Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

We previously reported that combination of mean lung dose (MLD), and inflammatory cytokines (IL-8 and TGF-β1) may provide a more accurate model for radiation-induced lung toxicity (RILT) prediction in 58 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study is to validate the previous findings with new patients and explore new models with more cytokines.

Materials/Methods

142 patients with stage I–III NSCLC treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) from prospective studies were included. Sixty-five new patients were used to validate previous findings, and all 142 patients to explore new models. Thirty inflammatory cytokines were measured in plasma samples before RT, 2 weeks and 4 weeks during RT (pre, 2w, 4w). Grade ≥2 RILT defined as grade 2 and higher radiation pneumonitis or symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis was the primary endpoint. Logistic regression was performed to evaluate the risk factors of RILT. The area under the curve (AUC) for the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves was used for model assessment.

Results

Sixteen of 65 patients (24.6%) developed RILT2. Lower pre IL-8 and higher TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio were associated with higher risk of RILT2. The AUC increased to 0.73 by combining MLD, pre IL-8 and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio compared with 0.61 by MLD alone to predict RILT. In all 142 patients, 29 patients (20.4%) developed grade ≥2 RILT. Among the 30 cytokines measured, only IL-8 and TGF-β1 were significantly associated with the risk of RILT2. MLD, pre IL-8 level and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio were included in the final predictive model. The AUC increased to 0.76 by combining MLD, pre IL-8 and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio compared with 0.62 by MLD alone.

Conclusions

We validated that a combination of mean lung dose, pre IL-8 level and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio provided a more accurate model to predict the risk of RILT2 compared to MLD alone.

Keywords: Lung neoplasm, Non-small cell lung cancer, radiation induced lung toxicity, Cytokines

Introduction

Radiation induced lung toxicity (RILT) is one of the dose-limiting toxicities for radiotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Dosimetric factors especially mean lung dose (MLD) have been consistently correlated with the risk of RILT [1, 2]. Other factors, such as older age, pre-existing interstitial lung disease, tumor located in lower lung and concurrent taxane chemotherapy, have been shown to be associated with RILT [3]. Inflammatory cytokines play important roles in the biological processes of radiation lung damage, damage repair and clinical toxicity. We have previously reported in 58 patients that IL-8 and TGFβ1 were important predictors for RILT [4].

We hypothesized that 1) the model of combined MLD, IL-8, and TGFβ1 can predict RILT in an independent dataset, and 2) adding other inflammatory cytokines in a larger sample size can identify an improved model to predict RILT. The population from the same prospective studies in the same institutions as the initial finding was used for validation and new model exploration.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population included 142 patients with newly diagnosed stage I–III NSCLC, consecutively enrolled in the following prospective studies from 2 medical centers during 2004~2012: a phase 1/2 study of radiation dose escalation (limited to a lung normal tissue complication probability [NTCP] value of < 15%) with concurrent chemotherapy; 2 consecutive studies using functional imaging and biomarkers to assess patient outcome; and a study using midtreatment PET to guide individualized dose escalation. The studies were Institutional Review Board-approved. All 142 patients had 30 cytokines measured throughout the course of radiation therapy for exploring new models. The first 58 patients were included in the previously report, the remaining patients were used for validation study. Nineteen patients with unachievable MLD data were excluded in validation study but included for new model exploration for potentially significant cytokines. The remaining 65 patients formed the validation group.

Radiotherapy was given by using a three-dimensional conformal technique. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was used in only a few challenging cases. A median total physical dose of 70 Gy (range, 44–87.9Gy) was delivered with 2.0–2.9 Gy daily fractions over 4–7 weeks using 6–16 MV photons. In general, the prescribed dose covered 95% of the planning target volume (PTV), and was limited by tolerance limits of normal tissue. The lungs were defined as inclusion of both lungs and exclusion of the gross tumor volume.

RILT evaluation

All patients were prospectively evaluated weekly during RT, with follow-up evaluation at 1 month after completion of RT, and then every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the second year. At each follow-up, patients underwent a history review and physical examination as well as a chest computed tomography scan. Adverse events other than RILT were evaluated and graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0. Patients with adverse events unavailable were excluded from this analysis. Grade ≥2 RILT, defined as grade 2 and higher radiation pneumonitis or symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis, was the primary endpoint. Considering CTCAE3.0 did not specify radiation related toxicity, radiation pneumonitis and clinical fibrosis were separately diagnosed and graded prospectively according to a previously defined system[5].

Specimen and assay

Serial blood samples were collected with K2EDTA (dikalium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) as the anticoagulant within a week prior to RT (pre) and at 2 weeks (2w, after 9–11 treatments) and 4 weeks during RT. Blood samples were placed on ice immediately after collection, centrifuged within 6 hours of collection at 3000g for 30 min (4°C), and supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C before use.

Measurements of 30 cytokines were performed in these platelet-poor plasma samples. A commercial Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel kit (MILLIPLEX® MAP, Cat. # HCYTMAG-60K-PX29 (premixed); Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to measure the levels of 29 cytokines, including EGF, Eotaxin, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-10, IL-12P40, IL-12P70, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-1RA, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, sCD40L, TGF-α, TNFα, VEGF. While TGF-β1 level was measured by molecule-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Human TGFβ1 DuoSet kit, R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN). All sample tests were run in duplicate, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

In validation section, logistic regression was used to test the significance of IL-8, TGFβ1 and MLD for inclusion in the model. The area under the curve (AUC) for the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were evaluated for the model. In new model exploration sections, univariate logistic regression was used to individually test cytokines and clinical factors for inclusion in the model. Stepwise selection was used to select significant predictors of RILT, including clinical factors, MLD, the absolute cytokine levels (pre, 2w, 4w) and ratios at 2 and 4 weeks to baseline (2w/pre and 4w/pre). A final model was decided upon the results from the stepwise selection procedure as well as the likelihood ratio test (LRT). All cytokine levels were log-transformed for use in linear logistic models due to the skewedness of the cytokine levels in the data. The area under the curve (AUC) for the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were evaluated for the model. For the multifactor model, AUC was calculated with the validation data based on the formula from the initial model [4].

Results

The study population consisted of 142 patients with adverse events and cytokines available, including 58 patients reported previously [4]. A total of 65 new patients in had complete information of MLD and were used for validation. Table 1 shows the baseline patient and treatment related characteristics of the 65 validation patients and 142 total patients. The performance status was 0–2. Carboplatin and paciltaxol were the main regimen used for concurrent chemotherapy.

Table 1.

The baseline patient and treatment related characteristics

| Variables | N (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Validation group (N=65) | Whole group (n=142) | |

| Age (year) | ||

| median | 65 | 67 |

| Interquartile range | 59–73 | 60–74 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 50 (76.9) | 108 (76.1) |

| Female | 15 (23.1) | 34 (23.9) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Current | 35 (54.5) | 57 (46.3) |

| Former | 25 (40.3) | 62 (50.4) |

| Never | 2 (3.2) | 4 (3.3) |

| COPD | ||

| Yes | 25 (38.5) | 55 (38.7) |

| No | 40 (61.5) | 87 (61.3) |

| Stage | ||

| I–II | 16 (24.6) | 42 (29.6) |

| III | 49 (75.4) | 100 (70.4) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 45 (69.2) | 86 (60.6) |

| No | 19 (29.2) | 44 (30.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.5) | 12 (8.5) |

| RT dose (BED10, Gy) | ||

| Median | 94 | 85.8 |

| Interquartile range | 84–110 | 60–74 |

| Mean lung dose (Gy) | ||

| median | 17 | 16.9 |

| Interquartile range | 12.8–19.9 | 12.7–20.1 |

Validation

Of the 65 new patients, 16 patients (24.6%) developed grade ≥2 RILT.

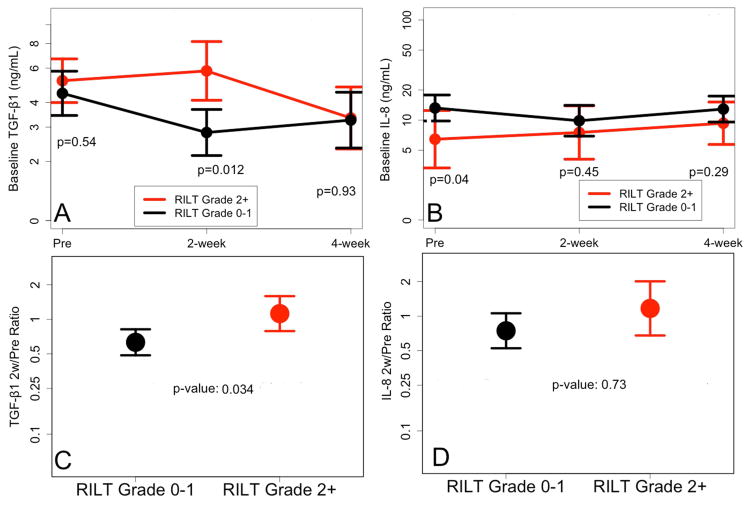

Variables listed in Table 1 were evaluated for their association with the risk of RILT, with age, RT dose and MLD as continuous variables. None was associated with RILT2 (p>0.05), e.g. the p value of MLD was 0.46 (OR 10.7, 95% CI: 0.31, 3.74). The association of IL-8 and TGF-β1 levels with the risk of RILT was shown in Table 2. Lower baseline level of IL-8 was associated with higher risk of RILT2 (Figure 1). Higher TGF-β1 level at 2w during RT or higher TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio were associated with higher risk of RILT2 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

The association of IL-8 and TGF-β1 levels with the risk of RILT in 65 patients. Mean and standard deviation are obtained by calculating mean and standard deviation of long-transformed cytokine levels and ratios and then applying anti-log (exponentiation) to those values.

| Mean±sd (pg/ml) | OR 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre IL-8 | 11.1±3.2 | 0.62 (0.39, 0.99) | 0.045 |

| 2w IL-8 | 9.2±3.5 | 0.84 (0.55, 1.31) | 0.45 |

| 4w IL-8 | 11.8±2.9 | 0.75 (0.45, 1.27) | 0.28 |

| IL-8 2w/pre ratio | 0.8±3.4 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.73 |

| IL-8 4w/pre ratio | 1.1±2.9 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.69 |

| Pre TGF-β1 | 4.6±2.3 | 1.24 (0.62, 2.47) | 0.54 |

| 2w TGF-β1 | 3.4±2.6 | 2.61 (1.23, 5.52) | 0.012 |

| 4w TGF-β1 | 3.3±2.7 | 0.96 (0.80, 1.14) | 0.61 |

| TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio | 1.1±1.0 | 2.30 (1.07, 4.97) | 0.034 |

| TGF-β1 4w/pre ratio | 1.0±1.0 | 0.96 (0.54, 1.72) | 0.9 |

Footnote: IL-8= Interleukin-8, TGF-β1= Transforming growth factor bata1

Figure 1.

The levels of IL-8 and TGF-β1 for 65 patients with and without RILT2.

RILT=radiation induced lung toxicity

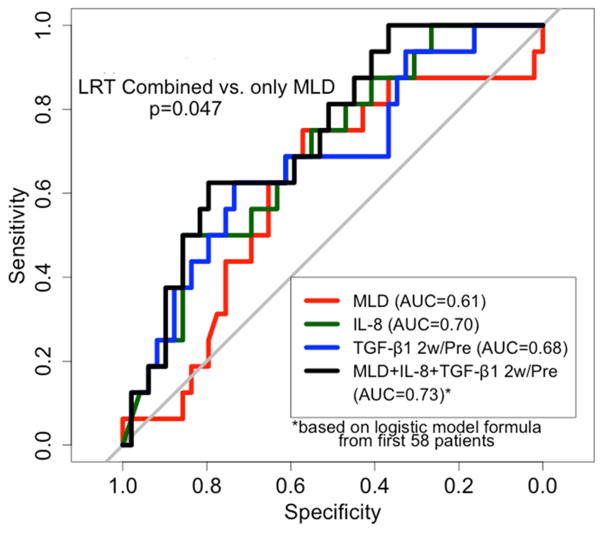

TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio had higher AUC than 2w TGF-β1 level in predicting the risk of RILT, 0.68 and 0.49 respectively, therefore MLD (OR: 1.07, 0.94–1.21, delta), baseline IL-8 level (OR: 0.93, 0.86–0.99, Coefficient: −0.07) and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio (OR: 1.98, 0.89–4.4, Coefficient: 0.68) were included in the final predictive model. The AUC was 0.61 (0.45, 0.77), 0.70 (0.56, 0.84) and 0.68 (0.53, 0.83) with MLD, baseline IL-8 level and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio, respectively. It increased to 0.73 (0.60, 0.87) by combining MLD, pre IL-8 and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio compared to 0.61 by MLD alone (Figure 2). Cutoff points were created for MLD, baseline IL-8 and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio based on maximum values of the sum of sensitivity and specificity: MLD >17.4 Gy, IL-8<8.6 pg/mL, and TGF-β1 ratio>0.86. The incidence of RILT2 were 0% (0 of 3), 5% (1 of 22), 29% (9 of 31), and 67% (6 of 9) for 0, 1, 2, and 3 risk factors, respectively (p=0.003).

Figure 2.

ROC curves based on the sensitivity and specificity of pre IL-8 alone, TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio alone, MLD alone, and all 3 parameters combined to predict RILT2 in validation group (For the curve with all three factors, logistic regression formula from the previous study of 58 patients was applied to the validation set).

RILT=radiation induced lung toxicity

New Model Exploration

In 142 patients, 29 patients (20.4%) developed grade ≥2 RILT (14 radiation pneumonitis, 10 lung fibrosis and 5 both). Among them, 19 (13.4%) grade 2, 9 (6.3%) grade 3 and 1 (0.7%) grade 4.

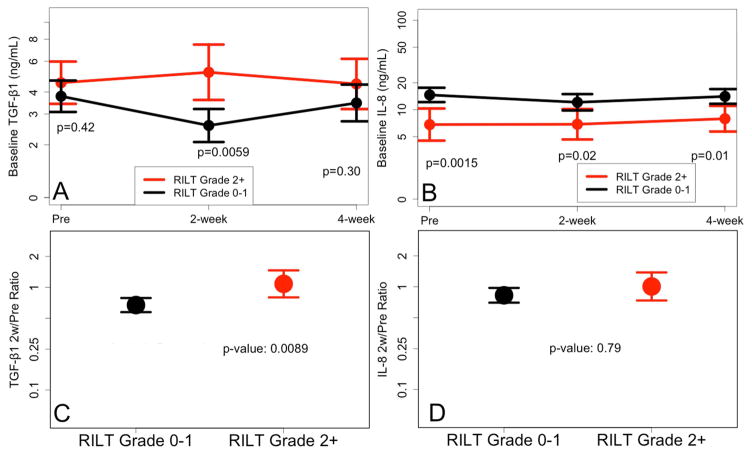

Variables listed in table 1 were evaluated for their association with the risk of RILT, including age, RT dose (BED10) and MLD (for those with MLD available) as continuous variables. None was associated with RILT2 (p>0.05), e.g. the p value of MLD was 0.38 (OR 1.05, 0.94–1.19). The association of levels of 30 cytokines with the risk of RILT was shown in Table e1. Only IL-8 and TGF-β1 were significantly associated with the risk of RILT2. Lower levels of IL-8 at baseline, 2w and 4w during RT were associated with higher risk of RILT2 (Figure 3). Higher TGF-β1 level at 2w during RT or higher TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio were associated with higher risk of RILT2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The levels of IL-8 and TGF-β1 for 142 patients with and without RILT2. RILT=radiation induced lung toxicity

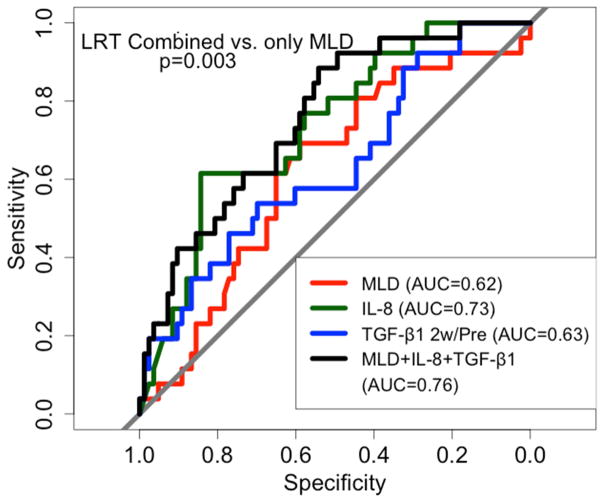

Additional variable weren’t identified so that the combined model was refit with the same variables: MLD (OR: 1.09, 0.99–1.21, Coefficient: 0.09), baseline IL-8 level (OR: 0.91, 0.85–0.97, Coefficient: −0.09) and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio (OR: 1.66, 0.92–2.99, Coefficient: 0.51). The AUC was 0.62 (0.5, 0.74), 0.73 (0.63. 0.84) and 0.63 (0.51, 0.76) with MLD, baseline IL-8 level and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio, respectively. The AUC increased to 0.76 (0.69, 0.88) by combining MLD, pre IL-8 and TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio compared to 0.62 by MLD alone (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ROC curves based on the sensitivity and specificity of pre IL-8 alone, TGF-β1 2w/pre ratio alone, MLD alone, and all 3 parameters combined to predict RILT2 in new model exploration group with all factors available.

RILT=radiation induced lung toxicity

Discussion

We validate that IL-8 and TGF-β1 are important predictors for RILT in patients with NSCLC. Similar to our previous result in 58 patients [4], we demonstrated in an independent dataset with 65 new patients that lower baseline IL-8 level and higher TGF-β1 ratio 2w/pre were significantly associated with increased risk of RILT. Combining IL-8, TGF-β1 and MLD into a single model improved the predictive ability compared to MLD alone. To our knowledge, this is the first study in literature to validate that IL-8 and TGF-β1 are predictors of RILT, though with small sample size. The findings indicate that IL-8 and TGF-β1 are promising cytokines which could be used in predicting the risk of RILT or as targets to prevent RILT. It is also of interest to note that, despite of a larger sample size, we failed to detect other cytokines associated with RILT in the combined dataset.

TGF-β1 is a key cytokine in the fibrotic process that induces phenotypic modulation of human lung fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, and it is a potent stimulator of collagen protein synthesis [6]. The predictive value of TGF-β1 for human lung toxicity was first reported by Anscher et al. (1993) in individuals with advanced breast cancer treated by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation [7]. Further studies from our group demonstrated that changes in plasma TGF-β1 levels may identify individuals at high risk for the development of RILT [8–11]. A persistently elevated TGF-β1 above baseline level at the end of RT [8, 12], or the ratio of during RT TGF-β1 level to baseline level [13] or a significant elevation of TGF-β1 level at 4 weeks after RT [14] were significantly associated with RILT. In a combined analysis of 165 patients from Beijing and Michigan, Zhao et al found the elevation of TGF-β1 at 4 weeks during RT compared to baseline was predictive of RILT in both separate and combined datasets [15]. However, some studies failed to confirm the above findings [16, 17], largely attributed to platelet contamination of plasma samples Nevertheless, a meta-analysis including 7 studies showed end/pre-RT TGF-β1 ratio ≥1 was a risk factor for radiation pneumonitis [2]. In this study, we confirmed that a higher TGF-β1 ratio 2w/pre was significantly associated with increased risk of RILT. This finding is potentially useful, because we could predict RILT at 2 weeks during RT by testing the change of TGF-β1 level, and have the opportunity to adjust and optimize further therapy. Furthermore, the TGF-β1 blockade, though not tested in the RILT setting, might have the potential to push the cytokine interaction into a possibly favorable inflammatory, but not fibrotic profile, thus preventing or treating RILT [18].

IL-8 is interesting, as it has chemotactic activity for leukocytes and induces collagen synthesis and cell proliferation [19] in animal studies but it has been consistently found to have anti-inflammatory effect in humans [20] [21]. In addition to our previous findings with 58 patients [4] and current findings in this study, Hart et al. also reported that low IL-8 was correlated with increased risk of RILT in NSCLC [20]. Meirovitz et al found that low IL-8 was associated with the need for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube installation due to mucositis during RT of head and neck squamous cell cancers [21]. Though there are few reports on the role of IL-8 in predicting radiation induced toxicity, these findings were consistent with our findings in that the lower the baseline IL-8 level, the higher the toxicity. IL-8 may play an important role against irradiation damage and the mechanism needs further investigation.

MLD is a well-recognized predictive factor for RILT [1, 2]. MLD was not significant in our series, which might be owing to that 60/142 (~40%) of these patients were treated by fixed MLD prescription per protocol description. As it is an important dosimetric factor guiding our daily practice, MLD was considered as the control, and was also included in our final model of IL-8 and TGF-β1. Similar to our previous findings, this study demonstrated that the model combing MLD, TGF-β1 ratio and IL-8 can predict RILT more accurately than MLD alone. Future study should validate this finding in multicenter setting and conduct clinical trials to decrease MLD in patients with high risk features of IL-8 and TGF-β1.

Unfortunately, no additional useful markers were identified among the 30 cytokines we measured in 142 patients. Studies with larger size samples are warranted to build stronger models that can possibly incorporate more cytokine information, as the small sample size limits the number of cytokine factors which can be included in a model without over fitting our data. There is likely more useful information about RILT risk that can be obtained from cytokine levels that larger sample sizes can better elucidate, but it is unknown to what extent RILT appears after a certain RT dose threshold and to what extent it is an intrinsic host response, less related to dose.

The strength of this study is that it validated the predictive value of IL-8 and TGF-β1 for RILT in an independent dataset. These results warrant further validation in a larger population from multiple centers. If the findings are further confirmed, these cytokines, available in the early course of RT, could serve as surrogate markers to minimize the consequence of lung injury from radiation.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

The risk factors for radiation-induced lung toxicity (RILT) of 142 patients with stage I-III NSCLC treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) from prospective studies were evaluated. We validated that combination of mean lung dose, baseline IL-8 level and TGF-β1 2 week/pretreatment ratio provided a more accurate model to predict the risk of grade ≥2 RILT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

Disclosure of funding received for this work: this study was supported in parts by R01CA142840 (PI: Kong) and P01CA059827 (PI: Ten Haken and Lawrence)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rodrigues G, Lock M, D’Souza D, et al. Prediction of radiation pneumonitis by dose - volume histogram parameters in lung cancer--a systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang XJ, Sun JG, Sun J, et al. Prediction of radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:2103–2116. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1284-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong FM, Wang S. Nondosimetric risk factors for radiation-induced lung toxicity. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2015;25:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenmark MH, Cai XW, Shedden K, et al. Combining physical and biologic parameters to predict radiation-induced lung toxicity in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with definitive radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong FM, Hayman JA, Griffith KA, et al. Final toxicity results of a radiation-dose escalation study in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): predictors for radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsoutsou PG, Koukourakis MI. Radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis: mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis and implications for future research. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1281–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anscher MS, Peters WP, Reisenbichler H, et al. Transforming growth factor beta as a predictor of liver and lung fibrosis after autologous bone marrow transplantation for advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1592–1598. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306033282203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anscher MS, Kong FM, Andrews K, et al. Plasma transforming growth factor beta1 as a predictor of radiation pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anscher MS, Kong FM, Jirtle RL. The relevance of transforming growth factor beta 1 in pulmonary injury after radiation therapy. Lung Cancer. 1998;19:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(97)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anscher MS, Kong FM, Marks LB, et al. Changes in plasma transforming growth factor beta during radiotherapy and the risk of symptomatic radiation-induced pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anscher MS, Marks LB, Shafman TD, et al. Using plasma transforming growth factor beta-1 during radiotherapy to select patients for dose escalation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3758–3765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.17.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu XL, Huang H, Bentel G, et al. Predicting the risk of symptomatic radiation-induced lung injury using both the physical and biologic parameters V(30) and transforming growth factor beta. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:899–908. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao L, Sheldon K, Chen M, et al. The predictive role of plasma TGF-beta1 during radiation therapy for radiation-induced lung toxicity deserves further study in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JY, Kim YS, Kim YK, et al. The TGF-beta1 dynamics during radiation therapy and its correlation to symptomatic radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:59. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao L, Wang L, Ji W, et al. Elevation of plasma TGF-beta1 during radiation therapy predicts radiation-induced lung toxicity in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a combined analysis from Beijing and Michigan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jaeger K, Seppenwoolde Y, Kampinga HH, et al. Significance of plasma transforming growth factor-beta levels in radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novakova-Jiresova A, Van Gameren MM, Coppes RP, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta plasma dynamics and post-irradiation lung injury in lung cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsoutsou PG. The interplay between radiation and the immune system in the field of post-radical pneumonitis and fibrosis and why it is important to understand it. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:1781–1783. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.938049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward PA, Hunninghake GW. Lung inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:S123–129. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.nhlbi-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart JP, Broadwater G, Rabbani Z, et al. Cytokine profiling for prediction of symptomatic radiation-induced lung injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1448–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meirovitz A, Kuten M, Billan S, et al. Cytokines levels, severity of acute mucositis and the need of PEG tube installation during chemo-radiation for head and neck cancer--a prospective pilot study. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.