Abstract

[11C]Ro15-4513 has been introduced as a positron emission tomography radioligand to image the GABAAα5 receptor subtype thought to be important in learning, memory and addiction. However, the in vivo selectivity of the ligand remains unknown and a full assessment of different analysis approaches has yet to be performed. Using human heterologous competition data, with [11C]Ro15-4513 and the highly selective GABAAα5 selective negative allosteric modulator Basmisanil (RG1662), we quantify the GABAAα5 selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513, assess the validity of reference tissues and evaluate the performance of four different kinetic analysis methods. The results show that [11C]Ro15-4513 has high but not complete selectivity for GABAAα5, with α5 representing around 60–70% of the specific binding in α5 rich regions. Competition data indicate that the cerebellum and pons are essentially devoid of α5 signal and might be used as reference regions under certain conditions. Off-target non-selective binding to other GABAA subtypes means that the choice of analysis method and the interpretation of outcome measures must be considered carefully. We discuss the merits of two tissue compartmental model analyses to derive both VT and VS, band-pass spectral analysis for estimation of and the simplified reference tissue model for estimation of .

Keywords: γ-Aminobutyric acid, kinetic analysis, positron emission tomography, quantification, selectivity

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most abundant and influential inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Investigation of the GABA system in humans in vivo has been made possible, through the development of radioligands selective for the allosteric benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor, with positron emission tomography (PET). PET radioligands for the benzodiazepine site have been developed with good brain penetration, specific binding and reversible kinetics, though in most cases with a degree of non-selectivity for GABAA receptor subtypes. The best known example is [11C]Ro15-1788 (or [11C]flumazenil), which is a non-selective benzodiazepine antagonist with similar affinities for the GABAAα1,2,3,5 subtypes. The non-selective nature of [11C]flumazenil means that the PET signal is a composite of the local subtype concentrations, which vary regionally and between clinical populations. The heterogeneous regional distribution of the different benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA subtypes, as well as their markedly different functional roles, has led to the search for more selective ligands. The extrasynaptic GABAAα5 receptor has been of particular interest due to its putative role in learning, memory and addiction.

The imidazodiazepine Ro15-4513 is a partially selective inverse-agonist for the GABAAα5 receptor, developed in the 1980s by Roche for the labelling of benzodiazepine sites and therefore, by allosteric interaction, the GABA/benzodiazepine complex.1 Originally applied for visualisation of receptor sites in the rodent brain,2 Ro15-4513 later epitomised the concept of inverse agonism after demonstrating inhibition of the behavioural intoxication effects of ethanol.3,4 When labelled with carbon-11, Ro15-4513 has been used as a PET radioligand to enable investigation of the GABAAα5 receptor subtype and its dysregulation in a number of disorders including addiction. However, whilst kinetic analysis methods have been developed previously in order to try to isolate the GABAAα5 component of the signal,5,6 the true in vivo selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 and the magnitude of the GABAAα5 specific signal have yet to be fully characterised in vivo in man.

Autoradiography studies confirm that [11C]Ro15-4513 has partial selectivity for the GABAAα5 receptor subtype, with an affinity, Ki, approximately 20-fold greater over the other GABAA subtypes (∼10 nM GABAAα1,2,3; ∼0.5 nM GABAAα5).7,8 The high proportion of α5-specific signal, and its subcortical localisation, were demonstrated using the highly selective ligands RY80 and L655,708 in the rat,9 though it has also been suggested that there is some binding to the benzodiazepine-insensitive GABAA subtypes GABAAα4 and GABAAα6, shown with high concentrations of diazepam and GABA.10

A portion of cerebellum binding of [11C]Ro15-4513 has been shown to be displaceable by the benzodiazepines flumazenil and clonazepam both in vitro and in vivo in non-human primates and humans.11,12 Furthermore, the relatively high concentrations of GABAAα1,2,3 demonstrated by autoradiography, particularly in the cortex and cerebellum,13 suggest that despite a lower relative affinity, there will be some measurable signal from these sites due to a greater .

To date, quantification of dynamic [11C]Ro15-4513 PET data in non-human primates and humans has been undertaken in several ways. Initial validation of the ligand involved homologous and heterologous competition studies with clonazepam in non-human primates.11,14 These studies identified regions of the brain in which heterologous and homologous blockade differs, suggesting that [11C]Ro15-4513 has specific binding targets not including those of other non-selective benzodiazepine agents. In humans, 2TCM quantification of VT revealed a pattern of differing tissue kinetics, suggesting regionally heterogeneous binding.15 Similarly, application of spectral analysis for parametric mapping of [11C]Ro15-4513 VT in humans in vivo, identified its primarily limbic distribution.9

The relatively low signal in the white matter, particularly the pons, suggested that this might be a suitable reference region for methods such as the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM), to avoid arterial sampling.16 The presence of low signal alone is not sufficient to validate the region as an appropriate reference region and thus this method could underestimate target binding with some level of bias.17,18 Using [11C]flumazenil, for example, application of SRTM with the pons as a reference tissue performed poorly in test–retest and in clinical identification of hippocampal sclerosis.19,20 Given the proposed lack of GABAAα5 in the cerebellum, this provides an alternative candidate reference region for investigation.

To fully characterise both the selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 for the GABAAα5 subtype and evaluate whether there is a suitable reference tissue devoid of specific binding, heterologous competition studies with a selective GABAAα5 compound are required. We were provided access to a dataset previously acquired by F. Hoffmann-La Roche consisting of dynamic [11C]Ro15-4513 PET data measured in healthy human subjects following a range of doses of the highly selective GABAAα5 selective negative allosteric modulator Basmisanil.21,22

In this article, we use these heterologous competition data to: (a) elucidate the true regional in vivo selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 for the GABAAα5 receptor, (b) assess the validity of the cerebellum and pons as reference tissues and (c) evaluate the merits of different analytical techniques for quantifying GABAAα5 receptor availability from a dynamic [11C]Ro15-4513 PET scan.

Materials and methods

Data set

Data were taken from a PET study commissioned by F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland), which was performed by Hammersmith Imanet (Hammersmith, London, UK). The study was approved by the London-Brent research ethics committee, by the UK Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee and conducted under ICH GCP guidelines. The study from which our dataset is drawn aimed to evaluate receptor occupancy, which is not reported here.

Ten healthy male volunteers, who had provided informed consent, underwent three [11C]Ro15-4513 PET scans, one at baseline and two, at 3 and 9 h, following the administration of one of four separate doses (2 × 15 mg, 2 × 60 mg, 3 × 130 mg, 3 × 1250 mg) of the α5-selective negative allosteric modulator Basmisanil. Unavailability of baseline scan data for one subject led to this subject being excluded from our analyses. [11C]Ro15-4513 was synthesised by N-methylation of the N-desmethyl derivative with [11C]iodomethane,1 and was administered through an intravenous cannula in the dominant vein of the antecubital fossa (372 ± 5 MBq in 4.68 ± 2.90 ml).

Dynamic PET scans were acquired over 90 min using a Siemens ECAT EXACT HR + (CTI/Siemens, model 962; Knoxville, TN, USA) scanner, with 63 transaxial image planes covering an axial field of view of 15.5 cm. PET emission data were corrected for attenuation and scatter using a 10-min transmission scan and reconstructed using Fourier rebinning and 2D filtered backprojection with a 2.0 mm kernel Ramp filter, into 24 dynamic frames (1 × 30, 4 × 15, 4 × 60, 2 × 150, 10 × 300 and 3 × 600 s). The final reconstructed volume had voxel dimensions of 2.094 × 2.094 ×2.42 mm3. All subjects also underwent T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a Philips 1.5 T Gyroscan Intera scanner (Philips, Best, The Netherlands) to provide anatomical images to aid in region definition.

Each subject had a radial arterial cannula inserted to allow for measurement of the arterial blood radioactivity concentration. For the first 15 min, continuous sampling was employed. Discrete blood samples were also taken at 4, 6, 8, 10, 20, 35, 50, 65, 80 and 90 min to measure the total plasma radioactivity concentration, whole blood radioactivity concentration and the parent fraction in plasma. Plasma concentrations of Basmisanil were measured at the start and end of each scan.

Data analysis: [11C]Ro15-4513 dynamic scans

For analysis, we used the PET data analysis and kinetic modelling toolkit, MIAKAT™ (www.miakat.org23) which also uses software from SPM5 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging) and FSL (FMRIB, University of Oxford) and is implemented in MATLAB® (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

The brain was initially extracted from the T1-weighted MR image. Frame-by-frame motion correction of the dynamic PET data was performed using mutual information co-registration of the individual frames to a reference frame (frame 16). An average motion-corrected PET image was generated and used for co-registration with the extracted T1-weighted MR brain image. The CIC neuroanatomical atlas24 was non-linearly registered to the individual’s extracted brain, via non-linear registration of the T1 anatomical images, to generate a personalised set of anatomically parcellated regions. Finally, regional tissue time-activity curves (TACs) were generated from this parcellation for a set of regions of interest (ROI) with varying signal strengths and GABAAα5 density; insular cortex, anterior cingulate, cingulate cortex, occipital lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, parahippocampal gyrus, cerebellum, nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, amygdala, caudate, putamen, thalamus, midbrain, medulla, pons.

The total plasma radioactivity was estimated by multiplying the whole blood radioactivity time course by a sigmoid model (equation (1)) that had been fitted to the discrete plasma:blood (POB) ratio. The parent plasma arterial input function was then generated by multiplying these data with a continuous estimate of the parent fraction. The parent fraction data were fit to the same sigmoid equation (1).

| (1) |

where Y is the estimated POB or parent fraction, t is time and are parameters estimated by a nonlinear least-squares curve fit. The resulting plasma arterial input function was then smoothed post peak using a tri-exponential fit. A delay correction was performed for each scan to account for any temporal delay between blood sample measurement and the tomographic measurements of the tissue data.

One (1TCM) and two (2TCM) tissue compartment plasma input models were fitted to the regional PET time activity data, with a fitted blood volume term, to identify an appropriate kinetic model and to subsequently derive estimates of VT for each ROI. All tissue and input function measurements were corrected for radioactive decay.

Data analysis: [11C]Ro15-4513 specific binding and selectivity

VT values obtained from the 2TCM were analysed, across all subjects and doses for the 18 ROIs, using a single-site competition model (see equation (2)).

| (2) |

where is the total volume of distribution in a region, is the specific GABAAα5 volume of distribution in a region, is the measured plasma concentration of Basmisanil, is the half-maximal effective concentration of the drug and is the remaining volume of distribution after accounting for the GABAAα5 signal in a region. contains both the non-displaceable and the non-GABAAα5 specific volume of distribution in a region . All regions were fitted simultaneously, with shared across all regions, to estimate regional estimates of and using nonlinear regression. was estimated from the measured plasma concentration of Basmisanil at the start of the scan (although the concentration was fairly stable throughout with a mean change of −3.5% between scan start and scan end).

Subsequently, a regression analysis of the regional values with literature values of [11C]flumazenil binding potential (BPND)25 was performed to estimate the global value and hence the regional non-GABAAα5 specific binding, under the assumption that the off target binding was equivalent to that measured with [11C]flumazenil and that is invariant across regions. The value was optimised, allowing for a proportionality constant to identify the value which maximised the agreement between and [11C]flumazenil across regions according to equation (3).

| (3) |

Having estimated , and , it was then possible to calculate the regional selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513. For visual representation of these data, parametric mapping of and was also investigated using a basis function approach to fit equation (2) at the voxel level. Estimates of and were both fixed to the values derived from the ROI analysis. Parametric maps of VT were generated for each scan in a two-stage process; first, a basis function 1TCM parametric imaging routine was employed because of its robustness to noise, and second, the 1TCM bias was corrected by applying the regression factor derived from the 1TCM vs. 2TCM regional regression analysis to obtain corrected 2TCM VT parametric images These images were then non-linearly registered into MNI space, using the structural T1 data to derive appropriate non-linear deformation parameters. Finally, the basis function implementation of equation (2) (with a basis term for and a unity basis term for ) was fitted to these data at each voxel using a non-negative least-squares algorithm to generate parametric images of and .

| (4) |

subject to

Evaluation of [11C]Ro15-4513 analysis approaches

Four analysis approaches, which have been previously proposed for the analysis of [11C]Ro15-4513, were investigated in the context of the gold standard regional GABAAα5 binding data () determined in the previous section. For these comparisons, mean regional outcome measures were calculated from the nine baseline scans.

Method I (2TCM – VT)

VT was derived from the 2TCM. In more detail, the time-activity curves were fitted by a convolution of the arterial plasma parent input function with an impulse response function comprising a sum of two exponentials, with a fitted blood volume (see equation (5)).

| (5) |

where is the measured PET radioactivity data at time-point t, VB is the estimated blood volume, CB is the concentration of radioactivity in whole blood, CP is the concentration of radioactivity in the plasma, and φ and θ represent functions of the microparameters (), substituted for clarity.26 At equilibrium, the ratio of parent tissue to plasma concentration of radioactivity is the total volume of distribution (or partition coefficient), VT, which can be calculated as,

| (6) |

Method II (2TCM – VS)

VS, the volume of distribution of the second tissue compartment in the 2TCM, was estimated from the individual rate constants obtained from the 2TCM fit according to,

| (7) |

Method III (spectral analysis – )

Previously, spectral partitioning of the [11C]Ro15-4513 kinetic components using spectral analysis27 has been proposed as a method to estimate directly.5,6 One hundred exponential functions were generated, with the decay parameter logarithmically distributed between 0.00006371 and 1 s−1,28 and convolved with the arterial parent plasma input function to generate a set of kinetic basis functions. A non-negative least-squares algorithm was then used to fit this over-complete basis set to the measured data.

| (8) |

subject to A bandpass approach was used based on the slow kinetic component seen in high GABAAα5 density regions, and the zolpidem-induced reduction in the fast kinetic components of the spectrum.6 Thus, an integral of the slow kinetic component of the spectrum has been hypothesised to relate to GABAAα5 binding, and is estimated according to equation (9). The slow component band was defined by the limits a( = 0.00006371 s−1) and b(= 0.001 s−1).

| (9) |

Method IV (SRTM – )

was estimated using the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) with both the cerebellum and pons as alternative reference tissues.29 The basis function implementation of SRTM was used for parameter estimation,30

| (10) |

where CR is the measured radioactivity concentration in the reference tissue, Bi is a basis function comprising a convolution of CR and an exponential and are parameters used to derive , R1 and k2.

For each of the four analysis methods, the relationship between the outcome measure and the gold standard was assessed using linear regression and the Pearson’s square of residuals, R2.

Results

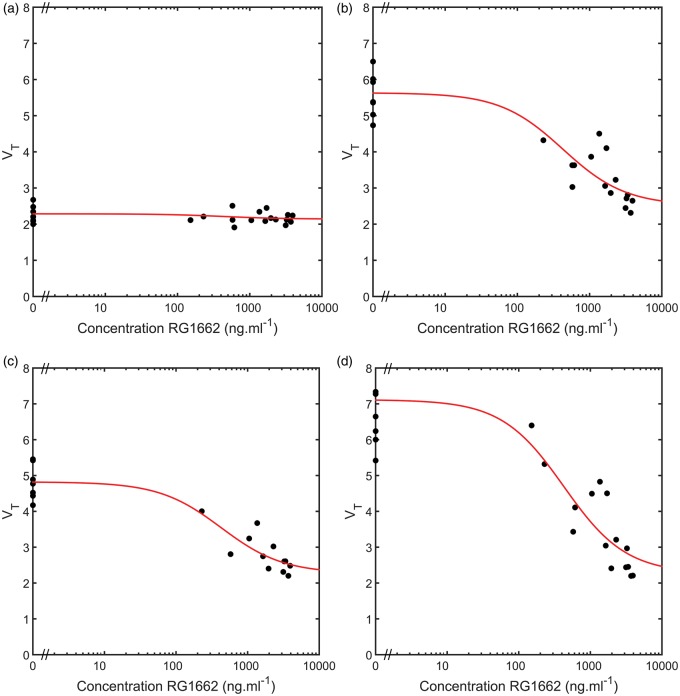

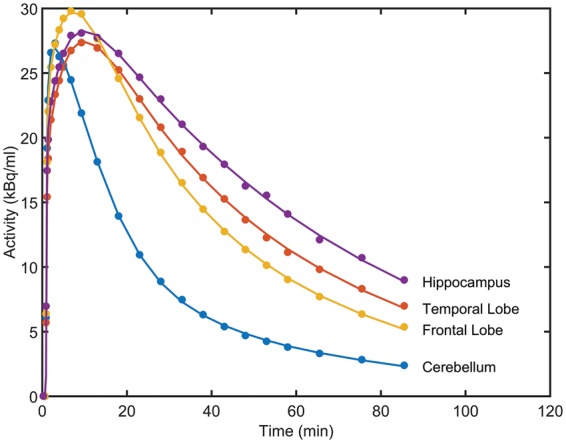

The results from fitting the 1TCM and 2TCM models to the 18 chosen ROIs are given in Table 1. In almost all regions, the 2TCM performed better according to the Akaike information criterion, with the four regions for which the two models performed equally well being the four with the lowest specific signal, as expected. The 2TCM was therefore chosen as the best model to describe the radioligand kinetics across the brain, and compartmental modelling parameters quoted henceforth are derived using 2TCM. K1 is high and relatively constant across the brain (∼0.4 ml cm3 min−1) consistent with a single pass extraction of at least 50%. No effect of drug was seen on K1 in any region (Student’s t-test: t < 0.55, p > 0.64 in all ROIs). Examples of 2TCM fits in the cerebellum, a region largely devoid of GABAAα5, and the temporal lobe, frontal lobe and hippocampus, where density is high, are given in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Regional [11C]Ro15-4513 parameters derived from 2TCM and competition binding analysis.

| Model selection | 2TCM |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI |

AIC |

VT baseline |

K1 baseline (ml·min−1·cm−3) |

K1 drug (ml·min−1·cm−3) |

(ml·cm−3) |

a (ml·cm−3) |

|

|

||

| 1TCM | 2TCM | Diff | Mean [±95% CI] | Mean [±95% CI] | Mean [±95% CI] | Mean [±95% CI] | Mean [±95% CI] | |||

| Insular ctx | −141.5 | −169.2 | 27.6 | 8.97 [7.16, 10.78] | 0.42 [0.39, 0.45] | 0.42 [0.39, 0.45] | 4.86 [4.29, 5.44] | 2.05 [1.61, 2.49] | 0.77 | 0.70 |

| Anterior cingulate | −147.0 | −171.7 | 24.7 | 7.16 [6.75, 7.57] | 0.4 [0.37, 0.43] | 0.4 [0.38, 0.42] | 4.38 [3.81, 4.95] | 1.92 [1.49, 2.35] | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| Cingulate ctx | −147.2 | −167.7 | 20.4 | 6.46 [6.07, 6.85] | 0.39 [0.36, 0.42] | 0.41 [0.38, 0.44] | 3.75 [3.19, 4.31] | 1.88 [1.47, [2.30] | 0.87 | 0.67 |

| Occipital lobe | −171.3 | −181.1 | 9.7 | 4.37 [4.17, 4.57] | 0.4 [0.37, 0.43] | 0.41 [0.38, 0.44] | 1.67 [1.17, 2.18] | 1.87 [1.48, 2.25] | 0.81 | 0.47 |

| Temporal lobe | −154.2 | −182.7 | 28.5 | 5.70 [5.38, 6.02] | 0.32 [0.30, 0.34] | 0.33 [0.31, 0.35] | 3.12 [2.56, 3.67] | 1.73 [1.33, 2.14] | 0.85 | 0.64 |

| Parietal lobe | −168.7 | −180.3 | 11.5 | 4.51 [4.27, 4.75] | 0.4 [0.37, 0.43] | 0.4 [0.37, 0.43] | 2.03 [1.52, 2.54] | 1.65 [1.26, 2.03] | 0.82 | 0.55 |

| Frontal lobe | −163.1 | −183.4 | 20.3 | 4.85 [4.58, 5,12] | 0.37 [0.34, 0.40] | 0.38 [0.35, 0.41] | 2.55 [2.01, 3.10] | 1.49 [1.07, 1.91] | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | −149.6 | −170.7 | 21.0 | 7.08 [5.80, 8.36] | 0.26 [0.24, 0.28] | 0.27 [0.26, 0.28] | 3.92 [3.37, 4.48] | 1.57 [1.15, 1.98] | 0.78 | 0.71 |

| Cerebellum | −181.5 | −179.0 | −2.4 | 2.29 [2.15, 2.43] | 0.39 [0.36, 0.42] | 0.42 [0.39, 0.45] | 0.15 [−0.37, 0.67] | 1.36 [0.98, 1.74] | 0.66 | 0.10 |

| Accumbens | −127.5 | −165.1 | 37.6 | 11.05 [8.24, 13.86] | 0.42 [0.39, 0.45] | 0.41 [0.39, 0.43] | 6.58 [5.96, 7.21] | 1.63 [1.15, 2.11] | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| Hippocampus | −137.7 | −177.7 | 40.0 | 8.13 [6.46, 9.80] | 0.31 [0.30, 0.32] | 0.32 [0.30, 0.34] | 4.85 [4.29, 5.40] | 1.49 [1.05, 1.93] | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| Amygdala | −138.7 | −170.0 | 31.3 | 7.23 [6.45, 8.01] | 0.3 [0.28, 0.32] | 0.29 [0.27, 0.31] | 5.12 [4.55, 5.69] | 1.18 [0.72, 1.65] | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| Caudate | −155.2 | −175.7 | 20.5 | 3.47 [3.25, 3.69] | 0.38 [0.35, 0.41] | 0.37 [0.34, 0.40] | 2.06 [1.51, 2.62] | 0.63 [0.22, 1.04] | 0.31 | 0.77 |

| Putamen | −142.6 | −174.1 | 31.5 | 4.75 [4.31, 5.19] | 0.45 [0.42, 0.48] | 0.45 [0.43, 0.47] | 2.97 [2.44, 3.51] | 0.85 [0.44, 1.25] | 0.80 | 0.78 |

| Thalamus | −172.0 | −183.0 | 11.1 | 3.01 [2.76, 3.26] | 0.37 [0.35, 0.39] | 0.37 [0.35, 0.39] | 1.52 [1.01, 2.03] | 0.65 [0.27, 1.03] | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Midbrain | −178.6 | −180.3 | 1.6 | 1.63 [1.47, 1.79] | 0.3 [0.28, 0.32] | 0.32 [0.31, 0.33] | 0.47 [−0.05, 0.99] | 0.36 [−0.02, 0.74] | 0.51 | 0.57 |

| Medulla | −171.2 | −168.8 | −2.3 | 1.00 [0.92, 1.08] | 0.19 [0.16, 0.22] | 0.2 [0.18, 0.22] | 0.11 [−0.42, 0.65] | 0.07 [−0.33, 0.47] | 0.18 | 0.61 |

| Pons | −190.5 | −188.6 | −1.8 | 0.91 [0.83, 0.99] | 0.24 [0.23, 0.25] | 0.24 [0.22, 0.26] | 0.11 [−0.40, 0.63] | 0.01 [−0.38, 0.40] | 0.13 | 0.92 |

AIC: Akaike Information Criteria for model selection (smaller number indicates preferred model); VT: total distribution volume; K1: Delivery; : specific binding; : non-selective specific binding; : total specific binding.

Under the assumption that is accurate and invariant across regions, mean and CI were calculated equal to .

Figure 1.

Representative regional [11C]Ro15-4513 time-activity curves (•) and two TCM fits (-) from a decay-corrected tracer alone scan for four regions of interest (hippocampus, temporal lobe, frontal lobe and cerebellum).

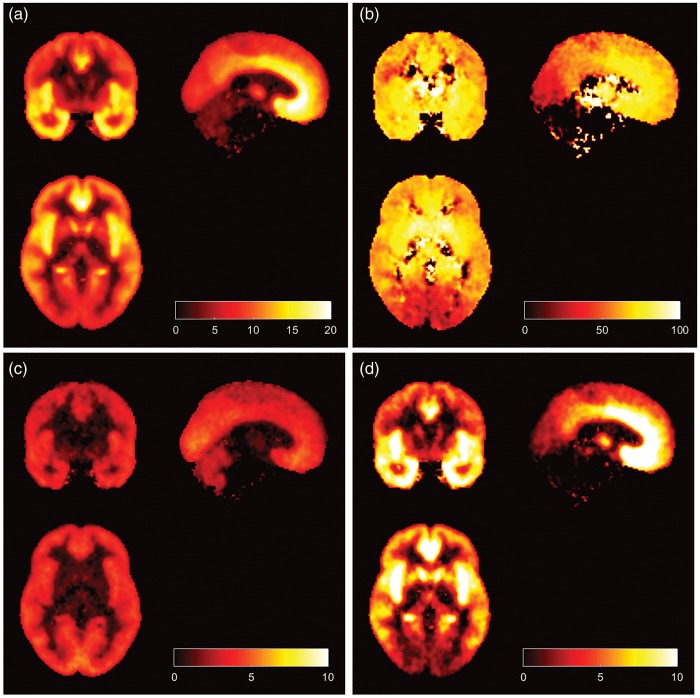

A competition binding model accounting for the selective modulator Basmisanil was fitted to all 18 ROIs. Examples of model fits from four representative regions are given in Figure 2. In each case, a good fit was obtained along with a corresponding estimate of in each region (see Table 1). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for each parameter estimate in each region are calculated and shown in Table 1. There was no evidence of any significant displaceable GABAAα5 signal in either the cerebellum or pons, whereas the other regions showed a clear dose dependent reduction in VT with increasing doses of Basmisanil.

Figure 2.

Heterologous competition between [11C]Ro15-4513 and the GABAAα5 selective negative allosteric modulator Basmisanil (RG1162) in four regions of interest. (a) Cerebellum, (b) frontal lobe, (c) temporal lobe and (d) hippocampus. VT values from the 27 [11C]Ro15-4513 scans are plotted against the Basmisanil plasma concentration (•) along with model fits from the competition binding model given in equation (2) (-).

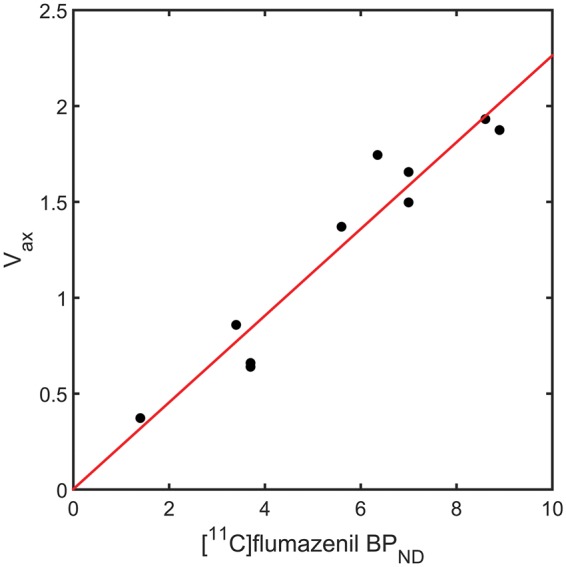

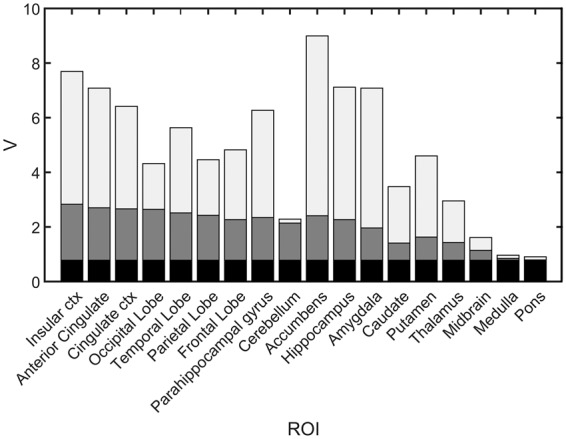

Optimisation of using the regional [11C]flumazenil data revealed a maximal agreement between , and [11C]flumazenil when = 0.78. A strong linear relationship was observed (R2 = 0.93), which supports the fact that the non-selective specific signal of [11C]Ro15-4513 is similar to the total specific signal from [11C]flumazenil (see Figure 3). Using this estimate of in conjunction with the regional estimates of and , it was then possible to calculate the regional selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 (see Figure 4, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Optimisation of using regional [11C]flumazenil and [11C]Ro15-4513 () for 10 ROIs (cerebellum, frontal lobe, cingulate cortex, parietal lobe, thalamus, parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cingulate and caudate). , , with .

Figure 4.

Regional in vivo selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 in humans. The partitioning of the total volume of distribution into non-displaceable (black), non-selective specific binding (dark grey) and GABAAα5 selective specific binding (light grey) are shown for 18 ROIs.

Parametric images of [11C]Ro15-4513 VT along with the specific and volumes of distribution are displayed in Figure 5. Consistent with preclinical data on GABAAα5, highest VT is seen in subcortical limbic structures including the nucleus accumbens and hippocampus, as well as the anterior cingulate and insula. Low signal is seen in the striatum, cerebellum and brainstem. The images confirm this distribution, and maps of are similar to VT images obtained with [11C]flumazenil. Images of the percentage specific signal attributable to demonstrate the high GABAAα5 subcortical signal, decreasing into the cortex and lowest in the occipital cortex, cerebellum and brainstem.

Figure 5.

Parametric images of [11C]Ro15-4513 in humans: (a) Total distribution volume (VT), (b) Percentage of specific binding which is , (c) specific binding and (d) specific binding .

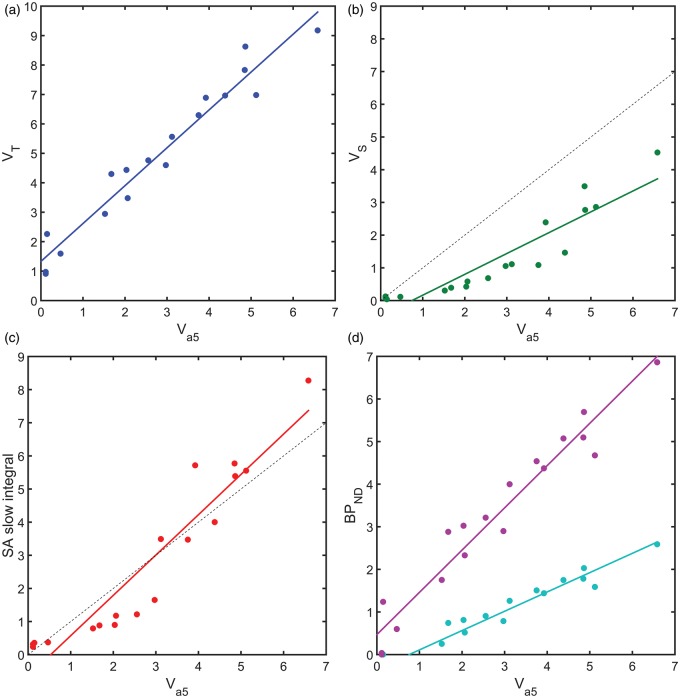

The results from the heterologous competition data then allowed for an assessment of the performance of four different analysis approaches that have been previously applied to [11C]Ro15-4513, in the absence of competition data, to estimate GABAAα5 binding. The four approaches considered involved the two tissue compartment model, spectral analysis and the simplified reference tissue model (see Figure 6). Total VT estimates from the 2TCM provided a good linear relationship with (Method I: 2TCM VT = 1.29 + 1.33, R2 = 0.95), consistent with the expected constant offset due to the term. Estimation of VS from the 2TCM demonstrated a non-linear relationship with increased variance, y-axis offset and a significant deviation from a slope of unity (Method II: 2TCM VS = 0.64 – 0.47, R2 = 0.85). The bandpass spectral analysis method provided a non-linear relationship to similar to Method II, although with a slope closer to unity (Method III: SA VS = 1.22 - 0.64, R2 =0.89). Finally, SRTM gave a good linear relationship with either the cerebellum or pons as a reference tissue, between and , with a y-axis offset (Method IV: SRTM (cerebellum) = 0.45 + 0.34, R2 = 0.95; SRTM (pons) = 0.99 + 0.47, R2 = 0.94).

Figure 6.

Performance of four analysis methods for the estimation of GABAAα5 binding with [11C]Ro15-4513. Model outcome measures plotted against the gold standard estimates determined from the heterologous competition data; (a) Method I (2TCM VT), (b) Method II (2TCM VS), (c) Method III (SA ) and (d) Method IV (SRTM : Pons Reference Tissue (magenta) and Cerebellum reference Tissue (cyan)). In the cases of (b) and (c), a dotted line representing unity is also shown.

Discussion

A full characterisation of [11C]Ro15-4513 in humans using heterologous competition data has been presented that allows for the determination of the GABAAα5 specific binding signal, as well as an estimate of the remaining GABAA sub-type specific binding and non-displaceable signal across the brain. This provides important information to help with the interpretation of previous clinical studies employing [11C]Ro15-4513 PET in humans. Further, it provides gold standard data that permits the evaluation of alternative analysis strategies for [11C]Ro15-4513.

The human [11C]Ro15-4513 PET data used in our analysis included scans performed at baseline and following the administration of an α5-selective negative allosteric modulator (RG1662). Using competition data obtained across a range of different doses allowed us to isolate the specific binding component of the total volume of distribution that corresponds to GABAAα5 by applying an appropriate competition binding model. The remaining portion of the VT was partitioned into the non-displaceable and remaining GABAA subtype binding using [11C]flumazenil data obtained from the literature.

Our approach allowed careful validation of different approaches for quantification of GABAAα5 density, not possible before. Given that most studies using this radioligand will be undertaken in the absence of competitive blockade, it is important to understand the regional selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 and the limitations of different analysis approaches that attempt to quantify GABAAα5 binding.

The 2TCM was identified as the optimal tracer kinetic model to describe the kinetics of [11C]Ro15-4513 based on the Akaike information criteria. This is consistent with previous model identification analyses performed for this tracer.6,9,28 VT was greatest in the nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate gyrus and amygdala, regions also found to have the greatest proportions of α5-specific signal contribution. Regions with relatively low α5-specific binding were found to be equally well fitted using a 1TCM model. Subcortical regions, such as the striatum, including the putamen and caudate nuclei, despite their relatively low total VT, display a relatively greater proportion of α5-specific signal as compared with the cortical structures. This proportion of α5-specific signal demonstrates good, but not complete, selectivity for the subtype, with an average of 66% of the specific signal across all measured regions, including low-signal regions such as the cerebellum.

Comparing the different analysis methods against the gold standard GABAAα5 data in this cohort of healthy human subjects showed that VT derived from 2TCM has a good linear relationship with GABAAα5 specific binding, consistent with GABAAα5 representing a significant portion of the specific binding in most regions considered although its use requires interpreting an outcome measure that contains a degree of non-selective binding. While inferences may be made regionally, there will not be any absolute certainty of the source of any change or difference in signal, from GABAAα5 or any other subtype.

VS, derived from the 2TCM, has a non-linear relationship with , and a higher variance, with regions of lower signal underestimated and those of higher signal overestimated. Thus, whilst trying to more accurately quantify the exact level of GABAAα5 specific binding, this method ends up having significant bias and variance. This is not unexpected given the challenge of having to both try to kinetically partition the data and rely on the interpretation that the second tissue compartment contains only α5 specific binding. Even for radioligands that bind selectively to only one target, it has been shown previously that the direct estimation of these parameters is challenging and the most robust use of this type of method involves subtracting the obtained from a reference region off the VT to obtain VS instead.29

The derived from bandpass spectral analysis relies on being able to separate the component corresponding to the specific α5 signal purely from the kinetics. This is inherently very difficult because there are components due to free and non-specific binding in addition to the α5 and non-α5 specific components. Thus, even if one is able to separate the two specific components, it is not clear how the non-displaceable component is attributed. Further, the kinetic partitioning of PET data is easily influenced by noise, subject motion, and inaccuracies in corrections such as scatter. Thus, it is very challenging to try and estimate the specific α5 component this way and therefore it is not surprising that the SA method suffers from inaccuracies. This is analogous to the challenges of directly estimating the from direct estimates of k3 over k4 in the 2TCM where again kinetic partitioning is required.29 The performance of both these methods is further evidence that kinetic partitioning methods are not the primary methods of choice.

Finally, the application of SRTM using the cerebellum or pons provides a linear relationship with the true GABAAα5 binding. For cortical regions, the cerebellum reference region with its increased statistics from a larger region and similar levels of off target non-selective binding may be most appropriate. In particular, given that without a homologous competition study, it has been necessary to make the assumption that is equal across all regions, for occupancy studies, it makes most sense to use a cerebellum reference region and cortical estimates of occupancy, as they are not dependent on this assumption. The use of a cerebellum reference to quantify sub-cortical structures is more questionable with differing levels of off target binding present. In this context, it should be noted that the non-displaceable denominator in also contains the off target specific binding term and should also be accounted for in the use of this parameter. Thus, if changes across subjects or between interventions, it will cause problems for the interpretation of this parameter. In contrast, the pons, a smaller and noisier region, whilst being devoid of specific binding is likely to suffer from high variance in estimates.

Overall, each of the four quantification approaches has their strengths and weaknesses. The overall estimations of VT and from the 2TCM and SRTM, respectively, lead to good numerical identifiability of these parameters, principally because they are macro-parameters,26 uniquely defined from the models’ impulse response functions and reasonably robust in the presence of noise. The shortcomings of these two approaches are that the outcome measures by design contain a component of the off target binding. Nevertheless, if the off-target binding can be assumed to be unchanged across populations or between interventions, then these are the methods of choice. In contrast, the estimation of VS and from the 2TCM and spectral analysis rely on the kinetic partitioning of the data through the estimation of microparameters, which leads to the increased problems of numerical identifiability with these outcome measures. Further, they also rely on the interpretation, in the 2TCM case that the second compartment corresponds only to α5 signal and in the case of spectral analysis that all the α5 signal can be kinetically partitioned at one end of the spectrum. Both methods will struggle more with heterogeneity and noise than the macroparameter based methods (Methods I and IV). The strength of Methods II and III is that they try to estimate only the α5 signal.

Thus, the choice of method used in a clinical [11C]Ro15-4513 study should be considered carefully. The ideal situation would be to perform two scans, one with the tracer alone and the second in the presence of a blocking dose of a selective GABAAα5 drug such as Basmisanil; however, this is unlikely to be feasible routinely. If a single scan approach is employed with arterial blood data and one of the more exploratory methods (II and III) is used, then the VT from Method I should also always be presented. This would allow for a consensus analysis to determine whether all the results are consistent. If blood is not acquired and SRTM is used, then one should understand that the interpretation of the outcome measure would rely strongly on the credibility of the assumptions about the off target binding in the particular experimental paradigm under investigation.

In conclusion, we have fully characterised the in vivo selectivity of [11C]Ro15-4513 in humans using heterologous competition data. Overall, the tracer provides a good deal of selectivity for GABAAα5, with α5 representing at least 60–70% of the specific binding in most regions. Nevertheless, the presence of off-target non-selective binding to other GABAA subtypes means that the choice of analysis method and the interpretation of outcome measures must be considered carefully in the context of the experimental design of each [11C]Ro15-4513 clinical PET study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Our post hoc analyses makes use of a subset of data obtained from a research study commissioned by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, performed by Hammersmith Imanet (a division of GE Healthcare) and Hammersmith Medicines Research in 2010. The authors would like to thank the staff of both organisations (including Kerstin Heurling, Lisa Desmond, Alan Forster and David J Brooks) for their role in the design of the study and data acquisition. The authors would also like to thank Sian Lennon-Chrimes, Xavier Liogier d'Ardhuy, Stephane Nave, Darshna Shah, Andrew Thomas and Nicholas Seneca from F. Hoffmann-La Roche for their work on the design and contact of that study. Finally, we would also like to thank Ilan Rabiner for discussions around this project, and Dr Edilio Borroni for his support.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: RG is a consultant for Abbvie, GlaxoSmithKline and UCB. JM received a travel grant from F Hoffmann-La Roche for the presentation of this work at a scientific meeting. RC is an employee of F Hoffmann-La Roche.

Authors’ contributions

JM contributed to analysis of data and drafted the article. RC contributed to interpretation of the data and revised the article. RG contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the article. All authors approved the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at http://jcbfm.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- 1.Pike VW, Halldin C, Crouzel C, et al. Radioligands for PET studies of central benzodiazepine receptors and PK (peripheral benzodiazepine) binding sites–current status. Nucl Med Biol 1993; 20: 503–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards JG, Mohler H, Schoch P, et al. The visualization of neuronal benzodiazepine receptors in the brain by autoradiography and immunohistochemistry. J Recept Res 1984; 4: 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battaglioli G, Martin DL. GABA synthesis in brain slices is dependent on glutamine produced in astrocytes. Neurochem Res 1991; 16: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonetti EP, Burkard WP, Gabl M, et al. Ro 15-4513: partial inverse agonism at the BZR and interaction with ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1988; 31: 733–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers JF, Stokes PRA, Kalk NJ, et al. Sensitivity of the benzodiazepine inverse agonist PET ligand [C-11] Ro15-4513 to changes in endogenous GABA. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32(S1): P069. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers JF, Rosso L, Watson BJ, et al. Characterisation of the contribution of the GABA-benzodiazepine alpha1 receptor subtype to [(11)C]Ro15-4513 PET images. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadingham KL, Wingrove P, Le BB, et al. Cloning of cDNA sequences encoding human alpha 2 and alpha 3 gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subunits and characterization of the benzodiazepine pharmacology of recombinant alpha 1-, alpha 2-, alpha 3-, and alpha 5-containing human gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Mol Pharmacol 1993; 43: 970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieghart W. Structure and pharmacology of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Rev 1995; 47: 181–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingford-Hughes A, Hume SP, Feeney A, et al. Imaging the GABA-benzodiazepine receptor subtype containing the alpha5-subunit in vivo with [11C]Ro15 4513 positron emission tomography. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2002; 22: 878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner DM, Sapp DW, Olsen RW. The benzodiazepine/alcohol antagonist Ro 15-4513: binding to a GABAA receptor subtype that is insensitive to diazepam. J Pharmacol Exp Therap 1991; 257: 1236–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halldin C, Farde L, Litton JE, et al. [11C]Ro 15-4513, a ligand for visualization of benzodiazepine receptor binding. Preparation, autoradiography and positron emission tomography. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992; 108: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall H, Litton JE, Halldin C, et al. Studies on the binding of [H-3] flumazenil and [H-3] sarmazenil in postmortem human brain. Hum Psychopharm Clin 1992; 7: R2–R2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol 1995; 359: 154–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda J, Suhara T, Kawabe K, et al. Visualization of alpha5 subunit of GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor by 11C Ro15-4513 using positron emission tomography. Synapse 2003; 47: 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue O, Suhara T, Itoh T, et al. In vivo binding of [11C]Ro15-4513 in human brain measured with PET. Neurosci Lett 1992; 145: 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asai Y, Ikoma Y, Takano A, et al. Quantitative analyses of [11C]Ro15-4513 binding to subunits of GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor in the living human brain. Nucl Med Commun 2009; 11: 872–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litton JE, Hall H, Pauli S. Saturation analysis in PET–analysis of errors due to imperfect reference regions. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 1994; 14: 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klumpers UM, Veltman DJ, Boellaard R, et al. Comparison of plasma input and reference tissue models for analysing [(11)C]flumazenil studies. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salmi E, Aalto S, Hirvonen J, et al. Measurement of GABAA receptor binding in vivo with [11C]flumazenil: a test-retest study in healthy subjects. NeuroImage 2008; 41: 260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammers A, Panagoda P, Heckemann RA, et al. [11C]Flumazenil PET in temporal lobe epilepsy: do we need an arterial input function or kinetic modeling? J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas et al., in preparation.

- 22.Hernandez et al., in preparation.

- 23.Searle G, Gunn R. Molecular imaging and kinetic analysis toolbox (MIAKAT). J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2013; 57: 679–670. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tziortzi et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: Dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. NeuroImage 2011; 54(1): 264–277. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lassen NA, Bartenstein PA, Lammertsma AA, et al. Benzodiazepine receptor quantification in vivo in humans using [11C]flumazenil and PET: application of the steady-state principle. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 1995; 15: 152–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunn RN, Gunn SR, Cunningham VJ. Positron emission tomography compartmental models. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2001; 21: 635–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham VJ, Jones T. Spectral analysis of dynamic PET studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1993; 13: 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barros DAR, Heckemann RA, Rosso L, et al. Investigating the reproducibility of the novel alpha-5 GABAA receptor PET ligand [11C]Ro15 4513. NeuroImage 2010; 52(Supplement 1): S112. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 1996; 4(3 Pt 1): 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunn RN, Lammertsma AA, Hume SP, et al. Parametric imaging of ligand-receptor binding in PET using a simplified reference region model. Neuroimage 1997; 6: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingford-Hughes A, Reid AG, Myers J, et al. A [11c] Ro15 4513 PET study suggests that alcohol dependence in man is associated with reduced α5 benzodiazepine receptors in limbic regions. J Psychopharmacol 2012; 26: 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Searle G, Coello C, Gunn R. Realising the binding potential directly and indirectly. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2015; 64: 19–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.