Abstract

Background.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an aggressive brain cancer with a poor prognosis. The use of immune therapies to treat GBM has become a promising avenue of research. It was shown that amphotericin B (Amp B) can stimulate the innate immune system and suppress the growth of brain tumor initiating cells (BTICs). However, it is not feasible to use histopathology to determine immune activation in patients. We developed an MRI technique that can rapidly detect a therapeutic response in animals treated with drugs that stimulate innate immunity. Ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles (USPIOs) are MRI contrast agents that have been widely used for cell tracking. We hypothesized that the increased monocyte infiltration into brain tumors due to Amp B can be detected using USPIO-MRI, providing an indicator of early drug response.

Methods.

We implanted human BTICs into severe combined immunodeficient mice and allowed the tumor to establish before treating the animals with either Amp B or vehicle and then imaged them using MRI with USPIO (ferumoxytol) contrast.

Results.

After 7 days of treatment, there was a significantly decreased T2* in the tumor of Amp B but not vehicle animals, suggesting that USPIO is carried into the tumor by monocytes. We validated our MRI results with histopathology and confirmed that Amp B–treated animals had significantly higher levels of macrophage/microglia that were colocalized with iron staining in their brain tumor compared with vehicle mice.

Conclusion.

USPIO-MRI is a promising method of rapidly assessing the efficacy of anticancer drugs that stimulate innate immunity.

Keywords: drug response, glioblastoma, innate immunity, iron oxide, MRI.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is one of the most aggressive brain cancers, with a bleak prognosis.1 It has been suggested that this poor prognosis is due to brain tumor initiating cells (BTICs), which are chemo- and radiation-resistant stemlike cells.2 It is known that many types of cancer, including BTICs of GBM, secrete factors that polarize blood-borne monocytes into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) with an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and utilize them to promote tumor growth.3–5

There have been 2 main approaches to target TAMs for the treatment of cancer. As TAMs promote tumor survival and enhance tumor progression, ablating macrophages to yield therapeutic benefits is one approach. In this regard, treatment with a colony stimulating factor (CSF)-1 receptor kinase inhibitor can decrease TAMs and reduce tumor growth while prolonging survival.6 Therapeutic benefits can also be achieved by reprogramming compromised monocyte/macrophage into a pro-inflammatory phenotype that infiltrates into the brain and suppresses the tumor. This can be achieved by antagonizing the CSF-1 receptor7 or with application of an immune stimulator such as amphotericin B (Amp B).2

Monocyte infiltration into brain parenchyma is typically mediated by a series of molecules lining the endothelial wall of the blood vessel. Monocytes initiate this process by undergoing tethering and rolling via interaction with selectin ligands such as P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1.21 The rolling on the vascular wall reduces the velocity of monocytes, allowing them to interact with chemokines to activate G protein coupled receptor and increase their affinity to endothelium via the integrin class of molecules. The increased affinity of monocytes to cell adhesion molecules present on the endothelial cells facilitates the arrest of the movement of monocytes. Monocytes are guided to enter the CNS by the chemoattractant chemokine C-C ligand 2.22 Then, with the help of proteases such as the matrix metalloproteinases, monocytes can cross the glia limitans and enter the CNS.23

Amp B significantly increases the amount of pro-inflammatory monocytes in a mouse model of GBM to control tumor growth.2 Moreover, tumor suppression via cell cycle arrest of transformed cells is the primary mechanism of Amp B‒stimulated circulating monocytes, which is different from the many cytotoxic therapies that actively kill transformed cells.2 Hence, it may take longer to observe a decrease in tumor volume when stimulators of innate immune response such as Amp B are used compared with cytolytic therapies.

Monocytes are crucial in the mechanism by which Amp B promotes the lifespan of mice harboring intracranial glioblastoma, as depleting monocytes with clodronate liposomes abrogates its therapeutic effect.2 Thus, monitoring the trafficking of these populations of immune cells into the tumor mass may provide a faster way of detecting an innate immune system–related drug response than waiting for changes in tumor volume or lifespan of animals. As monocytes are phagocytic cells, they engulf iron particles. This makes it possible for ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles (USPIOs)8 to be used as an MRI contrast agent to detect trafficking of monocytes into tumor mass.

Iron oxide nanoparticles have an iron core coated with dextran or ferucarbotran to reduce its toxicity and facilitate cellular uptake.9 Once injected into the blood stream, USPIOs are cleared from the plasma by the reticulo-endothelial system via receptor endocytosis.8 USPIOs are typically phagocytosed and stored by circulating monocytes and by cells in the liver as well as bone marrow.

USPIO-MRI is a promising tool to non-invasively track monocytes, since iron oxide nanoparticles have been widely used in humans. Feridex, a larger iron oxide nanoparticle, is an FDA approved contrast agent for liver imaging.10,11 Although there has been no FDA approved USPIO as a contrast agent, ferumoxytol is used to treat anemia in patients with end-stage renal failure.12,13 Due to its low toxicity, USPIOs have been widely used to study immune cells in other contexts, such as multiple sclerosis14,15 and stroke.16 This wide range of clinical use should enable animal USPIO results to be easily translatable to humans.

We hypothesize that we can use USPIO-MRI to label monocyte trafficking into the region of a brain tumor. This should be able to detect the treatment-associated phenomena of drugs that modulate the innate immune system. To do this, we used Amp B as the test drug, since our previous work has already demonstrated the efficacy of Amp B in reducing GBM growth in mice through stimulating innate immunity.2 Using an animal model with intracranial GBM and Amp B as the drug, we are the first to show that USPIO imaging can be used to rapidly detect a treatment-associated phenomenon due to activation of the innate immune system.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Ethics were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Calgary. Female severe combined immunodeficient mice (8–10wk, Charles River, CB17 strain) were implanted with 10000 cells of the BT048 BTIC line. This patient-derived BTIC line was described previously2,17; cells were implanted into the right striatum.17 The cell line was tested for pathogen and mycoplasma at Charles River and was obtained from the Clark H. Smith Brain Tumor Bank in 2010. We conducted 2 experiments to address our hypothesis. For both experiments, cells were allowed to grow for 35 days, after which the animals were treated daily as guided by previous results.2 For Experiment 1, animals were treated with 0.2mg/kg Amp B (n=4) or sodium deoxycholate (n=5), the vehicle for Amp B. For Experiment 2, all animals were treated with Amp B (n=4).

MRI Protocol

For both experiments, MRI was performed 42–45 days post-implantation using a 9.4T Bruker system with a 35-mm volume coil. Animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, 30% oxygen, and 70% nitrogen. Three baseline sequences were acquired: T2 weighted (T2w) spin echo (repetition time [TR] = 3000ms, nominal echo time [TE] = 30ms, voxel size = 0.075mm × 0.075mm × 0.5mm), multiecho gradient echo (MEGE) (TR = 1500ms, TE = 3.1, 7.1, 11.1, 15.1, 19.1ms; voxel size =0.15mm × 0.15mm × 0.75mm, flip angle = 30degrees), and T1 weighted (T1w) scan (TR = 500ms, nominal TE = 7ms, voxel size = 0.15mm × 0.15mm × 0.75mm). The slices from these 3 scans were coregistered. A cannula was then placed into the tail vein through which gadolinium (Gd; Magnevist) was injected at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg as a 100-μL bolus. The T1w scan was then repeated to assess blood‒brain barrier (BBB) leakage. Following the T1w scan, ferumoxytol (30mg/kg) was injected as a 100-μL bolus through the same cannula. The MEGE and T1w sequences were repeated 24 hours post ferumoxytol injection.

Histology

For Experiment 1, animals were immediately sacrificed after MRI and were perfused with phosphate buffered saline and then 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and were paraffin embedded. Tissues were cut into 8-μm paraffin slices; 3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (DAB)-enhanced Perl’s stain18 was used to visualize for iron, and Iba1 immunohistochemistry was used to visualize monocytes that infiltrated the tumor (macrophages).2 We quantified the amount of Iba1 staining in the vehicle as well as the Amp B group by manually counting the number of cells using ImageJ. All the corners of the tumors were used in the cell counting to prevent selection bias. The number of cells within the field of view was normalized to the size of the tumor in that field of view.

For Experiment 2, we injected 100 µL of 500kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–dextran at 50mg/mL into the tail vein of the animals after the MRI. The FITC was allowed to circulate in the body for 1 hour before the mouse was sacrificed. The brains were removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and then placed in 30% sucrose for 48 hours. The brain was then frozen and cut into 20-μm slices. The integrity of tumor and normal appearing brain blood vessels were examined and compared against each other under a fluorescence microscope.

MRI Data Analysis

Tumor volume was calculated manually using the T2w image with the ImageJ software. BBB breakdown was assessed quantitatively by taking the ratio of the signal intensity of the tumor and the signal intensity of the contralateral cortex for both the pre- and post- Gd image and then subtracting the two. Both vehicle as well as Amp B animals showed similar degrees of Gd enhancement on T1w images. T2* is sensitive to molecules that perturb the magnetic field (and are paramagnetic), such as Fe2+. Using the MEGE sequence, we calculated the T2* of the water within the entire tumor, as well as contralateral normal appearing tissue before and after ferumoxytol. Changes in T2* within the tumor were calculated by subtracting the pre-iron value from the post-iron value (obtained 24h post-iron injection). Due to the lack of tumor contrast on the MEGE sequence, the T2w sequence was used as a guide to draw the region of interest in the tumor. The change in T2* post-iron contrast was calculated as post-ferumoxytol T2* minus pre-ferumoxytol T2*. Changes in T2* for vehicle- or Amp B–treated animals were compared using Student’s t-test.

Results

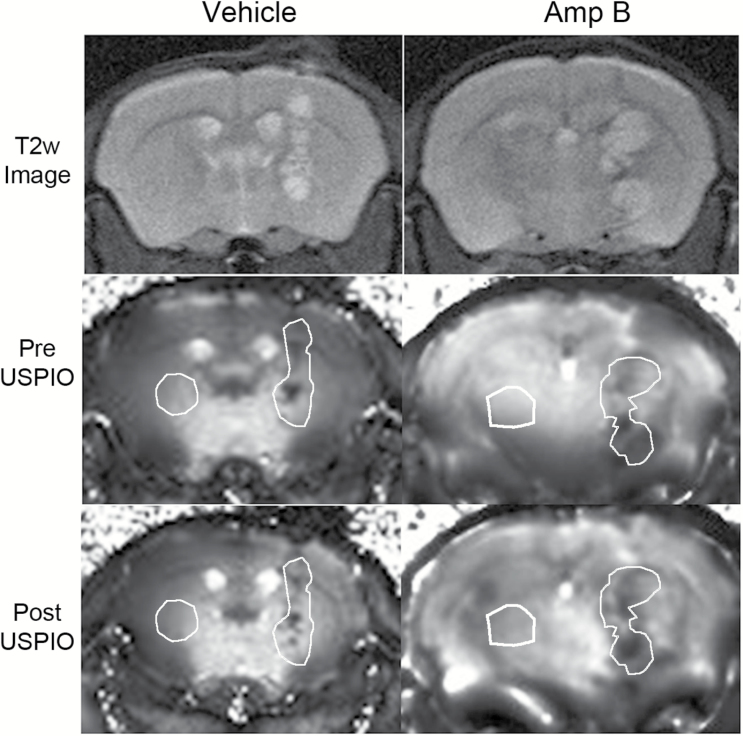

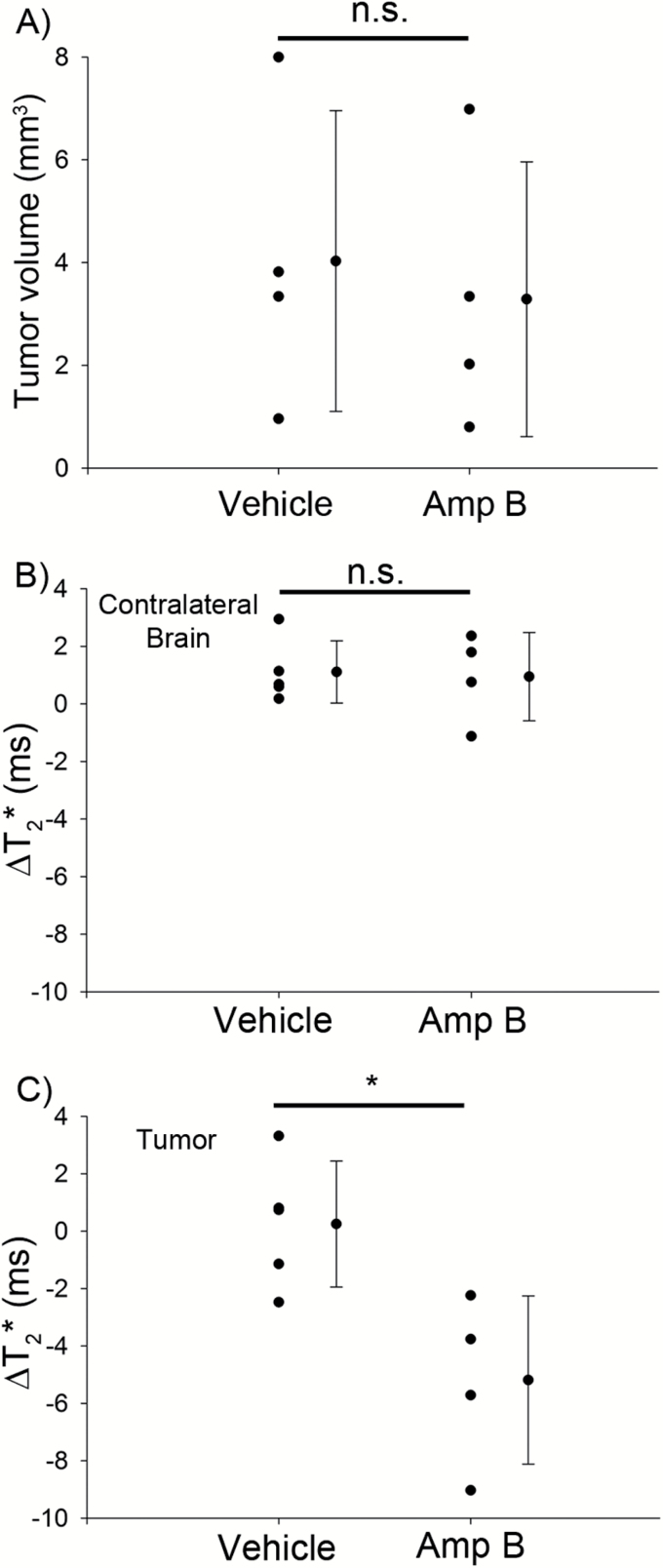

Animals in the vehicle group showed no obvious darkening, while those in the Amp B group had visually apparent darkening (Fig. 1A–D). Using a region of interest that included the visible tumor, T2* values were compared in animals pre- and 24h postcontrast injection. Animals in the vehicle group showed no significant changes in T2* before and after USPIO (P>.05, paired t-test), while the Amp B–treated animals showed significantly decreased T2* compared with pre-injection (P<.01, paired t-test). Figure 2 shows the average change in both tumor volume and T2* when comparing the Amp B group against the vehicles. The decline in tumor T2* in Amp B–treated animals shows that there is likely an increased accumulation of iron in the tumor 24 hours after USPIO injection. There were no significant changes in T2* values on the contralateral side of the brain in the Amp B– or vehicle-treated animals.

Fig. 1.

Changes on the T2* map 24 hours after USPIO injection. There was no significant T2* darkening in the tumor of vehicle animals, but significant darkening in the tumor can be seen in Amp B–treated animals. The white region of interest demarcates the region of interest used for the tumor and the contralateral brain.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of tumor volume and T2* changes in vehicle- and Amp B–treated animals. (A) There was no significant difference in the tumor volume between vehicle- and Amp B–treated animals; this is likely because Amp B treatment occurred for only 7 days in mice with large, established tumors. (B) T2* measured in the brain contralateral to the tumor. There were no significant changes in contralateral brain T2* in the vehicle- and Amp B–treated animals. (C) T2* measured in the tumor. Amp–B treated animals showed a significant reduction in tumor T2* compared with tumor T2* of the vehicle group. *P<.05, Student’s t-test.

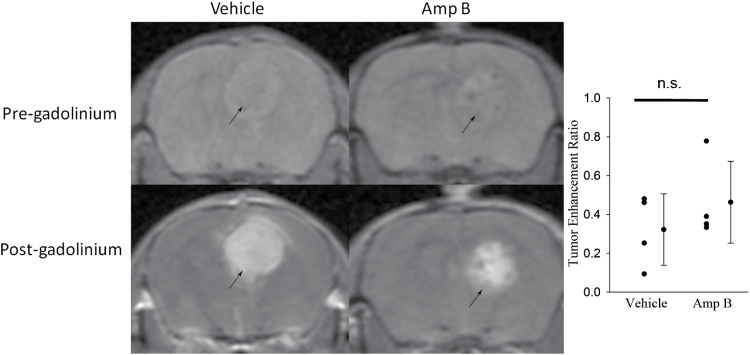

To rule out the possibility that the difference in T2* with Amp B reflects an opening of the BBB that may not exist in the vehicle group, we included a Gd-enhanced MRI study. There was significant BBB leakage in both vehicle- as well as Amp B–treated animals. Examining the normal appearing brain parenchyma, there were no signs of Gd leakage into the tissue (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

T1w rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence (TR = 500ms, nominal TE = 7ms, RARE factor = 4) before and after Gd (Magnevist), showing that vehicle animals had similar degrees of Gd enhancement compared with Amp B–treated animals. Black arrows denote the location of the tumor.

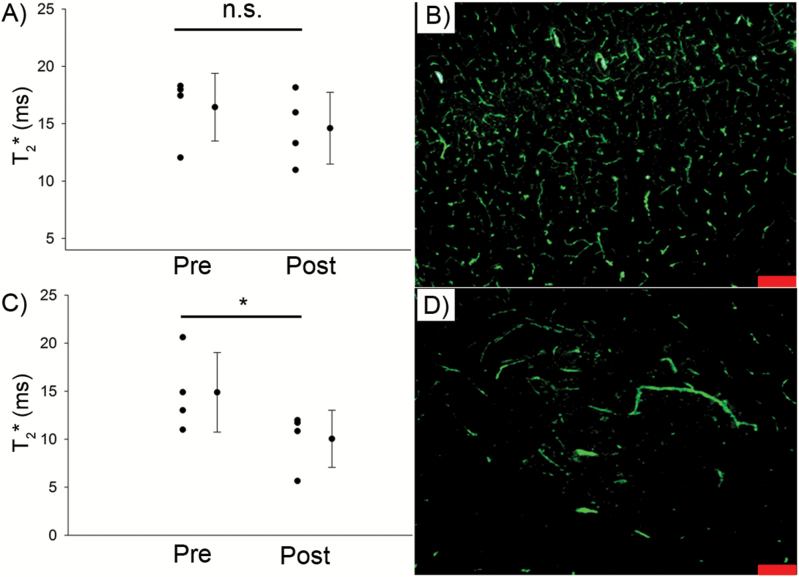

Gadolinium is 950Da, so it is sensitive to relatively small disruptions in the BBB; however, it is possible that Amp B caused a large disruption in the tumor BBB. We tested this possibility using large, 500kDa FITC-dextran molecules that are slightly smaller than ferumoxytol, which is 750kDa. We found that the blood vessels in the apparently normal brain parenchyma are well defined and comparable to those found in the tumor (Fig. 4B and D), suggesting that there is likely very little FITC leakage from the tumor vasculature. In these mice, we replicated our results and showed a decrease in tumor T2* that was similar in magnitude to ones reported in Experiment 1 (Fig. 4A and C).

Fig. 4.

Amp B‒induced decrease in T2* post ferumoxytol contrast is not associated with a leaky BBB. There was a significant decline in T2* post ferumoxytol in the tumor of Amp B–treated animals (C), but not on the contralateral side (A). Fluorescence imaging with FITC revealed similar leakiness of the vasculature in the tumor (D) compared with the contralateral healthy brain (B). Scale bars represent 100 μm. *P<.05, paired t-test.

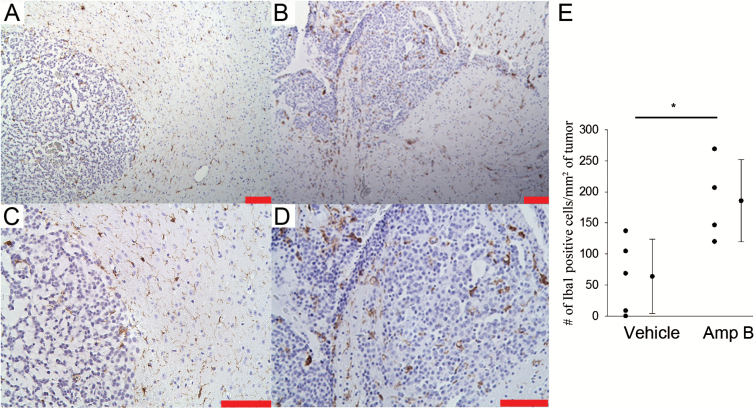

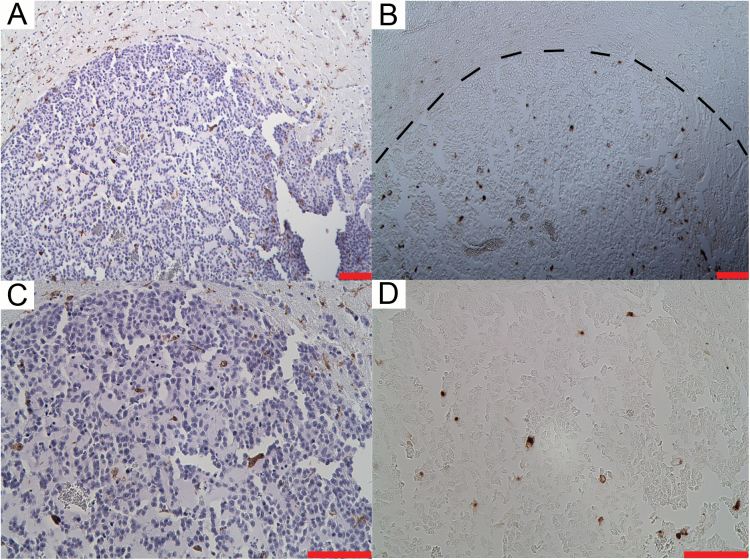

We further validated our MRI results with histopathology by staining for infiltrated monocytes (macrophage) using Iba1, and by staining for iron using DAB-enhanced Perl’s stain. The vehicle group showed minimal Iba1 staining within the tumor tissue, but there was abundant staining outside the tumor mass (Fig. 5). In contrast, there was abundant Iba1 staining within and outside the tumor of the Amp B–treated group, which was significantly higher compared with vehicle controls (P<.05, Student’s t-test). For paraffin sections, although it is difficult to resolve that the iron is colocalized with the Iba1-positive cells, iron staining was visible in tumor areas that also have abundant amounts of Iba1 staining (Fig. 6). We included a negative control for the iron staining, in which we skipped the iron localization step (incubation in HCl and potassium ferrocyanide). The negative control had no brown staining on the slide (not shown).

Fig. 5.

(A–D) Immunohistochemistry shows that there is significantly more Iba1 staining in the Amp B animals (B and D) compared with vehicle-treated controls (A and C). (E) Quantification of Iba1 staining showed that there are significantly more Iba1-positive cells (normalized to tumor area) in the Amp B–treated animals compared with vehicle. Scale bars represent 100 μm. *P<.05, Student’s t-test.

Fig. 6.

Histological staining in Amp B tumor for (A, C) macrophage/microglia (Iba1), and (B, D) DAB-enhanced Perl’s (iron) staining on the adjacent paraffin slide. This shows that there are macrophages and microglia (brown cells) and that there is iron accumulation in the tumor (small brown spots). Scale = 100 μm. MRI data for this animal is shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

While the incubation of cells with iron followed by their injection into animals has been used to track these labeled cells, the intravenous injection of USPIO has also been employed to label monocytes in other animal studies. Specifically, USPIO-MRI has been used in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis with significant inflammatory responses. It was shown that there was a decrease in signal on T2* weighted MRI in EAE, which was reduced after treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug lovastatin,19 suggesting that USPIO uptake and MRI can be used to detect the activity of immune cell trafficking. Previous work, using fluorescently tagged USPIO , also found that there was significant T2* darkening post-injection with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a strong immune stimulant, which was completely ablated when circulating monocytes were depleted using clodronate liposomes before treatment with LPS.20 The authors then confirmed that the fluorescent USPIO was colocalized with F4/80-stained macrophages. This provided strong evidence that signal changes observed on T2* scans were predominantly caused by circulating monocytes that carried iron into the brain.

Our results of T2* and histology show that Amp B enhanced the transfer of iron into the brain tumor. The most likely cause was that monocyte phagocytosed the iron in the circulation and carried it into the tumor, as Amp B is known to increase monocyte activation and infiltration into intracranial GBM in mice.2

Aside from being carried over by monocytes, the trafficking of USPIO could also come from a nonspecific movement of iron across the BBB. Ferumoxytol did not appear to leak into the tumor in the vehicle-treated animals, evident from the fact that there was no significant change in T2* postcontrast. Moreover, examining normal appearing brain parenchyma, we found no significant changes in T2* in the Amp B–treated animals, suggesting that Amp B did not cause a global increase in BBB permeability. Nonetheless, to rule out the possibility that Amp B caused a selective disruption of tumor BBB, we used Gd-enhanced MRI to assess the status of the BBB. We showed that the BBB disruption was localized to the tumor, and Gd enhancement was similar in both Amp B– and vehicle-treated animals.

The phenomenon of brain tumors being permeable to Gd but not ferumoxytol has been reported in clinical studies measuring cerebral blood volume to evaluate pseudoprogression. It was shown that ferumoxytol does not leak into a Gd-permeable BBB and is a better blood pool agent to quantify cerebral blood volume.24,25 This can be attributed to their size difference, as Gd is a much smaller molecule than ferumoxytol (950Da vs 750kDa, respectively). However, this raises the possibility that Amp B treatment might be causing a disruption in the upper ranges of the BBB, allowing ferumoxytol to leak into the tumor.

To address this possibility, we used 500kDa FITC-dextran molecules to investigate the BBB of Amp B–treated animals. We found that blood vessels within the tumor of Amp B–treated animals appeared similar to the ones found in normal brain parenchyma with respect to how well the blood vessels were defined. This suggests that there is very little FITC leaking into the tumor.

Although there is evidence indicating that ferumoxytol does not leak across a tumor BBB acutely, it is still possible for ferumoxytol to cross the BBB via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects.26 We allowed the FITC to circulate for 1h, with the goal of giving time for unregulated diffusion across a broken BBB. This study paradigm could not discount the possibility of ferumoxytol entering the tumor via EPR over much longer time periods. It is possible that some of the contrast enhancement we observed is due to ferumoxytol entering the tumor via EPR. However, due to its short half-life, it was not possible to let FITC circulate longer to account for EPR effects.

Thus, we moved on to verify our hypothesis by histopathology. If changes in T2* were indeed related to monocyte phagocytosing ferumoxytol and subsequently migrating into the tumor, we should see an increase in the number of Iba1-positive cells in the tumor of Amp B‒treated animals. In addition, we should see colocalization of Iba1 with iron staining.

Indeed, quantification of the number of Iba1-positive cells in the tumor showed an elevated number of Iba1 cells in the Amp B–treated animals compared with vehicle animals. The change is important to note, as Iba1 stains both resident microglia as well as infiltrated monocytes (macrophages). The increase in Iba1-positive cells in our study appeared less than previously reported.2 This may be caused by the duration of treatment. We treated the current animals for only 7 days with Amp B, while the previous results were obtained after 40 days of Amp B treatment. The short treatment time used in our study likely accounts for why there was no significant difference in tumor volume between vehicle and Amp B animals.

Examining the iron and the Iba1 staining, it is difficult to claim that the 2 stains were colocalized in adjacent paraffin sections. However, iron signals were located around areas with high levels of Iba1 staining, suggesting that USPIOs are engulfed by phagocytic cells. This supports our hypothesis that ferumoxytol was engulfed by monocytes in the blood and carried across into the tumor tissue, suggesting that changes in T2* were detecting the migration of monocytes.

We provided evidence that the Amp B–induced increase in monocyte infiltration into the tumor can be detected with ferumoxytol using T2* mapping. However, it must be pointed out that the objective of our manuscript is to show proof of principle, so it does not address whether this Amp B–related treatment phenomenon is associated with future tumor shrinkage. Our work is the first step to potentially demonstrate that ferumoxytol can be used to detect the efficacy of innate immune stimulating therapies, but more work is needed to fully establish the relationship between T2*, monocyte infiltration, and tumor control.

In conclusion, we showed that USPIO-MRI can be used as a rapid method to detect pharmacologically induced increases in monocyte infiltration into brain tumors. We observed a treatment-associated phenomenon with as little as 7 days of treatment; this method should be applicable to any drug that affects innate immunity. We showed that the effects of immune stimulating drugs can be detected in the context of GBM. This is a promising technique, and further work is needed to consolidate the relationship between USPIO-MRI findings and prognosis.

Funding

This study was funded by Alberta Innovates Health Solutions - Alberta Cancer Foundation Collaborative Research and Innovation Opportunities grant (R.Y., S.S., Y.W. J.F.D., V.W.Y.) and Branch Out Neurological Foundation Graduate Studentship (R.Y.).

Conflict of interest statement. None

References

- 1. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sarkar S, Doring A, Zemp FJ, et al. Therapeutic activation of macrophages and microglia to suppress brain tumor-initiating cells. Nat Neurosci. 2014; 17(1):46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gustafson MP, Lin Y, New KC, et al. Systemic immune suppression in glioblastoma: the interplay between CD14+HLA-DRlo/neg monocytes, tumor factors, and dexamethasone. Neuro Oncology. 2010; 12(7):631–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jackson C, Ruzevick J, Phallen J, et al. Challenges in immunotherapy presented by the glioblastoma multiforme microenvironment. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011; 2011:732413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wurdinger T, Deumelandt K, van der Vliet HJ, et al. Mechanisms of intimate and long-distance cross-talk between glioma and myeloid cells: how to break a vicious cycle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014; 1846(2):560–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manthey CL, Johnson DL, Illig CR, et al. JNJ-28312141, a novel orally active colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor/FMS-related receptor tyrosine kinase-3 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potential utility in solid tumors, bone metastases, and acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009; 8(11):3151–3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pyonteck SM, Akkari L, Schuhmacher AJ, et al. CSF-1R inhibition alters macrophage polarization and blocks glioma progression. Nat Med. 2013; 19(10):1264–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korchinski DJ, Taha M, Yang R, et al. Iron oxide as an MRI contrast agent for cell tracking. Magn Reson Insights. 2015; 8(Suppl 1):15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berry CC, Wells S, Charles S, et al. Dextran and albumin derivatised iron oxide nanoparticles: influence on fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2003; 24(25):4551–4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Namkung S, Zech CJ, Helmberger T, et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced liver MRI with ferucarbotran: efficacy for characterization of focal liver lesions. J Magn Reson Imaging: JMRI. 2007; 25(4):755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takahama K, Amano Y, Hayashi H, et al. Detection and characterization of focal liver lesions using superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison between ferumoxides-enhanced T1-weighted imaging and delayed-phase gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2003; 28(4):525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hetzel D, Strauss W, Bernard K, et al. A phase III, randomized, open-label trial of ferumoxytol compared with iron sucrose for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with a history of unsatisfactory oral iron therapy. Am J Hematol. 2014; 89(6):646–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spinowitz BS, Kausz AT, Baptista J, et al. Ferumoxytol for treating iron deficiency anemia in CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2008; 19(8):1599–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crimi A, Commowick O, Maarouf A, et al. Predictive value of imaging markers at multiple sclerosis disease onset based on gadolinium- and USPIO-enhanced MRI and machine learning. PloS one. 2014; 9(4):e93024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vellinga MM, Vrenken H, Hulst HE, et al. Use of ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide (USPIO)-enhanced MRI to demonstrate diffuse inflammation in the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients: an exploratory study. J Magn Reson Imaging: JMRI. 2009; 29(4):774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kleinschnitz C, Bendszus M, Frank M, et al. In vivo monitoring of macrophage infiltration in experimental ischemic brain lesions by magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2003; 23(11):1356–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly JJ, Stechishin O, Chojnacki A, et al. Proliferation of human glioblastoma stem cells occurs independently of exogenous mitogens. Stem cells. 2009; 27(8):1722–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang FW, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, et al. A mouse model of juvenile hemochromatosis. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115(8):2187–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Floris S, Blezer EL, Schreibelt G, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability and monocyte infiltration in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: a quantitative MRI study. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2004; 127(Pt 3):616–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mori Y, Chen T, Fujisawa T, et al. From cartoon to real time MRI: in vivo monitoring of phagocyte migration in mouse brain. Scientific reports. 2014; 4:6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larochelle C, Alvarez JI, Prat A. How do immune cells overcome the blood-brain barrier in multiple sclerosis? FEBS Lett. 2011; 585(23):3770–3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mennicken F, Maki R, de Souza EB, et al. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in the CNS: a possible role in neuroinflammation and patterning. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999; 20(2):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agrawal S, Anderson P, Durbeej M, et al. Dystroglycan is selectively cleaved at the parenchymal basement membrane at sites of leukocyte extravasation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006; 203(4):1007–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gahramanov S, Muldoon LL, Varallyay CG, et al. Pseudoprogression of glioblastoma after chemo- and radiation therapy: diagnosis by using dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging with ferumoxytol versus gadoteridol and correlation with survival. Radiology. 2013; 266(3):842–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nasseri M, Gahramanov S, Netto JP, et al. Evaluation of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma multiforme using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging with ferumoxytol calls RANO criteria into question. Neuro Oncology. 2014; 16(8):1146–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. England CG, Im HJ, Feng L, et al. Re-assessing the enhanced permeability and retention effect in peripheral arterial disease using radiolabeled long circulating nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2016; 100:101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]