Abstract

Gliomas represent a broad spectrum of disease with life-expectancy outcomes ranging from months to decades. As our understanding of the molecular profiles of gliomas expands rapidly, practitioners are now better able to identify patients with favorable versus nonfavorable prognoses. Radiation therapy plays a key role in glioma treatment, improving disease control and oftentimes survival. However, for survivors, either long-term or short-term, radiation-induced cognitive impairments may negatively impact their quality of life. For patients with both favorable and unfavorable prognoses, intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) may offer significant, yet unproven benefits. IMPT is the newest and most advanced proton delivery technique, one with substantial benefits compared with historical proton techniques. IMPT allows practitioners to maximize the physical benefits of protons, increasing normal tissue sparing and reducing the potential for adverse effects. For more aggressive tumors, the dose conformality and normal tissue sparing afforded by IMPT may also allow for dose escalation to target volumes. However, in order to truly maximize the clinical potential of IMPT, the field of radiation oncology must not only implement the most advanced technologies, but also understand and capitalize on the unique biologic aspects of proton therapy.

Keywords: glioma, intensity modulated proton therapy, proton therapy

The Technological Development of IMPT

For clinical radiotherapy, the majority of current practice utilizes photon (also known as X-ray) beams. However, in addition to photon therapy, clinical radiation may also be delivered with particle therapy, the most common being proton therapy. Fewer than 1% of radiotherapy patients worldwide are treated with protons, though the number is increasing as new facilities are established. The rationale for the rapid establishment of proton centers can be explained through an understanding of the physical benefits of particle therapy compared with photons.

Photon radiation dose, as a function of depth in the patient, initially rises then declines exponentially as photons are absorbed. In other words, a photon beam deposits dose along the entire path between the entry and exit sites of the body. In contrast to photons, when protons penetrate matter, they slow down continuously as a function of depth. The rate of their energy loss (called linear energy transfer [LET]) increases with decreasing velocity. This dose deposition continues until the entire energy is depleted and then they come to an abrupt stop. This process of dose deposition produces a characteristic depth-dose curve termed the Bragg curve. The point of highest dose is called the Bragg peak. The depth of the peak (ie, the range of protons) is a function of initial energy. Dose deposited beyond the range is negligible. The practical benefits of protons can be seen in Fig. 1.

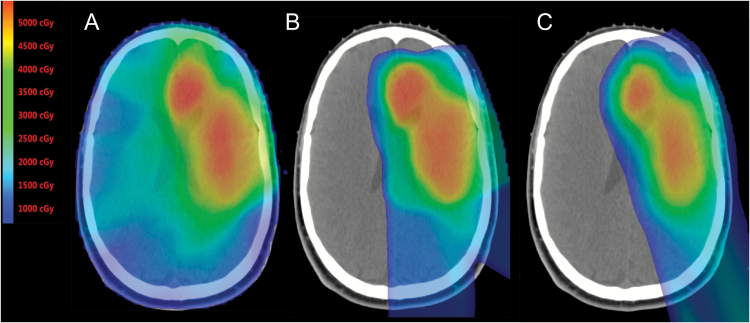

Fig. 1.

Color wash dose distributions for (A) IMRT (B) passively scattered and (C) intensity modulated proton therapy for a patient with a low-grade glioma. In comparing either proton plan to the IMRT plan, the low-dose sparing afforded by proton therapy is obvious. In comparison to photon plans, in patients with lateralized tumors such as this case, the dose to the contralateral brain, including areas important for learning and memory such as the hippocampus, is reduced to zero. Comparing proton plans, on close inspection there is improved conformality of high (orange and red) radiation doses as well as moderate doses (green) to the target volume. Skin dose with IMPT is also appreciably lower than either the passive scatter proton plan or IMRT plans.

For both photons and protons, the treatment technologies continue to evolve. In the early-1990s, radiotherapy with photons took a giant leap forward when intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) was introduced. With IMRT, each of a group of broad beams of photons is subdivided into narrow beamlets and delivered using dynamic multileaf collimators, which shape the beam. Following its introduction over 20 years ago, IMRT has continued to steadily evolve and is now considered both state of the art and standard of care for most malignancies. In IMRT, intensities of the beamlets are adjusted using optimization techniques to appropriately balance target and normal tissue dose distributions. IMRT allows considerable control to tailor dose distributions to achieve desired clinical objectives. However, given the inherent physical properties of photons, normal tissues surrounding the target volume still receive a substantial amount of unwanted dose, which often limits our ability to deliver curative dose to the tumor without unacceptable normal tissue toxicities.

In contrast to photon-based therapies such as IMRT, the expansion and development of proton therapy delivery techniques have been much slower. Passively scattered proton therapy (PSPT) has been used to treat the vast majority of cancer patients who have received proton therapy to date. In PSPT, physical devices such as beam scatterers and range modulating wheels are used to produce large cuboidal dose distributions of required dimensions and range, called the spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP). The SOBP is then shaped to each individual tumor volume by inserting customized hardware to create a dose distribution conforming to the target. Brass apertures are used to shape the lateral edges of the beam, whereas range compensators are used to shape the distal edge. Such compensators are typically made of a material such as Lucite and custom fabricated. Material is removed in areas where protons must travel farther in tissue to cover the target volume. PSPT may best be compared to pre-IMRT 3D conformal photon therapy, in an era in which techniques such as 3D conformal radiation and multiple broad photon beams were used to cover targets.

In contrast to PSPT, intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) uses spot scanning or “pencil” beam delivery. With spot-scanning proton therapy, a narrow pristine proton beam, a “beamlet,” is magnetically scanned to cover the lateral aspects of the target. Depth is controlled through a change of the proton beam energy. In contrast to PSPT, scanning-beam delivery offers greater control over the proximal aspects of the beam and improved conformality of high dose regions. This is especially true for newer facilities where improved technology has allowed for a reduction in the size of the beamlets (ie, smaller spot sizes). With small spot sizes on the order of 3 to 5 mm, practitioners essentially have a finer brush with which to paint radiation dose. In comparison to PSPT, IMPT when delivered with small pencil beams allows not only low-dose sparing but greatly improved conformality of the high dose regions.1

IMPT is a newly developing technology and there is perhaps much confusion in the field as to what constitutes IMPT. For many, simply using scanning beams in any manner constitutes IMPT. However, for treatment planning purposes, IMPT can and should be further categorized into single field optimized or multifield optimized (SFO or MFO-IMPT). In SFO, inverse planning is employed to optimize each individual beam to conform to the entire target volume while minimizing dose outside. In MFO-IMPT there is simultaneous optimization of all beamlets of all incident beams to deliver the homogeneous prescription dose to the target while limiting the dose to critical volumes of normal tissues to within tolerance levels. For highly complex target shapes and anatomic geometries, MFO-IMPT frequently allows for the optimal balancing of tumor coverage and normal tissue sparing.

Because protons, unlike photons, have a finite range and sharp distal fall-off, they are vulnerable to source uncertainty that may compromise target coverage and normal tissue sparing. Such uncertainties include approximations in converting CT numbers to stopping power ratios for computing dose, variations in daily patient setup, anatomic changes, etc. Each must be carefully accounted for in treatment planning and delivery. IMPT, because of the highly complex dose distributions of its individual fields that fit like a jigsaw puzzle to produce the desired dose distribution, is known to be more vulnerable to such uncertainties than PSPT or SFO.2,3 Great strides are being made in reducing the uncertainties associated with IMPT by incorporating uncertainties in the optimization of treatment plans and evaluating the potential impact of uncertainties on dose distributions.4 For IMPT, at a minimum, robustness (resilience) of dose distributions in the face of uncertainties should be evaluated. This is achieved by evaluating dose distributions under a large number of scenarios in which anatomy position and proton ranges are altered and dose distributions generated. The worst-case scenarios for both adequacy of tumor coverage and normal tissue sparing are then evaluated.5 Research is also ongoing to develop “robust optimization” techniques to minimize the sensitivity of IMPT to uncertainties.6 In robust optimization, beamlet intensities of all IMPT beams are optimized in such a way that the resulting dose distribution meets the specified tumor coverage and normal tissue sparing criteria in the face of all uncertainty scenarios simultaneously. Robustly optimized IMPT has been shown to make dose distributions not only more robust, but more homogeneous and conformal compared with the conventional IMPT optimization.2,3,7

Reduction in uncertainties is also being achieved through the increasing use of volumetric imaging in treatment rooms that allows for more accurate image-guided setups, the use of dual-energy CT for characterizing tissues, and Monte Carlo techniques for calculation of proton dose distributions. Other areas of investigation to reduce uncertainties in proton therapy are PET and prompt gamma imaging (PGI) for the accurate determination of range of protons in vivo.8 Protons undergo nuclear reactions as they traverse the body, producing nuclear isotopes that are positron or gamma emitters. Positron emission may allow for PET imaging, although ideally this would be done while the patient remains on the treatment table rather than in a separate room.9,10 PGI can provide real-time information on proton dose deposition as the patient is being treated and multiple techniques are being explored.11 Most effort so far has been focused on the development of “Compton cameras,” which use multiple gamma ray detectors to measure energy deposited and the point of interaction. Compton cameras are large, highly complex and expensive devices and have potential limitations such as low coincidence efficiency, high detector load, etc.12 A novel promising approach for PGI is the so-called prompt gamma timing, which uses a single compact detector. It measures the gamma rays emitted as protons travel from entrance into the body to the end of their range. Since the velocity of protons is known, the difference in time from entrance to the detection of gamma ray yields the position of point of emission. While techniques such as PET and PGI are promising, it is important to note that they are still in developmental stages and not ready for routine clinical use. Moreover, the magnitude of benefits they will offer, in terms of margin reduction, is uncertain, and complementary techniques such as image guidance will still be required.

Compared with the development of IMRT, which started in the 1990s at multiple centers, the development of IMPT lies on “the learning curve” phase, and it is likely that further improvements will be realized in the coming years.

Improving Our Understanding of the Biology of Gliomas

To outsiders, the field of radiation oncology may be viewed as a specialty driven only by technology, moving from one advance to the next. Indeed, our technology has and continues to evolve and improve. As our collective understanding of the molecular makeup of tumors grows, radiation practitioners may be able to better select which patients are the best candidates for advanced therapies, including IMPT.

Radiation therapy plays an integral role in the treatment of gliomas. As survival rates increase, however, so does the potential impact of radiation-induced adverse effects, including cognitive dysfunction. For World Health Organization (WHO) grade II gliomas, combined modality therapy has contributed to improved survival rates, and early radiation therapy is associated with prolonged progression-free survival.13 Despite the clear benefit of radiotherapy, the timing of radiotherapy—whether delivered as adjuvant or salvage—remains controversial. The existing controversy centers on the negative effects of radiation on cognitive function and quality of life, which are of special importance in a patient population with relatively young median age at diagnosis and a long life expectancy. For patients with WHO grade III or IV tumors, adjuvant radiation therapy is considered standard.

Mutational profiling now allows for the prediction of favorable outcomes for subsets of patients. Increasingly patients with gliomas are broadly divided into those with or without mutations of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) accompanied by a histologic descriptor, with a decreased emphasis on the importance of grade. Perhaps the most notable finding is that patients with grade III gliomas harboring an IDH mutation have favorable outcomes similar to those seen for patients with grade II tumors, with numerous patients achieving long-term survival.14–16 Conversely, patients without IDH mutations may experience more rapid disease progresssion, similar to that seen with WHO grade IV glioblastoma.

For patients with favorable risk disease, the early utilization of radiation therapy will probably contribute to improved progression-free survival; however, based on historical outcomes following photon therapy practitioners or patients may choose to delay radiation therapy based on concerns for radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction, despite documented improvements in disease control. For more aggressive lesions, including tumors historically classified as WHO grade III or glioblastoma, upfront adjuvant radiation therapy is routinely indicated given the typical early recurrence. As described above, the physical benefits of proton therapy allow for superior sparing of normal tissue compared with advanced photon techniques. This sparing may benefit both patients with more indolent tumors and those with higher-grade disease in terms of cognitive preservation. Moreover, for high-grade lesions such as glioblastoma, there is ongoing debate regarding the potential for dose-escalated radiation therapy to improve outcomes. Techniques such as IMPT may be optimally suited to accomplish this.

Potential to Improve Clinical Outcomes: Normal Tissue Toxicity and Disease Control

Despite the efficacy of radiation therapy in the treatment of CNS tumors, substantial concerns exist regarding radiation adverse effects. Concerns regarding long-term radiation effects, including vascular damage, endocrine insufficiencies, and secondary malignancies, are often voiced. The potential for progressive cognitive decline following brain radiation remains the paramount concern for both patients and practitioners. Radiation-induced cognitive impairment is known to occur in up to 50%–90% of adult brain tumor patients after radiation therapy.17–19 Adults who receive radiotherapy for CNS tumors face significant effects on quality of life, with the most commonly reported symptoms being fatigue, changes in mood, and cognitive dysfunction.

Historically, the overwhelming majority of radiation treatments have been delivered using photon-based techniques. Douw et al retrospectively evaluated patients with low-grade gliomas treated with or without radiotherapy and found radiotherapy use to be associated with impaired attentional functioning and executive function.20 Additional data in low-grade glioma patients also suggest that the amount of brain exposed to radiation as well as the dose of radiation has a significant impact on cognitive function and quality of life.21–23 Gondi et al prospectively evaluated the effects of radiation on cognitive function in adult patients with low-grade brain tumors treated with advanced photon radiation techniques, including IMRT. The trial included both baseline and post-radiotherapy assessments utilizing formal neurocognitive tests. Exposure of the bilateral hippocampi to doses as low as 7.3 Gy was associated with long-term memory impairment.24

It is predicted, but not proven, that reducing or eliminating radiation dose to sensitive structures such as the hippocampus should translate into improved cognitive outcomes. The hypothesis of memory-specific hippocampal radiation sensitivity is currently being tested in the setting of whole-brain radiotherapy either therapeutically or prophylactically through the ongoing US-based NRG cooperative group trials CC001 and CC003 (NCT02360215 and NCT02635009, respectively). Other factors, such as volume of normal brain parenchyma irradiated, may also negatively impact other sensitive cognitive domains. The use of IMPT for gliomas, both high and low grade, provides a model to test neuro-anatomic radiation sensitivity given the capacity of IMPT to deliver zero dose to areas of normal brain parenchyma that would otherwise receive low- or modest-dose irradiation using photon radiation techniques such as IMRT. This will ideally be evaluated through new clinical protocols being developed through the NRG designed to evaluate the benefits of proton therapy in comparison to IMRT as it relates to cognitive function in patients with IDH mutant gliomas.

In addition, proton therapy has been shown to enable clinically significant radiotherapy dose escalation close to critical structures. Clival chordoma, for example, requires escalation of radiotherapy dose above the tolerance of adjacent normal tissues such as brainstem, optic nerves, and temporal lobes. Proton therapy, particularly IMPT, is ideally suited for this purpose.25 Emerging data have suggested that escalation of radiotherapy dose and dose-per-fraction in the setting of concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide may improve therapeutic efficacy in the setting of newly diagnosed glioblastoma.26 This hypothesis is currently being tested in NRG BN001 (NCT02179086). As a secondary objective, this trial will also seek to determine whether the use of proton therapy, relative to IMRT, may more effectively and/or safely achieve radiotherapy dose escalation for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

Current Clinical Data

The levels of evidence for clinical studies range from retrospective studies of heterogeneously treated patients to large randomized studies comparing select treatment regimens between balanced groups. For proton therapy in general, very few high quality clinical trials exist. Justification of proton therapy is questioned due to lack of clinical data and the expense of proton therapy.

As the number of proton centers expands, the debate heightens. However, it should be noted that proton therapy suffers from a lack of technology availability, which is especially true for IMPT. Photon machines vastly outnumber proton units. This imbalance inherently limits the number of patients who can be treated with protons. With a small number of patients treated and the extended time necessary for the maturation of clinical data, it will be some time before definitive evidence is produced. Perhaps equally as important, in the limited number of centers that have been in operation for at least 10 years, PSPT has been the dominant, or only, modality. As described above, PSPT is a first-generation proton therapy technique, and the normal tissue sparing and conformality are inferior to IMPT.

While IMPT is arguably the most advanced and newest radiation modality, clinical data for outcomes achieved with PSPT are also available and informative. Investigators from the Massachusetts General Hospital first utilized mixed photon/proton treatments for dose-escalation studies including patients with grades II and III gliomas.27 Disease control rates were acceptable with no advantage associated with dose-escalated therapy, as has been seen in trials using photon therapy. Proton radiotherapy has been previously demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of high-grade gliomas.28–30 Investigators from Japan employed hyperfractionated photon treatments with a proton therapy boost for glioblastoma in a phase I/II trial producing encouraging survival rates.31 Prior to this study, the group at Massachusetts General Hospital had also explored accelerated combined photon/proton therapy for glioblastoma. Here again, survival rates were impressive, albeit with substantially higher rates of normal tissue toxicity which are not entirely unexpected.32

In terms of the ability of protons to preserve cognitive function for patients with gliomas, the best evidence comes from a recent study from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Shih et al reported results of a prospective trial using PSPT, which enrolled patients with WHO grade II gliomas and assessed cognitive function and quality of life following proton therapy. Twenty patients, all with supratentorial tumors, were enrolled. With a median follow-up of 5.1 years, compared with baseline, measures of cognitive function were stable to improved.33

For IMPT specifically, investigators from the University of Heidelberg, which employs scanning-beam proton delivery technology, have also reported initially on 19 patients treated for low-grade gliomas. Similar to photon-based treatments, their initial results suggest high rates of tumor control and acceptable toxicity rates.34

In addition to adult patients, pediatric patients are expected to benefit from IMPT, perhaps even to a greater extent. For pediatric patients, vulnerability to radiation-induced adverse effects is thought to be higher, perhaps due to the fact that the brain is not yet fully developed. Investigators from Loma Linda, one of the first operational proton centers, have documented favorable outcomes in juvenile patients treated with PSPT for low-grade astrocytomas.35 Investigators from Massachusetts General Hospital have also reported excellent disease control rates with low rates of toxicity.36 While, as in adults, no clinical data have definitely proven the superiority of proton therapy, evidence is beginning to emerge suggesting a potential benefit in terms of cognitive preservation.37 However, further prospective study is needed.

Lastly, it is also worth noting that proton therapy may have substantial benefits for the treatment of the spine, either as part of comprehensive craniospinal radiation or for localized spinal tumors.38 Benefits include not only sparing anterior structures such as heart, bowel, and esophagus, but for adults, sparing bone marrow within the vertebral bodies. Combined there is evidence that proton therapy reduces clinical toxicities such as nausea and esophagitis while contributing to improved hematologic profiles.39,40

The “Biology” of Proton Beams

While we continue to follow the refinements in our understanding of the molecular makeup of gliomas and other tumor types, the field of radiation oncology must also further understand and utilize the unique biologic aspects of proton therapy itself. It is increasingly realized that a substantial source of uncertainty in proton therapy (both PSPT and IMPT) is the current practice of using a constant relative biologic effectiveness (RBE) value of 1.1. RBE describes how much more or less effective a radiation type is in comparison to a reference photon radiation. It is well known that, on average, protons are roughly 10% more effective than photons in terms of inducing cell kill in cancer cell lines. It is also assumed that protons may be 10% more likely to damage normal tissues in target regions. To account for this, the physical dose delivered with protons is reduced to make it equivalent to photons. However, RBE is a very complex function of dose, LET (which is a function of residual range of protons in the body), tissue or cell type, endpoint, etc. While there is long experience with the use of an RBE of 1.1, there is growing concern that as novel techniques are developed and as proton therapy is applied to wider range of diseases, especially at high doses, there may be some unforeseen treatment responses. Our knowledge of the physical properties of protons tells us that LET increases greatly at the end of a proton beam’s range, ie, at and points beyond the Bragg peak, where essentially all protons come to an abrupt stop, imparting energy deposition in this area. This high rate of energy deposition per unit distance traveled by protons translates into a higher RBE or greater biologic effectiveness in these regions, a fact that is well documented in laboratory studies. Among clinicians there has been debate as to the relevance of such laboratory-based studies, with many citing a lack of evidence in patients that the RBE may be higher than 1.1. However, increasingly evidence is arising, especially for pediatric patients who are highly sensitive to radiation, that higher rates of normal tissue injury, as measured by MRI changes post radiation, have been found in patients treated with proton therapy.41 Importantly for these vulnerable patients, it has been shown that physical dose as well as clinical factors such as young age may predispose to brainstem damage.42 However, evidence for an increased incidence with higher LET is emerging as well.43

Typically with proton therapy delivery techniques, including PSPT and SFO, such highly biologically effective regions are essentially always outside the target volume, within normal tissues. Currently practitioners simplistically account for this by attempting to avoid placing such regions in sensitive normal tissues such as the optic chiasm. However, with MFO-IMPT there is no reason that such highly effective regions cannot be placed within the tumor volume, which would effectively allow for some component of dose escalation and improved normal tissue sparing. While this sounds simplistic enough, a substantial amount of work remains in terms of understanding how RBE varies across a proton beam and developing the capacity to optimize this in the radiation treatment planning system. The benefits of such optimization strategies may be magnified if we also incorporate our growing knowledge of how the genomic makeup of tumors impacts their response to proton therapy. For example, comparing the response of a panel of lung cancer cell lines to protons versus photons, Liu and colleagues found a substantial variation with RBE values ranging from less than 1 to greater than 1.7.44 A clear understanding of the genomic profiles which render tumors more sensitive to particle therapy would clearly allow for the selection of patients expected to benefit the most from protons.

Future Directions

In clinical practice, for the treatment of gliomas, in the vast majority of cases, radiation is used with definitive intent. At face value, comparing the cost for a course of therapy, protons are in fact more expensive than photons. However, comparisons should also be made to the cost to the patient in terms of side effects as well as costs relative to agents used without curative intent. It is well established that radiation exposure to normal tissues exerts negative effects on cognition and quality of life for brain tumor patients. The first principles of radiation oncology call for treating the tumor to the prescribed dose while sparing normal tissues, all in an effort to minimize such side effects. If protons are more effective in achieving this goal, the “cost” to the patient, in terms of quality of life lost, should be considered. A course of radiation therapy, be it photons or protons, used with definitive intent is also typically much lower than newer biologic agents which may only delay disease progression by weeks to months at a significant cost. Indeed, among cancer treatments, radiation has and continues to be one of the most efficacious and cost-effective modalities.

Regardless of such arguments, the field has been called upon to generate proof that proton therapy is in fact superior to photon therapy. In the history of radiation oncology, as photon technologies have advanced—for example, 3D conformal radiation versus IMRT—similarly comparative trials have generally not been conducted or requested. That said, proton therapy is a different form of radiation, and the collective community has called for better evidence. In order to generate such evidence, there must be facilities capable of delivering high quality proton therapy, particularly IMPT. Moreover, special care must be taken in designing high quality comparative clinical trials, ensuring that the most advanced technologies are compared in an appropriately selected patient population.

There also remains great potential for the technologies used to deliver proton therapy as well as image-guidance technologies to improve outcomes. Treatment planning systems continue to improve, and the majority are now routinely incorporating features such as robust optimization. This, combined with small spot sizes that reduce side scatter, will improve normal tissue sparing seen with proton therapy while making target coverage robust and potentially allowing for dose escalation. For image guidance, the field of proton therapy has lagged behind photon-based therapies. Features such as cone beam CT and CT on rails are now commonplace for photon-based machines. For new proton centers, such features are incorporated on essentially all new projects. However, in order to maximize the potential benefits of particle therapy, practitioners using proton therapy must look ahead and not only ensure that image guidance matches that of photons, but exceeds photon therapy techniques. Currently MR-guided photon therapy is gaining in popularity, although it is still available at only a select number of centers. Consideration should be given to including this in particle therapy, despite the technical challenges. Beyond techniques used for photon-based therapies, unique image-guidance techniques may become commonplace for proton therapy. These include the use of tools such as PGI and in-beam PET. These techniques have the potential to identify, with high precision, where the proton beam stops within a patient. If successful, such techniques would allow for the further reduction in margins, which are typically added to target volumes to account for uncertainties in where the proton beam stops. The reduction in such margins is of the utmost importance in that it will further improve normal tissue sparing.

As a field, in order to maximize the potential of our therapies, radiation oncology must incorporate a detailed understanding of the biologic mechanisms at play. This includes, of course, using prognostic information such as IDH status to help identify groups of patients where long-term survival is expected and the low-dose sparing afforded by IMPT should translate into reduced long-term adverse effects. At the same time, by identifying patients at high risk for disease progression, the conformality afforded by IMPT may both reduce the potential for adverse effects and facilitate dose escalation to improve local control. Increasingly, it is recognized that radiation therapy when combined with immunotherapy may have “off target” effects with the radiation-induced death of cancer cells allowing for antigen presentation and a more robust immune response. Whether protons are more “immunogenic” than photons remains a subject under investigation. However, it is likely that by simply sparing normal tissues to a greater extent, protons may have less detrimental effects on normal lymphocytes (which are exquisitely sensitive to ionizing radiation) than photons do. Lastly, it is important to reiterate that there remain substantial uncertainties regarding the biologic effectiveness of proton beams themselves. However, if a clear understanding of the relation of biologic effect with physical factors such as LET can be developed, this can be exploited, using IMPT, to expand the therapeutic index of proton therapy.

In summary, it is safe to say that the field of proton and particle therapy is still maturing. While proton therapy has been delivered in a select number of centers for decades, the treatment techniques utilized have been suboptimal. In recent years proton delivery techniques, which include IMPT, have improved dramatically. These technological advances come as our understanding of the underlying biology of gliomas is changing rapidly. So too is our understanding of the unique biologic aspects of particle therapy itself. The challenge for practitioners is now to integrate the technology of protons with the biology of the disease and the proton beam. As the number of treatment centers capable of IMPT increases, so will clinical data regarding the benefits of this technology. However, it is important for practitioners and the field in general to design the appropriate trials to demonstrate such benefits.

Funding

The work described was supported in part by Award Number U19 CA021239 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Moteabbed M, Yock TI, Depauw N, Madden TM, Kooy HM, Paganetti H. Impact of spot size and beam-shaping devices on the treatment plan quality for pencil beam scanning proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(1):190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu W, Frank SJ, Li X, Li Y, Zhu RX, Mohan R. PTV-based IMPT optimization incorporating planning risk volumes vs robust optimization. Med Phys. 2013;40(2):021709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu W, Zhang X, Li Y, Mohan R. Robust optimization of intensity modulated proton therapy. Med Phys. 2012;39(2):1079–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fredriksson A. A characterization of robust radiation therapy treatment planning methods—from expected value to worst case optimization. Med Phys. 2012;39(8):5169–5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fredriksson A, Bokrantz R. A critical evaluation of worst case optimization methods for robust intensity-modulated proton therapy planning. Med Phys. 2014;41(8):081701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen W, Unkelbach J, Trofimov A, et al. Including robustness in multi-criteria optimization for intensity-modulated proton therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57(3):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu W, Mohan R, Park P, et al. Dosimetric benefits of robust treatment planning for intensity modulated proton therapy for base-of-skull cancers. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2014;4(6):384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kraan AC. Range verification methods in particle therapy: underlying physics and monte carlo modeling. Front Oncol. 2015;5:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dendooven P, Buitenhuis HJ, Diblen F, et al. Short-lived positron emitters in beam-on PET imaging during proton therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(23):8923–8947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shao Y, Sun X, Lou K, et al. In-beam PET imaging for on-line adaptive proton therapy: an initial phantom study. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59(13):3373–3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richter C, Pausch G, Barczyk S, et al. First clinical application of a prompt gamma based in vivo proton range verification system. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118(2):232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hueso-Gonzalez F, Fiedler F, Golnik C, et al. Compton camera and prompt gamma ray timing: two methods for in vivo range assessment in proton therapy. Front Oncol. 2016;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O, et al. ; EORTC Radiotherapy and Brain Tumor Groups and the UK Medical Research Council. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9490):985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olar A, Wani KM, Alfaro-Munoz KD, et al. IDH mutation status and role of WHO grade and mitotic index in overall survival in grade II-III diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(4):585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, et al. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, et al. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2499–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meyers CA, Smith JA, Bezjak A, et al. Neurocognitive function and progression in patients with brain metastases treated with whole-brain radiation and motexafin gadolinium: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crossen JR, Garwood D, Glatstein E, Neuwelt EA. Neurobehavioral sequelae of cranial irradiation in adults: a review of radiation-induced encephalopathy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(3):627–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Armstrong CL, Shera DM, Lustig RA, Phillips PC. Phase measurement of cognitive impairment specific to radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(3):e319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Douw L, Klein M, Fagel SS, et al. Cognitive and radiological effects of radiotherapy in patients with low-grade glioma: long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(9):810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown PD, Buckner JC, Uhm JH, Shaw EG. The neurocognitive effects of radiation in adult low-grade glioma patients. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5(3):161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laack NN, Brown PD. Cognitive sequelae of brain radiation in adults. Semin Oncol. 2004;31(5):702–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kiebert GM, Curran D, Aaronson NK, et al. Quality of life after radiation therapy of cerebral low-grade gliomas of the adult: results of a randomised phase III trial on dose response (EORTC trial 22844). EORTC Radiotherapy Co-operative Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(12):1902–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gondi V, Hermann BP, Mehta MP, Tome WA. Hippocampal dosimetry predicts neurocognitive function impairment after fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for benign or low-grade adult brain tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(2):348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grosshans DR, Zhu XR, Melancon A, et al. Spot scanning proton therapy for malignancies of the base of skull: treatment planning, acute toxicities, and preliminary clinical outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(3):540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsien CI, Brown D, Normolle D, et al. Concurrent temozolomide and dose-escalated intensity-modulated radiation therapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(1):273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Harsh G, 4th, et al. Dose-escalation with proton/photon irradiation for Daumas-Duport lower-grade glioma: results of an institutional phase I/II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51(1):131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mizumoto M, Tsuboi K, Igaki H, et al. Phase I/II trial of hyperfractionated concomitant boost proton radiotherapy for supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(1):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Combs SE. Radiation therapy. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2009;171:125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Combs SE, Ellerbrock M, Haberer T, et al. Heidelberg Ion Therapy Center (HIT): Initial clinical experience in the first 80 patients. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(7):1132–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mizumoto M, Tsuboi K, Igaki H, et al. Phase I/II trial of hyperfractionated concomitant boost proton radiotherapy for supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(1):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Rabinov JD, et al. Accelerated fractionated proton/photon irradiation to 90 cobalt gray equivalent for glioblastoma multiforme: results of a phase II prospective trial. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(2):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shih HA, Sherman JC, Nachtigall LB, et al. Proton therapy for low-grade gliomas: results from a prospective trial. Cancer. 2015:29237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hauswald H, Rieken S, Ecker S, et al. First experiences in treatment of low-grade glioma grade I and II with proton therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hug EB, Muenter MW, Archambeau JO, et al. Conformal proton radiation therapy for pediatric low-grade astrocytomas. Strahlenther Onkol. 2002;178(1):10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greenberger BA, Pulsifer MB, Ebb DH, et al. Clinical outcomes and late endocrine, neurocognitive, and visual profiles of proton radiation for pediatric low-grade gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89(5):1060–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kahalley LS, Ris MD, Grosshans DR, et al. Comparing intelligence quotient change after treatment with proton versus photon radiation therapy for pediatric brain tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Amsbaugh MJ, Grosshans DR, McAleer MF, et al. Proton therapy for spinal ependymomas: planning, acute toxicities, and preliminary outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):1419–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown AP, Barney CL, Grosshans DR, et al. Proton beam craniospinal irradiation reduces acute toxicity for adults with medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(2):277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barney CL, Brown AP, Grosshans DR, et al. Technique, outcomes, and acute toxicities in adults treated with proton beam craniospinal irradiation. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(2):303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gunther JR, Sato M, Chintagumpala M, et al. Imaging changes in pediatric intracranial ependymoma patients treated with proton beam radiation therapy compared to intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(1):54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Indelicato DJ, Flampouri S, Rotondo RL, et al. Incidence and dosimetric parameters of pediatric brainstem toxicity following proton therapy. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(10):1298–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peeler CR, Mirkovic D, Titt U, et al. Clinical evidence of variable proton biological effectiveness in pediatric patients treated for ependymoma. Radiother Oncol. 2016:001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu Q, Ghosh P, Magpayo N, et al. Lung cancer cell line screen links fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway defects to increased relative biological effectiveness of proton radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(5):1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]