Abstract

Background/Aims

We assessed whether cognitive and functional decline in community-dwelling patients with mild Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia were associated with increased societal costs and caregiver burden and time outcomes.

Methods

Cognitive decline was defined as a ≥3-point reduction in the Mini-Mental State Examination and functional decline as a decrease in the ability to perform one or more basic items of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL) or ≥20% of instrumental ADL items. Total societal costs were estimated from resource use and caregiver hours using 2010 costs. Caregiver burden was assessed using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI); caregiver supervision and total hours were collected.

Results

Of 566 patients with mild AD enrolled in the GERAS study, 494 were suitable for the current analysis. Mean monthly total societal costs were greater for patients showing functional (+61%) or cognitive decline (+27%) compared with those without decline. In relation to a typical mean monthly cost of approximately EUR 1,400 at baseline, this translated into increases over 18 months to EUR 2,254 and 1,778 for patients with functional and cognitive decline, respectively. The number of patients requiring supervision doubled among patients showing functional or cognitive decline compared with those not showing decline, while caregiver total time increased by 70 and 33%, respectively and ZBI total score by 5.3 and 3.4 points, respectively.

Conclusion

Cognitive and, more notably, functional decline were associated with increases in costs and caregiver outcomes in patients with mild AD dementia.

Key Words: Cognition, Activities of daily living, Health care costs, Caregivers, Alzheimer disease, Disease progression, Health resources, Outcome assessment (health care)

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD), characterized by cognitive decline with impairment in activities of daily living (ADL), as well as behavioral and psychological symptoms, has multiple impacts on the individual and also on society. Burden experienced by caregivers in terms of time and stress can be considerable [1, 2, 3,4], and patients with AD incur significant health care and community care costs, including direct and indirect medical costs [4]. The overall societal costs and burden on caregivers will continue to increase as the population ages [5, 6].

The amount and type of care required by patients with AD changes as the disease progresses, and several studies have provided data on costs of care for dementia or AD within Europe at varying levels of disease severity [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16], although few have used longitudinal designs.

The GERAS study is a large longitudinal observational study of costs and resource use associated with AD in France, Germany, and the UK [17]. Health outcome data from such large longitudinal studies can provide important real-world information on disease progression and associated resource use and costs, although available definitions of progression in the AD literature all vary considerably in their sensitivity [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26] given considerable heterogeneity in individual rates of progression among patients with AD. A number of studies have characterized cognitive decline in patients with AD using Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [27] scores, but there is little consensus on what magnitude or rate of decline constitutes an appropriate threshold for decline. A clinically meaningful change in MMSE over any interval has been defined as >3 points by Clark et al. [19] with an average annual decline of 3.4 points in their patients with AD. Burback et al. [25] reported that a minimally clinically important difference (MCID) in MMSE score was considered to be 3.72 points (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.50–3.95) based on a survey of specialists in neurology and geriatric medicine on the smallest change in MMSE score that was compatible with a noticeable change in the patient's overall condition. Hensel et al. [28] determined that, with repeated assessments at 1.5-year intervals over a mean of 7.1 years, a “reliable” change in MMSE required a change of at least 2–4 points, whereas Palmer et al. [22] defined clinically relevant worsening as a ≥5-point change over a 2-year period. For the 12-month DOMINO (Donepezil and Memantine in Moderate to Severe Alzheimer's Disease) UK trial (n = 127), an MCID for the standardized MMSE of 1.4 was determined by the investigators, based on an agreed 0.4 standard deviation (SD) of the change in score from baseline. The authors propose that deciding on MCIDs prior to analysis of trial results represents good practice in managing clinical trials and aids subsequent interpretation of results [29].

There are few published definitions of functional progression in AD, and none based on the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL). The total ADCS-ADL score ranges from 0 to 78, with higher scores indicating lower functional impairment. The inventory is composed of assessments of basic ADL such as eating, walking, and bathing (6 items assessed with total scores ranging from 0 to 22), and instrumental ADL such as using a telephone, shopping, and finding personal belongings (16 items assessed with total scores ranging from 0 to 56) [30].

Mohs et al. [26] defined functional progression as a clinically evident decline in the ability to perform one or more basic ADL or ≥20% of instrumental ADL present at baseline using the Alzheimer's Disease Functional Assessment and Change Scale score, while Palmer et al. [22] also defined functional progression as a decline in the ability to perform one or more ba sic ADL.

This post hoc exploratory analysis aimed to investigate, in patients with mild dementia due to AD, whether disease progression (using definitions derived from those available in the literature) is associated with increased societal costs and caregiver outcomes (caregiver time and burden), using data from the longitudinal GERAS study [17]. We aimed to overcome data availability issues commonly experienced in longitudinal studies in AD by focusing on patients with mild AD dementia at entry in the GERAS study, thereby minimizing the numbers “dropping out” or being lost to follow-up due to greater disease severity (e.g., due to severe ill health, institutionalization or death). This also reduced the variability in rates of disease progression associated with the degree of baseline impairment [31, 32].

Methods

GERAS Study Design and Population

GERAS was a prospective 18-month observational study of costs and resource use associated with AD for patients and caregivers in France, Germany, and the UK. The study design and baseline characteristics of participants have been described previously [17]. Briefly, community-dwelling patients presenting within the normal course of care were included in the study if aged ≥55 years with a clinical diagnosis of probable AD according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria [33] and an MMSE score [27] of ≤26 points (maximum possible score 30). Patients had to have an informal caregiver willing to participate and undertake responsibility for the patient for at least 6 months.

Patients were excluded if they had a history or signs of stroke or transient ischemic attack, Parkinson disease, or probable Lewy body disease, as were those participating in an interventional study at baseline. Any treatment for AD could be prescribed at the individual physician's discretion throughout the study. Ethical approval was obtained from institution review boards according to local country requirements, and patients (or their legal representative) and caregivers provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Patients were enrolled in the GERAS study between October 2010 and September 2011 and were characterized as having mild (MMSE 21–26 points), moderate (MMSE 15–20 points), or moderately severe/severe (MMSE <15 points) dementia due to AD.

Data Collection

Patient characteristics, number of comorbidities, disease history and caregiver characteristics were collected at baseline. Patient and caregiver treatments and medical conditions were also collected (data not shown).

Cognitive function was assessed by MMSE measurements at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months, and functional ability was assessed by ADCS-ADL score [30] at baseline and at 18 months.

Caregiver burden was assessed at baseline and each follow-up visit (6, 12, and 18 months) using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), a validated and widely used instrument to measure subjective caregiver burden in AD [34, 35, 36].

Costs and caregiver time were estimated from data obtained from resource use assessed using the Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) instrument [37], which captures health care resource utilization for patients and caregivers (e.g., hospitalizations, living accommodation, community care services), and informal caregiver time spent caring for the patient (collected as the time spent assisting the patient with basic or instrumental ADL, and as supervision time). RUD data were collected at baseline and at subsequent visits at 6, 12, and 18 months.

Costs were estimated by applying country-specific unit costs (2010 values) to the recorded health care and social care resources used during the 18-month follow-up from the RUD. Total societal costs during the 18-month follow-up period were used for analyses. These costs were calculated by adding patient health care costs (including medication, hospitalization, and outpatient visits), patient social care costs (including community care services, structural adaptations to the home, and extra financial support), and caregiver informal care costs (excluding caregiver direct health care costs). Informal care cost was calculated using an opportunity cost approach for time spent assisting with instrumental and basic ADL. Caregiver supervision time was assumed to have a zero value cost and was, thus, excluded from cost estimates. See the Supplementary Material from the original GERAS publication for more details on unit costs and sources [17]. Additional cost data were elicited directly from caregivers, including other patient health care and social care costs, caregiver health care costs, and caregiver informal care costs [17].

Population for Analysis

The present analysis was conducted in the mild AD dementia group in GERAS in order to sustain a population of patients of sufficient size over 18 months in whom disease progression could be reliably established. These patients were required to have at least 12 months of follow-up data or to have been institutionalized prior to the 12-month data collection in order to improve the robustness of the assessment of disease progression and further minimize the effect of missing follow-up data.

Definitions of Cognitive and Functional Decline

For this post hoc analysis, clinically meaningful cognitive decline was defined as a decrease from baseline of ≥3 MMSE points at the last available time point and functional decline was defined as a decline at the last visit (18 months) compared with baseline in the ability to perform one or more basic ADCS-ADL item(s), or a decline at the last visit in the ability to perform ≥20% of the instrumental ADCS-ADL items [24, 26].

For this analysis, institutionalized patients were considered as having declined both cognitively and functionally.

Cost and Caregiver Outcomes

Total societal costs over the 18-month period (with imputation for patients discontinuing before month 18 – see next section) and caregiver outcomes (supervision and overall caregiver time and caregiver burden) at the last observed time point (last observation carried forward approach) were compared in patients who declined versus those who did not decline for both cognitive and functional domains.

The following patient, cost and caregiver outcomes were analyzed:

proportion of patients with mild AD dementia assessed as having had clinically meaningful cognitive decline and functional decline during the 18 months’ follow-up

total societal costs over 18 months for managing patients with mild AD dementia considered to have clinically significant cognitive and functional decline versus patients without decline as described

time spent by caregivers looking after patients with mild AD dementia considered to have clinically significant cognitive and functional decline versus patients without decline as described

ZBI score (caregiver burden) of caregivers looking after patients with mild AD dementia considered to have clinically significant cognitive and functional decline versus those without decline as described

Statistical Analyses

Patient and caregiver characteristics at baseline were summarized using descriptive statistics, based on nonmissing observations, and presented as means with SD or 95% CIs as appropriate.

Imputation methods for missing values were applied as discussed by Belger et al. [38] in GERAS analyses for missing total societal cost data: for institutionalized patients, mean monthly costs from the last visit were used for the period until institutionalization and then country-specific monthly costs for institutionalization were used from the time of institutionalization up to 18 months. For patients who died, the last observation carried forward approach was used such that costs from the last known visit were extrapolated up to the date of death (no costs after death were computed). For patients lost to follow-up, multiple imputation, stratified by MMSE group and country, was performed on missing costs, conforming to established views on preferred methods for the analysis of incomplete cost data when the assumption of dropout at random (missing completely at random) is not justified [39]. The list of factors was selected from those identified by Dodel et al. [40].

Total societal costs and overall caregiver time were analyzed using a generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log link, and the results are primarily presented as percentage of increase in patients with decline versus no decline, with corresponding 95% CIs, with adjustments made for baseline cost as well as for country and patient sex.

Caregiver supervision time had a high number of zero values (i.e., where no supervision of the patient was required as defined by the RUD). Consequently, this parameter was evaluated using a zero-inflated negative binomial model, and the results are presented as both percentage of increase and odds ratio (OR) for supervision time >0 h, with corresponding 95% CIs.

ZBI scores were evaluated using simple linear regression. All models included a term for decline (either cognitive or functional) and were adjusted for sex, country, and baseline scores. To assess any potential additional effect of cognitive decline over functional decline, all models were rerun with simultaneous inclusion of terms for both types of decline.

We chose to focus on a descriptive presentation of contrasts rather than on statistical testing with p values, as this is considered good statistical practice in the context of post hoc exploratory analyses.

All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Cognitive and Functional Decline

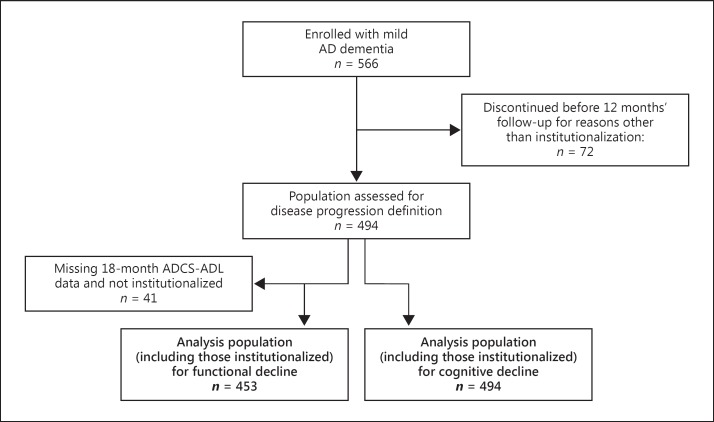

A total of 1,495 patients were enrolled in the GERAS study, of which 566 patients had a diagnosis of mild dementia due to AD. Of these, 494 patients had at least 12 months of follow-up data or had been institutionalized and so were included in the study population for the assessment of disease progression status; all 494 patients were included in the population for the assessment of cognitive decline, of which 255 (51.6%) met criteria for cognitive decline. ADCS-ADL measurements were missing at 18 months in 41 patients, giving a population of 453 patients for the definition of functional decline (Fig. 1), of which 310 (68.4%) met criteria for functional decline.

Fig. 1.

Derivation and disposition of the principal analysis population of patients with mild Alzheimer disease (AD). ADCS-ADL, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory.

The baseline characteristics of those in whom disease progression status was assessed (n = 494 for cognitive progression and n = 453 for functional progression) are described in Table 1. Patients who met criteria for cognitive or functional decline had similar baseline MMSE scores but significantly lower baseline ADCS-ADL scores and numerically higher baseline Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores than patients who did not undergo decline (based on 95% CI), indicating worse functional ability and behavioral symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with mild Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia and their caregivers stratified by whether the patient underwent cognitive or functional decline during the 18-month follow-upa

| Cognitive decline |

Functional declineb |

All | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes | no | yes | no | ||

| Patients | |||||

| Number of patients | 255 | 239 | 310 | 143 | 494 |

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 77.9±6.96 | 76.4±6.75 | 77.9±6.64 | 75.2±7.09 | 77.1±6.89 |

| Sex, % female | 51.0 | 43.5 | 45.2 | 54.5 | 47.4 |

| Years since diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 1.7±1.98 | 1.7±2.04 | 1.8±2.07 | 1.6±2.00 | 1.7±2.01 |

| Comorbidities (mean ± SD), n | 1.5±1.16 | 1.5±1.24 | 1.5±1.17 | 1.4±1.24 | 1.5±1.19 |

| Mean baseline MMSE score (95% CI) | 23.1 (22.9–23.3) | 23.6 (23.4–23.9) | 23.2 (23.0–23.4) | 23.7 (23.4–23.9) | 23.4 (23.2–23.5) |

| Mean baseline total ADCS-ADL score (95% CI) | 55.0 (53.2–56.8) | 61.8 (60.2–63.5) | 55.1 (53.5–56.8) | 64.6 (62.7–66.6) | 58.3 (57.0–59.6) |

| Mean baseline total NPI score (95% CI) | 11.7 (10.3–13.1) | 8.4 (7.3–9.6) | 11.4 (10.1–12.6) | 7.8 (6.4–9.2) | 10.1 (9.2–11.1) |

| Caregivers | |||||

| Caregiver age (mean ± SD), years | 67.5±11.44 | 69.0±11.62 | 68.4±11.35 | 68.0±11.77 | 68.2±11.54 |

| Caregiver sex, % female | 67.8 | 69.7 | 71.0 | 62.2 | 68.8 |

| Caregiver relationship, % | |||||

| Spouse | 67.8 | 75.2 | 69.7 | 74.1 | 71.4 |

| Child | 27.5 | 17.2 | 23.5 | 21.0 | 22.5 |

| Other | 4.7 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 4.9 | 6.1 |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; ADCS-ADL, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Patients with mild AD dementia who had ≥12 months’ follow-up or were institutionalized (patients who were institutionalized were considered to have declined).

41 patients had missing 18-month ADCS-ADL assessments.

Analysis of the overlap between cognitive and functional decline definitions shows them to be in agreement for the majority (58.3%, comprising 38.7% with cognitive and functional decline and 19.6% without cognitive or functional decline) of the patient population (Table 2). Approximately one-quarter of the population achieved the definition of functional but not cognitive decline (24.1%).

Table 2.

Overlap between patients with mild Alzheimer disease dementia who underwent cognitive or functional decline during 18 months’ follow-up

| Functional decline |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| missinga | yesb | nob | totalb | |

| Cognitive decline | ||||

| Yes | 18 (7.1%) | 191 (38.7%) | 46 (9.3%) | 255 (51.6%) |

| No | 23 (9.6%) | 119 (24.1%) | 97 (19.6%) | 239 (48.4%) |

| Total | 41 (8.3%) | 310 (62.8%) | 143 (28.9%) | 494 (100.0%) |

Percentages use the row total as denominator.

Percentages use the total patient population (n = 494) as denominator.

Association between Disease Progression and Costs and Caregiver Outcomes in Patients with Mild AD Dementia

Disease progression, as described in this study by threshold-defined declines in cognition or function, corresponded to increases in costs and caregiver outcomes. Summary statistics for total societal costs, ZBI, and caregiver overall and supervision times are presented in Table 3. Regression-based estimates indicate that, relative to patients without the respective decline, those with functional decline had a larger mean total societal cost (61% higher among patients with functional decline than among those without functional decline, and 27% higher for patients with cognitive decline than for those without cognitive decline), caregiver total time (70 and 33%, respectively), and ZBI total score (5.3 and 3.4 points, respectively) than those with cognitive decline.

Table 3.

Overlap between patients with mild Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia who underwent cognitive or functional decline during 18 months’ follow-up

| Endpoints | Cognition |

Function |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| decline | no decline | decline | no decline | |

| Total societal costa Baseline, EUR/month | ||||

| n | 255 | 239 | 310 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 1,426.3±1,498.8 | 1,112.2±1,360.7 | 1,381.9±1,409.0 | 992.4±1,348.6 |

| Median | 923.9 | 767.8 | 943.9 | 583.2 |

| Q1; Q3 | 509.7; 1,741.3 | 308.7; 1,267.3 | 509.7; 1,636.8 | 245.1; 1,228.7 |

| 18 months, EUR | ||||

| n | 255 | 239 | 310 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 29,761.0±21,315.0 | 21,783.2±16,338.6 | 29,882.1±20,665.8 | 17,006.6±13,481.3 |

| Median | 23,624.1 | 18,205.5 | 24,949.6 | 13,197.3 |

| Q1; Q3 | 14,430.0; 39,405.8 | 11,255.7; 29,107.5 | 15,266.0; 39,246.8 | 82,17.7; 20,310.2 |

| % Increase (95% Clb | 27 (14–42) | 61 (43–81) | ||

| Zarit Burden Interview total score Baseline | ||||

| n | 252 | 237 | 308 | 141 |

| Mean ± SD | 26.9±14.7 | 21.7±13.3 | 26.4±14.3 | 20.2±12.8 |

| Median | 24.0 | 19.0 | 24.0 | 18.0 |

| Q1; Q3 | 16; 36 | 11; 29 | 16; 36 | 10; 26 |

| 18 months | ||||

| n | 237 | 227 | 290 | 140 |

| Mean ± SD | 33.3±16.6 | 26.3±14.3 | 33.3±15.8 | 23.3±13.7 |

| Median | 32.0 | 26.0 | 33.0 | 22.5 |

| Q1; Q3 | 19; 44 | 15; 36 | 21; 44 | 13; 32 |

| Absolute changeb | +3.4 (1.3–5.4) | + 5.3 (3.0–7.5) | ||

| Caregiver overall time, hours/month Baseline | ||||

| n | 255 | 238 | 310 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 142.1±180.5 | 107.4±177.0 | 152.0±194.9 | 79.3±142.1 |

| Median | 75.0 | 35.5 | 90.0 | 30.0 |

| Q1; Q3 | 30; 150 | 4; 120 | 30; 165 | 1; 90 |

| 18 months | ||||

| n | 247 | 238 | 302 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 232.9±236.2 | 166.6±214.9 | 245.3±240.4 | 124.1±182.2 |

| Median | 121.0 | 75.0 | 135.0 | 60.0 |

| Q1; Q3 | 60; 420 | 20; 210 | 60; 420 | 15; 128 |

| % Increase (95% Cl)b | 33 (10–61) | 70 (38–110) | ||

| Caregiver supervision time, hours/month Baseline | ||||

| n | 255 | 238 | 310 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 55.6±125.3 | 46.3±132.5 | 63.3±142.4 | 30.1±102.5 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Q1; Q3 | 0; 30 | 0; 6 | 0; 30 | 0; 13 |

| 18 months | ||||

| n | 247 | 238 | 302 | 143 |

| Mean ± SD | 134.5±212.7 | 85.0±182.8 | 139.8±216.8 | 63.0±158.8 |

| Median | 15.0 | 0 | 15.0 | 0 |

| Q1; Q3 | 0; 240 | 0; 30 | 0; 240 | 0; 15 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI)b | 2.25 (1.49–3.38) | 2.22 (1.40–3.51) | ||

| % Increase (95% CI) | 15% (–17 to 61) | 13% (–24 to 68) | ||

CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; Q1; Q3, quartile 1 and quartile 3 (interquartile range).

Total societal cost was determined by primary analysis using a base-case, opportunity cost approach. Supervision time and caregiver direct medical costs were excluded. Caregiver time was capped at 24 h/day.

Comparisons for patients with decline vs. no decline are modelbased relative increases (i.e., those with no decline serve as the reference group).

Supervision time (e.g., preventing dangerous events such as risks of fire, walking onto a road alone, or outside without appropriate clothing) represents time for values >0.

Cognitive and functional decline had a similar impact on caregiver supervision time; the OR of requiring any supervision time (i.e., >0 h) during the 18-month follow-up among patients with decline versus no decline was 2.25 (95% CI 1.49–3.38) for cognitive decline and 2.22 (95% CI 1.40–3.51) for functional decline.

When both cognitive and functional decline were included in the outcome models, both terms were significant or approached significance for overall caregiver time (p < 0.001 for cognitive decline and p = 0.062 for functional decline), supervision time (p = 0.010 and 0.003, respectively), and total societal cost (p < 0.001 and p = 0.045, respectively). This demonstrates that cognitive and functional decline, although they overlap, have independent or separate effects on these endpoints.

Discussion

The principal finding of this post hoc exploratory analysis of patients with mild AD dementia followed over 18 months in the GERAS study [17] was that clinical progression, using definitions derived from the available literature, appears to be associated with potentially meaningful increases in societal costs and caregiver outcomes. Both cognitive and functional decline were associated with increases in total societal costs, caregiver time, and caregiver burden.

The relative increases in total societal cost would correspond to an increase over 18 months from a typical mean monthly cost of approximately EUR 1,400 (Table 3) to EUR 2,254 in patients with functional decline and EUR 1,778 in those with cognitive decline. These increases represent important cost implications from a societal perspective, given current spending in AD and its increasing prevalence [41].

These results are in agreement with the few previous longitudinal studies that have investigated the association of cognitive and functional decline and/or disease progression with costs in AD or dementia. Two studies, one following patients with mild to moderate AD [42] and the other following patients with AD and/or vascular dementia of varying severities [43], demonstrated a statistically significant association between cognitive and functional decline and increased costs. In patients with dementia of various types, progression to a more severe disease state (assessed using the Clinical Dementia Rating scale) was also associated with increased costs, particularly the transition to the most severe state [44]. A modeling study using longitudinal data from a trial of donepezil in patients with AD showed that decline in functional ability significantly predicted increased costs [45]. Notably, only one of these analyses included informal care costs [44], as the present study did.

Informal care is a major contributor to total societal costs in AD [4, 7, 12, 17, 41], particularly in mild to moderate dementia [12]. Our findings may have particular relevance because patients with mild disease are likely targets for future therapies [46, 47]. Should the increase in costs and caregiver outcomes, including caregiver time and burden, eventually prove to be causally related to disease progression, as suggested by the association observed in our present analysis, society may expect a benefit from interventions that slow disease progression in patients with mild disease.

In our analysis, functional decline appeared to be associated with greater increases than cognitive decline in total societal costs and caregiver time and burden. The ability to perform ADL has been found to be the most important predictor of total societal costs by other investigators [11, 41]. Our findings also support the inclusion of functional decline as an endpoint in future economic studies measuring the impact of new interventions in AD dementia.

Cognitive and functional decline as defined for this analysis overlapped in 58.3% of patients with mild dementia due to AD (comprising 38.7% with cognitive and functional decline and 19.6% without cognitive or functional decline) while close to one-quarter of patients (24.1%) met the threshold for functional decline without meeting the threshold of cognitive decline over the study period. Although higher concordance might initially be expected between the 2 definitions of decline, as cognitive impairment has been shown to precede functional impairment when examined using continuous rather than categorical definitions of decline [48], it is possible that, within the heterogeneity of the disease, cognitive impairment may already have occurred at baseline in these patients and we are capturing the impact of that in the functional outcome. Alternatively, the tool used to determine cognitive progression in the current study (MMSE) and the associated threshold of 3 points is not sensitive enough to detect small changes. Indeed, fewer patients overall met the criteria for cognitive versus functional decline. Additionally, the observation of a number of patients with functional decline but no cognitive decline may in part be explained by a relatively liberal definition of functional decline used; nevertheless, this definition is derived from the best available literature [22, 26]. Further work can be done to understand the impact of more conservative definitions when available (the purpose of this analysis was not to derive definitions of cognitive and functional decline). Considerations for determining meaningful decline should include the time frame over which decline is measured, along with the fact that a single threshold may not be the most appropriate method given the heterogeneity of decline, which comprises more than one clinical domain.

ADCS-ADL data were missing for 150/566 (26.5%) patients with mild dementia due to AD first enrolled in the GERAS study, compared with MMSE data, which was missing for only 46/566 (8.1%) patients in the original population of patients with mild AD at entry. Missing data are common in longitudinal observational studies, where many patients may be lost to follow-up for a number of reasons, including institutionalization and death [49, 50, 51].

Accordingly, to minimize the effect of missing data, we restricted the analysis to those patients with mild dementia due to AD and included institutionalized patients in the definition of decline. Although patients may be institutionalized for reasons other than disease progression, including changes in caregiver status, it was considered a reasonable assumption that in most cases patients with AD being institutionalized will have demonstrated cognitive and functional decline.

In the present study, a model that included both cognitive and functional decline showed statistically significant associations of each event with cost and caregiver time, demonstrating that, although the 2 types of decline overlap to a large extent, they have independent effects on these endpoints. Other studies have demonstrated that combined progression definitions are more sensitive for treatment effect in patients with mild and moderate-to-severe AD dementia [52, 53]. Our results suggest that the predefined thresholds for disease progression used in the present analyses are clinically meaningful, given that they are associated with important cost and caregiver outcomes. However, the feasibility of using such thresholds as endpoints in clinical trials needs further exploration, given limitations on the length of trials and sample sizes needed to power studies adequately using these types of binary response endpoints.

Strengths of the Study

This study included a well-defined patient cohort with longitudinal data prospectively gathered over an 18-month period. A large sample size was obtained, and a standardized measure of resource use, including informal care, was used that allowed pooling of data across different countries.

Further, the effects of both cognitive and functional decline, using definitions derived from the literature, on costs and caregiver outcomes were investigated. Both cognitive and functional decline are important facets of AD progression and are recommended endpoints for clinical trials in AD [27].

Limitations of the Study

The definition of functional decline used in the study was based on the best available from the few existing published definitions [22, 26] although none of the definitions are very precise. There is also little consensus on what may constitute meaningful cognitive decline, but again the definition was based on the best available literature [19, 24, 25, 28].

No formal attempt was made to adjust for potential confounding factors. We did adjust for baseline measures in our analyses (as well as for country and patient sex; see Methods), which indirectly accounts for some potential confounding factors. However, our objective was not to establish a causal relationship between clinical progression and outcomes but to investigate their associations. We did not assess the impact of disease type or severity on study outcomes; however, baseline incidences of overall comorbid conditions were similar in the 4 groups of patients.

As already discussed, ADCS-ADL data were not collected at each visit, only at baseline and 18 months, whereas MMSE scores were obtained at baseline and 6, 12, and 18 months, precluding a direct comparison at the same time points and contributing to missing data. The rationale for inclusion of institutionalized patients in the definition of decline has also been mentioned. As institutionalization is often used as an endpoint in studies of the progression of AD dementia, we considered it reasonable from a clinical standpoint to assume that institutionalization represents decline in our analyses.

There is also possible bias from missing data as a result of patient discontinuation, which is common in longitudinal studies. In this analysis, we greatly limited the effect of dropout to 13% (n = 72) of the whole sample of patients with mild AD dementia in GERAS (n = 566) despite our restriction to patients with at least 12 months’ follow-up (applied to ensure our assessment of progression based on MMSE measurements was robust). As baseline characteristics were similar for all patients with mild AD dementia in GERAS [17], it is unlikely that any withdrawals were due to fundamental differences between patients with and without follow-up data. Altogether, the only excluded patients were those for whom no reasonable status of progression could be established, i.e., those who dropped out before 12 months either because they had died or because they had discontinued for reasons other than institutionalization. Although it is possible that cognitive or functional decline might drive early discontinuation, other unrelated factors (such as the caregiver no longer being available) might also be relevant and this could therefore not be factored into the analysis.

It should also be recognized that there may be potential difficulties in the interpretation of results when combining outcome data from different countries in which practices can vary in the approach to and management of AD. However, the RUD instrument, used to obtain resource use data in the GERAS study, has been validated for use in community-dwelling patients [54] and allows comparison of costs across different countries [55].

Conclusions

In this analysis of patients with mild AD dementia followed over 18 months, clinical progression, using definitions derived from the available literature, was associated with potentially meaningful increases in societal cost and caregiver outcomes. Cognitive and functional decline were both associated with increases in total societal costs, and caregiver time and burden, with functional decline appearing to have the greater impact. The utility of using thresholds for cognitive and functional decline as secondary endpoints in clinical trials should be explored further to confirm them as clinically relevant.

Disclosure Statement

K.K.-W., G.D.A., and C.R. are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. J.L. is a full-time contractor for Eli Lilly. R.W.J., G.B., B.V., J.M.A., R.D., J.M.H., and A.W. have received financial compensation from Eli Lilly for participation on the GERAS Advisory Board.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Brian Cary, Iain Patefield, Claire Lavin, and Karen Goa (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this article, funded by Eli Lilly and Company; in addition, we are grateful to the patients, carers, and investigators who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Argimon JM, Limon E, Vila J, Cabezas C. Health-related quality of life in carers of patients with dementia. Fam Pract. 2004;21:454–457. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. NICE technology appraisal guidance 217. 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta217 (accessed January 23, 2015).

- 3.Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos CG, Schneider LS. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:917–927. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d5745d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jönsson L, Eriksdotter Jönhagen M, Kilander L, Soininen H, Hallikainen M, Waldemar G, Nygaard H, Andreasen N, Winblad B, Wimo A. Determinants of costs of care for patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:449–459. doi: 10.1002/gps.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali G-C, Guerchet M, Wu Y-T, Prince M, Prina M.World Alzheimer report 2015. The global prevalence of dementia, pp 10–27. Alzheimer's Disease International. 2015. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf (accessed February 23, 2016).

- 6.Wimo A, Prince M.World Alzheimer report 2015. The impact of dementia worldwide, pp 56–67. Alzheimer's Disease International. 2015. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf (accessed February 23, 2016).

- 7.Coduras A, Rabasa I, Frank A, Bermejo-Pareja F, López-Pousa S, López-Arrieta JM, Del Llano J, León T, Rejas J. Prospective one-year cost-of-illness study in a cohort of patients with dementia of Alzheimer's disease type in Spain: the ECO study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:601–615. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray AM. Cost of dementia in the pre-enlargement countries of the European Union. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:187–196. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauskopf J, Racketa J, Sherrill E. Alzheimer's disease: the strength of association of costs with different measures of disease severity. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quentin W, Riedel-Heller SG, Luppa M, Rudolph A, König HH. Cost-of-illness studies of dementia: a systematic review focusing on stage dependency of costs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:243–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustavsson A, Brinck P, Bergvall N, Kolasa K, Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. Predictors of costs of care in Alzheimer's disease: a multinational sample of 1,222 patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustavsson A, Cattelin F, Jönsson L. Costs of care in a mild-to-moderate Alzheimer clinical trial sample: key resources and their determinants. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handels RL, Wolfs CA, Aalten P, Verhey FR, Severens JL. Determinants of care costs of patients with dementia or cognitive impairment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:30–36. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318242da1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leicht H, Heinrich S, Heider D, Bachmann C, Bickel H, van den Bussche H, Fuchs A, Luppa M. Net costs of dementia by disease stage. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:384–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesterton J, Wimo A, By A, Langworth S, Winblad B, Jönsson L. Cross sectional observational study on the societal costs of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:358–367. doi: 10.2174/156720510791162430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reese JP, Hessmann P, Seeberg G, Henkel D, Hirzmann P, Rieke J, Baum E, Dannhoff F, Müller MJ, Jessen F, Geldsetzer MB, Dodel R. Cost and care of patients with Alzheimer's disease: clinical predictors in German health care settings. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:723–736. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wimo A, Reed CC, Dodel R, Belger M, Jones RW, Happich M, Argimon JM, Bruno G, Novick D, Vellas B, Haro JM. The GERAS study: a prospective observational study of costs and resource use in community dwellers with Alzheimer's disease in three European countries – study design and baseline findings. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:385–399. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han L, Cole M, Bellavance F, McCusker J, Primeau F. Tracking cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease using the mini-mental state examination: a meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:231–247. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark CM, Sheppard L, Fillenbaum GG, Galasko D, Morris JC, Koss E, Mohs R, Heyman A. Variability in annual Mini-Mental State Examination score in patients with probable Alzheimer disease: a clinical perspective of data from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:857–862. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.7.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortes F, Nourhashémi F, Guérin O, Cantet C, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, Ousset PJ, Vellas B, REAL-FR Group Prognosis of Alzheimer's disease today: a two-year prospective study in 686 patients from the REAL-FR Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vellas B, Hausner L, Frölich L, Cantet C, Gardette V, Reynish E, Gillette S, Agüera-Morales E, Auriacombe S, Boada M, Bullock R, Byrne J, Camus V, Cherubini A, Eriksdotter-Jönhagen M, Frisoni GB, Hasselbalch S, Jones RW, Martinez-Lage P, Rikkert MO, Tsolaki M, Ousset PJ, Pasquier F, Ribera-Casado JM, Rigaud AS, Robert P, Rodriguez G, Salmon E, Salva A, Scheltens P, Schneider A, Sinclair A, Spiru L, Touchon J, Zekry D, Winblad B, Andrieu S. Progression of Alzheimer disease in Europe: data from the European ICTUS study. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:902–912. doi: 10.2174/156720512803251066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer K, Lupo F, Perri R, Salamone G, Fadda L, Caltagirone C, Musicco M, Cravello L. Predicting disease progression in Alzheimer's disease: the role of neuropsychiatric syndromes on functional and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:35–45. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soto ME, Andrieu S, Arbus C, Ceccaldi M, Couratier P, Dantoine T, Dartigues JF, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, Ousset PJ, Poncet M, Portet F, Touchon J, Vellas B. Rapid cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Consensus paper. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:703–713. doi: 10.1007/BF03028618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Saxton J, Sweet RA, Klunk W, DeKosky ST. Alteration of a clinically meaningful outcome in the natural history of Alzheimer's disease by cholinesterase inhibition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burback D, Molnar FJ, St John P, Man-Son-Hing M. Key methodological features of randomized controlled trials of Alzheimer's disease therapy. Minimal clinically important difference, sample size and trial duration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:534–540. doi: 10.1159/000017201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC, Ieni JR, Rogers SL, Perdomo CA, Pratt RD, “312” Study Group A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology. 2001;57:481–488. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hensel A, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Measuring cognitive change in older adults: reliable change indices for the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1298–1303. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.109074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard R, Phillips P, Johnson T, O'Brien J, Sheehan B, Lindesay J, Bentham P, Burns A, Ballard C, Holmes C, McKeith I, Barber R, Dening T, Ritchie C, Jones R, Baldwin A, Passmore P, Findlay D, Hughes A, Macharouthu A, Banerjee S, Jones R, Knapp M, Brown RG, Jacoby R, Adams J, Griffin M, Gray R. Determining the minimum clinically important differences for outcomes in the DOMINO trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:812–817. doi: 10.1002/gps.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas R, Grundman M, Ferris S. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11((suppl 2)):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atchison TB, Massman PJ, Doody RS. Baseline cognitive function predicts rate of decline in basic-care abilities of individuals with dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leoutsakos JM, Forrester SN, Corcoran CD, Norton MC, Rabins PV, Steinberg MI, Tschanz JT, Lyketsos CG. Latent classes of course in Alzheimer's disease and predictors: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:824–832. doi: 10.1002/gps.4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachner YG, O'Rourke N. Reliability generalization of responses by care providers to the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:678–685. doi: 10.1080/13607860701529965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hébert R, Bravo G, Préville M. Reliability, validity, and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging. 2000;19:494–507. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wimo A, Wetterholm A-L, Mastey V, Winblad B. Evaluation of resource utilization and caregiver time in anti-dementia drug trials – a quantitative battery. In: Wimo A, Jönsson B, Karlsson G, Winblad B, editors. Health Economics of Dementia. London: Wiley; 1998. pp. 465–499. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belger B, Haro JM, Reed C, Happich M, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Argimon JM, Bruno G, Dodel R, Jones RW, Vellas B, Wimo A. How to deal with missing longitudinal data in cost of illness analysis in Alzheimer's disease – suggestions from the GERAS observational study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:83. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0188-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oostenbrink JB, Al MJ. The analysis of incomplete cost data due to dropout. Health Econ. 2005;14:763–776. doi: 10.1002/hec.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dodel R, Belger M, Reed C, Wimo A, Jones RW, Happich M, Argimon JM, Bruno G, Vellas B, Haro JM. Determinants of societal costs in Alzheimer's disease: GERAS study baseline results. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Cedazo-Minguez A, Dubois B, Edvardsson D, Feldman H, Fratiglioni L, Frisoni GB, Gauthier S, Georges J, Graff C, Iqbal K, Jessen F, Johansson G, Jönsson L, Kivipelto M, Knapp M, Mangialasche F, Melis R, Nordberg A, Rikkert MO, Qiu C, Sakmar TP, Scheltens P, Schneider LS, Sperling R, Tjernberg LO, Waldemar G, Wimo A, Zetterberg H. Defeating Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:455–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacey LA, Niecko T, Leibman C, Liu E, Grundman M, ELN-AIP-901 Investigator Group Association between illness progression measures and total cost in Alzheimer's disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:745–750. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolstenholme J, Fenn P, Gray A, Keene J, Jacoby R, Hope T. Estimating the relationship between disease progression and cost of care in dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:36–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen CK, Lauridsen J, Andersen K, Kragh-Sørensen P. Cost of dementia: impact of disease progression estimated in longitudinal data. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31:119–125. doi: 10.1080/14034940210134059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustavsson A, Jönsson L, Parmler J, Andreasen N, Wattmo C, Wallin ÅK, Minthon L. Disease progression and costs of care in Alzheimer's disease patients treated with donepezil: a longitudinal naturalistic cohort. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13:561–568. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0334-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeKosky S. Early intervention is key to successful management of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17((suppl 4)):S99–S104. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200307004-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beier MT. Treatment strategies for the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's disease: focus on early pharmacologic intervention. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:399–411. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu-Seifert H, Siemers E, Price K, Han B, Selzler KJ, Henley D, Sundell K, Aisen P, Cummings J, Raskin J, Mohs R, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Cognitive impairment precedes and predicts functional impairment in mild Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:205–214. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coley N, Gardette V, Cantet C, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, Vellas B, Andrieu S. How should we deal with missing data in clinical trials involving Alzheimer's disease patients? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:421–433. doi: 10.2174/156720511795745339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schott JM, Bartlett JW. Investigating missing data in Alzheimer disease studies. Neurology. 2012;78:1370–1371. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318253d66b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lo RY, Jagust WJ, for the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Predicting missing biomarker data in a longitudinal study of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1376–1382. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318253d5b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkinson D, Schindler R, Schwam E, Waldemar G, Jones RW, Gauthier S, Lopez OL, Cummings J, Xu Y, Feldman HH. Effectiveness of donepezil in reducing clinical worsening in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28:244–251. doi: 10.1159/000241877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilkinson D, Andersen HF. Analysis of the effect of memantine in reducing the worsening of clinical symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:138–145. doi: 10.1159/000105162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wimo A, Jönsson L, Zbrozek A. The resource utilization in dementia (RUD) instrument is valid for assessing informal care time in community-living patients with dementia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14:685–690. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wimo A, Gustavsson A, Jönsson L, Winblad B, Hsu M-A, Gannon B. Application of Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) instrument in a global setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]