Abstract

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) is a transmembrane protein that signals from the ER and contributes to the generation of an active spliced form of the transcriptional regulator X-box–binding protein 1 (XBP1). XBP1 is required for the terminal differentiation of B lymphocytes into plasma cells, and IRE1 also participates in this differentiation event. A study in this issue of the JCI reveals, quite unexpectedly, that IRE1 is also required early in B lymphocyte development for the induction of the machinery that mediates Ig gene rearrangement.

Commitment of a common lymphoid progenitor to the B lineage requires the initiation of Ig gene rearrangement. After a B cell encounters and responds to antigen, it eventually differentiates into an antibody-secreting plasma cell. It has become apparent over the past few years that events in the ER provide important cues for the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells. A role for the ER as a source of signals that drive early events in B cell development is now beginning to emerge.

A little over a decade ago, an intriguing and novel intracellular signaling pathway was described in budding yeast (1, 2). Misfolded proteins in the ER were shown to activate an integral membrane ER resident protein kinase called inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and thus induce the synthesis of chaperone genes that assist in the retention of misfolded proteins in the ER and in the facilitation of their proper folding and assembly. IRE1 contains a lumenal stress-sensor domain, a hydrophobic transmembrane anchor sequence, and cytosolic kinase and endoribonuclease domains (Figure 1). Oligomerization of IRE1 induced by misfolded proteins in the ER lumen results in the activation of IRE1 kinase activity, and the consequent autophosphorylation-dependent activation of the adjacent endoribonuclease domain (3). This latter domain catalyzes an unusual splicing event that generates a shorter spliced form of an mRNA encoding a transcription factor called HAC1. This in turn orchestrates the transcriptional activation of a battery of target genes that include many ER chaperones and enzymes that facilitate protein folding. This prototypic stress-regulated signaling pathway is known as the unfolded protein response (UPR) or the ER stress pathway. A number of different causes of ER stress can result in enhanced protein misfolding. These include disordered calcium homeostasis, viral infection, heat shock, and nutrient deprivation, to name a few (4, 5). Apart from the physiological and developmental roles of the ER stress pathway, some of which are discussed below, there is growing evidence for its involvement in the pathogenesis of a number of clinical conditions (5–9).

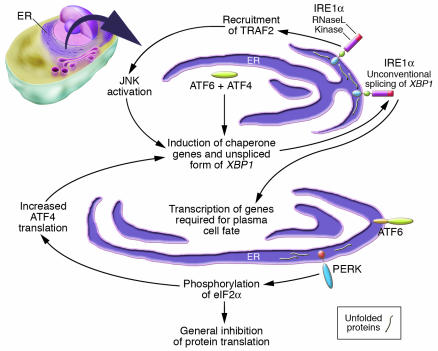

Figure 1.

Multiple sensors initiate the UPR in vertebrates. IRE1α and PERK are integral-membrane ER kinases whose lumenal domains are triggered by misfolded proteins in the ER. IRE1α and its yeast homolog, IRE1, contain a lumenal stress-sensing domain (blue) as well as cytosolic kinase (magenta) and endoribonuclease (RNaseL, red) domains. ATF6 is another stress sensor, which is cleaved in response to stress to yield a fragment (green) that is transported to the nucleus. Both ATF6 and Blimp-1 (not shown) may contribute to the transcriptional induction of XBP1. Very little is understood as to how IRE1α, a kinase that is activated by unfolded proteins in the ER, contributes to the induction of Rag1, Rag2, and TdT to initiate and sustain V(D)J recombination during early B cell development.

Sensors of the UPR in vertebrates

In vertebrates, ER stress is monitored by 3 major sensors (Figure 1). These include IRE1 and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase–like ER kinase (PERK), which are integral membrane proteins located in the ER, in addition to activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), which is a type II integral membrane ER protein that contains a C-terminal lumenal domain and can release a cytosolically-oriented N-terminal basic leucine zipper–containing transcription factor in situations of ER stress (4, 10). Murine IRE1α and β (the α isoform is ubiquitous while β is restricted to the gut) and PERK contain very similar lumenal stress-sensing domains. These lumenal domains are normally physically associated with the ER chaperone, Bip. However, misfolded proteins associate with Bip, causing it to be released from IRE1 and PERK. The release of Bip results in the oligomerization and activation of these kinases. The cytoplasmic regions of murine IRE1 proteins contain kinase and endoribonuclease domains much like their yeast counterparts, and IRE1 in vertebrates lies upstream of X-box–binding protein 1 (XBP1), the vertebrate homolog of HAC1. PERK kinase activity results in the phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) in the cytosol (11). This results in a general inhibition of protein translation, thereby indirectly inhibiting the accumulation of toxic misfolded proteins (Figure 1). However, phosphorylated eIF2α also mediates the specific and selective enhancement of the translation of ATF4. Transcription of a number of UPR-regulated genes, such as C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) and Bip, is enhanced by ATF4. Stress also facilitates the egress of unprocessed ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi, and this in turn results in the sequential cleavage in the Golgi of ATF6 by the site-1 and site-2 proteases, releasing active ATF6. ATF6 in collaboration with B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1; which represses the PAX5 inhibitor), enhances the transcription of XBP1, which is initially generated as a larger, incompletely spliced RNA. IRE1α is largely localized to the inner nuclear membrane (10). This protein becomes an active kinase during conditions of stress, and its endoribonuclease activity mediates a unique splicing event generating a distinct shorter, functional form of XBP1. In addition, activated IRE1 can recruit TNF receptor–associated factor 2 (TRAF2), which in turn may contribute to the activation of JNK. It is believed that JNK activation and induction of the CHOP transcription factor as well as the activation of caspases 7 and 12 may all contribute to the apoptotic death of severely stressed cells.

B lymphocyte development and ER stress signaling

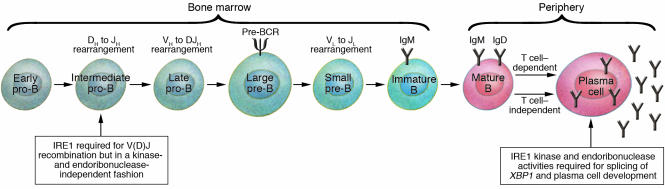

During B lymphocyte development, initially pro–B cells rearrange the Ig heavy chain locus in a step-wise fashion (Figure 2). The Rag1 and Rag2 proteins are lymphoid-specific proteins that mediate the site-specific recognition and cleavage of DNA during V(D)J recombination. In addition to Rag1 and Rag2, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) is another lymphoid-specific factor that contributes to the generation of diverse antibodies. Approximately 1 in 3 pro–B cells eventually makes an in-frame rearrangement at the Ig heavy chain locus that is capable of generating the μ heavy chain protein. A portion of the membrane form of the μ heavy chain assembles with surrogate light chains to generate a structure known as the pre–B cell receptor, which drives further B cell development. Following the rearrangement of both Ig heavy and light chain genes and the synthesis of fully assembled immunoglobulins, pre–B cells differentiate further into immature B cells and emerge in the periphery as naive B cells. The activation of naive B cells by either T cell–independent or T cell–dependent antigens results in their eventual differentiation into specialized antibody-secreting cells known as plasma cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A simplified overview of B cell development. Differentiation is initiated in the bone marrow in an antigen-independent manner and is completed in the periphery in response to antigenic challenge. Rearrangement of the Ig heavy chain is initiated in pro–B cells and involves sequential DH to JH and VH to DJH rearrangements. Once light chain rearrangement is completed, B cells emigrate to the periphery and give rise to multiple peripheral lineages (not shown). Peripheral B cells activated by either T cell–dependent or T cell–independent antigens differentiate into plasma cells. In this issue, Zhang et al. (15) demonstrate that IRE1 is required for V(D)J recombination early in B cell development, but in a kinase- and endoribonuclease-independent fashion. IRE1 kinase and endoribonuclease activities are required for the splicing of XBP1 and plasma cell development. Pre-BCR, pre–B cell receptor.

Apart from its role in cellular adaptation, the ER stress response also participates in developmental decisions in vertebrates as well as invertebrates (12, 13). XBP1 is critical for the development of plasma cells, and it contributes to the expression not only of ER proteins but also of many genes that contribute to the phenotypic changes that characterize secretory cells, such as expansion of the ER and induction of chaperones, and enzymes such as protein disulfide isomerases (14). In this issue of the JCI, Zhang et al. (15) use a gene inactivation approach to show that IRE1α is required for the development of plasma cells. Since IRE1α lies upstream of XBP1, this clarifies that the developmental role of XBP1 is indeed linked to an ER-signaling event. An intriguing and extremely novel finding in this study is the link observed between IRE1α and V(D)J recombination during B cell lymphopoiesis. In the absence of IRE1α, the accumulation at the pro–B cell stage of mRNAs for the lymphoid-specific proteins that mediate V(D)J recombination — namely Rag1, Rag2, and TdT — is significantly compromised. None of the obvious suspects — genes that are known to participate in early B cell commitment and developmental progression, such as Ikaros, PU.1, Pax5, EBF, or E2A, were found to be absent or to suffer reduced levels of expression at this stage of development in the absence of IRE1α. In contrast to IRE1α, PERK and XBP1 were not found to be required early in B cell development.

One possible link that might have been considered to exist between the UPR and early B cell development is the phenomenon of heavy chain toxicity. In pre–B cells, a considerable amount of the μ heavy chain protein is misfolded or is incompletely assembled with components of the pre–B cell receptor and is recognized in the ER by specific chaperones, such as Bip, calnexin, and calreticulin. These chaperones retain unassembled and misfolded proteins in the ER, providing these proteins with the opportunity to fold and assemble properly or helping to facilitate their retro-translocation into the cytosol and degradation in proteasomes (16). The notion that Ig heavy chain proteins in the absence of a regular light chain may be toxic to cells (heavy chain toxicity) was first enunciated by George Kohler (17) and is probably linked to signaling resulting in apoptosis that is induced by misfolded proteins in the ER. In has been suggested that pre–B cells are somehow protected from heavy chain toxicity (18), and it might well be that the UPR helps pre–B cells adapt to ER stress and thus permits their survival.

Some of the findings presented by Zhang et al. (15), however, fail to support a connection between the UPR and protection from heavy chain toxicity Although the cytoplasmic tail of IRE1α is required for the expression of Rag and TdT, the catalytic activities of the cytosolic kinase and endoribonuclease domains of IRE1α are not. This suggests that this particular developmental function of IRE1α is unrelated to its activation by misfolded proteins in the ER. The possibility that TRAF2 contributes to the IRE1α-dependent control of early B cell development has been considered by Zhang et al., but since the recruitment of this adaptor by IRE1α depends on the latter’s kinase activity (19), some other unknown kinase-independent biochemical function of IRE1α may need to be invoked. It should be emphasized that while IRE1α may be important during the development of B and possibly T cells, little data exists to link the UPR itself to IRE1α’s role early in B cell ontogeny. IRE1α has already been shown to localize to the inner nuclear membrane, and this might facilitate the ability of IRE1α to regulate gene expression early in B cell development. As Zhang et al. point out, IRE1 in yeast associates with a specific transcriptional activator, and in developing lymphocytes, the vertebrate homolog may possibly function as a molecular scaffold, somehow facilitating the transcription of Rag genes and TdT. There is a growing appreciation of the fact that many genes expressed by lymphocytes are sequestered in the periphery of the nucleus when they are silent (20). The possibility that IRE1α might contribute in some direct or indirect way to the physical localization of the Rag locus and TdT during B cell development probably merits further exploration.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 268.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: ATF6, activating transcription factor 6; CHOP, C/EBP-homologous protein; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; PERK, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase–like ER kinase; TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; UPR, unfolded protein response; XBP1, X-box–binding protein 1.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Mori K, Ma W, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sitia R, Braakman I. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum protein factory. Nature. 2003;426:891–894. doi: 10.1038/nature02262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman RJ. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1389–1398. doi:10.1172/JCI200216886. doi: 10.1172/JCI16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imaizumi K, et al. The unfolded protein response and Alzheimer’s disease. . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001; 1536:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu EJ, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10690–10698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10690.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozcan U, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aridor M, Balch WE. Integration of endoplasmic reticulum signaling in health and disease. Nat. Med. 1999;5:745–751. doi: 10.1038/10466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee K, et al. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002;16:452–466. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, et al. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7499–7509. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen X, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reimold AM, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaffer AL, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang K, et al. The unfolded protein response sensor IRE1α is required at 2 distinct steps in B cell lymphopoiesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:268–281. doi:10.1172/JCI200521848. doi: 10.1172/JCI21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho S, Chaudhuri S, Bacchawat AK, McDonald K, Pillai S. Accelerated proteasomal degradation of membrane immunoglobulin heavy chains. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4713–4719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohler G. Immunoglobulin chain loss in hybridoma lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:2197–2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haas IG, Wabl M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain toxicity in plasma cells is neutralized by fusion to pre-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1984;81:7185–7188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urano F, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosak ST, et al. Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science. 2002;296:158–162. doi: 10.1126/science.1068768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]