Abstract

Background.

In this study we attempted to discern the factors predictive of neurologic death in patients with brain metastasis treated with upfront stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) without whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) while accounting for the competing risk of nonneurologic death.

Methods.

We performed a retrospective single-institution analysis of patients with brain metastasis treated with upfront SRS without WBRT. Competing risks analysis was performed to estimate the subdistribution hazard ratios (HRs) for neurologic and nonneurologic death for predictor variables of interest.

Results.

Of 738 patients treated with upfront SRS alone, neurologic death occurred in 226 (30.6%), while nonneurologic death occurred in 309 (41.9%). Multivariate competing risks analysis identified an increased hazard of neurologic death associated with diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment (DS-GPA) ≤ 2 (P = .005), melanoma histology (P = .009), and increased number of brain metastases (P<.001), while there was a decreased hazard associated with higher SRS dose (P = .004). Targeted agents were associated with a decreased HR of neurologic death in the first 1.5 years (P = .04) but not afterwards. An increased hazard of nonneurologic death was seen with increasing age (P =.03), nonmelanoma histology (P<.001), presence of extracranial disease (P<.001), and progressive systemic disease (P =.004).

Conclusions.

Melanoma, DS-GPA, number of brain metastases, and SRS dose are predictive of neurologic death, while age, nonmelanoma histology, and more advanced systemic disease are predictive of nonneurologic death. Targeted agents appear to delay neurologic death.

Keywords: competing risks, neurologic death, radiosurgery, whole brain radiotherapy.

Recent studies show that approximately 20% of patients with brain metastases treated only with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) die of neurologic causes.1 While the number of patients who die of neurologic death seems to have decreased over time due to the earlier detection of brain metastases.2 those who experience neurologic death commonly suffer from a decline in quality of life, functional independence, and cognitive abilities prior to succumbing to their intracranial disease. In general, neurologic death represents a failure of CNS-directed therapy; thus, rapid neurologic death suggests a failure of upfront CNS-directed therapy.

Importance of the Study

Predicting brain metastasis patient populations at relatively high risk of neurologic death is of significant clinical concern because knowledge of factors predisposing to neurologic death may allow clinicians to better prioritize intracranial versus extracranial therapies. In the current study we have identified factors predictive for neurologic death in patients treated upfront with SRS alone, which should allow for greater individualization of treatment strategies implemented in these patients.

Prospective studies suggest that the use of whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) can decrease the likelihood of neurologic death in the setting of resected solitary brain metastasis3 and unresected brain metastasis when combined with SRS.1 However, the benefit of upfront WBRT must be weighed against the risk of subacute worsening of quality of life4 and chronic worsening of cognition commonly seen with WBRT.5 Several randomized trials have shown that the omission of WBRT from upfront radiosurgical management of patients does not lead to a worse survival.1,6

The use of upfront WBRT for managing patients with brain metastases has declined over time with the publication of multiple randomized trials showing no survival benefit of WBRT over SRS alone.1,6,7 One issue that remains to be addressed is the identification of populations that may still benefit from upfront WBRT. We performed a retrospective single institution analysis of patients managed with upfront SRS to identify predictors of the mutually exclusive competing risks of neurologic and nonneurologic death.

Materials and Methods

Data Acquisition

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The dataset was derived from the Wake Forest Gamma Knife database, wherein patients treated between January 2000 and December 2013 for brain metastases who received upfront SRS without WBRT were identified. Electronic medical records were reviewed to verify patient characteristics and outcomes. Diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment (DS-GPA) was determined based on the parameters set forth by Sperduto et al.8

Patient Follow-up and Endpoint Definitions

Following initial SRS treatment, patients were followed with MRI of the brain and clinical examination at 4–8 weeks postprocedure and then every 3 months thereafter. Neurologic death was defined as previously described by Patchell et al.3 In brief, regardless of the status of extracranial disease, if a patient died with progressive neurologic decline, he or she was determined to have had neurologic death. Also, patients with severe neurologic dysfunction dying from intercurrent disease were considered to have had neurologic death.

Radiosurgical Technique

Patients were treated with single fraction SRS using the Leksell Gamma Knife B, C, or Perfexion units (Elekta AB, Stockholm). Prior to radiosurgical treatment, patients underwent high-resolution stereotactic MRI of the brain. Treatment planning was performed on the Leksell GammaPlan Treatment Planning System (Elekta AB, Stockholm). A median dose of 19 Gy (interquartile range, 17–21 Gy) was prescribed to the 50% isodose line for each lesion. The prescribed dose was generally based upon recommendations set forth by Shaw et al;9 however, a decrease in margin dose was used at physician discretion based upon the size of the lesion and where this size fell within the ranges as tolerable for a given dose.

Statistical Analysis

Median follow-up and time-to-event outcomes were defined as the time from SRS to the time of the most recent follow-up or the event of interest. Time-to-event outcomes were summarized using the Kaplan-Meier estimator with log-rank tests performed for stratified outcomes. Median follow-up time was estimated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Patients who were either alive or deceased with an established cause of death were included in the subsequent competing risks analysis. Deceased patients for whom the cause of death could not be determined were excluded. Cumulative incidences of neurologic and nonneurologic death were estimated using Fine and Gray’s methodology.10 Competing risks models were developed to estimate the single variable subdistribution HRs associated with each predictor. Putative predictor variables for which univariate analyses were performed included age, sex, ethnicity, DS-GPA, KPS, primary site, primary histology, number of brain metastases, presence of brainstem metastases, systemic disease status (stable vs progressive), systemic disease burden, lowest SRS dose, and the use of targeted therapies. Statistically significant (P<.05) variables identified on UVA were included in forward stepwise regressions to identify the multivariable models that minimized Akaike’s information criterion (AIC).11 These results were used to guide purposeful development of multivariate competing risks models for both neurologic and nonneurologic death. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.2.1 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Survival Outcomes

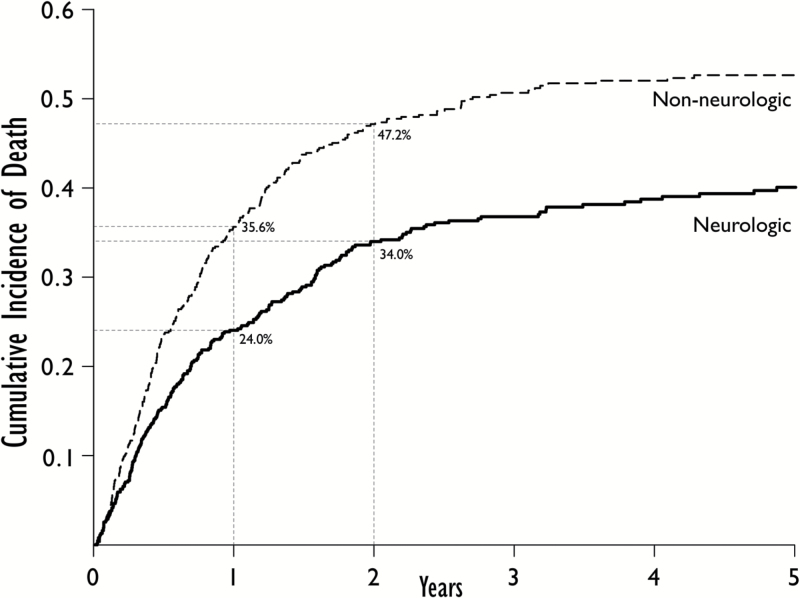

A total of 738 patients were identified that met study criteria. The characteristics of these patients can be found in Table 1. Median follow-up was 53.9 months (95% CI, 45.3–75.5 mo). Of 738 patients treated with upfront SRS alone, 95 (12.9%) patients were alive, and 643 (87.1%) patients were deceased at the time of analysis. Of all deceased patients, the cause of death was neurologic in 226 (35.1%), nonneurologic in 309 (48.1%), and unknown in 108 (16.8%). A total of 630 patients were either alive or had known cause of death and were subsequently included in the competing risks analysis. The one-year and two-year cumulative incidences for all-cause mortality were 59.6% and 81.2%, respectively. The one- and two-year cumulative incidences for neurologic death were 24.0% and 34.0%, while the one- and two-year cumulative incidences for nonneurologic death were 35.6% and 47.2%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 738 patients initially treated with upfront SRS alone.

| n (%/IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Total | 738 |

| Age, y, median | 62 (53–70) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 342 (46.3) |

| Male | 396 (53.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 654 (88.6) |

| African American | 72 (9.8) |

| Hispanic | 8 (1.1) |

| Other | 4 (0.5) |

| Primary Site | |

| Breast | 102 (13.8) |

| HER2 + | 46 (45.1) |

| HER2 - | 45 (44.1) |

| HER2 unknown | 11 (10.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 61 (8.3) |

| Lung | 364 (49.3) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 216 (59.3) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 57 (15.7) |

| Other | 91 (25.0) |

| Melanoma | 117 (15.9) |

| BRAF + | 11 (9.4) |

| BRAF - | 11 (9.4) |

| BRAF unknown | 95 (81.2) |

| RCC | 68 (9.2) |

| Other | 26 (3.5) |

| Number of brain metastases | |

| 1 | 373 (50.5) |

| 2 | 170 (23.0) |

| 3 | 94 (12.7) |

| 4+ | 101 (13.7) |

| Presence of brainstem metastasis | 23 (3.1) |

| Extent of systemic disease | |

| None | 115 (15.6) |

| Oligometastasis | 254 (34.4) |

| Widespread metastasis | 224 (30.3) |

| Unknown | 37 (5.0) |

| Systemic disease status | |

| Stable | 399 (54.1) |

| Progressive | 264 (35.8) |

| Unknown | 74 (10.0) |

| KPS | |

| ≤ 70% | 183 (24.8) |

| 80% | 320 (43.4) |

| 90%–100% | 234 (31.8) |

| DS-GPA | |

| 0–1 | 159 (22.3) |

| 1.5–2 | 293 (41.0) |

| 2.5–3 | 218 (30.5) |

| >3 | 44 (6.2) |

| Lowest SRS dose, median | 19.0 (17.0–21.0) |

Abbreviations: DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IQR, interquartile range; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SRS,stereotactic radiosurgery.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidences of neurologic and nonneurologic death with one- and two-year cumulative incidences for each event labeled.

Predictors of Neurologic and Nonneurologic Death

Multivariate competing risks analysis identified an increased hazard of neurologic death associated with DS-GPA ≤2 (P=.005), lowest SRS dose (P =.004), melanoma histology (P=.009), and increasing number of brain metastases (P<.001). An increased hazard of nonneurologic death was seen with increasing age (P=.03), nonmelanoma histology (P<.001), presence of systemic/extracranial disease (P<.001), and progressive systemic disease (P<.001). Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multivariate proportional subdistribution hazard models for the competing risks of neurologic and nonneurologic death.

| Neurologic death | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI | P value | |

| DS-GPA ≤ 2 | 1.54 | 1.14–2.08 | .005 |

| Lowest SRS dose (continuous) | 0.93 | 0.89–0.98 | .004 |

| Melanoma histology | 1.63 | 1.13–2.34 | .009 |

| Number of brain metastases (continuous) | 1.10 | 1.05–1.16 | <.001 |

| Nonneurologic death | |||

| HR | CI | P value | |

| Age (continuous) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | .03 |

| Nonmelanoma histology | 2.00 | 1.38–2.91 | <.001 |

| Presence of extracranial disease | 1.86 | 1.30–2.66 | <.001 |

| Progressive systemic disease | 1.47 | 1.13–1.90 | .004 |

Abbreviations: CI, 95% confidence interval; DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment, HR, hazard ratio; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery.

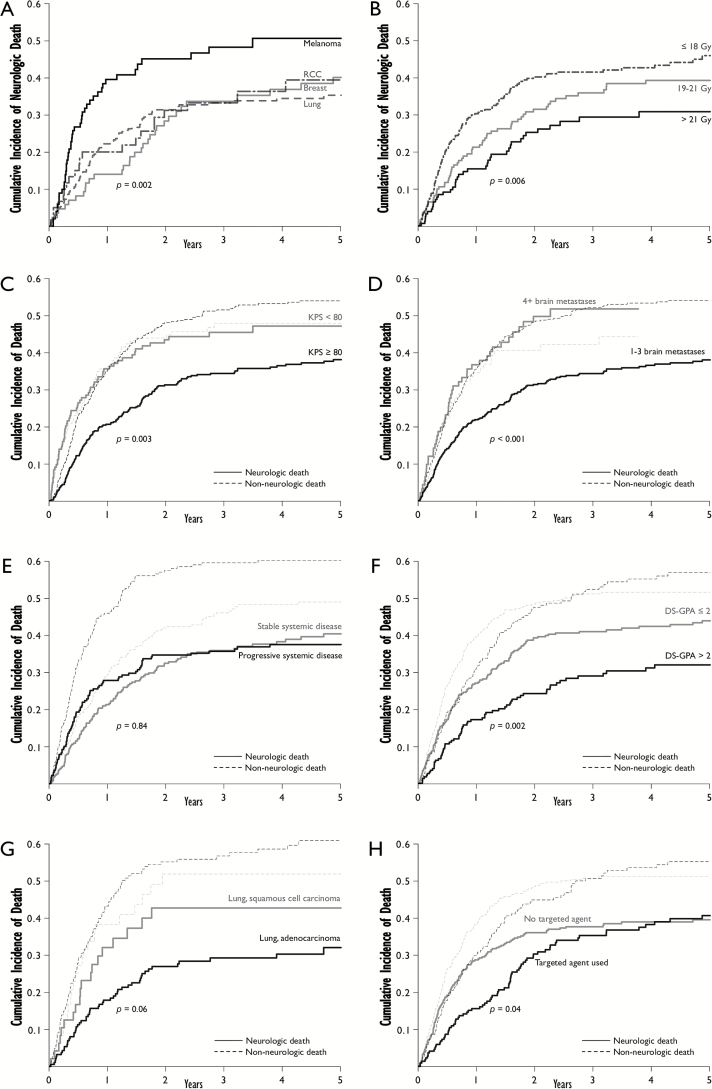

Stratified Cumulative Incidences of Neurologic and Nonneurologic Death

The cumulative incidences of neurologic and nonneurologic death were further explored and were stratified by variables found to have HRs predictive of either event (Fig. 2). Melanoma was associated with higher rates of neurologic death as compared with nonmelanoma histology (Fig. 2A). The lowest SRS dose received to a brain metastasis had a significant effect on the cumulative incidence of neurologic death that was most apparent when stratifying by the doses in Fig. 2B. Patients with KPS<80% had similar cumulative incidences of neurologic versus nonneurologic death, while patients with KPS≥80% had lower cumulative incidences of neurologic versus nonneurologic death as well as lower neurologic death versus KPS<80 patients (Fig. 2C). Patients with 4+ brain metastases also had cumulative incidences of neurologic death similar to that of nonneurologic death, which was significantly higher than that seen in patients with 1–3 brain metastases (Fig. 2D). Patients with progressive systemic disease had higher incidence of nonneurologic death versus those with stable systemic disease, with no difference in cumulative incidence of neurologic death (Fig. 2E). In lung cancer patients, there was a trend towards higher cumulative incidence of neurologic death with squamous cell carcinoma versus adenocarcinoma; however, this was not statistically significant (P =.06) (Fig. 2G). The cumulative incidence of neurologic death was similar for patients receiving cavity-directed SRS as compared with those who did not (P=.24); however, the incidence of nonneurologic death was lower for patients receiving cavity-directed SRS. Stratified one- and two-year cumulative incidences for neurologic and nonneurologic death are reported in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Stratified cumulative incidences. 2A-B: Neurologic death stratified by primary malignancy (A) and lowest stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) dose (B). 2C-H: Neurologic and nonneurologic death stratified by KPS (C), number of brain metastases (D), systemic disease status (E), diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment (DS-GPA), (F), lung histology (G), and the use of targeted therapies (H). All reported P values are for stratifications for neurologic death (rather than nonneurologic death). Abbreviations: DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery.

Table 3.

Cumulative incidences of neurologic and nonneurologic death at one and two years as stratified by clinical variables of interest.

| Neurologic Death | Nonneurologic Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year CI (%) | 2-year CI (%) | P value | 1-year CI (%) | 2-year CI (%) | P value | |

| Histology | .002 | .02 | ||||

| Melanoma | 39.5 | 45.1 | 29.4 | 34.7 | ||

| Nonmelanoma | 29.5 | 34.7 | 36.8 | 49.4 | ||

| KPS | .003 | .70 | ||||

| <80% | 35.5 | 43.4 | 36.3 | 43.8 | ||

| 80%–100% | 20.6 | 31.2 | 35.3 | 48.0 | ||

| Brain metastases | <.001 | .32 | ||||

| 1–3 | 21.9 | 32.3 | 35.8 | 48.2 | ||

| 4+ | 36.6 | 49.7 | 34.6 | 40.6 | ||

| Lowest SRS dose | .006 | .02 | ||||

| ≤ 18 Gy | 30.3 | 40.1 | 30.7 | 41.6 | ||

| 19–21 Gy | 21.2 | 31.4 | 35.9 | 48.7 | ||

| > 21 Gy | 15.3 | 25.2 | 44.1 | 55.6 | ||

| Cavity-directed SRS | .24 | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 27.2 | 36.9 | 21.6 | 34.8 | ||

| No | 22.9 | 32.9 | 40.5 | 51.4 | ||

| Extent of systemic disease | .28 | <.001 | ||||

| None | 28.3 | 38.7 | 15.9 | 28.9 | ||

| Oligometastasis | 23.2 | 32.9 | 37.3 | 51.6 | ||

| Widespread metastasis | 23.5 | 32.9 | 44.8 | 53.0 | ||

| Systemic disease status | .84 | <.001 | ||||

| Stable | 21.3 | 32.4 | 29.5 | 41.9 | ||

| Progressive | 27.8 | 34.7 | 45.9 | 57.5 | ||

| Lung histology | .06 | .44 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 17.8 | 26.9 | 43.2 | 55.1 | ||

| SqCC | 32.0 | 42.7 | 38.2 | 52.8 | ||

| Targeted therapy | .04* | .60 | ||||

| Yes | 15.6 | 30.3 | 30.3 | 44.9 | ||

| No | 28.7 | 36.0 | 38.6 | 48.4 | ||

| DS-GPA | .002 | .19 | ||||

| 0–1 | 36.0 | 46.7 | 39.3 | 45.2 | ||

| 1.5–2 | 22.3 | 35.4 | 39.8 | 49.9 | ||

| 2.5–3 | 17.7 | 23.1 | 32.8 | 49.7 | ||

| >3 | 14.5 | 30.1 | 23.2 | 35.6 | ||

Abbreviations: CI, cumulative incidence; DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; SqCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery.

*This P value corresponds to the initial 1.5 years following SRS; over the entire 5-year post-SRS period, P = 0.25.

Effect of Targeted Agents

Of the 630 patients analyzed, 221 (35.1%) received systemic treatment with a small molecule or monoclonal antibody targeting a specific mutation or pathway during or within 30 days of receiving SRS. The one-year cumulative incidence of neurologic death for patients who received a targeted agent was 23.5% versus 35.4% for patients who did not receive a targeted agent (P =.04) (Fig. 2H). The benefit of targeted therapy began to diminish at approximately 1.5 years, and at 4 years the cumulative incidence of neurologic death was similar for patients who received targeted therapy (38.2%) as compared with those who did not (38.9%). The HR associated with the use of targeted therapy was thus not statistically significant over the entire 5-year post-SRS period (HR, 0.85; CI, 0.66–1.12; P=.25) but was a statistically significant predictor of neurologic death in the initial 1.5 years following SRS (HR, 0.70; CI, 0.50–0.97; P=.04).

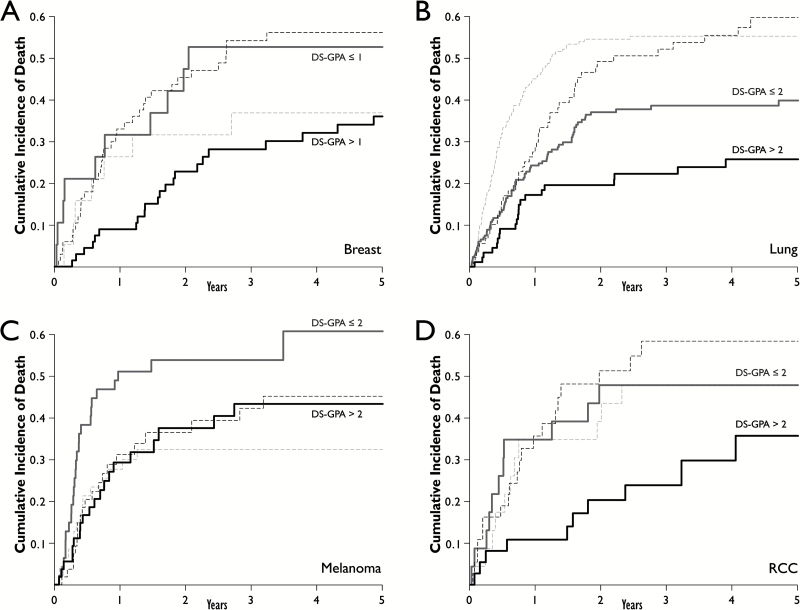

DS-GPA

Patients were analyzed by subset to determine the effect of DS-GPA on neurologic death for each of the most common primary malignancies. An increased HR for neurologic death was seen with decreasing DS-GPA for patients with breast cancer (P=.02), lung cancer (P=.03), melanoma (P=.04), and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (P=.05). Fig. 3 depicts the cumulative incidences of neurologic and nonneurologic death as stratified by DS-GPA for each of these primary malignancies. No association was seen for gastrointestinal sites (P=.38). Univariate DS-GPA models were compared with models that included the individual component variables used to calculate DS-GPA for each respective primary malignancy. AIC values were found to be very similar between the composite DS-GPA models and the models that included the individual component variables.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative incidences of neurologic death (solid lines) and nonneurologic death (dashed lines) as stratified by DS-GPA for breast (A), lung (B), melanoma (C), and RCC (D). Abbreviations: DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Historically, the brain metastasis population has included large numbers of patients with symptomatic brain metastases.12 With the advent of improved imaging modalities and improved screening guidelines, however, this population has evolved to now consist predominantly of patients with occult and asymptomatic brain metastases,2,13 with lower incidences of neurologic death.2,14,15 In the recent phase III EORTC 22952 study of WBRT versus observation after surgery or SRS for brain metastases, 28% of patients experienced neurologic death in the arm of the trial receiving WBRT.1 Some series, however, have continued to report rates of neurologic death as high as 50–75% in particularly high-risk populations.16–18 Factors previously identified that predispose brain metastasis patients to neurologic death include radioresistant histology,16 intratumoral hemorrhage,17 brainstem location,19,20 and the lack of WBRT.1,3 In the present study, we attempted to determine factors that may predict neurologic death in the population that has not received WBRT using a competing risks model to characterize high-risk populations more accurately.

Although WBRT has previously been shown to decrease the risk of neurologic death after surgical resection,3 recent trends in practice have favored the use of cavity-directed SRS to avoid the toxicities of WBRT while maintaining local control at the site at highest risk for failure. In a series by Jensen et al, however, neurologic death occurred in 50% of patients receiving SRS to the brain metastasis resection cavity at one year.18 The study by Jensen et al did not account for the competing risk of nonneurologic death, however, likely resulting in inflation of neurologic death estimates due to significant censoring. When accounting for the competing event of nonneurologic death, the results of the present study suggest that the cumulative incidence of neurologic death was statistically similar at one year for patients who received cavity-directed SRS (27.2%) as compared with those who did not (22.9%). This finding highlights the importance of the use of competing risks analysis when evaluating mutually exclusive, high incidence survival outcomes.

Radioresistant histologies such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma represent populations in which SRS may play a role in mitigating neurologic death. A retrospective series by Wronski et al found a 75% rate of neurologic death in patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with WBRT;16 however, more recent SRS series have reported a rate of neurologic death in the renal cell carcinoma brain metastasis population closer to 25%.21 For radioresistant brain metastases, patients who receive SRS may have a lower incidence of neurologic death due to the ability of SRS to locally control brain metastases. The results of the present study suggest that renal cell carcinoma has a relatively low one-year incidence of neurologic death (20.0%) with upfront SRS alone. Unfortunately, the one-year incidence of neurologic death for melanoma patients was 39.5%, suggesting the need for improvement. As melanoma patients have high rates of distant brain failure and intratumoral hemorrhage,17,22 it is possible that these factors may negate the advantage of improved local control afforded by SRS.

The present study has identified several novel predictors of neurologic death, including lowest SRS dose to the tumor margin, KPS, DS-GPA, and targeted agent use. As patients in this study were consistently prescribed SRS doses based upon tumor volume constraints set forth by RTOG 90-05,9 the lowest SRS dose is an inversely proportional surrogate for tumor volume. Larger volume brain metastases have been implicated in worsening survival in prior series, and we interpret the association between lowest SRS dose and neurologic death in the current study as confirming that larger tumors contribute to neurologic death23 as opposed to being a measure of correspondingly large burdens of extracranial disease. KPS and number of brain metastases were also predictive of neurologic death, as was DS-GPA, the calculation of which is highly reliant on these variables. With the knowledge that DS-GPA is predictive of neurologic death, clinicians may now simultaneously estimate overall prognosis as well as risk of neurologic death with this single composite endpoint.

The clinical utility of the present study lies in the identification of populations for which CNS-directed therapies ultimately fail to prevent neurologic death. For these identified populations at high risk of neurologic death with SRS alone, escalation of CNS-directed therapies may be appropriate, with options including dose escalation with staged SRS,24 use of combined modality intracranial therapy (surgery + SRS or WBRT + SRS), and also concurrent targeted therapies,25 as targeted agents were found in the present study to mitigate or at least delay neurologic death.

There are several limitations of this current study. As a retrospective analysis, it is subject to patient selection bias, and thus its primary role is to generate hypotheses. While the patient population is large, data were collected over a 13-year interval during which significant changes occurred in the management of multiple cancer histologies. Prospective validation is necessary to confirm the findings of the current study—if validated, however, these findings could represent a useful tool to risk-stratify patients by the likelihood of failing initial CNS-directed therapies.

Conclusion

Melanoma histology, lower DS-GPA, greater number of brain metastases, and larger metastases appear to predict neurologic death. The use of targeted therapies appears to delay neurologic death and may be a worthwhile consideration for patients eligible for these therapies and at high risk of this event, although clinical studies are required to validate these results.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Conflicts of Interest statement. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952–26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lester SC, Taksler GB, Kuremsky JG, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of patients with brain metastases based on symptoms: an argument for routine brain screening of those treated with upfront radiosurgery. Cancer. 2014;120(3):433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soffietti R, Kocher M, Abacioglu UM, et al. A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial of adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation in patients with one to three brain metastases from solid tumors after surgical resection or radiosurgery: quality-of-life results. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greene-Schloesser D, Robbins ME, Peiffer AM, Shaw EG, Wheeler KT, Chan MD. Radiation-induced brain injury: A review. Front Oncol. 2012;2:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2483–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sperduto PW, Chao ST, Sneed PK, et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(3):655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, et al. Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol 90-05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(2):291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Earnest F, 4th, Ryu JH, Miller GM, et al. Suspected non-small cell lung cancer: incidence of occult brain and skeletal metastases and effectiveness of imaging for detection--pilot study. Radiology. 1999;211(1):137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Niwińska A, Tacikowska M, Murawska M. The effect of early detection of occult brain metastases in HER2-positive breast cancer patients on survival and cause of death. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(4):1134–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vern-Gross TZ, Lawrence JA, Case LD, et al. Breast cancer subtype affects patterns of failure of brain metastases after treatment with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2012;110(3):381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wrónski M, Maor MH, Davis BJ, Sawaya R, Levin VA. External radiation of brain metastases from renal carcinoma: a retrospective study of 119 patients from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37(4):753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neal MT, Chan MD, Lucas JT, Jr, et al. Predictors of survival, neurologic death, local failure, and distant failure after gamma knife radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6):1250–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jensen CA, Chan MD, McCoy TP, et al. Cavity-directed radiosurgery as adjuvant therapy after resection of a brain metastasis. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(6):1585–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucas JT, Jr, Colmer HG, 4th, White L, et al. Competing Risk Analysis of Neurologic versus Nonneurologic Death in Patients Undergoing Radiosurgical Salvage After Whole-Brain Radiation Therapy Failure: Who Actually Dies of Their Brain Metastases? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(5):1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kilburn JM, Ellis TL, Lovato JF, et al. Local control and toxicity outcomes in brainstem metastases treated with single fraction radiosurgery: is there a volume threshold for toxicity? J Neurooncol. 2014;117(1):167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cochran DC, Chan MD, Aklilu M, et al. The effect of targeted agents on outcomes in patients with brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma treated with Gamma Knife surgery. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(5):978–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ayala-Peacock DN, Peiffer AM, Lucas JT, et al. A nomogram for predicting distant brain failure in patients treated with gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery without whole brain radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(9):1283–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baschnagel AM, Meyer KD, Chen PY, et al. Tumor volume as a predictor of survival and local control in patients with brain metastases treated with Gamma Knife surgery. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(5):1139–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Devoid H-M, McTyre ER, Page BR, Metheny-Barlow L, Ruiz J, Chan MD. Recent advances in radiosurgical management of brain metastases. Front Biosci. 2016;8:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson AG, Ruiz J, Hughes R, et al. Impact of systemic targeted agents on the clinical outcomes of patients with brain metastases. Oncotarget. 2015;6(22):18945–18955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]