Abstract

A detailed clinical and cytogenetic survey for the fragile-X syndrome was undertaken on 201 institutionalized mentally retarded males with no previously recognized cause of retardation, and the causes of mental retardation were summarized from a total of 595 institutionalized male and female patients after the review of their medical records including clinical and cytogenetic data. Among the 201 males clinically and cytogenetically examined, five (2·5%) had abnormal chromosome findings with four (2%) having the fragile-X syndrome. Twelve of the males (6·0%) were diagnosed with a single gene disorder. In the present study, mental retardation was classified as possibly due to multifactorial causes when a genetic syndrome, chromosome abnormality or environmental insult was not identified, but mental retardation was present in one or more first and/or second degree relatives, but did not follow a recognizable inheritance pattern. Hence, mental retardation was recorded in other family members and may indicate possible multifactorial causes in 45 males (22·4%). An environmental insult was noted in 25 males (12·4%); unexplained birth defects in three males (1·5%); a specific condition or diagnosis identified, but cause unknown (e.g. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome) in 10 males (5%); and no diagnosis made in the remaining 101 males (50·2%). Of all 595 patients (334 males and 261 females), including the 201 males who had undergone a detailed clinical and cytogenetic evaluation, 39 (6·6%) had abnormal chromosome findings, with Down’s syndrome noted in 31 of the patients. Twenty-five patients (4·2%) were diagnosed with a single gene disorder while mental retardation was noted in other family members and may indicate possible multifactorial causes in 64 patients (10·8%). An environmental insult was noted in 170 patients (28·6%); unexplained birth defects in 17 patients (2·9%); a specific condition or diagnosis but cause unknown in 27 patients (4·5%); and no diagnosis made in 253 patients (42·5%). Clinical and cytogenetic screening of mentally retarded patients for the fragile-X syndrome and other causes of mental retardation is helpful in identifying individuals and their families who may benefit from genetic services such as counseling and treatment. This study was performed over an approximate 2 year period from 1987 to 1989.

INTRODUCTION

Severe mental retardation is found in about 0·3–0·4% of the general population, and in approximately 10% of the mentally retarded (Emery & Rimoin 1990). There are 20% more males than females in institutions for the mentally retarded and approximately 100 X-linked mental retardation syndromes described (Opitz 1986). It has been estimated that X-linked genes account for about 25% of mental retardation in males and 10% of learning problems in females (Turner et al. 1980). Although several conditions contribute to X-linked mental retardation, the fragile-X syndrome accounts for 30–50% of families with mentally retarded males. The fragile-X syndrome is characterized by mental retardation, an elongated face, large and prominent ears, macroorchidism, mild connective tissue dysplasia, and fragile-X chromosome (Xq27.3) expression in 4% of cells from males and 2% from females when the cells are grown in folate-deficient culture conditions (Chudley & Hagerman 1987; Hagerman 1987; Butler 1988). Therefore, the fragile-X syndrome is a significant cause of mental deficiency in our society and is the second most common chromosome abnormality, after trisomy 21 or Down’s syndrome, among the mentally retarded.

The prevalence of chromosome anomalies in mentally retarded males in earlier studies before the fragile-X syndrome was recognized ranged from 11·9% (Speed et al. 1976) to 17·6% (Sutherland et al. 1976). Institutional screening of mentally retarded males for the fragile-X syndrome produced a range of 1·6% (Sutherland 1982) to 6·2% (Froster-Iskenius et al. 1983).

Recently, Hagerman et al. (1988) reported that large ears, macroorchidism and hand callouses in mentally retarded males would yield positive fragile-X chromosome results in 50% of these patients. Butler et al. (1991a, b) reported that certain physical characteristics (e.g. ear width, testicular volume, bizygomatic diameter, head breadth, plantar crease and hyperflexibility) could be used to correctly classify fragile-X syndrome in 97% of mentally retarded males with no previously identified cause of their mental retardation. Butler et al. (1992) also reported standards for selected anthropometric measurements in males with the fragile-X syndrome.

Herein, the present authors summarize their experience in determining the clinical and cytogenetic causes of mental retardation in 595 institutionalized male and female residents with emphasis on the prevalence of the fragile-X syndrome in the males.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

At the time of the present study, there were 595 mentally retarded residents (334 males and 261 females) between the ages of 4 and 88 years, with an average age of 39·4 years, and with an approximate average IQ of 20 institutionalized at Clover Bottom Developmental Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. Approximately 80% of the patients were Caucasian. Two hundred and one of the 334 males were examined by a clinical geneticist (M.G.B.) for a recognizable genetic syndrome, and medical records reviewed by both authors. Blood was obtained for chromosome analysis including for the fragile-X syndrome. Clinical examination included taking 31 anthropometric measurements (weight, height, eight linear, four breadth, 14 craniofacial, two skinfolds and testicular volume), recording of behavioural characteristics (e.g. tactile defensiveness, hand flapping and poor eye contact) and reviewing of medical records. Of the remaining 133 males, 112 were not evaluated because a medically documented cause of their mental retardation (e.g. chromosome abnormalities, specific syndromes, birth trauma and environmental insults) was previously identified, but several patients with specific diagnoses (e.g. Down’s syndrome and de Lange syndrome) were examined for confirmation. Twenty-one males were not examined due to lack of cooperation.

Because the cause of mental retardation including the fragile-X syndrome in males was emphasized in the present study, female patients were not physically examined although medical records were reviewed. The medical records were analysed including chromosome findings from the patients without a recognizable cause of their retardation in order to identify causes of mental retardation.

Cytogenetics

Peripheral blood was cultured for 96 h in both Medium 199 (a folate-deficient culture medium) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum. Each medium was adjusted to a pH of 7·6. After 72 h, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUdR) was added to the RPMI 1640 medium cultures to a final concentration of 10−7 mol 1−1 to enhance fragile site expression. Cells from both cultures were routinely harvested, stained with Giemsa and analysed for fragile sites. If fragile sites were observed, the chromosomes were destained then G-banded after trypsinization and the location of the fragile sites noted. Seventy-five cells were studied from each patient (e.g. 50 cells from Medium 199 and 25 cells from RPMI 1640 medium) and three karyotypes from each patient were analysed for structural abnormalities. The diagnosis of the fragile-X syndrome was made if 4% of the patient’s cells were positive for the Xq27.3 fragile site. Approximately 80% of the 595 patients had chromosome studies performed previously or at the time of this study, particularly in those individuals with no known cause of their retardation.

RESULTS

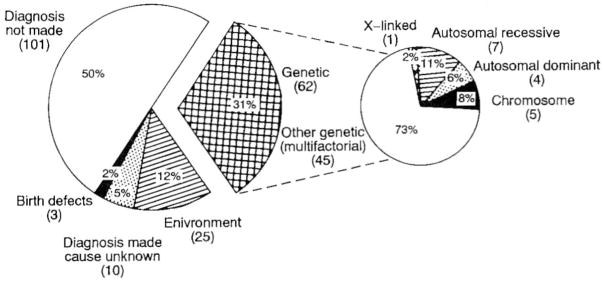

One hundred of the 201 male patients without a previously recognized cause of their mental retardation demonstrated a presumed cause of their retardation after a detailed clinical and cytogenetic evaluation. Five males (2·5%) had an abnormal chromosome study with four (2·0%) having the fragile-X syndrome and one male (0·5%) with a ring chromosome 22 karyotype. Twelve males (6·0%) were diagnosed with a single gene condition (e.g. autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked) after physical examination and review of available medical and family histories. Forty-five mentally retarded males (22·4%) were identified with no physical findings consistent with a genetic syndrome, but interestingly, mental retardation was noted in one or more first-degree (e.g. sibling) or second-degree (e.g. aunt) relatives, but did not follow a specific inhertance pattern and implied other unrecognized genetic factors or possibly multifactorial causes. After review of the patient’s medical and family histories, some of their mentally retarded relatives were as severely affected, but most were mildly affected. An environmental insult (e.g. birth anoxia, infection) was noted in 25 males (12·4%) and unexplained developmental or birth defects were seen in three males (1·5%). Additionally, a specific condition or diagnosis was identified, but the cause unknown (e.g. Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome) in 10 males (5%). Table 1 shows the apparent cause of mental retardation identified while screening the 201 previously undiagnosed males. Table 2 shows the diagnostic summary data from these individuals. Figure 1 graphically displays the causes of mental retardation in the 201 males.

Table 1.

Causes of mental retardation identified while screening previously undiagnosed males for the fragile-X syndrome

| Diagnosis | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis not made | 101 | 50·2 |

| Genetic disorders: | ||

| autosomal dominant: | ||

| tuberous sclerosis | 4 | 2·0 |

| autosomal recessive: | ||

| primary microcephaly | 2 | 1·0 |

| consanguinity (e.g. first cousins) | 2 | 1·0 |

| familial mental retardation★ | 3 | 1·5 |

| x-linked recessive: | ||

| familial mental retardation† | 1 | 0·5 |

| chromosome: | ||

| ring chromosome 22 syndrome | 1 | 0·5 |

| fragile-x syndrome | 4 | 2·0 |

| other genetic/multifactorial: | ||

| mental retardation‡ | 45 | 22·4 |

| Environment: | ||

| trauma: | ||

| birth trauma/anoxia | 7 | 3·5 |

| postnatal injury: | ||

| febrile reaction | 2 | 1·0 |

| post polio immunization reaction | 1 | 0·5 |

| head trauma | 1 | 0·5 |

| drugs: | ||

| foetal alcohol syndrome | 2 | 1·0 |

| foetal dilantin syndrome | 1 | 0·5 |

| prematurity (<7 months’ gestation) infection | 8 | 4·0 |

| viral: | ||

| TORCHS—unspecified | 3 | 1·5 |

| Birth defects: | ||

| malformation: | ||

| congenital hydrocephaly | 1 | 0·5 |

| hydranencephaly | 1 | 0·5 |

| MR/MCA | 1 | 0·5 |

| Diagnosis made but cause unknown: | ||

| communicating hydrocephaly | 1 | 0·5 |

| infantile autism | 3 | 1·5 |

| Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome | 1 | 0·5 |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome | 1 | 0·5 |

| microcephaly | 1 | 0·5 |

| Diagnosis made but causes unknown (continued): | ||

| neuromuscular disorder (unspecified type) | 1 | 0·5 |

| Proteus syndrome | 1 | 0·5 |

| cutis verticis gyrata | 1 | 0·5 |

| Total | 201 | 100 |

Mental retardation in siblings with similar clinical findings and degree of retardation.

Mental retardation in first or second degree relatives exhibiting an X-linked pattern of inheritance, but were negative for the fragile-X chromosome.

Mental retardation found in first- or second-degree relatives, but with no recognizable pattern of inheritance.

Table 2.

Summary of conditions found while screening 201 previously undiagnosed mentally retarded males

| Diagnosis | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis not made | 101 | 50·2 |

| Genetic disorders: | ||

| autosomal dominant | 4 | 2·0 |

| autosomal recessive | 7 | 3·5 |

| chromosome | 5 | 2·5 |

| X-linked | 1 | 0·5 |

| other genetic/multifactorial | 45 | 22·4 |

| Environmental insult | 25 | 12·4 |

| Birth defects | 3 | 1·5 |

| Diagnosis made but cause unknown | 10 | 5·0 |

Figure 1.

Pie chart showing summarized data of the causes of mental retardation found while screening 201 previously undiagnosed males.

The present authors’ complete analysis of the 595 patients from the institution included the 201 males with detailed clinical and cytogenetic evaluation (see Table 1), and 394 individuals whose medical records including chromosome findings were reviewed in order to identify potential cause of their mental retardation. These individuals included: 242 patients (112 males and 130 females) with a documented medical cause of their retardation and the remaining 152 patients (131 females with no documented condition or cause of their mental retardation after reviewing the medical records including chromosome findings, and 21 males with no medically documented cause of mental retardation but who were not examined due to lack of cooperation). No identifiable cause of mental retardation was found in 253 patients (42·5%). A single gene disorder was identified in 25 patients (4·2%) and a positive family history for mental retardation but without a recognized inheritance pattern was seen in 64 patients (10·8%). Thirty-nine patients (6·6%) had chromosomal abnormalities. An environmental insult was recorded in 170 patients (28·6%), and unexplained developmental or birth defects identified in 17 patients (2·9%). A specific condition or diagnosis was identified, but the cause unknown (e.g. de Lange syndrome) in 27 patients (4·5%). Table 3 shows the frequency of causes of mental retardation identified in the 595 patients. Table 4 shows the diagnostic summary data from these individuals. Figure 2 graphically displays the causes of mental retardation in the 595 patients.

Table 3.

Causes of mental retardation identified in 595 institutionalized patients

| Diagnosis | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis not made | 253 | 42·5 |

| Genetic disorders: | ||

| Autosomal dominant: | ||

| tuberous sclerosis | 7 | 1·2 |

| Autosomal recessive: | ||

| primary microcephaly | 3 | 0·5 |

| consanguinity (e.g. first cousins) | 2 | 0·3 |

| phenylketonuria | 7 | 1·2 |

| sudanophilic leukodystrophy of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher type | 2 | 0·3 |

| familial mental retardation★ | 1 | 0·2 |

| X-linked recessive: | ||

| familial mental retardation† | 3 | 0·5 |

| Chromosome: | ||

| Down syndrome | 31 | 5·2 |

| ring chromosome 22 syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| fragile-X syndrome‡ | 4 | 0·7 |

| 46,XX,12p- | 1 | 0·2 |

| cri-du-chat syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| unspecified chromosome abnormality | 1 | 0·2 |

| Other genetic/multifactorial: | ||

| mental retardation§ | 64 | 10·8 |

| Environment: | ||

| Trauma: | ||

| birth trauma/anoxia | 52 | 8·7 |

| Postnatal injury: | ||

| hyperthermia | 2 | 0·3 |

| post polio immunization reaction | 1 | 0·2 |

| post immunization reaction | 1 | 0·2 |

| head trauma | 1 | 0·2 |

| hypoxia | 4 | 0·7 |

| injury (unspecified) | 11 | 1·8 |

| Drugs: | ||

| fetal alcohol syndrome | 2 | 0·3 |

| fetal dilantin syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| intoxication, toxaemia of pregnancy | 3 | 0·5 |

| Prematurity: | ||

| <28 weeks gestation | 15 | 2·5 |

| 29–37 weeks gestation | 27 | 4·5 |

| Infection: | ||

| Viral: | ||

| postnatal cerebral — unspecified | 4 | 0·6 |

| TORCHS — unspecified | 2 | 0·3 |

| congenital rubella | 7 | 1·2 |

| congenital syphilis | 2 | 0·3 |

| cytomegalic inclusion disease | 4 | 0·7 |

| Bacterial: | ||

| postnatal cerebral — unspecified | 18 | 3·0 |

| Unspecified type: | ||

| postnatal cerebral — unspecified | 13 | 2·2 |

| Birth defects: | ||

| malformation: | ||

| congenital hydrocephaly | 1 | 0·2 |

| hydranencephaly | 1 | 0·2 |

| MR/MCA — unspecified | 6 | 1·0 |

| craniostenosis | 2 | 0·3 |

| meningomyelocele | 4 | 0·7 |

| other cerebral malformations | 2 | 0·3 |

| other craniofacial anomalies | 1 | 0·2 |

| Diagnosis made but cause unknown: | ||

| communicating hydrocephaly | 1 | 0·2 |

| infantile autism | 3 | 0·5 |

| Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| microcephaly | 3 | 0·5 |

| neuromuscular disorder (unspecified type) | 1 | 0·2 |

| Proteus syndrome | 1 | 0·2 |

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome | 5 | 0·8 |

| cutis verticis gyrata | 1 | 0·2 |

| hyperbilirubinemia intoxication | 4 | 0·7 |

| macrocephalus | 1 | 0·2 |

| congenital thyroid dysfunction | 2 | 0·3 |

| other endocrine disorder (not thyroid) | 1 | 0·2 |

| other fibre tracts or neural groups, degenerative | 1 | 0·2 |

| tumors — unspecified type or location | 1 | 0·2 |

| Total | 595 | 100 |

Mental retardation in siblings with similar clinical findings and degree of retardation.

Mental retardation in first- or second-degree relatives exhibiting an X-linked pattern of inheritance.

Only males without a cause of their mental retardation (n=201) were screened for the fragile-X syndrome.

Mental retardation found in first or second degree relatives but with no recognizable pattern of inheritance.

Table 4.

Summary of diagnoses made in 595 mentally retarded institutionalized patients

| Diagnosis | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis not made | 253 | 42·5 |

| Genetic disorders: | ||

| autosomal dominant | 7 | 1·2 |

| autosomal recessive | 15 | 2·5 |

| chromosome | 39 | 6·6 |

| X-linked | 3 | 0·5 |

| other genetic/multifactorial | 64 | 10·8 |

| Environmental insult | 170 | 28·6 |

| Birth defects | 17 | 2·9 |

| Diagnosis made but cause unknown | 27 | 4·5 |

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing summarized data of the causes of mental retardation in 595 institutionalized mentally retarded patients.

Several clinical findings recorded in the 201 males physically examined were: macro-orchidism [testicular volume ≥ 25 ml (≥ ninety-seven centile) for adults] in 47% of the male patients with an average testicular size of 26·8 ml; hypogonadism [testicular volume ≤9 ml (≤third centile) for adults] in 2% of patients, macrocephaly [head circumference ≥59 cm (≥ninety-eighth centile) for adults] in 5% of patients with an average head circumference of 55·1 cm ±2·6; microcephaly [head circumference ≤53 cm (≤second centile) for adults] in 20% of patients; obesity [weights≥81·65 kg (≥ninety-seventh centile) for adults] in 7% of patients with an average weight of 63·9± 12·07 kg; underweight [weight ≤49·90 kg (≤third centile) for adults] in 9% of patients; tall stature [height ≥187·96 cm (2≥ninety-seventh centile) for adults] was not seen in any of the present authors’ patients, with an average height of 166·88±10·41 cm; and short stature [height ≤161·93 cm ≤third centile) for adults] in 23% of patients. Additional clinical findings included history of seizures in 43% of the males, female history of mental retardation/autism (e.g. affected first- or second-degree relatives) but not psychiatric illnesses in 36%, keratoconus in 3%, and cryptorchidism in 3% of the patients.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to identify the frequency of the fragile-X syndrome among mentally retarded males without a previously documented cause of their retardation, and to summarize the documented medical and genetic causes of retardation in institutionalized patients of both sexes in view of current understanding of cytogenetic and clinical genetic syndromes as causes of mental retardation. The patients were screened with cytogenetic studies including for the fragile-X syndrome in the males without a previous cause of their mental retardation, but physical examination of the males performed by a clinical geneticist and by reviewing the medical and family histories of all patients. No cause of mental retardation was found in 50% (101 out of 201) of the male patients examined clinically and cytogenetically, but an apparent genetic disorder (e.g. tuberous sclerosis) was identified in 31% (62 out of 201) of these males if one considers the males with a positive family history of mental retardation as representing possible multifactorial causes of retardation. (Table 1). For all 595 male and female patients analysed including the 201 males clinically and cytogenetically studied, 42% (253 out of 595) had no recognizable cause of their retardation and 22% (128 of 595) had a genetic disorder including possible multifactorial causes of mental retardation (Table 3).

Of the 201 males who had undergone a genetic evaluation, five (2·5%) had an abnormal chromosome study with the fragile-X syndrome accounting for four (2%) of those males. There is a wide range [1·1% (Brøndum-Nielsen et al. 1982) to 52% (Trusler & Beatty-De Sana 1985)] of fragile-X syndrome patients reported in the literature in previous selective institutional screening of males, and the present study is in agreement with other investigations of comparable size and patient selection (Hagerman et al. 1988).

The frequency of chromosome abnormalities in surveys of mentally retarded patients, excluding the fragile-X syndrome, has ranged from 3·9 to 17·6% (Kahkonen et al. 1983; Arinami et al. 1986; Hagerman et al. 1988; Pulliam et al. 1988; English et al. 1989). The present results are comparable to those reported in the literature in that 6% of the patients in this study, excluding the fragile-X syndrome, had a chromosome abnormality with Down’s syndrome accounting for 89% of those patients.

Previous studies on categorization of mentally retarded patients have shown that 44% of mental retardation is due to a prenatal problem in brain morphogenesis with about one-third of those patients having a single primary defect in brain morphogenesis such as primary microcephaly or hydrocephalus with the remaining two-thirds having multiple congenital anomalies including the brain (Kaveggia et al. 1973; Smith & Simons 1975; Jones 1988; Emery & Rimoin 1990). Of those patients with mental retardation and multiple congenital anomalies, 41 % have a chromosome disorder, mostly Down’s syndrome, 18% with a non-chromosomal syndrome and 41% with patterns of malformation of unknown aetiology. Approximately 3% of all mentally retarded patients have a documented perinatal insult of the brain (e.g. trauma, hemorrhage and anoxia), approximately 12% of patients have a documented postnatal onset of retardation such as environmental insults, metabolic disorders or infections, and an undiagnosed or undecided age of onset of retardation is seen in 41% of patients (Kaveggia et al. 1973; Jones 1988).

In this study of 201 males with no previously documented cause of mental retardation but with fragile-X chromosome studies, the present authors found that about one-fifth had a prenatal onset of brain morphogenesis (e.g. fragile-X syndrome, foetal alcohol syndrome). A perinatal insult [birth trauma and prematurity complications (e.g. intracerebral hemorrhage)] was identified in 7·5% of the 201 males with postnatal insults (e.g. head trauma and febrile reaction) were recorded in 2% of the males. No explanation for the mental retardation was found in 50% of the 201 males in this group.

In the 595 institutionalized patients, 32% were found to have a prenatal onset of their mental retardation. These percentages are similar to those reported in previous studies (Kaveggia et al. 1973; Jones 1988). Of the present 595 patients, 16% had a documented perinatal insult which was higher than the reported 3% in the literature (Kaveggia et al. 1973; Jones 1988); this may be due to a higher incidence of prematurity (and its complications) and birth trauma in the present study; 11 % were found to have had postnatal insults, which was similar to the reported 12% in the literature (Jones 1988); and 43% had no recognizable cause of their mental retardation, which was similar to the 41% reported in the literature (Kaveggia et al. 1973; Jones 1988).

In summary, the present authors’ clinical and cytogenetic data of institutionalized patients with mental retardation and emphasis on the fragile-X syndrome in males were similar to previously reported causes of mental retardation in other studies of comparable size. These data are useful in determining the cause and frequency of genetic and other conditions in mentally retarded individuals, and for planning and implementation of services for both institutionalized and non-institutionalized patients.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation for financial support. We thank G. Andy Allen, Karen King and Judy Haynes for technical assistance, and June Burns, Roberta Thomas and other health care providers at Clover Bottom Developmental Center. We also thank Pamela Grimm for preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Arinami T, Kondo I, Nakajima S. Frequency of the fragile-X syndrome in Japanese mentally retarded males. Human Genetics. 1986;73:309–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00279092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brøndum-Nielsen K, Tommerup N, Dyggve HV7, Schou C. Macroorchidism and fragile-X in mentally retarded males: clinical, cytogenetic and some hormonal investigations in mentally retarded males, including two with the fragile site at Xq28, Fra(X) (q28) Human Genetics. 1982;61:113–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00274199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG. Fragile-X syndrome: a major cause of X-linked mental retardation. Comprehensive Therapy. 1988;14:3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Allen GA, Haynes JL, Singh DN, Watson MS, Breg WR. Anthropometric comparison of mentally retarded males with and without the fragile-X syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1991a;38:260–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320380220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Mangrum T, Gupta R, Singh DN. A 15-item checklist for screening mentally retarded males for the fragile-X syndrome. Clinical Genetics. 1991b;39:347–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1991.tb03041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Brunschwig A, Miller LK, Hagerman RJ. Standards for selected anthropometric measurements in the fragile-X syndrome. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1059–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudley AE, Hagerman RJ. Fragile X syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics. 1987;110:821–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AEH, Rimoin DL. Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- English CJ, Davison EV, Bhate MS, Barrett L. Chromosome studies of males in an institution for the mentally handicapped. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1989;26:379–81. doi: 10.1136/jmg.26.6.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froster-Iskenius U, Felsch G, Schirren C, Schwinger E. Screening for fra(X) (q) in a population of mentally retarded males. Human Genetics. 1983;63:153–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00291535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ. Fragile-X syndrome. Current Problems in Pediatrics. 1987;17:621–74. doi: 10.1016/0045-9380(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman R, Berry R, Jackson AW, Campbell J, Smigh ACM, McGavran L. Institutional screening for the fragile-X syndrome. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1988;142:1216–21. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150110094028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL. Smith’s Recignizable Patterns of Human Malformation. W.B. Saunders & Co; Philadelphia, PA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kaveggia EG, Durkin MV, Pendleton E, Opitz JM. Diagnostic/genetic studies on 1224 patients with severe mental retardation. Proceedings of the 3rd Congress of the International Association for the Scientific Study of Mental Deficiency; Warsaw: Polish Medical Publishers; 1973. pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kahkonen M, Leisti J, Wilska M, Varonen S. Marker X-associated mental retardation: a study of 150 retarded males. Clinical Genetics. 1983;23:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1983.tb01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz JM. On the gates of hell and a most unusual gene. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1986;23:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320230102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam L, Wilkes G, Vanner L, Albiez K, Potts W, Rogers R, Schroer R, Saul R, Stevenson R, Phelan M. Fragile X syndrome. III. Frequency in facilities for the mentally retarded in South Carolina. In: Saul R, editor. Proceedings of the Greenwood Genetics Center. Jacob Press Inc; Clinton, SC: 1988. pp. 109–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Simons FER. Rational diagnostic evaluation of the child with mental deficiency. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1975;129:1285–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120480015006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed RM, Johnston AW, Evans HJ. Chromosome survey of total population of mentally subnormal in northeast of Scotland. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1976;13:295–306. doi: 10.1136/jmg.13.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland GR. Heritable fragile sites on human chromosomes VIII: preliminary population cytogenetic data on the folic-acid-sensitive fragile sites. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1982;34:452–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland GR, Murch AR, Gardiner AJ, Carter RF, Wiseman C. Cytogenetic survey of a hospital for the mentally retarded. Human Genetics. 1976;34:231–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00295286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusler S, Beatty-De Sana J. Fragile-X syndrome: a public health concern. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75:771–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.7.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G, Brookwell R, Daviel A, Selikotz M, Zilibowitz M. Heterozygous expression of X-linked mental retardation and the X chromosome marker (fraX) (q27) New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:662–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198009183031202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]