Abstract

An angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign mesenchymal tumor characterized by proliferation of mature vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue. AMLs most commonly occur in the kidney but have been reported in a variety of extrarenal sites. Mediastinal AMLs are extremely rare. We herein present a case of a large AML of the mediastinum that was successfully treated by thoracoscopic resection.

Keywords: Mediastinal neoplasms, angiomyolipoma (AML), video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS)

Introduction

An angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign tumor characterized by the presence of mature or immature fat tissue, thick-walled blood vessels, and smooth muscles (1-3). An AML usually occurs in the kidney as an isolated phenomenon or as part of the syndromes associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (4,5). AMLs of the mediastinum are extremely rare (2,6). To the best of our knowledge, only 10 cases of mediastinal AML have been previously reported in the English-language literature (1-10). The present report is the first description of a mediastinal AML that was successfully treated using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).

Case presentation

A 69-year-old man was referred to our institution for treatment of a large mediastinal mass that had been incidentally detected on abdominal computed tomography (CT) conducted for evaluation of a 2-year history of vague epigastric discomfort. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension and atrophic gastritis. Upon admission, the patient complained of diffuse epigastric discomfort. No pulmonary symptoms or signs and no other abnormalities were found during the physical examination. Standard laboratory values were within the reference ranges. Contrast-enhanced CT showed a large circumscribed tumor with a focal fatty area in the posterior mediastinum (10×6 cm) and two simple cysts on the left kidney (Figure 1A-C). We considered the possibility of a mediastinal liposarcoma. VATS was planned without preoperative tissue confirmation because of concerns about needle-track seeding. VATS was performed using a three-incision technique with a 6-cm utility incision. A working port was located in the mid-axillary line in the 8th intercostal space. Additional two ports were placed in the 6th intercostal space in the anterior axillary line (10 mm), and the posterior axillary line in the 9th intercostal space (10 mm). Thoracoscopic exploration revealed fibrous adhesions on the entire surface of the mass without true invasion of adjacent tissues. Macroscopically, the tumor appeared to have been totally removed (Figure 2) (11). Its size was 16×14×3 cm. To avoid rib spreading, the tumor was divided into two fragments in a retrieval bag. Histologic examination revealed mesenchymal cell proliferation comprising mature fat, capillaries, and smooth muscle fibers (Figure 3).

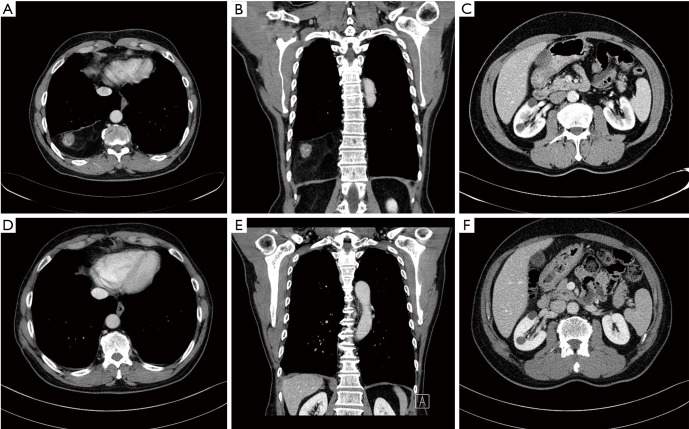

Figure 1.

Radiological findings of angiomyolipoma. (A,B) Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a well-circumscribed, heterogeneously enhancing mass with a focal fatty area; (C) contrast-enhanced CT showed two simple cysts on the left kidney; (D,E) follow-up CT revealed no evidence of recurrence; (F) follow-up CT showed no interval growth of the renal cysts. CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Mediastinal tumor excision (11). The operative findings revealed fibrous adhesion on the entire surface of the mass without true invasion of adjacent tissues. Thoracoscopic resection was performed, and the postoperative pathological diagnosis was an angiomyolipoma. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1538

Figure 3.

Pathological findings of angiomyolipoma. (A) Low magnification (×10) and (B,C) high magnification (×100) of the mediastinal mass showed mature fat cells with numerous admixed thick-walled blood vessels and bundles of smooth muscle cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining).

The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged home on postoperative day 7. Chest CT 1 year postoperatively revealed no evidence of recurrence or growth of the renal cysts (Figure 1D-F). However, the patient’s vague epigastric discomfort persisted at that time. He was lost to follow-up after the 1-year postoperative CT examination.

Discussion

AMLs are benign mesenchymal tumors composed of an admixture of fat, smooth muscle, and abnormal blood vessels, and the ratio of these components varies among individual patients (1-3). AMLs are usually found in the kidney. Extrarenal manifestation of AMLs is uncommon but has been reported in the skin, oropharynx, abdominal wall, gastrointestinal tract, heart, lung, liver, uterus, penis, and spinal cord. The most frequently reported extrarenal location is the liver. However, mediastinal manifestation of an AML is extremely rare (2,6).

To the best of our knowledge, only 10 cases of mediastinal AML have been previously reported in the English-language literature (1-10). The patients’ age at onset in these 10 cases ranged from 22 to 63 years (mean, 45.6 years), with an equal sex distribution (Table 1). The tumors were incidentally found in four patients (1,4,6,9). The remaining six patients had symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, dry cough, and palpitation (2,3,5,7,8,10). These symptoms varied depending on the location and size of the tumor. Only one tumor reportedly displayed malignant behavior (7). Five of 10 of these patients with a mediastinal AML had a history of nephrectomy: 3 for a renal AML and 2 for an unknown reason (4,5,7,8,10). Extrarenal AMLs are considered to be multifocal lesions rather than metastases. This multicentricity of AMLs is caused by either the congenital presence of cell precursors in multiple sites or a form of benign metastases similar to that in patients with benign metastasizing leiomyoma (3,5,10). Classic AMLs are sporadic in 90% of cases. However, 80% of patients with TSC and nearly half of patients with LAM have renal AMLs (1,10). Four of the 10 previously described patients also had TSC and/or LAM (1,4,8,10). Our patient was asymptomatic without a history of TSC or LAM. However, he had renal masses that may have been either simple cysts or AMLs. In patients with renal AMLs, the general indications for treatment are symptomatic masses and masses measuring >4 cm (12). Our patient had renal masses measuring <1.5 cm in diameter (Figure 1C,F).

Table 1. Summary of all mediastinal angiomyolipoma reported in the English literature.

| No. | Authors | Age/sex | Size (cm) | Symptoms | TSC or LAM | History of Nephrectomy | Preoperative percutaneous biopsy | Preoperative tissue confirmation | Preoperative diagnosis | Operative method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kim et al. (3) | 62/F | 4.0×3.0×3.0 | Dyspnea & cough | No | No | Yes | Yes | AML | Thoracotomy |

| 2 | Torigian et al. (10) | 35/F | 6.8×10.0×14.5 | Palpitation | TSC & LAM | Due to AML | No | No | R/O AML | Thoracotomy |

| 3 | Amir et al. (2) | 22/M | 19.0×15.0×9.0 | Dyspnea & cough | No | No | No | No | Not mentioned | Thoracotomy |

| 4 | Watts et al. (1) | 57/F | 5.7 | Asymptomatic | LAM | No | No | No | R/O thymoma | Sternotomy |

| 5 | Warth et al. (8) | 32/M | 15.0×8.0×3.0 | Dyspnea | TSC | Due to AML | No | No | R/O AML | Not mentioned, maybe thoracotomy |

| 6 | Knight et al. (9) | 57/F | 3.0×2.4×1.8 | Asymptomatic | No | No | No | No | Not mentioned | Sternotomy |

| 7 | Han et al. (5) | 50/M | 5.8×4.5, 18.0×2.5, and 15.0×12.0 | Dyspnea & cough | No | Due to AML | No | No | R/O AML | Conversion to thoracotomy |

| 8 | Morita et al. (4) | 56/F | 8.0×9.0×23.0 | Asymptomatic | LAM & suspected TSC | Due to unknown origin | No | No | R/O AML or liposarcoma | Biopsy using VATS |

| 9 | Candas et al. (6) | 22/M | 11.0×7.0 | Asymptomatic | No | No | Yes | No | R/O liposarcoma or lymphoma | Thoracotomy |

| 10 | Liang et al. (7) | 63/M | 6.7×9.8 | Chest pain | No | Due to unknown origin | Yes | Yes | AML | Not mentioned, maybe thoracotomy |

AML, angiomyolipoma; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; R/O, rule out; F, female; M, male.

There are no guidelines that indicate how frequently renal AMLs should be imaged when they are managed by surveillance. In addition, sporadic AMLs tend to exhibit a much slower growth rate than do AMLs in patients with TSC (12).

Treatment options for renal AMLs have traditionally included radical and partial nephrectomy, transarterial embolization, and ablative therapies. Transarterial embolization has recently emerged as a first-line management option for AMLs, especially in patients with acute hemorrhage and refractory hemodynamic instability (12). Previously reported treatment options for mediastinal AMLs include surgical removal and transarterial embolization (2,3,6,13). In nine patients with mediastinal AML, complete resection was achieved by thoracotomy or sternotomy (Table 1). Only one patient was treated by repeated transarterial embolization in a Japanese case report (13). AML of the mediastinum is a recently recognized variant with malignant potential (7,14,15). In addition, no long-term follow-up data are available for mediastinal AMLs. Thus, complete resection of mediastinal AMLs eliminates the small possibility of malignant transformation, which has only been reported in renal AMLs (14,15). In most cases, the preoperative diagnosis was not easy (Table 1). Thus, transarterial embolization in patients with a mediastinal AML should be carefully considered in selected patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a mediastinal AML that was completely resected using VATS. Thoracoscopic resection of certain mediastinal lesions has been increasing in frequency and has been shown to be a safe and effective alternative to open thoracotomy. In previous reports, the reason for avoidance of thoracoscopic resection was not clearly stated. In the present case, thoracoscopic resection was complex and difficult due to the large tumor size, fibrous adhesion, and slippery mass surface. However, meticulous tissue dissection allowed this mass to be removed completely without damage to the surrounding structures. Our case shows that thoracoscopic resection can be performed successfully for treatment of mediastinal AMLs.

Conclusions

Patients with mediastinal AMLs should be carefully evaluated for common manifestations such as renal AMLs, TSC, and LAM. Thoracoscopic resection of mediastinal AMLs appears to be safe and effective. Indications for resection of these tumors include diagnosis of a mediastinal mass, elimination of the possibility of malignant transformation, and relief of symptoms caused by a mass effect.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Catholic university of Korea, College of Medicine.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Watts KA, Watts JR., Jr Incidental discovery of an anterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. J Thorac Imaging 2007;22:180-1. 10.1097/01.rti.0000213571.09280.f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amir AM, Zeebregts CJ, Mulder HJ. Anterior mediastinal presentation of a giant angiomyolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:2161-3. 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01512-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YH, Kwon NY, Myung NH, et al. A case of mediastinal angiomyolipoma. Korean J Intern Med 2001;16:277-80. 10.3904/kjim.2001.16.4.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morita K, Shida Y, Shinozaki, et al. Angiomyolipomas of the mediastinum and the lung. J Thorac Imaging 2012;27:W21-3. 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31823150c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han WL, Hu J, Rusidanmu A, et al. Chylous pleural effusion caused by mediastinal angiomyolipomas. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:945-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candaș F, Berber U, Yildizhan A, et al. Anterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:1431-2. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang W, Xu S, Chen F. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm of the mediastinum and the lung: one case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e904. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warth A, Herpel E, Schmähl A, et al. Mediastinal angiomyolipomas in a male patient affected by tuberous sclerosis. Eur Respir J 2008;31:678-80. 10.1183/09031936.00021207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight CS, Cerfolio RJ, Winokur TS. Angiomyolipoma of the anterior mediastinum. Ann Diagn Pathol 2008;12:293-5. 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torigian DA, Kaiser LR, Soma LA, et al. Symptomatic dysrhythmia caused by a posterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:93-6. 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YD, Jeong SC, Choi SY, et al. Mediastinal tumor excision. Asvide 2017;4:228. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/1538

- 12.Flum AS, Hamoui N, Said MA, et al. Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Renal Angiomyolipoma. J Urol 2016;195:834-46. 10.1016/j.juro.2015.07.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe S, Sato H, Tawaraya K, et al. A case of mediastinal angiomyolipoma. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1997;45:1889-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaguchi K, Oda Y, Nakanishi K, et al. Malignant transformation of renal angiomyolipoma: a case report. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:523-9. 10.1097/00000478-200204000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi N, Kitahara R, Hishimoto Y, et al. Malignant transformation of renal angiomyolipoma. Int J Urol 2003;10:271-3. 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]