Significance

The oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is a sluggish reaction with poor catalytic efficiency, which is one of the major bottlenecks in realizing water splitting, CO2 reduction, and rechargeable metal–air batteries. In particular, the commercial utilization of water electrolyzers requires an exceptional electrocatalyst that has the capacity of delivering ultra-high oxidative current densities above 500 mA/cm2 at an overpotential below 300 mV with long-term durability. Few catalysts can satisfy such strict criteria. Here we report a promising oxygen-evolving catalyst with superior catalytic performance and long-term durability; to the best of our knowledge, it is one of the most active OER catalysts reported thus far that satisfies the criteria for large-scale commercialization of water–alkali electrolyzers.

Keywords: iron, electrocatalytic water splitting, ferrous metaphosphate, oxygen evolution reaction, commercial utilization

Abstract

Commercial hydrogen production by electrocatalytic water splitting will benefit from the realization of more efficient and less expensive catalysts compared with noble metal catalysts, especially for the oxygen evolution reaction, which requires a current density of 500 mA/cm2 at an overpotential below 300 mV with long-term stability. Here we report a robust oxygen-evolving electrocatalyst consisting of ferrous metaphosphate on self-supported conductive nickel foam that is commercially available in large scale. We find that this catalyst, which may be associated with the in situ generated nickel–iron oxide/hydroxide and iron oxyhydroxide catalysts at the surface, yields current densities of 10 mA/cm2 at an overpotential of 177 mV, 500 mA/cm2 at only 265 mV, and 1,705 mA/cm2 at 300 mV, with high durability in alkaline electrolyte of 1 M KOH even after 10,000 cycles, representing activity enhancement by a factor of 49 in boosting water oxidation at 300 mV relative to the state-of-the-art IrO2 catalyst.

Severe deterioration of the environment caused by the consumption of vast amounts of fossil fuels is driving us to explore renewable energy sources (1). Hydrogen (H2) produced from water splitting by an electrochemical process called water electrolysis has been considered to be a clean and sustainable energy resource to replace fossil fuels and meet the rising global energy demand, because water is both the sole starting material and byproduct when clean energy is produced by converting H2 back to water (2, 3). To realize the overall water electrolysis for H2 production, oxygen evolution reaction (OER), also named water oxidation, plays another key role (4). OER is also an important oxidative reaction in obtaining carbon fuels from CO2 reduction (5) and achieving rechargeable metal–air batteries (6), and it has been meticulously studied for more than half a century. However, owing to the sluggish four-proton-coupled electron transfer and rigid oxygen–oxygen bonding, this key process remains a major bottleneck in the water-splitting process. State-of-the-art OER catalysts, such as iridium dioxide (IrO2) and ruthenium dioxide (RuO2), still require overpotentials of around 300 mV to achieve current densities on the order of 10 mA/cm2, not to mention their scarcity and high costs, which severely hinder the substantial market penetration of this technique (7). Thus, it is highly desirable and imperative to develop robust and stable oxygen-evolving electrocatalysts from earth-abundant and cost-effective elements.

Commercial water electrolyzers require a competent electrocatalyst that can efficiently deliver an oxidative current density above 500 mA/cm2 with long-term stability at overpotentials < 300 mV (8, 9). Although various earth-abundant materials have been proven to be efficient catalysts for oxygen evolution, such as transition metal oxides (8, 10, 11), hydroxides (12, 13), oxyhydroxides (14, 15), phosphates (16–18), phosphides (19, 20), metal–organic frameworks (21), and carbon nanomaterials (22), many of them cannot meet the aforementioned commercial criteria for water–alkali electrolyzers, and, most importantly, they may not survive long in high-current operation. To this end, we report a highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction yielding current densities of 10 and 500 mA/cm2 at overpotentials of 177 and 265 mV, respectively, both of which are the lowest overpotential values for the corresponding current densities ever reported, and showing excellent long-term stability.

Results and Discussion

Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction.

We found that the catalyst responsible for the large current density is Fe(PO3)2, which was formed on the surface of the conductive Ni2P/Ni foam scaffold (SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S4). We first investigated the OER activity of this Fe(PO3)2 catalyst and the corresponding reference materials (Ni foam, Ni2P, and IrO2) in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5A. Among these electrodes, the Fe(PO3)2 electrode exhibits the highest OER catalytic activity, where an overpotential as low as 218 mV vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) is required to yield a geometric current density of 10 mA/cm2; whereas, the Ni foam, Ni2P, and the state-of-the-art IrO2 electrodes require 377, 330, and 297 mV vs. RHE, respectively, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5B. This overpotential of 218 mV is much smaller than those of most currently reported OER electrocatalysts (23), which clearly indicates that Fe(PO3)2 is an outstanding OER catalyst in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte (SI Appendix, Table S1). In addition to OER activity, stability is another critical criterion for evaluating the catalysts. We found that Fe(PO3)2 is very stable at 10 mA/cm2 for over 20 h in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5C.

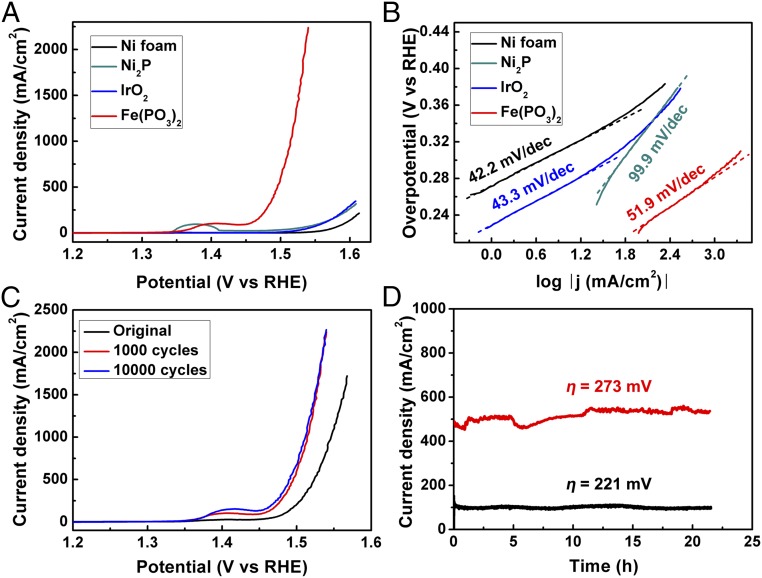

With an eye toward commercial applications, we also measured the catalysts in 1 M KOH electrolyte. The higher OH− concentration leads to higher electrical conductivity and potentially superior catalytic performance. The catalytic performance among the different electrodes shows the same trend (Fig. 1A) as in 0.1 M KOH, but with much higher current densities. Apparently, an overpotential larger than 380 mV is necessary to yield a current density of 500 mA/cm2 for the IrO2 electrode, considerably higher than the 265 mV overpotential needed for the Fe(PO3)2 electrode to reach the same current density. When we apply an overpotential of 300 mV to activate oxygen evolution, this Fe(PO3)2 catalyst yields a current density of 1,705 mA/cm2, which is 341, 30, and 49 times better than that of the Ni foam, Ni2P, and IrO2 catalysts, respectively, suggesting a huge improvement mainly originated from the Fe(PO3)2 itself, rather than from the Ni2P/Ni foam support. The steady-state electrochemical analysis shown in Fig. 1B reveals that this electrode possesses a small Tafel slope of 51.9 mV/dec, from which we can expect that a 177-mV overpotential is needed to reach a current density of 10 mA/cm2 for this electrode. Upon cyclic voltammogram testing, the anodic current density of this electrode exhibits an obvious increase after 1,000 cycles compared with its initial state, and it then maintains nearly the same activity up to 10,000 cycles (Fig. 1C), corroborating the finding that the catalyst is extremely durable to withstand accelerated degradation. Notably, the Fe(PO3)2 electrode sustains at steady catalytic current densities of 100 and 500 mA/cm2 with very low overpotentials of 221 and 273 mV, respectively, even after chronoamperometry testing for 20 h (Fig. 1D). To the best of our knowledge, Fe(PO3)2 is one of the best performing catalysts so far reported and it most successfully fulfills the strict criteria for large-scale commercialization of water–alkali electrolyzers (SI Appendix, Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Electrocatalytic water oxidation activity. (A) Polarization curves recorded on different electrodes with a three-electrode configuration in 1 M KOH electrolyte. (B) The relevant Tafel plots of the catalysts studied in A. (C) Polarization curves of the Fe(PO3)2 catalyst at its initial state and after 1,000 and 10,000 cycles. (D) Chronoamperometric measurements of the OER at high current densities of 100 and 500 mA/cm2 for the Fe(PO3)2 electrode.

Structural Characterization and Possible Mechanisms.

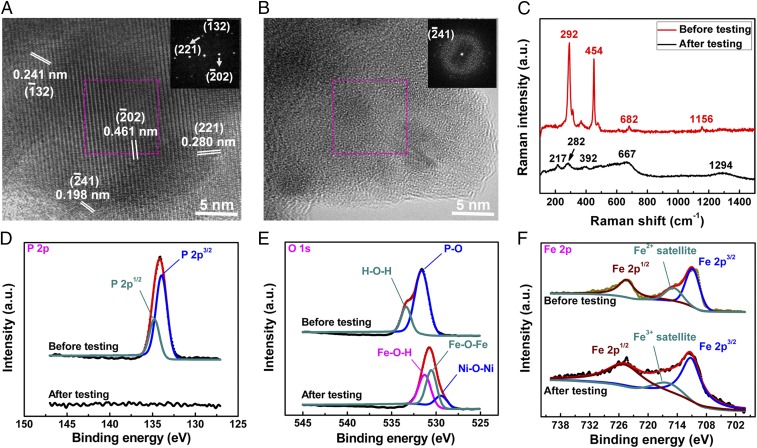

To determine the possible origins of such extraordinary performance, it is essential to elucidate the crystalline structures and surface composition of the electrocatalyst before and after electrochemical OER testing. As mentioned above, Ni foam was used as the conductive support because of its low cost, good conductivity, and 3D macroporous feature (24, 25). Typical SEM images (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) show that the Fe(PO3)2 catalysts are uniformly distributed on the Ni2P/Ni foam surface where a good electrical contact is formed between the (FePO3)2 catalysts and the highly conductive Ni2P, ensuring quick charge transfer between the catalyst and the electrode as indicated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements, discussed below. On the other hand, the crystalline features of these as-grown Fe(PO3)2 particles can be well resolved from the high-resolution TEM image (Fig. 2A), in which many nanocrystals show distinct lattice fringes with 0.461-, 0.280-, 0.241-, and 0.198-nm lattice spacings marked by parallel lines, matching well with the interplanar spacings of the (02), (221), (32), and (41) crystal planes, respectively, of Fe(PO3)2. The fast-Fourier transform (FFT) pattern taken from Fig. 2A consisting of discrete spots is another solid piece of evidence to confirm the crystalline nature of these particles. In contrast, such crystalline material undergoes some structure changes after 10,000-cycle OER testing (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), and evolves into mainly an amorphous material as confirmed by the TEM image and FFT pattern (Fig. 2B), which can be further verified by the Raman spectra due to different vibration modes from different materials (Fig. 2C). It should be noted that no Raman vibration modes are detected on the Ni2P crystals at the excitation laser of 633 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S7); however, two prominent peaks are located at 682 and 1,156 cm−1 for Fe(PO3)2, which can be attributed to the symmetric PO2− stretching vibration modes related to the inequivalent P–Onb bonds and the symmetric stretching vibration modes associated with the P–O–P bonds, respectively. Both are unique to the Fe(PO3)2 crystal. Other Raman peaks below 600 cm−1 are related to network bending modes (26). After OER testing, no such vibration modes of the Fe(PO3)2 crystal are detected, but some other distinctive peaks are observed and are associated with the unique Raman features of amorphous iron oxides (27), rather than those of Ni2P-derived nickel oxides (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), further indicating structure changes in this Fe(PO3)2 crystal during the OER electrocatalysis. In addition, elaborate XPS analysis (Fig. 2 D–F) helps us confirm that the original material is indeed Fe(PO3)2 based on the binding energies of Fe 2p3/2, satellite peak, P 2p, and O 1s core levels extracted from the XPS data (28) and the atomic ratio (SI Appendix, Table S3), and the final compound after OER testing of 10,000 cycles is possibly amorphous FeOOH, judging from the binding energies Fe 2p and O 1s as well as the disappearance of P signals (14, 29). These results suggest that the real catalytic sites may originate from the Fe(PO3)2-derived amorphous FeOOH, which may explain why the catalytic activity improves during the first 1,000 cycles. Whether as-synthesized amorphous FeOOH on Ni foam can perform as well as the Fe(PO3)2-derived amorphous FeOOH is now being studied and will be reported accordingly (Fig. 1E). In fact, when FeOOH catalysts are electrodeposited onto some 3D conductive scaffolds, such as CeO2 or metallic cobalt nanotube arrays on Ni foam, FeOOH has been experimentally proven to be a good OER catalyst with an overpotential of 300 mV for around 100 mA/cm2 current density (14, 30). Structural changes of nonoxide catalysts like selenides and phosphides have been reported during OER operation (11, 19). Finally, it should be noted that there is an additional O 1s XPS peak located at around 529.6 eV. By carrying out Raman measurements on the post-OER Ni2P (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), and XPS analysis on the Ni 2p3/2 binding energies of the original and post-OER Fe(PO3)2 electrode (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), we conclude that a small amount of nickel oxide/hydroxide is evolved from the Ni2P support at the surface during OER electrocatalysis. This observation is consistent with the results reported previously by Hu and coworkers (19), who also reported Ni2P crystals as the starting materials for OER testing. Given that nickel oxide/hydroxide is in situ generated from Ni2P during OER electrocatalysis, it should be noted that a trace amount of iron impurities may incorporate into nickel oxide/hydroxide catalysts as reported previously (31, 32), resulting in the possible formation of Ni–Fe oxide/hydroxide in the post-OER catalysts. The incorporation of a small amount of Fe impurities plays a positive role in boosting the catalytic activity of nickel oxide/hydroxide by improving the electrical conductivity and affecting the electronic structure. Consequently, the final compounds derived from the Fe(PO3)2/Ni2P hybrid after OER testing are probably a mixture of amorphous FeOOH and Ni–Fe oxide/hydroxide, which are responsible for the superior catalytic performance toward water oxidation.

Fig. 2.

Structural characterization. (A and B) High-resolution TEM images and FFT patterns (Insets) of the Fe(PO3)2 catalyst: (A) As prepared, displaying good crystallization, and (B) post-OER (after 10,000 cycles), mainly in an amorphous state. (C) Raman spectra of as-prepared and post-OER (after 10,000 cycles) catalysts. (D) XPS spectra of P 2p binding energies before and after OER tests (after 10,000 cycles). The P 2p peak in the original samples can be deconvoluted into two components, 2p3/2 at 133.9 eV and 2p1/2 at 134.7 eV, confirming the formation of PO3− compounds, and no P signal is detected in post-OER samples, suggesting structure changes on the catalyst surface. (E) XPS spectra of O 1s binding energies before and after OER tests (after 10,000 cycles). The original samples have two components of 531.8 eV for PO3− and 533.4 eV for adsorbed H2O, and post-OER samples show O 1s core-level features consisting of FeOOH and nickel oxide, meaning that amorphous FeOOH is probably the dominant active site for water oxidation. (F) XPS spectra of Fe 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 binding energies before and after OER tests (after 10,000 cycles). It is apparent that the valence state of the Fe element is +2 for the as-synthesized samples, and it is gradually converted to +3 at the surface during water oxidation. The black and red curves in D–F are the original and fitted data, respectively. a.u., arbitrary unit.

High Intrinsic Catalytic Activity.

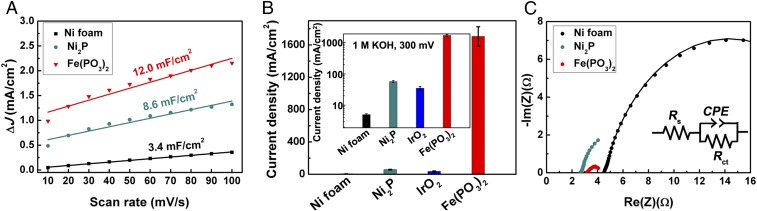

Electrochemically active surface area is an important contributor to boosting the catalytic activity of OER catalysts. To verify this point, a simple cyclic voltammetry method (SI Appendix, Fig. S9) was introduced to determine the double-layer capacitance (Cdl), which has been deemed to be proportional to the effective surface area of the electrode (25, 33, 34). By comparing the capacitance values among different catalysts, we can derive that the Fe(PO3)2 electrode has a capacitance that is a 1.4- and a 3.5-fold increase over those measured for the Ni2P and the Ni foam substrate, respectively (Fig. 3A), indicating some contribution from the highly active surface area of the as-prepared catalysts. However, there is a 30- and 341-fold improvement in the current density of the Fe(PO3)2 electrode compared with those of Ni2P and Ni foam (Fig. 3B), respectively. This suggests that its superior performance cannot be merely attributed to the change of active surface area (Fig. 3A), but to a higher intrinsic catalytic activity for water oxidation reaction than in Ni2P catalysts and Ni foam substrate (11). To gain further insight into the high intrinsic catalytic activity, we evaluated the relevant turnover frequencies (TOFs) of this Fe(PO3)2 catalyst, which can be derived from the equation (35, 36). TOF = j × A/(4 × F × m), where j, A, F, and m are the current density, surface area, Faraday constant, and number of moles of the active catalysts, respectively. This catalyst exhibits a TOF value around 0.12 s−1 per 3d Fe atom at 300 mV in 1 M KOH, assuming that all of the Fe ions in the catalyst are electrochemically active in catalytic water oxidation. This value is very much underestimated, because not every metal atom could be catalytically active in the OER process due to the 3D architecture. Even so, it is larger than many reported OER catalysts like NiFe layered double hydroxides (35, 36). On the other hand, such superior catalytic performance may also be related to the improved electrical conductivity, which has a significant impact on the relevant electron transfer between the catalyst and the support. To clarify this, we performed EIS measurements to check the electrode kinetics of different catalysts (Fig. 3C). It is noteworthy that each Nyquist plot can be fitted by a semicircle with the simplified Randle circuit model shown in the inset, from which we can extract the series resistance (Rs) and charge-transfer resistance (Rct). Indeed, the Fe(PO3)2 electrode possesses a much smaller Rct compared with other catalysts, suggesting facilitated charge transfer between the catalyst and the electrode. Thus, we think that such outstanding catalytic performance may be associated with the high intrinsic catalytic activity, highly electrochemically active surface area, and efficient charge transfer from the electrode.

Fig. 3.

Double-layer capacitance (Cdl) and EIS measurements. (A) Capacitive △J (= Ja − Jc) versus the scan rates for the Fe(PO3)2 electrode compared with Ni2P and Ni foam. (B) Comparison of the current density of the Fe(PO3)2 electrode with those of the benchmark IrO2, Ni2P, and Ni foam at 300 mV. The Inset is the plot of the current density in logarithmic scale. The error bars represent the range of the current density values from three independent measurements. (C) Nyquist plots of different oxygen evolution electrodes at the applied 300 mV overpotential. Inset is simplified Randle circuit model. All measurements were performed in 1 M KOH electrolyte.

Conclusions

A robust and stable Fe(PO3)2 catalyst supported on commercial Ni foam is found to be highly efficient for water oxidation in electrocatalytic water splitting. It only requires an overpotential of 265 mV to yield a current density of 500 mA/cm2 in 1 M KOH with excellent electrochemical durability for 10,000 cycles during OER testing, and can survive at 500 mA/cm2 operation for over 20 h. The fabrication process for such an exceptional electrocatalyst is compatible with industrial standards and is economically viable for large-scale production. We believe our finding is a giant step toward practical and economic production of hydrogen by water splitting, which will significantly contribute to the effort to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate [Fe(NO3)30.9H2O, ≥99.95%; Sigma-Aldrich], Nafion 117 solution (5%; Sigma-Aldrich), sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (NaH2PO2·H2O; Alfa Aesar), iridium oxide powder (IrO2, 99%; Alfa Aesar), potassium hydroxide (KOH, 50% wt/vol; Alfa Aesar), and Ni foam (1.5 mm, areal density 320 g/cm2) were used as received.

Growth of Ferrous Metaphosphate Catalyst on 3D Ni Foam.

Ferrous metaphosphate [Fe(PO3)2] was fabricated by a direct thermal phosphidation process in a tube furnace under Ar atmosphere. First, a 1.6 cm × 0.5 cm piece of commercial Ni foam was dipped into an iron nitrate solution and slowly dried in air, and was then thermally phosphatized in argon gas at 450 °C for 1 h to form Fe(PO3)2 crystals. The phosphorus source was 500 mg sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (NaH2PO2∙H2O), which was put at the upstream at around 400 °C. After thermal phosphidation, the sample was cooled down to room temperature under the protection of argon. The sample was then immersed into the iron nitrate precursor again, followed by a second thermal phosphidation under the same conditions. The as-prepared sample was used as the working electrode directly. The iron nitrate solution was prepared by dissolving 0.75g Fe(NO3)3∙9H2O precursor in 5 mL deionized water with a resistivity of 18.3 MΩ cm. During the thermal phosphidation, the Ni2P was formed on the surface of Ni foam simultaneously with the ferrous metaphosphate. Therefore, the arrangement of our sample is Fe(PO3)2/Ni2P/Ni foam. The catalyst Fe(PO3)2 loading is around 8 mg/cm2.

Synthesis of Ni2P Catalyst on 3D Ni Foam.

For comparison, the Ni2P was synthesized under the same conditions as those for Fe(PO3)2 preparation. The only difference was that the Ni foam was thermally phosphatized directly without iron nitrate solution.

Preparation of IrO2 Electrode on 3D Ni Foam.

To prepare the IrO2 working electrode, 40 mg IrO2, 60 μL Nafion, 540 μL ethanol, and 400 μL deionized water (18.3 MΩ·cm resistivity) were ultrasonicated for 30 min to obtain a homogeneous dispersion. After dip coating IrO2 dispersion onto Ni foam, this sample was placed in the fume hood overnight, followed by heating at 120 °C for 3 h in Ar gas in a tube furnace. The loading of IrO2 catalyst on Ni foam is ∼8 mg/cm2.

Electrochemical Testing.

The electrochemical tests were performed in a three-electrode system in 1 M or 0.1 M KOH electrolyte purged with high-purity oxygen gas continuously. A Pt wire and mercury/mercurous oxide (Hg/HgO) reference were used as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. The catalysts on Ni foam were used as the working electrode directly. The OER catalytic activity was evaluated using linear sweep voltammetry with a sweep rate of 2 mV/s, while the stability of the catalysts was studied by chronoamperometry testing and cyclic voltammetry (CV) with a sweep rate of 50 mV/s. The electrochemical properties were studied normally after the activation by 50 CV cycles. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was measured at an overpotential of 300 mV from 0.1 Hz to 100 KHz with an amplitude of 10 mV. All of the measured potentials vs. the Hg/HgO were converted to an RHE by the Nernst equation (ERHE = EHg/HgO + 0.0591 pH + 0.098). The equilibrium potential (E0) for OER is 1.23 V vs. RHE, so the potential difference between ERHE and 1.23 V is the overpotential.

Raman Measurements.

The Raman spectra were carried out under a Renishaw inVia Raman Spectroscope with He–Ne laser at 633 nm as an excitation source. In general, the acquisition time was 20 s and we did three accumulations. Before measurements, the spectrometer was calibrated using the Raman peak of silicon at 520 cm−1. To avoid oxidation or any structural changes of the samples due to laser irradiation, the laser power was set around 0.2 mW during measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency under Grant FA7000-13-1-0001 and the US Department of Energy under Contract DE-SC0010831, as well as by US Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant FA9550-15-1-0236, the T. L. L. Temple Foundation, the John J. and Rebecca Moores Endowment, and the State of Texas through the Texas Center for Superconductivity at the University of Houston.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1701562114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lewis NS, Nocera DG. Powering the planet: Chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15729–15735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dresselhaus MS, Thomas IL. Alternative energy technologies. Nature. 2001;414:332–337. doi: 10.1038/35104599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray HB. Powering the planet with solar fuel. Nat Chem. 2009;1:7. doi: 10.1038/nchem.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter MG, et al. Solar water splitting cells. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6446–6473. doi: 10.1021/cr1002326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao S, et al. Partially oxidized atomic cobalt layers for carbon dioxide electroreduction to liquid fuel. Nature. 2016;529:68–71. doi: 10.1038/nature16455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang Z, Lu YC. Critical role of redox mediator in suppressing charging instabilities of lithium-oxygen batteries. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:7574–7583. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmo M, Fritz DL, Merge J, Stolten D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2013;38:4901–4934. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RDL, et al. Photochemical route for accessing amorphous metal oxide materials for water oxidation catalysis. Science. 2013;340:60–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1233638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu X, Zhao C. Electrodeposition of hierarchically structured three-dimensional nickel-iron electrodes for efficient oxygen evolution at high current densities. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6616. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie MW, Bell AT. An investigation of thin-film Ni-Fe oxide catalysts for the electrochemical evolution of oxygen. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12329–12337. doi: 10.1021/ja405351s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X, Song F, Hu X. A nickel iron diselenide-derived efficient oxygen-evolution catalyst. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong M, et al. An advanced Ni-Fe layered double hydroxide electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8452–8455. doi: 10.1021/ja4027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long X, et al. A strongly coupled graphene and FeNi double hydroxide hybrid as an excellent electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:7584–7588. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng JX, et al. FeOOH/Co/FeOOH hybrid nanotube arrays as high-performance electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:3694–3698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B, et al. Homogeneously dispersed multimetal oxygen-evolving catalysts. Science. 2016;352:333–337. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Fei H, Ruan G, Tour JM. Porous cobalt-based thin film as a bifunctional catalyst for hydrogen generation and oxygen generation. Adv Mater. 2015;27:3175–3180. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cobo S, et al. A Janus cobalt-based catalytic material for electro-splitting of water. Nat Mater. 2012;11:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nmat3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn HS, Tilley TD. Electrocatalytic water oxidation at neutral pH by a nanostructured Co(PO3)2 anode. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern LA, Feng LG, Song F, Hu XL. Ni2P as a Janus catalyst for water splitting: The oxygen evolution activity of Ni2P nanoparticles. Energy Environ Sci. 2015;8:2347–2351. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang XG, Li W, Xiong DH, Petrovykh DY, Liu LF. Bifunctional nickel phosphide nanocatalysts supported on carbon fiber paper for highly efficient and stable overall water splitting. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:4067–4077. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao SL, et al. Ultrathin metal-organic framework nanosheets for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nat Energy. 2016;1:16184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li JC, et al. A 3D bi-functional porous N-doped carbon microtube sponge electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Energy Environ Sci. 2016;9:3079–3084. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han L, Dong S, Wang E. Transition-metal (Co, Ni, and Fe)-based electrocatalysts for the water oxidation reaction. Adv Mater. 2016;28:9266–9291. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, et al. Three-dimensional flexible and conductive interconnected graphene networks grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat Mater. 2011;10:424–428. doi: 10.1038/nmat3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou H, et al. Efficient hydrogen evolution by ternary molybdenum sulfoselenide particles on self-standing porous nickel diselenide foam. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12765. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang LY, Brow RK. A Raman study of iron-phosphate crystalline compounds and glasses. J Am Ceram Soc. 2011;94:3123–3130. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chemelewski WD, Lee HC, Lin JF, Bard AJ, Mullins CB. Amorphous FeOOH oxygen evolution reaction catalyst for photoelectrochemical water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2843–2850. doi: 10.1021/ja411835a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong YY, et al. Three-dimensional astrocyte-network Ni-P-O compound with superior electrocatalytic activity and stability for methanol oxidation in alkaline environments. J Mater Chem A Mater Energy Sustain. 2015;3:4669–4678. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu JQ, Zheng MB, Shi XQ, Zeng HB, Xia H. Amorphous FeOOH quantum dots assembled mesoporous film anchored on graphene nanosheets with superior electrochemical performance for supercapacitors. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:919–930. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng JX, Ye SH, Xu H, Tong YX, Li GR. Design and synthesis of FeOOH/CeO2 heterolayered nanotube electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv Mater. 2016;28:4698–4703. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JYC, et al. Operando analysis of NiFe and Fe oxyhydroxide electrocatalysts for water oxidation: Detection of Fe4+ by Mössbauer spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:15090–15093. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trotochaud L, Young SL, Ranney JK, Boettcher SW. Nickel-iron oxyhydroxide oxygen-evolution electrocatalysts: The role of intentional and incidental iron incorporation. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6744–6753. doi: 10.1021/ja502379c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabán-Acevedo M, et al. Efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis using ternary pyrite-type cobalt phosphosulphide. Nat Mater. 2015;14:1245–1251. doi: 10.1038/nmat4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou H, et al. Highly efficient hydrogen evolution from edge-oriented WS2(1–x)Se2x particles on three-dimensional porous NiSe2 foam. Nano Lett. 2016;16:7604–7609. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song F, Hu X. Exfoliation of layered double hydroxides for enhanced oxygen evolution catalysis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4477. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma W, et al. A superlattice of alternately stacked Ni-Fe hydroxide nanosheets and graphene for efficient splitting of water. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1977–1984. doi: 10.1021/nn5069836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.