Abstract

The ability of the parasympathetic nervous system to flexibly adapt to changes in environmental context is thought to serve as a physiological indicator of self-regulatory capacity, and deficits in parasympathetic flexibility appear to characterize affective disorders such as depression. However, whether parasympathetic flexibility (vagal withdrawal to emotional or environmental challenges such as sadness, and vagal augmentation during recovery from sadness) could facilitate the effectiveness of adaptive affect regulation strategies is not known. In the present study of 178 undergraduate students, we evaluated whether parasympathetic flexibility in response to a sad film involving loss would enhance the effectiveness of regulatory strategies (reappraisal, distraction, and suppression) spontaneously employed to reduce negative affect during a two-minute uninstructed recovery period following the induction. Parasympathetic reactivity and recovery were indexed by fluctuations in respiratory sinus arrhythmia and high-frequency heart rate variability. Cognitive reappraisal and distraction were more effective in attenuating negative affect among individuals with more parasympathetic flexibility, particularly greater vagal augmentation during recovery, relative to individuals with less parasympathetic flexibility. In contrast, suppression was associated with less attenuation of negative affect, but only among individuals who also had less vagal withdrawal during the sad film. Alternative models provided partial support for reversed directionality, with reappraisal predicting greater parasympathetic recovery, but only when individuals also experienced greater reductions in negative affect. These results suggest that contextually appropriate parasympathetic reactivity and recovery may facilitate the success of affect regulation. Impairments in parasympathetic flexibility could confer risk for affective disorders due to attenuated capacity for effective self-regulation.

Sadness is thought to be a normative and evolutionarily adaptive response to loss (Beck & Bredemeier, 2016; Hammen, 2005). However, the ability to effectively regulate or attenuate negative affect (NA) following loss is important, as persistent NA can lead to various forms of psychopathology such as depression (Kovacs et al., 2016; Woody & Gibb, 2015). Over the past few decades, several strategies for the regulation of NA have been identified, some of which are considered maladaptive (e.g., suppression), and others adaptive (e.g., reappraisal, distraction) at reducing NA (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010; Gross, 2013). However, all adaptive regulatory strategies are not necessarily equally effective across individuals. For example, depression appears to be characterized by an inability to effectively regulate sadness, even when “adaptive” strategies are implemented (Gross, 2013; Joormann & Vanderlind, 2014). Thus, researchers have called for studies to evaluate behavioral and physiological predictors of the degree to which adaptive strategies are effective at reducing NA (e.g., Joormann & D’Avanzato, 2010; Pe et al., 2013), and an improved understanding of the contexts in which “maladaptive” strategies are less harmful or actually helpful in improving affect (Aldao, 2013; Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004; Westphal, Seivert, & Bonanno, 2010).

Two commonly studied adaptive regulatory strategies are cognitive reappraisal, which involves reinterpreting the meaning of the emotional stimulus, and distraction, which is characterized as redirecting attention to other stimuli (Aldao et al., 2010; Gross, 2013). Both strategies are considered to be adaptive because they are associated with the successful downregulation of NA and they are negatively associated with psychopathology (Aldao et al., 2010; Kovacs et al., 2015; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Webb, Miles, & Sheeran, 2012). In contrast, expressive suppression involves masking one’s emotional expression so that it is unnoticeable to others, with effects that generally are considered maladaptive (Aldao et al., 2010; Gross, 2013; but see Bonanno et al., 2004). Identifying characteristics associated with ineffective attempts to regulate will be important in understanding the degree to which putatively adaptive strategies are universally useful when implemented (Aldao, 2013; Bonanno & Burton, 2013). In addition, identifying possible physiological mechanisms that might underlie effective or ineffective affect regulation could improve understanding of possible phenotypic risk factors for emotion dysregulation and mood disorders (Hofmann et al., 2012). Given that a primary goal of many psychosocial interventions is to increase the use of adaptive regulatory responses, it is important to identify contextual factors, such as physiological states, that may facilitate or interfere with the effectiveness of these responses (e.g., Yaroslavsky et al., 2013). This work is particularly timely given that emerging biofeedback approaches may be beneficial for improving the effectiveness of regulatory responses (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Nolan et al., 2005; Valenza et al., 2014).

One candidate physiological process that could facilitate effective self-regulation is cardiac vagal control (CVC), which is thought to predominantly represent parasympathetic nervous system activity (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Rottenberg, 2007a; Thayer et al., 2012). Several theories and models, including Porges’s (2007) polyvagal theory and the neurovisceral integration model (Thayer & Lane, 2000), provide neural and anatomic justification for the role of CVC in self-regulation. Specifically, during periods of rest, the medial prefrontal cortex exerts inhibitory control over the amygdala, indirectly enhancing cardiac control via the vagus nerve, and resulting in low heart rate and elevated CVC (Thayer et al., 2012). However, during periods of emotional or environmental challenge, the parasympathetic nervous system typically withdraws its inhibitory control over heart rate, which reduces vagal control, thereby allowing the body to mobilize resources needed to flexibly respond and adapt to the challenge (Beauchaine, 2001). This withdrawal of parasympathetic activity is thought to represent a contextually-appropriate engagement of attention with salient stimuli. When the challenge remits, inhibitory vagal control typically is augmented and CVC returns to resting levels (Rottenberg, 2007a), potentially representing a conservation of autonomic resources once the perceived challenge has remitted.

CVC can be indexed by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), a measure of variability in heart rate that occurs over the respiration cycle, and by heart rate variability (HRV) that occurs within the high-frequency range that is most strongly associated with respiration (Allen et al., 2007; Berntson et al., 1997; Rottenberg, 2007a). Although the measurement of HRV differs from RSA in that it does not require respiration to be measured, these indices typically are highly correlated within individuals and are thought to similarly index CVC (Allen et al., 2007; Grossman et al., 1990). Although HRV and RSA are often discussed interchangeably in the literature as imperfect measures of CVC, few studies have examined both of these measures in relation to regulatory effectiveness, which may elucidate the specificity (or similarity) of these indices in predicting affect-related processes. Importantly, evaluating adaptive fluctuations in CVC in response to sadness (e.g., reductions in RSA and HRV in response to sadness, and augmentation of RSA and HRV during recovery from sadness) may provide useful information about the capacity for flexible adaptation of affective responses to meet contextual demands (hereafter called “parasympathetic flexibility”) (Beauchaine, 2001; Gentzler et al., 2009; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Kreibig, 2010; Porges, 2007; Rottenberg, 2007a; Thayer & Lane, 2009; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013; Stange et al., in press). A growing body of work has suggested that parasympathetic flexibility, including both attenuated vagal withdrawal to sad films and blunted vagal augmentation during recovery from sad films, is impaired among individuals with depressive disorders (e.g., Bylsma et al., 2014; Rottenberg, 2007a; Rottenberg et al., 2005, 2007a; Panaite et al., 2016) and may index an endophenotype for depression (Yaroslavsky et al., 2014).

Given the presence of shared neural pathways, parasympathetic flexibility has been proposed as a biological index of the capacity for effective emotion regulation (Beauchaine & Thayer, 2015; Thayer et al., 2012). Studies of resting HRV have demonstrated positive associations with adaptive cognitive responses to NA (Beevers et al., 2011; Volokhov & Demaree, 2010) and improved downregulation of arousal in the context of stress (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1997; Hildebrandt et al., 2016). RSA withdrawal to sad stimuli also has been associated with the use of distraction in response to sadness (LeMoult et al., 2016), lower levels of maladaptive regulatory strategies (Kovacs et al., 2016; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013, 2016), and with improved affect regulation abilities across adolescence (Vasilev et al., 2009).

Although parasympathetic flexibility seems to be implicated in affect regulation (Beauchaine & Thayer, 2015), few studies have evaluated how flexible parasympathetic responses to sadness (i.e., RSA and HRV withdrawal) and recovery from sadness (i.e., RSA and HRV augmentation) might modulate the effectiveness of adaptive affect regulation strategies. It is plausible that parasympathetic flexibility facilitates the effective use of regulatory strategies by allowing for greater physiological capacity for affective recovery, whereas inflexible parasympathetic responses might interfere with affective recovery (e.g., Yaroslavsky et al., 2013). Although no studies to our knowledge have evaluated these questions with respect to the spontaneous use of regulatory strategies for sadness, a few existing studies may provide some clues. For instance, one study found that adaptive patterns of RSA in response to a sad film were associated with more effective trait mood repair, and with more effective implementation of instructed mood repair strategies in the lab (Yaroslavsky et al., 2016). Another study demonstrated that poorer vagal recovery from an emotional challenge was associated with more NA (and hence, less effective regulation) during a delay task among children (Santucci et al., 2008). Moreover, among bereaved individuals, a written emotional disclosure intervention was more likely to decrease depressive symptoms (relative to a control group) among participants who had higher resting RSA (O’Connor et al., 2005); a similar study replicated these effects on depressive symptoms and physical health outcomes among college students (Sloan & Epstein, 2005). Although useful for experimental control, studies of affect regulation such as these that instruct individuals to implement specific strategies may have limited ecological validity compared to paradigms that assess strategies that individuals implement spontaneously (i.e., without instruction; e.g., Aldao, 2013; Berkman & Lieberman, 2009; Egloff et al., 2006; Ehring et al., 2010; Gruber et al., 2012). However, no studies to our knowledge have directly evaluated the extent to which components of parasympathetic flexibility may enhance the uninstructed downregulation of NA.

In the present study, we evaluated whether parasympathetic flexibility in response to a sad film in the lab would enhance the association between the spontaneous implementation of adaptive affect regulation strategies (reappraisal and distraction) and decreases in NA during an uninstructed recovery period. We hypothesized that individuals who demonstrated greater parasympathetic withdrawal to the sad film or greater parasympathetic augmentation following the sad film (i.e., parasympathetic flexibility) would report greater effectiveness of adaptive regulatory strategies (greater decreases in NA during recovery) than would individuals who demonstrated less flexible parasympathetic responses. In contrast, we hypothesized that suppression would be associated with increases in NA, but that this effect would be attenuated among individuals with greater parasympathetic flexibility.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate students at Temple University aged 18 to 50. The majority of participants (97%) were young adults (ages 18–39; 43% male), whereas a smaller number (3%) were middle-aged (ages 40–50; 33% male). Participants were required to be fluent in English, have normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and to be free of cardiac conditions. Participants were recruited from undergraduate psychology classes using the department’s online listing of studies, and from the diverse student body via flyers posted around campus. They received psychology course credit and/or were compensated in cash for participation. All participants completed informed consent approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

The sample included 178 participants (Mage = 21.95, SD = 5.71) who viewed the sad film and completed questionnaires while connected to the physiological equipment. As the present study design was relatively novel, few estimates of expected effect size were available; however, based on the extant literature (e.g., Egloff et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2012; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013), we estimated that effect sizes of relationships between spontaneous regulatory strategies and changes in affect would be medium, with medium-to-large differences in this relationship expected between groups of high and low parasympathetic flexibility. A priori power analyses conducted in G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) for two-tailed linear regressions comparing differences between slopes (i.e., interaction effects) with Power = .80 and α = .05 suggested a total sample size of 160 would be needed; thus, we anticipated that the present sample of 178 would be sufficient. The final sample was 57.3% female, 9.0% Hispanic or Latino, 20.2% African American/Black, 64.6% Caucasian/White, 11.8% Asian, 0.6% Pacific Islander, 1.1% Native American, and 6.7% “other” race.

Measures

Parasympathetic Flexibility

Participants were seated comfortably in a small assessment room where the experimenter attached cardiovascular sensors. After a five-minute rest period to become acclimated to the room and sensors, participants watched a series of video clips, which were presented on a desktop computer approximately 24 inches in front of them. Film selection was based on criteria recommended by Rottenberg et al. (2007b). To establish physiological parameters during a neutral baseline film, participants first viewed a two-minute nature film clip (a documentary on Denali National Park), followed by a film depicting a boy who is distraught at the death of his father (the movie The Champ, two minutes and fifty-one seconds long), which has been demonstrated to elicit sadness (Rottenberg et al., 2007b). Previous work indicates that vagal recovery is most likely to occur during an unchallenged period immediately following emotional challenges (e.g., 60–120 seconds following the challenge; Rottenberg et al., 2003, 2007a; Mezzacappa et al., 2001). Thus, participants then completed a two-minute recovery period of rest in which they were asked to sit quietly. Participants completed a brief set of questions immediately following each experimental period (described below).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and respiration signals were assessed with a three-lead electrocardiogram and BioPac BioHarness, and were continuously recorded on a PC with AcqKnowledge 4.3 (equipment and software from Biopac Instruments Inc., Goleta, CA), sampled at 1000Hz. Cloth base disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes were placed in a modified Lead-II configuration on the chest. ECG signals were amplified with a BioPac ECG100 amplifier. We measured respiration rate with an RSP100C amplifier with a TSD100C respiratory transducer, which was placed around the chest, crossing under the armpits and on top of the breastbone. Respiration data were high-pass filtered and visually inspected for artifacts and corrected when needed, following well-established procedures outlined elsewhere (Grossman et al., 1990; Rottenberg et al., 2007a). HR data were visually inspected for artifacts, which were manually adjusted as necessary (< 1% of heartbeats required adjustment).

RSA was calculated within AcqKnowledge using the well-validated peak-valley method (Grossman et al., 1990). The maximum heart rate during the expiration window of respiration was subtracted from the minimum heart rate during the inspiration window of respiration. RSA was computed in milliseconds such that higher values reflected greater vagal tone (or parasympathetic activity). High-frequency HRV was computed within AcqKnowledge using the frequency domain method of power spectral analysis, as recommended by the Task Force (1996). Tachograms were created with a QRS detector using a modified Pan and Tompkins algorithm (Pan & Tompkins, 1985). R-R intervals were re-sampled with a cubic-spline interpolation at a resampling frequency of 8 Hz to generate continuous time-domain representations of the R-R intervals. Total power in the high-frequency range (0.15–0.4 Hz) was computed for each epoch and recorded in milliseconds squared. As is typical, given its skewed distribution, a natural-log transformation normalized these data.

Average RSA, HR, and respiration rate were computed separately for each experimental period (neutral film #1, sad film, and recovery period). To compute the measures of parasympathetic flexibility of primary interest in the present study, we computed two types of difference scores representing change in RSA and HRV between periods: neutral film #1 and sad film (RSA and HRV reactivity to the sad film, with higher scores representing greater vagal withdrawal to the sad film relative to the neutral film), and sad film and recovery period (RSA and HRV recovery from the sad film, with higher scores representing greater vagal augmentation during the recovery period relative to the sad film) (Rottenberg et al., 2005). Given that RSA, HR, and respiration typically are correlated (e.g., Overbeek et al., 2012), to rule out possible confounds, analyses included heart rate and respiration rate during the relevant periods as covariates (e.g., Berntson et al., 1997; Meissner et al., 2011).

Spontaneous Affect Regulation Scale (SARS) (Egloff et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2012)

The SARS is a set of questions based on the format of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) that was used to assess the degree to which participants spontaneously (i.e., without instruction) employed regulation strategies, including reappraisal, distraction, and suppression, during the period following the sad film. After the recovery period, participants were asked to rate the degree to which several statements were true of them during the period following the sad film. Distraction was evaluated with three statements, which were drawn from questions on the original response styles questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999): (1) Think “I’m not going to think about how I feel”; (2) Think “I’ll concentrate on something other than how I feel”; (3) Do something to distract yourself. Reappraisal was evaluated with three questions from the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003; Egloff et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2012): (1) Remind yourself that these feelings won’t last; (2) Changed the way I was thinking to feel less negative emotion; (3) Changed the way I was thinking to feel more positive emotion. Suppression was evaluated with three questions from the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003; Egloff et al., 2006): (1) I controlled my emotions; (2) I was careful not to express negative emotions; (3) One could see my feelings (reverse-scored). Higher scores on either subscale represent a greater degree of implementation of that strategy. The SARS was administered at the end of the two-minute recovery period following the sad film, consistent with prior studies that have used the measure following periods after emotion inductions (Egloff et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2012). The SARS subscales showed adequate internal consistency in prior studies (Egloff et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2012) as well as in the current study (Reappraisal α = .70, Distraction α = .73, Suppression α = .68).

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) – Brief Version (Mackinnon et al., 1999)

The PANAS – Brief version is a 10-item version of the original self-report measure (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) that assesses current emotions and affective experiences. The PANAS is a commonly-used measure of affect in experimental studies, and it has excellent validity and reliability (Watson et al., 1988). For each word, participants were asked to “indicate to what extent you feel this way right now, that is, at the present moment,” on a scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 4 (extremely). It contains two subscales, each with five items, which are computed by summing the items for a maximum score of 20: positive affect (inspired, alert, excited, enthusiastic, determined) and negative affect (afraid, upset, nervous, scared, distressed). The present study focused on the negative affect (NA) subscale given its importance in loss events and in emotional disorders, but also evaluated the positive affect (PA) subscale as an outcome of secondary interest. The PANAS was administered before and after each of the film and rest periods in the study to evaluate shifts in affect. A difference score was computed by subtracting the post-recovery NA score from the post-sad-film NA score to assess changes in negative affect during the recovery period, with higher scores representing greater reductions (more improvement) in NA; a comparable difference score was created for PA by subtracting post-sad-film PA from post-recovery PA so that higher scores represented greater increases (more improvement) in PA. In the present study, the NA and PA subscales had excellent internal consistency across the experimental periods (NA α = .90–.97; PA α = .90–.94).

Data Analysis

Linear regressions were used to evaluate whether parasympathetic flexibility (greater reactivity of RSA and HRV in response to the sad film, and greater recovery of RSA and HRV during the recovery period following the sad film) would moderate the extent to which reappraisal, distraction, and suppression would predict decreases in NA (and increases in PA) following the recovery period. Each analysis included the main effect of reappraisal, distraction, or suppression, the main effect of the given index of parasympathetic flexibility (RSA or HRV reactivity, RSA or HRV recovery), the interaction term, and baseline levels of RSA or HRV within the given analysis as a covariate (e.g., controlling for RSA during the neutral film when examining RSA reactivity to the sad film as a moderator). Simple slopes of significant interaction terms were probed at +/− 1 standard deviation from the mean of the moderator variable (parasympathetic flexibility) (Aiken & West, 1991). Variables were standardized prior to analysis. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to examine whether results changed when accounting for additional covariates, including sex, age, race, body mass index, and the use of antidepressants and other psychiatric medications (Kemp et al., 2010).

Given the cross-sectional nature of the data and the overlap in the periods during which parasympathetic and affective recovery were evaluated, we examined an alternative set of hypotheses that affect recovery would facilitate parasympathetic recovery when individuals engaged in adaptive regulatory strategies. Each analysis included the main effect of reappraisal, distraction, or suppression, the main effect of recovery of affect, the interaction term, and baseline levels of NA as a covariate, predicting degree of HRV recovery or RSA recovery.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

First, we conducted manipulation checks to evaluate the extent to which affect fluctuated across experimental periods. As expected, compared to the first neutral baseline film, there was an increase in NA (t = −9.66, p < .0001, d = .53)1 and a decrease in PA (t = 10.36, p < .0001, d = .53) following the sad film. Compared to the end of the sad film, following the recovery period, there was a significant decrease in NA (t = 8.36, p < .0001, d = .36) and an increase in PA (t = −4.55, p < .0001, d = .22).

Given that prior work has suggested that participants typically experience modest changes in parasympathetic activity across emotional contexts, and that these differences are variable across individuals (Kovacs et al., 2016; Overbeek et al., 2012; Panaite et al., 2016; Rottenberg, 2007a; Rottenberg et al., 2005, 2007), we were more interested in individual differences in parasympathetic indices than in absolute changes across the sample. However, we also explored the extent to which participants overall experienced fluctuations in parasympathetic activity during the sad film and recovery period. Following the sad film, participants experienced decreases in RSA (t = 4.52, p < .0001, d = .19) and HRV (t = 4.58, p < .0001, d = .14). During the recovery period, participants experienced marginally significant augmentation of RSA (t = −1.87, p = .06, d = .08) but not in HRV (t = −0.68, p = .50, d = .03). Descriptive statistics for NA, RSA, and HRV within each experimental period are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia, High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability, and Negative Affect Across Each Period.

| RSA | HRV | NA | PA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Neutral Film | 102.68 | 58.69 | 2.57 | 1.11 | 6.70 | 4.01 | 13.27 | 5.22 |

| Sad Film | 92.28 | 48.24 | 2.42 | 1.09 | 8.96 | 4.53 | 10.64 | 4.89 |

| Recovery Period | 96.44 | 49.16 | 2.45 | 1.12 | 7.33 | 4.33 | 11.68 | 5.33 |

Note. RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; HRV = High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability (ln-transformed); NA = Negative Affect; SD = Standard Deviation.

Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Employment of the different regulatory strategies was moderately-to-strongly correlated, suggesting that overall, individuals who engaged in a given strategy were likely to engage in other strategies too. In addition, as expected, indices of parasympathetic withdrawal to the sad film (RSA reactivity and HRV reactivity) were highly correlated, yet were not completely overlapping, with 58% shared variance. Similarly, indices of parasympathetic augmentation during the recovery period (RSA recovery and HRV recovery) also were highly correlated, with 46% shared variance. Reappraisal was significantly correlated with greater recovery of NA and PA during the recovery period; suppression was correlated with greater recovery of PA, whereas distraction was not correlated with recovery of NA or PA. None of the indices of parasympathetic activity were correlated with the degree to which participants engaged in reappraisal or distraction during the recovery period.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Reappraisal | -- | .48*** | .52*** | −.05 | −.11 | .06 | .05 | .22** | .38*** |

| 2 Distraction | -- | .42*** | −.02 | −.09 | −.03 | .003 | .07 | .12 | |

| 3 Suppression | -- | −.06 | −.13 | .01 | −.03 | −.08 | .19* | ||

| 4 HRV Reactivity | -- | .68*** | .50*** | .37*** | −.08 | −.04 | |||

| 5 RSA Reactivity | -- | .38*** | .43*** | −.01 | −.10 | ||||

| 6 HRV Recovery | -- | .76*** | .03 | −.004 | |||||

| 7 RSA Recovery | -- | .07 | .01 | ||||||

| 8 ΔPANAS-NA Recovery | -- | .27*** | |||||||

| 9 ΔPANAS-PA Recovery | -- |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Note. RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; HRV = High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability; HRV/RSA Reactivity = Reductions in HRV/RSA during sad film relative to neutral film; HRV/RSA Recovery = Increases in HRV/RSA during recovery period relative to sad film; ΔPANAS-NA = Decreases in Negative Affect during recovery period relative to sad film, as measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS); ΔPANAS-PA = Increases in Positive Affect during recovery period relative to sad film, as measured by the PANAS.

Does Parasympathetic Flexibility Moderate the Associations between Spontaneous Regulation and Affect Recovery?2,3

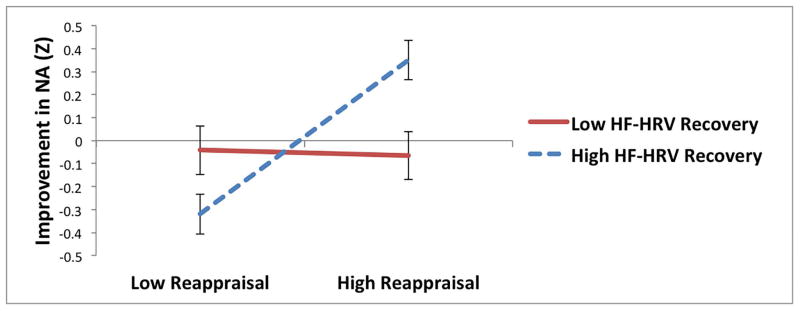

For reappraisal, neither index of parasympathetic reactivity to the sad film moderated the relationship between reappraisal and changes in NA during recovery. However, there was a significant interaction between reappraisal and recovery of HRV, such that reappraisal predicted significantly greater improvement in NA among individuals with greater HRV recovery (t = 3.86, p < .005), but not among individuals with less HRV recovery (t = −0.11, p = .92; see Table 3 and Figure 1a). Similarly, there was a significant interaction between reappraisal and recovery of RSA, such that reappraisal predicted significantly greater improvement in NA among individuals with greater RSA recovery (t = 3.62, p < .0005), but not among individuals with less RSA recovery (t = 0.69, p = .49; see Table 3 and Figure 1b).

Table 3.

Interactions between Parasympathetic Responses to a Sad Film and Regulatory Strategies Predicting Changes in Negative Affect Following Sad Film

| Reappraisal as Predictor | B | t | Distraction as Predictor | B | t | Suppression as Predictor | B | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reappraisal | 0.19 | 2.85** | Distraction | 0.08 | 1.20 | Suppression | −0.06 | −0.87 |

| HRV Reactivity | −0.06 | −0.83 | HRV Reactivity | −0.05 | −0.73 | HRV Reactivity | −0.03 | −0.44 |

| HRV Reactivity x Reappraisal | 0.06 | 0.81 | HRV Reactivity x Distraction | 0.14 | 1.81 | HRV Reactivity x Suppression | 0.14 | 2.28* |

|

| ||||||||

| Reappraisal | 0.20 | 2.97** | Distraction | 0.09 | 1.30 | Suppression | −0.09 | −1.29 |

| RSA Reactivity | 0.02 | 0.32 | RSA Reactivity | −0.002 | 0.04 | RSA Reactivity | −0.01 | −0.10 |

| RSA Reactivity x Reappraisal | 0.09 | 1.23 | RSA Reactivity x Distraction | 0.18 | 2.45* | RSA Reactivity x Suppression | 0.11 | 1.48 |

|

| ||||||||

| Reappraisal | 0.16 | 2.39* | Distraction | 0.08 | 1.15 | Suppression | −0.07 | −0.96 |

| HRV Recovery | 0.03 | 0.50 | HRV Recovery | 0.06 | 0.87 | HRV Recovery | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| HRV Recovery x Reappraisal | 0.17 | 2.51* | HRV Recovery x Distraction | 0.17 | 2.58* | HRV Recovery x Suppression | 0.07 | 1.22 |

|

| ||||||||

| Reappraisal | 0.19 | 2.81** | Distraction | 0.07 | 1.02 | Suppression | −0.08 | −1.14 |

| RSA Recovery | 0.02 | 0.28 | RSA Recovery | 0.05 | 0.76 | RSA Recovery | 0.05 | 0.74 |

| RSA Recovery x Reappraisal | 0.13 | 2.16* | RSA Recovery x Distraction | 0.06 | 0.81 | RSA Recovery x Suppression | −0.08 | −1.23 |

p < .01,

p < .05.

Note. RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; HRV = High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability; HRV/RSA Reactivity = Reductions in HRV/RSA during sad film relative to neutral film; HRV/RSA Recovery = Increases in HRV/RSA during recovery period relative to sad film. Baseline levels of HRV or RSA (not displayed) also were included as covariates in each analysis.

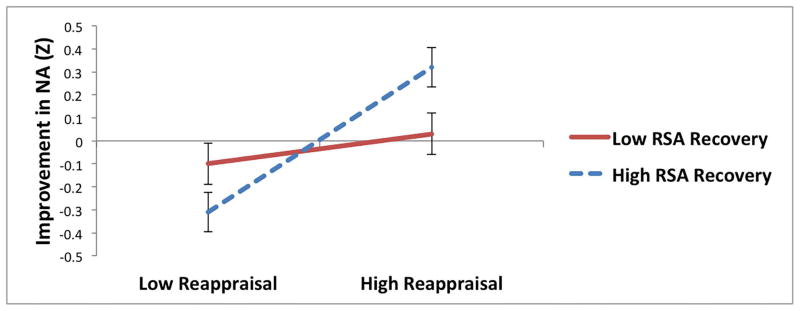

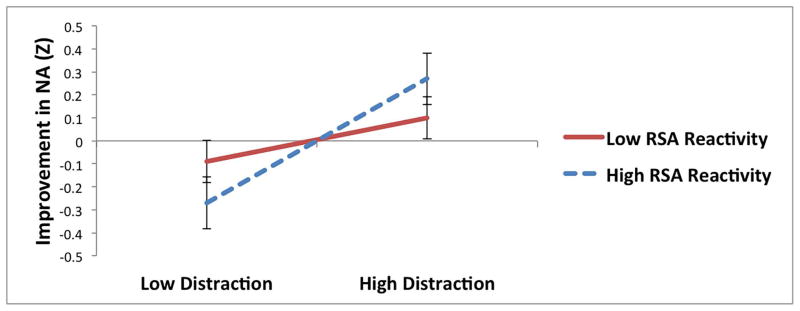

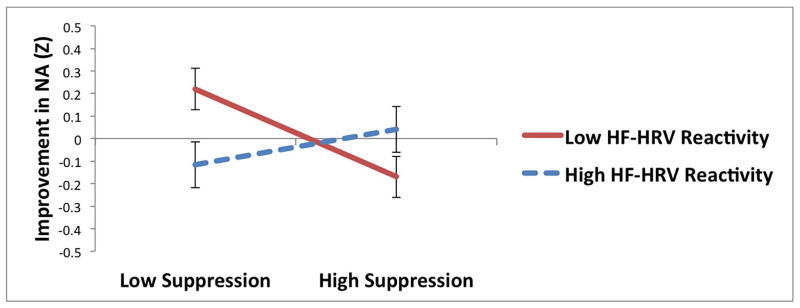

Figure 1.

Interactions between parasympathetic responses to a sad film and reappraisal (a and b), distraction (c and d), and suppression (e) predicting improvement in negative affect (NA) following the sad film (Z-standardized; greater improvement represents greater decreases in NA during the recovery period).

For distraction, HRV reactivity to the sad film moderated the relationship between distraction and changes in NA during recovery only at a trend level. However, there was a significant interaction between RSA reactivity and distraction; distraction predicted significantly greater improvement in NA among individuals with greater RSA reactivity to the sad film (t = 2.39, p = .02), but not among individuals with less RSA reactivity (t = −0.83, p = .41; see Table 3 and Figure 1c). Additionally, there was a significant interaction between distraction and recovery of HRV, such that distraction predicted significantly greater improvement in NA among individuals with greater HRV recovery (t = 2.50, p = .01), but not among individuals with less HRV recovery (t = −1.04, p = .30; see Table 3 and Figure 1d). RSA recovery did not moderate the relationship between distraction and changes in NA during recovery.4

For suppression, HRV reactivity to the sad film significantly moderated the relationship between suppression and changes in NA during recovery. Consistent with hypotheses, suppression was associated with increases in NA during recovery among individuals with less HRV reactivity to the sad film (t = −2.36, p = .02; see Table 3 and Figure 1e), but not among individuals with greater HRV reactivity (t = 0.81, p = .42), suggesting that HRV reactivity protected against the maladaptive effects of suppression on NA recovery. None of the other interactions between suppression and parasympathetic flexibility were significant.

Testing Alternative Models: Does Affect Recovery Moderate the Association between Spontaneous Regulation and Parasympathetic Recovery?

Given the difficulty in discerning temporality of these constructs due to the cross-sectional nature of the data and overlapping time-frame of parasympathetic recovery and affect recovery assessment, we also tested alternative models by which spontaneous regulation might lead to parasympathetic recovery. Although none of the spontaneous regulation strategies were associated with changes in parasympathetic activity during the recovery period overall (see Table 1), we examined whether affect recovery (following the recovery period) might facilitate parasympathetic recovery when individuals engaged in adaptive regulatory strategies.

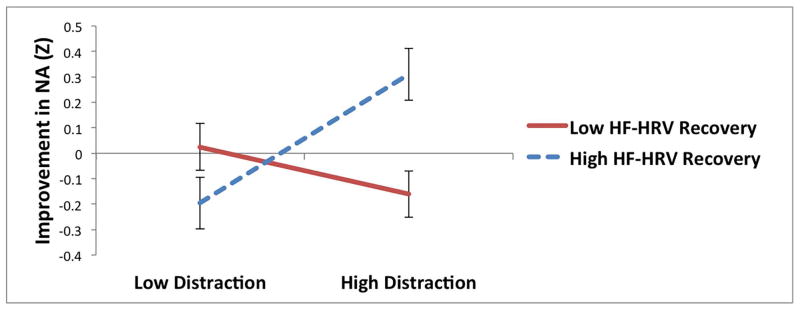

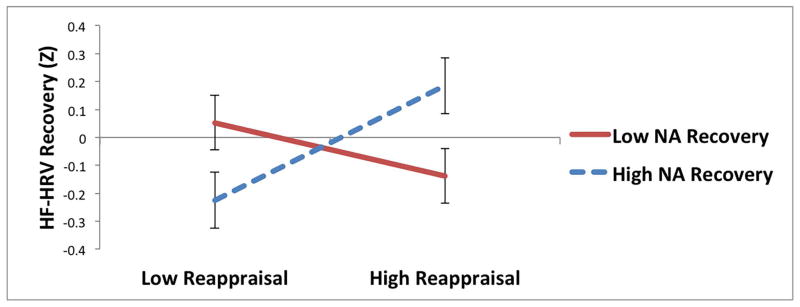

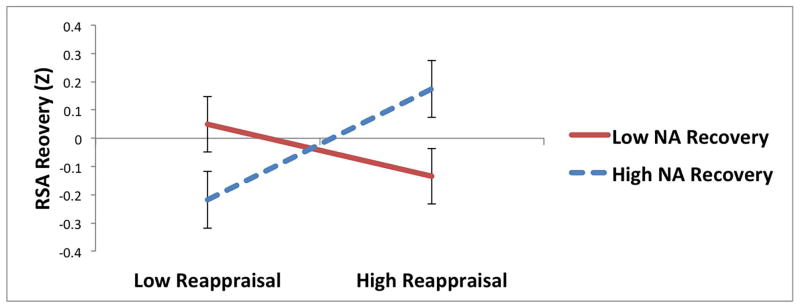

For reappraisal, there were significant interactions with NA recovery predicting HRV recovery and RSA recovery (Table 4; Figure 2a and b). Among individuals who experienced greater improvements in NA during the recovery period, reappraisal was associated with greater recovery of HF-HRV (t = 2.02, p = .04; Figure 2a) and marginally greater recovery of RSA (t = 1.91, p = .06; Figure 2b); among individuals with less improvement in NA, reappraisal was not associated with recovery of HF-HRV (t = −0.98, p = .33) and or recovery of RSA (t = −0.95, p = .34). There were no other significant interactions between regulatory strategies (reappraisal, distraction, or suppression) and changes in NA (Table 4) or PA (ps > .06) predicting parasympathetic recovery.5

Table 4.

Interactions between Regulatory Strategies and Changes in Negative Affect Following Sad Film Predicting Parasympathetic Recovery from Sad Film

| Outcome | Reappraisal as Predictor | B | t | Distraction as Predictor | B | t | Suppression as Predictor | B | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRV Recovery | Reappraisal | 0.06 | 0.75 | Distraction | 0.07 | 0.91 | Suppression | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| NA Recovery | 0.01 | 0.14 | NA Recovery | 0.04 | 0.38 | NA Recovery | 0.08 | 0.96 | |

| NA Recovery x Reappraisal | 0.16 | 2.27* | NA Recovery x Distraction | 0.09 | 1.18 | NA Recovery x Suppression | 0.03 | 0.50 | |

|

| |||||||||

| RSA Recovery | Reappraisal | 0.05 | 0.69 | Distraction | 0.07 | 0.81 | Suppression | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| NA Recovery | 0.01 | 0.13 | NA Recovery | 0.08 | 0.83 | NA Recovery | 0.08 | 0.94 | |

| NA Recovery x Reappraisal | 0.16 | 2.17* | NA Recovery x Distraction | 0.001 | 0.01 | NA Recovery x Suppression | −0.07 | −1.13 | |

p < .05.

Note. RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; HRV = High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability; HRV/RSA Recovery = Increases in HRV/RSA during recovery period relative to sad film. Baseline levels of NA also were included as covariates in each analysis.

Figure 2.

Interactions between reappraisal and changes in negative affect (NA) predicting recovery of (increases in) (a) high-frequency heart rate variability (HF-HRV) and (b) respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) during recovery period following sad film.

Discussion

This is the first study to directly evaluate the extent to which parasympathetic flexibility modulates the adaptive, uninstructed downregulation of NA following a sad film. Consistent with hypotheses, we found that the use of distraction was associated with improvement in NA, but only among individuals who demonstrated greater reductions in RSA in response to the sad film, or greater increases in HRV during recovery from sadness. Similarly, the use of cognitive reappraisal was associated with improvement in NA, but only among individuals who demonstrated greater increases in RSA or HRV during recovery from the sad film. In contrast, the putatively maladaptive strategy of suppression predicted increases in NA among individuals with less HRV reactivity, but predicted greater improvement in PA among individuals with greater HRV recovery. These results provide initial evidence that contextually-appropriate (or flexible) parasympathetic reactivity and recovery in response to loss-related NA may facilitate the success of affect regulation strategies, whereas poorer parasympathetic reactivity and recovery could attenuate the effectiveness of these strategies.

This study suggests that putatively adaptive regulatory strategies may not be universally effective in the regulation of NA (e.g., Aldao, 2013; Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Sheppes et al., 2014). Specifically, lacking appropriate vagal withdrawal to affective challenges or appropriate vagal recovery may result in difficulty mobilizing physiological resources to adequately respond to these challenges, even if adaptive regulatory strategies such as reappraisal and distraction are employed. Given that atypical RSA fluctuations appear to index an endophenotype of depression (Yaroslavsky et al., 2014), the present results suggest that one mechanism by which impairments in parasympathetic flexibility could confer risk for affective disorders is via an attenuated ability to benefit from the use of adaptive regulatory strategies when they are implemented.

Greater vagal withdrawal to the sad film appeared to facilitate the effectiveness only of distraction, and for withdrawal of RSA but not HRV. In contrast, poorer vagal withdrawal to the sad film (for HRV) appeared to exacerbate the effects of suppression on increases in NA. Although the evidence was not as strong as we anticipated, these findings support research that suggests that RSA withdrawal to sad films may represent the ability to effectively engage with sad stimuli and adaptively regulate negative affect (e.g., Rottenberg et al., 2005; Gentzler et al., 2009; LeMoult et al., 2016; Yaroslavsky et al., 2013). The rapid withdrawal of the vagal brake may help individuals to meet changing environmental demands, such as increasing attention and information processing (Suess, Porges, & Plude, 1994) and coping with negative affect (Beauchaine, 2001), both of which are likely to be adaptive responses in the context of NA. Broadly, RSA reactivity to NA could reflect emotional and behavioral adaptability that facilitates goal-directed behavior, such as the ability to attend to sad stimuli when relevant, or preparing the body for a regulatory response (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Thayer & Lane, 2009). Thus, RSA reactivity may be an important substrate for flexible self-regulation in response to affective challenges.

Greater vagal augmentation during the uninstructed recovery period following the sad film was associated with greater regulatory success when using reappraisal (for RSA and HRV), distraction (for HRV, but not RSA), and suppression (for HRV when predicting PA). In contrast, an alternative set of models tested a reverse hypothesis that the combination of adaptive regulation and affective recovery would predict improved parasympathetic recovery. This alternative hypothesis was partially supported, with reappraisal (but not distraction or suppression) predicting greater recovery of HRV and RSA, but only when individuals also experienced greater reductions in NA. Thus, these parallel analyses suggest that reappraisal may be useful for improving NA and restoring parasympathetic activity, but that changes in NA and parasympathetic activity may influence one another to a greater degree when reappraisal is implemented. Although speculative given the correlational nature and overlapping time-frame of these data, parasympathetic recovery could facilitate affective recovery, and vice versa, but not in all contexts – rather, reappraisal could allow for more integrated affective and autonomic recovery from NA. This work is consistent with a broad literature supporting the affective benefits of reappraisal (Gross, 2013; Webb et al., 2012) and extends it to understanding the role of reappraisal in autonomic recovery following NA. It is not clear from the present data whether reappraisal influences parasympathetic recovery, which facilitates affective recovery, or whether reappraisal may influence affective recovery, which then is reflected in improved recovery of parasympathetic activity. Notably, although RSA recovery and regulatory strategies were assessed over the same recovery period and some evidence was obtained for bidirectionality of effects on affect, we also obtained some evidence that RSA reactivity to the sad film (which did not overlap with the period in which regulatory strategies were assessed) also was associated with the success of regulatory strategies that were used in the subsequent period. This provides support for the hypothesis that parasympathetic flexibility that occurs before regulation could influence changes in affect that occur later once regulation occurs (even after controlling for earlier levels of affect). Nevertheless, using smaller time windows and experimental designs (e.g., by manipulating biofeedback) could allow for more precision of evaluating the directionality of such relationships between parasympathetic and affective variability and the role of regulatory strategies in these relationships.

Although there was not significant vagal augmentation during the recovery period across individuals, individual differences in vagal augmentation appeared particularly relevant to the effective regulation of NA. These results support prior studies indicating that depressed individuals have attenuated recovery of RSA during crying (Rottenberg et al., 2003) and during stressor tasks (Bylsma et al., 2014; Rottenberg et al., 2007), relative to controls. This blunted recovery of vagal control while recovering from the sad film potentially could represent a greater degree of perceived threat or salience of NA, even when the film no longer is immediately objectively relevant to the task at hand. Thus, attenuated augmentation of vagal control during recovery from the sad film, and a lack of parasympathetic resources to effectively maintain adaptive affect regulation strategies, could interfere with the ability to successfully downregulate NA. Additionally, although cognitive control was not evaluated in the present report, prior studies have suggested that vagal control is associated with inhibitory control, perhaps via similar neural pathways (Thayer et al., 2012). In addition, the use of cognitive affect regulation strategies such as reappraisal and distraction is partially dependent on the presence of intact cognitive control, such as the ability to switch between ways of thinking, the ability to inhibit focus on irrelevant stimuli, and the ability to remove information from working memory when it no longer is relevant (Joormann & Vanderlind, 2014). Prior studies have demonstrated that components of cognitive control may facilitate the effective implementation of cognitive regulatory strategies (Hendricks & Buchanan, 2015; Pe et al., 2013). Thus, one reason that adaptive regulatory strategies appeared to be most effective among individuals who demonstrated greater parasympathetic recovery in the present study may be that these individuals had superior cognitive control (e.g., as reflected by increases in inhibitory vagal control during recovery from the sad film).

The effectiveness of expressive suppression in improving affect appeared to differ depending on autonomic context, with suppression predicting poorer affective recovery in the context of low vagal withdrawal to the sad film, but superior affective recovery in the context of high vagal recovery. These results suggest that suppression is a strategy that is not necessarily always maladaptive; rather, its effectiveness may depend on the context, a concept proposed in prior theoretical (Aldao, 2013; Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Sheppes et al., 2014) and empirical work (Birk & Bonanno, 2016; Bonanno et al., 2004; Burton & Bonanno, 2016; Westphal et al., 2010). Parasympathetic flexibility may represent one context in which suppression can be adaptive, at least in improving state PA. Nevertheless, this study suggests that among individuals who lack appropriate vagal withdrawal to sad stimuli, suppression may be counterproductive in attenuating NA. Although we only evaluated one type of regulatory context (responses to NA), this work extends the literature on the role of context in affect regulation by evaluating regulatory effectiveness in terms of individuals’ autonomic context, perhaps representing the physiological capacity for the effective regulation of affect (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Porges, 2007; Rottenberg, 2007a; Thayer & Lane, 2009).

The present study has several possible implications for future research. Given that parasympathetic flexibility and affect regulation are malleable, evaluating autonomic reactivity may be useful for identifying individuals who have difficulty regulating affective responses to loss, and who may benefit from interventions to attenuate risk. Biofeedback is one intervention that has promise for helping individuals to directly improve their parasympathetic activity in response to emotional stimuli (e.g., Nolan et al., 2007). There is some evidence that mindfulness meditation also may be useful for improving resting levels of parasympathetic activity (e.g., Krygier et al., 2013). For example, focusing attention on stimuli other than those that are emotionally salient (as is taught in mindfulness) may engage neural regions such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex that are involved in regulation, thereby reducing amygdala activation and leading to reductions in subjective negative affect (Denkova, Dolcos, & Dolcos, 2015). Emerging neurocognitive approaches also hold promise for improving autonomic activity; for example, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be able to directly improve HRV responses to stress (Remue et al., 2016). An important question for future research will be to determine whether improving parasympathetic flexibility in response to sadness would improve the effectiveness of regulatory responses. If so, these interventions potentially could be translated to facilitate the development of resilience, or to treat psychological disorders characterized by ineffective affect regulation.

In addition, future research should evaluate the specificity of parasympathetic flexibility in relation to the regulation of other types of affect. In the present study, we only evaluated parasympathetic activity in relation to a sad film. However, given that RSA is thought to index the capacity for flexible emotion regulation (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010) and that vagal withdrawal and recovery typically is adaptive in response to a variety of stressors (e.g., Hamilton & Alloy, 2016; Panaite et al., 2016), it is possible that contextually-appropriate fluctuations in vagal activity in response to other situations would facilitate the regulation of other specific types of affect, a direction that remains to be tested in future work. Finally, greater parasympathetic reactivity (vagal withdrawal to stimuli) generally is considered to be adaptive (Rottenberg, 2007), and increases in NA are considered contextually appropriate in the context of sad stimuli. Indeed, depression often is characterized by emotion context insensitivity, or a lack of fluctuations in emotional and autonomic responses to meet the demands of varying situations (Bylsma, Morris, & Rottenberg, 2008; Rottenberg, 2007b; Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2010). However, some evidence exists that affective reactivity that is excessively strong or persistent is maladaptive (Nock et al., 2008). This apparent conflict, the bounds of which could be evaluated in more detail in future work, might be resolved by the possibility that moderate affective and parasympathetic reactivity may be the most adaptive, as too little or too much reactivity may be associated with maladjustment (e.g., Marcovitch et al., 2010; Kogan et al., 2013). Furthermore, there may be a distinction between the extent to which self-reported affective reactivity is concordant with physiological reactivity, thereby indicating a discrepancy in perceived emotional intensity and physiological reactivity, which may have effects warranting further examination. In addition, results in the present study generally were comparable regardless of whether HRV or RSA was used to index parasympathetic flexibility. Although not surprising given prior work demonstrating the similarity in these measurements (Allen et al., 2007; Grossman et al., 1990), future studies could consider using both techniques to determine whether there are contexts in which one is predictively superior to the other, or to generate latent variables that better model the true underlying construct of vagal control.

The present study had a number of limitations. First, although evaluating regulatory strategies that individuals choose to use could have ecological validity for how participants choose to regulate affective experiences outside of the laboratory setting (e.g., Egloff et al., 2006), the correlational nature of the study (i.e., we did not manipulate the use of regulatory strategies or parasympathetic activity) limits the conclusions we can make about the causality of the relationships detected here. Future experimental studies are needed to determine whether manipulating regulatory strategies leads to greater affective recovery among individuals with flexible parasympathetic responses, and whether manipulating parasympathetic activity (e.g., using biofeedback) would improve the effectiveness of these regulatory strategies. Additionally, because we were interested in regulation and recovery in response to NA, regulation and recovery were assessed over the same period of time, which could compromise the independence of the measures. Future studies could assess these constructs on non-overlapping, more fine-grained time scales, or could evaluate physiological responses to different sets of stimuli (e.g., to other sad films) to create latent variables that may have more independence from one another. We only evaluated three types of regulatory responses; thus, it is unclear to what extent parasympathetic flexibility would moderate effects of strategies such as acceptance or rumination. In addition, we did not evaluate other related strategies or constructs that are thought to be adaptive, such as acceptance, mindfulness, emotional awareness or emotional clarity. We evaluated spontaneous regulatory strategies that were implemented during the recovery period, but not strategies used during the sad film itself; thus, it is possible that these or other relevant strategies were implemented during the sad film that were not assessed (e.g., mind-wandering, avoidance of film stimuli).

Next, regulatory strategies were evaluated by self-report, but it is not clear whether individuals actually implemented these strategies in the “intended” manner. For example, it is possible that some individuals who were unsuccessful in improving their NA were trying to implement these strategies, but lacked the resources to do so (e.g., regulatory strategies could have been prematurely terminated due to intrusive thoughts that led to the persistence of NA, even though effort was applied). Relatedly, the use of a brief measure to assess state regulation that included fewer items than the original trait regulation scales could have compromised the degree to which the scales assessed the intended strategies. For example, in the suppression subscale, items assessing “I controlled my emotions” and “one could see my feelings” could overlap partially with regulatory effectiveness, perhaps in part explaining the positive correlation among all regulatory strategies and the association between suppression and PA. In addition, although the sad film paradigm has been used frequently in affective science research, the ecological validity of this paradigm (and of parasympathetic reactivity and recovery) to real-world responses to personally-relevant losses is not entirely clear. The measure of affect we used (the PANAS) assesses general NA but does not include sadness; this sacrifice was made for the sake of brevity to minimize interference with naturally-occurring reactivity and recovery processes. However, it is possible that this measure was not as sensitive as a measure that includes sadness would be, and that this might have prevented us from detecting additional relationships that were not significant in the present analyses using the general affective measures of NA and PA. The study also was composed of a nonclinical sample of university students, most of whom were young adults; thus, the results cannot necessarily be extended to the general public, to older adults, or to individuals with psychopathology, for whom emotion processing and regulation may differ. Future research should evaluate whether these results generalize to other populations. Finally, although our primary results remained after accounting for potential confounds such as respiration, heart rate, antidepressant use, BMI, and demographic characteristics, we cannot rule out other possible factors such as physical activity and smoking, which were not assessed.

The present study found that parasympathetic flexibility in response to NA was associated with greater effectiveness of cognitive reappraisal and distraction, and reduced ineffectiveness of expressive suppression, in reducing negative affect. These results lend support to theories of self-regulation that suggest that context is important in determining when regulatory strategies lead to adaptive outcomes (e.g., Aldao, 2013; Aldao, Sheppes, & Gross, 2015; Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Stange, Alloy, & Fresco, in press). Future research is needed to determine how the present results map onto regulation and affective responses in daily life and among individuals with more severe difficulties with emotion regulation. In conclusion, the present study suggests that flexibility of the parasympathetic nervous system in response to NA holds promise for improving our understanding of contextual and biological factors that facilitate the regulation of negative affect, and for targeting these mechanisms to prevent excessive suffering following loss.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to Jonathan P. Stange from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31MH099761), the Association for Psychological Science, the American Psychological Foundation, and the American Psychological Association. Jonathan P. Stange was supported by NIMH grant 5T32MH067631-12. Jessica L. Hamilton was supported by National Research Service Award F31MH106184 from NIMH. Lauren B. Alloy was supported by NIMH Grant MH101168. David M. Fresco was supported by NHLBI Grant R01HL119977 and NINR Grant P30NR015326.

Footnotes

70% of the sample showed increases in NA following the sad film. Individuals who did not show an increase in NA used less reappraisal (t = 2.53, p = .01), but did not differ in use of distraction or suppression, or parasympathetic flexibility indices. Results largely were consistent when analyses were repeated among the subsample of individuals who showed increases in NA following the sad film.

All results were consistent when controlling for other factors that may influence parasympathetic activity, including age, race, body mass index, and use of antidepressants and other psychiatric medications (Kemp et al., 2010). When including sex as a covariate, most results remained consistent, with the following exceptions: the reappraisal x RSA recovery interaction predicting NA recovery was reduced to p = .06; the suppression x HRV reactivity interaction predicting PA became significant, with suppression predicting greater PA improvement among individuals with greater HRV reactivity (t = 3.33, p = .001), but not among those with less HRV reactivity (t = 0.67, p = .50).

Although the primary focus of the manuscript was on changes in NA given their relevance to the experimental paradigm involving sadness, we also evaluated how interactions between parasympathetic flexibility and regulation strategies predicted changes in PA. HRV recovery interacted significantly with distraction (interaction B = 0.16, t = 2.24, p = .03) and with suppression (interaction B = 0.15, t = 2.31, p = .02); the form of these interactions was such that among individuals with greater HRV recovery, distraction (B = 0.28, t = 2.68, p < .01) and suppression (B = 0.35, t = 3.42, p < .001) predicted greater increases in PA during the recovery period; in contrast, among individuals with less HRV recovery, neither distraction (B = −0.03, t = −0.34, p = .74) nor suppression (B = 0.05, t = 0.60, p = .55) were associated with changes in PA during the recovery period. None of the other candidate interactions predicting changes in PA were significant (ps > .06).

When not controlling for heart rate and respiration, the interactions between reappraisal and HRV recovery (t = 1.98, p < .05) and between distraction and HRV recovery (t = 2.40, p = .02) maintained significance; the interactions between reappraisal and RSA recovery (t = 1.16, p = .25), distraction and RSA reactivity (t = 1.42, p = .16), and suppression and HRV reactivity (t = 1.53, p = .13) were reduced to nonsignifiance; the other strategy X parasympathetic flexibility interactions tested remained nonsignificant.

When removing participants older than age 39 to create a more homogeneous young adult sample, all results were consistent with those reported in the text when using the full sample.

Contributor Information

Jonathan P. Stange, University of Illinois at Chicago

Jessica L. Hamilton, Temple University

David M. Fresco, Kent State University

Lauren B. Alloy, Temple University

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A. The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Sheppes G, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation flexibility. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2015;39(3):263–278. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9662-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JJA, Chambers AS, Towers DN. The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: A pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Psychophysiology. 2007;74:243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(2):183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Thayer JF. Heart rate variability as a transdiagnostic biomarker of psychopathology. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2015;98(2):338–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Bredemeier K. A unified model of depression integrating clinical, cognitive, biological, and evolutionary perspectives. Clinical Psychological Science. 2016;4(4):596–619. doi: 10.1177/2167702616628523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Ellis AJ, Reid RM. Heart rate variability predicts cognitive reactivity to a sad mood provocation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(5):395–403. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9324-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman E, Lieberman M. Using neuroscience to broaden emotion regulation: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3(4):475–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, … van der Molen MW. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Burton CL. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, Coifman K. The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science. 2004;15(7):482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(4):676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Salomon K, Taylor-Clift A, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity in current and remitted major depressive disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(1):66–73. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkova E, Dolcos S, Dolcos F. Neural correlates of ‘distracting’ from emotion during autobiographical recollection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2015;10(2):219–230. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff B, Schmukle SC, Burns LR, Schwerdtfeger A. Spontaneous emotion regulation during evaluated speaking tasks: associations with negative affect, anxiety expression, memory, and physiological responding. Emotion. 2006;6(3):356–366. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Tuschen-Caffier B, Schnülle J, Fischer S, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and vulnerability to depression: spontaneous versus instructed use of emotion suppression and reappraisal. Emotion. 2010;10(4):563–572. doi: 10.1037/a0019010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Regulatory control and adults’ stress-related responses to daily life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1107–1117. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Santucci AK, Kovacs M, Fox NA. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity predicts emotion regulation and depressive symptoms in at-risk and control children. Biological Psychology. 2009;82(2):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion. 2013;13(3):359–365. doi: 10.1037/a0032135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Beek JV, Wientjes C. A comparison of three quantification methods for estimation of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Psychophysiology. 1990;27(6):702–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Harvey AG, Gross JJ. When trying is not enough: Emotion regulation and the effort-success gap in bipolar disorder. Emotion. 2012;12(5):997–1003. doi: 10.1037/a0026822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Alloy LB. A typical reactivity of heart rate variability to stress and depression: Systematic review of the literature and directions for future research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;50:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks MA, Buchanan TW. Individual differences in cognitive control processes and their relationship to emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion. 2016;30(5):912–924. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1032893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt LK, McCall C, Engen HG, Singer T. Cognitive flexibility, heart rate variability, and resilience predict fine-grained regulation of arousal during prolonged threat. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(6):880–890. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A, Asnaani A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(5):409–416. doi: 10.1002/da.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, D’Avanzato C. Emotion regulation in depression: Examining the role of cognitive processes. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24(6):913–939. doi: 10.1080/02699931003784939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Vanderlind WM. Emotion regulation in depression the role of biased cognition and reduced cognitive control. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(4):402–421. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Gray MA, Felmingham KL, Brown K, Gatt JM. Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: a review and meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan A, Gruber J, Shallcross AJ, Ford BQ, Mauss IB. Too much of a good thing? Cardiac vagal tone’s nonlinear relationship with well-being. Emotion. 2013;13(4):599–604. doi: 10.1037/a0032725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Yaroslavsky I, Rottenberg J, George CJ, Baji I, Benák I, … Kapornai K. Mood repair via attention refocusing or recall of positive autobiographical memories by adolescents with pediatric-onset major depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(10):1108–1117. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Yaroslavsky I, Rottenberg J, George CJ, Kiss E, Halas K, … Makai A. Maladaptive mood repair, atypical respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and risk of a recurrent major depressive episode among adolescents with prior major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1017/S003329171600057X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig SD. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biological Psychology. 2010;84(3):394–421. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygier JR, Heathers JA, Shahrestani S, Abbott M, Gross JJ, Kemp AH. Mindfulness meditation, well-being, and heart rate variability: a preliminary investigation into the impact of intensive Vipassana meditation. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013;89(3):305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychological Science. 2010;21(7):984–991. doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMoult J, Yoon KL, Joorman J. Rumination and cognitive distraction in major Depressive Disorder: an examination of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9510-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27(3):405–416. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00251-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcovitch S, Leigh J, Calkins SD, Leerks EM, O’Brien M, Blankson AN. Moderate vagal withdrawal in 3.5-year-old children is associated with optimal performance on executive function tasks. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52(6):603–608. doi: 10.1002/dev.20462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner K, Muth ER, Herbert BM. Bradygastric activity of the stomach predicts disgust sensitivity and perceived disgust intensity. Biological Psychology. 2011;86(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa ES, Kelsey RM, Katkin ES, Sloan RP. Vagal rebound and recovery from psychological stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:650–657. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00018. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Wedig MM, Holmberg EB, Hooley JM. The emotion reactivity scale: development, evaluation, and relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan RP, Kamath MV, Floras JS, Stanley J, Pang C, Picton P, Young QR. Heart rate variability biofeedback as a behavioral neurocardiac intervention to enhance vagal heart rate control. American Heart Journal. 2005;149(6):1137e1–1137.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MF, Allen JJ, Kaszniak AW. Emotional disclosure for whom?: A study of vagal tone in bereavement. Biological Psychology. 2005;68(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek TJ, van Boxtel A, Westerink JH. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia responses to induced emotional states: effects of RSA indices, emotion induction method, age, and sex. Biological Psychology. 2012;91(1):128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Tompkins WJ. A real-time QRS detection algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1985;32(3):230–236. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1985.325532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaite V, Hindash AC, Bylsma LM, Small BJ, Salomon K, Rottenberg J. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity to a sad film predicts depression symptom improvement and symptomatic trajectory. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2016;99:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe ML, Raes F, Koval P, Brans K, Verduyn P, Kuppens P. Interference resolution moderates the impact of rumination and reappraisal on affective experiences in daily life. Cognition & Emotion. 2013;27(3):492–501. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.719489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology. 2007;74(2):116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remue J, Vanderhasselt MA, Baeken C, Rossi V, Tullo J, De Raedt R. The effect of a single HF-rTMS session over the left DLPFC on the physiological stress response as measured by heart rate variability. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(6):756–766. doi: 10.1037/neu0000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J. Cardiac vagal control in depression: a critical analysis. Biological Psychology. 2007;74(2):200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Clift A, Bolden S, Salomon K. RSA fluctuation in major depressive disorder. Psychophysiology. 2007a;44(3):450–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Ray RD, Gross JJ. Emotion elicitation using films. In: Coan JA, Allen JJB, editors. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Salomon K, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Vagal withdrawal to a sad film predicts subsequent recovery from depression. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(3):277–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Vagal rebound during resolution of tearful crying among depressed and nondepressed individuals. Psychophysiology. 2003;40(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santucci AK, Silk JS, Shaw DS, Gentzler A, Fox NA, Kovacs M. Vagal tone and temperament as predictors of emotion regulation strategies in young children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50(3):205–216. doi: 10.1002/dev.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppes G, Scheibe S, Suri G, Radu P, Blechert J, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation choice: a conceptual framework and supporting evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143(1):163–181. doi: 10.1037/a0030831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Epstein EM. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia predicts written disclosure outcome. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(5):611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Alloy LB, Fresco DM. Inflexibility and vulnerability to depression: A systematic qualitative review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12201. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Hamilton JL, Olino TM, Fresco DM, Alloy LB. Autonomic reactivity and vulnerability to depression: A multi-wave study. Emotion. doi: 10.1037/emo0000254. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suess PE, Porges SW, Plude DJ. Cardiac vagal tone and sustained attention in school-age children. Psychophysiology. 1994;31(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electophysiology. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. European Heart Journal. 1996;17:354–381. n/a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Åhs F, Fredrikson M, Sollers JJ, Wager TD. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36(2):747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Lane RD. Claude Bernard and the heart-brain connection: further elaboration of a model of neurovisceral integration. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review. 2009;33(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenza G, Nardelli M, Lanata A, Gentili C, Bertschy G, Paradiso R, Scilingo EP. Wearable monitoring for mood recognition in bipolar disorder based on history-dependent long-term heart rate variability analysis. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2014;18(5):1625–1635. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2013.2290382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev CA, Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Mead HK, Gatzke-Kopp LM. Correspondence between physiological and self-report measures of emotion dysregulation: A longitudinal investigation of youth with and without psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(11):1357–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volokhov RN, Demaree HA. Spontaneous emotion regulation to positive and negative stimuli. Brain and Cognition. 2010;73:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Miles E, Sheeran P. Dealing with feeling: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(4):775–808. doi: 10.1037/a0027600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M, Seivert NH, Bonanno GA. Expressive flexibility. Emotion. 2010;10(1):92–100. doi: 10.1037/a0018420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody ML, Gibb BE. Integrating NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) into depression research. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;4:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaroslavsky I, Bylsma LM, Rottenberg J, Kovacs M. Combinations of resting RSA and RSA reactivity impact maladaptive mood repair and depression symptoms. Biological Psychology. 2013;94(2):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]