Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and lethal type of primary tumor in the central nervous system. The median survival is literally less than 15 months.1 However, the prognosis can be highly variable in the clinical situation. In addition to traditional prognostic factors, the importance of molecular signatures, such as mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and promoter methylation of O6-DNA methylguanine-methyltransferase (MGMT), has drawn increasing attention in GBM management.2,3 Consequently, the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification system has incorporated IDH mutation into the classification of GBM.4 Despite knowledge of numerous valuable prognostic factors, there is still an urgent need to combine them for a comprehensive and individualized prediction.

Nomograms are graphical depictions of predictive statistical models, which have a demonstrated advantage over traditional systems in individualized prediction and have been developed for various types of cancers.5 Recently, Haley Gittleman et al reported on the presentation of a nomogram for predicting overall survival in newly diagnosed GBM.6 We commend the authors for performing the largest study to date on the development and validation. However, we noted that patients in both training and validation sets were derived from 2 American clinical trials, and were predominantly white. Additionally, their treatment strategy was based on standard combined treatment,7 while in clinical practice not all patients undergo Stupp’s regimen, suggesting that it is necessary to consider different treatment strategies for comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, Gittleman’s study was absent of information on IDH mutation, which is a key factor for GBM classification and prognostic prediction. The above points raise our concerns on interpreting these results in the broad clinical setting. Therefore, we aimed to validate their nomogram in an Asian cohort and investigate whether considering different treatment conditions and IDH mutational status could improve the validity of the nomogram.

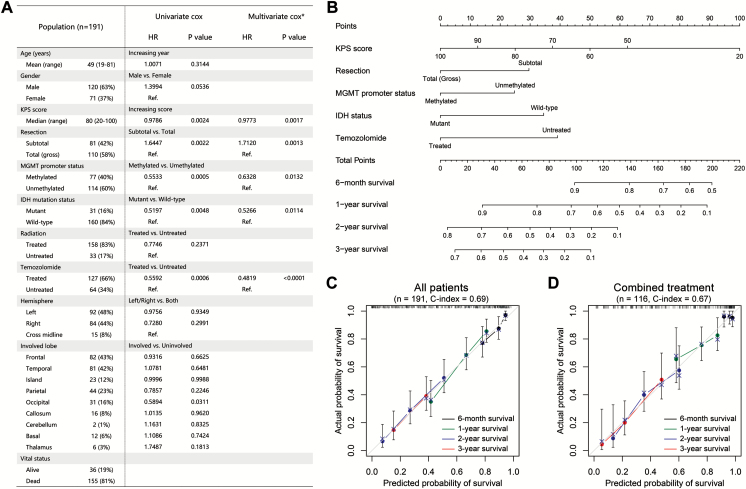

Here, we retrospectively reviewed 191 primary GBMs from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) cohort to validate Gittleman’s nomogram and develop a new nomogram for Chinese patients. There were 155 events (deaths) over a median follow-up time of 14.8 months (range, 33 d to 8.4 y). The clinicopathologic characteristics of patients are listed in Fig. 1A. Univariate Cox regression indicated that higher KPS score, total resection, methylated MGMT promoter, IDH mutation, temozolomide treatment, and occipital involvement were associated with a better prognosis (Fig. 1A). Multivariate Cox regression (backward stepwise) continued to demonstrate that KPS score, resection, MGMT promoter status, IDH mutational status, and temozolomide treatment remained independent risk factors for primary GBM (Fig. 1A). These factors were further tested using the Akaike information criterion,8 thus giving confidence to the robustness of our results.

Fig. 1.

(A) The summary of clinicopathologic features and results of Cox regression analyses in our analysis. *, backward stepwise Cox regression analysis. (B) Prognostic nomogram for patients with GBM. (C and D) The calibration curves for predicting patient survival at each time point in the primary cohort (C) and combined treatment cohort (D).

A nomogram incorporating the independent prognostic factors was established (Fig. 1B). The nomogram illustrated that KPS score was the largest contributor to prognosis, followed by temozolomide treatment, IDH mutation status, resection, and MGMT promoter status. We calculated the concordance index (C-index) to evaluate the performance of our nomogram. The C-index of our nomogram was 0.69, which was significantly higher than that obtained by applying Gittleman’s nomogram in this cohort (C-index = 0.61, P = .0004) and the constituting factors (KPS, C-index = 0.59, P < .0001; resection, C-index = 0.56, P < .0001; MGMT promoter status, C-index = 0.56, P < .0001; IDH status, C-index = 0.55, P < .0001; temozolomide treatment, C-index = 0.60, P < .0001). A calibration plot for the probability of survival at 6 months and 1, 2, and 3 years showed an optimal agreement between actual observation and the prediction (Fig. 1C).

Subsequently, we applied our nomogram for patients who received standard combined treatment.In the combined treatment cohort, the C-index was greater for our nomogram (C-index = 0.67) than for Gittleman’s nomogram (C-index = 0.63), although the difference was not statistically significant. The calibration plot presented a good agreement between the prediction based on our nomogram and actual observation for 6-month and 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival (Fig. 1D), verifying the validity of our nomogram for patients who received combined treatment.

In the present study, we tested the effectiveness of Gittleman’s nomogram in a Chinese cohort and obtained similar results as their report. We developed a nomogram incorporating IDH status and treatment strategy with greater validity for Chinese patients. We found that considering differences in treatment condition could expand the application range of a nomogram without impairing its validity. Moreover, IDH mutation consistently conferred better prognosis in our analysis, highlighting its necessity in inclusion for improving the nomogram. Therefore, our study may provide some implications for developing an optimal nomogram in primary GBM.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 81172409, 81472360, and 81402045) and the Science and Technology Department of Liaoning Province (grant number: 2011225034) and the National Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2016YFC0902500).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have applied for a patent concerning this work.

References

- 1. Jiang T, Mao Y, Ma W, et al. ; Chinese Glioma Cooperative Group (CGCG). CGCG clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult diffuse gliomas. Cancer Lett. 2016;375(2):263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):e173–e180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gittleman H, Lim D, Kattan MW, et al. An independently validated nomogram for individualized estimation of survival among patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: NRG Oncology RTOG 0525 and 0825. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(5):669–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15(4):361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]