Abstract

Tissue acidosis is a key component of cerebral ischemic injury, but its influence on cell death signaling pathways is not well defined. One such pathway is parthanatos, in which oxidative damage to DNA results in activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and generation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymers that trigger release of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. In primary neuronal cultures, we first investigated whether acidosis per sé is capable of augmenting parthanatos signaling initiated pharmacologically with the DNA alkylating agent, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. Exposure of neurons to medium at pH 6.2 for 4 h after N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine washout increased intracellular calcium and augmented the N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-evoked increase in poly(ADP-ribose) polymers, nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor , and cell death. The augmented nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor and cell death were blocked by the acid-sensitive ion channel-1a inhibitor, psalmotoxin. In vivo, acute hyperglycemia during transient focal cerebral ischemia augmented tissue acidosis, poly(ADP-ribose) polymers formation, and nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor , which was attenuated by a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. Infarct volume from hyperglycemic ischemia was decreased in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1-null mice. Collectively, these results demonstrate that acidosis can directly amplify neuronal parthanatos in the absence of ischemia through acid-sensitive ion channel-1a . The results further support parthanatos as one of the mechanisms by which ischemia-associated tissue acidosis augments cell death.

Keywords: Brain ischemia, hyperglycemia, cell death mechanisms, stroke, cell culture

Introduction

Cerebral ischemia results in tissue acidosis, decreased ATP, increased intracellular Ca2+, and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Depending on the severity and duration of ischemia, neurons may die by caspase-dependent apoptosis, caspase-independent regulated necrosis, or classical necrosis associated with severe cell swelling. However, the contribution of acidosis to particular cell death pathways has not been well studied.

Acidosis by itself can cause cell death in cultured neurons, but the pH of the medium must be very low (pH < 6.2 for < 4 h) or prolonged (pH < 6.6 for > 6 h), if acidosis is more moderate, as typically attained in vivo.1 Therefore, it is more useful to study the modulatory effect of pH on cell death induced by pharmacologic activation of cell death signaling molecules or ischemic insult. The literature on how acidosis modulates apoptosis in neurons is limited and somewhat contradictory, and less is known about how acidosis modulates caspase-independent neuronal death. Acidosis in hippocampal slice cultures can induce both necrosis and apoptosis.2 However, in primary neuronal cultures, acidosis can inhibit apoptosis evoked by serum deprivation.3 Exposure of human NT2-N cultured neurons to staurosporine, which produces caspase-dependent cell death, was unchanged by concurrent acidosis.4 Interestingly, oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) in NT2-N neurons produced caspase-independent cell death that was inhibited by acidosis during the OGD period and potentiated by acidosis during the reoxygenation period in concert with increased ROS.4 Because OGD and focal ischemia both render primarily necrotic morphology, we focused on how acidosis might potentiate caspase-independent cell death signaling.

One pathway of regulated necrosis that has received attention over the past decade is parthanatos.5,6 In this pathway, ROS damage to DNA activates the DNA repair enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which generates poly(ADP-ribose) polymers (PAR polymers). Excessive generation of PAR polymers can stimulate the release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria and its translocation to the nucleus. There, AIF activates an endonuclease to produce large-scale degradation of genomic DNA. This signaling pathway is known to be prominent in male animals undergoing stroke.7,8 However, the influence of acidosis on parthanatos has not been investigated.

To determine whether acidosis can modulate parthanatos directly, we activated parthanatos pharmacologically in primary cortical neuronal cultures and then exposed the neurons to acidic media. The first hypothesis tested was that exposing neurons to acidic medium after inducing DNA damage with a submaximal concentration of the alkylating agent N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) augments the formation of PAR, nuclear translocation of AIF, and eventual neuronal cell death.

Acidosis is known to increase intracellular Ca2+ by a mechanism partly dependent on activation of acid-sensitive ion channel-1a (ASIC1a).9 The second hypothesis tested was that the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin would blunt the component of parthanatos signaling that is augmented by acidosis.

To evaluate whether acidosis augments parthanatos signaling in vivo, we induced acute hyperglycemia as a tool to augment ischemic acidosis. The third hypothesis tested in this study was that acute hyperglycemia before and during transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) augments the formation of PAR polymers and nuclear translocation of AIF. Finally, the last hypothesis tested was that infarct volume is mitigated in PARP1-null (PARP1–/–) mice compared to that in wild-type (WT) mice subjected to hyperglycemic MCAO.

Materials and methods

All procedures on mice were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and the ARRIVE guidelines (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines).

Primary culture of cortical neurons

Primary cortical neurons were cultured from gestational-day 15 embryos of timed-pregnant mice as described.10,11 Cerebral cortices were extracted from embryos under a microscope and incubated for 15 min in trypsin at 37℃. Digested cortices were dissociated by trituration and plated at a density of 920 cells/mm2 on poly-L-ornithine–coated plates. The cells were cultured at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Plating medium consisted of minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 20% horse serum, 30 mM glucose, and 2 mM L-glutamine. After three days in vitro (DIV), growth of non-neuronal cells was halted by exposure to 30 μM 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine solution for four days. Half of the medium was changed once per week. Mature neurons, representing 70–90% of cells, were used at approximately 12 DIV.

Quantification of pH-modulated cell death

To induce submaximal parthanatos, we exposed cortical neurons to 25 µM MNNG at a pH of 7.4 for 15 min. Control neurons were exposed to vehicle (0.1% DMSO) at a pH of 7.4 for 15 min. Vehicle/MNNG was then replaced with medium at a designated pH of 7.4, 6.6, or 6.2 for a 4-h incubation period, after which the medium in all groups was washed with normal pH 7.4 medium. The 4-h duration of acidosis was chosen to simulate the persistent acidosis that has been described after reperfusion from transient MCAO.12 We exposed additional control wells to low pH without exposure to MNNG to confirm that this duration of acidosis by itself did not cause significant cell death within each experiment. To confirm that the component of cell death induced by MNNG and enhanced by acidosis is dependent on PARP and not caspase activation, we pretreated subsets of wells 1 h before MNNG exposure with the PARP inhibitor 3,4-dihydro-5-[4-(1-piperidinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone (DPQ; 30 µM) or the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor Z-VAD.fmk (100 µM). To determine if the acidosis-mediated component of cell death was dependent on ASIC1a, we pretreated subsets of wells with the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin before exposure to vehicle or MNNG and the subsequent 4 h of medium at pH 7.4 or 6.2. In these experiments, non-fixed cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, 7 μM for total nuclei) and propidium iodide (PI, Invitrogen, 2 μM, for dead cell nuclei) for 15 min at 24 h after exposure to DMSO or MNNG. The percent of dead cells was calculated from the ratio of the number of PI-positive nuclei to the number of Hoescht 33342-positive nuclei in three fields per well and three to four wells per experiment. At least three independent experiments were performed for each intervention.

PAR immunoblots

Western blotting was used to measure PAR generation. We exposed the cortical neurons to vehicle or 25 µM MNNG for 15 min and then replaced the medium with that at a designated pH of 7.4 or 6.2. After a 30-min incubation period, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested with NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Equal samples were loaded on 4–12% Tris-glycine gels. Western immunoblotting was performed by standard techniques. Rabbit anti-poly(ADP ribose) polyclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) was used at a dilution of 1:3000. Anti-human β-III tubulin antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA) was used as a protein loading control.

Nuclear AIF

Translocation of AIF to the nucleus was assessed by immunofluorescence. Neurons were exposed to vehicle or MNNG for 15 min followed by exposure to medium with a pH of 7.4 or 6.2. Subsets of wells were treated with the PARP inhibitor DPQ (30 µM), or the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin (0.2 µM; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). At 5 h, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI and an antibody for AIF (Abcam). The percent of cells with overlap of AIF and DAPI staining was blindly quantified from 5 to 7 non-overlapping fields per slide under ×40 objective lens of Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope (Germany) and three to six slides per experiment. Three independent experiments were performed for each intervention.

Ca2+-imaging in live cells

Neuronal cells were plated on 15-mm glass cover slips. On DIV 14, cultured neurons were loaded with 3 µM fura-2AM (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) in Tyrode's solution at 37℃ for 1 h. The composition of Tyrode's solution was 137 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 0.6 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM HEPES, 3 mM NaHCO3, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, and 10 mM glucose at pH 7.4. The cultures were perfused with Tyrode's solution for 5 min to obtain a steady baseline. They were then perfused with 25 µM MNNG for 15 min, followed by Tyrode's solution with a pH of 7.4 or 6.2 for another 40 min. The excitation wavelengths filtered through 340- and 380-nm filters were supplied by a xenon UV lamp. We collected fluorescence intensity through a 510-nm wavelength filter using a cooled CCD digital camera (CoolSNAP, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). [Ca2+]i is presented as the ratio of collected fluorescence intensities of fura-2 excited at 340 and 380 nm (ratio340/380) and processed using MetaFluor 7.0 (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). The ratio340/380 was recorded every 15 s for multiple neurons from at least three separate experiments per group.

MCAO

Transient MCAO was induced with the intraluminal filament technique7 in male Sv/Ev 129 mice weighing 20–28 g (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY). Spontaneously ventilating mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in enriched oxygen. They were kept normothermic while anesthetized. A laser-Doppler flow probe was secured to the skull over the lateral parietal cortex to ensure adequacy of MCAO. Through an incision in the neck, a 7–0 monofilament with the tip enlarged by silicone glue was advanced through the internal carotid artery until perfusion decreased by approximately 80%. Mice without at least a 70% reduction in laser-Doppler flow were excluded. After 45 min of MCAO, the filament was withdrawn to establish reperfusion. Incisions were closed and anesthesia was discontinued.

To produce hyperglycemia, we infused a 25% dextrose solution through a small intraperitoneal catheter. Normoglycemic controls received normal saline. The volume infused was 9 µL/g of body weight over a 30-min period preceding MCAO plus 3 µL/g of body weight over the 45 min of MCAO. The infusion was stopped at reperfusion, and the catheter was removed. In pilot experiments with mice, the blood glucose concentration was 365 ± 72 mg/dL at the end of the dextrose infusion.

3-Amino-m-dimethylamino-2-methylphenazine hydrochloride (neutral red, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) has been used as a pH indicator in the rodent brain.13,14 Separate groups of Sv/Ev 129 mice were used to measure brain pH. They were injected intraperitoneally with 0.5 ml 1% neutral red (in sterile 0.9% saline) at 30 min before MCAO. The control animals for measuring baseline light backscattering were injected with 0.9% saline. The anesthetized mice were decapitated after 45 min of MCAO, and their brains were quickly removed from skulls, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in −80℃. Brains were then cut into 40-µm thick sections on a cryostat at −20℃ starting from bregma 1.18 mm to −0.94 mm.15 Images of brain sections were taken at 250 µm intervals using a digital color camera. Light backscattered from tissue containing neutral red with normal or basic pH shows preferential absorption (ANR)-mediated reduction in the blue bandwidth, whereas light from acidic tissue shows a reduction in the green bandwidth. Therefore, the brain pH can be determined, according to the methods described previously, by comparing relative green-blue absorption of sections to that of known pH levels. Neutral red absorption in proportion to absorption in the absence of neutral red (AT) was calculated using the formula ANR/AT=(IT-INR)/INR. INR and IT are the amount of backscattered light from tissue containing and not containing neutral red, respectively. A standard curve for pH against relative green-blue absorption was plotted using brain homogenates with 15 ppm neutral red at known pH and a best fit algorithm defined for the range of pH 5.0–8.0. Average ipsilateral pH measurements were taken from the 10 images captured for each brain.

PAR was measured by Western blots on tissue harvested at 1 h of reperfusion, when PAR immunoreactivity reaches a peak.7 AIF was measured by Western blots on the nuclear fraction of tissue obtained at 24 ho of reperfusion. Because AIF within the nucleus remains bound, the 24-h measurement represents a time-integral of AIF translocation. Subcellular fractionation was performed with a sucrose gradient technique as previously described.16 Histone was used as a nuclear protein loading control. To determine the PARP dependence of PAR formation and AIF translocation in hyperglycemic mice, we administered the PARP inhibitor DR2313 (2-methyl-3,5,7,8-tetrahydrothiopyrano[4,3-d]pyrimidine-4-one) to mice at the dosing regimen used in rats during MCAO to achieve pharmacologically active concentration in the brain.17 The drug was dissolved in sterile saline at a concentration of 10 mg/mL and infused intravenously at a loading dose of 1 mL/kg before the onset of MCAO, 1 mL/kg/h during MCAO, a repeated bolus of 1 mL/kg just before reperfusion, and 1 mL/kg/h for up to 6 h from the onset of MCAO. This dosing regimen was found to be effective in mice.18

The conversion of dihydroethidium (DHE) to ethidium was used as a marker of ROS generation. DHE was dissolved in DMSO (100 mg/mL), diluted in PBS (1 mg/mL), and infused into a jugular vein (6 µL/g of body weight) at 15 min before MCAO. At 1 h of reperfusion, the anesthetized mice underwent transcardial perfusion with cold PBS until venous return was clear. The brain was quickly harvested, cut into hemispheres, and frozen at −80℃ for later analysis. The tissue was homogenized and extracted with n-butanol under minimal light, and DHE and total ethidium (2-hydroxyethidium and ethidium cation) were separated by HPLC on a Waters Nova-Pak C18 column (3.9 × 150 mm, 5 μm particle size).19,20 Pure acetonitrile (solution B) and 10% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (solution A) were used for the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Separation of the analytes was by stepwise elution, starting with 0% B, increasing linearly to 40% B over 10 min, holding at this proportion for an additional 10 min, and changing to 100% B in 5 min and holding for an additional 10 min.21 Analytes were monitored by fluorescence detection with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 595 nm. Eluates were quantified by comparing integrated peak areas to those of standard solutions22 and normalizing per milligram of protein.

Using WT and PARP1–/– mice bred on an Sv/Ev129 background, we measured infarct volume of cerebral cortex, striatum, and the entire hemisphere at three days of reperfusion on five coronal sections stained with triphenyltetrazolium chloride. Correction for swelling was made by normalizing with the total volume of the ipsilateral structure.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented with mean values and the 95% confidence intervals of the mean values. For each measurement, comparisons among treatment groups were made by an analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the F-value was significant (P < 0.05), the Holm-Sidak procedure was used for multiple comparisons.

Results

Acidosis in cultured neurons

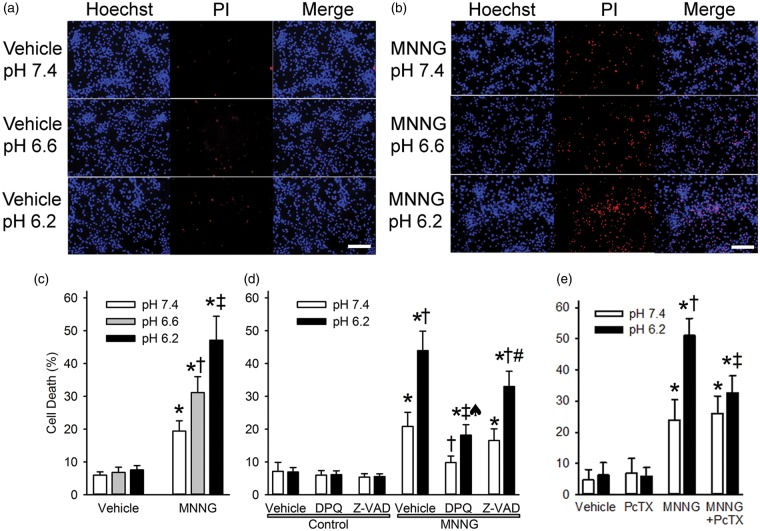

Primary cultured neurons were exposed to a submaximal concentration (25 µM) and duration (15 min) of MNNG or to vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Exposure to medium with a pH of 6.6 or 6.2 for 4 h after vehicle treatment did not discernably increase PI staining (Figure 1(a)). Thus, this severity and duration of acidosis was not sufficient to induce cell death. Treatment with MNNG followed by pH 7.4 medium for 24 h produced moderate increases in PI staining (Figure 1(b)). However, exposure to pH 6.6 medium for 4 h after MNNG increased the number of PI-stained cells at 24 h compared to that observed after 24 h of exposure to pH 7.4 medium, and exposure to pH 6.2 medium led to a further increase in PI staining (Figure 1(b)). Quantification of the number of PI-stained nuclei indicated significant differences among the wells treated with the three different pH levels after MNNG exposure but not among wells treated with the three different pH levels after vehicle treatment (Figure 1(c)). Thus, acidosis dose-dependently enhanced neuronal cell death initiated by MNNG. Subsequent experiments were performed with exposure to a pH of 7.4 in control groups and to a pH of 6.2 in experimental groups.

Figure 1.

Acidosis augments MNNG-induced neuronal cell death. Representative images show propidium iodide staining (PI, red) and Hoechst 33342 nuclear staining (Hoechst, blue) of cultured neurons one day after 15-min treatment with 0.1% DMSO vehicle (a) or 25 µM MNNG (b) followed by 4-h exposure to medium with a pH of 7.4, 6.6, or 6.2 (Scale bar = 200 µm). Note that the proportion of cells stained with PI progressively increased with decreasing pH after MNNG treatment. (c) Mean ± 95% confidence interval of percent cell death at 24 h after treatment with vehicle or MNNG and 4-h exposure to medium with pH 7.4, 6.6, or 6.2 (n = 10 per group). * P < 0.001 from vehicle pH 7.4 treatment; † P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 treatment; ‡ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 and MNNG pH 6.6 treatments. (d) Percent cell death at 24 h after 15-min exposure to vehicle (0.1% DMSO; control) or MNNG followed by 4-h exposure to pH 7.4 or 6.2 medium and continuous treatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), the PARP inhibitor DPQ (30 µM), or the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (100 µM). * P < 0.001 from control pH 7.4 with vehicle treatment; † P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with vehicle treatment; ‡ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 6.2 with vehicle treatment; ♠ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with DPQ treatment; # P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with Z-VAD treatment; n = 9 per group. (e) Percent cell death at 24 h after 15-min exposure to vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or MNNG followed by 4-h exposure to pH 7.4 or 6.2 medium and continuous treatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin (PcTX; 0.2 µM). * P < 0.001 from vehicle pH 7.4 treatment; † P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 treatment; ‡ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 6.2 treatment; n = 6 independent experiments per group.

As expected, treatment with the PARP inhibitor DPQ markedly reduced PI staining after MNNG treatment with normal pH (Figure 1(d)). DPQ also reduced the augmentation of PI staining seen after MNNG treatment with acidotic pH, although the augmentation by acidosis was not completely blocked. In contrast, treatment with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD did not affect the augmentation by acidotic pH. Thus, the augmentation of cell death by acidosis after MNNG exposure is largely PARP-dependent rather than caspase-dependent.

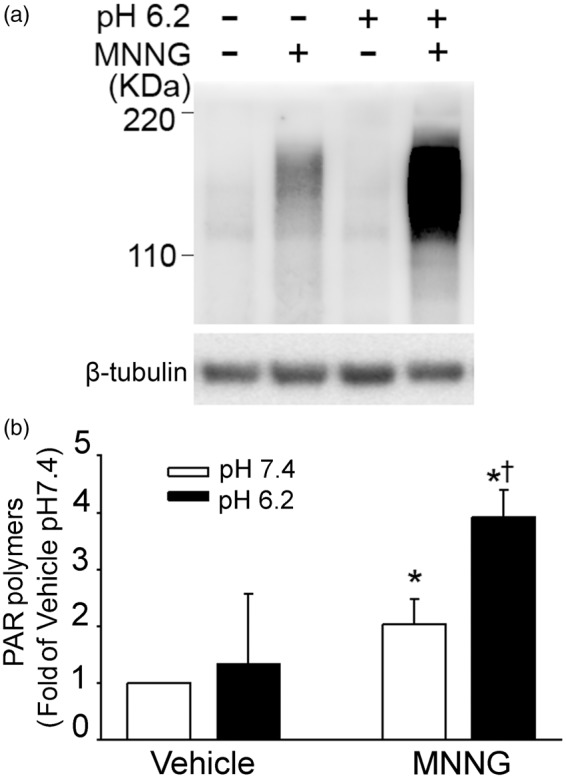

We next examined whether acidosis augmented the formation of PAR polymers. As shown in the Western blot in Figure 2, treatment with MNNG followed by normal pH produced the expected increase in PAR polymers. This increase was augmented in neurons exposed to a pH of 6.2 after MNNG. Quantification of these experiments indicated that exposure to acidic medium after MNNG increased PAR polymers significantly more than did exposure to normal pH after MNNG. Exposure to the acidic medium without MNNG had no effect on PAR polymer expression.

Figure 2.

Acidosis augments MNNG-induced PAR polymer formation. (a) Western blots of PAR polymers from neurons exposed to vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 25 µM MNNG for 15 min followed by medium with a pH of 7.4 or 6.2. (b) Quantification of PAR optical density from neurons exposed to vehicle or MNNG followed by exposure to medium having a pH of 7.4 or 6.2. Data are normalized by optical density of the neurons exposed to vehicle followed by pH 7.4 medium and optical density of β-tubulin and are expressed as means ± 95% confidence interval (n = 3 vehicle groups; n = 6 MNNG groups); * P < 0.01 from vehicle pH 7.4 treatment; † P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 treatment.

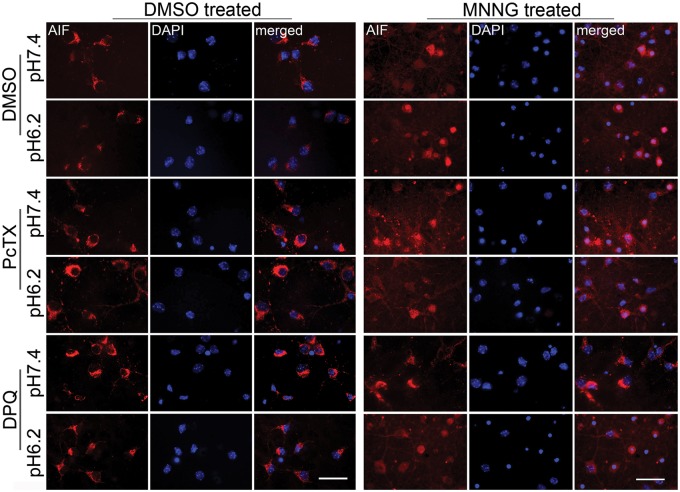

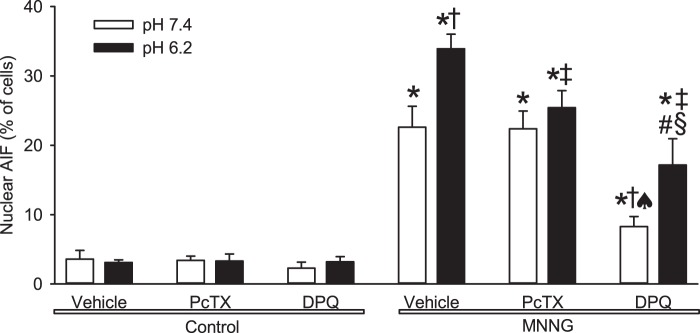

Localization of AIF was examined by immunofluorescence. Confocal images with DAPI showed that AIF remained in the perinuclear cytoplasm during exposure to pH 7.4 or 6.2 medium after vehicle treatment (Figure 3). Consistent with previous work,23 MNNG treatment followed by pH 7.4 increased colocalization of AIF with DAPI. However, the number of cells with colocalization increased further when MNNG treatment was followed by pH 6.2 medium. DPQ suppressed colocalization of AIF with the nuclear stain after MNNG and subsequent exposure to either pH 7.4 or 6.2 medium. Quantification showed statistically significant augmentation of MNNG-induced nuclear staining for AIF with pH 6.2 medium compared to that with pH 7.4 medium (Figure 4). Concurrent treatment with DPQ significantly reduced MNNG-induced nuclear AIF staining with pH 7.4 and 6.2 media compared to the corresponding values without DPQ, although some difference remained between pH 7.4 and 6.2 in the presence of DPQ. Thus, acidosis augmented MNNG-induced nuclear translocation of AIF, and the augmentation was largely dependent on PARP.

Figure 3.

Acidosis augments MNNG-induced nuclear staining of AIF. Representative immunofluorescent images of AIF (red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue) after treatment of neurons with vehicle (0.1% DMSO; left) or 25 µM MNNG (right) followed by medium with a pH of 7.4 or 6.2. Exposure to MNNG followed by pH 7.4 medium increased the number of cells with AIF-DAPI colocalization. The number of cells with colocalization was greater when MNNG was followed by pH 6.2 medium. Concurrent treatment with the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin (PcTX) did not block the AIF-DAPI colocalization when MNNG was followed by pH 7.4 medium but attenuated the colocalization seen when MNNG was followed by pH 6.2 medium. Concurrent treatment with DPQ largely blocked the AIF-DAPI colocalization when MNNG was followed by pH 7.4 medium and attenuated it when MNNG was followed by pH 6.2 medium. Scale bar = 40 µm.

Figure 4.

Quantification of acidosis augmentation of MNNG-induced nuclear translocation of AIF. Percent of cells in which staining for apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) colocalized with the nuclear stain DAPI. Cells were exposed for 15 min to vehicle (0.1% DMSO, control) or MNNG and then to pH 7.4 or 6.2 medium and were treated continuously with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin (PcTX; 0.2 µM), or the PARP inhibitor DPQ (30 µM). Data are shown as mean ± 95% confidence interval.* P < 0.01 from control pH 7.4 with vehicle treatment; † P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with vehicle treatment; ‡ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 6.2 with vehicle treatment; ♠ P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with PcTX treatment; # P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 7.4 with DPQ treatment; § P < 0.001 from MNNG pH 6.2 with PcTX treatment; n = 9 per group.

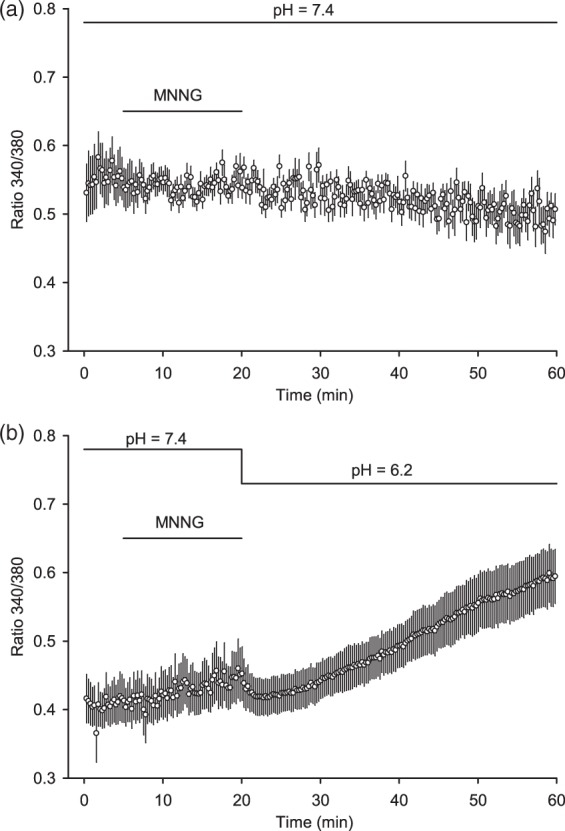

Exposure of neurons to acidic medium is known to increase intracellular Ca2+ by a mechanism dependent on ASIC1a.9 To determine whether acidic medium increases intracellular Ca2+ under conditions of the present experimental paradigm with MNNG treatment, we measured intracellular Ca2+ with fura-2. Exposure to MNNG followed by pH 7.4 medium did not increase intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 5). However, exposure to MNNG followed by pH 6.2 medium produced a progressive increase in the Ca2+ signal. Therefore, the expected effect of acidic medium was present after treatment with MNNG.

Figure 5.

Acidosis after MNNG exposure augments intracellular Ca2+. Fura-2-based intracellular Ca2+ measurements from cultured neurons exposed to MNNG for 15 min followed by medium with pH of 7.4 (a) or 6.2 (b). Values are means ± 95% confidence intervals for 20–22 neurons per group.

To determine whether ASIC1a mediates the acidosis-augmented cell death, we treated neurons with the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin. The inhibitor did not affect the cell death produced by MNNG followed by normal pH, but it blocked the component of cell death that was enhanced by acidosis (Figure 1(e)). Likewise, psalmotoxin had no significant effect on nuclear translocation of AIF induced by MNNG followed by pH 7.4 medium, but it suppressed the increase in nuclear AIF induced by MNNG followed by pH 6.2 to a level similar to that seen with MNNG followed by pH 7.4 medium (Figures 3 and 4). These data are consistent with a mechanism whereby ASIC1a mediates the acidotic augmentation of MNNG-induced AIF nuclear translocation and neuronal cell death.

Hyperglycemia MCAO experiments

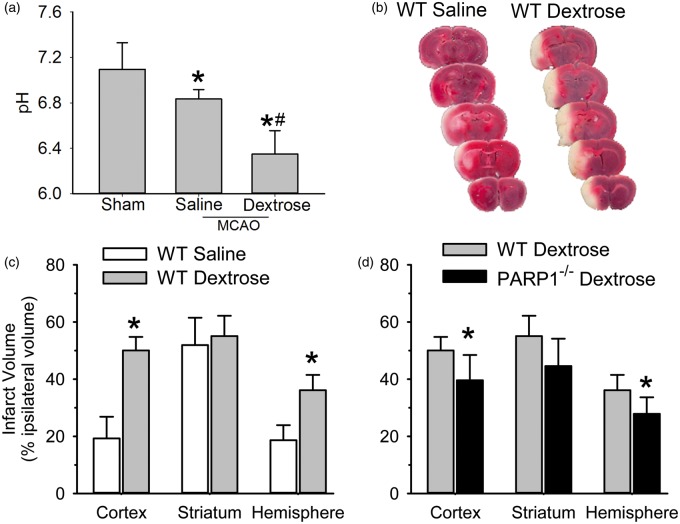

To best reveal the adverse effect of acute hyperglycemia on infarct volume, we chose a relatively brief MCAO duration that produced a submaximal infarct size in control mice. With 45 min of MCAO, mice treated with 25% dextrose infusion before and during MCAO aggravated acidosis in ipsilateral hemisphere and exhibited greater infarct volume in cerebral cortex and the entire hemisphere than did controls infused with saline (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Acute hyperglycemia aggravates brain acidosis in ipsilateral hemisphere and augments infarct volume, which is attenuated in PARP1–/– mice. (a) Changes of brain pH in ipsilateral hemisphere at 45 min middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Mice were infused with saline or dextrose for 30 min before and 45 min during MCAO. Values are means ± 95% confidence intervals of the mean values for three to four animals per groups. * P < 0.05 from sham-operated animals; # P < 0.05 from MCAO animals infused with saline. (b) 3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining of coronal brain sections (1 mm thickness) three days after MCAO in representative wild-type (WT) mice that received an infusion of saline (WT saline) or dextrose (WT Dextrose). (c) Comparison of infarct volume in WT mice that received an infusion of saline (n = 12) or dextrose (n = 12). * P < 0.001 from WT saline. (d) Comparison of infarct volume between WT (n = 12) and PARP1–/– (n = 12) mice that received dextrose infusion. * P < 0.05 from WT dextrose.

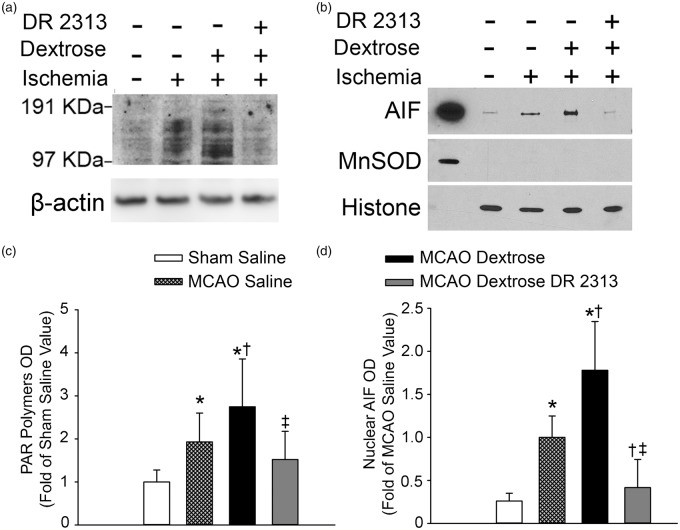

To determine whether acute hyperglycemia augments parthanatos signaling, we measured PAR in brains at 1 h of reperfusion and in sham-operated controls. Immunoblots showed greater PAR expression after MCAO in dextrose-treated mice than in saline-treated mice (Figure 7(a)). Quantification of four independent gels on four separate sets of mice indicated that PAR expression after saline treatment during MCAO was significantly increased compared to that in shams, and that dextrose treatment further augmented this increase (Figure 7(c)). Treatment with the PARP inhibitor DR2313 suppressed the increase in PAR formation associated with hyperglycemic MCAO.

Figure 7.

Acute hyperglycemia augments PAR polymer formation and AIF nuclear translocation after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Western blots of PAR (a) from brain homogenate and of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) (b) from the nuclear fraction of mice that underwent sham surgery with saline infusion or 45-min MCAO with infusion of saline, dextrose, or dextrose plus PARP inhibitor DR2313. Histone was used as a nuclear marker and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) was used as a mitochondrial marker. The left lane is a positive internal control from the mitochondrial fraction of a naïve mouse. (c) Means ± 95% confidence intervals of PAR optical density (OD) from four independent gels. * P < 0.05 from sham saline group; † P < 0.03 from MCAO saline group; ‡ P < 0.01 from MCAO dextrose group. (d) Means ± 95% confidence intervals of AIF OD in the nuclear fraction from five independent gels. * P < 0.002 from sham saline group; † P < 0.005 from MCAO saline group; ‡ P < 0.001 from MCAO dextrose group.

Immunoblots of the nuclear fraction also showed that AIF at one day of reperfusion was more abundant after dextrose treatment than after saline treatment (Figure 7(b)). Results from five independent gels confirmed that nuclear AIF was significantly higher in mice treated with dextrose during MCAO than in mice treated with saline and that nuclear AIF in both groups exceeded values in the sham group (Figure 7(d)). Treatment with DR2313 blocked the increase in nuclear AIF seen after hyperglycemic MCAO.

Acute hyperglycemia is thought to increase production of ROS. After injecting mice with DHE, we measured its conversion to ethidium in the ischemic hemisphere by HPLC. Because the standard deviation increased with the mean value and the distribution was skewed, the data were subjected to a logarithmic transformation before being analyzed by ANOVA. The ethidium level increased significantly from 0.73 ± 0.49 (arbitrary units) in saline-treated mice (n = 5) to 1.33 ± 0.35 in dextrose-treated mice (n = 6). Administration of DR2313 did not reduce the level (1.36 ± 0.37) in dextrose-treated mice (n = 6). Thus, the PARP inhibitor is acting downstream of ROS generation.

Infarct volume was measured in PARP1–/– mice infused with dextrose. Compared to WT mice infused with dextrose, PARP1–/– mice had significantly smaller infarcts in cerebral cortex and in the hemisphere (Figure 6(b)).

Discussion

This study demonstrates several new findings. First, pharmacologic activation of parthanatos by MNNG in cultured neurons is influenced by the subsequent pH. A level of acidosis that can be achieved during severe ischemia augments the formation of PAR polymers, the nuclear translocation of AIF, and neuronal cell death. Second, the component of AIF nuclear translocation and neuronal cell death that is augmented by acidosis after MNNG is dependent on activation of ASIC1a and is associated with increased intracellular Ca2+. Third, acute hyperglycemia during focal ischemia augments the formation of PAR polymers and the PARP-dependent translocation of AIF to the nucleus. Fourth, the increase in infarct volume associated with hyperglycemia is partly dependent on PARP1.

Acidosis has long been recognized as a major factor that contributes to cerebral ischemic injury,24–26 but the downstream cell death effector mechanisms recruited by acidosis have not been well explored. Our in vitro data show that acidosis can amplify parthanatos signaling and augment neuronal cell death. We chose a 4-h duration of acidosis to mimic the duration of tissue acidosis reported during reperfusion after MCAO.12 The 4-h exposure to a pH of 6.2 by itself was not sufficient to induce neuronal cell death. Thus, the augmentation of MNNG-induced cell death by acidosis represents a true interaction of parthanatos and acidosis and not simply an independent additive effect.

Exposure to MNNG followed by incubation in medium of normal pH did not increase intracellular Ca2+, whereas exposure to MNNG followed by pH 6.2 medium produced a gradual increase in intracellular Ca2+. We would expect the increased Ca2+ to lead to increased ROS, which likely enhanced the MNNG-induced damage to DNA and consequent activation of PARP. The greater PAR polymer expression observed with acidosis after MNNG is consistent with greater activation of PARP after exposure to an acidic medium. PAR polymers can bind to AIF in the mitochondria and cause release of AIF.5,6,27 Thus, the enhancement of nuclear AIF that we observed after cells were exposed to MNNG followed by acidic medium is also consistent with this hypothesis.

ASIC1a is sensitive to extracellular pH below 7.0.28 Its activation permits entry of Ca2+ and Na+, which can also lead to increased Ca2+ entry via the Na/Ca exchanger. Xiong et al.9 showed that the ASIC1a inhibitor psalmotoxin was able to block the increase in intracellular Ca2+ caused by neuronal exposure to pH 6.0. Our observation is consistent with studies of neurons exposed to acidic medium without prior MNNG treatment. Furthermore, psalmotoxin blocked the ability of MNNG followed by acidic medium to augment nuclear AIF and neuronal cell death beyond that seen with MNNG followed by pH 7.4. Assuming that MNNG does not directly sensitize ASIC1a, these data indicate that ASIC1a contributes to the acidosis modulation of parthanatos cell death.

To help validate the role of acidosis in amplifying parthanatos signaling during cerebral ischemia in vivo, we used acute hyperglycemia, which is well known to enhance metabolic acidosis during cerebral ischemia and to delay recovery of tissue pH during reperfusion.29,30 As expected, we found that dextrose treatment before and during the 45-min period of MCAO enhanced the decrease in brain pH. It also augmented the ischemia-induced increase in PAR polymers and nuclear AIF. Moreover, administration of a PARP inhibitor largely blunted these increases. Hence, these in vivo data support the hypothesis that acidosis during and after ischemia contributes to parthanatos cell death signaling.

The fact that infarct volume was significantly smaller in PARP1–/– mice treated with dextrose than in WT mice treated with dextrose also indicates that parthanatos contributes to neuronal cell death. However, the reduction in infarct volume measured at three days of reperfusion in PARP1–/– mice was moderate, suggesting that other mechanisms come into play in vivo. For example, mobilization of iron stores,31,32 depletion of glutathione,33 and augmentation of ROS by acute hyperglycemia during reperfusion34,35 may be sufficiently severe to disrupt cell organelles,25 produce profound cell swelling, and lead to classical necrosis even when parthanatos is blocked. In our model, we confirmed that acute hyperglycemia augmented ROS,34 as indicated by the conversion of DHE to ethidium. Thus, the increase in ROS may not only damage DNA and activate PARP1, but may also damage cell membranes, including the nuclear envelope.

In addition, alternative forms of regulated cell death may be invoked when parthanatos is blocked. For example, acidosis can promote apoptosis in specific experimental paradigms in vitro.2,36 Hyperglycemia also produces effects that can impact stroke outcome by mechanisms other than increased lactic acidosis.37,38 Thus, our data do not exclude multiple cell death pathways being recruited by acidotic- and non-acidotic-related mechanisms during hyperglycemic ischemia.

Although our in vitro experiments focused on neurons, hyperglycemia during focal ischemia also augments endothelial damage and increases blood–brain barrier permeability.34,39 Inhibition of PARP can also reduce inflammation,40 and part of the protective effect in PARP–/– mice in vivo might have been mediated by effects on other cell types such as microglia41 and astrocytes.42

Of note, we performed the in vivo experiments on male mice, in whom caspase-independent parthanatos is known to be a major contributor to neuronal injury from normoglycemic ischemia.8 In female mice, caspase-dependent apoptosis may play a greater role.43 Thus, the mechanism by which acidosis amplifies cell death may differ in females. We did not investigate the details of how acidosis would augment canonical apoptosis because this study was designed to focus on the interaction of acidosis with parthanatos.

In summary, our results demonstrate that exposure of neurons to acidic conditions after treatment with a DNA alkylating agent augments intracellular calcium, formation of PAR polymers, translocation of AIF to the nucleus, and cell death. The component of AIF translocation and cell death that was augmented by low pH was dependent on ASIC1a, which is known to contribute to calcium entry during acidosis. Consistent with these in vitro data showing acidosis amplification of parthanatos signaling, acute hyperglycemia before and during MCAO augmented PAR, nuclear AIF translocation, and infarct volume in a PARP-dependent manner. Therefore, parthanatos is capable of contributing to the component of cell death associated with acidosis during cerebral ischemia.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS067525 (T.M.D., R.C.K.), DA00266 (T.M.D., V.L.D.), NS039148 (V.L.D.), and NS086953 (S.A.A.), an American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Beginning Grant-in-Aid (13BGIA16850043 Z.-J.Y.), and an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (X.L., S.A.A.). T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors' contributions

JZ and XL: contributed equally to this article. XL, RCK, Z-JY conceived and designed the experiments. JZ, XL, HK, YTK, LY, GH, and Z-JY performed the experiments. RCK and Z-JY analyzed the data. SAA, VLD, and TMD provided oversight for the project. RCK and Z-JY compiled manuscript and figure preparation.

References

- 1.Nedergaard M, Goldman SA, Desai S, et al. Acid-induced death in neurons and glia. J Neurosci 1991; 11: 2489–2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding D, Moskowitz SI, Li R, et al. Acidosis induces necrosis and apoptosis of cultured hippocampal neurons. Exp Neurol 2000; 162: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu L, Glassford AJ, Giaccia AJ, et al. Acidosis reduces neuronal apoptosis. Neuroreport 1998; 9: 875–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almaas R, Pytte M, Lindstad JK, et al. Acidosis has opposite effects on neuronal survival during hypoxia and reoxygenation. J Neurochem 2003; 84: 1018–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer is a death signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 18308–18313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Kim NS, Haince JF, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding to apoptosis-inducing factor is critical for PAR polymerase-1-dependent cell death (parthanatos). Sci Signal 2011; 4: ra20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Klaus JA, Zhang J, et al. Contributions of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and -2 to nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor and injury from focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurochem 2010; 113: 1012–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullough LD, Zeng Z, Blizzard KK, et al. Ischemic nitric oxide and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in cerebral ischemia: male toxicity, female protection. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005; 25: 502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong ZG, Zhu XM, Chu XP, et al. Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell 2004; 118: 687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson VL, Kizushi VM, Huang PL, et al. Resistance to neurotoxicity in cortical cultures from neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. J Neurosci 1996; 16: 2479–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Yu SW, Koh DW, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor substitutes for caspase executioners in NMDA-triggered excitotoxic neuronal death. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10963–10973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pignataro G, Simon RP, Xiong ZG. Prolonged activation of ASIC1a and the time window for neuroprotection in cerebral ischaemia. Brain 2007; 130: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaManna JC, McCracken KA. The use of neutral red as an intracellular pH indicator in rat brain cortex in vivo. Anal Biochem 1984; 142: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendall GS, Hristova M, Zbarsky V, et al. Distribution of pH changes in mouse neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic insult. Dev Neurosci 2011; 33: 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates., 3rd ed Amsterdam: Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Nemoto M, Xu Z, et al. Influence of duration of focal cerebral ischemia and neuronal nitric oxide synthase on translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor to the nucleus. Neuroscience 2007; 144: 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakajima H, Kakui N, Ohkuma K, et al. A newly synthesized poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, DR2313 [2-methyl-3,5,7,8-tetrahydrothiopyrano[4,3-d]-pyrimidine-4-one]: pharmacological profiles, neuroprotective effects, and therapeutic time window in cerebral ischemia in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 312: 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Z, Zhang J, David KK, et al. Endonuclease G does not play an obligatory role in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-dependent cell death after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2010; 299: R215–R221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaura K, Gebremedhin D, Zhang C, et al. Contribution of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to the hypoxia-induced activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel current in cultured rat hippocampal astrocytes. Neuroscience 2006; 143: 703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. The confounding effects of light, sonication, and Mn(III)TBAP on quantitation of superoxide using hydroethidine. Free Radic Biol Med 2006; 41: 1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandes DC, Wosniak J, Jr., Pescatore LA, et al. Analysis of DHE-derived oxidation products by HPLC in the assessment of superoxide production and NADPH oxidase activity in vascular systems. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007; 292: C413–C422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zielonka J, Zhao H, Xu Y, et al. Mechanistic similarities between oxidation of hydroethidine by Fremy's salt and superoxide: stopped-flow optical and EPR studies. Free Radic Biol Med 2005; 39: 853–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, et al. Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science 2002; 297: 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siesjo BK. Acidosis and ischemic brain damage. Neurochem Pathol 1988; 9: 31–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalimo H, Rehncrona S, Soderfeldt B, et al. Brain lactic acidosis and ischemic cell damage: 2. Histopathology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1981; 1: 313–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins NM, Swanson RA. Opposing effects of glucose on stroke and reperfusion injury: acidosis, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism. Stroke 2014; 45: 1881–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu SW, Andrabi SA, Wang H, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor mediates poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 18314–18319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channels: advances, questions and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Neurosci 2006; 29: 578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehncrona S, Rosen I, Siesjo BK. Brain lactic acidosis and ischemic cell damage: 1. Biochemistry and neurophysiology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1981; 1: 297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurn PD, Koehler RC, Norris SE, et al. Dependence of cerebral energy phosphate and evoked potential recovery on end-ischemic pH. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1991; 260: H532–5H41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurn PD, Koehler RC, Blizzard KK, et al. Deferoxamine reduces early metabolic failure associated with severe cerebral ischemic acidosis in dogs. Stroke 1995; 26: 688–694. discussion 94–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipscomb DC, Gorman LG, Traystman RJ, et al. Low molecular weight iron in cerebral ischemic acidosis in vivo. Stroke 1998; 29: 487–492. discussion 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying W, Han SK, Miller JW, et al. Acidosis potentiates oxidative neuronal death by multiple mechanisms. J Neurochem 1999; 73: 1549–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, et al. Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke 2007; 38: 1044–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bemeur C, Ste-Marie L, Montgomery J. Increased oxidative stress during hyperglycemic cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int 2007; 50: 890–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aoyama K, Burns DM, Suh SW, et al. Acidosis causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and caspase-12-mediated astrocyte death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005; 25: 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schurr A, Payne RS, Miller JJ, et al. Preischemic hyperglycemia-aggravated damage: evidence that lactate utilization is beneficial and glucose-induced corticosterone release is detrimental. J Neurosci Res 2001; 66: 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin A, Rojas S, Chamorro A, et al. Why does acute hyperglycemia worsen the outcome of transient focal cerebral ischemia? Role of corticosteroids, inflammation, and protein O-glycosylation. Stroke 2006; 37: 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV, Stamatovic SM, et al. Ischemia-induced endothelial cell dysfunction. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2005; 95: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamby AM, Suh SW, Kauppinen TM, et al. Use of a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor to suppress inflammation and neuronal death after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Stroke 2007; 38: 632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kauppinen TM, Swanson RA. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 promotes microglial activation, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated neuron death. J Immunol 2005; 174: 2288–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alano CC, Ying W, Swanson RA. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-mediated cell death in astrocytes requires NAD+ depletion and mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 18895–18902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu F, Li Z, Li J, et al. Sex differences in caspase activation after stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 1842–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]