Abstract

Objective:

To explore salient trends in incidence and mortality from breast cancer among Kuwaiti females and to quantify the number of years that could be saved if breast cancer deaths were eliminated.

Methods:

Appling life table technique, the paper constructs a bridged, multiple decrement and cancer-elimination life tables for Kuwaiti females. Data sources include Kuwait Cancer Control Center Registry along with vital statistics on mortality by age groups, nationality, and causes of death according to ICD-10 revision.

Result:

The study finds that, without interventions, nearly 2.5% of Kuwaiti female live births are expected to die from breast cancer. By contrast, if this disease were to be completely eradicated, Kuwaiti females are expected to gain half a year of life expectancy at birth. Likewise, a 10% reduction in deaths attributed to breast cancer would produce a gain of 11 days of life at age 30. The gain would augment to 51 days when death is reduced by 50%. Kuwaiti females aged 50 would add almost 5 months when breast cancer is eradicated, while a 20 percent reduction in breast cancer mortality would raise their life expectancy by 26 days.

Conclusion:

The results strongly support policy interventions of Kuwait’s government by instituting a well-documented public health policy for chronic diseases and mitigating the increase of cancer prevalence.

Keywords: Breast cancer, elimination life tables, policy intervention

Introduction

Globally, chronic diseases such as ischemic heart diseases and cancer are the leading causes of death due mainly to poor life style choices that are brought on by urbanization and modernization negatively impact people’s life expectancy (GLOBOCAN, 2008). Many countries realize that cancer is a health hazard and the costs associated with fighting it are high and burden the budgets of developing countries (Omar et al., 2007). The World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) declared that cancer caused deaths in the world was 8.2 million in 2012 (WHO, 2015). The newly discovered cases of breast cancer among women in Kuwait represent 38.3% of the newly reported cancer cases in 2012. Kuwait’s percentage was higher than both MENA region (31.1%) and the World (25.1%) during the same year. Women in Kuwait reported higher ASR (W) incidence rate of breast cancer (46.7/100,000) compared to both MENA and World rates at 43.1/100,000 in 2012. In the same year, 26.7% of women cancer deaths are caused by breast cancer. This percentage is higher than what is found in MENA’s (20.9%) and the World (14.7%). Also, mortality ASR (W) of breast cancer among women in Kuwait was 17.3/100,000 in 2012, this rate was higher than the MENA rate (16.2/100,000) and internationally (12.9/100,000) (GLOBOCAN, 2016).

Recent Kuwait statistics confirm that both ischemic heart diseases and cancer are the leading causes of death (Kuwait Health, 2010). Most of cancer deaths in Eastern Mediterranean Region are attributed to two types of cancers: lung and breast (Omar and Khatib, 2007). Meantime, the latest published report by Kuwait Cancer Registry (KCR) concluded that malignant neoplasms of breast (C50) constituted 36.4 percent of the new reported cases among females whereas colon (C18) forms 13.1 percent of the newly reported cases among males in Kuwait (Kuwait Cancer Registry, 2012). Cancer death rate among Kuwaiti females averaged 40 per 100,000 in the past ten years, slightly outscoring the averages of the overall population (38 per 100,000). Mortality from cancer is rising noticeably from approximately 13.4 percent of Kuwaiti female deaths in 1994 to 20.3 percent, while males’ percentage was lower, approximately 11.7 percent and increased to 12.8 percent during the same respective years.

Newly reported C50 cases in Kuwait represent the largest share, 312 cases, or 22 percent of all newly reported malignancies (El Basmi et al., 2007). Kuwaiti females’ share of these new cases was 55 percent (168 cases) reinforcing the contention that breast cancer is spreading rapidly in the country (Al shaibani et al., 2006). Furthermore, the types of breast malignant neoplasms diagnosed in Kuwait are among the most aggressive and dangerous types compared to what is evidenced in other parts of the world (Saleh and Abdeen, 2007; Motawy et al., 2004).

To our knowledge, this paper is the first attempt to address the evaluation and mortality attribution and mitigation of breast cancer among Kuwaiti women. Specifically, our research attempts to quantify the number of years that could be saved if breast cancer deaths were eliminated among Kuwaiti females. In the process, the research provides an assessment of salient trends in incidence of and mortality from breast cancer. The study focuses on Kuwaiti females who are homogeneous and reside permanently in Kuwait as opposed to non-Kuwaiti females who originate from many countries and ethnic groups. Following this introduction, the organization of the remainder of paper as follows: section I reviews the methodology and data used. Section II displays salient results. Section III is a discussion of the study implications. It also discusses the policy significance and caveats of the approvals of findings.

Materials and Methods

Developments in incidence and mortality from breast cancer are analyzed using incidence rates, age-specific death rate, and age-standardized rate in order to show and track the emerging pattern of the disease among Kuwaiti females since 1994. We follow a large body of the literature that utilizes the life table technique as a fundamental technique in mortality analysis and evaluation of the impact of certain diseases on human life. In essence, life table manifests the life span of individuals in the hypothetical cohort on the basis of the actual death rates and survivorship of a given population. Life table techniques can be extended to include the impact of cause of death as well which provides a fictitious picture reflecting the mortality experience of a real population during a given time.

For space considerations, we strictly present the basic abridged life table for Kuwait females representing the average of age-specific mortality rate for the years between 2005 and 2010. Following that, we generate a multiple decrement table for the purpose of assessing the effects of mortality from breast cancer on Kuwaiti females. In the last step, breast cancer-elimination life tables are developed in order to estimate the impact of total and/or partial elimination of the disease on life expectancies of Kuwaiti females at selected age groups. The technique quantifies the number of years added to life expectancy at birth under different scenarios of cancer elimination. Details on the methodologies of life tables can be found in the Appendix (194.6KB, pdf) (Siegel and Swanson, 2004). All life tables were generated using programed cells of Microsoft XL sheets. It should be noted that this methodology is applied for the first time using data from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Arab region, and that is what makes it unique and seminal.

Two sources of data are utilized in the empirical analyses below. The first is KCR data which are produced annually by virtue of the fact that the institute is Kuwait’s official cancer database (KCCC, 2000-2008). The second is vital statistics on mortality classified by age groups, nationality, and causes of death according to WHO ICD-10 revision which are gleaned from the Health Information and Medical Records of Ministry of Health (MOH) (Kuwait Health, 2000-2012). Only malignant neoplasms of breast coded C50 is considered. This item includes: nipple and areola, central portion of breast, upper-inner quadrant of breast, lower-inner quadrant of breast, upper-outer quadrant of breast, lower-outer quadrant of breast, axillary tail of breast and breast unspecified.

Time wise, the study covers the period 1994 to 2012. As of 2016, the issue of 2012 is the latest produced annual report of KCR. While assessment of the data quality is beyond the scope of this paper; we note that GLOBOCAN in year 2012 indicated that the data in incidence provided by KCR is high in quality (GLOBOCAN, 2012). We also refer to the work of Elbasmi et al. (2004) who conclude that the accuracy of the registry data is comparable to that found in other cancer registries after comparing clinical records with KCR. Finally, we emphasize that the data utilized to conduct this study herein are raw tabulated data provided by the KCR. The KCCC is a tertiary referral hospital and is the only cancer hospital in Kuwait. The majority of referred cases are diagnosed in the six general hospitals in Kuwait (Ameen et al., 2010).

Results

Mortality from Cancer

Analysis of time series data on cancer mortality reveals that the annual death rate from cancer fluctuated between 32.1 and 48.1 per 100,000 during 2000 to 2012. The average rate of the period was 38.9 per 100,000, and breast cancer is the leading cause of death among Kuwaiti females compared to other type of cancers.

More noteworthy, the death rate from breast cancer increased between 2000 and 2012 from 7.2 per 100,000 to 11.0 per 100,000. The average death rate from breast cancer during studied time interval was 9.6 per 100,000. Meantime, cancer deaths averaged 16.7 percent of total mortality in Kuwait during the period (Table 1). Remarkably, deaths caused by breast cancer constitute, on average, about 4.1 percent of all reported Kuwaiti female deaths.

Table 1.

Cancer and Breast Cancer Death Rate Per (100000) and Their Share in Total Mortality, Kuwait Females, 2000-2012

| Cancer | Breast Cancer | Total | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Death rate | Death rate | C % | C50 % |

| 2000 | 37.5 | 7.2 | 14.7 | 2.8 |

| 2001 | 40.8 | 11.1 | 17.6 | 4.8 |

| 2002 | 35 | 7.8 | 15.9 | 3.5 |

| 2003 | 35.3 | 7.5 | 17 | 3.6 |

| 2004 | 32.1 | 8 | 15.4 | 3.8 |

| 2005 | 35.1 | 10.1 | 17.3 | 5 |

| 2006 | 37.1 | 7.6 | 15.6 | 3.2 |

| 2007 | 41.3 | 10.4 | 15.3 | 3.9 |

| 2008 | 44.9 | 13.3 | 16.1 | 4.8 |

| 2009 | 41.6 | 10 | 15.8 | 3.8 |

| 2010 | 38.3 | 10.4 | 17.6 | 4.8 |

| 2011 | 38.4 | 10.3 | 18.7 | 5 |

| 2012 | 48.3 | 11 | 20.3 | 4.6 |

| Average | 38.9 | 9.6 | 16.7 | 4.1 |

KCCC, Kuwait Cancer Registry for years 2000-2012; Kuwait Health for years from 2000 and 2012

Incidence of Breast Cancer

Underscoring their critical health policy significance, the number of newly discovered breast cancer cases increased by 7 folds among Kuwaiti females since 1970. The newly reported cases averaged 120 annually during the seventies but escalated to 477 during the nineties, and jumped up further to 1,569 cases annually between 2000 and 2012. Recent trend in newly reported cases of breast cancer among Kuwaiti females and its share of the total newly reported cases of cancer is illustrated in Figure 1. The annual number of discovered cases increased appreciably from 56 cases in 1994 to 212 cases in 2012. As well, the share of the reported breast cancer among all newly reported cancer cases increased commensurately. The share of breast cancer in the number of total newly cancer cases increased from 27.7% in 1994 to almost 35.8% in 2012. However, a declining trend in the percentage started since 2009.

Figure 1.

Trend in New C50 and Their Percentage of Total New Reported Cancer Cases

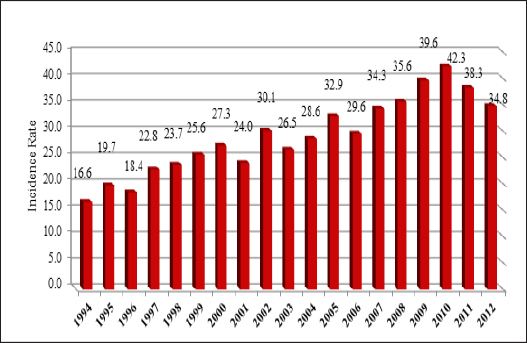

Furthermore, the incidence rate of breast cancer in Kuwait also reveal rising trend since 1994. Breast cancer incidence rate among Kuwaiti females increased from 16.6 per 100,000 in 1994 to 27.3 per 100,000 in 2000 and grew steadily to reach its highest level of 34.8 per 100,000 in 2012 (Figure 2). Worth-noting, the incidence rate of breast cancer was the highest compared to other neoplasms.

Figure 2.

C50 Incidence Rate (100,000)

Mortality from Breast Cancer

Mortality attributed to breast cancer in the total neoplasms deaths among Kuwaiti females averaged 24.6 percent for the period between 2000 and 2012. The share did vary noticeably over time; and remains high as portrayed in Figure 3. Breast cancer deaths accounted for 19.1 percent of all neoplasms mortality in 2000. This share increased noticeably in 2005 when it reached almost 28.7 percent; however decreased substantially to 22.8 percent in 2012.

Figure 3.

Percentage of C50 Deaths From Total Cancer Deaths

A close review of cause-specific death rate for cancer in general and breast cancer in particular reveals that the average breast cancer death rate among Kuwaiti females was 9 per 100,000 during the period 2000-2012, compared to an average death rate of 38 per 100,000 that was caused by cancer in general. Unfortunately, the death rate from breast cancer has been and continues to increase with time. For instance, breast cancer death rate was 7.2 per 100,000 in 2000, only to increase to 10 per 100,000 in 2005, and hovered around that level since then.

The average age-specific death rate (ASDR), for years 2005-2012 from breast cancer seems to be low compared to international levels. However, this low rate is deceiving if taken for face value. More concretely, when controlling for the young age structure of Kuwaiti females and using the age standardization rate (ASR) the result readings change appreciably. To illustrates ASDR for the age group 35 to 39 increased from 8.4 per 100,000 compared to ASR of 47.2 per 100,000, whereas ASDR for the age group 50 to 54 jumped from 35.1 per 100,000 compared to ASR of 133 per 100,000, and finally ASDR compared to ASR for the age group 70 to 74 reveal substantial difference (106 per 100,000 versus 250 per 100,000 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Age-Specific Death Rate and Age-Standardized Rate (W) Of C50

Life Gains

Measuring the impact on life gains of Kuwaiti females which results from mortality reduction of breast cancer deaths enables us to quantify the probable number of years which could be saved. We constructed an abridged life table for Kuwaiti females using the average rates of age-specific mortality rate for the years between 2005 and 2010, Table 2. Note that Kuwaiti females’ life expectancy at birth is currently around 78.9 years, which compares well with women’s life expectancy in western countries.

Table 2.

Abridged Life Table Kuwaiti Females, 2005-2010

| Age | qx | dx | lx | px | Lx | Tx | ex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00854 | 854 | 100,000 | 0.99146 | 99,573 | 7,893,064 | 78.93 |

| 1 | 0.00182 | 181 | 99,146 | 0.99818 | 396,223 | 7,793,491 | 78.61 |

| 5 | 0.00114 | 113 | 98,965 | 0.99886 | 494,544 | 7,397,269 | 74.75 |

| 10 | 0.00117 | 116 | 98,852 | 0.99883 | 493,973 | 6,902,724 | 69.83 |

| 15 | 0.00144 | 142 | 98,737 | 0.99856 | 493,328 | 6,408,751 | 64.91 |

| 20 | 0.00153 | 150 | 98,594 | 0.99847 | 492,596 | 5,915,423 | 60 |

| 25 | 0.00205 | 202 | 98,444 | 0.99795 | 491,715 | 5,422,828 | 55.09 |

| 30 | 0.00215 | 211 | 98,242 | 0.99785 | 490,684 | 4,931,112 | 50.19 |

| 35 | 0.00326 | 320 | 98,031 | 0.99674 | 489,358 | 4,440,429 | 45.3 |

| 40 | 0.00499 | 488 | 97,712 | 0.99501 | 487,339 | 3,951,071 | 40.44 |

| 45 | 0.00878 | 854 | 97,224 | 0.99122 | 483,985 | 3,463,732 | 35.63 |

| 50 | 0.0143 | 1,378 | 96,370 | 0.9857 | 478,406 | 2,979,746 | 30.92 |

| 55 | 0.02532 | 2,405 | 94,992 | 0.97468 | 468,949 | 2,501,340 | 26.33 |

| 60 | 0.05094 | 4,717 | 92,587 | 0.94906 | 451,146 | 2032391 | 21.95 |

| 65 | 0.09097 | 7,994 | 87,871 | 0.90903 | 419,370 | 1,581,245 | 18 |

| 70 | 0.15882 | 12,686 | 79,877 | 0.84118 | 367,671 | 1,161,875 | 14.55 |

| 75 | 0.23558 | 15,829 | 67,191 | 0.76442 | 296,384 | 794,203.9 | 11.82 |

| 80 | 0.33611 | 17,263 | 51,362 | 0.66389 | 213,653 | 497,819.8 | 9.69 |

| 85 + | 1 | 34,099 | 34,099 | 0 | 284,166 | 284,166.3 | 8.33 |

We also conducted counterfactual scenarios that assume that deaths caused by breast cancer is completely eradicated, table 3. The results reflect the possibility of the elimination of death caused by the diseases, rather than the elimination of the disease itself. The discerning reader will also notice the detailed outcome of breast cancer elimination life table as a cause of death among Kuwaiti females. The results confirm that the probability of ultimately dying from breast cancer among live birth Kuwaiti females is 2.5%. The percentage of Kuwaiti females who eventually die from breast cancer increases slightly with age until 60 where the percentage starts to drop discernibly.

Table 3.

Abridged Life Tables of Eliminating Breast Cancer as a Cause of Death, Kuwaiti Females 2005-2010

| Age | Proportion Dying | Number of living at beginning of age interval | Number dying during age interval | Stationary Pop. In this age interval | Stationary Pop in this and subsequent age intervals | Aver. No. of years of life remaining at beginning of age interval. | Probability of eventually dying of specified cause | Gain in life expectancy eliminating specified cause | Gain in life expectancy for those who would have died |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qx | lx | dx | Lx | Tx | ex | Ψx | gx | Yx | |

| 0 | 0.00854 | 100,000 | 854 | 99,573 | 7,941,818 | 79.42 | 0.02477 | 0.49 | 19.68 |

| 1 | 0.00182 | 99,146 | 181 | 396,223 | 7,842,246 | 79.1 | 0.02498 | 0.49 | 19.68 |

| 5 | 0.00114 | 98,965 | 113 | 494,544 | 7,446,023 | 75.24 | 0.02503 | 0.49 | 19.68 |

| 10 | 0.00117 | 98,852 | 116 | 493,973 | 6,951,478 | 70.32 | 0.02506 | 0.49 | 19.68 |

| 15 | 0.00143 | 98,737 | 141 | 493,332 | 6,457,506 | 65.4 | 0.02509 | 0.49 | 19.68 |

| 20 | 0.00153 | 98,596 | 150 | 492,604 | 5,964,174 | 60.49 | 0.02511 | 0.49 | 19.66 |

| 25 | 0.00199 | 98,445 | 196 | 491,738 | 5,471,570 | 55.58 | 0.02515 | 0.49 | 19.66 |

| 30 | 0.00202 | 98,250 | 198 | 490,753 | 4,979,833 | 50.69 | 0.02514 | 0.49 | 19.58 |

| 35 | 0.00284 | 98,051 | 279 | 489,561 | 4,489,080 | 45.78 | 0.02506 | 0.49 | 19.43 |

| 40 | 0.00425 | 97,773 | 416 | 487,825 | 3,999,519 | 40.91 | 0.02472 | 0.47 | 19.02 |

| 45 | 0.00744 | 97,357 | 724 | 484,975 | 3,511,694 | 36.07 | 0.0241 | 0.44 | 18.42 |

| 50 | 0.01256 | 96,633 | 1,214 | 480,130 | 3,026,719 | 31.32 | 0.02295 | 0.4 | 17.51 |

| 55 | 0.02248 | 95,419 | 2,145 | 471,731 | 2,546,589 | 26.69 | 0.02152 | 0.36 | 16.57 |

| 60 | 0.04876 | 93,274 | 4,548 | 454,999 | 2,074,858 | 22.24 | 0.01914 | 0.29 | 15.35 |

| 65 | 0.08762 | 88,726 | 7,774 | 424,195 | 1,619,859 | 18.26 | 0.0178 | 0.26 | 14.7 |

| 70 | 0.1543 | 80,952 | 12,491 | 373,533 | 1,195,664 | 14.77 | 0.01572 | 0.22 | 14.27 |

| 75 | 0.23139 | 68,461 | 15,841 | 302,703 | 822,131 | 12.01 | 0.01284 | 0.19 | 14.69 |

| 80 | 0.33275 | 52,620 | 17,509 | 219,327 | 519,428 | 9.87 | 0.01052 | 0.18 | 17.01 |

| 85+ | 1 | 35,111 | 35,111 | 300,101 | 300,101 | 8.55 | 0.00961 | 0.21 | 22.23 |

Completely eliminating breast cancer as a cause of death among Kuwaiti females is expected to add almost one-half year to their life expectancy at birth. As well, those who would have died due to breast cancer are expected to live instead an average of 19.7 additional years. Stated differently, if death from breast cancer did not occur, Kuwaiti females who died due to breast cancer would have been expected to live additional twenty years. Although, the impact of the complete elimination of breast cancer might not be sizable (half of a year), it amounts to almost 20 years of life that could be saved.

But off course given the current state of medical know-how, costs, and social and living habits, the total eradication of breast cancer is not feasible and does not seem is true in the foreseeable future despite historical and current medical achievements and advances. Therefore, the analysis provides alternative scenarios of breast cancer percentage eliminations which map into gains of Kuwaiti female life expectancies at various age groups (Table 3).

Briefly, our empirical findings imply that a 10% reduction in deaths attributed to breast cancer would produce a gain of 0.03 of a year (11 days) in life expectancy at age 30. However, when death is reduced by 50% for those at age 30, then it is expected that they would gain 0.14 of a year (51 days). At the same time, Kuwaiti females at age 50 are expected to gain 0.4 (146 days = almost 5 months) when all deaths from breast cancer are controlled. Alternatively, if breast cancer deaths are eradicated more modestly by only 20 percent, life expectancy at the age of 50 would increase by 0.07 of a year (26 days). The findings of other probable scenarios of gains in life expectancies at different age groups for Kuwaiti females are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Years Added to Life Expectancy Among Kuwaiti Females with Elimination Percentages Options

| Age | Life Expectancy | Percentage of Elimination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Elim. | Before Elim. | Diff. | 75% | 50% | 20% | 10% | |

| 30 | 50.69 | 50.19 | 0.49 | 50.56 | 50.44 | 50.29 | 50.24 |

| 35 | 45.78 | 45.3 | 0.49 | 45.66 | 45.54 | 45.39 | 45.34 |

| 40 | 40.91 | 40.44 | 0.47 | 40.79 | 40.67 | 40.53 | 40.48 |

| 45 | 36.07 | 35.63 | 0.44 | 35.96 | 35.85 | 35.72 | 35.67 |

| 50 | 31.32 | 30.92 | 0.4 | 31.22 | 31.12 | 31 | 30.96 |

| 55 | 26.69 | 26.33 | 0.36 | 26.6 | 26.51 | 26.4 | 26.37 |

| 60 | 22.24 | 21.95 | 0.29 | 22.17 | 22.1 | 22.01 | 21.98 |

| 65 | 18.26 | 18 | 0.26 | 18.19 | 18.13 | 18.05 | 18.02 |

| 70 | 14.77 | 14.55 | 0.22 | 14.71 | 14.66 | 14.59 | 14.57 |

| 75 | 12.01 | 11.82 | 0.19 | 11.96 | 11.91 | 11.86 | 11.84 |

| 80 | 9.87 | 9.69 | 0.18 | 9.83 | 9.78 | 9.73 | 9.71 |

| 85+ | 8.55 | 8.33 | 0.21 | 8.49 | 8.44 | 8.38 | 8.35 |

Discussion

Life table techniques are robust statistical method that has been applied extensively in the life time since they combine various mortality rates at different age groups into a single powerful statistical model. One of the most important advantages of life tables over other methodologies in assessing mortality levels is that life tables do not reflect the impact of the actual age distribution of the population; and therefore, they do not require standardization to arrive at acceptable comparison with other populations.

Kuwait’s age-standardized mortality rate of breast cancer according to International Agency for Research on Cancer (2012) was 15.6 per 100,000 which are somewhat higher compared to that of KCR. Kuwait’s rate is similar to other regional rates (i.e. the East Mediterranean Region which has 16 per 100,000). Nevertheless, Kuwait’s rate was higher than that of Western Asia rate (14.4 per 100,000), and much higher than the world wide mortality rate (12.4 per 100,000).

Accordingly, special emphasis ought to be given to prevention, early detection, and treatment. Based on the GLOBOCAN 2012 dataset (2012) for Kuwait, mortality caused by breast cancer constituted 26.7 percent of total cancer deaths. The percentage for Kuwait is considered to be high by international standards. Moreover, Kuwait’s percentage is higher than the East Mediterranean region (24.0 percent), more than Western Asia region percentage (18.7 percent), and is also higher than the overall world percentage (14.7 percent). As noted earlier, breast cancer is the most common among Kuwaiti females, and comparable findings were reported in the literature implying that breast cancer is the most common cancer among females in the GCC comprising almost 15.4% of malignancies among females (GLOBOCAN, 2012).

Invariably, vital statistics always report higher number compared to that of KCR. This has consistently occurred since 1994 although both are produced by MOH. Possible explanations for the discrepancy are: First some cases are not initially included in KCR, secondly there are cases that are treated abroad, and thirdly there are cases quickly became deceased before being included in KCR. Lastly, some have suggested that there is a discrepancy between the clinical records produced by physicians that confirm the rise in number of new reported cases of cancer. Despite this fact, medical statistics produced by the KCCC claim the new reported cancer cases are within international levels (KCCC, 2000-2012).

Disability-Adjusted life years (DALYs) are a metric measure which indicates the overall burden of disease in a given society. It simply expresses the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability, or premature death. According to Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) for 2010 (2014), cancer is not among the three leading causes of DALY in Kuwait and actually is not among the first 25 causes of DALY (GBD, 2014). However, when only years of life lost (YLLs) is considered, it is found the 2 years lost which forms about 1.2% of premature deaths because of breast cancer in 1999, and the number of years lost increased to 3 years in 2010. WHO (2014) estimated Kuwait age-standardized DALY rate 22,068/100,000 in 2000 which declined to 17,433/100,000 in 2012 (http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/mbd/as_daly_rates/atlas.htmal. accessed in 13 August 2014).

The common perception among the “public masses” of cancer as a “death sentence” can and should be changed. Cancer can be treated and its negative impact can be mitigated through simple practices. Many malignancies can be eliminated entirely. Also, up to 30 percent of malignancies can be prevented by introducing simple behavioral and life style changes. Reducing obesity, improving diet, getting regular exercise, and, above all, eliminating or reducing tobacco and alcohol have been proven to lower one’s probability of getting cancer. Obesity in particular poses a high risk to women getting the disease (Friedenreich, 2001). Besides simple daily habits, and genetics are additional critical aspect which requires careful attention. In this regard, breast cancer arises from a multi-factorial process, to include hereditary predisposition, and can be viewed as a disease predominantly influenced by risk factors related to the lifestyle choices (Martin and Weber, 2000). Seafood consumption in Kuwait is found to be a factor in thyroid cancer (Mamon et al., 2002). Genetics, environmental factors, and familial determinates are believed to be responsible for about 15% of all breast malignancies. Therefore, the role of lifestyle along with genetic factors in the etiology of breast cancer need to become better understood in Kuwait.

Public awareness campaigns which inform the public about cancer do yield positive results; however, such campaigns are recent in Kuwait. In fact, there is no national program for breast cancer screening, and no awareness campaigns as such before 2000. Since 2005, breast cancer campaigns became active. For instance it was only recently; in 2006 that Cancer Awareness Nation (CAN) was launched (http://cancampaignkw.com/ar/. Accessed on 19 August 2016.). MOH celebrated awareness campaigns on breast cancer prevention as part of a national program which coincides with Breast Cancer Awareness Month annually in October. Only recently too that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Women Culture and Social Society started to contribute to the nation awareness campaign (http://kwtwcss.org./health-program. Accessed on 19 August 2016.). National companies such as Kuwait Oil Company (KOC) also are active in the campaigns (https://www.kockw.com/sites/EN/Pages/Media%Breseat-Cancer-Awareness_Campaign.aspx. Accessed on 19 August 2016.). Accordingly, there are vigorous attempts to raise the public awareness that are initiated by both public and private organizations. Most people still do not mention the diseases by its proper name; they figuratively refer to cancer as “the other disease” and in fact, they remain petrified of uttering the disease by its actual name. It is perceived as a death sentence. Understandably, there is an extremely negative perception of cancer that exists among the public that causes a high level of fear, shyness, and difficulty in accepting the disease. All of this negative perception and feelings about cancer can be reversed.

A clear and effective dissemination of knowledge about breast cancer would contribute to prevention and eventually reduce the incidence rate. To illustrate, people might not know that breastfeeding, for example, for a period of 12 month reduces breast cancer risk by 4% (Antoniou et al., 2006). This begets another important aspect, that is, cancer surveillance as a necessary step for prevention. In this regard, cancer surveillance alone might not produce desired results as it has to be coupled with powerful political will pack by supportive measures and policies by the Kuwaiti government.

The government for instance ought to institute a well-documented public health policy for chronic diseases. To be successful, such a policy must be backed with political support and a commitment to ensure success. Cancer clinics and facilities must be accessible geographically for the public. Also, developing a research program or center on cancer and developing genetic studies on breast cancer are greatly needed and will enhance the public’s knowledge about epidemiology in Kuwait. Eventually, this warrants further research to identify the risks associated with different malignancies and how to prevent and deal with them. Therefore, allocating more public funds for conducting research on cancer that addresses local needs backed with international collaboration, and the supportive etiological factors behind it, are essential additions.

Developing and maintaining facilities and staff at a highly professional level is a necessity in fighting cancer. Required medical staff and support personnel have to on hand to deliver the desired level of health services. Manpower attraction, training, and skill development are a priority. In fact, a careful analysis of KCCC operations reveals deficiencies in the allocation of financial as well as human resources to provide optimum health care. It is often argued that the availability of radiotherapy services in Kuwait is far below international standards and needs to be raised to meet those standards. Therefore, international standards and guidelines ought to be introduced, adopted, and effectively applied to Kuwait specific circumstances. Safety guidelines have to be followed and the inspection of radiation in cancer treatment facilities has to be conducted. Last but not least, rigorous inspections and regular monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of cancer facilities and instruments concerning safety and radiation must be followed.

As Kuwait goes through demographic and socioeconomic changes, cancer, in general, and breast cancer, in particular, are anticipated to increase, and the social, emotional, and financial burden of cancer on the society will correspondingly increase (Al-Tarawneh et al., 2010). Therefore, ongoing prospective demographic changes in Kuwait have their imprints on the increase of cancer prevalence (Morris et al., 2000). This increase requires serious remedial and follow-up efforts and medical policy attention in order to minimize the negative impact of cancer.

Statement conflict of Interest

The author has no competing or conflict of interests in this paper.

Funding Statement

No funding is involved in conducting this research.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Dr. Ahmed Al-Awadi, Director of Kuwait Cancer Control Center, and Dr. Amani El Basmi, Head of Kuwait Cancer Registry, for their valuable efforts in providing necessary data for the completion of this research.

References

- Al-Shaibani H, Bu-Alayyan S, Habiba S, et al. Risk factors of breast cancer in Kuwait: case-control study. Iran J Med Sci. 2006;26:61–4. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tarawneh M, Khatib S, Arqud K. Cancer incidence in Jordan 1996-2005. Eastern Medit Health J. 2010;16:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen R, Sajnani K, Albassami A. Frequencies of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes in Kuwait: comparisons between different ethnic groups. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:179–84. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou AC, Shenton A, Maher ER, et al. Parity and breast cancer risk among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R72. doi: 10.1186/bcr1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Basmi A, Fayaz M, Al-Mohanadi S, Al-Nesf Y, Al-Awadi A. Reliability of the Kuwait cancer registry: a comparison between breast cancer data collected by clinical oncologists and registry staff. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;22:735–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenreich C. Review of anthropometric factors and breast cancer risk. Euro J of Cancer Prevention. 2001;10:15–32. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLOBOCAN. Data sources and methods. 2012. [Accessed in 8/9/2016]. http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/method/method.asp?country=414 .

- [Accessed on 19 August 2016]. http://cancampaignkw.com/ar/

- [Accessed on 19 August 2016]. http://kwtwcss.org./health-program .

- [Accessed on 19 August 2016]. https://www.kockw.com/sites/EN/Pages/Media%Breseat-Cancer-Awareness_Campaign.aspx .

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (GLOBOCAN) World Fact Statistics 2008. 2008. [Accessed June 6th 2012]. http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheet.asp .

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (GLOBOCAN) Fact Sheet Kuwait 2012. 2012. [Accessed Sep 2016]. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheet_population.aspx .

- Kuwait Cancer Control Center. Kuwait Cancer Registry. Kuwait: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwait Cancer Control Center (KCCC) Kuwait Cancer Registry. Kuwait: Ministry of Health; 2000-2008. For years from 2002 and 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwait Cancer Control Center, Kuwait Registry. Ministry of Health, Kuwait. Global Burden of Diseases, www.healthmetricsandevaluation. GBD Profile: Kuwait. 2000-2012. [accessed in 13 August 2014; accessed on 13 August 2014]. http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/mbd/as_daly_rates/atlas.htmal .

- Mamon A, Varghese A, Suresh A. Benign thyroid and dietary factors in thyroid cancer: a case-control study in Kuwait. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1745–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Weber B. Genetic and hormonal risk factors in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1126–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Kuwait Health. Kuwait, Department of Statistics and Medical Records. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Kuwait Health. Kuwait, Department of Statistics and Medical Records. Various years (2000 to 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Motawy M, El Hattab O, Fayaz S, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to breast cancer management in Kuwait, 1993-1998. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2004;16:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RE, Al Mahmeed Be, Gjorgov AN, Aljazz HG, Al Rashid BA. The epidemiology of head and neck cancer (ICS-O-140-149) in Kuwait 1979-1988. Saudi Dental J. 2000;12:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Omar S, Alieldin N, Khatib O. Cancer magnitude, challenges and control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:1486–96. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.6.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh F, Abdeen S. Pathobiological features of breast tumors in the state of Kuwait: a comprehensive study. Carcinogenesis. 2007;6:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JS, Swanson DA. The methods and materials of demography. Second Edition. New York: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Fact sheet 2015, No. 297. [Accessed September 1 2016]. http://www.who.int/mediacenter/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.