Abstract

Introduction

We report the feasibility and safety of local anesthesia (LA) in patients having breast-conserving surgery (BCS).

Methods

37 patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 4 having BCS under LA and 54 age-matched subjects with ASA score of 3–4 having BCS under general anesthesia (GA) were included. Patients were retrospectively evaluated for the follow-up duration, duration of surgery, postoperative satisfaction scores (1–10), complication and survival time for locoregional recurrence and overall survival rates.

Results

The mean follow-up duration was 55.09 ± 13.49 months (range 38–104) in GA group, and 58.7 ± 15.5 months (range 20–99) in LA group. There was a significant difference in the duration of surgery (p < 0.001). In the LA group, 5 patients (13.5%) had minor complications including seroma, wound infection or hematoma, whereas 6 patients (11.1%) had minor complications in the GA group (p > 0.05). The re-excision rate due to positive tumor margins was 5.4% (2 patients) in the LA group and 5.5% in the GA group, respectively. The locoregional recurrence-free survival and overall survival rate was not different between 2 groups (p = 0.192, p = 0.93).

Conclusion

BCS under LA seemed to be effective and safe in selected high-risk elderly patients.

Key Words: Breast cancer, Lymph nodes, Surgery, Local anesthesia, Breast-conserving surgery, Safety, General anesthesia

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women aged 55–64 years. Based on the available data, between 2007 and 2011, the number of new cases with breast cancer was reported to be 124.6 per 100,000 women per year [1]. Since age is a known risk factor for breast cancer, the incidence of breast cancer is expected to increase in the near future due to the demographic changes.

Although breast cancers occurring in women aged 75 years or more at the time of diagnosis show a higher proportion of cases with favorable prognostic characteristics, the presence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and heart disease may lead to increased risk at surgery. An association has been reported between older age and peri/postoperative complications, including early postoperative cognitive dysfunction, increased duration of anesthesia, postoperative infection and respiratory complications [2]. Although general anesthesia (GA) provides optimal conditions for breast-conserving surgery (BCS), advanced age and comorbidities may represent a contraindication for operations under GA in older women [3]. Moreover, the operative mortality for patients aged 80 years of older increases more than 2-fold compared to patients of 65–69 years of age [4].

The known intraoperative and postoperative risks of GA for the elderly population encouraged us to perform BCS under local anesthesia (LA) in selected patients. Here we report our experience with BCS performed under LA with light sedation, and compare the outcomes of these patients with age-matched controls having BCS under GA.

Methods

This study comprised patients with early breast carcinoma who received BCS under either LA or GA. Early stage breast carcinoma was defined as T1/T2N0. We performed a hospital-based, case-control study of 37 patients who had an ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score of class III-IV and who received surgery under LA and 54 aged-matched controls who had surgery under GA. The possibility of being operated under LA was offered to all patients with ASA class III-IV. The control subjects were matched to cases in respect to age (older than 65 years) in the same study period. All surgeries were performed at the Institute of Oncology, Istanbul University, between 2007 and 2012. The study was approved by the local Ethics of Human Research Committee, and informed consent form was obtained from each patient prior to the surgery. This manuscript complies with the current laws of the country in which they were performed.

ASA score (I-IV) was used for the operative risk evaluation. Patients with ASA class III-IV (37 patients) underwent surgery under LA, whereas GA was used in patients with ASA class III (45 patients) and also in patients who refused surgery with LA (9 patients).

Anesthesia

An anesthesiologist and a nurse were present at all times during the operation. All patients received continuous monitoring by electrocardiogram and pulse oximetry. Oxygen was given at 2 l/min via oxygen mask without additional respiratory support and oxygen saturation was maintained at 98–100%. For the sedation in the LA group, a combination of 2 mg midazolam (Dormicum, 5 mg/ml, Roche, Switzerland) intravenously (IV), 1 μ/kg fentanyl (5 mg/10 ml, Abbott, USA) IV, and 0.5 mg/kg IV bolus with 0.1 mg/kg/min infusion of propofol (Pofol, 10mg/ml, Sandoz, Switzerland) was used.

Surgical Procedure

A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy was carried out systematically to mark the sentinel node. 60 MBq Technetium-99m nanocolloids, a periareolar radioactive tracer, was injected to the quadrant of the diseased breast.

The surgical procedure began with axillary intervention. The location of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) was identified on the skin using the gamma probe (Clerad, Gamma-Sup, France). 5 ml of 2% prilocaine hydrochloride (Citanest 2%, 20 mg/ml, AstraZeneca, Sweden) was injected intradermally into the axillary site. If needed, more local anesthetic was injected during surgery, but care was taken not to exceed the safe dose. The standard incision started from the anterior and extended to the dorsal axillary hairline. The SLN in the axillary fatty tissue was recognized by its radioactivity. The radioactivity of the excised SLN was recorded ex vivo, and background activity also was evaluated. If background activity was found, further dissection was performed to find any other radioactive lymph node. Frozen sections of the tissue were examined pathologically. Patients with positive SLN then underwent axillary lymph node dissection up to level 2 using extra prilocaine hydrochloride.

The skin incisions for lumpectomy were made on the skin markings. If needed, more local anesthetic was injected. Lumpectomy was completed using the standard procedure. Wounds were closed with a synthetic absorbable surgical suture without drainage. For all patients, intramuscular diclofenac sodium (Voltaren, 75 mg/3 ml, Novartis, Switzerland) was injected to reduce postoperative pain. A standard GA technique was used for the GA group. Postoperative pain control protocols were standardized for both groups and all patients were provided paracetamol 1,000 mg IV. Major and minor complications were assessed during the follow-up. Minor complications included wound infection, hematoma, seroma, lymphedema, breast tenderness, and prolongation of hospital stay. Major complications included brachial plexus injury, pneumothorax, and death due to surgery or anesthesia.

Satisfaction Scores

Each patient was given an anonymous questionnaire about the procedure, which was collected before the patient was discharged postoperatively. The questionnaire comprised 2 pages: the first concerning demographic information, and the other on postoperative findings, such as tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and intensity of pain. The Visual Analogue Scale was used to measure the postoperative breast and axillary pain intensity, tiredness, anxiety, nausea, quality of sleep. Vomiting was evaluated as absent or present. An overall satisfaction score was also calculated. Patients were asked if they would choose similar surgical procedure again and if they would recommend it to family and friends. All of these items were rated on the scale of 1–10 (1 being the lowest score: very bad or lower level of well-being, and 10, the highest: very good or higher level of well-being).

Statistical Analysis

The outcomes, including demographical data, perioperative complications, surgical margins, and histopathological results, were compared between the 2 groups. The normality was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk tests. The Mann-Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables between the 2 groups. Chi-square test or Fisher test was used to compare nominal variables between the groups. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated for time to locoregional recurrence and overall survival time. All analyses were done using SPSS 23 software (IBM, US). p values represent results for 2-sided tests, with values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 37 breast cancer patients in LA group and 54 patients in GA group. The demographic data of the patients are given in table 1. There was no significant difference in age, ASA status and body mass index between the 2 groups. The mean follow-up duration was 55.09 ± 13.49 months (range 38–104) in GA group, and 58.7 ± 15.5 months (range 20–99) in LA group; the difference in follow-up duration was not significant (p = 0.164). The duration of surgery was significantly longer in GA group than LA group (p < 0.001). The surgical procedures performed are given in table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the LA and GA groups

| LA group | GA group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 37 | 54 | |

| Mean age ± SD, year (range) | 72.4 ± 6 (68–76) | 71.1 ± 3.7 (67–81) | 0.67 |

| BMI, mean ± SD (range) | 24.05 ± 3.9 (19–37) | 24.28 ± 3.4 (19–35) | 0.54 |

| ASA status (n) | IV (37) | III (45), IV (9) |

LA = local anesthesia, GA = general anesthesia, SD = standard deviation, BMI = body mass index,

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 2.

Performed surgical procedures

| LA group | GA group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 37 | 54 | |

| BCS + SLNB, n (%) | 24 (64.9%) | 33/54 (61.1%) | 0.65 |

| BCS+AD, n (%) | 13 (35.1%) | 21/54 (38.9%) | 0.53 |

| Duration of surgery, min ± SD (range) | 49 ± 34 (40–60) | 60 ± 45 (35–75) | < 0.001 |

LA = local anesthesia, GA = general anesthesia, BCS = breast-conserving surgery, SLNB = sentinel lymph node biopsy, AD = axillary dissection.

The histopathological characteristics of the tumor in LA and GA groups are given in table 3. The ductal-type breast cancer was the most common type of tumor in both groups. Although tumor size and tumor volume were larger in the LA group than the GA group, this difference was not significant. Positive or close surgical margins (1 mm or < 1 mm) were also similar in the 2 groups. In the LA group, in 2 patients re-excision was performed using the same surgical technique due to positive margins, while 3 patients in the GA group underwent re-excision for positive margins.

Table 3.

Histopathological characteristics of the tumors in the LA and GA groups

| LA group | GA group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor type, n | 0.756 | ||

| Ductal | 31 | 46 | |

| Lobular | 3 | 2 | |

| Mixed type | 2 | 3 | |

| Other | 1 | 3 | |

| Tumor size, mean mm ± SD (range) | 25 ± 11 (0–48) | 22 ± 13.7 (0–55) | 0.229 |

| Tumor volume, mean mm3 ± SD (range) | 249 ± 81 (125–448) | 231 ± 92 (125–512) | 0.163 |

| SLN metastasis, n (%) | 13 (35.1) | 25 (48.1) | 0.261 |

| Micrometastasis, n (%) | 4 (30.7) | 12 (48) | |

| Macrometastasis, n (%) | 9 (69.3) | 13 (52) | |

| Mean number of excised ALN (range) | 14.86 ± 9.5 (6–24) | 13.8 ± 11(18–28) | 0.236 |

| Mean number of excised metastatic ALN (range) | 1.65 ± 1.46 (0–22) | 1.43 ± 2.64 (0–10) | 0.424 |

| Invasive tumor margins, n (%) | 0.191 | ||

| Close to 1 mm | 2 (5.4) | 3 (5.6) | |

| 1–2 mm | 2. (5.4) | 3 (5.6) | |

| ≥ 2–5 mm | 13 (35.2) | 29 (53.7) | |

| > 5 mm | 20 (54.0) | 19 (35.1) |

LA = local anesthesia, GA = general anesthesia, SLN = sentinel lymph node, ALN = axillary lymph node

The identification rate of the SLN biopsy procedure was 100%. The mean volume of anesthetic agent used for lumpectomy and SLN biopsy was 17.43 ± 1.7 ml (range 14–20). When axillary dissection was performed in SLN positive patients, a mean of 22.57 ± 1.45 ml (range 20–25) anesthetic agent was used.

In LA group, 5 patients (13.5%) had minor post-perioperative complications, including seroma formation, wound infection and hematoma. Minor complications occurred in 6 patients (11.1%) in the GA group. There was no significant difference in the rate of minor complications between the 2 groups (p > 0.05). There were no cases of mortality or other major complications related to anesthesia or surgery, and no cases required conversion to GA.

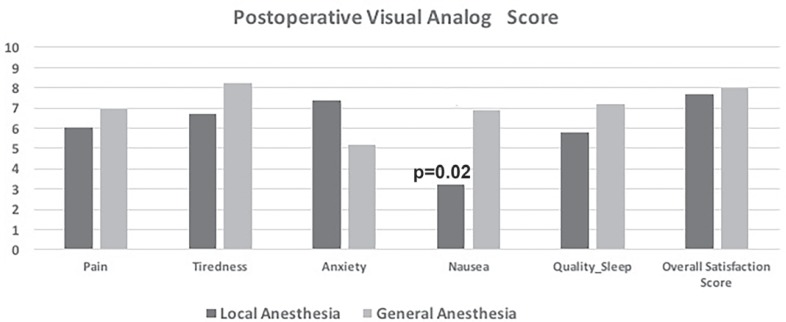

All patients were able to complete the questionnaires using the scales. The mean overall satisfaction score was 7.7 ± 1.6 in LA group and 8 ± 1.7 in the GA group, respectively (p = 0.7). There was no significant difference in postoperative scores for tiredness, anxiety, quality of sleep and pain intensity between the 2 groups (p > 0.05 for all symptoms). Nausea score was significantly higher in the GA group than in the LA group (p = 0.02). The comparison of the postoperative symptom score is shown in figure 1. 36 patients (97%) in the LA group and 54 patients (100%) in the GA group declared that they would have surgery in the same way again. 36 patients (97%) in LA and 52 (96%) patients in GA group said that they would recommend similar surgical intervention to their family and friends.

Fig. 1.

Shows the postoperative symptoms scores in the local anesthesia (LA) and general anesthesia (GA) groups. There is no significant difference between the 2 groups except for nausea (p = 0.02).

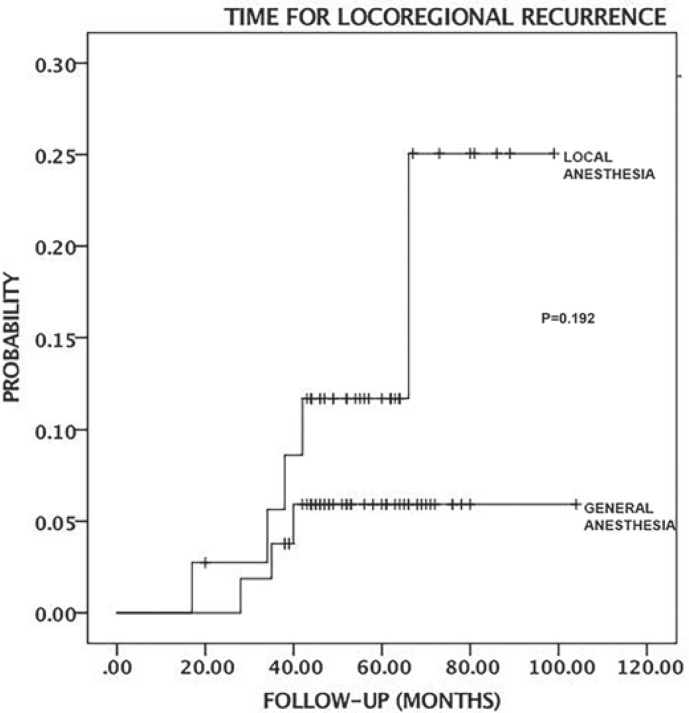

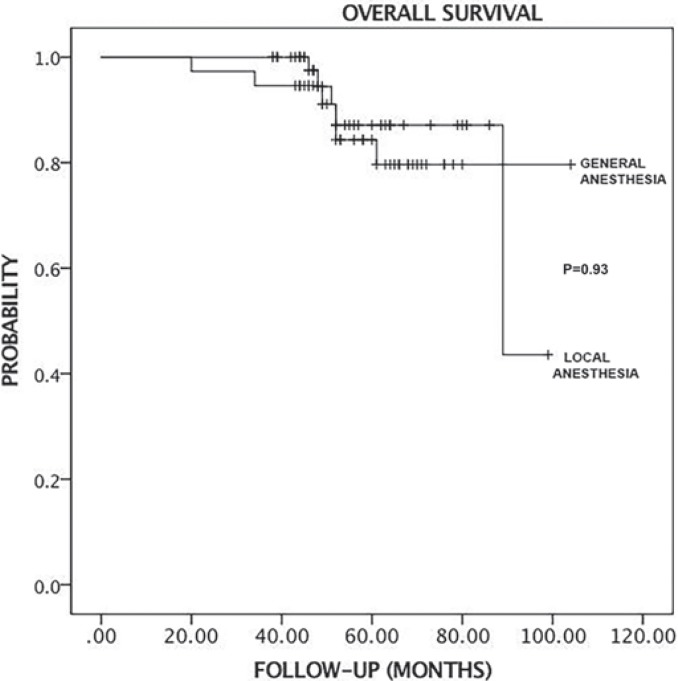

The median follow-up of duration was 56 months (range 20–99) in the LA group and 53 months (range 38–104) in the GA group. All patients were discharged the day after surgery. All patients had physician office visits every 6 months during the follow-up period. In the LA group, 2 patients had the local recurrence, 1 after 17 months and the other after 66 months. In the LA group, 2 patients exhibited distant metastases, 1 to the liver after 34 months and the other to the lung after 42 months. The recurrence rates are given in table 4. There were no significant differences in overall survival probability and time for locoregional recurrence between the LA and GA groups (log Rank, chi-square, p = 0.93; log Rank, chi-square, p = 0.192, respectively). Figures 2 and 3 show the Kaplan-Meier analysis time for locoregional recurrence and overall survival rates.

Table 4.

Recurrence rates in the LA and GA groups

| LA group | GA group | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 37 | 54 |

| Locoregional recurrences, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (3.7) |

| Contralateral recurrences, n (%) | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Distant metastases, n (%) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (3.7) |

LA = local anesthesia, GA = general anesthesia

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve shows the locoregional recurrence time between the local anesthesia (LA) and general anesthesia (GA) group. There is no significant difference (p = 0.192).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve shows the overall survival time in the local anesthesia (LA) and general anesthesia (GA) groups. There is no significant difference (p = 0.93).

Discussion

Breast cancer is a growing health problem in the elderly population. Historically, to control the local growth of this disease, a mastectomy performed under GA has been the technique of choice. Although more than 50% of patients over 70 years of age suffer from 1 comorbidity and 30% suffer from 2 or more comorbidities that might increase the operative risks under GA even for stage I or II breast cancer [5], chronological age should not be considered an exclusion criterion for the surgery.

LA is a safe and effective method of preventing morbidity in patients who have a substantial risk for GA due to older age and comorbidity. Successful major surgeries under LA have already been reported, and LA should be preferred when it is necessary. There have been a limited number of reports showing the outcomes of mastectomy in elderly and high-risk patients [6,7,8]. Based on these studies, mastectomy could be safely performed under LA without increasing the mortality. In our study, 35% of patients had axillary dissection without mastectomy under LA. Although the mean postoperative satisfaction score was found to be slightly higher in patients with axillary dissection than that of SLN patients, the intervention was well tolerated in all patients. No major complications occurred following the surgery under LA.

A Japanese study group [9] reported the oncological safety of BCS and SLN biopsy in 23 patients with a median age of 60 years. The authors used pentazocine for pain reduction in the mapping material injection, lidocaine as (1%) local anesthetic agent and gave IV sedation to the patients during the surgery, which took a median of 77 min. The SLNs were identified in all patients and 1 patient underwent axillary dissection on another day under GA due to positive SLN [10].

Despite having a safe profile, some severe systemic adverse effects may occur after the administration of local anesthetic agents, such as methemoglobinemia and anaphylaxis. A patient's health status, the presence of chronic systemic disease (such as cardiovascular disease, hepatic and renal dysfunction) may amplify the likelihood of these complications. Therefore, a patient should be carefully monitored intra- and postoperatively for any possible sign of local anesthetic reaction to manage these side effects successfully. Moreover, the decision for the appropriate selection of a patient should be done based on the patient's medical, surgical history and pre-anesthesia consultation. In our study, after reviewing the detailed medical history and laboratory evaluation for each patient, all patient had preoperative anesthesia consultation to determine the proper anesthetic agent, and to assess the potential risks that patient might have following the surgery. Eligible patients for LA were selected after this preoperative anesthesia consultation and all patients were carefully assessed for the potential postoperative risks. None of our patients had any anesthesia-related complication. We successfully performed BCS with or without axillary dissection in 37 patients under LA and light sedation IV. We could not detect any side effects related to anesthetic agent.

In our study, there was no significant difference in recurrence and survival rates between the LA group and GA group. In the LA group, 2 of 37 patients (5.4%) had re-excision due to a positive surgical margin, while 3 of 54 patients (5.5%) required re-excision in the GA group. The re-excision rate was not different between the groups. Our results suggested that use of combined LA and mild sedation may be a safe option in selected elderly and high-risk patients.

Our study has some limitations, including the small sample size and observatory design. Prospective studies with a larger number of patients are needed to confirm the superiority of this technique in selected cases.

In conclusion, BCS under LA, as an alternative to GA, seems to be a safe and effective option in high-risk and elderly populations. However, appropriate patient selection should be done with the anesthesiologist, and patients should be carefully monitored for the potential risks postoperatively.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), 2013.

- 2.Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. ISPOCD1 study. Lancet. 1998;351:857–861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285:885–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer JD. Operative mortality with elective surgery in older adults. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betteli G. Preoperative evaluation in geriatric surgery: Comorbidity, functional status and pharmacological history. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennison AR, Watkins RM, Ward ME, Lee EC. Simple mastectomy under local anesthesia. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1985;67:243–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson GW. Total mastectomy under local anesthesia: The tumescent technique. Breast J. 2005;11:100–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph AY, Bloch R, Yee S. Simple anesthesia for simple mastectomies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:189–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1021386722363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirokawa T, Kinoshita T, Nagao T, Hojo T. A clinical trial of curative surgery under local anesthesia for early breast cancer. Breast J. 2012;18:195–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakley N, Dennison AR, Shorthouse AJ. A prospective audit of simple mastectomy under local anesthesia. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22:134–136. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(96)90541-7. erratum appears in Eur J Surg Oncol 1996;22:560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]