Abstract

Objectives:

Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D) is often managed with over-the-counter therapies such as loperamide, though with limited success. This analysis evaluated the efficacy of eluxadoline in patients previously treated with loperamide in two phase 3 studies.

Methods:

Adults with IBS-D (Rome III criteria) were enrolled and randomized to placebo or eluxadoline (75 or 100 mg) twice daily for 26 (IBS-3002) or 52 (IBS-3001) weeks. Patients reported loperamide use over the previous year and recorded their rescue loperamide use during the studies. The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of patients with a composite response of simultaneous improvement in abdominal pain and reduction in diarrhea.

Results:

A total of 2,428 patients were enrolled; 36.0% reported prior loperamide use, of whom 61.8% reported prior inadequate IBS-D symptom control with loperamide. Among patients with prior loperamide use, a greater proportion treated with eluxadoline (75 and 100 mg) were composite responders vs. those treated with placebo with inadequate prior symptom control, over weeks 1–12 (26.3% (P=0.001) and 27.0% (P<0.001) vs. 12.7%, respectively); similar results were observed over weeks 1–26. When daily rescue loperamide use was imputed as a nonresponse day, the composite responder rate was still higher in patients receiving eluxadoline (75 and 100 mg) vs. placebo over weeks 1–12 (P<0.001) and weeks 1–26 (P<0.001). Adverse events included nausea and abdominal pain.

Conclusions:

Eluxadoline effectively and safely treats IBS-D symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea in patients who self-report either adequate or inadequate control of their symptoms with prior loperamide treatment, with comparable efficacy and safety irrespective of the use of loperamide as a rescue medication during eluxadoline treatment.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional bowel disorder (1, 2). The global prevalence of IBS is estimated to be 11.2% (2, 3). IBS can affect all members of society, irrespective of race, creed, color, or socioeconomic status, although women are more likely to be affected by IBS than men (3). IBS is associated with significant impairment in quality of life and high rates of comorbid conditions (4) that imposes a significant socioeconomic burden to society in terms of reduced work productivity and high health-care costs (5, 6). As defined in the recent Rome criteria (1, 7), IBS can be subcategorized into three major subtypes based on stool patterns: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation, and IBS with mixed symptoms of constipation and diarrhea. IBS-D is the most common IBS subtype and comprises ∼40% of all cases (3).

Despite intensive study, there is still no well-established treatment algorithm for IBS-D. Dietary and lifestyle modifications are commonly used for initial symptom management (2), although many patients continue to suffer from chronic symptoms. Clinicians often recommend the use of the over-the-counter antidiarrheal agent loperamide, a peripheral μ-opioid receptor (OR) agonist, to relieve diarrhea (8). The μ-OR activity of loperamide decreases gastrointestinal (GI) motility that increases the duration of intestinal transit, thereby promoting fluid absorption and reducing stool frequency (9). However, there is little clinical evidence demonstrating that loperamide is effective at relieving the cardinal symptom of IBS, abdominal pain, nor does loperamide improve bloating, the second most commonly reported symptom (10, 11). At approved doses, the use of loperamide in IBS patients can lead to the development of unwanted constipation (12). Other therapeutic options for the treatment of IBS-D include alosetron, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist that is restricted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to women with chronic, severe IBS-D symptoms who have failed to respond to conventional therapy (11, 13). The antibiotic rifaximin, recently approved for the treatment of both men and women with IBS-D, can be effective in some patients, but recurrence of symptoms is common (14, 15). There is therefore a large unmet need for new therapeutic agents that provide persistent relief for the multiple symptoms of IBS-D.

Eluxadoline is a peripherally active, mixed μ-OR and κ-OR agonist and δ-OR antagonist with low systemic absorption and low oral bioavailability (16) that is approved for the treatment of adults with IBS-D in the United States (17). The mixed pharmacological profile of eluxadoline may mitigate the risk of constipation effects through unopposed μ-OR agonism as seen with agents such as loperamide, through antagonism of the δ-OR (16). The efficacy of eluxadoline was demonstrated in two large, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials in patients with IBS-D (18). Eluxadoline met the primary efficacy composite end point in these trials, demonstrating simultaneous relief of the symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea associated with IBS-D. In contrast, loperamide has not been demonstrated to relieve abdominal pain in previous clinical studies (12, 19, 20). In the phase 3 studies reported by Lembo et al. (18), prior use of loperamide and its adequacy in controlling IBS-D symptoms were captured at baseline. This presented the opportunity to determine the efficacy of eluxadoline in patients previously treated with loperamide. It was hypothesized that eluxadoline could provide effective relief of IBS symptoms in patients who reported inadequate symptom control with prior loperamide.

The primary aim of this analysis was to evaluate the efficacy of eluxadoline in patients with IBS-D who reported that they did not experience adequate symptom relief with prior loperamide therapy. This prespecified prospective subgroup analysis evaluated the composite end point response rates in the pooled data from two phase 3 studies of patients who had previously experienced adequate control of IBS-D symptoms with loperamide in the year before randomization, and patients who had not experienced adequate IBS-D symptom control with loperamide. A secondary aim of this analysis was to evaluate loperamide rescue medication use across all treatment arms of the phase 3 studies and its impact on efficacy results.

Methods

Study design

IBS-3001 and IBS-3002 were parallel-group, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter phase 3 studies in adult patients with IBS-D (18). The studies comprised a pretreatment period followed by 52 (IBS-3001) or 26 (IBS-3002) weeks of treatment, during which patients were randomized to receive eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg, or placebo, twice daily. Patients underwent a 2-week posttreatment follow-up period in IBS-3001, or a 4-week single-blind placebo withdrawal in IBS-3002. Patients were included in the studies if they were 18–80 years of age, with a diagnosis of IBS-D (Rome III Criteria (1)), and with an average worst abdominal pain score of >3.0, an average Bristol Stool Scale score for stool consistency of ≥5.5 (on a scale of 1 (hard stool) to 7 (watery diarrhea)) and ≥5 days with a Bristol Stool Scale score of ≥5, and an average IBS-D global symptom score of ≥2.0 (scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (very severe symptoms)). Patients were also required to not have used any loperamide rescue medication within 14 days before randomization. Patients with current or expected use of opioid-containing agents (e.g., antidiarrheals or opioid analgesics) were excluded.

Primary efficacy end point

The primary efficacy end point of both studies was the proportion of patients who had a composite response on ≥50% of days, comprising a simultaneous improvement in abdominal pain and a reduction in diarrhea, evaluated over the initial 12 weeks of double-blind treatment (FDA end point) and over 26 weeks of treatment (European Medicines Agency end point) (18).

Assessments

Patients were asked during the screening phase of both phase 3 studies whether they had used loperamide for their IBS-D over the past year (yes/no). Patients indicating prior loperamide use were asked whether loperamide was used acutely (defined as use for short-term relief, typically not exceeding 6 days of consecutive daily use), or chronically (defined as continuous use for maintenance therapy, typically exceeding ≥2 weeks of consecutive daily use), and whether loperamide had provided adequate control of their IBS symptoms (yes/no).

Use of over-the-counter loperamide rescue medication, purchased by the patient and reimbursed by the sponsor, was permitted during the treatment period for the acute treatment of uncontrolled diarrhea. A dose of 2 mg of loperamide was permitted once every 6 h, with the following guidelines: no more than 4 unit doses over a continuous 24 h time period (8 mg/day), no more than 7 unit doses over a continuous 48 h time period (14 mg over 2 days), and no more than 11 unit doses over a continuous 7-day time period (22 mg over 7 days). Patients were asked to record their use of loperamide rescue in electronic diaries for 26 weeks (IBS-3001) or 30 weeks (IBS-3002). Use of above the permitted amount of loperamide initiated an automatic alert to the investigator. In the event of excessive loperamide rescue use, the status of the patient was to be evaluated by the investigator as soon as possible. Treatment discontinuation in the event of excessive loperamide rescue use was at the discretion of the investigator.

Safety assessments

Safety and tolerability of eluxadoline were monitored throughout the studies through adverse event (AE) reporting, clinical laboratory assessments, 12-lead electrocardiograms, vital signs, concomitant medications, and physical examinations.

Data pooling and statistical analysis

Data for patients treated with placebo, or eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg, were pooled from IBS-3001 and IBS-3002; overall, 2,428 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive placebo (n=809), eluxadoline 75 mg (n=810), or eluxadoline 100 mg (n=809) (18). The intention-to-treat population comprised 2,423 randomized patients from IBS-3001 and IBS-3002, treated with placebo (n=809), eluxadoline 75 mg (n=808), or eluxadoline 100 mg (n=806).

Frequency distributions were used to summarize categorical variables and descriptive statistics were used to summarize continuous variables across treatment groups. All statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided hypothesis test at the 5% level of significance. A subgroup analysis was performed based on patients who reported that they did or did not experience adequate IBS-D symptom control with loperamide. The proportion of composite responders for each subgroup was analyzed using pair-wise Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel tests for active treatments vs. placebo (18). To assess the impact of loperamide rescue use on composite efficacy responder rates over weeks 1–12 and weeks 1–26, a sensitivity analysis was performed where patients were assumed to be nonresponders for the daily response on any day where rescue loperamide was used.

Results

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

In total, 2,428 patients were included in the enrolled set. The mean age ranged from 44.4±13.9 to 47.1±13.8 years, and the majority of patients were female in both studies (range across treatment groups, 64.8–68.5%) (18). The mean daily worst abdominal pain score was >6 across all treatment groups and the average number of daily bowel movements ranged from 4.7±2.2 to 5.0±3.0.

Patterns of loperamide usage in the year before randomization

Loperamide use in the year before randomization was balanced across treatment groups, and 873 (36.0%) patients reported prior loperamide use (Table 1). Of the patients with prior loperamide use, inadequate control of IBS-D symptoms with loperamide was reported in 538 patients across all treatment groups (placebo: 58.9% eluxadoline 75 mg: 67.1% eluxadoline 100 mg: 58.8%). The pattern of loperamide use before randomization tended to be mostly acute across all patients who reported prior loperamide use, ranging from 84.5 to 88.3%, whereas chronic use of loperamide before randomization was less common (Table 1).

Table 1. Loperamide use in the year before randomization: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies.

| Placebo (n=809) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n=808) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n=806) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior loperamide use, n (%) | 282 (34.9) | 295 (36.5) | 296 (36.7) |

| Patients reporting inadequate control of IBS-D symptoms with prior loperamide,a n (%) | 166 (58.9) | 198 (67.1) | 174 (58.8) |

| Loperamide usage pattern,a n (%) | |||

| Acuteb | 249 (88.3) | 252 (85.1) | 250 (84.5) |

| Chronicc | 33 (11.7) | 43 (14.5) | 46 (15.5) |

IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea.

Percentages expressed as a proportion of patients with prior loperamide use.

Acute use defined as use for short-term relief, typically not exceeding 6 days of consecutive daily use.

Chronic use defined as continuous use for maintenance therapy, typically exceeding ≥2 weeks of consecutive daily use.

Composite response rates according to prior symptom control with loperamide

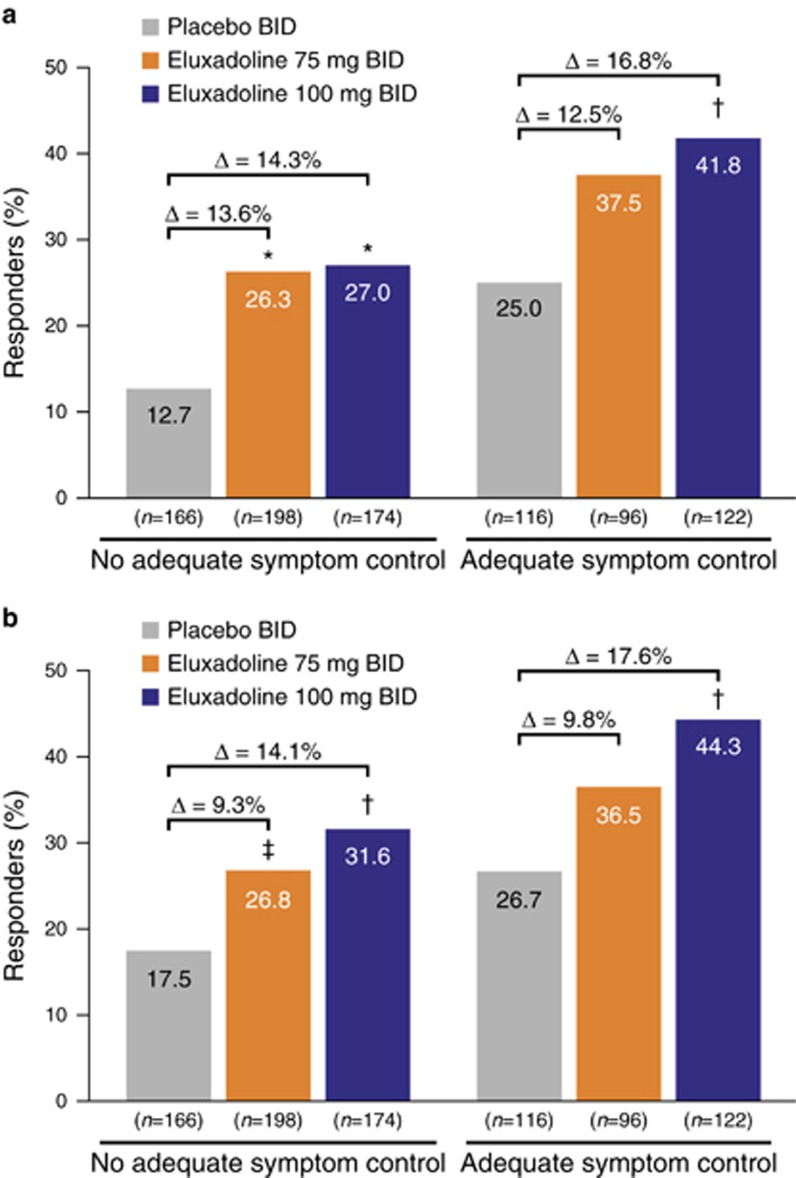

Among the patients who reported prior loperamide use with inadequate symptom control, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline were composite responders over weeks 1–12 compared with those treated with placebo (eluxadoline 100 mg: 27.0% (P<0.001) and 75 mg: 26.3% (P=0.001) vs. 12.7%, respectively) (Figure 1a). Similarly, among patients reporting prior loperamide use with adequate symptom control, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 100 mg were responders compared with those treated with placebo (41.8% (P=0.006) vs. 25.0%); there was a greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 75 mg who were responders compared with the placebo group among this subgroup, although this did not reach statistical significance. A similar pattern in composite responder rates was seen for weeks 1–26 (Figure 1b). Composite responder rates tended to be higher among those patients reporting adequate symptom control with loperamide as compared with those without adequate symptom control, irrespective of treatment group.

Figure 1.

Composite response rates by prior symptom control with loperamide during (a) weeks 1–12 and (b) weeks 1–26: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies. BID, twice daily. *P≤0.001 vs. placebo; †P<0.01 vs. placebo; ‡P<0.05 vs. placebo.

Component response rates according to prior symptom control with loperamide

Analysis of the stool consistency component of the composite end point for patients with prior loperamide use with inadequate symptom control showed similar results as the composite response rate. A significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline were stool consistency responders over weeks 1–12 compared with those treated with placebo (eluxadoline 100 mg: 35.6% (P<0.001) and 75 mg: 33.3% (P=0.002) vs. 19.3%) (Figure 2a). Similarly, of those reporting adequate symptom control, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline were stool consistency responders vs. placebo (eluxadoline 100 mg: 49.2% (P=0.012) and 75 mg: 47.9% (P=0.037) vs. 33.6%). Similar findings were observed for weeks 1–26 (Figure 2b). As seen with the composite end point, stool consistency responder rates tended to be higher in patients reporting prior adequate symptom control with loperamide, and were higher with eluxadoline 100 mg compared with the 75 mg dose.

Figure 2.

Response rates for improvement in stool consistency by prior symptom control with loperamide during (a) weeks 1–12 and (b) weeks 1–26: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies. BID, twice daily. *P≤0.001 vs. placebo; †P<0.01 vs. placebo; ‡P<0.05 vs. placebo.

For the composite component end point of abdominal pain, in patients reporting inadequate symptom control with loperamide, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 75 mg were responders over weeks 1–12 compared with those treated with placebo (eluxadoline 75 mg: 51.5% (P=0.010) vs. 38.6%) (Figure 3a). There were a greater proportion of responders in the eluxadoline 100 mg group vs. placebo, although this did not reach statistical significance. In patients reporting adequate symptom control, there were no significant differences in the proportion of responders across patients receiving eluxadoline 100 mg or 75 mg as compared with those receiving placebo. A similar pattern in abdominal pain responder rates was seen for weeks 1–26 (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Response rates for improvement in abdominal pain by prior symptom control with loperamide (a) during weeks 1–12 and (b) weeks 1–26: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies. BID, twice daily. *P≤0.001 vs. placebo; †P<0.01 vs. placebo; ‡P<0.05 vs. placebo.

Rescue loperamide use during the study period

The use of rescue loperamide through weeks 1–12 was reported in approximately one-quarter of patients, with a slightly greater percentage of patients using rescue medication in the placebo group compared with patients treated with eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg (31.3% vs. 26.7% and 25.6%, respectively; Table 2). The percent of patients reporting rescue use was cumulative and increased slightly across all treatment groups through weeks 1–26, and similar to weeks 1–12, more rescue use was reported in the placebo group compared with the eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg groups (36.0% vs. 32.8% and 31.3%, respectively).

Table 2. Patients using loperamide rescue medication during the study period: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies.

| Placebo (n=809) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n=808) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n=806) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–12 | |||

| Patients using loperamide, n (%) | 253 (31.3) | 216 (26.7) | 206 (25.6) |

| Weeks 1–26 | |||

| Patients using loperamide, n (%) | 291 (36.0) | 265 (32.8) | 252 (31.3) |

Loperamide rescue was used infrequently through weeks 1–3 and averaged <1 unit dose per week (range, 0.3–0.8 and 0.2–0.9 unit doses per week in IBS-3001 and IBS-3002, respectively). The use of loperamide rescue each week was similar across all treatment groups, and was similar between the studies. Loperamide rescue use remained <1 unit dose per week and declined from week 4 through week 26, with an average of 0.2–0.3 unit doses used per week across treatment groups in both studies (data not shown).

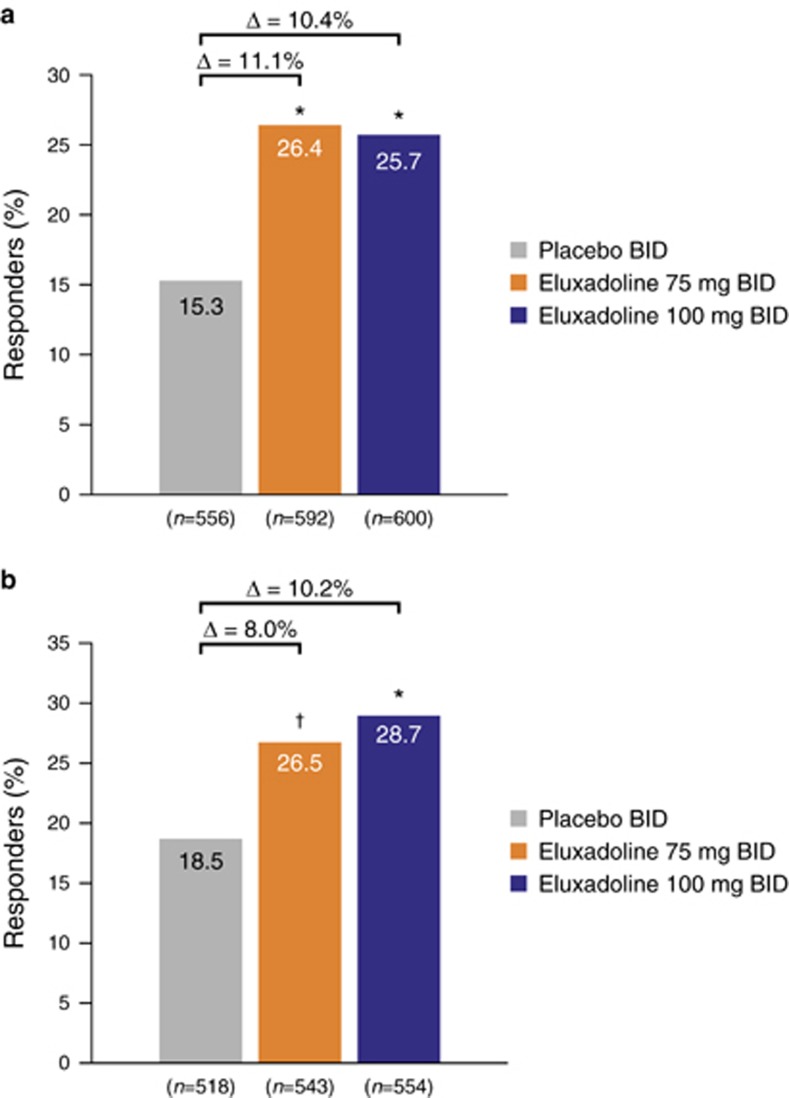

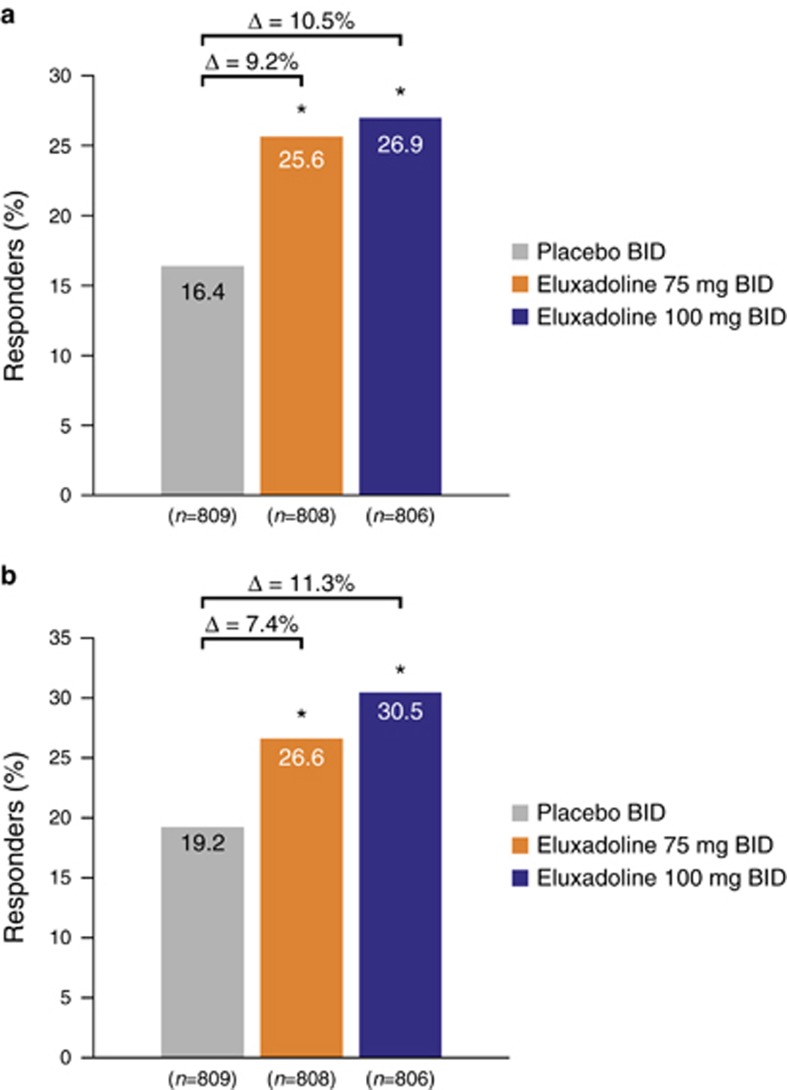

Impact of patients using loperamide rescue medication on composite response rates

Of the patients who did not use loperamide rescue at any point during the studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg were responders compared with those treated with placebo over weeks 1–12 (26.4% (P<0.001) and 25.7% (P<0.001) vs. 15.3%, respectively) and weeks 1–26 (26.5% (P<0.01) and 28.7% (P<0.001) vs. 18.5%, respectively) (Figure 4), consistent with the main findings for composite response over weeks 1–12 and weeks 1–26 (ref. (18)). When a nonresponse was imputed for each day a patient took a dose of loperamide medication, similar findings were also observed, with a greater proportion of patients treated with eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg being responders compared with those treated with placebo at both weeks 1–12 (25.6% (P<0.001) and 26.9% (P<0.001) vs. 16.4%, respectively) and weeks 1–26 (26.6% (P<0.001) and 30.5% (P<0.001) vs. 19.2%, respectively) (Figure 5), indicating that the use of loperamide rescue did not affect the overall composite responder rate.

Figure 4.

Composite response rates in patients not using any rescue loperamide during (a) weeks 1–12 and (b) weeks 1–26: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies. BID, twice daily. *P<0.001 vs. placebo; †P<0.01 vs. placebo; P values calculated using χ2 test statistic.

Figure 5.

Composite response rates with imputed nonresponse when rescue loperamide was used during (a) weeks 1–12 and (b) weeks 1–26: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies. BID, twice daily. *P<0.001 vs. placebo; P values calculated using χ2 test statistic. Patients were assumed to be nonresponders for the daily response on any day during weeks 1–12 and weeks 1–26 where rescue loperamide was used. Percentages calculated from total number of patients receiving placebo or eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg.

Safety

Overall, among patients with prior loperamide use with inadequate prior symptom control, over half in each treatment group experienced ≥1 AE (placebo: 50.6% eluxadoline 75 mg: 59.3% eluxadoline 100 mg: 61.0% Table 3). The most common AEs (occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group) were nausea, abdominal pain, constipation, and headache. GI AEs tended to be more common in eluxadoline-treated patients, although the incidence was generally low (<11% Table 3).

Table 3. AEs in patients without prior symptom control with loperamide: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies.

| AEs, n (%) | Placebo (n=166) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n=199) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n=187) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 AE | 84 (50.6) | 118 (59.3) | 114 (61.0) |

| Events | 260 | 382 | 353 |

| AEs occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group | |||

| Nausea | 9 (5.4) | 20 (10.1) | 15 (8.0) |

| Abdominal paina | 11 (6.6) | 13 (6.5) | 13 (7.0) |

| Constipation | 4 (2.4) | 14 (7.0) | 11 (5.9) |

| Headache | 5 (3.0) | 9 (4.5) | 10 (5.3) |

| Vomiting | 2 (1.2) | 8 (4.0) | 10 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 4 (2.4) | 6 (3.0) | 9 (4.8) |

| Dizziness | 3 (1.8) | 5 (2.5) | 8 (4.3) |

| Bronchitis | 5 (3.0) | 6 (3.0) | 7 (3.7) |

| Sinusitis | 6 (3.6) | 5 (2.5) | 7 (3.7) |

| ALT increased | 4 (2.4) | 5 (2.5) | 7 (3.7) |

| Fatigue | 4 (2.4) | 4 (2.0) | 6 (3.2) |

| GERD | 1 (0.6) | 5 (2.5) | 5 (2.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (4.2) | 9 (4.5) | 4 (2.1) |

| Flatulence | 4 (2.4) | 7 (3.5) | 4 (2.1) |

| Influenza | 5 (3.0) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| Arthralgia | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| Abdominal distension | 4 (2.4) | 8 (4.0) | 3 (1.6) |

| Hypertension | 3 (1.8) | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (1.8) | 5 (2.5) | 3 (1.6) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.6) |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 5 (3.0) | 7 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Back pain | 2 (1.2) | 7 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Rash | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Gastroenteritis | 4 (2.4) | 3 (1.5) | 0 |

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GERD, gastrointestinal reflux disease.

Includes upper and lower abdominal pain.

GI AEs were reported in approximately one-third of patients who used rescue loperamide during the studies, across the treatment groups (placebo: 24.7% eluxadoline 75 mg: 34.2% eluxadoline 100 mg: 31.7% Table 4). Of these patients, over half in each treatment group reported ≥1 GI AE with an onset date after a dose of loperamide (placebo: 16.6% eluxadoline 75 mg: 22.1% eluxadoline 100 mg: 21.4%). There was no clear association between the timing of loperamide rescue medication use and the reporting of GI AEs, with the majority of events reported >14 days after the most recent loperamide dose. In those patients who had used rescue loperamide during the studies, the most common GI AEs reported (occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group) included constipation, abdominal pain, and nausea (Table 4). Constipation tended to be more common in patients treated with eluxadoline 100 mg compared with eluxadoline 75 mg or placebo (6.1% vs. 3.7% and 1.4%, respectively), although incidence was generally low. The incidence of constipation in these patients was similar to that observed in the full phase 3 population safety set (placebo: 2.5% eluxadoline 75 mg: 7.4% eluxadoline 100 mg: 8.6% (B.D. Cash et al., unpublished data) (18)).

Table 4. AEs and GI AEs in patients with rescue loperamide use during study period, with onset after rescue loperamide use: pooled analysis for eluxadoline phase 3 studies.

| AEs, n (%) | Placebo (n=295) | Eluxadoline 75 mg (n=272) | Eluxadoline 100 mg (n=262) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥1 GI AE | 73 (24.7) | 93 (34.2) | 83 (31.7) |

| Patients with ≥1 GI AE with onset date following loperamide dosing | 49 (16.6) | 60 (22.1) | 56 (21.4) |

| GI AEs occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment group | |||

| Constipation | 4 (1.4) | 10 (3.7) | 16 (6.1) |

| Abdominal paina | 14 (4.7) | 14 (5.1) | 12 (4.6) |

| Nausea | 8 (2.7) | 11 (4.0) | 11 (4.2) |

| Vomiting | 4 (1.4) | 9 (3.3) | 11 (4.2) |

| Flatulence | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.8) | 6 (2.3) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.3) |

| Abdominal distension | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.2) | 3 (1.1) |

AE, adverse event; GI, gastrointestinal.

Includes upper and lower abdominal pain.

Discussion

The high prevalence of IBS (3) ensures that many health-care providers across diverse specialties will encounter patients with IBS in their practice. There is therefore a need for health-care providers to properly evaluate and treat patients with IBS. However, the treatment of IBS-D remains problematic for many providers for a number of reasons, including the lack of validated treatment guidelines, the lack of familiarity with effective therapies, the absence of prospective studies evaluating sequential therapy for IBS-D, the lack of head-to-head comparison studies directly comparing different therapeutic agents, and the inherent heterogeneity of the disease, with the result that a large proportion of patients with IBS-D express dissatisfaction with the treatment received for their IBS symptoms (21). The persistence of diarrhea in IBS-D leads many health-care providers to recommend an over-the-counter agent, such as loperamide, that is inexpensive and generally considered safe, although it has little effect on the symptoms of abdominal pain or bloating (10, 11).

Eluxadoline was approved by the FDA in May 2015 for the treatment of both men and women with IBS-D (17), and represents a treatment option for patients including those with inadequate symptom control with the common over-the-counter antidiarrheal agent loperamide. Eluxadoline significantly improved the overall symptoms of IBS-D in two large, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies involving >2,400 patients, during 12 and 26 weeks of treatment, respectively, when compared with placebo (18). The results from the present analysis demonstrate that over one-third of the patients enrolled in these two phase 3 trials reported loperamide use in the year before study enrollment; however, inadequate control of IBS-D symptoms with loperamide was reported in 59–67% of these patients. These phase 3 studies are among the largest to report on prior loperamide use in patients with IBS-D. The authors acknowledge that unanticipated selection bias may have predisposed entry of patients who had previously experienced inadequate symptom control with loperamide use, especially as the initial question only asked for recall of loperamide use within the prior year. Regardless, the cause of inadequate symptom control with loperamide in the third of patients who admitted to using loperamide is likely to be multifactorial. Importantly, the survey instrument did not capture precise reasons for treatment failure (such as persistent abdominal pain or persistent diarrhea).

The primary efficacy end point in these studies was a composite end point that required patients to achieve ≥30% improvement in abdominal pain, with a simultaneous improvement in symptoms of diarrhea (assessed using the Bristol Stool Scale) on ≥50% of days during the 12- or 26-week study period, in order to be considered a responder. The proportion of composite responders was generally greater in patients with adequate symptom control with prior loperamide vs. those with inadequate symptom control, suggesting that patients who have previously responded to one drug may be more likely to respond to another. However, a greater proportion of patients with IBS-D who reported inadequate symptom control with loperamide noted a significant improvement in the symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea when treated with eluxadoline compared with placebo; those who reported inadequate control with loperamide were twice as likely to respond to eluxadoline than to placebo (27% vs. 12.7% P=0.001).

In addition, analysis of the component end points demonstrated that the stool consistency response rate was consistent with that of the composite end point, with patients reporting significant improvements in stool consistency with either dose of eluxadoline compared with placebo during the 12- or 26-week study period. For the end point of abdominal pain, there was a statistically superior pain response with eluxadoline 75 mg over placebo, with a treatment effect size of >10% over both the 12- and 26-week study periods. However, the 100 mg dose showed no significant difference for this end point compared with placebo. In those with prior adequate symptom control with loperamide, the pain results mirrored the full analysis reported by Lembo et al. (18), with no significant differences between eluxadoline and placebo at either dose level and a greater proportion of responders with placebo. Eluxadoline is therefore a treatment option in clinical practice for patients with IBS-D who experience inadequate symptom control with loperamide, and may significantly improve abdominal pain in this patient population at the dose of 75 mg.

These studies were not designed for direct comparison of the efficacy of eluxadoline with that of loperamide, especially with respect to long-term therapy, as only ∼14% of patients took loperamide chronically. The extent to which one agent works better than the other for the individual symptoms of diarrhea or abdominal pain, or a composite of both, remains unclear and no conclusions can be drawn with respect to comparison of the two agents. It is notable, however, that the small studies performed previously, evaluating the efficacy of loperamide for the treatment of IBS-D (20, 22), did not include the combined responder end point now required by the FDA (23). Direct comparison of the efficacy and safety of loperamide with that of eluxadoline in patients with IBS-D using up-to-date end points remains an important area for future investigation.

During the 12- and 26-week phase 3 studies, loperamide was available for study patients to use as a rescue medication; its use was less common in patients treated with eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg compared with those who received placebo (25.6% and 26.7% vs. 31.3%, respectively), and this may suggest superior treatment satisfaction with eluxadoline. Using imputed nonresponse when rescue loperamide was used, these analyses demonstrated that the use of rescue loperamide in the two phase 3 studies did not affect the composite responder rates with eluxadoline compared with placebo, and patients receiving eluxadoline 75 or 100 mg showed significantly higher responder rates than the placebo group (25.6% and 26.9% vs. 16.4%, respectively). The exact reasons for rescue loperamide use were not collected in these studies.

Safety findings with eluxadoline in patients who reported inadequate symptom control with loperamide were consistent with the findings from the overall phase 3 patient population (18) and the known safety profile of eluxadoline (B.D. Cash et al., unpublished data); over half of patients with inadequate symptom control with prior loperamide experienced AEs with eluxadoline, of which GI AEs (nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation) were the most frequent, although overall incidences were low. Of the patients who used rescue loperamide during the studies and reported GI AEs, over half reported ≥1 GI AE with an onset date after loperamide use. However, there was no clear temporal relationship between loperamide use and the occurrence of GI AEs. Constipation was more frequently reported in patients treated with eluxadoline compared with placebo, though the incidence was low and consistent with that from the overall phase 3 patient population (B.D. Cash et al., unpublished data).

The primary end point of these two large, prospective trials focused on efficacy and safety. Although data collection for the trials was prospective, the present study represents a subgroup of the initial study, with the inherent limitations of such an analysis. That said, the large sample size and the prospective nature of the analyses minimizes these limitations. Furthermore, although many of the study patients had used loperamide during the year before study initiation, over half of the patients had not, and past use of loperamide relied upon patient recollection that may be unreliable and cannot be confirmed. Indeed, the exact dose of loperamide used by patients who reported inadequate symptom control with prior loperamide remains unknown; therefore, a comparison of patients who reported inadequate symptom control with prior loperamide at one dose compared with another dose is not possible.

In conclusion, eluxadoline is a therapeutic agent with a unique mechanism of action approved for the treatment of IBS-D in both men and women. A large phase 2 study and two large, prospective phase 3 studies have demonstrated that eluxadoline can effectively treat simultaneous symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea in patients with IBS-D. The current analyses demonstrate that eluxadoline can effectively treat IBS-D symptoms in patients who report inadequate relief with prior loperamide as well as in those who report adequate relief with prior loperamide. In addition, patients who took loperamide as a rescue medication during blinded study participation had nearly identical response rates and did not exhibit a greater number of AEs as compared with the population overall. These findings are clinically relevant as they demonstrate to health-care providers that eluxadoline is an efficacious and safe treatment option for the majority of patients diagnosed with IBS-D, irrespective of prior treatment experience with loperamide.

Study Highlights

Acknowledgments

The authors met criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. We take full responsibility for the scope, direction, and content of the manuscript and have approved the submitted manuscript. We received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. We thank Tanja Torbica of Complete HealthVizion for editorial assistance in the drafting of the Methods and Results sections, and in the revision of the draft manuscript on the basis of detailed discussion and feedback from all the authors; this assistance was funded by Allergan plc.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: Planning and conducting the study: Leonard S. Dove and Paul S. Covington; collection and interpretation of data: Brian E. Lacy, William D. Chey, Brooks D. Cash, Anthony J. Lembo, Leonard S. Dove, and Paul S. Covington; drafting and revision of the manuscript: Brian E. Lacy, William D. Chey, Brooks D. Cash, Anthony J. Lembo, Leonard S. Dove, and Paul S. Covington. All authors approved the final draft of this manuscript for submission.

Financial support: These studies were supported by Furiex Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Allergan plc. The sponsor was responsible for study design and data analysis, in collaboration with all authors. The collection and interpretation of the study data and writing of the manuscript was carried out by the authors.

Potential competing interests: Brian E. Lacy has participated in advisory boards for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Forest Laboratories, a subsidiary of Allergan plc. William D. Chey has received grant support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Perrigo, Prometheus, and Nestlé. He has served as an advisor or consultant for Actavis, a subsidiary of Allergan plc, AstraZeneca, Astellas, Asubio, Ferring, Furiex, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Nestlé, Proctor & Gamble, Prometheus Laboratories, Salix, Sucampo, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Brooks D. Cash has served as an advisor, consultant, or speaker for Actavis, a subsidiary of Allergan plc, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Sucampo, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Anthony J. Lembo is a consultant for Forest Laboratories, a subsidiary of Allergan plc, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Prometheus. Leonard S. Dove and Paul S. Covington serve as scientific consultants for Allergan plc.

References

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA 2015;313:949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:712–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000;119:654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10:299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré P, Gray J, Lam S et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006;28:1726–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1262–79.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giagnoni G, Casiraghi L, Senini R et al. Loperamide: evidence of interaction with mu and delta opioid receptors. Life Sci 1983;33 (Suppl 1): 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppin H. Review: loperamide-a potent antidiarrhoeal drug with actions along the alimentary tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1987;1:179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1149–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109 (Suppl 1): S2–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD et al. Role of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Dig Dis Sci 1984;29:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration Lotronex. Highlights of prescribing information. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021107s016lbl.pdf2010. Accessed 5 May 2015.

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS Efficacy and safety of repeat treatment with rifaximin for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: results of the TARGET-3 study. American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 17–22 October 2014.

- Wade PR, Palmer JM, McKenney S et al. Modulation of gastrointestinal function by MuDelta, a mixed μ opioid receptor agonist/ μ opioid receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol 2012;167:1111–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration Viberzi. Highlights of prescribing information. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206940s000lbl.pdf2015. Accessed 5 October 2016.

- Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2016;374:242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovdenak N. Loperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1987;130:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: physicians' awareness and patients' experience. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:3715–3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavö B, Stenstam M, Nielsen AL. Loperamide in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome—a double-blind placebo controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1987;22:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry - Irritable Bowel Syndrome - Clinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/UCM205269.pdf2012. Accessed on 30 September 2016.