Abstract

Background.

As the incidence of pseudo-progressive disease (psPD), or pseudoprogression, in low-grade glioma (LGG) is unknown, we retrospectively investigated this phenomenon in a cohort of LGG patients given radiotherapy (RT).

Methods.

All MRI scans and clinical data from patients with histologically proven LGG treated with radiation between 2000 and 2011 were reviewed. PsPD was scored when a new enhancing lesion occurred after RT and subsequently disappeared or remained stable for at least a year without therapy, including dexamethasone.

Results.

Sixty-three out of 71 patients who received RT for LGG were deemed eligible for evaluation of psPD. The median follow-up was 5 years (range 1‒10 y). PsPD was seen in 13 patients (20.6%). PsPD occurred after a median of 12 months with a range of 3–78 months. The median duration of psPD was 6 months, with a range of 2–26 months and always occurred within the RT high dose fields of at least 45 Gy. The area of the enhancement at the time of psPD was significantly smaller compared with the area of enhancement during “true” progression (median size 54mm2 [range 12–340mm2] vs 270mm2 [range 30–3420mm2], respectively; P = .009).

Conclusions.

PsPD occurs frequently in LGG patients receiving RT. This supports the policy to postpone a new line of treatment until progression is evident, especially when patients have small contrast enhancing lesions within the RT field.

Keywords: glioma, LGG, low-grade glioma, pseudoprogression, radiotherapy.

Importance of the Study

The phenomenon of progressive enhancing MRI lesions in high-grade gliomas (HGGs) after chemoradiation with spontaneous improvement was termed pseudoprogression (psPD). PsPD and its incidence in HGG are now firmly established. As little is known about (the incidence of) psP in LGG, we investigated this in a cohort of 71 LGG patients receiving a relatively low dose of RT (median 50.4 Gy) and found a remarkably high incidence of psPD in 20.6% of these patients. The area of the enhancement at the time of psPD was significantly smaller compared with the area of enhancement during “true” progression and notably almost 50% of the psPD enhancing lesions were located subependymally in the ventricular wall. We therefore propose not to change the therapeutic strategy in LGG patients after RT in case of an asymptomatic small (bidirectional diameter <10 mm) enhancing lesion within the RT field, especially when this lesion is located subependymally.

Low-grade gliomas (LGGs; World Health Organization [WHO] grade II) affect predominantly young adults and have a relatively favorable prognosis compared with high-grade gliomas (HGGs; WHO grade III and grade IV). LGGs include astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and oligoastrocytomas. The median survival time ranges from 5 years up to 13–15 years for oligodendrogliomas with 1p/19q codeletion.1,2 Molecular markers such as 1p/19q chromosomal codeletion and isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations have been correlated with better treatment response and survival.3

Until recently, the standard of care in patients with a high-risk LGG was optimal resection followed by external beam radiotherapy (RT).1 Recent mature data of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9802 trial have shown an increase of the median overall survival (OS) to 13.3 years in patients who received RT followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with procarbazine/lomustine/vincristine (PCV), compared with 7.8 years in patients who received RT only.4 Therefore, RT with adjuvant PCV has now become the standard of care in high-risk LGG patients.

In oncology, therapeutic efficacy in general is evaluated by assessing the response to therapy with imaging and OS. In LGG, specifically, the evaluation of tumor status is more complicated. A number of pitfalls can interfere with proper response assessment. Most LGGs do not enhance on MRI scans after gadolinium and appear as an area of increased T2 or fluid attenuated inversion recovery signal on the MRI scan, often with mass effect. The recurrence after primary treatment is often heralded with an enhancing lesion on MRI, evidence of a malignant transformation of tumor into an HGG. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria for LGG accept an increase in enhancement as evidence of malignant transformation, but changes in enhancement after RT do not necessarily equal changes in tumor size.1 Enhancement also occurs when the blood–brain barrier is disrupted by abnormal vessel permeability—for example, in inflammation, infection, postsurgical scarring, or early radiation-induced changes. Also seizures can cause quite large areas of enhancement.5 Nonetheless, as a rule new areas of enhancement in a previously non-enhancing tumor are routinely understood as evidence of tumor progression.

Recently, there has been an increased interest in RT-induced MRI changes. Studies have made clear that with classical MRI using T1- (before and after gadolinium) and T2-weighted images, it is impossible to distinguish early RT-induced reactive changes (also known as pseudoprogression) from tumor progression.6 Radiation-induced changes may occur earlier and more frequently (in 20% of patients) when RT is combined with temozolomide chemotherapy.7–9 RT with or without chemotherapy may alter the capillary permeability and disrupt the blood–brain barrier, which results in enhancement that is indistinguishable from tumor progression.8,10,11 This phenomenon of progressive, radiation-induced, enhancing MRI lesions in HGGs, with spontaneous improvement without further treatment, was termed pseudo-progressive disease (psPD), or pseudoprogression. The incidence of psPD in LGG after RT is, however, largely unknown. We therefore evaluated the incidence of psPD in a cohort of LGG patients treated with RT.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective cohort study we reviewed all patients with histologically proven LGG who received external beam RT between January 2000 and December 2011 in the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands. This retrospective study was conducted according to local and national regulations and was approved by the institutional review board.

RT was mostly 3D conformal, given to the remaining tumor and resection cavity with 1–2cm margins around areas of T2 signaling abnormalities. Details about the treatment (previous and follow-up treatments, RT dose, treatments after the RT), clinical condition, medication (especially dexamethasone), progression-free survival (PFS), and survival were collected from the patient files. Per institutional guidelines, MR imaging was performed before and after operation, before and after RT, and every 6 months thereafter, but MR imaging was done at least every 3 months in case of a new enhancing lesion not judged by the treating physician as true progression.

All MRI scans before and after the operation and before and after RT, until progression as judged by the treating physician resulting in the start of a new line of treatment, were reviewed by 2 independent reviewers (S.E.v.W and H.G.d.B). They reviewed the MRI scans for measurement of the T2 and enhancing lesions. In case of discrepancies, a third reviewer (W.T.) also reviewed all scans and the majority vote was followed. The T2- and T1-weighted scans before and after gadolinium were evaluated. PsPD was scored when a new enhancing lesion occurred and this new lesion disappeared or remained stable for at least a year without new therapy or the start of dexamethasone. Tumor progression and response were defined using the RANO criteria.1 As per RANO criteria, progression was defined by any of the following: (1) a 25% increase of the T2 non-enhancing lesion on stable or increasing doses of corticosteroids; (2) development of new lesions or increase of enhancement (suggesting radiological evidence of malignant transformation); or (3) definite clinical deterioration not attributable to other causes apart from the tumor, or decrease in corticosteroid dose. In case of (2) and (3), definite progression was only scored if this led to the start of a new treatment as judged by the treating physician.

OS was calculated from the start of RT to the date of death. PFS was calculated from the start of RT until the date of true progression or death, whichever came first. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to compare OS and PFS and log rank to compare the psPD group with the non-psPD group. To compare differences between means we used the independent-samples median test. Because of the multiple comparisons, P-values of less than .01 were considered to indicate significance. We used SPSS Statistics v21, Excel v14.0.7140.5002, and Access v14.0.7140.5002.

Results

All 71 patients received external beam RT for LGG, with a median total dose of 50.4 Gy, between 2000 and 2011. Sixty-three patients were evaluable for psPD: 3 patients were lost to follow-up and 4 were not evaluable due to missing scans; 1 patient was only evaluated for response because of missing T1-weighted MRI scans after gadolinium, due to a gadolinium allergy. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of those 64 patients. None of the patients had an enhancing MRI lesion at baseline. The median follow-up was 5 years (range 1–10 y). An objective response was seen in 48.4% of the patients (a partial response in 18.8% and a minor response in 32.8%); 26.6% of the patients had stable disease.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 64 patients with LGG given RT

| Baseline Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number | 64 |

| Age, y | |

| Median | 45 |

| Range | 22–73 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 45 (70%) |

| Female | 19 (30%) |

| Histopathology, no of patients | |

| Oligodendroglioma | 17 (27%) |

| Astrocytoma | 29 (45%) |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 16 (25%) |

| Unspecified LGG | 2 (3%) |

| First symptom | |

| Epilepsy vs no epilepsy, % | 92: 8 |

| WHO performance score | |

| 0–1 vs 2, % | 91: 9 |

| Initial surgery | |

| Complete or partial | 38 (59%) |

| Biopsy | 26 (41%) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Before RT | 9 (14%): 5 with TMZ, 4 with PCV |

| After RT | 37 (58%): 26 with TMZ, 6 with PCV, 5 with CCNU |

| Tumor volume pre-RT, mm2 | |

| Median | 2502 |

| Range | 231–15990 |

| Radiation, Gy | |

| Median | 50,4 |

| Range | 50,4–60,0 |

| 1p/19q in patients with OD and OAII | |

| Loss | 13 (OD 8, OAII 5) |

| No loss | 13 (OD 7, OAII 6) |

| Not determined | 7 (OD 2, OAII 5) |

| IDH1 mutation | |

| Yes | 7 |

| Unknown | 57 |

Abbreviations: TMZ: temozolomide; PCV: procarbazine, CCNU and vincristine chemotherapy; CCNU: lomustine; OD: oligodendroglioma; OAII: oligoastrocytoma grade II.

In 13 out of 63 patients (20.6%; 95% CI, 10.4%–30.9%) psPD occurred (Fig. 1–3). Two out of those 13 patients with psPD had a second period with psPD. In the patients with psPD, 4 had an astrocytoma, 4 had an oligodendroglioma, 4 had an oligoastrocytoma, and 1 had an undefined LGG. PsPD occurred after a median of 12 months from the end of the RT (95% CI, 9.7–32.33; range 3–78 mo). The median duration of the psPD was 6 months (95% CI, 5.47–13.07; range 2–26 mo). Of the 2 patients with a second occurrence, one patient had psPD from 5 to 23 months and from 37 to 43 months, and the other patient had psPD from 10 to 36 months and 40 to 56 months after the RT. The second occurrence of psPD was in a different location from the first in both patients. No differences were found between the patients with or without psPD with respect to the baseline characteristics. No significant difference in RT dose between the groups with or without psPD was found (median RT dose 54 Gy vs 50.4 Gy; independent sample t-test, P = .102). Eight of the 13 patients (62%) with psPD had an RT dose above 50.4 Gy versus 18 of the 51 patients (35%) without psPD. There was no significant difference in volume of the planning target volumes (PTV) between patients with or without psPD (median PTV 499 cc vs 371 cc; independent sample t-test, P = .145).

Fig. 1.

MRI scans from 32-year-old male with an astrocytoma in the right frontal-temporal lobe, treated with postoperative radiation (total dose 50.4 Gy). (A) MRI scan 36 months after the RT with no enhancement. (B) MRI scan 42 months after RT, with an enhancing lesion in the ventricle wall of the opposite left hemisphere, but still within the RT field. (C) MRI scan 45 months after RT and 3 months after the appearance of the enhancing lesion shows no enhancement. He received no dexamethasone or other treatments during this period and remained clinically stable. He radiologically progressed 53 months after the RT.

Fig. 3.

MRI scans from 46-year-old male with an oligodendroglioma in the right frontal-temporal lobe, treated with postoperative radiation (total dose 50.4 Gy). (A) MRI scan 22 months after the RT with no enhancement. (B) MRI scan 25 months after RT shows an enhancing lesion in the right temporal lobe, within the RT field. (C) MRI scan 41 months after RT, and 26 months after the appearance of the enhancing lesion it has disappeared. No dexamethasone or further treatments were given and he remained clinically stable. At the time of analysis for this study, 43 months after the RT, he still had no progressive disease.

The median size of the enhancing lesions due to psPD was significantly less than the enhancing lesions at the time of progression (respectively 54mm2, range 9–340mm, vs 270mm2, range 30–3420, independent sample t-test, P = .035). Notably, in 7 of 15 events of psPD (46.7%) the enhancing lesion was located subependymally in the ventricular wall (Figs 1 and 2). All enhancing psPD lesions were clinically asymptomatic and clear surrounding edema was not seen, although subtle edema could have been missed, as most patients had a preexisting high signal on T2-weighted imaging due to residual tumor or radiation-induced white matter changes. Distinction between residual tumor or radiation-induced white matter changes was not always possible, and in theory some of the patients judged as having non-enhancing progression could in fact have had radiation-induced white matter changes. Clear surrounding edema on the T2-weighted MRI scans was seen in 3 out of the 35 patients judged as having real progressive enhancing lesions. Perfusion MRI was available in 5 of the 15 psPD lesions and in 19 of the 35 enhancing progressive lesions. Perfusion was high (relative cerebral blood volume [rCBV] >1.75) in one of the 5 psPD lesions (20%) and 13 of the 19 progressive lesions (68%).12 We do not have histological information on the progressive or psPD lesions, as none of these lesions were biopsied or resected.

Fig. 2.

MRI scans from 53-year-old female with an oligoastrocytoma treated with postoperative radiation (total dose 60 Gy). (A) MRI scan 7 months after the RT with no enhancement. (B) MRI scan 14 months after RT with an enhancing lesion in the left ventricle wall (arrow), within the RT field. (C) MRI scan 21 months after RT and 14 months after the appearance of the enhancing lesion shows no enhancement. The patient remained clinically stable in this period without need for dexamethasone and without further treatments. At the time of analysis for this study, 84 months after the RT, she had no progressive disease.

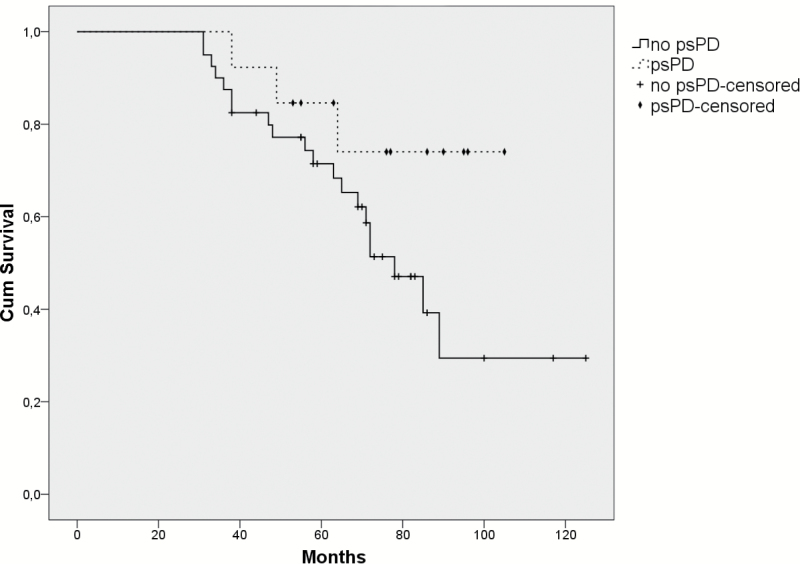

The OS in our cohort of patients with psPD was significantly higher than the OS of the patients without psPD (median OS not reached vs 5.8 y; P = .02; log-rank). Because of a possible time bias, as patients with psPD have to live long enough to meet the definition of psPD, a landmark time was taken at the 95th percentile of the time to development of psPD (30.8 mo). The patients with progression or death before this landmark time were excluded from this analysis. After this correction, the OS between the patients with or without psPD was not significantly different (log-rank, P = .090; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the patients with psPD versus the patients without psPD. Patients without psPD were excluded from this analysis if they died before the 95th percentile of the time to development of psPD (30.8 mo), to avoid a possible time bias, as patients with psPD have to live long enough to meet the definition of psPD. After this correction, the OS between the patients with and without psPD was not significantly different (log-rank, P = .090).

Discussion

The phenomenon and incidence of psPD in HGG after chemoradiation are now firmly established, but little is known about psPD in LGG. In LGG patients, a lower dose of RT is given without concomitant chemotherapy. We found a strikingly high incidence of psPD (20.6%) in this retrospective study in LGG patients treated with a moderate dose of radiation (median 50.4 Gy). Of the 40 patients with new enhancement during follow-up, 13 (29.5%) were found to have psPD. As psPD was per definition only scored in the absence of treatment with dexamethasone, this high incidence of psPD cannot be explained by steroid use. The true incidence of psPD may be even higher, as patients with psPD may have been judged to have real progression by the treating physician and were given second-line treatment. Notably, 3 out of 31 patients in our cohort judged to have true progression had small enhancing lesions (234, 456, and 195mm2), a complete response of the enhancing lesion, and a longer PFS after salvage treatment (20, 32, and 38 mo) compared with the PFS after RT (15, 19, and 22 mo).

Despite many studies on the incidence of psPD in HGG,6,8,9,13,14 to our knowledge only 2 studies investigated the incidence of psPD in LGG after RT. Naftel et al15 found 54.2% of patients with psPD. However, this study included only children, and most of them (70.8%) had juvenile—usually enhancing—pilocytic astrocytomas. Lin et al found a comparable incidence of psPD (19%), but this study also included patients with WHO grade III glioma, receiving a higher dose of RT.16

HGG patients with psPD after chemoradiation have been described as having improved survival, due to favorable correlation with methylated O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter status.9 We did not find a statistically significant increase in survival (P = .09), although this could be due to the small number of patients (see Fig. 4). Our findings are in agreement with those of Lin et al, who also did not find a correlation between psPD and improved survival in WHO grades II and III oligodendroglial tumors.16

One of the shortcomings of this study is that we do not have enough data on the IDH status of the patients, especially given the recent publication of the 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System.17 However, the focus of this study is not on outcome, but on psPD in a group of patients receiving a relatively low dose of RT (median 50.4 Gy). We therefore think that the IDH status is less important in this study. While this is a study with several other shortcomings, such as its retrospective nature, no data on MGMT methylation status, no PET scans, and no histology from the new enhancing lesions, we think that the unexpectedly high incidence of psPD after a relatively low dose of RT is an important finding, warning physicians not to start unnecessary treatment in these patients.

The high incidence of psPD in this study underscores the importance of differentiating patients with psPD from patients with progressive disease (PD), as on one side we would withhold treatment in patients with real PD while, in the case of psPD, we would give patients unnecessary treatment. Regrettably, no significant differences were found between patients with or without psPD, in terms of baseline characteristics, RT dose, or target volumes. The study by Lin et al in patients with WHO grades II and III oligodendrogliomas and mixed oligoastrocytomas found a lower risk of psPD in patients with 1p/19q codeletions.16 In our study, the correlation between psPD and loss of 1p/19q could not be established due to the small number of patients with oligodendroglial tumors in which 1p/19q was determined.

Fortunately, 2 important differences were found between patients with real PD versus psPD. Firstly, the psPD lesions were significantly smaller compared with the PD lesions (median 54mm2 vs 270mm2) and only one patient with psPD had an enhancing lesion with a bidirectional diameter of ≥10mm. Secondly, almost half of the psPD enhancing lesions were located subependymally in the ventricular wall, as compared with one quarter of the real PD enhancing lesions. Others have also found a predilection for periventricular involvement for radiation-induced enhancement. It has been postulated that this may be caused by a relatively poor blood supply in the periventricular area, making this area more vulnerable to radiation-induced ischemic processes.14,18 These findings support the approach to postpone new treatments in asymptomatic LGG patients after RT, until further progression is evident when they have small contrast-enhancing lesions (bidirectional diameter of <10mm) within the RT field, especially when these lesions are located in the ventricle wall.

To our knowledge, more advanced imaging techniques, such as PET, MR spectroscopy, and diffusion-weighted and perfusion imaging, yield no distinction between real PD and psPD in an individual patient, although some techniques appear to be promising.13,19 The number of available perfusion MRIs in our study was not enough to draw any conclusions.

The phenomenon of psPD in HGG is likely related to enhanced inflammation and disruption of the blood–brain barrier caused by radiation itself. Radiation is known to increase the capillary permeability and alter the blood–brain barrier, which causes leakiness of contrast and an increased contrast enhancement in the absence of tumor progression.18 Furthermore, psPD changes in HGG could be caused by inflammatory or necrotic processes.20,21 PsPD in HGG is most commonly described as occurring within 3 months after the RT. The timeframe in which psPD occurs in our cohort of LGG patients is quite different, with a median of 12 months (range 3–78 mo) post RT. Therefore, it is likely that the pathophysiological mechanism of psPD in LGG is different from psPD in HGG. One possible mechanism of psPD in LGG could be asymptomatic small enhancing ischemic infarctions due to radiation-induced microvascular injury. Small enhancing ischemic infarctions could also explain the predilection of the psPD lesions in the periventricular area with poor blood supply, making this area more vulnerable to radiation-induced ischemic processes.14,18 Another mechanism could be small areas of radiation necrosis, which occurs after a median time of 14 months.22 This seems to have a common etiology with “classical” psPD, that is, a complex interaction of a chronic inflammatory process with release of cytokines and reactive oxygen species, and direct damage to glial cells. This leads to endothelial cell damage and disrupted blood–brain barrier, giving rise to vasogenic edema, the release of hypoxia-induced factor 1α, and upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. Eventually this vicious cycle may lead to fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall, ischemia, and demyelination. The radiological signs include contrast enhancement and edema.23 While the pathophysiology of psPD in LGG remains to be clarified, it seems to be part of a spectrum of radiation-related changes ranging from subacute radiographic changes to small ischemic infarctions and late radionecrosis.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after RT is now the standard treatment for high risk LGG patients.4 Markedly, 8 of the 13 patients in this study developed psPD within 48–52 weeks, which equals the timeframe of adjuvant PCV or adjuvant temozolomide. Hence, today adjuvant chemotherapy should be continued in patients developing small enhancing lesions. We propose not to change the therapeutic strategy in LGG patients after RT in case of an asymptomatic small (bidirectional diameter <10mm) enhancing lesion within the RT field, especially when this lesion is located subependymally in the ventricle wall, does not have surrounding edema, and does not show a high rCBV (<1.75).12 Furthermore, the high frequency of psPD in LGG patients after RT also has important consequences for trials involving patients with recurrent LGG. Of the 13 patients with psPD in the current study, all enhancing lesions disappeared without further treatment. If the reported patients in our study with psPD had entered into a phase II trial of recurrent LGG, this would have led to a false-positive study result with a 12-month PFS rate of 92% and a median OS of 50 months. On the other hand, only 1 of the psPD lesions in this study would have fulfilled the RANO criteria for measurable disease, declaring that an enhancing lesion is significant if there is a minimal bidirectional diameter of ≥10mm, visible on at least 2 axial slices, which are preferably 5mm apart. So, when it comes to deciding whether or not to include LGG patients in clinical trials on patients with enhancing progression, the RANO criteria for measurable disease seem adequate.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. van den Bent MJ, Wefel JS, Schiff D, et al. Response assessment in neuro-oncology (a report of the RANO group): assessment of outcome in trials of diffuse low-grade gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumthekar P, Raizer J, Singh S. Low-grade glioma. Cancer Treat Res. 2015;163:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Claus EB, Walsh KM, Wiencke JK, et al. Survival and low-grade glioma: the emergence of genetic information. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38(1):E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buckner JC, Shaw EG, Pugh SL, et al. Radiation plus procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine in low-grade glioma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1344–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rath JJ, Smits M, Ducray F, et al. Increased rCBV in status epilepticus. J Neurol. 2012;259(8):1746–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Wit MC, de Bruin HG, Eijkenboom W, et al. Immediate post-radiotherapy changes in malignant glioma can mimic tumor progression. Neurology. 2004;63(3):535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, et al. Early necrosis following concurrent temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82(1):81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taal W, Brandsma D, de Bruin HG, et al. Incidence of early pseudo-progression in a cohort of malignant glioma patients treated with chemoirradiation with temozolomide. Cancer. 2008;113(2):405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2192–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Wit MCY, de Bruin HG, Eijkenboom W, et al. Immediate post-radiotherapy changes in malignant glioma can mimic tumor progression. Neurology. 2004;63(3):535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dhermain FG, Hau P, Lanfermann H, et al. Advanced MRI and PET imaging for assessment of treatment response in patients with gliomas. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(9):906–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Law M, Young RJ, Babb JS, et al. Gliomas: predicting time to progression or survival with cerebral blood volume measurements at dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;247(2):490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brandsma D, van den Bent MJ. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the treatment of gliomas. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(6):633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, et al. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy–and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology. 2000;217(2):377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naftel RP, Pollack IF, Zuccoli G, et al. Pseudoprogression of low-grade gliomas after radiotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(1):35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin AL, Liu J, Evans J, et al. Codeletions at 1p and 19q predict a lower risk of pseudoprogression in oligodendrogliomas and mixed oligoastrocytomas. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(1):123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, et al. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang RY, Neagu MR, Reardon DA, et al. Pitfalls in the neuroimaging of glioblastoma in the era of antiangiogenic and immuno/targeted therapy—detecting illusive disease, defining response. Front Neurol. 2015;6:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prager AJ, Martinez N, Beal K, et al. Diffusion and perfusion MRI to differentiate treatment-related changes including pseudoprogression from recurrent tumors in high-grade gliomas with histopathologic evidence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(5):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young RJ, Gupta A, Shah AD, et al. MRI perfusion in determining pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(1):41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marks JE, Baglan RJ, Prassad SC, et al. Cerebral radionecrosis: incidence and risk in relation to dose, time, fractionation and volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7(2):243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahmathulla G, Marko NF, Weil RJ. Cerebral radiation necrosis: a review of the pathobiology, diagnosis and management considerations. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(4):485–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]