATCACCATGGTCATCATCAGAAACTGCCTTGGTATCGCGGCAAGA | |

| Reverse primer | TAACAAAAATAAATAGAAAATAGTGAGTGAACACTTAAATGTTAGATACTACCTTCTTCTTCTTT | |

|

| ||

| FAD3B_Splice (MU-LL-3) | FAM_primer | GAATCTTTATGCTTCCTGAGGCTGTTCTTGAACATGGCTCTTTTTTATGTGTCATTATCTTAG |

| HEX_primer | GAATCTTTATGCTTCCTGAGGCTGTTCTTGAACATGGCTCTTTTTTATGTGTCATTATCTTAA | |

| Reverse primer | TTAACAGAGAAGATTTACAAGAATCTAGACAGCATGACAAGACTCATTAGATTCACTGT | |

|

| ||

| FAD3C_G128E (MU-LL-4) |

FAM_primer | CATGGAAGTTTTTCAAACAGTCCTTTGTTGAACAGCATTGTGGGCCACATCTTGCACTCTTCAATTCTTGTACCATACCATGG |

| HEX_primer | CATGGAAGTTTTTCAAACAGTCCTTTGTTGAACAGCATTGTGGGCCACATCTTGCACTCTTCAATTCTTGTACCATACCATGA | |

| Reverse primer | ATGGTCGGTTCCTTTTAGCAACTTTTCATGTTCACTTTGTCCTTAAATTTTTTTTTATGTTTGTT | |

|

| ||

| FAD3C_H304Y (MU-LL-5) |

FAM_primer | TAGATCGCGACTATGGTTGGATCAACAACATTCACCATGACATTGGCACCCATGTTATCCATC |

| HEX_primer | TAGATCGCGACTATGGTTGGATCAACAACATTCACCATGACATTGGCACCCATGTTATCCATT | |

| Reverse primer | ACCTTTTCCCTCAAATTCCACATTATCATTTAATCGAAGCGGTATTAATTCTCTATTTC | |

|

| ||

| KTI_2 (MU-KTI-1) |

FAM_primer | AACAAAGATGCAATGGATGGTTGGTTTAGACTTG |

| HEX_primer | AACAAAGATGCAATGGATGGTTGGTTTAGACTTT | |

| Reverse primer | AGAGNNNNNNNTTTCTGATGATGAATTCAATAACTAT | |

|

| ||

| STS_2 (MU-STS-1) |

FAM_primer | GAATTGGAGTGTGTTGAGAAGGGTGCAAAGGTTAAGGTTAAGGGTGATGGGAGATTCCTT_+ |

| HEX_primer | GAATTGGAGTGTGTTGAGAAGGGTGCAAAGGTTAAGGTTAAGGGTGATGGGAGATTCCTTGCTTACTCAAGTGAATCTCCAAAGAAGTTCCAAY | |

| Reverse primer | TGAATGGTTCTGATGTTGCTTTTGAGTGGCTCCCTGATGGAAAACTCACTCTCAACCTTGCTTGGATTGAAGAGAATGGCGGGGTT | |

|

| ||

| RS2_W (MU-RS2-1) |

FAM_primer | GGTATGGGTGCCTTTGTTAGGGACTTGAAGGAACAGTTTAGGAGCGTGGAGCAGGTGTATGTG_+ |

| HEX_primer | GGTATGGGTGCCTTTGTTAGGGACTTGAAGGAACAGTTTAGGAGCGTGGAGCAGGTGTATGTGTGG | |

| Reverse primer | CACGCGCTTTGTGGGTATTGGGGTGGGGTCAGACCCAAGGTTCCGGGCATGCCCCAGGCTAAGGTT | |

|

| ||

| RS2_397 (MU-RS2-2) |

FAM_primer | CTGGGGAAGCTCAGAGGAATAAAATTCATGAGCATATTCCGGTTTAAGGTGTGGTGGACCAC |

| HEX_primer | CTGGGGAAGCTCAGAGGAATAAAATTCATGAGCATATTCCGGTTTAAGGTGTGGTGGACCAT | |

| Reverse primer | TCACTGGGTCGGTAGCAACGGACACGAACTGGAGCACGAGACACAGATGATGCTTCTCGACA | |

|

| ||

| Lox-1 (MU-Lox-1) |

FAM_primer | CATGCGGCGATGGAGCCATTCGTCATAGCAACACACCGACATCTTAGCGTGCTTCACCCAATTTA_+ |

| HEX_primer | CATGCGGCGATGGAGCCATTCGTCATAGCAACACACCGACATCTTAGCGTGCTTCACCCAATTTACAAGCTTCTGACTCCTCACTATCGTAACAACATGAACATCAACGCACTTGCCAGGCAATCTCTAATTAATGCTA | |

| Reverse primer | ATGGCATAATAGAGACAACCTTTTTGCCCTCAAAGTATTCTGTGGAGATGTCTTCGGCGGTTT | |

|

| ||

| Lox-2 (MU-Lox-2) |

FAM_primer | CATCTATGATGTATGTTATGTCTCAATTTTATTTTATTTTTATTTTTTATTTTGTTCATAGGTTAAATACTCAT |

| HEX_primer | CATCTATGATGTATGTTATGTCTCAATTTTATTTTATTTTTATTTTTTATTTTGTTCATAGGTTAAATACTCAA | |

| Reverse primer | GCGGTGATTGAGCCATTCATCATAGCAACAAACCGACACCTTAGTGCTCTTCACCCAATTTATAAGCTTC | |

|

| ||

| Lox3_G_100 (MU-Lox-3) | FAM_primer | AGGGACAGTGGTGTTGATGCGCAAGAATGTGTTGGACGTGAATAGCGTAACCAGCGTTGGGG_+ |

| HEX_primer | AGGGACAGTGGTGTTGATGCGCAAGAATGTGTTGGACGTGAATAGCGTAACCAGCGTTGGGGG | |

| Reverse primer | AATTATTGGTCAAGGTCTCGACTTAGTTGGCTCAACACTCGATACTCTTACTGCCTT | |

_∗: HEX_primer and _+: FAM_primer.

3. Results and Discussion

Several breeding programs in the US are currently in the process of introgressing fatty acids and carbohydrates (CHO) mutant genes into soybean cultivars with elevated oleic and reduced linolenic acids along with modified CHO. Soybean varieties with desirable seed composition traits will help increase soybean demand and benefit the soybean industry. A robust and cost-effective genotyping assay is of prime importance to combine these desirable genes using MABC. In previous studies, the genetic basis of high oleic and low linolenic acid content has been identified in certain sources and functional SNP assays have also been developed [13, 30, 32, 48, 49, 52]. However, the existing SNP genotyping assays are not as breeder-friendly for applications in the soybean breeding programs with high-throughput settings. Recently, Shi et al. [33, 34] developed SNP assays for fatty acid mutants using different chemistry and suggested the advantage of those assays related to processing time and DNA quality [33, 34]. Previous assays for fatty acid mutants were developed using either SimpleProbe or TaqMan chemistry. As different genetic markers are frequently applied for germplasm or population screening, there is need for common genotyping platform. The combination of genotyping assays with different chemistry (e.g., SimpleProbe, TaqMan, or KASP) is being used in soybean breeding program; however utilization of different type assays in one breeding program may not be as efficient in terms of handling, data analysis, and variation in protocol. In this study, all the assays were developed using a common genotyping chemistry and platform, KASP technology, which could minimize common laboratory errors, such as handling different reaction mixtures, protocols for assays run, data analysis, and data export.

We have successfully developed and validated KASP assays to detect functional SNP or Indel markers for previously reported genes related to various seed composition traits. Sequence information of target genes and corresponding mutant sources are summarized in Table 1. The data obtained in the present study was compared with the previously reported SimpleProbe and Taqman assays (Supplementary Tables S2, S3, and S4). Initially, some of the KASP assays did not show a clear separation of heterozygote alleles from either mutant or wild-type alleles. Subsequently, this problem was overcome by optimization, in which additional numbers of thermal cycles were added.

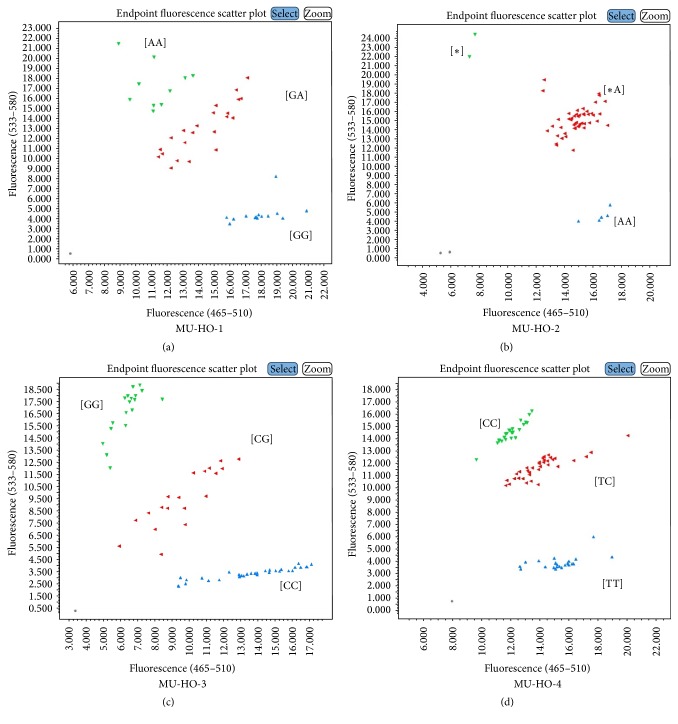

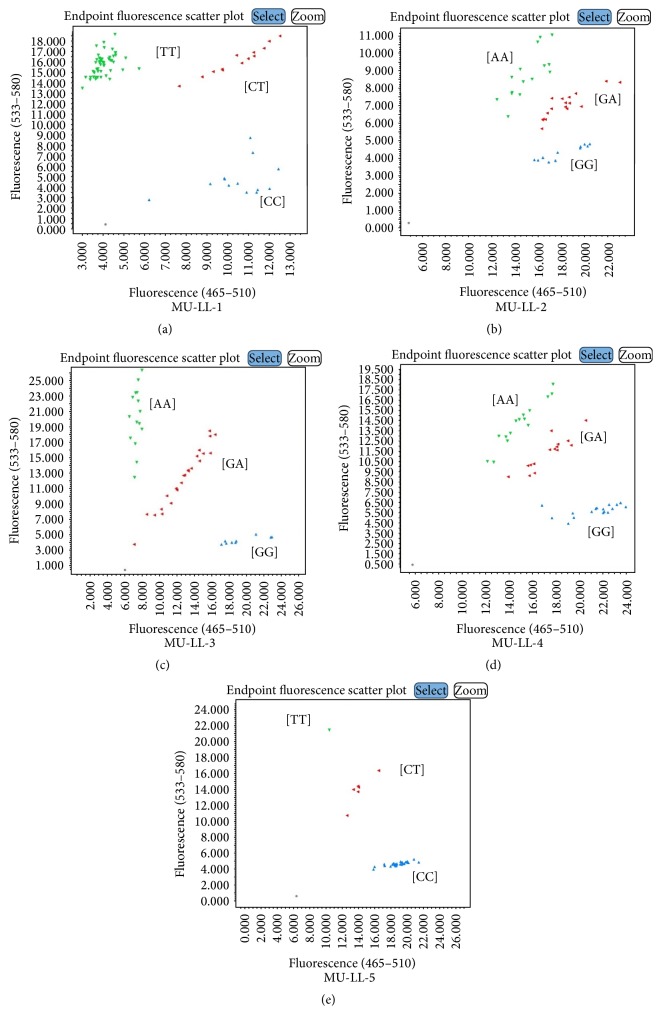

Among several genotyping assays tested, the assays of FAD2-1A gene for two mutant sources, 17D (MU-HO-1) and a deletion mutant, PI 603452 (MU-HO-2), were validated in segregating populations (Supplementary Table S2; Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Similarly, the genotyping assays developed to detect SNP markers of two mutants of FAD2-1B [PI 283327 (MU-HO-3) and PI 578451 (MU-HO-4)] were successfully validated (Figures 1(c) and 1(d)). To access the robustness of these genotyping assays, we used FTA cards (Whatman Inc., Clifton, NJ, USA) and tested with MU-HO-4 assays. The analysis showed a perfect correlation for the assays tested with genomic DNA (data not shown). The results were compared with previously reported molecular marker assays for validation [32, 46, 47]. For linolenic acid, MU-LL-1, MU-LL-2, MU-LL-3, MU-LL-4, and MU-LL-5 assays were developed and tested along with the SimpleProbe and the TaqMan assay methods in the segregating populations (Supplementary Table S3; Figure 2). A strong correlation and a clear separation of three genotypic clusters for MU-LL-1 (97.5%), MU-LL-2 (93%), MU-LL-3 (98%), MU-LL-4 (100%), and MU-LL-5 (95%) were observed. Recently, Pham et al. [31] characterized the fan1 locus in a soybean line A5 and developed a TaqMan assay for a complex insertion and deletion in the FAD3A gene. Using a PCR-based genomic strategy, they identified a 6.4 kbp deletion and 165 bp insertion in the FAD3A gene. We utilized the sequence information to design a forward, fluorescein amidite (FAM) labelled primer (specific to the 165 bp insertion) and hexachloro-fluorescein (HEX) labelled primers (specific to the 6.4 kbp deletion; Williams 82) along with a common reverse primer. A strong correlation (98%) with a previously designed Taq-man assay [31] was observed (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1.

Endpoint fluorescence genotyping plots for high oleic (HO) acid trait. (a) FAD2-1A_17D where [GG] is wild-type with normal oleic acid content and [AA] is mutant with elevated oleic acid content; (b) FAD2-1A_Del where [AA] is wild-type with normal oleic acid content and [∗] is mutant with elevated oleic acid content; (c) FAD2-1B_327 where [CC] is wild-type with normal oleic acid content and [GG] is mutant with elevated oleic acid content; (d) FAD2-1B_I143T where [TT] is wild-type with normal oleic acid content and [CC] is mutant with elevated oleic acid content.

Figure 2.

Endpoint fluorescence genotyping plots for trait for low linolenic (LL) acid trait. (a) FAD3A_Del where [TT] is wild-type with normal linolenic acid content and [CC] is mutant with reduced linolenic acid content; (b) FAD3A_Splice where [GG] is wild-type with normal linolenic acid content and [TT] is mutant with reduced linolenic acid content; (c) FAD3B_Splice where [GG] is wild-type with normal linolenic acid content and [AA] is mutant with reduced linolenic acid content; (d) FAD3C_G128E where [GG] is wild-type with normal linolenic acid content and [AA] is mutant with reduced linolenic acid content; (e) FAD3C_H304Y where [CC] is wild-type with normal linolenic acid content and [TT] is mutant with reduced linolenic acid content.

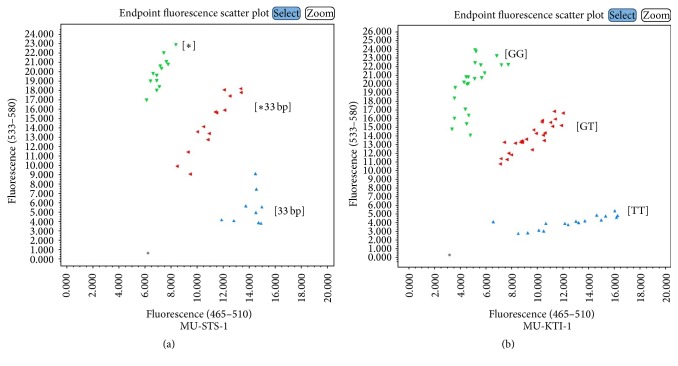

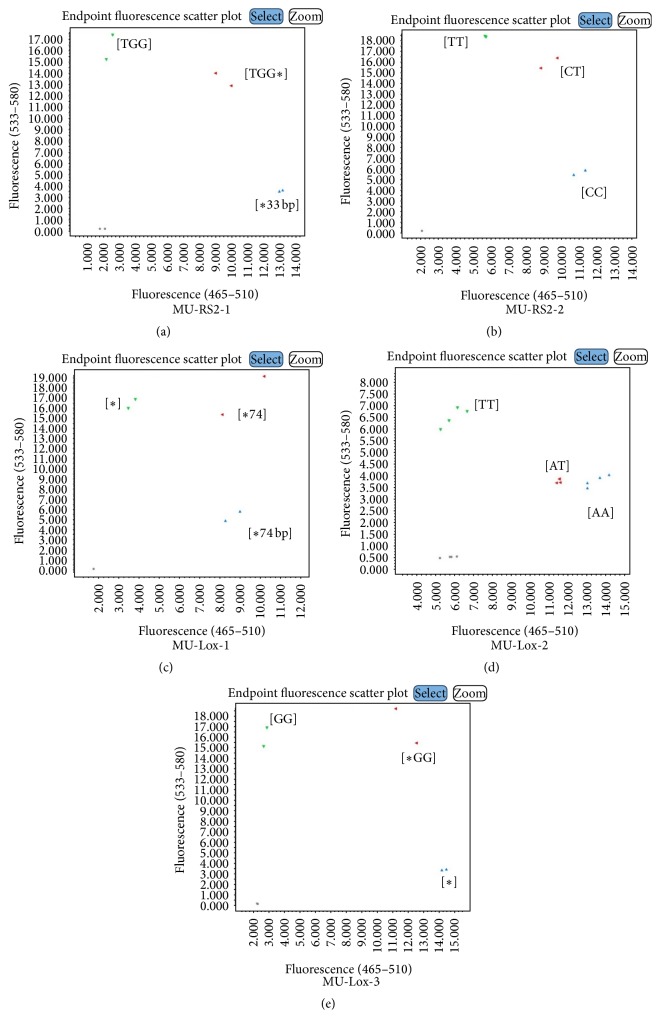

The KASP assays were also developed and validated for mutant genes conferring traits important for soybean meal digestibility, which included raffinose synthase (rs2), stachyose synthase (sts), and Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (kti). The MU-STS-1 and MU-KTI-1 assays were tested in a genetic mapping population and found to be in concordance with earlier reported molecular marker assays [17]. The MU-STS-1 assay showed a 78% of correlation with previously developed genotyping assay, while MU-KTI-1 showed 98.4% correlation (Supplementary Table S4, Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Due to the unavailability of mapping populations or diverse germplasm for MU-RS2-1, MU-RS2-2, and MU-Lox-1-3, these markers were tested on corresponding mutant and wild-type (Williams 82) sources. All assays accurately detected desired genotypes (Figures 4(a)–4(e)). We also tested several assays on artificial heterozygous genomic DNA, in which the DNA of mutant and wild-type (Williams 82) lines were mixed at equal concentrations of 10 ng/μL. This artificial heterozygote allele correctly designated the genotype and was clustered between mutant and wild-type alleles (Figures 4(a)–4(e)).

Figure 3.

Endpoint fluorescence genotyping plots for trait for (a) stachyose synthase (STS) where [∗] is mutant allele with reduced stachyose and [33 bp] is wild-type allele with normal stachyose concentration; (b) Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (KTI) where [GG] is wild-type allele with normal trypsin and [TT] is mutant allele with reduced trypsin content.

Figure 4.

Endpoint fluorescence genotyping plots for raffinose synthase (RS2) and lipoxygenase (Lox). (a) RS2_W where [TGG] is wild-type allele with normal raffinose and [∗3 bp] is mutant allele with reduced raffinose; (b) RS2_397 where [CC] is wild-type allele with normal raffinose and [TT] is mutant allele with reduced raffinose; (c) Lox-1 where [∗] is wild-type with normal lipoxygenase and [∗74] is mutant allele with reduced lipoxygenase; (d) Lox-2 where [TT] is wild-type allele and [AA] is mutant allele with reduced lipoxygenase; (e) Lox3_G_100 where [GG] is wild-type allele and [∗] is mutant allele with reduced lipoxygenase.

The validated KASP detection assays in our study will be beneficial for various practical applications, such as germplasm characterization, allele mining, and MAS in backcrossing and forward breeding programs. These SNP genotyping assays can be used for both routinely extracted genomic DNA and FTA cards (for DNA collection) to screen genetic and breeding materials at early growth stages (V1 or V2) (Fehr and Caviness, 1997). The DNA obtained from FTA card and assayed using KASP is a rapid and more economical screening compared to DNA extracted using other methods. The chemistry of KASP assays offered flexibility in designing and high locus specificity, which makes the assays accurate and robust. Unlike other PCR-based genotyping assays, KASP requires no labelling of the target-specific primer or probes, which provide cost advantage over other genotyping assays. The KASP assay is specific to the SNP or Indel markers to be targeted and consists of two competitive, allele-specific forward primers (labelled with fluorescent dye) and one common primer (http://www.lgcgroup.com/). In addition, the clustering of data points from the assay allows the genotyping results to be straightforward, which greatly benefits the SNP allele identification.

To estimate the economic profile, the costs of KASP assays were compared with SimpleProbe and Taqman assay (Supplementary Table S5). The comparison showed that total costs of the KASP assays were the most economical among the three tested assays (Supplementary Table S5). For instance, the costs of KASP assays were about 35% of those of TaqMan assays and about 70% of those of SimpleProbe assays. Moreover, if the KASP assay is optimized for the 5 μL of reaction volume, the cost of the assay is likely to be even more economical compared to other assays. The small reaction volume, simplicity of PCR implementation, and data acquisition will make the entire genotyping process affordable, fast, and accurate. Because of these advantages, KASP assays have been developed for various traits in soybean, such as frogeye leaf spot resistance [53], soybean cyst nematode resistance [22, 33, 34], and salinity tolerance [23].

In summary, the improvement of soybean seed composition traits is of tremendous interest to soybean growers because of its nutritional importance in food and feed as well as industrial applications. This study successfully developed robust and cost-effective KASP genotyping assays based on previously identified functional SNP marker information for six seed composition traits. It included high oleic, low linolenic acid, raffinose and stachyose synthase, Kunitz trypsin inhibitor, and lipoxygenase traits. It remarkably demonstrated robustness, high-throughput, and cost-effectiveness of KASP genotyping assays. Moreover, the accuracy of the assays was also validated in multiple soybean breeding populations and by data comparison with other genotyping assays; thus, the assays developed on a common genotyping platform can be adopted in soybean breeding programs, which facilitate the MAS of seed composition traits with greater efficiency and accuracy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: lists plant material used in this study and is self-explanatory.

Supplementary Tables 2–4: lists compares genotype call and it is explained in the main-text.

Supplementary Table 5: also explained in text.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this study provided by United Soybean Board and Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council. The authors also would like to thank Theresa A. Musket for editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Gunvant Patil and Juhi Chaudhary equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1.Bellaloui N., Bruns H. A., Abbas H. K., Mengistu A., Fisher D. K., Reddy K. N. Agricultural practices altered soybean seed protein, oil, fatty acids, sugars, and minerals in the Midsouth USA. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6, article 31 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warner K., Fehr W. Mid-oleic/ultra low linolenic acid soybean oil: a healthful new alternative to hydrogenated oil for frying. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2008;85(10):945–951. doi: 10.1007/s11746-008-1275-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemente T. E., Cahoon E. B. Soybean oil: genetic approaches for modification of functionality and total content. Plant Physiology. 2009;151(3):1030–1040. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.146282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.-D., Bilyeu K. D., Pantalone V. R., Gillen A. M., So Y.-S., Grover Shannon J. Environmental stability of oleic acid concentration in seed oil for soybean lines with FAD2-1A and FAD2-1B mutant genes. Crop Science. 2012;52(3):1290–1297. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2011.07.0345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerma H. R., Specht J. E., Wilson R. F. Soybeans: Improvement, Production, and Uses. American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America; 2004. Seed Composition. (Agronomy Monograph). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagely K. B., Palmquist D., Bilyeu K. D. Classification of distinct seed carbohydrate profiles in soybean. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61(5):1105–1111. doi: 10.1021/jf303985q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenis J. M., Gillman J. D., Lee J. D., Shannon G., Bilyeu K. D. Soybean seed lipoxygenase genes: molecular characterization and development of molecular marker assays. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2010;120(6):1139–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin J. H., Van K., Kim K. D., Lee Y.-H., Jun T.-H., Lee S.-H. Molecular sequence variations of the lipoxygenase-2 gene in soybean. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2012;124(4):613–622. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jofuku K. D., Schipper R. D., Goldberg R. B. A frameshift mutation prevents Kunitz trypsin inhibitor mRNA accumulation in soybean embryos. The Plant Cell. 1989;1(4):427–435. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graef G., LaVallee B. J., Tenopir P., et al. A high-oleic-acid and low-palmitic-acid soybean: agronomic performance and evaluation as a feedstock for biodiesel. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2009;7(5):411–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilyeu K. D., Palavalli L., Sleper D. A., Beuselinck P. R. Three microsomal omega-3 fatty-acid desaturase genes contribute to soybean linolenic acid levels. Crop Science. 2003;43(5):1833–1838. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2003.1833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heppard E. P., Kinney A. J., Stecca K. L., Miao G. H. Developmental and growth temperature regulation of two different microsomal ω-6 desaturase genes in soybeans. Plant Physiology. 1996;110(1):311–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlueter J. A., Vasylenko-Sanders I. F., Deshpande S., et al. The FAD2 gene family of soybean: insights into the structural and functional divergence of a paleopolyploid genome. Crop Science. 2007;47(1):14–26. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2006.06.0382tpg. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham A.-T., Shannon J. G., Bilyeu K. D. Combinations of mutant FAD2 and FAD3 genes to produce high oleic acid and low linolenic acid soybean oil. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2012;125(3):503–515. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minorsky P. V. Raffinose oligosaccharides. Plant Physiology. 2003;131(3):1159–1160. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dierking E. C., Bilyeu K. D. Raffinose and stachyose metabolism are not required for efficient soybean seed germination. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2009;166(12):1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu D., Vuong T., Valliyodan B., et al. Identification and characterization of a stachyose synthase gene controlling reduced stachyose content in soybean. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2015;128(11):2167–2176. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2575-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K.-J., Yamashita T., Watanabe M., Takahata Y. Genetic characterization of a novel Tib-derived variant of soybean Kunitz trypsin inhibitor detected in wild soybean (Glycine soja) Genome. 2004;47(1):9–14. doi: 10.1139/g03-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rackis J. J., Sessa D. J., Honig D. H. Flavor problems of vegetable food proteins. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 1979;56(3):262–271. doi: 10.1007/BF02671470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang W. H., Takano T., Shibata D., Kitamura K., Takeda G. Molecular basis of a null mutation in soybean lipoxygenase 2: substitution of glutamine for an iron-ligand histidine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(13):5828–5832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asekova S., Kulkarni K. P., Patil G., et al. Genetic analysis of shoot fresh weight in a cross of wild (G. soja) and cultivated (G. max) soybean. Molecular Breeding. 2016;36(7, article 103) doi: 10.1007/s11032-016-0530-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadam S., Vuong T. D., Qiu D., et al. Genomic-assisted phylogenetic analysis and marker development for next generation soybean cyst nematode resistance breeding. Plant Science. 2015;242:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patil G., Do T., Vuong T. D., et al. Genomic-assisted haplotype analysis and the development of high-throughput SNP markers for salinity tolerance in soybean. Scientific Reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep19199.19199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varshney R. K., Kudapa H., Roorkiwal M., et al. Advances in genetics and molecular breeding of three legume crops of semi-arid tropics using next-generation sequencing and high-throughput genotyping technologies. Journal of Biosciences. 2012;37(5):811–820. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhary J., Patil G. B., Sonah H., et al. Expanding omics resources for improvement of soybean seed composition traits. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6, article 1021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasu S. Search for and Analysis of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in Rice (Oryza sativa, Oryza rufipogon) and Establishment of SNP Markers. DNA Research. 2002;9(5):163–171. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patil G. Identification of sequence variants in candidate genes for Oil content using whole genome Re-sequencing of soybean germplasm. Plant and Animal Genome. PAG-2014. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rafalski A. Applications of single nucleotide polymorphisms in crop genetics. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2002;5(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valliyodan B., Dan Q., Patil G. Landscape of genomic diversity and trait discovery in soybean. Scientific Reports. 2016;6, article 23598 doi: 10.1038/srep23598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chappell A. S., Bilyeu K. D. A GmFAD3A mutation in the low linolenic acid soybean mutant C1640. Plant Breeding. 2006;125(5):535–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01271.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pham A.-T., Bilyeu K., Chen P., Boerma H. R., Li Z. Characterization of the fan1 locus in soybean line A5 and development of molecular assays for high-throughput genotyping of FAD3 genes. Molecular Breeding. 2014;33(4):895–907. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-0003-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pham A. T., Lee J. D., Shannon J. G., Bilyeu K. D. Mutant alleles of FAD2-1A and FAD2-1B combine to produce soybeans with the high oleic acid seed oil trait. BMC Plant Biology. 2010;19:p. 195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Z., Bachleda N., Pham A. T., et al. High-throughput and functional SNP detection assays for oleic and linolenic acids in soybean. Molecular Breeding. 2015;35(8, article 176) doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0368-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Z., Liu S., Noe J., Arelli P., Meksem K., Li Z. SNP identification and marker assay development for high-throughput selection of soybean cyst nematode resistance. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1, article 314) doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1531-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lestari P., Koh H. J. Development of new CAPS/dCAPS and SNAP markers for rice eating quality. HAYATI Journal of Biosciences. 2013;20(1):15–23. doi: 10.4308/hjb.20.1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh B., Singh A. Marker-Assisted Plant Breeding: Principles and Practices. New Delhi, India: Springer; 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chantarangsu S., Cressey T., Mahasirimongkol S., et al. Comparison of the TaqMan and LightCycler systems in evaluation of CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism. Molecular and Cellular Probes. 2007;21(5-6):408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houghton S. G., Cockerill F. R., III Real-time PCR: overview and applications. Surgery. 2006;139(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holdsworth W. L., Mazourek M. Development of user-friendly markers for the pvr1 and Bs3 disease resistance genes in pepper. Molecular Breeding. 2015;35(1, article 28) doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0260-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pariasca-Tanaka J., Lorieux M., He C., McCouch S., Thomson M. J., Wissuwa M. Development of a SNP genotyping panel for detecting polymorphisms in Oryza glaberrima/O. sativa interspecific crosses. Euphytica. 2015;201(1):67–78. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1183-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramirez-Gonzalez R. H., Segovia V., Bird N., et al. RNA-Seq bulked segregant analysis enables the identification of high-resolution genetic markers for breeding in hexaploid wheat. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2015;13(5):613–624. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosso M. L., Burleson S. A., Maupin L. M., Rainey K. M. Development of breeder-friendly markers for selection of MIPS1 mutations in soybean. Molecular Breeding. 2011;28(1):127–132. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9573-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semagn K., Babu R., Hearne S., Olsen M. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP): overview of the technology and its application in crop improvement. Molecular Breeding. 2014;33(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9917-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan J., Wen Z., Gu C., Wang D. Introduction of high throughput and cost effective SNP geno—typing platforms in soybean. Plant Genetics, Genomics, and Biotechnology. 2014;2(1):90–94. doi: 10.5147/pggb.2014.0144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milne I., Shaw P., Stephen G., et al. Flapjack-graphical genotype visualization. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(24):3133–3134. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dierking E. C., Bilyeu K. D. New sources of soybean seed meal and oil composition traits identified through TILLING. BMC Plant Biology. 2009;9, article 89 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pham A.-T., Lee J.-D., Shannon J. G., Bilyeu K. D. A novel FAD2-1 A allele in a soybean plant introduction offers an alternate means to produce soybean seed oil with 85% oleic acid content. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2011;123(5):793–802. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bilyeu K., Palavalli L., Sleper D., Beuselinck P. Mutations in soybean microsomal omega-3 fatty acid desaturase genes reduce linolenic acid concentration in soybean seeds. Crop Science. 2005;45(5):1830–1836. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2004.0632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bilyeu K., Palavalli L., Sleper D. A., Beuselinck P. Molecular genetic resources for development of 1% linolenic acid soybeans. Crop Science. 2006;46(5):1913–1918. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.11-0426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dierking E. C., Bilyeu K. D. Association of a soybean raffinose synthase gene with low raffinose and stachyose seed phenotype. The Plant Genome Journal. 2008;1(2):135–145. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2008.06.0321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ndunguru J., Taylor N. J., Yadav J., et al. Application of FTA technology for sampling, recovery and molecular characterization of viral pathogens and virus-derived transgenes from plant tissues. Virology Journal. 2005;2(1, article 45) doi: 10.1186/1743-422x-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang G., Novitzky W. P., Carol Griffin H., Huber S. C., Dewey R. E. Oleate desaturase enzymes of soybean: evidence of regulation through differential stability and phosphorylation. Plant Journal. 2005;44(3):433–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pham A.-T., Harris D. K., Buck J., et al. Fine mapping and characterization of candidate genes that control resistance to Cercospora sojina K. Hara in two soybean germplasm accessions. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126753.e0126753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: lists plant material used in this study and is self-explanatory.

Supplementary Tables 2–4: lists compares genotype call and it is explained in the main-text.

Supplementary Table 5: also explained in text.