Abstract

Background

Health materials to promote health behaviors should be readable and generate favorable evaluations of the message. Processing fluency (the subjective experience of ease with which people process information) has been increasingly studied over the past decade. In this review, we explore effects and instantiations of processing fluency and discuss the implications for designing effective health materials. We searched seven online databases using “processing fluency” as the key word. In addition, we gathered relevant publications using reference snowballing. We included published records that were written in English and applicable to the design of health materials.

Results

We found 40 articles that were appropriate for inclusion. Various instantiations of fluency have a uniform effect on human judgment: fluently processed stimuli generate positive judgments (e.g., liking, confidence). Processing fluency is used to predict the effort needed for a given task; accordingly, it has an impact on willingness to undertake the task. Physical perceptual, lexical, syntactic, phonological, retrieval, and imagery fluency were found to be particularly relevant to the design of health materials.

Conclusions

Health-care professionals should consider the use of a perceptually fluent design, plain language, numeracy with an appropriate degree of precision, a limited number of key points, and concrete descriptions that make recipients imagine healthy behavior. Such fluently processed materials that are easy to read and understand have enhanced perspicuity and persuasiveness.

Keywords: Processing fluency, Health literacy, Health information, Health materials, Health education, Readability, Persuasiveness

Background

Health information is an important understanding resource for the general public: it enables them to engage in the management of their health condition and improve their well-being. In particular, written health information has a number of advantages, such as reusability, portability, and flexibility of delivery [1]; this information has a positive impact on the effectiveness of patient education [2]. However, a significant concern is that users may not obtain optimal benefits from health information because of their limited health literacy, i.e., the ability to comprehend the information and use it to make appropriate decisions about their health and health care [3]. Such resources as patient educational materials and public health information are often written at a readability level that is too high for most intended recipients [4]. In such cases, more information may cause target subjects to feel confused and powerless rather than empowered. Furthermore, health information needs to prioritize uninterested, resistant users as targets [5]. Accordingly, written health materials have to be readable and generate favorable evaluations of the message.

The study of processing fluency (PF) has become increasingly popular over the past decade. PF is defined as the inferred subjective ease with which new external information can be processed [6]. Studies have shown that fluently processed stimuli generate positive judgments (e.g., liking, confidence). For example, Song and Schwarz [7] demonstrated that with easily readable exercise instructions, participants were more willing to incorporate such exercises as part of their daily routines than when the instructions were difficult to read. Accordingly, researchers have considered PF in terms of readability as a generator of positive judgments. Sharing the implications of PF among health-care professionals would appear to be beneficial in producing effective health materials. Hitherto, however, no study has reviewed PF publications with respect to their potential application in writing health information.

The present review aimed to explore the implications for designing effective health materials from the perspective of PF. We conducted a systematic literature review to answer a research question: what instantiations of PF are applicable to the design of health materials? We suggested practical implications for designing health materials based on the results.

Methods

To identify relevant studies, we searched seven online databases using “processing fluency” as a key word. The search encompassed both databases with a medical orientation and those with a focus on social sciences: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, Communication Abstracts, Business Source Complete, and ERIC. The initial database search was conducted in early December 2015. The search yielded 538 articles published between 1980 and 2015. To assess their relevance, we applied a strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. For inclusion, records (journal articles, books and chapters) had to be published—either online or in print. We excluded all poster presentations and proceedings papers. Only records written in English were included. Regarding content, publications were deemed relevant and included when they explicitly discussed PF and when they generally had potential application to the design of health materials. We therefore excluded studies that used only priming manipulation, addressed only such topics as art and language learning.

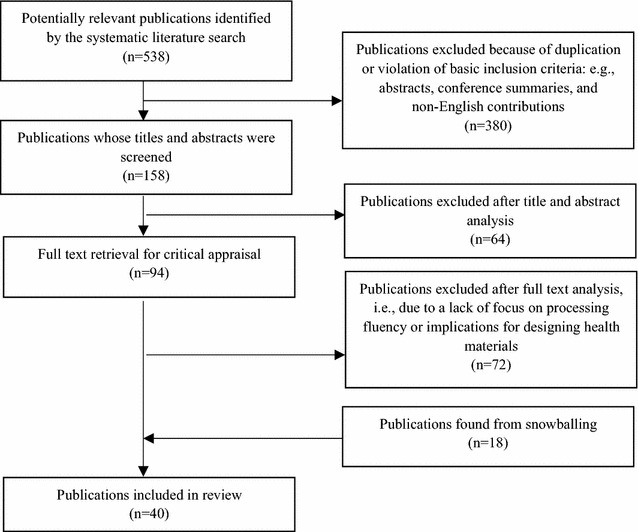

After the analysis of the titles and abstracts, we identified 94 unique publications as relevant. We subsequently analyzed the full text of each of the 94 articles. Following careful textual scrutiny, we excluded 72 publications due to a lack of focus on processing fluency or implications for designing health materials. We also gathered relevant publications using reference snowballing of the first 94 publications. After snowballing and full textual analysis, we added 18 articles. Thus, 40 articles were deemed fit for inclusion and subsequently review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the identified contributions

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 40 included articles, 30 were experimental studies; 10 were review articles. Table 1 summarizes the 30 experimental studies. Most of the studies were in the fields of psychology, marketing, or consumer research. Only five studies were related to health care.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental studies

| Reference | Materials | Fluency | Main outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song and Schwarz [7] | Exercise instruction sheets, recipe materials | Clear or unclear font | Estimates of time and skill needed, task fluency, willingness to do the task | Participants reported that the behavior would take more time, would feel less fluent, and would require more skill. Therefore, they were less willing to engage in it, when the instructions were printed in a dysfluent font |

| Reber et al. [10] | Drawings | Matching or non matching prime, back ground contrast, presentation duration | Prettiness judgments | Perceptual fluency increased liking and the experience of fluency was affectively positive |

| Begg et al. [11] | Statements | Known or unknown names of source, familiar or unfamiliar statements | Truth judgments | Truth judgments were influenced by source recollection and statement familiarity |

| McGlone and Tofighbakhsh [12] | Aphorisms | Rhymed or unrhymed | Truth judgments | Rhymed aphorisms were judged to be more accurate |

| Alter and Oppenheimer [13] | Currency | Familiar or unfamiliar | Purchasing power judgments | Familiar forms of currency were perceived to have greater purchasing power |

| Brown et al. [14] | Faces | Familiar or unfamiliar | Credibility judgments | Repeatedly encountered familiar faces were judged to be more credible |

| Song and Schwarz [15] | Names of ostensible food additives and amusement-park rides | Easy or difficult to pronounce | Safety judgments | Products were judged to be riskier when their names were difficult to pronounce |

| Dreisbach and Fischer [21] | Number words | Clear or unclear font, high or low background contrast | Response times and error frequencies | Low processing fluency was not only used for effort prediction but also for effort adjustments |

| Gmuer et al. [22] | Labels of wine | Clear or unclear font | Judgments of taste | Wine in a bottle with a fluent font label was preferred over the same wine in a bottle with a dysfluent label |

| Guenther [23] | Syllabus | Clear or unclear font | Forecasted grade and course difficulty | Participants forecasted higher grades and estimated the course as easier after reading the fluent syllabus |

| Reber and Schwarz [24] | Statements | High or low background contrast | Truth judgments | Highly visible statements were more often judged to be true |

| Mosteller [25] | Product information | Clear or unclear font, high or low background contrast, low or high information density | Cognitive effort, positive affect, choice satisfaction | Fluent information resulted in less cognitive effort perception, greater enjoyment and greater choice satisfaction |

| Oppenheimer [26] | Essays | Complex or simple words and sentences, clear or unclear font, high or low visibility | Acceptance decisions of the applicant, perceived author intelligence | Complexity and dysfluency led to negative evaluations |

| Lowrey [27] | Product advertisement | Simple or complex syntactic | Recall, attitudes toward the brand, level of involvement | Syntactic complexity affected recall and persuasiveness of advertising |

| Miller [28] | Financial reports | High or low readability | Trading activity | More readable financial disclosures were associated with greater trading activity |

| Rennekamp [29] | Financial reports | High or low readability | Stock valuations, management competence and trustworthiness | A fluent report generated stronger reactions to both good and bad news |

| Tan et al. [30] | Financial reports | High or low readability | Judgments on the firm’s future performance | High readability improved understanding of the firm’s performance |

| Laham et al. [31] | Names of individuals | Easy or difficult to pronounce | Judgments of liking, positions in the firm hierarchy | Those who had phonologically fluent names were liked more and occupied higher status positions in firms |

| Dohle and Siegrist [32] | Names of medications | Easy or difficult to pronounce | Judgments of safety, effectiveness, side effects, and willingness to buy | Phonologically fluent medications were judged to be safer and to have fewer side effects; greater willingness to buy |

| Manley et al. [33] | Recruitment sheets for a medical study | Easy or difficult to pronounce, clear or unclear font | Judgments of attractiveness, complexity, expected risk and required effort | Participants judged the study more complex when they read a dysfluent sheet |

| King and Janiszewski [35] | Numbers, advertisements with numbers | Numbers from common arithmetic problems or not | Judgments of liking, product choices | Participants preferred numbers from common arithmetic problems more than other numbers |

| Coulter and Roggeveen [36] | Prices | Numbers constitute an approximation sequence or not, Numbers are multiples of one another or not | Purchase intentions and judgments of liking | When the numbers constituted an approximation sequence or were multiples of one another, incidences of price promotion predilection increased |

| Schwarz et al. [37] | Assertive or unassertive behaviors | Easy or difficult to recall | Self-rating of assertiveness | Higher retrieval fluency of assertive behaviors led to higher self-rating of assertiveness |

| Rothman and Schwarz [38] | Risk factors for heart disease | Easy or difficult to recall | Vulnerability judgments | Higher retrieval fluency of risk-increasing factors led to higher vulnerability judgments |

| Chang [39] | Product information | Easy or difficult to recall | Quality and monetary sacrifice judgments | Higher retrieval fluency led to higher evaluation of product quality and to less focus on monetary sacrifice |

| Wånke et al. [40] | Product information | Easy or difficult to recall | Brand evaluations | Higher retrieval fluency led to higher brand evaluation |

| Wänke and Bless [41] | Advertisements | Easy or difficult to recall | Product evaluations | Higher retrieval fluency led to higher product evaluation |

| Petrova and Cialdini [42] | Advertisements | To image or not | Brand attitudes and purchase intentions | Service was preferred more when the participants vividly imagined it |

| Mandel et al. [43] | Story | Plausible or implausible | Predicted future income | Participants who read a plausible success story judged they themselves can success more in future |

| Gregory et al. [44] | Service solicitation | To image or to be explained | Contract ratios | Subjects who imagined the benefits of a service were more likely to subscribe to the service than subjects who were merely given information |

Nature of PF and its effects

Every cognitive task, such as reading health materials, can be described along a continuum from effortless to highly effortful. This cognitive effort produces a corresponding metacognitive experience, which ranges from fluent to disfluent. Human judgment is influenced not only by the information content but also by the metacognitive experience of processing that information [8, 9]. For example, health materials that are written with familiar, simple words are easy to read and understand, and therefore assumed to be fluently processed, i.e., they possess lexical fluency. In contrast, materials that include a number of unfamiliar jargon terms are hard to read and understand, and therefore assumed to be disfluently processed. There are various types of fluency, as discussed below (e.g., syntactic, phonological, and retrieval fluency; for a review, see [6]); however, their effect on judgment is uniform: fluently processed stimuli generate a positive judgment among recipients [6]. More precisely, compared with less fluent stimuli, fluently processed stimuli are generally rated as follows: more pleasing [10]; more trustworthy [11, 12]; more valuable [13]; more honest and sincere [14]; and safer [15]. Fluently processed stimuli also have numerous other favorable attributes (for reviews, see [6, 16]). The manner in which the PF effect works has been explained by the hedonic marking hypothesis [10, 17], attributional accounts [18], and naive theories [19]. Recent studies have focused largely on naive theories to account for context-specific interpretations of the PF effect (for reviews, see [16, 19]).

Processing fluency also influences a recipient’s willingness to undertake a given task. The experience of fluent processing has been repeatedly demonstrated to serve as an affective signal. In general, high PF generates a positive affect, whereas low PF produces a negative affect [17]. The positive affect is a source of positive attitude, which is an antecedent to behavioral intention [20].

Processing fluency is used to predict the effort necessary for a given task; accordingly, it has an impact on willingness to do a task (discussed below) [21]. More precisely, low PF serves as an aversive signal and reduces willingness to engage in the given task [21]. For example, health materials that are presented in a small, hard-to-read font and use jargon terms and complex syntax cannot be processed fluently. Consequently, readers will suppose that greater effort is needed for the given task and are more likely to resist the health message—partly because of disfluency. The reverse also applies.

Instantiations of PF

There are various instantiations of fluency (for a review, see [6]); however, the present review focuses on perceptual, lexical, syntactic, phonological, retrieval, and imagery fluency because these are particularly relevant in the design of health materials. We present instantiations of PF with experimental studies and then address their implications in designing health materials in the “Discussion”.

Physical perceptual fluency

The subjective ease with which stimuli are physically perceived (e.g., a clear or unclear font and the contrast between lettering and the background) is termed physical perceptual fluency [6]. Font manipulation is a common method that has been used to investigate the fluency effect. Gmuer et al. [22], for example, demonstrated that a label’s PF influenced taste evaluations: wine in a bottle with a label printed in a fluent font (Arial Narrow) was liked more than wine labeled with a disfluent font (Mistral) despite the fact that both the wine and label descriptions were identical. This study is an apt example of fluently processed materials’ effect of increasing judgments of liking.

A study by Song and Schwarz [7] has particularly strong implications for designing health materials. Participants were asked to read identical instructions for an exercise printed in an easy-to-read (12-point Arial) or difficult-to-read (12-point Brush) font. As predicted, they estimated that the exercise would take less time and felt quicker and more fluid when the font was easy to read than when it was difficult. Accordingly, participants also indicated greater willingness to make the exercise part of their daily routine when the font was easy to read.

A similar effect was obtained in a study using the syllabus of an undergraduate college course [23]. Participants read an identical summary syllabus printed in an easy-to-read (12-point Arial) or difficult-to-read (12-point Brush) font. As anticipated, participants believed they would receive higher grades and that the course would be easier when they read the more fluent font.

These two studies support experienced fluency of written materials as a subjective indicator of the effort needed for a particular task. If materials are easy to read and fluently processed, the perception of the required effort decreases and recipients may have a greater willingness to undertake the task [21].

Variations in the contrast between the text and background are also frequently used in fluency research. In a classic study by Reber and Schwarz [24], statements of the form “Town A is in country B” (e.g., Osorno is in Chile) were presented at the center of a computer screen. Half of the statements were true, and half were untrue. The visibility of the statements was manipulated by contrasting the colors against the white background. Highly visible colors included blue and red; moderately visible colors included green, yellow, and light blue. The participants judged the highly visible statements as being more probably true than statements with low visibility.

A recent study manipulated the font, background contrast, and information density on a fictitious online shopping Web site [25]. The product information appeared in Arial or Mistral font, with a white or gray background against black text; five or 15 attributes were presented for each alternative on fluent and disfluent pages. Fluently processed pages resulted in less cognitive effort perception, greater enjoyment of the task, and consequently greater choice satisfaction among participants.

In sum, high perceptual fluency (e.g., using an easily legible font with high background contrast) increases the likelihood of positive judgments and enhances recipients’ willingness to do a given task.

Lexical, syntactic, and phonological fluency

The subjective ease with which words are processed is termed lexical fluency; the subjective ease of parsing grammatical constructions is termed syntactic fluency; and the subjective ease of pronunciation is termed phonological fluency [6]. Collectively, these are referred to as linguistic fluency [6].

In general, highly readable materials are lexically and syntactically fluently processed; consequently, they generate more favorable evaluations of the message [26, 27]. Miller [28] measured the readability of financial reports of firms using readability measures. The results showed that more readable financial disclosures were associated with greater trading activity among small investors. Along similar lines, Rennekamp [29] adapted financial disclosure materials from those of a real company. Rennekamp created more readable and less readable versions of a financial report by manipulating such factors as sentence length, simplicity of terms, and ease of syntax. After reading the fluent or disfluent financial reports, participants were asked to estimate the appropriate common stock valuation, management competence, and trustworthiness of the firm. The fluent report generated stronger reactions: judgments were more positive to good news and more negative to bad news. Additionally, participants were more likely to feel they could trust a fluent report. A similar result is reported by Tan et al. [30]. Thus, highly readable materials generate more favorable evaluations and stronger reactions.

The phonological ease of words also influences our judgments. Certain letter strings are easier to process than others. For example, English speakers cannot naturally pronounce the string “SBG” (disfluent), whereas they can easily pronounce the equally nonsensical “SUG” (fluent). Laham et al. [31] showed that people form more positive impressions of easily pronounceable names and their bearers (e.g., Mr. Smith vs. Mr. Colquhoun). They further revealed that people with easily pronounceable names occupied higher-status positions in firms. Dohle and Siegrist [32] found that easily pronounceable medications were perceived to be safer and have fewer side effects, and participants expressed greater willingness to buy them than medications that were difficult to pronounce. Thus, phonologically fluent words generate favorable evaluations [33].

Round numbers are also processed with linguistic fluency. Such round numbers as 10, 25, and 100 are frequently used because they can express approximate quantities and therefore refer to an entire range of magnitudes [34]. For example, one might refer to any given number within the range 90–110 (e.g., 93, 99, 102, and 106) as “about 100.” Accordingly, the number 100 is used more frequently and processed more fluently than those other numbers, leading to greater liking [34, 35]. Coulter and Roggeveen [36] investigated whether numbers that were members of a base-10 approximation sequence were preferred in a shopping context. The authors showed that prices and discount amounts that were members of an approximation sequence (e.g., $100, $30, $70, and 70% discount) generated greater liking and purchase intentions than did precise prices and discount amounts (e.g., $101, $29, $72, and 71%). Thus, round numbers generate more positive judgments.

Retrieval fluency

The subjective ease with which individuals recall information or retrieve arguments relevant to a message is termed retrieval fluency [6]. Although the assumption of retrieval fluency has enjoyed great popularity since Tversky and Kahneman [8] introduced availability heuristic, it was not adequately tested before the 1990s [37]. Rothman and Schwarz [38] asked participants to recall either three or eight behaviors that could increase or decrease their risk for heart disease. Although recalling three risk factors was relatively easy, recalling eight risk factors was difficult. Participants without a family history of heart disease reported lower vulnerability after recalling eight rather than three risk-increasing behaviors and higher vulnerability after recalling eight rather than three risk-decreasing behaviors. They presumably used a heuristic judgment strategy that relied on the ease of recall: if it is easy (difficult) to recall, it is likely (unlikely) to occur. In a similar vein, information that is easy to retrieve has been demonstrated to increase the favorable evaluation of a product [39, 40] as well as the persuasiveness of an argument [41].

Imagery fluency

The subjective ease with which one can imagine hypothetical scenarios that have not yet occurred is termed imagery fluency [6]. Brand attitudes and purchase intentions become increasingly positive when individuals can vividly imagine the product [42]. Business school students were able to imagine success more easily and judge that they themselves were more likely to succeed in the future when they read a story about a plausible (rather than implausible) level of success [43]. Gregory et al. [44] showed that subjects who imagined themselves enjoying the benefits of a cable TV service were more likely to subscribe to the service than subjects who were merely given information about the service. Thus, self-generated images of future behavior and events have an effect on subsequent judgments and behavior.

Discussion

Studies have shown that evaluating information and making decisions depend not only on the presented information itself but also on the information’s PF. As described in this review, high PF of information generates positive judgment among recipients. The implications of this cast new light on the importance of designing readable health materials. Traditionally, health materials have been difficult to process because of excessive jargon [45, 46], excessively high reading levels [4], and dense presentation of information [47, 48]. In recent years, low health literacy has been recognized as one of the barriers to understanding and using health information in making appropriate decisions about one’s health and health care [3]. It is also recognized that health literacy is a result of interactions between an individual’s skill and the demands of the society in which the individual lives, including the manner in which health information is communicated [49]. Accordingly, in recent years, efforts to make health information easy to read have become recognized as more important. However, relevant efforts in health care have focused on lowering the barriers to health information for those with low literacy skills. In contrast, as indicated in this review, fluency research has the active goal of focusing on increasing positive judgments and enhancing behavioral willingness. Studies of PF indicate that easiness to read, recall and imagine (i.e., high PF) can contribute to enhancing both the perspicuity and persuasiveness of health materials.

Based on this review, we suggest five practical implications for designing effective health materials that generate positive judgment and enhance recipients’ willingness to follow healthy behavior.

Design materials with readability: physical perceptual fluency

Assessment tools for written materials propose guidelines regarding fonts and type size to make materials easy to read [50, 51]. Doak et al. [50] states that type size and fonts can make text easy or difficult for readers at all skill levels, and they recommend that text be in a serif font in 12 point or larger. That study also recommends a good contrast between the text and background [50]. As indicated in the “Results” section, high physical perceptual fluency (e.g., an easily legible font with high background contrast) increases positive judgments and enhances recipients’ willingness to do a given task [7, 21–25]. Health materials should be designed with perceptual fluency to generate positive judgments among recipients.

Use of plain language: linguistic fluency

Without exception, assessment tools and guidelines for health materials emphasis the importance of plain language; i.e., using common and familiar words, short sentences, and explicit sentence constructions, so that readers can process the information more easily and quickly [50, 52–55]. As shown in the “Results” section, phonologically fluent (i.e., easy to pronounce) words generate favorable evaluations [31–33]. Furthermore, highly readable materials that are written with plain language generate more favorable evaluations, greater trust and stronger reactions [26–30]. Although these PF studies were in contexts other than health, health materials also should generate favorable evaluations and trust, as well as strong reactions from their recipients, especially in emotional appeals [56]. Favorableness, trust and strong reaction are sources of persuasiveness [57]. Using plain language that is linguistically fluently processed is considered to be important not only for making written health materials comprehensible but also for enhancing persuasiveness of those materials.

Use round numbers: linguistic fluency

Numerical precision is needed for analysis and reporting in a scientific research context. However, unnecessary numerical precision is undesirable and can be misleading to laypeople, such as patients. Ehrenberg [58] points out that recipients can deal effectively only with numbers that contain no more than two significant digits. Assessment instruments for written materials therefore recommend the deletion of unnecessary numbers and suggest that when numbers are used, they should be clear and easy to understand [53, 54]. As indicated in the “Results” section, round numbers generate more positive judgment than precise numbers [34–36]. Lang and Secic [59] recommend that numbers in health materials should be rounded unless greater precision is actually necessary—and then reported with the appropriate degree of precision.

Limit number of key points: retrieval fluency

It is widely accepted that there is a general limit on human cognitive capacity [60]. Humans are “cognitive misers” [61] and conserve cognitive resources. Thus, people attempt to minimize the cognitive workload according to the law of least mental effort [62]. Accordingly, when patients or caregivers are overwhelmed with too much health information, their ability to comprehend, recall, and use this information can decline [63]. Nevertheless, written health materials tend to be information dense [47, 48]. Kaphingst et al. [48] reviewed health materials and found that only half limited the number of key points to five or fewer per section. When health materials are information dense, recipients generally have difficulty in memorizing them and recalling the content. As demonstrated in the “Results” section, the ease of recall of information influences judgment [37–41]. Furthermore, memory is an antecedent of behavior: information has to be memorized and recalled if a recipient is to perform the health behavior indicated [64]. Accordingly, as Brega et al. [55] suggest, health-care professionals should prioritize what needs to be discussed and limit information to three to five key points so that the content may be easily processed and recalled.

Make recipients imagine health behavior: imagery fluency

As shown in the “Results” section, self-generated images of future behavior and events influences subsequent judgments and behavior [42–44]. One of the purported reasons for the imagery fluency effect is that it makes images of relevant behavior subsequently more available in memory and consequently makes them appear more probable [8, 65]. Image generation and memorability are prompted by concrete descriptions [66]. As Shoemaker et al. [53] recommend, health behavior described in health materials should be broken down into manageable, explicit steps and portrayed concretely. In this way, recipients can easily imagine the behavior, which will help them do likewise.

Limitations

Although the findings described in this review provide a promising starting point for further research into the PF effect in a health-care context, some limitations should be considered. It may be assumed that we retrieved the most important contributions dealing with PF using our strategy of combining a database search with an extensive manual search; however, we may still have missed some publications. In addition, most of the contributions detected in the search were studies in areas other than health. The applicability of findings from outside health care to a health-care context deserves careful consideration. Future studies need to investigate the fluency effect in the health-care context. Furthermore, some recent studies have focused on moderating variables of the PF effect, such as construal level and need for cognition [67–69]. Additionally, recent studies have investigated the cases in which processing disfluency was efficacious [70–73]. These should be noted and explored to better our understanding of the PF effect.

Conclusions

When health-care professionals design health materials, they should consider perceptually fluent design, plain language, numeracy with the appropriate degree of precision, a limited number of key points, and concrete descriptions so that recipients may imaging the health behaviors. Doing so will lower the literacy level of health materials and generate positive judgments, and it may enhance recipients’ willingness to perform healthy behavior. If we design health materials to be processed more fluently, we will be able to motivate recipients more effectively.

Authors’ contributions

TO and HI conceived and designed the study. TO conducted the literature searches. TO and HI wrote the manuscript. MO, MK, and TK participated in interpreting the results and writing the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant (Number 167100000384).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviation

- PF

processing fluency

Contributor Information

Tsuyoshi Okuhara, Phone: +81-3-5800-6549, Email: okuhara-ctr@umin.ac.jp.

Hirono Ishikawa, Email: hirono-tky@umin.ac.jp.

Masahumi Okada, Email: sokada-tuk@umin.ac.jp.

Mio Kato, Email: mkato-ctr@umin.ac.jp.

Takahiro Kiuchi, Email: tak-kiuchi@umin.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Bernier M. Developing and evaluating printed education materials: a prescriptive model for quality. Orthop Nurs. 1993;12:39–46. doi: 10.1097/00006416-199311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theis S, Johnson J. Strategies for teaching patients: a meta-analysis. Clin Nurse Specialist. 1995;9:100–120. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A, Kindig D. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd RE, Moeykens BA, Colton TC. Health and literacy: a review of medical and public health literature. In: Comings JP, Garner B, Smith C, editors. The annual review of adult learning and literacy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. pp. 158–199. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkin C, Salmon C. Persuasive strategies in health campaigns. In: Dillard JP, Shen L, editors. The SAGE handbook of persuasion: developments in theory and practice. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2013. pp. 278–295. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter AM, Oppenheimer DM. Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2009;13:219–235. doi: 10.1177/1088868309341564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song H, Schwarz N. If it’s hard to read, it’s hard to do: processing fluency affects effort prediction and motivation. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(10):986–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn Psychol. 1973;5:207–232. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flavell J. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am Psychol. 1979;34:906–911. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reber R, Winkielman P, Schwarz N. Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychol Sci. 1998;9:45–48. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begg IM, Anas A, Farinacci S. Dissociation of processes in belief: source recollection, statement familiarity, and the illusion of truth. J Exp Psychol: General. 1992;121:446–458. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.121.4.446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGlone MS, Tofighbakhsh J. Birds of a feather flock conjointly (?): rhyme as reason in aphorisms. Psychol Sci. 2000;11:424–428. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alter AM, Oppenheimer DM. Easy on the mind, easy on the wallet: the roles of familiarity and processing fluency in valuation judgments. Psychon Bull Rev. 2008;15:985–990. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.5.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown AS, Brown LA, Zoccoli SL. Repetition-based credibility enhancement of unfamiliar faces. Am J Psychol. 2002;115:199–209. doi: 10.2307/1423435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song H, Schwarz N. If it’s difficult to pronounce, it must be risky. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reber R, Schwarz N, Winkielman P. Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8:364–382. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkielman P, Schwarz N, Fazendeiro TA, Reber R. The hedonic marking of processing fluency: implications for evaluative judgment. In: Musch J, Klauer KC, editors. The psychology of evaluation: affective processes in cognition and emotion. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unkelbach C, Greifeneder RA. General model of fluency effects in judgment and decision making. In: Unkelbach C, Greifeneder R, editors. The experience of thinking. London: Psychology Press; 2013. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwarz N. Metacognitive experiences in consumer judgment and decision making. J Consum Psychol. 2004;14:332–348. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1404_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eagly AH, Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreisbach G, Fischer R. If it’s hard to read… try harder! Processing fluency as signal for effort adjustments. Psychol Res. 2011;75:376–383. doi: 10.1007/s00426-010-0319-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gmuer A, Siegrist M, Dohle S. Does wine label processing fluency influence wine hedonics? Food Qual Prefer. 2015;44:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guenther R. Does the processing fluency of a syllabus affect the forecasted grade and course difficulty? Psychol Rep. 2012;110:946–954. doi: 10.2466/01.11.28.PR0.110.3.946-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reber R, Schwarz N. Effects of perceptual fluency on judgments of truth. Conscious Cogn. 1999;8:338–342. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1999.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosteller J, Donthu N, Eroglu S. The fluent online shopping experience. J Bus Res. 2014;67:2486–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oppenheimer DM. Consequences of erudite vernacular utilized irrespective of necessity: problems with using long words needlessly. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2006;20:139–156. doi: 10.1002/acp.1178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowrey TM. The effects of syntactic complexity on advertising persuasiveness. J Consum Psychol. 1998;7:187–206. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller B. The effects of reporting complexity on small and large investor trading. Account Rev. 2010;85:2107–2143. doi: 10.2308/accr.00000001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rennekamp K. Processing fluency and investors’ reactions to disclosure readability. J Account Res. 2012;50:1319–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-679X.2012.00460.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan HT, Wang EY, Zhou B. How does readability influence investors’ judgments? Consistency of benchmark performance matters. Account Rev. 2014;90:371–393. doi: 10.2308/accr-50857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laham S, Koval P, Alter AM. The name-pronunciation effect: why people like Mr. Smith more than Mr. Colquhoun. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48:752–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dohle S, Siegrist M. On simple names and complex diseases: processing fluency, not representativeness, influences evaluation of medications. Adv Consum Res. 2011;39:451–452. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manley A, Lavender T, Smith D. Processing fluency effects: can the content and presentation of participant information sheets influence recruitment and participation for an antenatal intervention? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jansen C, Pollmann M. On round numbers: pragmatic aspects of numerical expressions. J Quant Linguist. 2001;8:187–201. doi: 10.1076/jqul.8.3.187.4095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King D, Janiszewski C. The sources and consequences of the fluent processing of numbers. J Mark Res. 2011;48:327–341. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.48.2.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coulter K, Roggeveen A. Price number relationships and deal processing fluency: the effects of approximation sequences and number multiples. J Mark Res. 2014;51:69–82. doi: 10.1509/jmr.12.0438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarz N, Bless H, Strack F, Klumpp G, Rittenauer-Schatka H, Simons A. Ease of retrieval as information: another look at the availability heuristic. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1991;61:195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothman A, Schwarz N. Constructing perceptions of vulnerability: personal relevance and the use of experiential information in health judgments. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1998;24:1053–1064. doi: 10.1177/01461672982410003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang CJ. Price or quality? The influence of fluency on the dual role of price. Mark Lett. 2013;24:369–380. doi: 10.1007/s11002-013-9223-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wånke M, Gerd B, Andreas J. There are many reasons to drive a BMW: does imagined ease of argument generation influence attitudes? J Consum Res. 1997;24:170–178. doi: 10.1086/209502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wänke M, Bless H. The effects of subjective ease of retrieval on attitudinal judgments: the moderating role of processing motivation. In: Bless H, Forgas JP, editors. The message within: the role of subjective experience in social cognition and behavior. New York: Psychology Press; 2000. pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrova PK, Cialdini RB. Fluency of consumption imagery and the backfire effects of imagery appeals. J Consum Res. 2005;32:442–452. doi: 10.1086/497556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandel N, Petrova PK, Cialdini RB. Images of success and the preference for luxury brands. J Consum Psychol. 2006;16:57–69. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1601_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gregory WL, Cialdini RB, Carpenter KM. Self-relevant scenarios as mediators of likelihood estimates and compliance: does imagining make it so? J Personal Soc Psychol. 1982;43:89–99. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.1.89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byrne TJ, Edeani D. Knowledge of medical terminology among hospital patients. Nurs Res. 1984;33:178–181. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castro CM, Wilson C, Wang F, Schillinger D. Babel babble: physicians’ use of unclarified medical jargon with patients. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):85–95. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Randolph W, Viswanath K. Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: marketing health in a crowded media world. Ann Rev Public Health. 2004;25:419–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaphingst KA, Kreuter MW, Casey C, Leme L, Thompson T, Cheng MR, et al. Health literacy index: development, reliability, and validity of a new tool for evaluating the health literacy demands of health information materials. J Health Commun. 2012;17:203–221. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Health Literacy. Measures of health literacy: workshop summary. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 50.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moody C, Rose M. Literacy and health: defining links and developing partnerships. A final report to population health. Winnipeg: Literacy Partners of Manitoba; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudd R, Kaphingst K, Colton T, Gregoire J, Hyde J. Rewriting public health information in plain language. J Health Commun. 2004;9:195–206. doi: 10.1080/10810730490447039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. The patient education materials assessment Tool (PEMAT) and user’s guide. AHRQ Publication No. 14-0002-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). Clear Communication Index. http://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/. Accessed 2 Dec 2015.

- 55.Brega AG, Barnard J, Mabachi NM, Weiss BD, DeWalt DA, Brach C, et al. AHRQ health literacy universal precautions toolkit. 2. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner MM. Using emotional appeals in health messages. In: Cho H, editor. Health communication message design: theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2012. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pratkanis A. Social influence analysis: An index of tactics. In: Pratkanis A, editor. The science of social influence: advances and future progress. New York: Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 17–82. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ehrenberg A. The problem of numeracy. Am Stat. 1981;35:67. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lang TA, Secic M. How to report statistics in medicine: annotated guidelines for authors, editors, and reviewers. 2. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2006. pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kahneman D. Attention and effort. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor SE. The interface of cognitive and social psychology. In: Harvey JH, editor. Cognition, social behavior, and the environment. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kool W, McGuire JT, Rosen ZB, Botvinick MM. Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. J Exp Psychol: General. 2010;139:665–682. doi: 10.1037/a0020198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGuire WJ. Attitudes and attitude change. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of social psychology. New York: Random House; 1985. pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carroll JS. The effect of imagining an event on expectations for the event: an interpretation in terms of the availability heuristic. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1978;14:88–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(78)90062-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark JM, Paivio A. Dual coding theory and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 1991;3:149–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01320076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L. How effective are your CSR messages? The moderating role of processing fluency and construal level. Int J Hosp Manag. 2014;41:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miele D, Molden D. Naive theories of intelligence and the role of processing fluency in perceived comprehension. J Exp Psychol: General. 2010;139:535–557. doi: 10.1037/a0019745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cho H, Schwarz N. If I don’t understand it, it must be new: processing fluency and perceived product innovativeness. Adv Consum Res. 2006;33:319–320. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson DV, Ince EC. When disfluency signals competence: the effect of processing difficulty on perceptions of service agents. J Mark Res. 2013;50:228–240. doi: 10.1509/jmr.11.0340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nielsen JH, Escalas JE. Easier is not always better: the moderating role of processing type on preference fluency. J Consum Psychol. 2010;20:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alter AL, Oppenheimer DM, Epley N, Eyre RN. Overcoming intuition: metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. J Exp Psychol: General. 2007;136:569. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alter AL. The benefits of cognitive disfluency. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:437–442. doi: 10.1177/0963721413498894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]