Abstract

Financial exploitation (FE) of older adults is a social issue that is beginning to receive the attention that it deserves in the media thanks to some high profile cases, but empirical research and clinical guidelines on the topic are just emerging. Our review describes the significance of the problem, proposes a theoretical model for conceptualizing FE, and summarizes related areas of research that may be useful to consider in the understanding of FE. We discuss structural issues that have limited interventions in the past and make specific public policy recommendations in light of the largest intergenerational transfer of wealth in history. Finally, we discuss implications for clinical practice.

Overview

Financial exploitation of older adults is a highly significant social problem that to date, has not received much attention from the field of psychology. Data sources tracking financial exploitation report that financial exploitation has been increasing with losses of approximately $ 2.9 billion dollars / year. Psychological risk factors are well established and psychological outcomes have recently been demonstrated. Financial exploitation can occur at any stage of the lifespan and the literature regarding prevalence amongst older adults has been mixed in terms of supporting a theory that older adults are more “susceptible” to fraud. However, there has been literature that documents that older adults are targeted disproportionately, and are less likely to report financial exploitation (Acierno et al. (2010) National elder abuse survey). We believe that while any individual can be a victim of financial exploitation, older adults present with particular vulnerabilities that are often exploited for financial gain. Financial capacity is an important component for our conceptual model of financial exploitation. While it is certainly the case that older adults who retain capacity may become victims of exploitation, even subtle cognitive changes can increase risk of financial exploitation. In this section we provide a definition and description of financial exploitation and provide a conceptual model from the fields of financial decision-making and capacity. Recommendations for practice and policy include three major issues; (1) Improving collaboration across a variety of professions, (2) Improving the empirical base for new assessment tools and (3) Increasing the amount of federal funding being directed towards the problem of older adult financial exploitation.

What is Financial Exploitation (FE)

Financial exploitation has been defined by the National Center on Elder Abuse (NCEA, http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/FAQ/Type_Abuse/index.aspx, accessed September 24, 2015) as the illegal or improper use of an elder’s funds, property, or assets. FE can take many guises and examples include, but are not limited to, thefts and scams, unauthorized access to accounts (cashing an elderly person’s checks without authorization or use of ATM card without permission); forging an older person’s signature; misusing or stealing an older person’s money or possessions; coercing or deceiving an older person into signing any document (e.g., contracts or will); and the improper use of conservatorship, guardianship, or power of attorney. In this review, we use the term financial exploitation broadly to encompass all of the types of financial losses to an elder. We use the term fraud only in cases to imply criminal deception intended to result in financial gain.

Significance of the Issue

The U.S. has no national reporting mechanism to track the financial exploitation of elders, but based on available research the prevalence has been estimated to be 3.5 % to 20 % of adults over 65 years of age depending upon the demographics and methodology employed (R. Acierno, Hernandez-Tejada, Muzzy, & Steve, 2009; Beach, Schulz, Castle, & Rosen, 2010; DeLiema, Gassoumis, Homeier, & Wilber, 2012; Lachs & Berman, 2011). There is some evidence that FE and the associated financial losses has been increasing (MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2011). MetLife (2011) reported that the annual financial loss of elder financial abuse is estimated to be at least $2.9 billion dollars, a 12 % increase from the $2.6 billion dollars estimated in 2008. In the Metlife review 51 % of fraud was perpetrated by strangers, 34 % was perpetrated by family, friends, and neighbors, 12 % was perpetrated within the business sector, and Medicare and Medicaid Fraud comprised the last 4%.

The Elder Investment Fraud and Financial Exploitation Survey (The Investor Protection Trust, 2010) surveyed 2,022 individuals in the United States including 590 adults age 65 and older and 706 adult children with at least one parent aged 65 or older. Some key findings from this study included that 20 % of older adults reported being taken advantage of financially in terms of an inappropriate investment, unreasonably high fees for financial services, or outright fraud.

Financial exploitation may be even higher in minority communities (Dong, 2015). A recent study of Latino Americans in Los Angeles indicated that 40 % acknowledged experiencing all types of elder mistreatment but only 2 % reported it (DeLiema et al., 2012). In African-American populations, Beach et. al. reported that African-Americans were three times as likely to report financial exploitation than white respondents. Lichtenberg and colleagues sampling of a largely African-American population found self-reported financial exploitation to be 18% when using an 18-month look back period (Lichtenberg et al., 2015a). Using the Psychosocial Leave Behind Questionnaire (Smith et al., 2013); a sub-study of the large population based Health and Retirement study Lichtenberg et al. (2016) examined the prevalence of fraud in older adults. Among older adults, the overall reported prevalence of fraud across a 5-year look back increased significantly between 2008 and 2012: from 5.0% (347 out of 6,920) to 6.1% (442 out of 7,253), for a 22% increase. Predictors of fraud included both psychological vulnerability and demographic variables. Of particular relevance to this paper, older adults who experienced having low social needs fulfillment and depression were significantly more likely to experience fraud.

Beyond financial losses, older adults suffer declines in mental health and in physical health. Older adults who have been victimized have been reported to demonstrate lower levels of confidence and increased rates of depression, placing them at greatly increased risk for future victimization. Lichtenberg and colleagues (2015a) reported in study of 69 older African Americans that 18% had experienced financial exploitation within the past year, and that psychological vulnerability and undue influence risk factors significantly differentiated those who had been exploited from those who had not. In addition, those who were exploited were less confident of making significant financial decisions and less satisfied with their finances overall.

In summary, financial exploitation is a highly significant social problem. Financial exploitation results in financial losses which is estimated conservatively at $ 2.9 billion / year. Victims of financial exploitation also report increases in mental health symptoms and decreases in confidence following such a loss. Clinicians working with older adults may see an increase in mental health symptoms or risk factors (loss) prior to victimization, and see an increase of symptoms following an incident of financial exploitation.

The Nature of Financial Exploitation

Financial exploitation is a broad term that can encompass many different behaviors. As a result, risk factors can vary depending on the method of exploitation. In some cases, the victim is simply unaware of the exploitation and the loss of funds. This type of exploitation can happen through fraudulent credit card transactions, double billing, identity theft, and other false charging approaches (slamming, phone charges). Individuals who use technology, credit cards, cell phones, and have relatively more exposure (more transactions) are at increased risk (Federal Trade Commission, https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/scam-alerts, accessed September 27, 2015). These types of cases rely on a victim’s inattention and can impact high functioning as well as lower functioning seniors.

In other cases, the victim is deceived and believes that they are engaged in a legitimate transaction when they are not. The victims are aware of the transaction, and have consented, but were deceived regarding its true nature. These cases include mass marketing fraud such as sweepstakes scams, false investment scams, and others designed to deceive the victim. Victims in these types of scams rarely know the perpetrator who may provide a false name to develop a relationship, but it is typically anonymous. For example, in the “grandparent scam” (https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2012/april/grandparent_040212, downloaded September 25, 2015), an older man received a phone call that his grandson, Josh, was in a jail in Mexico and would need $5,000 bail before release. The victim believed the caller because he had a grandson, Josh, who was in Mexico for spring break and quickly agreed to the terms. The victim in this case was not cognitively impaired, but did not think to check on Josh through a phone call or other family members. Instead, the scammers evoked a strong social need of the grandparent and used common techniques of persuasion such as urgency (Cialdini, 2007; DeLiema, Yon, & Wilber, 2014). The scammers also use Facebook and other social media to develop a plausible story accessing information that would have been simply unavailable even 15 years ago. Scams relying on internet information and contacts are becoming increasingly prevalent. Perpetrators can reside outside the U.S. where they face little risk of prosecution and extradition.

Another type of financial exploitation involves deception by trusted others such as family members, caregivers and advisors. In these cases, the older adult may or may not be aware that the transactions have occurred. These cases may involve implied consent and coercion where a trusted other gains access to financial information and assets and then uses them for personal gain. In summary, financial exploitation may occur in different psychological contexts (no awareness, consent, implied consent) and may co-occur with other types of financial exploitation.

III. Framework and Description of Relevant Theory and Research related to Financial Exploitation

Conceptual Model

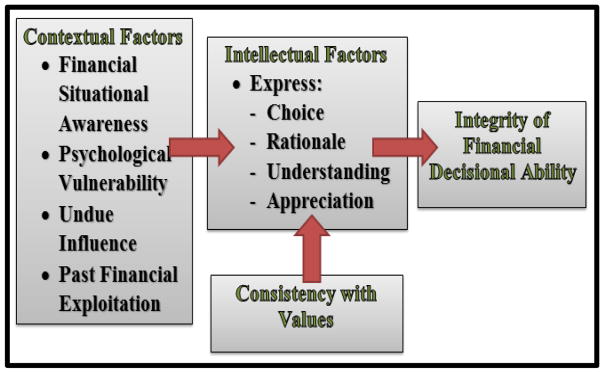

Financial elder exploitation at the individual level is a complex problem that can include cognitive, financial, emotional, and contextual factors. In terms of a theoretical framework, we begin with drawing on work from financial decision-making and aging. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual foundation, which combines the key contextual and intellectual / cognitive factors that influence decision-making. Contextual factors include the context of the financial decision and individual difference variables such as susceptibility to undue influence, or excessive persuasion. These contextual factors directly influence the intellectual factors associated with decisional abilities for a sentinel financial transaction or decision. Lichtenberg developed the conceptual model as a basis for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS). Preliminary evidence is available for both the scale’s reliability and validity (see Lichtenberg et al., 2015a, In press). In essence, we propose that cognitive abilities underlie sound financial management and declines in these abilities compromise good financial decision making, These declines result in susceptibility to financial exploitation.

Figure 1.

Key Components of the Financial Decisional Abilities Model

Financial Capacity and Decision-Making: Legal Standards

Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) examined the legal standards used by states to determine financial incapacity and identified the decision-making abilities or intellectual factors involved in making informed decisions: choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning. These kernel intellectual factors have been reiterated as fundamental aspects of decisional abilities (ABA/APA, 2008) and are included in the Lichtenberg conceptual model of financial decision-making. Specifically, the older adult must be capable of clearly communicating his or her choice. Understanding is the ability to comprehend the nature of the proposed decision and provide some explanation or demonstrate awareness of its risks and benefits. Appreciation refers to the situation and its consequences, and often involves their impact on both the older adult and others; Reasoning includes the ability to compare options—for instance, different financial options in the case of financial decision making—as well as the ability to provide a rationale for the decision or explain the communicated choice. Therefore, in our model, intellectual factors refer to the functional abilities required for financial decision-making capacity and include an older adult’s ability to (a) express a Choice, (b) communicate the Rationale for the choice, (c) demonstrate Understanding of the choice, and (d) demonstrate Appreciation of the relevant factors involved

The intellectual factors, unless they are overwhelmed by the impact of the contextual factors, are the most proximal and central to determining the integrity of financial decisional abilities.

Specific intellectual / Cognitive Factors related to Financial Capacity and Financial Exploitation: Math, Financial Execution Skills and Aging

Numeracy (Schwartz, Woloshin, Black, & Welch, 1997) and the use of numerical reasoning during decision-making is often lower among older adults resulting in older adults’ lower comprehension and worse decision making when unfamiliar numerical information is present (e.g., Hibbard, Peters, Slovic, Finucane, & Tusler, 2001). In some older adults low numeracy reflects a decline from earlier numeric skills, in others low numeracy may reflect lower lifelong abilities (S. A. Wood, Liu, Hanoch, & Estevez-Cores, 2015).

Numeracy is a distinct construct from basic calculation abilities and influences not only an individuals’ ability to “do the math”: but also their engagement, comprehension, and use of numeric information in decision-making (Reyna, Nelson, Han, & Dieckmann, 2009). Numeracy appears to be related to deliberative reasoning in the sense that information derived from numbers is more easily extracted and comprehended in high numerate individuals. As a result, the low numerate appear to be influenced by competing irrelevant affective factors (Peters et al., 2006). Because older adults tend to be less numerate than their younger counterparts and therefore may be at higher risk for poor financial decision-making (Jenkins, Ackerman, Frumkin, Salter, & Vorhaus, 2011).

Work by Lusardi and colleagues (e.g., Lusardi & Mitchell, 2007, 2011) has highlighted the important link between numeracy and the ability to understand, grapple, and utilize financial information. Their studies show that numeracy is related to the ability to correctly answer financial questions, make better financial decisions about their retirement saving, and more likely to pay off loans and credit cards (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011; Lusardi & Tufano, 2009). Also, it has been argued that one way of protecting older adults from FE is to increase their financial knowledge (Gamble, Boyle, Yu, & Bennett, 2014).

In a recent study examining cognitive risk factors for financial exploitation among older adults, high numeracy was found to be a significant predictor of decreased risk after controlling for other demographic variables (S. A. Wood et al., 2015). Less numerate participants’ self-reported risk was significantly higher as assessed by the Older Adult Financial Exploitation Measure (Conrad, Iris, Riley, Mensah, & Mazza, 2012). Importantly, numeracy remained a significant predictor in the presence of other risk factors, including dependency, physical and mental health, as well as overall cognition. Among healthy adults, researchers have shown that higher cognitive abilities are associated with increased likelihood to plan for the future and participate as investors in financial market (Cole & Shastry, 2009).

How does cognitive impairment impact financial decision-making?

Plassman et al. (2008) used a subsample of the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study to estimate the prevalence of cognitive impairment, both with and without dementia, in the U.S.. The baseline data included more than 1,700 older adults and the longitudinal study 856 individuals age 71 and older. The baseline data indicated that in 2008 an estimated 5.4 million people age 71 and older had cognitive impairment without dementia and an additional 3.4 million had dementia. The findings are striking, in that they show a much higher rate of cognitive impairment than found in any other sample. The dramatically increasing numbers of older adults in America underscores the fact that the number of people with cognitive impairment will close to triple in the next 35 years (Hebert, Scherr, Bienias, Bennett, & Evans, 2003).

The impact of age-related dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) on financial capacity (Marson, 2001) threatens financial autonomy. For many years Dr. Daniel Marson and his colleagues have examined how major neurocognitive disorders impact financial capacity, defined by them as the ability to manage money and financial assets in ways consistent with one’s values or self-interest. Pinsker, Pachana, Wilson, Tilse, and Byrne (2010) proposed that three general abilities underlie financial capacity: (1) declarative knowledge (e.g., the ability to describe financial concepts); (2) procedural knowledge (e.g., the ability to write checks); and (3) sufficient judgment to make sound financial decisions. Stiegal (2012) vividly described the fact that financial capacity and financial exploitation are connected. That is, that older adults’ vulnerability is twofold; (1) the potential loss of financial skills and financial judgment; and (2) the inability to detect and therefore prevent financial exploitation.

It is now understood that dementia syndromes may have an onset that lasts decades with relatively “mild” symptoms emerging years prior to a full blown dementia syndrome (Sperling et al., 2011). In other cases, the “mild” symptoms do not progress but persist resulting in subtle declines. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) refers to the stage of the illness where cognitive deficits are present but day-to- day functioning is relatively intact. The pattern of deficits varies by etiology, but many individuals manifest deficits in memory, executive functioning and calculation during this stage of the disease. In a recent paper Duke Han and colleagues (2015), reported that in a sample of non-demented elderly individuals, decreased gray matter volume in frontal and temporal regions was significantly related to susceptibility to telemarketing scams. In many ways, these pre-dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) individuals are the perfect victim. They retain control of their assets and are out in the community increasing their exposure.

In a study of substantiated fraud victims, Wood and colleagues found that the victim sample was more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia and evidenced poorer memory, calculation abilities, and executive functioning (Wood et al., 2014). These findings are consistent with a recent report examining undue influence cases in California (Quinn, Goldman, Nerenberg, & Piazza, 2010). Lichtenberg and colleagues (2015a) also found significant correlates between decision making abilities and neurocognitive variables such as the Mini Mental State Exam.

While the research on financial capacity and financial exploitation of older adults is still emerging, a parallel line of research has focused on the relationship between cognitive ability and financial execution skills. Based on a series of studies in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and moderate dementia, neuropsychological measures have been linked to financial incapacity including arithmetic abilities, executive functioning, and verbal memory (Griffith et al., 2003; Marson, Earnst, Jamil, Bartolucci, & Harrell, 2000; Martin et al., 2008). Decline in arithmetic skills was associated with impairment in financial capacity in the very earliest stages of mild cognitive impairment (Griffith et al., 2003). As the dementia progresses, declines in memory, language, judgment and executive functioning further erode an older adults financial decision making (Marson et al., 2000). Cognitive impairment and cognitive decline, therefore, serve as a significant risk factor for financial exploitation.

Contextual Factors related to Financial Exploitation: Susceptibility to Undue Influence

Undue influence refers to a dynamic between two individual that involves unfair or excessive persuasion by a stronger party over a weaker party. In work with older adults, typically a second party coerces the elder to act in a manner that is not in their best interest, taking advantage of their particular vulnerabilities that can include illness, dependency, mental illness, isolation, disability, and cognitive decline. Undue influence is a legal construct that is defined differently by the courts dependent upon jurisdiction (Peisah et al., 2009). Although legal definitions vary with regards to undue influence, typically definitions require some combination of the following aspects, (1) that there is a confidential or intimate relationship, (2) factors that increase the susceptibility of the elder are present, (3) that there is a power differential that results in susceptibility to coercion, and that (4) the coercion results in financial or testamentary decisions are suspicious (i.e., not proportionate to services provided; unnatural heir) (Peisah et al., 2009; Spar & Garb, 1992; S. A. Wood & Liu, 2012). Theoretical frameworks for understanding and explaining undue influence have included work from social psychology (N. J. Goldstein, Martin, & Cialdini, 2007), work with cult members (Singer, 1993) and those drawing from work on domestic violence (Steigel, from ABA and APA, 2008). Quinn et al. (2010) conducted a chart review of 25 cases in San Francisco Superior Court selected because probate court investigators or researchers had determined that there were elements of undue influence in the case. Impairments in executive functioning, judgment, and insight are commonly noted in this report.

In terms of financial exploitation undue influence is usually evoked in cases of testamentary capacity. However, the dynamic can also be used to understand financial exploitation more broadly. Work applying the concepts of undue influence and persuasion to financial exploitation of older adults is just emerging but is a promising future direction for the field (DeLiema et al., 2014).

In summary, we draw from a conceptual model of financial decision-making as a framework for thinking about the contextual and cognitive aspects of financial exploitation. We included in this model research related to legal standards, numeracy and financial literacy, neuropsychological studies of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, and undue influence. Overall, work from financial literacy and neuropsychological studies has highlighted the importance of working memory, episodic memory, executive functioning and calculation skills as critical for sound financial decision-making. Mild cognitive impairment can produce deficits that decrease financial skills, judgment, or both resulting in increased risk for financial exploitation. Undue influence refers to a relational dynamic that capitalizes on these vulnerabilities to resulting financial losses for the victim.

Applications from Social Psychology

Fraud is a highly lucrative business that has become increasingly organized and sophisticated. Social psychological work in the area of persuasion could be applied to the field of financial exploitation of the elderly to learn more about common tactics being used and to develop campaigns aimed at educating the public regarding the high prevalence of financial exploitation across the lifespan. Such a campaign could address ageist ideas to increase reporting in all age groups. It may also provide information regarding common safeguards to protect assets that are less intrusive than formal measures. For example, many banks have services that allow alerts if a certain amount of money is spent, or unusual transactions are conducted. Others allow for a third party (accountant) to view but not transfer funds providing a level of oversight. Although such an approach may not stop financial exploitation from occurring it has the potential to shift some individuals from “reacting” after victimization to a more proactive stance “protecting” their funds. Federal funding would be needed to study, develop, and empirically test such a campaign.

Social psychologists can also bring expertise from the field of stereotyping and discrimination. Older adults are frequently viewed stereotypically as (1) alike; (2) alone and lonely, (3) sick, frail and dependent, (4) depressed, (5) rigid and (6) unable to cope (Hinrichsen, 2006). This pervasive view portrays all older adults in a negative light, ignores the incredible heterogeneity of aging and the strengths and positive attributes of older adults. Thus, Ageism, pervasive discrimination against older adults, is widespread in the United States. Ageism is potentially one reason for the lack of general interest among psychologists in the issue of elder mistreatment in general and elder financial exploitation specifically. Stereotypes of lonely, frail helpless seniors may make it difficult to imagine interventions to stop exploitation.

Work on stereotype threat and aging to date has primarily focused on solicitations of stereotypes of poor memory (Hess, Aumen, 2003, B. Levy, 1996). Similar mechanisms may be interesting to explore regarding fears of looking foolish in financial exploitation cases. Ageist stereotype threats may well be related to the low reporting of financial elder abuse to authorities.

With regard to psychological health of older adults, ageism can translate into psychologist’s feelings of hopelessness in working with older adults, the expectation of poor progress, and finally translate into a lack of quality care provided by psychologists and their colleagues. Ageism underlies findings such as the under-utilization of screening for functional ability, cognitive and affective functioning and the over-estimation of late life depression by many health providers who work with older adults (Lichtenberg, 1998). In terms of financial decision-making, such under utilization may have disastrous consequences.

Limitations

There are several important limitations regarding our current knowledge of financial exploitation and its impact and here we focus on three: First, the health and mental health impact. While measures such as self-reported depression, and psychological vulnerability were significant predictors of financial exploitation in cross-sectional and longitudinal research, there is scant data on how the experience of financial exploitation impacts future health and mental health. In addition to the need for more longitudinal data after exploitation, there are a few other issues that make this difficult. First, comorbid risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia, and depression already impact financial abilities and make older adults more susceptible to FE. Second, there is no gradient of the severity of FE measure, and one might expect that mental health issues may be impacted only after a threshold of FE is met. Finally, underreporting of FE limits our ability to fully understand the health and mental health impacts of FE.

A second limitation of FE knowledge are how to advise families, and the general society on best practices or interventions to prevent FE. We know little about the dynamics of discussions about wealth between older adults and their adult children. As money management skills deteriorate in the older adult population several new businesses are appearing such as bill payment services, bank account alert services, and fraud protection services. It is not clear how well these services are received and what their impact is.

Finally, we know almost nothing about the trade-off between swinging the balance more in favor of autonomy even in the face of deficits in numeracy, cognitive decline and psychological vulnerability. What are the harms of reducing autonomy in individuals whose financial decision making is declining but not excessively so. The ethical balance of autonomy and beneficence/paternalism is always top of mind to the clinician but remains a dilemma in many clinical cases.

Social Issues and Policy Implications

In the end, however, structural issues in society continue to allow the predictable and common financial exploitation of older adults to occur. Despite the growing prevalence and adverse impact of elder financial abuse, cases of financial exploitation are difficult to prevent, detect, and to prosecute. Why? Although this problem is undoubtedly multifaceted, an important root cause is the distributed nature of case detection. That is, incidences of elder financial exploitation affect multiple professionals across multiple settings including law enforcement, adult protective service, financial services, physicians, psychologists and legal professionals. It is currently noted that case detection is the major impediment to the identification of elder financial abuse. Specifically, most professionals coming in contact with financial exploitation are not formally trained in the assessment of key variables underlying financial judgment and may simply not detect the exploitation. Once detected, these individuals are often unsure of how to proceed in an area that crosses legal jurisdictions (civil, criminal, probate at both State and Federal Levels).

Another challenge facing detection of financial exploitation is the reluctance of older adults to report once they have become aware of it (Acierno et al., 2010; Acierno, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Stark-Riemer, 2003). Because older adults often do not self-report abuse, the vast majority of states have enacted mandatory reporting statutes. These laws require certain groups to relay reasonable suspicions of elder abuse to authorities. Mandatory reporting is based on the belief that individuals who come in contact with at-risk older adults who are unable or unwilling to self-report are in the best position to observe and report suspected cases of abuse. (The United States Department of Justice, http://www.justice.gov/elderjustice/research/how-financial-exploitation-is-defined-and-detected.html, accessed 9/29/15). A second, very real fear is the concern that their financial decision making abilities will be challenged once the exploitation has been made known. A third concern is an unwillingness to accuse and potentially prosecute family members and trusted others of exploitation.

Recommendations for practice and policy include three major issues; (1) Improving the use of collaboration across a variety of professions, (2) Improving the empirical base for new assessment tools and (3) Increasing the amount of federal funding being directed towards the problem of older adult financial exploitation. Assessment tools must be created, empirically tested, and widely used by both criminal justice and non-criminal justice professionals. Elder financial exploitation affects multiple professionals across multiple settings, including law enforcement; adult-protective, financial, health, and social services; and the legal system. In response to this problem, in 2003, the Department of Justice initiated a federal program designed to strengthen collaborative responses to family violence. This led to the creation of 80 Family Justice Centers—multidisciplinary alliances that coordinate intervention resources, strengthen community access, and provide education about family violence and elder abuse. A second trend has been the creation of Elder Abuse Forensic Centers, an interdisciplinary team model designed to increase prosecutions of elder mistreatment that includes social services, law enforcement, psychologists, physicians, and financial services professionals.

Most criminal justice professionals who come in contact with financial exploitation have not been formally trained in the assessment of the key variables that underlie financial judgment. In addition, standardized tools that are available to non-psychologist professionals to guide such assessments do not exist. During a recent webinar by the leaders of an Elder Abuse Forensic Center, sponsored by the National Adult Protective Services Association, the lack of easily administered tools to assess financial judgment (capacity) was identified as the chief weakness in the current identification and investigation process (Gassoumis, Navarro, & Wilber, 2015). Clearly, adult protective services professionals, law-enforcement professionals, and prosecutors would benefit by having assessment tools available to screen for decision making in older adults.

Ideally, financial service industry front-line professionals should be held to a higher standard to ensure that their clients can comprehend and appreciate the information provided. This may entail training or requiring professionals to bear the burden of documenting capacity when confronted with significant financial transactions being made by older adults. Such responsibility would motivate professional organizations to provide training in the assessment of financial decision-making tools. At present, a reverse incentive is in place to move ahead with transactions as financial advisors typically make commissions based on the sale of products. At the very least, a red flag should be triggered when an older adult makes a suspicious large purchase, bank transfer, investment or withdrawal. Professionals and staff in certain contexts must have higher standards of practice that may include training, and knowledge of decision-making abilities. The list of potential professionals is broad and includes bankers, financial planners, alternative financial services providers, CPAs, insurance sales personnel, trust officers, geriatric care managers, social and health-service workers, and even employees at places such as Walmart where prepaid card scams have proliferated (Goldstein, 2014).

Finally, Pillemer, Connolly, Breckman, Spreng, & Lachs (2015) highlight the importance of more research funding and emphasize that Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia render older adults more susceptible to all types of elder abuse. NIH—and, in particular, the National Institute on Aging—should increase its funding for research on the detection of financial exploitation and effective interventions. NIH’s translational initiatives should require researchers to partner with front-line professionals who regularly deal with older adults making significant financial decisions and transactions, as well as with those in the criminal-justice system. Second, the Department of Justice—which, through the National Institute of Justice, has recently focused on the financial exploitation of older adults—should be allocated increased resources to fund more work in this area. And third, the Alzheimer’s Association’s investigator-initiated grants should have funds set aside in its annual international research competition for the study of elder abuse and financial exploitation among individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. It is particularly important for the Alzheimer’s Association to show leadership in this area since they have such a strong advocacy role throughout the United States. With sufficient support integrated approaches to prevent and prosecute financial exploitation can be improved and the trauma of financial victimization can be avoided.

Clinical Implications

Focusing on elder financial capacity, even cognitive impairment without dementia often renders older adults more vulnerable to financial exploitation. Psychologists have expertise in assessing whether an older adult is vulnerable, which is a key requirement for the prosecution of perpetrators of financial exploitation. Declining cognitive abilities and mental-health concerns are often evidence that an older adult is vulnerable. In addition to determining vulnerability, however, it is crucial that psychologists develop new assessment measures that have been tested empirically that incorporate contextual and cognitive aspects of financial decision-making.

To address financial exploitation, assessment in new conceptual and measurement approaches is needed that can be used by professionals in multiple settings. In the whole person dementia assessment approach (Mast & Gerstenecker, 2010), tools are used to directly measure the older adult’s current decisions, and in the “decisional abilities” tradition such as found in the MacArthur Assessment of Treatment Decisions (Appelbaum & Grisso, 1988) judgment is the key element of assessing capacity in any domain. Creating and validating tools that can be used by non-psychologists will also help in raising the standard of practice among non-mental health professionals. Financial decision making incapacity and financial exploitation are two sides of the same coin; impaired decision making skills (capacity) is also accompanied by increased vulnerability and decreased ability for self-protection (exploitation). Financial services and legal professionals must be expected to consider and assess both of these when working with an older adult making a sentinel financial decision. Having valid and efficient tools can make a tremendous difference in case detection of vulnerability and incapacity.

VI. Conclusions

Financial exploitation of older adults is a significant social problem that is increasing in prevalence. However, to date, there has not been much research from psychologists on the subject. In this review we describe relevant areas of psychological research to the problem and also provide some solutions. In general, we propose a model that integrates contextual and cognitive factors based on work that has been done previously on financial decision-making. In terms of policy recommendations we suggest an increase in research funding, development of better tools for the assessment of financial decision-making, broader awareness of the issue among related professionals and the general public.

Contributor Information

Stacey Wood, Professor of Psychology, Scripps College, 1030 Columbia Ave. PO 4082, Claremont, CA 91711, 909-607-9505

Peter A. Lichtenberg, Director and Professor, Institute of Gerontology, Wayne State University, 87 E. Ferry Street, Detroit, MI 48202, 313-664-2633.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(2):292–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, Steve K. National elder mistreatment study. 2009 (No. 226456). Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/226456.pdf.

- Acierno R, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Stark-Riemer W. Assessing elder victimization--demonstration of a methodology. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38(11):644–653. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0686-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0686-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging and American Psychological Association. Assessment of older adults with diminished capacity: A handbook for psychologists. Washington, DC: American Bar Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;319(25):1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Castle NG, Rosen J. Financial exploitation and psychological mistreatment among older adults: Differences between African Americans and non-African Americans in a population-based survey. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):744–757. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq053. http://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB. Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York, NY: Harper Business; 2007. (Revised Edition) [Google Scholar]

- Cole SA, Shastry GK. Smart money: The effect of education, cognitive ability, and financial literacy on financial market participation. Working Papers 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Riley BB, Mensah E, Mazza J. Developing end-user criteria and a prototype for an elder abuse assessment system 2012 [Google Scholar]

- DeLiema M, Gassoumis ZD, Homeier DC, Wilber KH. Determining prevalence and correlates of elder abuse using promotores: Low-income Immigrant Latinos report high rates of abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(7):1333–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04025.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLiema M, Yon Y, Wilber KH. Tricks of the trade: Motivating sales agents to con older adults. The Gerontologist. 2014 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu039. http://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dong XQ. Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63(6):1214–1238. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13454. http://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke Han S, Boyle PA, Yu L, Arfanakis K, James BD, Fleischman DA, Bennett DA. Grey matter correlates of susceptibility to scams in community-dwelling older adults. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9422-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-015-9422-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Federal Trade Commission. Scam alerts. n.d Retrieved from https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/scam-alerts.

- Gamble KJ, Boyle P, Yu L, Bennett DA. Aging and financial decision making. Management Science. n.d doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassoumis ZD, Navarro AE, Wilber KH. Protecting victims of elder financial exploitation: the role of an Elder Abuse Forensic Center in referring victims for conservatorship. Aging & Mental Health. 2015;19(9):790–798. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.962011. http://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.962011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M. Senate panel to look into MoneyPak prepaid scams. New York Times. 2014 Nov 18; Retrieved from http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/11/18/senate-panel-to-look-into-moneypak-prepaid-scams/?_r=1.

- Goldstein NJ, Martin SJ, Cialdini RB. Yes!: what science tells us about how to be persuasive. London: Profile; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith HR, Belue K, Sicola A, Krzywanski S, Zamrini E, Harrell L, Marson DC. Impaired financial abilities in mild cognitive impairment: A direct assessment approach. Neurology. 2003;60(3):449–457. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.3.449. http://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.60.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60(8):1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. http://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Peters E, Slovic P, Finucane ML, Tusler M. Making health care quality reports easier to use. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 2001;27(11):591–604. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen GA. Why multicultural issues matter for practitioners working with older adults. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2006;37(1):29–35. http://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.37.1.29. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins A, Ackerman R, Frumkin L, Salter E, Vorhaus J. Literacy, Numeracy and Disadvantage among Older Adults in England. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs MS, Berman J. Under the radar: New York State elder abuse prevalence study. New York, NY: William B. Hoyt Memorial New York State Children, Family Trust Fund, New York State Office of Children and Family Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Ficker LJ, Rahman-Filipiak A. Financial decision-making abilities and exploitation in older African Americans: Preliminary validity evidence for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS) Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2015 doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1078760. 150818092716004. http://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2015.1078760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lichtenberg PA, Sugarman M, Paulson D, Ficker LJ, Rahman-Filipiak A. Psychological and functional vulnerability predicts fraud cases in older adults: results of a nationally representative longitudinal study. Clinical Gerontologist. 2016 doi: 10.1080/07317115.2015.1101632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implication for financial education. Business Economics. 2007;42(1):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacry around the world: An overview. NBER Working Paper 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Tufano P. Debt literacy, financial experience and overindebtedness. Working Papers 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC. Loss of financial competency in dementia: Conceptual and empirical approaches. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition (Neuropsychology, Development and Cognition: Section B) 2001;8(3):164–181. http://doi.org/10.1076/anec.8.3.164.827. [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC, Earnst KS, Jamil F, Bartolucci A, Harrell LE. Consistency of physicians’ legal standard and personal judgments of competency in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(8):911–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Griffith HR, Belue K, Harrell L, Zamrini E, Anderson B, … Marson D. Declining Financial Capacity in Patients With Mild Alzheimer Disease: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):209–219. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318157cb00. http://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e318157cb00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast BT, Gerstenecker A. Handbook of Assessment in Clinical Gerontology. Elsevier; 2010. Screening instruments and brief batteries for dementia; pp. 503–530. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780123749611100193. [Google Scholar]

- MetLife Mature Market Institute. The MetLife study of elder financial abuse: Cimes of occasion, desperation, and predation against America’s elders. New York, NY: 2011. Retrieved from https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2011/mmi-elder-financial-abuse.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse. Types of Abuse. n.d Retrieved from http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/FAQ/Type_Abuse/index.aspx.

- Peisah C, Finkel S, Shulman K, Melding P, Luxenberg J, Heinik J, … Bennett H. The wills of older people: risk factors for undue influence. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(01):7. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008120. http://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208008120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Connolly MT, Breckman R, Spreng N, Lachs MS. Elder mistreatment: Priorities for consideration by the White House Conference on Aging. The Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):320–327. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu180. http://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker DM, Pachana NA, Wilson J, Tilse C, Byrne GJ. Financial capacity in older adults: A review of clinical assessment approaches and considerations. Clinical Gerontologist. 2010;33(4):332–346. http://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2010.502107. [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal M, … Wallace RB. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(6):427. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. http://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn MJ, Goldman E, Nerenberg L, Piazza D. Undue Influence: Definitions and Applications. Borchard Foundation Center on Law and Aging; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):943–973. doi: 10.1037/a0017327. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Black WC, Welch HG. The role of numeracy in understanding the benefit of screening mammography. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127(11):966–972. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00003. http://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MS. Undue influence and written documents: Psychological aspect. Cultic Studies Journal. 1993;10:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Fisher G, Ryan L, Clarke P, House J, Weir D. Psychosocial and lifestyle questionnaire 2006 – 2010. The HRS Psychosocial Working Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spar JE, Garb AS. Assessing competency to make a will. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(2):169–174. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, … Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiegel LA. An overview of elder financial exploitation. Generations. 2012;36:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- The Investor Protection Trust. Elder investment fraud and financial exploitation: A survey conducted for Investor Protection Trust. Washington, DC: 2010. Retrieved from www.investorprotection.org/downloads/pdf/learn/research/EIFFE_Press_Release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- The United States Department of Justice. Definition of financial exploitation. n.d Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/elderjustice/research/how-financial-exploitation-is-defined-and-detected.html.

- Wood SA, Liu PJ. Undue influence and financial capacity: A clinical perspective. Generations. 2012;36:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wood SA, Liu P-J, Hanoch Y, Estevez-Cores S. Importance of numeracy as a risk factor for elder financial exploitation in a community sample. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv041. http://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wood S, Rakela B, Liu PJ, Navarro AE, Bernatz S, Wilber KH, … Homier D. Neuropsychological Profiles of Victims of Financial Elder Exploitation at the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Forensic Center. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2014;26(4):414–423. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2014.881270. http://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2014.881270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]