Abstract

Background

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is a pathogen classified into two biovars: C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis, the etiologic agent of caseous lymphadenitis and C. pseudotuberculosis biovar equi, which causes ulcerative lymphangitis. The available whole genome sequences of different C. pseudotuberculosis strains have enabled identify difference of genes related both virulence and physiology of each biovar. To evaluate be this difference could reflect at proteomic level and to better understand the shared factors and the exclusive ones of biovar ovis and biovar equi strains, we applied the label-free quantitative proteomic to characterize the proteome of the strains: 1002_ovis and 258_equi, isolated from goat (Brazil) and equine (Belgium), respectively.

Results

From this analysis, we characterized a total of 1230 proteins in 1002_ovis and 1220 in 258_equi with high confidence. Moreover, the core-proteome between 1002_ovis and 258_equi obtained here is composed of 1122 proteins involved in different cellular processes, which could be necessary for the free living of C. pseudotuberculosis. In addition, 120 proteins from this core-proteome presented change in abundant with statistically significant differences. Considering the exclusive proteome, we detected strain-specific proteins to each strain. When correlated, the exclusive proteome of each strain and proteome with change in abundant, the proteomic differences, between the 1002_ovis and 258_equi, this related to proteins involved in cellular metabolism, information storage and processing, cellular processes and signaling.

Conclusions

This study reports the first comparative proteomic study of the biovars ovis and equi of C. pseudotuberculosis. The results generated in this study provide information about factors which can contribute to understanding both the physiology and the virulence of this pathogen.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3835-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is a Gram-positive facultative intracellular pathogen of the Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, and Rhodococcus (CMNR) group. The CMNR group of pathogens has high G + C content in their genomes and shows a specific cell wall organization composed of peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan, and mycolic acids [1]. C. pseudotuberculosis is subdivided into two biovars: (i) C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis (nitrate negative) which is the etiologic agent of caseous lymphadenitis in small ruminants [2] and mastitis in dairy cattle [3] and (ii) C. pseudotuberculosis biovar equi (nitrate positive) that causes ulcerative lymphangitis and abscesses in internal organs of equines [4] and oedematous skin disease in buffalos [5]. C. pseudotuberculosis infection is reported worldwide and causes significant economic losses by affecting wool, meat, and milk production [6–9].

Various studies at genome level have been carried out by our research group in order to explore the molecular basis of specific and shared factors among different strains of C. pseudotuberculosis that could contribute to such biovar specific pathogenicity. Our studies on whole-genome sequencing and analysis of several C. pseudotuberculosis strains belonging to biovar ovis and equi, isolated from different hosts showed an average genome size of approximately 2,3 Mb, a core-genome having approximately 1504 genes across several C. pseudotuberculosis species, and accessory genomes of biovar equi and ovis composed of 95 and 314 genes, respectively [10–12]. According with pan-genome analysis, C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis presented a more clonal-like behavior, than the C. pseudotuberculosis biovar equi. In addition, in this in silico study was observed a variability most interesting related to pilus genes, where biovar ovis strain presented high similarity, while, biovar equi strains have a great variability, suggesting that this variability could influence in the adhesion and invasion cellular of each biovar [10].

Apart from the structural genome informatics studies of C. pseudotuberculosis, some proteomic studies were conducted to explore the functional genome of this pathogen [13–19]. However, all these proteomic studies were performed using only strains belonging to biovar ovis. Until the present time, no proteomic studies were performed between biovar equi strains or between biovar ovis and biovar equi strains. Therefore, to provide insights on shared and exclusive proteins among biovar ovis and biovar equi strains and to complement the previous studies on functional and structural genomics of C. pseudotuberculosis biovars, using LC-MSE approach [13, 18] this study reports for the first time a comparative proteomic analysis of two C. pseudotuberculosis strains, 1002_ovis and 258_equi, isolated from caprine (Brazil) and equine (Belgium), respectively. Our proteomic dataset promoted the validations of previous work in silico of C. pseudotuberculosis; in addition, the qualitative and quantitative differences in the proteins identified in this present work have potential to help understand the factors that might contribute for pathogenic process of biovar ovis and equi strains.

Methods

Bacterial strain and growth condition

C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis 1002, isolated from a goat in Brazil, and C. pseudotuberculosis biovar equi 258, isolated from a horse in Belgium, were maintained in brain–heart infusion broth or agar (1.5%) (BHI-HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India) at 37 °C. For proteomic analysis, overnight cultures (three biological replicate to each strain) in BHI were inoculated with a 1:100 dilution in fresh BHI at 37 °C and cells were harvested during the exponential growth at DO600 = 0.8 (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Protein extraction and preparation of whole bacterial lysates for LC-MS/MS

After bacterial growth, the protein extraction was performed according to Silva et al. [18]. The cultures were centrifuged at 4000 x g at 4 °C for 20 min. The cell pellets were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer (7 M Urea, 2 M Thiourea, CHAPS 4% and 1 M DTT) and 10 μL of Protease Inhibitor Mix (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) was added. The cells were broken by sonication at 5 × 1 min cycles on ice and the lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, samples were concentrated and lysis buffer was replaced by 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at pH 8.0 using a 10 kDa ultra-filtration device (Millipore, Ireland). All centrifugation steps were performed at room temperature. Finally the protein concentration was determined by Bradford method [20]. A total of 50 μg proteins from each biological replicate of 1002_ovis and 258_equi were denatured by using RapiGEST SF [(0.1%) (Waters, Milford, CA, USA)] at 60 °C for 15 min, reduced with DTT [(10 mM) (GE Healthcare)], and alkylated with iodoacetamide [(10 mM) (GE Healthcare)]. For enzymatic digestion, trypsin [(0.5 μg/μL) (Promega, Sequencing Grade Modified Trypsin, Madison, WI, USA)] was added and placed in a thermomixer at 37 °C overnight. The digestion process was stopped by the addition of 10 μL of 5% TFA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and glycogen phosphorilase (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the digests to give 20 fmol.uL−1 as an internal standard for scouting normalization prior to each replicate injection into label-free quantitation [21].

LC-HDMSE analysis and data processing

Qualitative and quantitative analysis were performed using 2D RPxRP (two-dimensional reversed phase) nanoUPLC-MS (Nano Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry) approach with multiplexed Nano Electrospray High Definition Mass Spectrometry (nanoESI-HDMSE). To ensure that all samples were injected with the same amount into the columns and to ensure standardized molar values across all conditions, stoichiometric measurements based on scouting runs of the integrated total ion account (TIC) were performed prior to analysis. The experiments were conducted using both a 1 h reversed phase gradient from 7% to 40% (v/v) acetonitrile (0.1% v/v formic acid) and a 500 nL.min−1 on a 2D nanoACQUITY UPLC technology system [22]. A nanoACQUITY UPLC HSS (High Strength Silica) T3 1.8 μm, 75 μm × 15 cm column (pH 3) was used in conjunction with a reverse phase (RP) XBridge BEH130 C18 5 μm 300 μm × 50 mm nanoflow column (pH 10). Typical on-column sample loads were 250 ng of total protein digests for each 5 fractions (250 ng/fraction/load). For all measurements, the mass spectrometer was operated in the resolution mode with a typical m/z resolving power of at least 35,000 FMHW and an ion mobility cell filled with nitrogen gas and a cross-section resolving power at least 40 Ω/ΔΩ. All analyses were performed using nano-electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode nanoESI (+) and a NanoLockSpray (Waters, Manchester, UK) ionization source.

The lock mass channel was sampled every 30 s. The mass spectrometer was calibrated with a MS/MS spectrum of [Glu1]-Fibrinopeptide B human (Glu-Fib) solution (100 fmol.uL−1) delivered through the reference sprayer of the NanoLockSpray source.The doubly- charged ion ([M + 2H]2+ = 785.8426) was used for initial single-point calibration and MS/MS fragment ions of Glu-Fib were used to obtain the final instrument calibration. Multiplexed data-independent (DIA) scanning with added specificity and selectivity of a non-linear ‘T-wave’ ion mobility (HDMSE) experiments were performed with a Synapt G2-S HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters), which was automatically planned to switch between standard MS (3 eV) and elevated collision energies HDMSE (19–45 eV) applied to the transfer ‘T-wave’ CID (collision-induced dissociation) cell with argon gas. The trap collision cell was adjusted for 1 eV, using a mili-seconds scan time previously adjusted based on the linear velocity of the chromatography peak delivered through nanoACQUITY UPLC to get a minimum of 20 scan points for each single peak, both in low energy and at high-energy transmission at an orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight (oa-TOF) from m/z 50 to 2000. The RF offset (MS profile) was adjusted is such a way that the nanoUPLC-HDMSE data are effectively acquired from m/z 400 to 2000, which ensured that any masses observed in the high energy spectra with less than m/z 400 arise from dissociations in the collision cell.

Database searching and quantification

Following the identification of proteins, the quantitative data were packaged using dedicated algorithms [23, 24] and searching against a database with default parameters to account for ions [25]. The databases used were reversed “on-the fly” during the database queries and appended to the original database to assess the false positive rate (FDR) during identification. For proper spectra processing and database searching conditions, the Protein Lynx Global Server v.2.5.2 (PLGS) with IdentityE and ExpressionE informatics v.2.5.2 (Waters) were used. UniProtKB (release 2013_01) with manually reviewed annotations was used, and the search conditions were based on taxonomy (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis). We have utilized a database from genome annotation of 1002_ovis CP001809.2 version and 258_equi CP003540.2 version. These databases were randomized within PLGS v.2.5.2 for generate a concatenated database from both genomes. Thus, the measured MS/MS spectra from proteomic datasets of 1002_ovis and 258_equi were searched against this concatenated database. The maximum allowed missed cleavages by trypsin were up to one, and variable modifications by carbamidomethyl (C), acetyl N-terminal, phosphoryl (STY) and oxidation (M) were allowed and peptide mass tolerance value of 10 ppm was used [26]. Peptides as source fragments, peptides with a charge state of at least [M + 2H]2+ and the absence of decoys were the factors we considered to increase the data quality. The collected proteins were organized by the PLGS ExpressionE tool algorithm into a statistically significant list that corresponded to higher or lower regulation ratios among the different groups. For protein quantitation, the PLGS v2.5.2 software was used with the IdentityE algorithm using the Hi3 methodology. The search threshold to accept each spectrum was the default value in the program with a false discovery rate value of 4%. The quantitative values were averaged over all samples, and the standard deviations at p < 0.05 were determined using the Expression software. Only proteins with a differential expression log2 ratio between the two conditions greater than or equal to 1.2 were considered [26].

Bioinformatics analysis

The identified proteins in 1002_ovis and 258_equi were subjected to the bioinformatics analysis using the various prediction tools. SurfG+ v1.0 [27] was used to predict sub-cellular localization, SignalP 4.1.0 server [28] to predict the presence of N-terminal signal peptides for secretory proteins, SecretomeP 2.0 server [29] to identify exported proteins from non-classical systems (positive prediction score greater than to 0.5), LipoP server [30] to determine lipoproteins, Blast2GO [31] and COG database [32] were used for functional annotations. The protein-protein interaction network was generated using Cytoscape version 2.8.3 [33] with a spring-embedded layout.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the proteome of C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis and equi

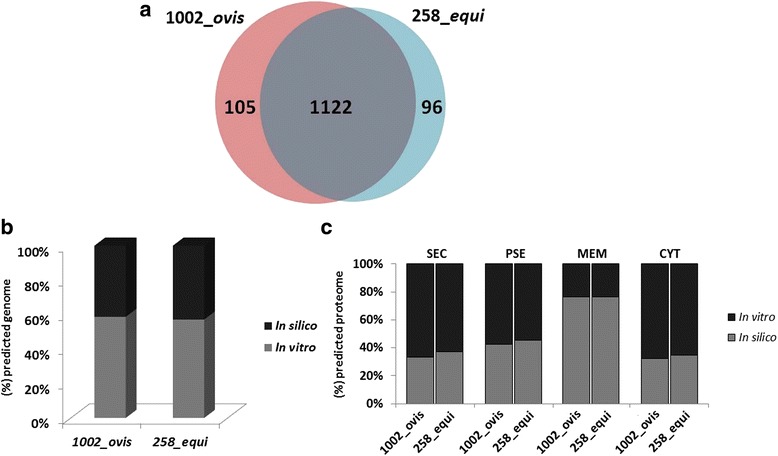

In this study, we applied the 2D nanoUPLC-HDMSE approach to characterize the proteome of the strains 1002_ovis and 258_equi. Both strains were grown in BHI media, subsequently proteins were extracted and digested in solution, and then the peptides were analyzed by LC/MSE. Our proteomic analysis identified a total of 1227 non-redundant proteins in 1002_ovis (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 3: Table S2) and 1218 in 258_equi (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 4: Table S3) (Fig. 1a). The information about sequence coverage and a number of identified peptides for each protein sequence identified, as well as the information about the native peptide are available at Additional file 5: Table S4 and Additional file 6: Table S5. Altogether from the proteome of these two biovars, we identified a total of 1323 different proteins of C. pseudotuberculosis with high confidence (Fig. 1a) and characterized approximately 58% of the predicted proteome of 1002_ovis [11] (Fig. 1b). In the case of 258_equi, we characterized approximately 57% of the predicted proteome [12] (Fig. 1b). The proteins identified in both proteomes were analyzed by SurfG+ tool [27] to predict the subcellular localization into four categories: cytoplasmic (CYT), membrane (MEM), potentially surface-exposed (PSE) and secreted (SEC) (Fig. 1c). Further, we identified 83% (43 proteins) of the lipoproteins predicted in 1002_ovis and 79% (41 proteins) in 258_equi. Considering proteins with LPxTG motif which are involved in covalent linkage with peptidoglycan, we identified 6 proteins in 1002_ovis and 4 proteins in 258_equi that correspond to approximately 38% and 34% of the LPxTG proteins predicted in each strain, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the proteome of C. pseudotuberculosis and correlation with in silico data. a Distribution of the proteins identified in the proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi, represented by Venn diagram. b Correlation of the proteomic results with in silico data of the genomes of 1002_ovis and 258_equi. c Subcellular localization of the identified proteins and correlation with the in silico predicted proteome. CYT, cytoplasmic; MEM, membrane; PSE, potentially surface-exposed and SEC, secreted

The biovar equi and biovar ovis core proteome

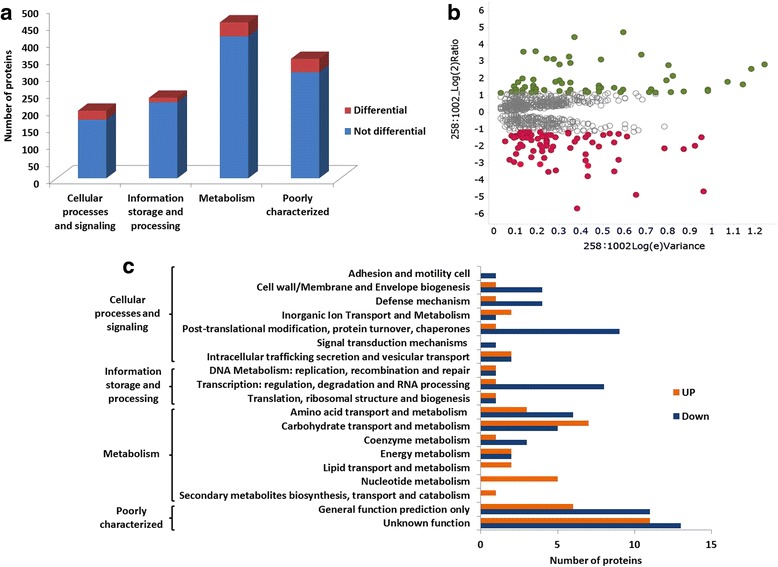

The core-proteome, between 258_equi and 1002_ovis is composed of 1122 proteins (Fig. 1) (Additional file 2: Table S1). Interestingly, when correlated these 1122 proteins with in silico data of the C. pseudotuberculosis core-genome [10], we observed that 86% (960 proteins) of the Open Reading Frame (ORF) that encodes these proteins are part of the core-genome (Additional file 2: Table S1), what represents approximately 64% of the predicted core-genome of this pathogen. In addition, these data show a set of proteins involved in different cellular processes which could be necessary for the free living of C. pseudotuberculosis. The other 14% (262 proteins) of the proteins that constitute the core-proteome are shared by at least one of the 15 strains used in the core-genome study. According to Gene Ontology analysis [31, 32], the 1122 proteins were classified into four important functional groups: (i) metabolism, (ii) information storage and processing, (iii) cellular processes and signaling, and (iv) poorly characterized (Fig. 2a). As observed in the study of C. pseudotuberculosis [10] core genome in the categories “metabolism” and “information storage and processing” were detected a large number of proteins.

Fig. 2.

Representative results of the core-proteome 1002_ovis and 258_equi. a Functional distribution of the proteins identified in the core-proteome. b Volcano plot generated by differentially expressed proteins, log2 ratio of 258_equi/1002_ovis. c Biological processes differential between 258_equi and 1002_ovis

The label-free quantification was applied to evaluate the relative abundance of the core-proteome of 258_equi and 1002_ovis. The ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS) v2.5.2 software with ExpressionE algorithm tool was used to identify proteins with p ≤ 0.05 (Additional file 2: Table S1). Among these proteins, 120 proteins between 258_equi and 1002_ovis showed difference in level of abundance (log2 ratios equal or greater than a factor of 1.2) [26] (Table 1). In this group of proteins that have presented different abundance level (258_equi:1002_ovis), 49 proteins were more abundant and 71 less abundant (Table 1). To visualize this differential distribution of the core-proteome a volcano plot of the log2 ratio of 258_equi/1002_ovis versus Log (e) Variance was generated (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, the Phospholipase D (Pld), the major virulence factor of C. pseudotuberculosis, was more abundant in 258_equi, than in 1002_ovis (Table 1). The Pld have an important play role in the pathogenic process of C. pseudotuberculosis, due to the sphingomyelinase activity of the Pld, this exotoxin increases vascular permeability through the exchange of polar groups attached to membrane-bound lipids and helps the bacteria in spread inside the host [34, 35]. In addition, this exotoxin is able to reduce the viability of both macrophages and neutrophils [34, 36]. In comparative proteomic studies between 1002_ovis and C231_ovis exoproteome, Pld was detected only in the C231_ovis supernatant [13, 15, 16]. A study performed with pld mutant strains presented decreased virulence [37]. Thus, in relation to 258_equi, 1002_ovis could present a low potential of virulence.

Table 1.

Differentially regulated proteins between 258_equi and 1002_ovis

| Accession | Description | 258:1002 Log(2)Ratio(a) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 258_equi | 1002_ovis | Score | p_value(a) | ||

| Cellular processes and signaling | |||||

| Adhesion and motility cell | |||||

| I3QUW8_CORPS | D9Q5S4_CORP1 | Periplasmic zinc binding protein troA | 4245,52 | -1,32 | 0 |

| Cell wall/Membrane and Envelope biogenesis | |||||

| I3QYI6_CORPS | D9Q3G9_CORP1 | Phospho N acetylmuramoyl pentapeptide | 166,05 | 1,22 | 1 |

| I3QZH4_CORPS | D9Q4F8_CORP1 | Corynomycolyl transferase | 3886,67 | -1,45 | 0 |

| I3R044_CORPS | D9Q526_CORP1 | Peptidoglycan recognition proteino | 5283,55 | −2,06 | 0 |

| D9Q4M0_CORP1 | Cell wall channel | 2220,85 | −2,14 | 0 | |

| I3QYK8_CORPS | D9Q3J1_CORP1 | Cell wall peptidase NlpC P60 protein | 1207,7 | −2,78 | 0 |

| Defense mechanism | |||||

| I3QW82_CORPS | D9Q743_CORP1 | Cold shock protein | 6171,9 | 1,37 | 1 |

| I3R0B7_CORPS | D9Q597_CORP1 | DNA protection during starvation protein | 70,504,73 | −1,48 | 0 |

| I3QV66_CORPS | D9Q632_CORP1 | Cold shock protein | 31,703,46 | −2458 | 0 |

| I3QZX1_CORPS | D9Q4V4_CORP1 | Protein GrpE | 57,665,59 | −2,64 | 0 |

| I3QZW9_CORPS | D9Q4V2_CORP1 | Heat shock protein HspR | 929,96 | −3,43 | 0 |

| Intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport | |||||

| I3QVC7_CORPS | D9Q697_CORP1 | ABC type transporter | 376,36 | 2,91 | 1 |

| I3QZ34_CORPS | D9Q431_CORP1 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein | 6339,11 | 1,54 | 1 |

| I3QZQ5_CORPS | D9Q4N9_CORP1 | ABC superfamily ATP binding cassette | 25,578,26 | −1,38 | 0 |

| I3R0D8_CORPS | D9Q5B9_CORP1 | Oligopeptide transport system permease | 705,01 | −1,45 | 0,01 |

| Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |||||

| I3QWY7_CORPS | D9Q7U6_CORP1 | Thioredoxin TrxA | 1832,12 | 3,15 | 1 |

| I3QVC2_CORPS | D9Q692_CORP1 | Thiol disulfide isomerase thioredoxin | 157,88 | 1,80 | 1 |

| I3QXH3_CORPS | D9Q8C5_CORP1 | Proteasome accessory factor PafA2 | 305,06 | −1,32 | 0 |

| I3QZA4_CORPS | D9Q493_CORP1 | Glutaredoxin like protein nrdH | 3140,61 | −1,34 | 0 |

| I3QUL7_CORPS | D9Q5I3_CORP1 | Peptidyl prolyl cis trans isomerase | 49,161,11 | −1,44 | 0 |

| I3QWQ3_CORPS | D9Q7L6_CORP1 | Ferredoxin | 54,332,67 | −1,48 | 0 |

| I3QW91_CORPS | D9Q753_CORP1 | Peptidyl prolyl cis trans isomerase | 19,736,36 | −1,63 | 0 |

| I3QV23_CORPS | D9Q5Y2_CORP1 | Catalase | 52,016,22 | −1,70 | 0 |

| I3QUX7_CORPS | D9Q5T5_CORP1 | Glyoxalase Bleomycin resistance protein | 18,489,51 | −1,99 | 0 |

| I3QVR1_CORPS | D9Q6M3_CORP1 | 10 kDa chaperonin | 90,387,73 | −2,78 | 0 |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | |||||

| I3QY22_CORPS | D9Q8W9_CORP1 | Phosphocarrier protein HPr | 38,569,08 | −2,92 | 0 |

| Information storage and processing | |||||

| DNA Metabolism: replication, recombination and repair | |||||

| I3QV41_CORPS | D9Q606_CORP1 | Metallophosphoesterase | 529,63 | 1,88 | 1 |

| I3QWM2_CORPS | Exodeoxyribonuclease 7 small subunit | 10,725,45 | −2,00 | 0 | |

| Transcription: regulation, degradation and RNA processing | |||||

| I3QX71_CORPS | D9Q817_CORP1 | SAM dependent methyltransferase y | 397,16 | 1,25 | 0,96 |

| I3QWD6_CORPS | D9Q7A0_CORP1 | TetR family regulatory protein | 5685,08 | −1,38 | 0 |

| I3QXS5_CORPS | D9Q8M5_CORP1 | N utilization substance protein B homol | 16,977,04 | −1,42 | 0 |

| I3QWH0_CORPS | D9Q7D4_CORP1 | Transcriptional regulatory protein PvdS | 7456,32 | −1,48 | 0 |

| I3QYU0_CORPS | D9Q3T4_CORP1 | Ferric uptake regulatory protein | 7805,46 | −1,76 | 0 |

| I3QWK3_CORPS | D9Q7G7_CORP1 | Transcription elongation factor GreA | 77,246,3 | −1,87 | 0 |

| I3QZJ2_CORPS | D9Q4H4_CORP1 | Transcriptional regulator | 10,476,01 | −1,93 | 0 |

| I3QUZ7_CORPS | D9Q5V6_CORP1 | Nucleoid associated protein ybaB | 81,447,09 | −3,04 | 0 |

| I3QUU4_CORPS | D9Q5Q1_CORP1 | YaaA protein | 25,362,05 | −3,14 | 0 |

| Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | |||||

| I3R0I2_CORPS | D9Q5F9_CORP1 | Ribosomal RNA small subunit methyltrans | 395,99 | 1,29 | 1 |

| I3QWD9_CORPS | D9Q7A3_CORP1 | 30S ribosomal protein S14 | 4756,75 | −1,47 | 0 |

| Metabolism | |||||

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | |||||

| D9Q3B4_CORP1 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | 1534,86 | 3,56 | 1 | |

| I3QXI1_CORPS | D9Q8D2_CORP1 | Aspartate ammonia lyase | 2326,21 | 1,60 | 1 |

| I3QWF9_CORPS | D9Q7C4_CORP1 | Glycine betaine transporter | 136,23 | 1,21 | 1 |

| I3QV21_CORPS | D9Q5Y0_CORP1 | Aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 8778,47 | −1,28 | 0 |

| I3QWZ5_CORPS | D9Q7V4_CORP1 | Cysteine desulfurase | 1813,31 | −1,31 | 0 |

| I3QXT1_CORPS | D9Q8N1_CORP1 | Chorismate synthase | 5341,49 | −1,41 | 0 |

| I3QXI5_CORPS | D9Q8D5_CORP1 | Phosphoribosyl ATP pyrophosphatase | 25,184,13 | −1,90 | 0 |

| I3QXL8_CORPS | D9Q8G8_CORP1 | UPF0237 protein Cp258 1096 | 16,011,21 | −1,96 | 0 |

| I3QZZ5_CORPS | D9Q4X5_CORP1 | Urease subunit beta | 4349,97 | −2,12 | 0 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | |||||

| I3R0E6_CORPS | D9Q5C6_CORP1 | Aldose 1 epimerase | 221,55 | 2,78 | 1 |

| I3QV93_CORPS | D9Q660_CORP1 | Formate acetyltransferase 1 | 9381,31 | 2,00 | 1 |

| I3QZB7_CORPS | D9Q4A5_CORP1 | Phosphoglucomutase | 359,43 | 1,77 | 1 |

| I3QWW1_CORPS | D9Q7S1_CORP1 | L lactate permease | 103,53 | 1,38 | 0,99 |

| D9Q8W7_CORP1 | PTS system fructose specific EIIABC | 191,71 | 1,35 | 1 | |

| I3QY20_CORPS | D9Q8W6_CORP1 | 1 phosphofructokinase | 2879,52 | 1,32 | 1 |

| I3R064_CORPS | D9Q545_CORP1 | L lactate dehydrogenase | 5695,04 | 1,32 | 1 |

| I3R051_CORPS | D9Q691_CORP1 | Probable phosphoglycerate mutase | 2014,4 | −1,24 | 0 |

| D9Q396_CORP1 | PTS system fructose specific IIABC | 507,53 | −1,25 | 0 | |

| I3QWR8_CORPS | D9Q7N1_CORP1 | Sucrose 6 phosphate hydrolase | 6075,08 | −1,34 | 0 |

| I3QYN0_CORPS | D9Q3L2_CORP1 | Glycine cleavage system H proteino | 91,529,52 | −1,38 | 0 |

| I3QWH7_CORPS | D9Q7D8_CORP1 | Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase | 9529,4 | −2,68 | 0 |

| Coenzyme metabolism | |||||

| D9Q862_CORP1 | ATP dependent dethiobiotin synthetase B | 104,92 | −1,24 | 1 | |

| I3QUY1_CORPS | D9Q5T9_CORP1 | Pyridoxal biosynthesis lyase PdxSo | 1029,15 | −1,42 | 0 |

| I3QXF8_CORPS | D9Q8B1_CORP1 | Precorrin 8X methyl mutase | 34,981,98 | −1,77 | 0 |

| I3QXE1_CORPS | D9Q893_CORP1 | Hemolysin related protein | 3609,76 | 1,35 | 0 |

| Energy metabolism | |||||

| I3QUS5_CORPS | D9Q5N2_CORP1 | NADH dehydrogenase | 3257,66 | 3,14 | 1 |

| I3QZ12_CORPS | D9Q411_CORP1 | Malate dehydrogenase | 11,220,59 | 1,22 | 1 |

| I3QXN4_CORPS | D9Q8I5_CORP1 | Cytochrome oxidase assembly protein | 297,19 | −1,86 | 0,09 |

| I3QYB6_CORPS | D9Q3A4_CORP1 | Nitrogen regulatory protein P II | 16,165,93 | −2,29 | 0 |

| Inorganic Ion Transport and Metabolism | |||||

| I3R097_CORPS | D9Q575_CORP1 | Cation transport protein | 882,31 | −4,64 | 1 |

| I3QZG5_CORPS | D9Q4F0_CORP1 | Trk system potassium uptake protein trk | 2973,22 | 1,25 | 1 |

| I3QVU4_CORPS | D9Q6Q3_CORP1 | Hemin binding periplasmic protein hmuT | 607,64 | 1,71 | 1 |

| I3QVT3_CORPS | D9Q6P2_CORP1 | Manganese ABC transporter substrate binding | 3917,5 | 1,51 | 0 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | |||||

| I3QUM7_CORPS | D9Q5J0_CORP1 | Phospholipase D | 25,847,67 | 3,27 | 1 |

| I3QZM9_CORPS | D9Q4L5_CORP1 | Secretory lipase | 1254 | 3,08 | 1 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | |||||

| I3QZR5_CORPS | D9Q4P8_CORP1 | Purine phosphoribosyltransferase | 227,51 | 4,45 | 1 |

| I3QZF7_CORPS | D9Q4E2_CORP1 | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synth | 978,57 | 1,45 | 1 |

| I3QXV6_CORPS | D9Q8Q6_CORP1 | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferaseo | 907,16 | 1,44 | 1 |

| I3QZ07_CORPS | D9Q406_CORP1 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 14,996,33 | 1,35 | 1 |

| I3QZG8_CORPS | D9Q4F3_CORP1 | HIT family protein | 4039,81 | 1,21 | 1 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | |||||

| I3QWA4_CORPS | D9Q766_CORP1 | Multidrug resistance protein norMo | 208,76 | 1,35 | 0,98 |

| Poorly characterized | |||||

| General function prediction only | |||||

| I3QXE6_CORPS | D9Q898_CORP1 | Methyltransferase type 11 | 102,29 | 2,84 | 0,99 |

| I3QWH3_CORPS | D9Q7D6_CORP1 | Enoyl CoA hydratase | 225,9 | 2,14 | 1 |

| D9Q5M7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 2201,88 | 1,93 | 1 | |

| I3QZJ7_CORPS | D9Q4I2_CORP1 | Carbonic anhydrase | 550,46 | 1,81 | 1 |

| I3QWR6_CORPS | D9Q7M9_CORP1 | Unknown function | 246,05 | 1,24 | 0,98 |

| I3QX38_CORPS | Cutinase | 11,245,11 | −1,48 | 0 | |

| I3QXY3_CORPS | D9Q8T2_CORP1 | Chlorite dismutase | 32,986,51 | −1,51 | 0 |

| I3QW56_CORPS | D9Q720_CORP1 | Methylmalonyl CoA carboxyltransferase 1 | 4283,03 | −1,52 | 0 |

| I3QWE6_CORPS | D9Q7B0_CORP1 | Serine protease | 5615,41 | −1,54 | 0 |

| I3QX14_CORPS | D9Q7X2_CORP1 | Aldo keto reductase | 6121,73 | −1,63 | 0 |

| I3QWR9_CORPS | D9Q7N2_CORP1 | Alpha acetolactate decarboxylase | 1839,59 | −1,73 | 0 |

| I3QUU3_CORPS | D9Q5Q0_CORP1 | UPF0145 protein Cp258 0101 | 3922,57 | −1,77 | 0 |

| I3QV73_CORPS | D9Q639_CORP1 | Hydrolase domain containing protein | 5759,37 | −2,23 | 0 |

| I3QZM7_CORPS | D9Q4L2_CORP1 | Rhodanese related sulfurtransferase | 7428,74 | −2,46 | 0 |

| I3QYY9_CORPS | D9Q3Y7_CORP1 | Ankyrin domain containing proteino | 11,948,84 | −2,84 | 0 |

| I3QW24_CORPS | D9Q6Y4_CORP1 | Hydrolase domain containing protein | 15,589,93 | −3,04 | 0 |

| Unknown function | |||||

| I3R0H3_CORPS | D9Q5F1_CORP1 | Unknown function | 7862,73 | 3,59 | 1 |

| I3QX01_CORPS | D9Q7W0_CORP1 | Unknown function | 276,68 | 3,43 | 1 |

| I3QYP3_CORPS | D9Q3P0_CORP1 | Unknown function | 1609,29 | 2,84 | 1 |

| I3QWZ8_CORPS | D9Q7V7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 1476,56 | 2,58 | 1 |

| I3R0H2_CORPS | D9Q5F0_CORP1 | Unknown function | 572,19 | 1,90 | 1 |

| I3QY71_CORPS | D9Q919_CORP1 | Unknown function | 1466,6 | 1,78 | 1 |

| I3QWL3_CORPS | D9Q7H7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 304,96 | 1,65 | 0,98 |

| I3QUW1_CORPS | D9Q5R7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 504,13 | 1,60 | 1 |

| I3QYF2_CORPS | D9Q3D7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 985,97 | 1,47 | 1 |

| I3QWR5_CORPS | D9Q7M8_CORP1 | Unknown function | 103,03 | 1,45 | 1 |

| I3QVG0_CORPS | D9Q6C8_CORP1 | Unknown function | 4085,83 | 1,39 | 1 |

| I3QXI8_CORPS | D9Q8D8_CORP1 | Unknown function | 87,929,25 | −1,35 | 0 |

| I3QVZ1_CORPS | D9Q6U7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 64,404,7 | −1,38 | 0 |

| I3R094_CORPS | D9Q572_CORP1 | Unknown function | 4367,05 | −1,68 | 0 |

| I3QYW4_CORPS | D9Q3V8_CORP1 | Unknown function | 15,928,9 | −1,96 | 0 |

| I3QUX9_CORPS | D9Q5T7_CORP1 | Unknown function | 8100,51 | −2,00 | 0 |

| I3QYG8_CORPS | D9Q3F3_CORP1 | Unknown function | 78,035,52 | −2,09 | 0 |

| I3QUZ5_CORPS | D9Q5V4_CORP1 | Unknown function | 77,763,68 | −2,09 | 0 |

| I3QUR3_CORPS | D9Q5M1_CORP1 | Unknown function | 12,731,48 | −2,27 | 0 |

| I3QVV7_CORPS | D9Q6R6_CORP1 | Unknown function | 8564,11 | −3,47 | 0 |

| I3QXX0_CORPS | D9Q8S0_CORP1 | Unknown function | 19,485,3 | −3,50 | 0 |

| I3QW02_CORPS | D9Q6W1_CORP1 | Unknown function | 49,581,23 | −3,76 | 0 |

| I3QVS0_CORPS | D9Q6N1_CORP1 | Unknown function | 66,162,63 | −4,87 | 0 |

| I3R0G5_CORPS | D9Q5E4_CORP1 | Unknown function | 39,265,48 | −5,65 | 0 |

The 120 differential proteins were organized by cluster of orthologous groups, and when evaluated the different biological processes that comprise each category listed above, we observed that 19 process were differentials between 258_equi and 1002_ovis (Fig. 2c, Additional file 7: Figure S2 and Additional file 8: Figure S3). The majority of the more abundant proteins (258_equi:1002_ovis) are related to cellular metabolism. On other hand, the majority of the less abundant proteins (258_equi:1002_ovis) are classified as poorly characterized or of unknown function. However, when proteins of known or predicted function are evaluated the majority of the less abundant proteins are related to cellular processes and signaling.

Difference among the major functional classes identified from the core-proteome analysis of 1002_ovis and 258_equi

Metabolism

During the infection process, pathogens need to adjust their metabolism in response to nutrient availability inside and outside the host. In our proteomic study, we identified several proteins related to different metabolic pathways. To determine the metabolic network of each strain, the proteins identified in this study were analyzed using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes pathways and Genomes (KEGG) [38]. A total of 321 and 320 proteins, corresponding to 1002_ovis and 258_equi respectively, were mapped onto different metabolic pathways (Additional file 9: Figure S4 and Additional file 10: Figure S5). We observed differences in the metabolism of the biovars, related to Amino acid transport and metabolism, Carbohydrate transport and metabolism, Coenzyme metabolism, Energy metabolism, Lipid transport and metabolism, Nucleotide metabolism and Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism. Difference in the metabolism cellular, also already were observed in others comparative proteomic study of C. pseudotuberculosis [13, 16, 17, 19], as well as in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogen [39].

Interestingly, the PTS system fructose-specific EIIABC component (PstF) related to carbohydrate metabolism was more abundant in 258_equi, than in 1002_ovis (Table 1). This protein showed increased abundance in field isolates of C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis grown in BHI when compared to C231_ovis, a reference strain [19]. This increased abundance of PstF in 258_equi, suggests that this protein could be important to the transport of carbon source both biovar ovis and biovar equi strains. On the other hand, the Precorrin 8X methyl mutase involved in cobalamin and vitamin B12 synthesis can be required only in biovar ovis strains, this protein beside being more abundant in 1002_ovis (Table 1), was also detected with greater abundance in the field isolates of C. pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis after having been grown in BHI [19]. Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) was detected more abundant in 258_equi (Table 1). A study performed with the M. bovis pathogen showed that GDH contributes to the survival of this pathogen during macrophage infection [40].

In C. pseudotuberculosis, it was demonstrated that genes related the iron-acquisition are involved in the virulence of this pathogen [41]. In the core-proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi, we detected proteins involved in this process, like CiuA, FagC and FagD; however, all these proteins were not differentially regulated between the two strains (Additional file 2: Table S1). On the other hand, HmuT protein, related to hemin uptake, was more abundant in 258_equi (Table 1). Additionally, we have also detected a cell surface hemin receptor in the exclusive proteome of this strain. Heme represents the major reservoir of iron source for many bacterial pathogens that rely on surface-associated heme-uptake receptors [42]. The HmuT is a lipoprotein that acts as a hemin receptor. The hmuT gene is part of the operon hmuTUV, an ABC transport system (haemin transport system), which is normally present in pathogenic Corynebacterium [43, 44]. In addition, in the pathogen C. ulcerans, HmuT is required for normal hemin utilization [44].

Information storage and processing

Of the total protein of proteins identify in the category “information storage and processing” the majority of the differential proteins were less abundant in 258_equi (Table 1). Only, Metallophosphoesterase involved in DNA repair, SAM dependent methyltransferase related to transcriptional process and Ribosomal RNA small subunit methyltransferase I involved in translation process were more induced in 258_equi. In 1002_ovis the Exodeoxyribonuclease 7 important protein related to the DNA-damage pathway was more induced in this strain. In addition, we identified the TetR family regulatory protein as more abundant in 1002_ovis, this result was also observed in field isolates of C. pseudotuberculosis from sheep infected naturally [19]. TerR proteins are related to regulation of multidrug efflux pumps, antibiotic biosynthesis, catabolic process and cellular differentiation process [45]. Others important transcriptional regulators also were induced in 1002_ovis such as PvdS and GreA regulators.

Cellular processes and signaling

Our proteomic analyses detected differentially regulated proteins belonging to different antioxidant systems. These could contribute to the survival of C. pseudotuberculosis in various stress conditions, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which are generally found in macrophage. The three major thiol-dependent antioxidant systems in prokaryotic pathogens are the thioredoxin system (Trx), the glutathione system (GSH-system) and the catalase system [46]. Thioredoxin TrxA and Thiol-disulfide isomerase thioredoxin were more abundant in 258_equi (Table 1). These proteins are involved in the Trx-system, which has a major role against oxidative stress [46]. However, proteins like catalase and glutaredoxin (nrdH) were less abundant in 258_equi (Table 1), being more active in 1002_ovis. Catalase plays an important role in resistance to ROS and RNS, as well as in the virulence of M. tuberculosis [47]. The protein NrdH has a glutaredoxin amino acid sequence and thioredoxin activity. It is present in Escherichia coli [48] and C. ammoniagenes [49], as well as in bacteria where the GSH system is absent, such as M. tuberculosis [50]. Thus, the presence of NrdH may represent one more factor that contributes to the resistance of C. pseudotuberculosis against ROS and RNS during the infection process, as well as to the maintenance of the balance of intracellular redox potential. Proteins like NorB and Glyoxalase/Bleomycin, which play roles in the nitrosative stress response of 1002_ovis, were identified in the exclusive proteome of this strain (Additional file 3: Table S2) [14, 18]. These results shown that beside of present proteins with difference in abundance both strains present a set of proteins that could contribute to adaptive process under stress conditions.

Difference proteomic observed in the exclusive proteome of 258_equi and 1002_ovis

We found respectively 105 and 96 proteins in the exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi (Fig. 1) (Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3), related to different biological process (Additional file 7: Figure S2 and Additional file 8: Figure S3). Interestingly, in this exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi, we detected specific proteins in each strain (Table 2, Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3). In the exclusive proteome of 258_equi, the ORFs that codify twenty proteins are annotated as pseudogene in 1002_ovis (Table 2, Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3). On the other hand, the ORFs that encode six proteins were not detected in the genome of 1002_ovis. These proteins are two CRISPR, MoeB, and three unknown function proteins. CRISPR is an important bacterial defense system against infections by viruses or plasmids, this immunity is obtained from the integration of short sequences of invasive DNA ‘spacers’ into the CRISPR loci [51].

Table 2.

Exclusive proteins identified in 258_equi and 1002_ovis

| Locus | Locus | Description | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1002_ovis | |||

| Cp1002_1457 | − | DNA methylaseb | DNA Metabolism: replication, recombination and repair |

| Cp1002_1872 | Cp258_1887 | Collagen binding surface protein Cnad | Adhesion and motility cell |

| Cp1002_1859 | Cp258_1875 | Sdr family related adhesind | Adhesion and motility cell |

| Cp1002_2025 | Cp258_2050 | Glycoside hydrolase 15 related proteind | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| Cp1002_0387 | Cp258_0396 | Neuraminidase Sialidased | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| Cp1002_0262 | Cp258_0266 | Ppx/GppA phosphatase familyd | General function prediction only |

| Cp1002_1151 | Cp258_1168 | Zinc metallopeptidased | General function prediction only |

| Cp1002_0077 | Cp258_0091 | Unknown functiond | Unknown function |

| 258_equi | |||

| Cp258_0374 | − | MoeB proteina | Coenzyme metabolism |

| Cp258_1675 | − | CRISPR associated proteina | DNA Metabolism: replication, recombination and repair |

| Cp258_0028 | − | CRISPR-associated proteina | DNA Metabolism: replication, recombination and repair |

| Cp258_0076 | − | Unknown functiona | Unknown function |

| Cp258_0585 | − | Unknown functiona | Unknown function |

| Cp258_0586 | − | Unknown functiona | Unknown function |

| Cp258_0896 | Cp1002_0888 | Acetolactate synthasec | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| Cp258_0465 | Cp1002_0455 | Cystathionine gamma synthasec | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| Cp258_0313 | Cp1002_0310 | Aminopeptidase Gc | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| Cp258_0893 | Cp1002_0884 | Dihydroxy acid dehydratasec | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| Cp258_1223 | Cp1002_1203 | Inositol 1 monophosphatasec | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| Cp258_1360 | Cp1002_1337 | Unknown functionc | Coenzyme metabolism |

| Cp258_1909 | Cp1002_1892 | Aldehyde dehydrogenasec | Energy metabolism |

| Cp258_0123 | Cp1002_0109 | ABC type metal ion transport systemc | Inorganic Ion Transport and Metabolism |

| Cp258_1854 | Cp1002_1838 | Disulfide bond formation protein DsbBc | Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| Cp258_0395 | Cp1002_0386 | Methionine aminopeptidasec | Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| Cp258_1923 | Cp1002_1906 | Oligopeptide binding protein oppAc | Intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport |

| Cp258_1549 | Cp1002_1541 | ABC transporter ATP binding proteinc | Intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport |

| Cp258_1566 | Cp1002_1561 | ABC transporterc | Intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport |

| Cp258_0693 | Cp1002_0689 | Phosphatase YbjIc | General function prediction only |

| Cp258_1503 | Cp1002_1497 | Alpha beta hydrolasec | General function prediction only |

| Cp258_1265 | Cp1002_1243 | Unknown functionc | General function prediction only |

| Cp258_0169 | Cp1002_0157 | NADPH dependent nitro flavin reductasec | General function prediction only |

| Cp258_1351 | Cp1002_1329 | Unknown functionc | Unknown function |

| Cp258_1916 | Cp1002_1899 | Unknown functionc | Unknown function |

| Cp258_2099 | Cp1002_2077 | Unknown functionc | Unknown function |

(a) Strain-specific protein, ORF detected only in the genome of 258_equi

(b)Strain-specific protein, ORF detected only in the genome of 1002_ovis

(c) ORF predicted like pseudogene in 1002_ovis

(d) ORF predicted like pseudogene in 258_equi

The distinction between the biovar ovis and biovar biovar equi strains is based on a biochemical assay, where biovar ovis strains are negative for nitrate reduction, whereas biovar equi strains are positive [52]. However, to date, there is no available information regarding the molecular basis underlying nitrate reduction in C. pseudotuberculosis biovar equi. MoeB is involved in the molybdenum cofactor (Moco) biosynthesis, which plays an important role in anaerobic respiration in bacteria and also are required to activation of nitrate reductase (NAR) [53]. In the closely related pathogen M. tuberculosis several studies have showed the great importance of molybdenum cofactor in its virulence and pathogenic process, mainly macrophage intracellular environmental [54]. Therefore, more studies are necessary to explore the true role of Moco both physiology and virulence of biovar equi strains. Other protein that also could contribute to resistance of 258_equi macrophage is NADPH dependent nitro/flavin reductase (NfrA), a pseudogene in 1002_ovis. In addition, studies performed in Bacillus subtilis showed that NfrA is involved in both oxidative stress [55] and heat shock resistance [56].

In 1002_ovis, only the ORF that encodes a DNA methylase was not found in the 258_equi genome (Table 2, Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3). In addition, the ORFs that codifies seven proteins identified in the exclusive proteome of the strain 1002_ovis are annotated like pseudogene in 258_equi (Table 2, Additional file 3: Table S2 and Additional file 4: Table S3). Inside this group, we have identified important proteins involved in the process of adhesion and invasion cellular, which might contribute in the pathogenesis of 1002_ovis. Adhesion to host cells is a crucial step that favors the bacterial colonization; this process is mediated by different adhesins [57]. We identified proteins such as: collagen binding surface protein Cna-like and Sdr family related adhesin, which are members of the collagen-binding microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) (Table 2). This class of proteins is present in several Gram positive pathogens and plays an important role in bacterial virulence by acting mainly in the cellular adhesion process [58–61].

Another detected protein that might contribute to the virulence of 1002_ovis is Neuraminidase (NanH) (Table 2). This protein belongs to a class of glycosyl hydrolases that contributes to the recognition of sialic acids exposed on host cell surfaces [62]. In C. diphtheriae, it was demonstrated that a protein with trans-sialidase activity promotes cellular invasion [63, 64]. In addition, NanH was reported to be immunoreactive in the immunoproteome of 1002_ovis, showing the antigenicity of this protein [65]. Interestingly, genomic difference in relation to gene involved in the adhesion and invasion process, also already were observed between biovar ovis strain and biovar equi strains, mainly in genes related to pilus [10, 12]. According to pathogenic process of each biovar, unlike biovar equi strains, which rarely causes visceral lesions [4], biovar ovis strains, are responsible mainly by visceral lesions [2, 35], what requires a high ability to adhere and invade the host cell, thus these protein could be responsible by this ability of biovar ovis strain in attacks visceral organs.

Proteogenomic analysis

In our proteomic analysis, the measured MS/MS spectra from the proteomic datasets of 1002_ovis and 258_equi were searched against a concatenated database composed by genome annotation of 1002_ovis CP001809.2 version and 258_equi CP003540.2 version for identify possible errors or unannotated genes. Thus, by adopting more stringent criteria of considering only proteins with a minimum representative of two peptides and a FDR < 1%, we identified five proteins in 1002_ovis and seven proteins in 258_equi, which were not previously annotated. All parameters, as well as, the peptides sequence which were used for identification of these proteins are shown in Additional file 11: Table S6 and Additional file 12: Table S7. The proteins identified in this proteogenomic analysis are associated to different biological processes. For instance, the Aminopeptidase N involved in the amino acid metabolism was detected in 1002_ovis, whereas the Cobaltochelatase (cobN), associated to cobalt metabolism, glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) involved in the L-glutamate metabolism, the PTS system fructose specific EIIABC related to fructose metabolism and the Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase involved in the purine biosynthesis were all detected in 258_equi. Proteins involved in DNA processes, such as Uracil DNA glycosylase in 258_equi; and Exodeoxyribonuclease 7 small subunit in 1002_ovis were also detected in both strains. Proteins with general function prediction only and unknown function were also identified in both strains.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we used a label-free quantitative approach to compare, for the first time, the proteome of C. pseudotuberculosis strains belonging to both ovis and equi biovars. Taken together, the findings reported here show a set of shared and exclusive factors of 1002_ovis and 258_equi at the protein level, which can contribute to understanding both the physiology and the virulence of these strains. In addition, the functional analysis of the genome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi allows the in silico validation of data of the genome of these strains. Thus, the proteins identified here may be used as potential new targets for the development of vaccines against ovis and equi C. pseudotuberculosis in future investigations.

Availability of supporting data

The datasets supporting the results of this article were then concatenated into a *xlsx file at peptide and protein level to fulfill the requirements and is available at supplemental material including sequence coverage and a number of identified peptides for each protein sequence identified. It also includes the native peptide information.

Additional files

Growth rates in BHI media of 1002_ovis (blue circles) and 258_equi (red triangles). (JPEG 278 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the core-proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi. (XLSX 215 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis. (XLSX 20 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the exclusive proteome of 258_equi. (XLSX 21 kb)

Total list of peptide and proteins identified 1002_ovis. (XLSB 31769 kb)

Total list of peptide and proteins identified 258_equi. (XLSB 33204 kb)

The protein-protein interaction network of 1002_ovis. (A) General interactome of differentially regulated proteins, identified in the exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis. The proteins are marked with different shapes: exclusive proteome, circle; more abundant, square; less abundant, rhombus. The biological processes were marked with different colors: amino acid transport and metabolism, yellow; secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, aquamarine; inorganic ion transport and metabolism, orange; coenzyme metabolism, brown; carbohydrate transport and metabolism, chartreuse green; nucleotide metabolism, cerulean; energy metabolism, olive; lipid transport and metabolism, viridian; adhesion and motility cell, crimson; iuntracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport, persian blue; signal transduction mechanisms, maroon; cell wall/membrane and envelope, gray; defense mechanism, red; post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, electric blue; DNA metabolism, replication, recombination and repair, violet; translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, amber; transcription, regulation, degradation and RNA processing, salmon; poorly characterized, white. (JPEG 3310 kb)

The protein-protein interaction network of 258_equi. (A) General interactome of the differentially regulated proteins, identified in the exclusive proteome of 258_equi. The proteins are marked with different shapes: exclusive proteome, circle; more abundant, square; less abundant, rhombus. The biological processes are marked with different colors: amino acid transport and metabolism, yellow; secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, aquamarine; inorganic ion transport and metabolism, orange; coenzyme metabolism, brown; carbohydrate transport and metabolism, chartreuse green; nucleotide metabolism, cerulean; energy metabolism, olive; lipid transport and metabolism, viridian; adhesion and motility cell, crimson; intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport, persian blue; signal transduction mechanisms, maroon; cell wall/membrane and envelope, gray; defense mechanism, red; post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, electric blue; DNA metabolism, replication, recombination and repair, violet; translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, amber; transcription, regulation, degradation and RNA processing, salmon; poorly characterized, white. (JPEG 4178 kb)

Metabolic network of 1002_ovis. Red line, proteins identified in the proteomic analysis, other colors represent proteins not identified in this study. (JPEG 8633 kb)

Metabolic network of 258_equi. Red line, proteins identified in the proteomic analysis, other colors represent proteins not identified in this study. (JPEG 1267 kb)

Proteins identified in 1002_ovis by Proteogenomics. (XLSX 216 kb)

Proteins identified in 258_equi by Proteogenomics. (XLSX 266 kb)

Acknowledgment

This work involved the collaboration of various institutions, including the Genomics and Proteomics Network of the State of Pará of the Federal University of Pará, the Amazon Research Foundation (FAPESPA), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), the Minas Gerais Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) and the Waters Corporation, Brazil.

Authors’ contributions

WMS performed microbiological analyses and sample preparation for proteomic analysis. GHMFS and WMS conducted the proteomic analysis. SCS and ELF performed bioinformatics analysis of the data. CSS, AVS, AM and HF contributed substantially to data interpretation and revisions. VA, AS and YLL participated in all steps of the project as coordinators, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics approval was required for any aspect of this study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- 2D-RP

Two-dimensional reversed phase

- C

Citosine

- FDR

False discovery rate

- G

Guanine

- HSS

High strength silica

- LC/MS

Liquid chromatograph mass spectrometry

- nanoESI-HDMS

Nano Electrospray High Definition Mass Spectrometry

- nanoUPLC

Nano Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography

- nanoUPLC-MS

Nano Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PLGS

Protein Lynx Global Server

- RNS

Reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3835-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Wanderson M. Silva, Email: silvamarques@yahoo.com.br

Edson L. Folador, Email: edson.folador@gmail.com

Siomar C. Soares, Email: siomars@gmail.com

Gustavo H. M. F. Souza, Email: Gustavosouza@waters.com

Agenor V. Santos, Email: valadaresantos@gmail.com

Cassiana S. Sousa, Email: cassissousa@gmail.com

Henrique Figueiredo, Email: figueiredoh@yahoo.com.

Anderson Miyoshi, Email: miyoshi@icb.ufmg.br.

Yves Le Loir, Email: yves.leloir@rennes.inra.fr.

Artur Silva, Email: asilva@ufpa.br.

Vasco Azevedo, Phone: +55 31 3409 2610, Email: vasco@icb.ufmg.br.

Reference

- 1.Dorella FA, Pacheco LG, Oliveira SC, Miyoshi A, Azevedo V. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: microbiology, biochemical properties, pathogenesis and molecular studies of virulence. Vet Res. 2006;37:201–218. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird GJ, Fontaine MC. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and its role in ovine caseous lymphadenitis. J Comp Pathol. 2007;137:179–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shpigel NY, Elad D, Yeruham I, Winkler M, Saran A. An outbreak of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in an Israeli dairy herd. Vet Rec. 1993;133:89–94. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.4.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britz E, Spier SJ, Kass PH, Edman JM, Foley JE. The relationship between Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biovar equi phenotype with location and extent of lesions in horses. Vet J. 2014;200:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selim SA. Oedematous skin disease of buffalo in Egypt. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2001;48:241–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paton MW, Walker SB, Rose IR, Watt GF. Prevalence of caseous lymphadenitis and usage of caseous lymphadenitis vaccines in sheep flocks. Aust Vet J. 2002;81:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb11443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley JE, Spier SJ, Mihalyi J, Drazenovich N, Leutenegger CM. Molecular epidemiologic features of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis isolated from horses. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:1734–1737. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seyffert N, Guimarães AS, Pacheco LG, Portela RW, Bastos BL, Dorella FA, et al. High seroprevalence of caseous lymphadenitis in Brazilian goat herds revealed by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis secreted proteins-based ELISA. Res Vet Sci. 2010;88:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar J, Singh F, Tripathi BN. Kumar 454 R, Dixit SK, Sonawane GG. Epidemiological, bacteriological and molecular studies on caseous lymphadenitis in Sirohi goats of Rajasthan, India. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:1319–1322. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soares SC, Silva A, Trost E, Blom J, Ramos R, Carneiro A, et al. The pan-genome of the animal pathogen Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis reveals differences in genome plasticity between the biovar ovis and biovar equi strains. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz JC, D’Afonseca V, Silva A, Ali A, Pinto AC, Santos AR, et al. Evidence for reductive genome evolution and lateral acquisition of virulence functions in two Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis strains. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soares SC, Trost E, Ramos RTJ, Carneiro AR, Santos AR, Pinto AC, et al. Genome sequence of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biovar equi strain 258 and prediction of antigenic targets to improve biotechnological vaccine production. J Biotechnol. 2012;20:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pacheco LG, Slade SE, Seyffert N, Santos AR, Castro TL, Silva WM, et al. A combined approach for comparative exoproteome analysis of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 2011;17:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pacheco LG, Castro TL, Carvalho RD, Moraes PM, Dorella FA, Carvalho NB, et al. A Role for Sigma Factor σ(E) in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis Resistance to Nitric Oxide/Peroxide Stress. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:126. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva WM, Seyffert N, Santos AV, Castro TL, Pacheco LG, Santos AR, et al. Identification of 11 new exoproteins in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis by comparative analysis of the exoproteome. Microb Pathog. 2013;16:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva WM, Seyffert N, Ciprandi A, Santos AV, Castro TL, Pacheco LG, et al. Differential Exoproteome analysis of two Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis strains isolated from goat (1002) and sheep (C231) Curr Microbiol. 2013;67:460–465. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rees MA, Kleifeld O, Crellin PK, Ho B, Stinear TP, Smith AI, et al. Proteomic characterization of a natural host-pathogen interaction: repertoire of in vivo expressed bacterial and host surface-associated proteins. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:120–132. doi: 10.1021/pr5010086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva WM, Carvalho RD, Soares SC, Bastos IF, Folador EL, Souza GH, et al. Label free proteomic analysis to confirm the predicted proteome of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis under nitrosative stress mediated by nitric oxide. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1065. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees MA, Stinear TP, Goode RJA, Coppel RL, Smith AI, Kleifeld O. Changes in protein abundance are observed in bacterial isolates from a natural host. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:71. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP, Geromanos SJ. Absolute quantification of proteins by LC-MSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:144–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Two-dimensional separation of peptide using RP-RP-HPLC system with different pH in first and second separation dimensions. J Sep Sci. 2005;28:1694–1703. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva JC, Denny R, Dorschel CA, Gorenstein M, Kass IJ, Li GZ, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal Chem. 2005;1:2187–2200. doi: 10.1021/ac048455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geromanos SJ, Vissers JP, Silva JC, Dorschel CA, Li GZ, Gorenstein MV, et al. The detection, correlation, and comparison of peptide precursor and product ions from data independent LC-MS with data dependant LC-MS/MS. Proteomics. 2009;9:1683–1695. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li GZ, Vissers JP, Silva JC, Golick D, Gorenstein MV, Geromanos SJ. Database searching and accounting of multiplexed precursor and product ion spectra from the data independent analysis of simple and complex peptide mixtures. Proteomics. 2009;9:1696–1719. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin Y, Hradetzky E, Bahn S. Quantification of proteins using data-independent analysis (MSE) in simple andcomplex samples: a systematic evaluation. Proteomics. 2011;11:3273–3287. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barinov A, Loux V, Hammani A, Nicolas P, Langella P, Ehrlich D, et al. Prediction of surface exposed proteins in Streptococcus pyogenes, with a potential application to other Gram-positive bacteria. Proteomics. 2009;9:61–73. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendtsen JD, Kiemer L, Fausboll A, Brunak S. Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juncker AS, Willenbrock H, Von Heijne G, Brunak S, Nielsen H, Krogh A. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1652–1662. doi: 10.1110/ps.0303703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conesa A, Gotz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;15:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, et al. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKean SC, Davies JK, Moore RJ. Expression of phospholipase D, the major virulence factor of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, is regulated by multiple environmental factors and plays a role in macrophage death. Microbiology. 2007;7:2203–2211. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/005926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batey RG. Pathogenesis of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep and goats. Aust Vet J. 1986;63:269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1986.tb08064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yozwiak ML, Songer JG. Effect of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis phospholipase D on viability and chemotactic responses of ovine neutrophils. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:392–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamara PJ, Bradley GA, Songer JG. Targeted mutagenesis of the phospholipase D gene results in decreased virulence of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:921–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunawardena HP, Feltcher ME, Wrobel JA, Gu S, Braunstein M, Chen X. Comparison of the membrane proteome of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the attenuated Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine strain by label-free quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2013;6:5463–5474. doi: 10.1021/pr400334k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallant JL, Viljoen AJ, van Helden PD, Wiid IJ. Glutamate Dehydrogenase Is Required by Mycobacterium bovis BCG for Resistance to Cellular Stress. PLoS One. 2016;29:e0147706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billington SJ, Esmay PA, Songer JG, Jost BH. Identification and role in virulence of putative iron acquisition genes from Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;19:41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Contreras H, Chim N, Credali A, Goulding CW. Heme uptake in bacterial pathogens. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;19:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drazek ES, Hammack AC, Schmitt PM. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from hemin and hemoglobin are homologous to ABC hemin transporters. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:68–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitt MP, Drazek SE. Construction and consequences of directed mutations affecting the hemin receptor in pathogenic Corynebacterium species. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1476–1481. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1476-1481.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramos JL, Martínez-Bueno M, Molina-Henares AJ, Terán W, Watanabe K, Zhang X, et al. The TetR family of transcriptional repressors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:326–356. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.326-356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;8:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng VH, Cox JS, Sousa AO, MacMicking JD, McKinney JD. Role of KatG catalase peroxidase in mycobacterial pathogenesis: countering the phagocyte oxidative burst. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1291–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jordan A, Aslund F, Pontis E, Reichard P, Holmgren A. Characterization of Escherichia coli NrdH. A glutaredoxin-like protein with a thioredoxin-like activity profile. J Biol Chem. 1997;18:18044–18050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stehr M, Lindqvist Y. NrdH-redoxin of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes forms a domain-swapped dimer. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinform. 2004;55:613–619. doi: 10.1002/prot.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leiting WU, Jianping XI. Comparative genomics analysis of Mycobacterium NrdH redoxins. Microb Pathog. 2010;48:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang W, Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas: New Tools for Genetic Manipulations from Bacterial Immunity Systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;15:209–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biberstein EL, Knight HD, Jang S. Two biotypes of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Vet Rec. 1971;25:691–692. doi: 10.1136/vr.89.26.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leimkühler S, Iobbi-Nivol C. Bacterial molybdoenzymes: old enzymes for new purposes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015;13:1–18. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams M, Mizrahi V, Kana BD. Molybdenum cofactor: a key component of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis? Crit Rev Microbiol. 2014;40:18–29. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.749211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mostertz J, Scharf C, Hecker M, Homuth G. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis gene expression in response to superoxide and peroxide stress. Microbiology. 2004;150:497–512. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moch C, Schrögel O, Allmansberger R. Transcription of the nfrA-ywcH operon from Bacillus subtilis is specifically induced in response to heat. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4384–4393. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.16.4384-4393.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers EA, Das A, Ton-That H. Adhesion by pathogenic corynebacteria. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;715:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0940-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patti JM, Allen BL, McGavin MJ, Hook M. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:585–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lannergard J, Frykberg L, Guss B. CNE, a collagen-binding protein of Streptococcus equi. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;222:69–74. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nallapareddy SR, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium exhibit strain-specific collagen binding mediated by Acm, a new member of the MSCRAMM family. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1733–1747. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang M, Ko YP, Liang X, Ross CL, Liu Q, Murray BE, et al. Collagen-binding Microbial Surface Components Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecule (MSCRAMM) of Gram-positive Bacteria Inhibit Complement Activation via the Classical Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013;12:20520–20531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vimr ER, Kalivoda KA, Deszo EL, Steenbergen SM. Diversity of microbial sialic acid metabolism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:132–153. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.132-153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mattos-Guaraldi AL, Duarte Formiga LC, Pereira GA. Cell surface components and adhesion in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1507–1512. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim S, Oh DB, Kwon O, Kang HA. Identification and functional characterization of the NanH extracellular sialidase from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Biochem. 2010;147:523–533. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seyffert N, Silva RF, Jardin J, Silva WM, Castro TL, Tartaglia NR, et al. Serological proteome analysis of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis isolated from different hosts reveals novel candidates for prophylactics to control caseous lymphadenitis. Vet Microbiol. 2014;7:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth rates in BHI media of 1002_ovis (blue circles) and 258_equi (red triangles). (JPEG 278 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the core-proteome of 1002_ovis and 258_equi. (XLSX 215 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis. (XLSX 20 kb)

Total list of proteins identified in the exclusive proteome of 258_equi. (XLSX 21 kb)

Total list of peptide and proteins identified 1002_ovis. (XLSB 31769 kb)

Total list of peptide and proteins identified 258_equi. (XLSB 33204 kb)

The protein-protein interaction network of 1002_ovis. (A) General interactome of differentially regulated proteins, identified in the exclusive proteome of 1002_ovis. The proteins are marked with different shapes: exclusive proteome, circle; more abundant, square; less abundant, rhombus. The biological processes were marked with different colors: amino acid transport and metabolism, yellow; secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, aquamarine; inorganic ion transport and metabolism, orange; coenzyme metabolism, brown; carbohydrate transport and metabolism, chartreuse green; nucleotide metabolism, cerulean; energy metabolism, olive; lipid transport and metabolism, viridian; adhesion and motility cell, crimson; iuntracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport, persian blue; signal transduction mechanisms, maroon; cell wall/membrane and envelope, gray; defense mechanism, red; post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, electric blue; DNA metabolism, replication, recombination and repair, violet; translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, amber; transcription, regulation, degradation and RNA processing, salmon; poorly characterized, white. (JPEG 3310 kb)

The protein-protein interaction network of 258_equi. (A) General interactome of the differentially regulated proteins, identified in the exclusive proteome of 258_equi. The proteins are marked with different shapes: exclusive proteome, circle; more abundant, square; less abundant, rhombus. The biological processes are marked with different colors: amino acid transport and metabolism, yellow; secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, aquamarine; inorganic ion transport and metabolism, orange; coenzyme metabolism, brown; carbohydrate transport and metabolism, chartreuse green; nucleotide metabolism, cerulean; energy metabolism, olive; lipid transport and metabolism, viridian; adhesion and motility cell, crimson; intracellular trafficking secretion and vesicular transport, persian blue; signal transduction mechanisms, maroon; cell wall/membrane and envelope, gray; defense mechanism, red; post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, electric blue; DNA metabolism, replication, recombination and repair, violet; translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, amber; transcription, regulation, degradation and RNA processing, salmon; poorly characterized, white. (JPEG 4178 kb)

Metabolic network of 1002_ovis. Red line, proteins identified in the proteomic analysis, other colors represent proteins not identified in this study. (JPEG 8633 kb)

Metabolic network of 258_equi. Red line, proteins identified in the proteomic analysis, other colors represent proteins not identified in this study. (JPEG 1267 kb)

Proteins identified in 1002_ovis by Proteogenomics. (XLSX 216 kb)

Proteins identified in 258_equi by Proteogenomics. (XLSX 266 kb)