Abstract

Objective:

Sedentary behavior (SB) is associated with poor cognitive performance in the general population. Although people with schizophrenia are highly sedentary and experience marked cognitive impairments, no study has investigated the relationship between SB and cognition in people with schizophrenia.

Methods:

A total of 199 inpatients with schizophrenia (mean [SD] age 44.0 [9.9] years, 61.3% male, mean [SD] illness duration 23.8 [6.5]) and 60 age and sex matched controls were recruited. Sedentary behavior and physical activity (PA) were captured for 7 consecutive days with an accelerometer. Cognitive performance was assessed using the Vienna Test System, and the Grooved Pegboard Test. Multivariate regression analyses adjusting for important confounders including positive and negative symptoms, illness duration, medication, and PA were conducted.

Results:

The 199 patients with schizophrenia engaged in significantly more SB vs controls (581.1 (SD 127.6) vs 336.4 (SD 107.9) min per day, P < .001) and performed worse in all cognitive performance measures (all P < .001). Compared to patients with high levels of SB (n = 89), patients with lower levels of SB (n = 110) had significantly (P < .05) better motor reaction time and cognitive processing. In the fully adjusted multivariate analysis, SB was independently associated with slower motor reaction time (β = .162, P < .05) but not other cognitive outcomes. Lower levels of PA were independently associated with worse attention and processing speed (P < .05).

Conclusion:

Our data suggest that higher levels of sedentary behavior and physical inactivity are independently associated with worse performance across several cognitive domains. Interventions targeting reductions in SB and increased PA should be explored.

Keywords: sedentary behavior, inactivity, cognition, cognitive performance, schizophrenia, psychosis

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 1% with a heterogeneous genetic and neurobiological background that influences early brain development, and is expressed as a combination of psychotic symptoms—such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganization.1 The burgeoning evidence base has established that schizophrenia is associated with considerable cognitive impairment.2 Specifically, research has demonstrated that schizophrenia is associated with deficits across multiple domains including attention, processing speed, working memory, verbal learning and memory, and executive functions.3 Cognitive dysfunction is evident in those with the at risk mental state,4,5 experiencing their first episode6 and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia endure over the course of illness.7 Understanding factors that are associated with cognitive performance are important, because cognitive deficits are associated with increased healthcare costs,8 lower quality of life, and impaired recovery.9 A range of factors have been associated with cognitive performance in schizophrenia including genetic predisposition,10 hypofunction of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors,11 negative symptoms, sociodemographic and illness factors (eg, male gender, illness duration).12 Most recently, novel research has suggested that physical activity appears to be associated with better cognitive performance and in particular attention/concentration.13

Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.14 Physical activity sits on a spectrum, ranging from low intensity physical activity (eg, light walking) to high intensity activity (eg, fast running) and is categorized based on energy expenditure. At the opposite end of the spectrum, is sedentary behavior, which is defined as any waking activity characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents.15 Examples of sedentary behaviors may include prolonged sitting or remaining in reclined posture during the day time. In the general population, there is an increasing evidence base to suggest that sedentary behavior is independent from physical activity associated with worse cognitive performance.16 Higher levels of sedentary behavior are associated with worse cognitive performance across the lifespan including in children17 and older adults.18 A recent systematic review of 8 studies concluded that higher levels of sedentary behavior were associated with worse cognitive function.16

Despite the growing interest in the potential deleterious impact of sedentary behavior in people with schizophrenia, no study has to our knowledge investigated the relationship with cognitive performance. Nonetheless, a recent meta-analysis19 established that people with schizophrenia engage in very high levels of sedentary behavior. To date, only 2 studies20,21 have investigated the relationship between sedentary behavior and health outcomes in people with schizophrenia, and both established a negative relationship with cardiometabolic markers. Although helpful, Stubbs et al20 and Vancampfort et al21 relied upon self-report sedentary behavior (which is prone to bias19) and did not include a control group. Only 5 published studies have utilized objective measures of sedentary behavior in people with schizophrenia,22–26 of which, only one study included a control group,24 and all included modest sample sizes (n < 50). There is also provisional evidence that higher light physical activity may be associated with better cognitive performance.13 It remains unclear if the relationship between physical activity and cognitive performance is independent from sedentary behavior and vice versa. Nonetheless, given the relationship between sedentary behavior and cognition in the general population, the high levels of sedentary behavior and cognitive deficits in people with schizophrenia, research is required to explore if sedentary behavior and low physical activity are associated with cognition in this population. In addition, it is important that research considers if a relationship between sedentary behavior and cognition would also be evident after adjusting for important confounders known to influence both factors such as negative symptoms.25,27

The aims of the current study were to (1) investigate sedentary behavior levels in people with schizophrenia compared to controls using accelerometer, (2) investigate the relationship between sedentary behavior and cognitive performance in people with schizophrenia and compare this to controls, and (3) Explore the possible independent associations between sedentary behavior and low physical activity and cognitive performance in people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Participants

The current study recruited participants from the long stay psychiatric wards at Jianan Mental Hospital, Taiwan. Inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of schizophrenia (according to DSM IV made by an independent psychiatrist), (2) stable and on the same antipsychotic medicine for at least 3 months. Patients who were unable to communicate, walk independently or had any neurological disorders were excluded.

Healthy Control Group.

The healthy control group consisted of age-, gender-, and BMI-matched comparison participants recruited among the staff of 2 hospitals and universities. Eligibility criteria for controls included (1) no present or past history of any mental illness and (2) not taking any psychotropic medication. A total of 60 participants were selected to ensure comparable gender balance, age, and BMI ranges to the schizophrenia group.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jianan Mental Hospital. All participants provided informed written consent.

Measures

Outcome Variable: Cognitive Function Assessments Vienna Test System (VTS).

All participants (including controls) completed the cognitive outcome measures. The VTS is a computerized neurocognitive function assessment consisting of various personality, intelligence, and psychomotor abilities.28 The VTS has been used in previous studies,29,30 including those with schizophrenia31 to determine cognitive performance. Specifically, within the current study, 2 subsets of the VTS were used: the Reaction test (RT) and Cognitrone test (COG). The RT measures the determination of reaction time to visual stimulus of individuals and the test last between 5 and 10min. Participants place their hands on the rest button, and are asked to push it as soon as possible when they detect a visual stimulus. The reaction and motor time is calculated in milliseconds (msec), which is the time between the start of the relevant stimulus and the moment the finger leaves the rest button.

The COG test captures the attention and concentration through the comparison of figures with regard to their congruence on a computer screen. Within the COG test, participants are presented with an abstract figure which they have to match to a model. The variable of the number of reactions made within the total working time of 7min provides information on the respondent’s processing speed.28

Grooved Pegboard Test (GPT).

The GPT is a test of manual dexterity, upper-limb motor speed, hand-eye coordination, and speed of processing and has been widely used in previous research.32–35 The GPT consists of 25 holes with randomly positioned slots. The pegs have a key along one side and must be put in the board in a fixed order and in the correct direction with only one hand being used. Participants are encouraged to perform the task as quickly as possible. Each participant is scored by the total time in seconds from when they starts the task until the last peg is put in place. For the purposes of the current study, each participant was tested once with their dominant and nondominant hand (ie, a total of 2 times) and the average was calculated to give an overall score.

Independent Variable: Sedentary Behavior Time.

Sedentary behavior was captured using the ActiGraph (wActiSleep), a tri-axial accelerometer. The ActiGraph has been validated previously among people with schizophrenia.36–38 The measurement of sedentary behavior with accelerometers is the optimal free living measure in people with schizophrenia, with self-report measures such as the IPAQ lacking accuracy.39 Standardized instructions of wearing an accelerometer were provided by research assistants. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on the wrist of the nondominant hand for 7 consecutive days and to remove it during bathing or water activities. The accelerometers were initialized, downloaded, and analyzed using ActiLife software version 6 (ActiGraph LLC). Sedentary behavior was defined according to the cut-off point outlined by Freedson40 as activities ≦100 counts per minute (cpm), representing a threshold corresponding with sitting, reclining, or lying down. The sedentary behavior time was only measured during the waking day of each individual. The total energy expenditure of physical activity per week was also calculated by the software. Sedentary behavior and total physical activity were categorized into 2 levels by the mean: “low and high” in a binary split at the mean.

Covariates.

A range of sociodemographic information was collected including data on age (<40 or ≥40), sex, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and education (<9 schooling years or ≥9 schooling years). Based on self-report answers, participants were categorized into 2 groups: “yes” (current/former smoker or drinker) and “no” (never). Body weight and height were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). BMI classifications of obesity reflect risks for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases and varies among ethnic groups.41 Therefore, the national criteria of obesity in Taiwan were used to determine weight status (normal/underweight <24, overweight/obesity ≥24).42

Metabolic Syndrome and Associated Metabolic Risk Factors.

Details regarding the metabolic syndrome (MetS) criteria and associated risk factors were collected including waist circumference, systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP), serum triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and fasting glucose (FG). Abnormalities in MetS were classified based on the following criteria: waist circumference ≥90cm in men and ≥80cm in women; SBP/DBP ≥130/85 mmHg; TG ≥150mg/dl; HDL-C <40mg/dl in men and <50mg/dl in women; and FG ≥100mg/dl. We used the number of abnormalities in MetS in the analyses and it requires meeting 3 or more of the five criteria to be diagnosed with MetS.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

All participants completed the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), a tool specifically developed to assess the severity of symptoms and measure general psychopathology among patients with schizophrenia.43 It is a 30-item rating scale, consisting of 3 subscales: 7-item Positive Symptoms, 7-item Negative Symptoms, and 16-item General Psychopathology. For each item, there are 7 rating points with increasing levels of psychopathology severity from 1 (asymptomatic) to 7 (extremely symptomatic). The PANSS score is the sum of ratings across items, with ranging from 7 to 49 for the Positive and Negative Scales and 16 to 112 for the General Psychopathology Scale. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

Medication.

Information regarding antipsychotics medication and sleeping pills use was collected through the hospital records. Antipsychotics medication use was converted into a daily equivalent dosage of chlorpromazine44 and the daily equipotent dosage of Lorazepam were also calculated for each patient according to the defined daily dose (DDD) of WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (http://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/).

Statistical Analyses

Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were performed to compare the percentages or differences between levels of sedentary time in participants with schizophrenia. Differences of cognitive function, sedentary time, and physical activity energy expenditure between participants with and without schizophrenia were examined by independent t-tests. To examine the association of sedentary levels on cognition function, a 2-step forced entry multivariate regression analysis was performed for each cognitive test. In the multivariate linear regression, the dependent variable was sedentary behavior levels and variables entered into the model were demographic variables (age, sex, education), weight status, smoking, alcohol consumption, medications, PANSS, and MetS, followed by physical activity energy expenditure. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics 22 and a 2-tailed P-value less than .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 200 potential inpatients were identified as suitable for the study. Overall, 199 patients with schizophrenia gave informed consent and were recruited with a mean age of 44.0 years (SD 9.9), 61.3% were male with a mean illness duration of 23.8 years (SD 6.5). Sixty age and sex matched controls were also recruited (mean age 41.1 (9.6) years, 56.7% male).

Sedentary Behavior, Clinical, and Cognitive Outcomes in Patients

Patients with schizophrenia were divided into low levels of sedentary behavior (n = 110, <581.1min per day) and high levels of sedentary behavior (n = 89, ≥581.1min per day). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical outcomes for both groups. Briefly, no difference in gender, age, or education was observed, although those who were more sedentary were less likely to smoke (table 1). No difference in psychiatric symptoms, chlorpromazine equivalents or illness duration was noted, although the less sedentary group had been admitted for longer. Patients who were more sedentary had worse motor reaction time and speed processing (P < .05) and engaged in less physical activity.

Table 1.

Characteristic Comparisons of Sedentary Levels in Patients With Schizophrenia

| Variables % or Mean (SD) | Low Sedentary | High Sedentary | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (%) | .322 | ||

| <40 | 59.7 | 40.3 | |

| ≥40 | 52.4 | 47.6 | |

| Sex (%) | .647 | ||

| Female | 53.2 | 46.8 | |

| Male | 56.6 | 43.4 | |

| Education (%) | .973 | ||

| High (≥9 years) | 55.4 | 44.6 | |

| Low (<9 years) | 55.1 | 44.9 | |

| Weight status (%) | .398 | ||

| Normal (BMI < 24) | 52.1 | 47.9 | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 24) | 58.1 | 41.9 | |

| Smoke (%) | .004 | ||

| Never | 46.5 | 53.5 | |

| Yes | 67.1 | 32.9 | |

| Alcohol (%) | .500 | ||

| Never | 54.2 | 45.8 | |

| Yes | 60.6 | 39.4 | |

| No. of meeting MetSa | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.3) | .754 |

| PANSSb | 61.4 (20.1) | 64.9 (20.0) | .209 |

| PANSS_P | 15.2 (6.8) | 15.7 (4.0) | .529 |

| PANSS_N | 16.6 (5.8) | 17.3 (6.6) | .459 |

| PANSS_G | 29.6 (10.4) | 32.0 (11.0) | .114 |

| Chlorpromazine equivalent doses (mg/d) | 859.4 (856.0) | 833.1 (688.6) | .815 |

| Lorazepam equivalent doses (mg/d) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.1) | .886 |

| Time since illness onset (year) | 23.2 (7.1) | 24.5 (5.8) | .193 |

| Duration of hospitalization (month) | 16.1 (19.5) | 11.5 (13.1) | .047 |

| Cognitive function | |||

| RTc _Reaction (msec) | 669.5 (532.2) | 652.3 (410.0) | .803 |

| RTc _Motor (msec) | 355.2 (170.8) | 421.3 (252.7) | .037 |

| COGd | 176.9 (95.1) | 165.8 (107.1) | .442 |

| GPTe (sec) | 131.6 (44.1) | 145.4 (46.7) | .034 |

| Physical activity (Kcal) | 644.3 (384.3) | 471.4 (294.4) | <.001 |

Note: Sedentary behavior total time was split at the mean to develop low levels of sedentary behavior (n = 110, <581.1min per day) and high levels of sedentary behavior (n = 89, ≥581.1min per day).

aMetabolic syndrome.

bPositive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

cReaction time.

dCognitrone: number of total reactions.

eGrooved Pegboard Test.

Sedentary Behavior and Cognition in Patients and Controls

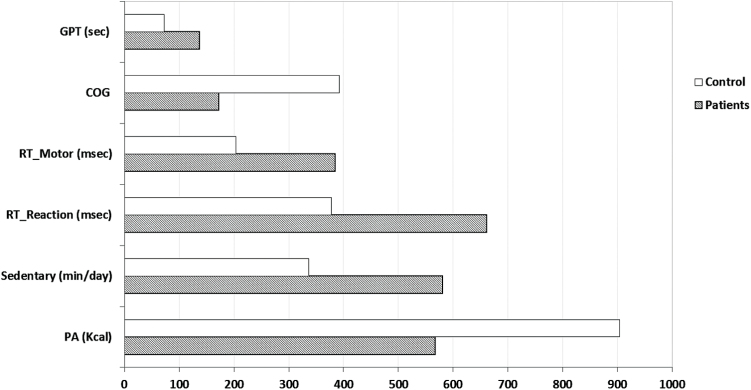

Patients with schizophrenia engaged in significantly more sedentary behavior vs controls (581.1min per day vs 336.4min per day, P < .001) equating to a mean difference of 244.6min per day or 4h and 7min per day. Patients with schizophrenia also engaged in less total physical activity (567.0 vs 904.1 Kcal per day, P < .001; mean difference 337.1) and had worse cognitive performance on all measures vs controls (all P < .001) (figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Cognition performance, sedentary time, and physical activity in participants with and without schizophrenia. All P < .001. GPT, Grooved Pegboard Test (total time); COG, Cognitrone test (number of total reactions); RT, Reaction time test (total time); Sedentary, sedentary time (time of sitting, reclining, or lying down per day excluding sleep); PA, physical activity (total energy expenditure of physical activity per week).

Exploring the Independent Relationships Between Sedentary Behavior and Low Physical Activity and Cognition

The multivariate associations between sedentary behavior and other outcomes with cognitive performance in the adjusted model with and without adjusting for physical activity are outlined in tables 2 and 3, respectively. Patients with schizophrenia who engaged in higher levels of sedentary behavior had a slower motor reaction time (β = .175, P = .026), while no relationship was observed with the Cognitrone or Grooved Pegboard Test. After adjusting for physical activity, the relationship between higher levels of sedentary behavior was independently associated with slower motor reaction times (β = .162, P = .042). Lower levels of physical activity were independently associated with worse attention and concentration (Cognitrone scores) (β = −.222, P = .008) and poorer processing speed and manual dexterity (GPT scores, β = .309, P < .001) in the fully adjusted model.

Table 2.

Multivariable Linear Regressions of Cognitive Function in People With Schizophrenia (Without Adjusting Physical Activity)

| Variables | COG | GPT | RT-Reaction | RT-Motor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | |

| 18.6 | 15.7 | 15.8 | 14.0 | |||||||||

| Age (≥40)a | −.235 | .002 | .201 | .009 | .083 | .277 | .121 | .120 | ||||

| Sex (Male)a | .108 | .248 | −.108 | .254 | −.247 | .010 | −.184 | .056 | ||||

| Education (low)a | −.029 | .689 | .076 | .308 | .045 | .548 | −.002 | .982 | ||||

| Weight status (obese)a | .180 | .027 | −.096 | .244 | −.131 | .111 | −.054 | .513 | ||||

| Smoke (yes)a | .031 | .733 | −.094 | .305 | .024 | .797 | .064 | .488 | ||||

| Alcohol (yes)a | −.091 | .247 | .143 | .074 | .036 | .650 | −.122 | .129 | ||||

| MetS | −.009 | .907 | .116 | .151 | .135 | .094 | .001 | .994 | ||||

| PANSS | −.223 | .010 | .231 | .008 | .366 | <.001 | .228 | .010 | ||||

| Chlorpromazine equivalent doses | .152 | .044 | .147 | .056 | .001 | .992 | −.134 | .085 | ||||

| Lorazepam equivalent doses | −.143 | .062 | −.043 | .578 | .068 | .382 | .074 | .345 | ||||

| Time since illness onset (year) | .038 | .613 | −.001 | .993 | −.045 | .559 | −.134 | .085 | ||||

| Duration of hospitalization (month) | −.025 | .739 | −.060 | .436 | .020 | .795 | .037 | .633 | ||||

| Physical activity (low)a | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sedentary (high)a | −.010 | .897 | .062 | .424 | −.031 | .690 | .175 | .026 | ||||

Note: Bold values are statistically significant.

aDummy variable.

Table 3.

Multivariable Linear Regressions of Cognitive Function in People With Schizophrenia (Adjusting Physical Activity)

| Variables | COG | GPT | RT-Reaction | RT-Motor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | R 2 | Beta | P Value | |

| 22.1 | 22.5 | 17.1 | 14.5 | |||||||||

| Age (≥40)a | −.192 | .012 | .140 | .065 | .057 | .468 | .104 | .190 | ||||

| Sex (Male)a | .056 | .551 | −.036 | .700 | −.215 | .027 | −.165 | .094 | ||||

| Education (low)a | −.030 | .680 | .076 | .288 | .045 | .544 | −.002 | .984 | ||||

| Weight status (obese)a | .120 | .146 | −.013 | .877 | −.095 | .266 | −.032 | .714 | ||||

| Smoke (yes)a | .023 | .795 | −.083 | .345 | .028 | .756 | .067 | .469 | ||||

| Alcohol (Yes)a | −.098 | .203 | .153 | .047 | .040 | .608 | −.119 | .138 | ||||

| MetS | −.008 | .920 | .114 | .143 | .134 | .094 | .001 | .999 | ||||

| PANSS | −.175 | .043 | .164 | .057 | .336 | <.001 | .209 | .021 | ||||

| Chlorpromazine equivalent doses | .148 | .046 | .153 | .039 | .003 | .964 | −.132 | .089 | ||||

| Lorazepam equivalent doses | −.167 | .028 | −.010 | .891 | .083 | .290 | .083 | .294 | ||||

| Time since illness onset (year) | .073 | . 332 | −.049 | .512 | −.066 | .394 | −.147 | .063 | ||||

| Duration of hospitalization (month) | −.015 | .840 | −.074 | .317 | .014 | .857 | .033 | .669 | ||||

| Physical activity (low)a | −.222 | .008 | .309 | <.001 | .136 | .111 | .084 | .330 | ||||

| Sedentary (high)a | .025 | .745 | .014 | .854 | −.052 | .505 | .162 | .042 | ||||

Note: Bold values are statistically significant.

aDummy variable.

Discussion

The current study is the largest to investigate objective sedentary behavior in people with schizophrenia and controls and has several novel findings. First, our data suggest that sedentary behavior is associated with worse motor reaction time, independent from multiple confounders. Second, our data show that among patients, those with higher levels of sedentary behavior appear to have worse speed processing and motor reaction times compared with those who are less sedentary. Third, lower levels of physical activity appear to be independently associated with poorer processing speed, attention, and dexterity. Fourth, our data are the first to suggest that sedentary behavior and physical inactivity (less physical activity) are independently associated with neurocognition. Finally, our data also confirm that people with schizophrenia engage in significantly more sedentary behavior (mean difference 4h and 7min per day) and less total physical activity than age and sex matched controls.

The potential mechanisms through which sedentary behavior may influence cognitive performance among people with schizophrenia are yet to be elucidated. One potential explanation is that the high levels of obesity and glucose/lipid metabolism alterations in people with schizophrenia,45,46 which are known to influence cognition in the general population through atrophy in several brain regions and hippocampal dysfunction,47 could play an integral role. Excess sedentary behavior in the general population is known to increase the risk of cardiometabolic disease48 with around an extra hour a day being associated with a 22% and 39% increased risk of diabetes and MetS, respectively.49 Some preliminary work has demonstrated that excess self-reported sedentary behavior is associated with elevated C reactive protein20 and MetS21 in people with schizophrenia. There is also emerging evidence that obesity is associated with worse cognitive performance among people with schizophrenia.50,51 Therefore, the hazards of obesity and metabolic alterations may be influenced by sedentary behavior, and extend beyond contributing to the excess mortality52 and also negatively influence cognition. An alternative explanation might also be that cognitive impairment may exacerbate negative symptoms (such as avolition) and reduce social functioning, both of which would increases the likelihood of sedentary behavior. Clearly, given the cross sectional nature of our work, more longitudinal research is required to disentangle these potential relationships and confirm the directionality to test these hypotheses.

The objective sedentary behavior data from the current study includes data on more people with schizophrenia than all of the previous 5 published studies pooled in a prior meta-analysis.20 Our results found that that people with schizophrenia were sedentary for on average 581.1min per day, which is comparable with the recent meta-analysis in this patient group (599min per day).19 It is worth noting this amount of sedentary behavior is among the highest reported in any clinical population. The difference between patients with schizophrenia and controls in sedentary behavior was very high (over 4h) and is clearly concerning, not only for the potential relationship with poor cognition, but also due to the robust evidence in the general population that sedentary behavior is associated with cardiovascular disease and associated mortality.48 Previously, a study found that people with schizophrenia that spent 1.5h of self-report sedentary behavior more than another group of patients, was associated with an increased level of C reactive protein (>5.0mg/μl). Our data also suggest that the difference in sedentary behavior between low and high sedentary patients (mean difference =196.4min per day) is associated with reduced cognitive function. An important area for future research is to explore with longitudinal/interventional data if reducing sedentary behavior in patients can improve cognition and indeed the inflammatory profile of people with schizophrenia.

Interestingly, we found that physical inactivity (lower levels of physical activity) is independently associated with worse processing speed and attention among our population with established psychosis. Although the relationship between physical activity and cognition is reasonably well established in the general population,53 our data offer further evidence of the potential benefits of physical activity in people with schizophrenia. The relationship between low physical activity and these cognitive performance measures appears independent of sedentary behavior and other important confounders (eg, positive and negative symptoms, antipsychotic medication) and is the first data to demonstrate this independent relationship. There have been pressing calls for members of the multidisciplinary team to reduce sedentary behavior in people with psychosis due to the potential deleterious impact on cardiometabolic health54 and an important future research question is whether replacing sedentary time with physical activity can improve health outcomes. There is an emerging evidence base from RCTs that aerobic exercise can improve cognition,55 as to whether specifically targeting reductions in sedentary behavior can prevent decline in cognitive performance and/or improve cognition is an important area for future research. The potential mechanism by which physical activity could improve cognitive performance may be related to hippocampal neurogenesis, although the literature is equivocal among people with schizophrenia to date.56 Regardless, given the established benefits of physical activity on various health dimensions among people with schizophrenia,57 and relatively low levels of activity,58 physical activity should be encouraged among this group.

Although our data are the largest study investigating objective sedentary behavior and include multiple novel results, some limitations exist. The primary limitation is that the data is cross sectional and therefore it is important that future longitudinal work disentangles the relationships we observed. Second, the study included people with established psychosis who were inpatients which limits the generalizability. Future research in the earlier stages of illness is required to see if similar relationships exist. In particular, interventions targeting reductions in sedentary behavior in those with first episode psychosis should consider if cognitive performance subsequently improves. There is some provisional evidence that physical exercise can improve cognition in people with first episode psychosis59 and whether or not reducing sedentary behavior in this group can improve cognition is an important future research question. Third, the variance explored by our models was relatively modest, which does suggest that other factors not accounted for in our study may also account for the relationships we observed. Finally, we did not conduct any additional post hoc tests to adjust for multiple testing; therefore there is possibility of type I errors in the data. Clearly, future longitudinal research is required to confirm/refute our exploratory data.

In conclusion, the largest study using objective measures of sedentary behavior in schizophrenia to date, suggests that sedentary behavior may be related to reduced motor reaction time. Moreover, patients with higher levels of sedentary behavior appear to have worse cognitive performance than those engaging in less sedentary behavior. Higher levels of physical activity appear to be associated with better cognitive performance independent of sedentary behavior and multiple other factors. Clearly, future longitudinal data are required to confirm/refute our findings. Nonetheless, given the deleterious impact of sedentary behavior on multiple health outcomes, interventions specifically targeting reducing sedentary behavior are required among this highly sedentary population.

Funding

This work was in part supported by the National Taiwan University of Sport and the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (104-2410-H-018-028). B.S. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author[s] and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM, et al. Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fioravanti M, Bianchi V, Cinti ME. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an updated metanalysis of the scientific evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Cognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hou CL, Xiang YT, Wang ZL, et al. Cognitive functioning in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis, first-degree relatives of patients with psychosis and patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;174:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Paula AL, Hallak JE, Maia-de-Oliveira JP, Bressan RA, Machado-de-Sousa JP. Cognition in at-risk mental states for psychosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Caldiroli A, Buoli M, Serati M, Cahn W, Altamura AC. General and social cognition in remitted first-episode schizophrenia patients: a comparative study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rajji TK, Mulsant BH. Nature and course of cognitive function in late-life schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:122–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel A, Everitt B, Knapp M, et al. Schizophrenia patients with cognitive deficits: factors associated with costs. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:776–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aquila R, Citrome L. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: the great unmet need. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(suppl 1):35–39; quiz 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bortolato B, Miskowiak KW, Köhler CA, Vieta E, Carvalho AF. Cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:3111–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwata Y, Nakajima S, Suzuki T, et al. Effects of glutamate positive modulators on cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1151–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Talreja BT, Shah S, Kataria L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia and its association with socio-demographics factors. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen LJ, Steptoe A, Chung MS, Ku PW. Association between actigraphy-derived physical activity and cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2016;46:2375–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974). 1985;100:126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. Letter to the Editor: Standardized use of the terms ‘sedentary’ and ‘sedentary behaviours’. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Falck RS, Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T. What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2016. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aggio D, Smith L, Fisher A, Hamer M. Context-specific associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with cognition in children. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:1075–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Steinberg SI, Sammel MD, Harel BT, et al. Exercise, sedentary pastimes, and cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30:290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stubbs B, Williams J, Gaughran F, Craig T. How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;171:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stubbs B, Gardner-Sood P, Smith S, et al. Sedentary behaviour is associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in people with psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vancampfort D, Probst M, Knapen J, Carraro A, De Hert M. Associations between sedentary behaviour and metabolic parameters in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Janney CA, Ganguli R, Richardson CR, et al. Sedentary behavior and psychiatric symptoms in overweight and obese adults with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders (WAIST Study). Schizophr Res. 2013;145:63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gomes E, Bastos T, Probst M, Ribeiro JC, Silva G, Corredeira R. Effects of a group physical activity program on physical fitness and quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia. Ment Health Phys Act. 2014;7:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lindamer LA, McKibbin C, Norman GJ, et al. Assessment of physical activity in middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;104:294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leutwyler H, Hubbard EM, Jeste DV, Miller B, Vinogradov S. Associations of schizophrenia symptoms and neurocognition with physical activity in older adults with schizophrenia. Biol Res Nurs. 2014;16:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Snethen GA, McCormick BP, Lysaker PH. Physical activity and psychiatric symptoms in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, Scheewe T, Remans S, De Hert M. A systematic review of correlates of physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schuhfried. Vienna Test System Psychological Assessment. Moedling, Austria: Schuhfried GmbH; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deijen JB, Orlebeke JF, Rijsdijk FV. Effect of depression on psychomotor skills, eye movements and recognition-memory. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee HJ, Kim L, Suh KY. Cognitive deterioration and changes of P300 during total sleep deprivation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klasik A, Krysta K, Krzystanek M, Skałacka K. Impact of olanzapine on cognitive functions in patients with schizophrenia during an observation period of six months. Psychiatr Danub. 2011;23(suppl 1):S83–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bezdicek O, Nikolai T, Hoskovcová M, et al. Grooved pegboard predicates more of cognitive than motor involvement in Parkinson’s disease. Assessment. 2014;21:723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Belsky DW, Caspi A, Israel S, Blumenthal JA, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive function in midlife: neuroprotection or neuroselection? Ann Neurol. 2015;77:607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang YC, Magasi SR, Bohannon RW, et al. Assessing dexterity function: a comparison of two alternatives for the NIH Toolbox. J Hand Ther. 2011;24:313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. García-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodríguez JI, Martín-Cantera C, et al. Physical exercise, fitness and dietary pattern and their relationship with circadian blood pressure pattern, augmentation index and endothelial dysfunction biological markers: EVIDENT study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hansen BH, Kolle E, Dyrstad SM, Holme I, Anderssen SA. Accelerometer-determined physical activity in adults and older people. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cain KL, Conway TL, Adams MA, Husak LE, Sallis JF. Comparison of older and newer generations of ActiGraph accelerometers with the normal filter and the low frequency extension. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soundy A, Roskell C, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D. Selection, use and psychometric properties of physical activity measures to assess individuals with severe mental illness: a narrative synthesis. Arch Psychiatric Nurs. 2014;28:135–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taiwan Executive Yuan Department of Health Bureau of Health Promotion. A Longitudinal Survey of Hypertension, Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia in Taiwan 2007. Tapei, Taiwan: Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Executive Yuan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Galling B, et al. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nguyen JC, Killcross AS, Jenkins TA. Obesity and cognitive decline: role of inflammation and vascular changes. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van der Berg JD, Stehouwer CD, Bosma H, et al. Associations of total amount and patterns of sedentary behaviour with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: the Maastricht Study. Diabetologia. 2016;59:709–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo X, Zhang Z, Wei Q, Lv H, Wu R, Zhao J. The relationship between obesity and neurocognitive function in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rashid NA, Lim J, Lam M, Chong SA, Keefe RS, Lee J. Unraveling the relationship between obesity, schizophrenia and cognition. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cox EP, O’Dwyer N, Cook R, et al. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive function in apparently healthy young to middle-aged adults: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19:616–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Ward PB, Teasdale S, Rosenbaum S. Integrating physical activity as medicine in the care of people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:681–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kimhy D, Lauriola V, Bartels MN, et al. Aerobic exercise for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia—the impact of frequency, duration, and fidelity with target training intensity. Schizophr Res. 2016;172:213–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vancampfort D, Probst M, De Hert M, et al. Neurobiological effects of physical exercise in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1749–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1343–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, et al. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr Res. 2016. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Firth J, Carney R, Elliott R, et al. Exercise as an intervention for first-episode psychosis: a feasibility study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]