Keywords: Atmospheric variability, Crop yield, NAO, Winter wheat, Grain maize

Highlights

-

•

Links between the large-scale atmospheric circulation and crop yields in Europe are examined.

-

•

An approach has been developed to identify predictors and build empirical climate-crop yield models.

-

•

Large-scale atmospheric circulation explains up to 70% of inter-annual crop yield variability.

-

•

The seasonal crop yield prediction could benefit from integration of derived empirical models into probabilistic framework.

Abstract

Understanding the effects of climate variability and extremes on crop growth and development represents a necessary step to assess the resilience of agricultural systems to changing climate conditions. This study investigates the links between the large-scale atmospheric circulation and crop yields in Europe, providing the basis to develop seasonal crop yield forecasting and thus enabling a more effective and dynamic adaptation to climate variability and change. Four dominant modes of large-scale atmospheric variability have been used: North Atlantic Oscillation, Eastern Atlantic, Scandinavian and Eastern Atlantic-Western Russia patterns. Large-scale atmospheric circulation explains on average 43% of inter-annual winter wheat yield variability, ranging between 20% and 70% across countries. As for grain maize, the average explained variability is 38%, ranging between 20% and 58%. Spatially, the skill of the developed statistical models strongly depends on the large-scale atmospheric variability impact on weather at the regional level, especially during the most sensitive growth stages of flowering and grain filling. Our results also suggest that preceding atmospheric conditions might provide an important source of predictability especially for maize yields in south-eastern Europe. Since the seasonal predictability of large-scale atmospheric patterns is generally higher than the one of surface weather variables (e.g. precipitation) in Europe, seasonal crop yield prediction could benefit from the integration of derived statistical models exploiting the dynamical seasonal forecast of large-scale atmospheric circulation.

1. Introduction

Climate variability and extremes have a profound influence on agricultural systems (Deryng et al., 2014, Siebert and Ewert, 2014, Challinor et al., 2014). Understanding their effects represents a necessary step to assess the resilience of agricultural systems to changing climate conditions as well as to develop adequate adaptation measures (Moore and Lobell, 2014). Numerous studies have investigated the link between climate and crop yields in Europe (e.g. Ceglar et al., 2016, Moore and Lobell, 2015, Hawkins et al., 2013) providing the basis to develop a seasonal crop yield forecasting system and thus enabling a more effective and dynamic adaptation to climate variability and change. Indeed, early and reliable predictions of severe weather events and/or conditions can significantly contribute to the mitigation of adverse effects on crops and alleviate their negative impacts (e.g. Träger-Chatterjee et al., 2014).

Seasonal climate forecasts have been increasingly used across a range of sectors, e.g. energy, water resources, insurance, natural hazards (Marcos et al., 2016, Marcos et al., 2015, Soares and Dessai, 2015, Doblas-Reyes et al., 2013). It has been shown that seasonal forecasts can represent a valuable source of information also for the agricultural management process (e.g. Hansen, 2005, Challinor et al., 2003). However, seasonal crop yield forecasting in Europe poses a great challenge due to the poor seasonal climate forecast skill of some relevant local surface climate variables (e.g. precipitation), showing acceptable skill at mid-latitude regions only for particular seasons (Frías et al., 2010, Shongwe et al., 2007). Predicting extreme events (such as the 2003 heat wave) remains challenging (Weisheimer et al., 2011) in the extra-tropical regions. However, new emerging findings show the potential for a better understanding of the spatio-temporal features of these climatic events, along with associated precursors (Prodhomme et al., 2016, Prodhomme et al., 2015, Pepler et al., 2015, Quesada et al., 2012).

Recent works have demonstrated that key aspects of European and North American winter climate and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) are predictable months ahead (Dunstone et al., 2016, Scaife et al., 2014). Since seasonal forecasts only show modest level of skill in predicting surface climate in Europe, it is therefore important to explore different ways to use selected variables of seasonal forecasts where better skill can be observed, such as in the large-scale atmospheric circulation. Indeed, large-scale climate patterns can produce synchronous variations of local surface variables (e.g. temperature) over large areas and can be generally forecast more accurately (Doblas-Reyes et al., 2003).

The relationship between large-scale teleconnection patterns and crop yields has been widely studied in the past. ENSO-induced variability and its influence on crop yields have been investigated globally (Iizumi et al., 2014) as well as for several different regions of the world: USA (Hansen et al., 1999), southern America (Ferreyra et al., 2001), Australia (Meinke and Hochman, 2000) and Zimbabwe (Phillips et al., 1998). Several local/regional studies in Europe support the existence of a relationship between crop yields and large-scale atmospheric patterns (Irannezhad and Klöve, 2015, Brown, 2013, Sepp and Saue, 2012, Persson et al., 2012, Kettlewell et al., 2003, Gimeno et al., 2002). However, these studies are limited to small spatial domains.

The Euro-Atlantic region is mainly dominated by four large-scale atmospheric modes of variability: North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Eastern Atlantic (EA), Scandinavian (SCAND) and Eastern Atlantic-Western Russia (EAWR) patterns (Casanueva et al., 2014, Casado et al., 2009). Cantelaube et al. (2004) have shown the existence of a relationship between leading winter atmospheric modes of variability and winter wheat yields in Europe. However, the link between teleconnection patterns and climate anomalies over Europe exists also in other seasons (e.g. Casanueva et al., 2014, Krichak et al., 2014, Bladé et al., 2012, Toreti et al., 2010, Yiou and Nogaj, 2004). In addition, combining observed climate information within the growing season (e.g. large-scale atmospheric modes responsible for precipitation, temperature and accumulated soil moisture) with seasonal forecasts for the rest of the crop growth period (e.g. anthesis and harvesting stages) could significantly contribute to an increase of the crop yield predictability.

Thus, the main objective of this study is to further explore and deepen our understanding of the dynamical sources of crop yield predictability in Europe originating from large-scale atmospheric circulation during the growing season for both winter wheat (October–July) and grain maize (March–September). Understanding of dynamic precursors leading to seasonal climate anomalies can significantly contribute to extending the long-range predictability of crop yields. To this aim, a statistical approach is here developed to build climate-crop yield models based on large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns that can be used to set up a seasonal forecast system.

2. Data

Winter wheat and grain maize yields at the national level were obtained from national statistical institutes in Europe (Eurostat, 2016). Fig. S1 shows the national yield time series of both crops aggregated at the national levels. The study period spans from 1980 to 2015; time series having at least 25 years of data were included in this study, as a tradeoff between having long enough time series of crop yields for statistical analysis and largest possible number of countries included in the analysis.

Leading modes of large-scale atmospheric variability in the Euro-Atlantic region were obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. These indices are based on a rotated principal component analysis of monthly standardized geopotential anomalies at 500 hPa (Barnston and Livezey, 1987). Specifically, four leading modes of large-scale atmospheric variability over the Euro-Atlantic region have been used: NAO, EA, EAWR and SCAND.

Daily precipitation and daily mean temperature data were obtained from the MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System (MCYFS) database, established and maintained by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission for the purpose of crop growth monitoring and forecasting (Biavetti et al., 2014). These data are available on a regular 25 km × 25 km grid covering Europe and neighboring countries.

3. Methods

Crop yield time series can be modelled by using two main components: a decadal trend (induced by the combined effects of changes in agro-management practices, environmental and socio-economic factors and climatic changes) and a weather-related component (driving the crop yield variability). A proper estimation of the decadal trend is important, as the influence of slowly changing factors needs to be minimized in order to more accurately capture the effect of the inter-annual climate variability. Three different methods have therefore been compared for this purpose here: polynomial (with linear and quadratic term on both yield and log(yield)) and LOESS (Cleveland, 1979). Then, de-trended yields have been correlated with large-scale circulation indices on monthly to seasonal time scales. As the differences in correlations based on different de-trending methods are only minor (not shown), the polynomial method has been applied on log(yield) to obtain yield anomalies for the subsequent analysis. Yield anomalies Yt are derived as follows:

| (1) |

where Zt denotes the original yield data at year t and with , and being estimated by ordinary least squares. Logarithmic transformation has been selected to reduce problems with heteroscedasticity caused by large differences in yields between countries (Lobell, 2013) and to normalize positively skewed crop yield distribution.

The main statistical model used in this study is:

| (2) |

where Xi,t represents the predictor i in year t and ϵt are the residuals. Xi,t can represent any potential predictor (NAO, SCAND, EA and EAWR) in any of the averaging periods (one, two or three months; see the next sub-section) during the crop growing season. The growing period between October and July is considered for winter wheat, while the period between March and September is considered for grain maize (MCYFS – MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System, 2016). As crop yields and predictor variables are standardized, γ0 is equal to zero. The standardization makes the regression results for the different regions comparable with each other. The model residuals ϵt should be normally distributed, independent and homoscedastic; therefore, these assumptions are tested by using Shapiro, Durbin–Watson and F tests (Wilks, 2006).

3.1. Selection of relevant predictors

The relevant predictors have been selected for each country separately. The potentially relevant modes of atmospheric variability (i.e. the predictors) are constructed for different time aggregation periods, from one to three months. Different aggregation periods are considered due to the varying sensitivity of crop growth to climate anomalies during different growing stages, allowing for short-term (monthly) and long-term (seasonal) influences. All predictors are included into a robust least angle regression scheme (RLARS; Efron et al., 2004) to evaluate and rank the ones contributing the most to the variance of the predicted yield. A bootstrap approach is applied here to improve and stabilize the results obtained by RLARS (Khan et al., 2007). 1000 samples are generated from the original dataset, and for each covariate the average rank is calculated over all samples. The covariates with the smallest average rank from the reduced dataset are chosen as potential predictors for the regression model.

In order to minimize the risk of overfitting, the selection procedure does not allow for overlapping indicators, e.g. winter NAO and NAO for January cannot be selected simultaneously. For each country, all possible combinations of the RLARS-selected predictors are used to build the multiple linear regression model. The final set of predictors is chosen by minimizing the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc; Hurvich and Tsai, 1991).

3.2. Model validation

After the final set of predictors is selected, the inferred regression models are evaluated by leave-one-out (LOO) cross validation, here adopted due to small sample sizes (e.g. Khan et al., 2010). Several measures of prediction quality are calculated: Spearman coefficient of determination (R2), normalized root mean square error (RRMSE) and model efficiency index (NS). RRMSE is calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where and represent the observed and modeled yield anomalies for year t, respectively, and n is the number of years. This relative measure can be used to compare the model performance between different countries. The Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency index (NS, Nash and Sutcliffe, 1970) is defined as:

| (4) |

where denotes the mean of the observed yield. NS normalizes the predicted errors by using the variance of the observed yield. Its values range from −∞ to 1, with 0 indicating the threshold of model efficiency. Values higher than 0 indicate better model performance than the long-term average, while values lower than 0 indicate model predictive skill inferior to the climatology.

3.3. Seasonal predictability of crop yields

The importance of the relevant large-scale atmospheric predictors as the growing season progresses is assessed. For this purpose, the derived statistical models are run by using input data from two parts of the growing season in year t (m being the dividing month):

| (5) |

where the first sum is performed over all the relevant predictors from the beginning of the growing season until month m, whereas the second sum is performed over all the relevant predictors during the remaining part of the growing season after month m. The values of predictors after month m have been set to climatological average values. As an example, if we consider winter wheat and m is set to January, observed values of relevant large-scale predictors from October until January and long-term average values of relevant predictors from February until July are entering the equation. Improvements in crop yield estimation as month m approaches end of growing season are measured by calculating both NS and RRMSE for each month m.

4. Results

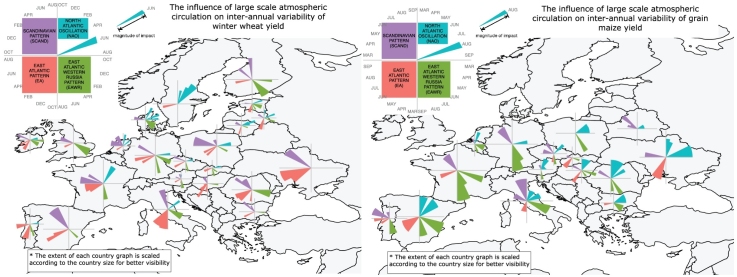

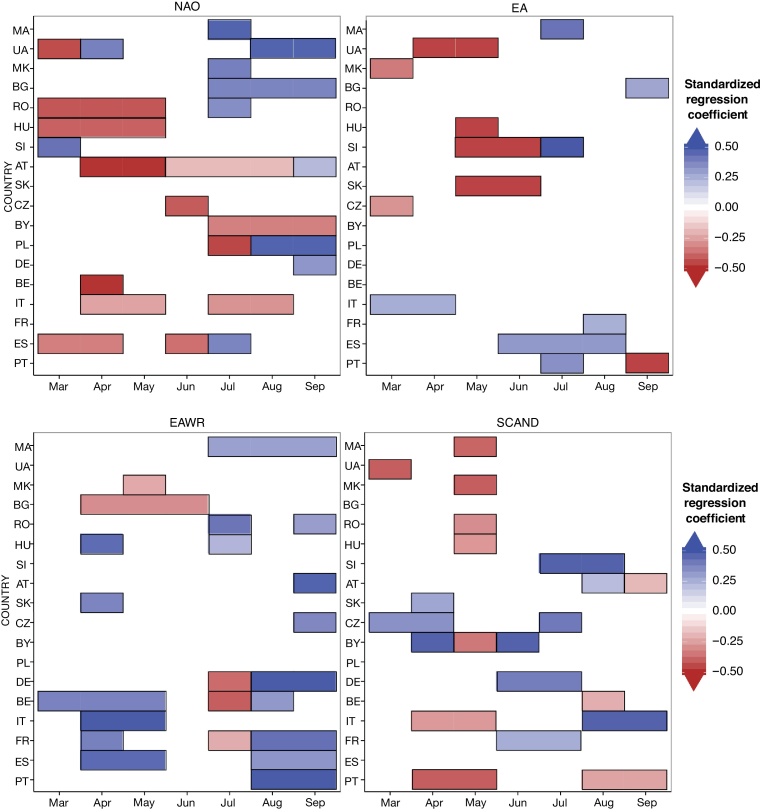

The results of the variable selection procedure using RLARS are presented in Sections 4.1, 4.2 for winter wheat and grain maize, respectively. Standardized regression coefficients of selected large scale atmospheric patterns are shown to compare their influence on the inter-annual crop yield variability in different countries (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 for winter wheat and grain maize, respectively). Standardized regression coefficients express how many standard deviations the crop yield changes for every standard deviation unit change in the large-scale atmospheric predictors. For both crops, the biophysical reasoning of the impact of the selected large-scale atmospheric indicators on crop yield anomalies is discussed. The link between the large-scale atmospheric circulation anomalies and the regional climate is estimated by correlating monthly precipitation and temperature anomalies with the four large-scale atmospheric indicators (Figs. S3–S10). The prevailing climate anomalies during different modes of large scale atmospheric variability are then discussed with respect to (hereafter w.r.t.) their impact on the crop yields during different periods of growing season.

Fig. 1.

Standardized regression coefficients of the four leading atmospheric modes of variability for country-based winter wheat yield regression models. Shown are regression coefficient for the modes of atmospheric variability that are selected as influential predictors. Bounding black box indicates the aggregation period of the index; monthly, two-months and three-months aggregation periods are distinguished.

Fig. 2.

Same as Fig. 1, but for grain maize.

The selected large-scale atmospheric predictors are then used to derive the statistical crop yield prediction models. Their predictive power across Europe is assessed in Section 4.3. Additionally, the relevance of the crop yield decadal trend component is analyzed in Section 4.4.

The derived statistical models are then applied in a simple seasonal crop yield forecasting framework. Seasonal crop yield prediction is usually performed at different times during the growing season period. Since the explanatory variables in the inferred models can span the whole growing season, merging of observations and forecast (here based on the climatology) of the predictors is in some cases needed (Section 4.5).

4.1. Selection of the relevant predictors for winter wheat

4.1.1. Early growing season

The NAO seems to have only a very limited influence in October and November (Fig. 1). Stronger and more spatially coherent signal emerges for the other three modes of atmospheric variability. The EA influence is visible in Romania, Hungary, Austria, a group of countries surrounding the Baltic Sea, Italy and Portugal (where the influence is mainly negative). Positive EA anomalies are related to significant positive temperature anomaly during late autumn over these countries, while the related precipitation anomalies are spatially more varying and are significant in south-eastern Europe, Italy and Portugal (Figs. S5 and S6). In south-eastern Europe and Italy, positive EA anomalies lead to below-average precipitation (above-average in Portugal). Drier conditions during the sowing period might interfere with the field preparation and negatively affect the establishment of wheat crops in autumn and early winter in Romania, Hungary and Italy. The opposite effect with over-wet conditions might cause problems in the field preparation in Portugal. While in the Baltic countries, it is the strong positive temperature anomaly that might cause a faster plant development and make the build up of the resistance to negative temperature (hardening) much slower.

Positive EAWR anomalies in autumn have negative influence on wheat yields in Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, whereas the opposite effect is visible in the Baltic countries. Generally, the positive phase of EAWR is related to negative temperature anomalies in large part of eastern and south-eastern Europe in late autumn and early winter; below-average precipitation in November and December can be observed in central, south-eastern and eastern Europe (Figs. S7 and S8). Negative precipitation and temperature anomalies can delay the crop development in the early season, consequently leading to poor crop establishment before winter. In the Baltic group of countries, winter wheat is usually fully established by the end of the year due to earlier sowing. Negative temperature anomalies help to better build up the resistance to frost kill (i.e. they accelerate hardening).

SCAND fingerprint in autumn can be found in several western European countries as well as in Poland and Greece. Positive SCAND anomalies are related to above-normal temperatures, especially in October (Fig. S10). While precipitation is negatively correlated with SCAND in the Benelux countries, Poland and Greece, positive anomalies prevail in Ireland, the UK and France (Fig. S9). As discussed by Ceglar et al. (2016), positive rainfall anomalies often lead to over-wet conditions in France, limiting the autumn crop establishment.

4.1.2. Overwintering

The positive phase of the NAO is related to positive yield anomalies in Sweden, Denmark and France, where mild winters reduce frost kill risks, enabling better survival. The EA influence is very limited during winter, with several exceptions (Fig. 1). Stronger influence is, however, shown by the EAWR pattern during winter, especially in countries surrounding the Baltic Sea, Denmark, the Netherlands, the UK, Ireland and Italy. With the exception of Italy and the Baltic countries, the positive phase of EAWR is related to negative yield anomalies. As for the SCAND pattern, a positive influence in January and February can be detected in France, Belgium and Germany where the positive phase of SCAND is associated with negative precipitation anomaly. On the other hand, negative SCAND influence is observed in Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovenia and Ukraine in February. A strong negative correlation between the SCAND pattern and temperatures in February over these countries is linked to the outbreak of cold spells, which might lead to frost kill.

4.1.3. Spring and early summer

There is a clear influence of the EA pattern in central and eastern Europe as well as in France and Spain during this period. With the exception of Ukraine, Romania and Poland (where a positive impact is detected during spring), an increase of EA generally decreases yields. In May, which usually coincides with the flowering period, negative EA anomalies are related to above-average temperatures in central and south-eastern Europe and negative precipitation anomalies in western and northern Black Sea regions. Positive EA conditions might therefore negatively influence yields through higher-than-usual temperatures and below-average rainfall in Romania and Bulgaria. France and Spain are characterized by positive influence of EA in early summer with below-average rainfall in June and July that could trigger favorable conditions for ripening and harvesting.

The EAWR has limited influence on crop growth during spring and summer. Negative influence can be observed in Denmark, Finland, Slovakia and Slovenia during the summer months. In central Europe, positive EAWR anomalies in July mainly contribute to increasing crop yield, since they are related to below-average precipitation (favorable for ripening and harvesting).

As for the SCAND pattern, there is clearly a group of countries in south-eastern Europe where significant influence can be observed during spring and early summer. In these regions, positive SCAND anomalies generally lead to lower yields. Positive SCAND anomalies during spring are related to above-average temperatures, especially in May, which generally coincides with the flowering period in south-eastern Europe. For the rest of Europe, the SCAND influence on yields in spring and summer is identified in Poland, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. Positive SCAND anomalies lead to higher yields in Belgium, France and Spain. This could be explained by the favorable weather conditions induced by the positive SCAND phase, with above-average rainfall and slightly lower-than-normal temperatures.

4.2. Selection of the relevant predictors for grain maize

4.2.1. Early growing season

Sowing period is highly relevant for grain maize; it has been shown that the selection of sowing dates might lead to substantially different yields at the end of the growing season (e.g. Tsimba et al., 2013). Soil temperature and soil moisture at emergence are the two most important factors for successful crop establishment. The importance of spring weather conditions (coinciding with the sowing and early vegetative growing stages) is shown by NAO, EAWR and SCAND (Fig. 2).

Negative relationship between maize yields and NAO in spring is detected in Austria, Romania, Hungary, Belgium, Italy and Spain. The magnitude of the impact is higher for Austria, Romania and Hungary, where positive NAO in spring is related to below-average precipitation and above-average temperatures (Figs. S3 and S4). While these conditions might affect the sowing due to low soil moisture, the soil moisture deficit might persist during the vegetative period affecting especially the leaf area growth. Moreover, dry spring often precedes hot summer over south-eastern Europe (Mueller and Seneviratne, 2012), which is also reflected in maize crop yields. Negative rainfall anomalies are associated with positive NAO phase also in Spain and Italy; however, the magnitude of the influence is weaker than elsewhere, probably due to the irrigation. Regarding the EAWR pattern, there are two regions where significant influence is present during spring and early summer: western Europe and south-eastern Europe. In western Europe, positive EAWR is related to strong positive temperature anomalies. In south-eastern Europe, the influence of EAWR is present also in June, when the sensitive flowering period can already occur. Negative relationship between EAWR and yields indicates that below-average rainfall plays an important role during this period. The influence of the SCAND pattern is scattered in several central and south-eastern European countries, with mainly positive influence in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Belarus and Greece, whereas negative influence can be observed in Italy, Hungary and Romania.

4.2.2. Period around anthesis

Grain maize is most sensitive to stress factors during the anthesis period. The majority of maize varieties enter the flowering period by the end of June in southern Europe, whereas central-European varieties enter the flowering period in July (MCYFS – MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System, 2016). The influence of NAO is identified during June and July in several central-European countries (with mainly negative effect) and south-eastern Europe (with positive effect). In the latter, the positive NAO is related to negative temperature anomaly and weak positive rainfall anomaly, which have beneficial effect on maize crop. In addition, according to Casanueva et al. (2014), the NAO is negatively correlated with the number of consecutive dry days and positively correlated with the number of consecutive wet days. The effect is the opposite for central-European countries, where a significant relationship is identified between yield anomalies and NAO during June and July. As for the other large-scale indicators, their influence is rather scattered across Europe without any prevailing spatial pattern.

4.2.3. Grain filling and harvesting

The last part of the grain maize growing season encompasses the grain filling, ripening and harvesting period. Grain filling period usually starts at the beginning of July in southern Europe and at the beginning of August in central European countries (MCYFS, 2016). A stronger influence of NAO and EAWR patterns is observed during this period. The influence of EAWR is mainly positive across Europe. The positive phase of EAWR in August and September is mainly related to below-average rainfall in south-eastern Europe and above-average temperature in major part of central, south-eastern and western Europe. These conditions are beneficial for ripening and harvesting. The positive phase of NAO in August and September is related to below-average precipitation in most of eastern, central and western Europe, with strong positive temperature anomaly in August (Figs. S3 and S4). A negative influence of the NAO at the end of growing season is only detected in Italy and Belarus, whereas positive impact can be observed in Germany, Poland, Austria, Romania and Ukraine.

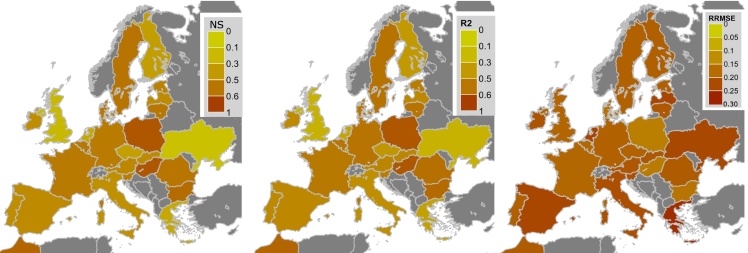

4.3. Predictive power assessment of empirical climate-crop yield models

Selected predictors are used to derive the crop yield anomaly prediction models (Eq. (2)). Two quality measures (R2 and RRMSE) and a consistency measure (NS) are calculated from the LOO cross-validated model estimates. Concerning winter wheat yield anomalies, all derived models are statistically significant with better model performance in central, south-eastern and northern Europe (Fig. 3). The R2 and NS show the highest values in Poland and Hungary. On the contrary, the lowest influence of the large-scale atmospheric variability is observed in Ukraine, the Netherlands, the UK and Greece. According to RRMSE, slightly worse performance is reached in Greece, Spain, Ukraine and the Netherlands. As for the modelling efficiency (NS), values are higher than 0 in all analyzed countries (except for Ukraine). This indicates that regression models based on large-scale atmospheric variability generally lead to better crop yield estimates than the long-term average values.

Fig. 3.

Validation measures for winter wheat regression models based on de-trended crop yield data. Shown are Nash–Sutcliffe model efficiency index (NS), Spearman determination coefficient (R2) and relative root mean square error (RRMSE). All validations measures are calculated based on LOO independent predictions.

Concerning grain maize, derived models are statistically significant in all analyzed countries but Greece (Fig. 4). Better model performance can be observed in central and eastern European countries (with the exception of Slovakia), Macedonia and Portugal. Large-scale climate variability explains around 50% of the inter-annual maize yield variability in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Ukraine, Macedonia and Portugal. Even though the explained variability is lower elsewhere, the model efficiency index NS suggests that the large-scale atmospheric circulation has a clear impact on crop yields. The lowest influence is detected in south-eastern Europe and Slovakia. RRMSE values are slightly higher in south-eastern and eastern Europe (perhaps due to the higher inter-annual variability of maize yields). Generally lower skill (with respect to winter wheat) is expected due to irrigation that alleviates the negative impacts of both drought and heat stress. Indeed, explained variability is lower in countries with higher share of irrigated cropland, such as Spain, Italy and France (Eurostat, 2016). It should be noted though, that lower explained variability is observed also in some countries with low share of irrigated cropland, such as Bulgaria, Romania and Slovakia.

Fig. 4.

Same as Fig. 3, but for grain maize. Black dot over Greece indicates that derived empirical model is not significant.

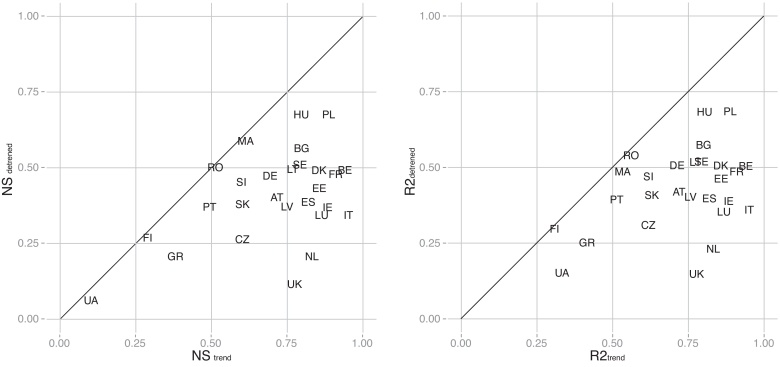

4.4. Importance of decadal trend in crop yield time series

When the decadal trend component is considered into the statistical model, the skill can change substantially. Fig. 5, Fig. 6 show model efficiency (NS) and explained variability (R2) of regression models based on de-trended yield data (Eq. (2)) and the regression models including the decadal trend component (Eq. (1)). The distance of NS and R2 from 1:1 line in these graphs represents the importance of the decadal trend component with respect to the de-trended yield variability; points closer to the 1:1 line indicate that introducing the trend component does not improve substantially the models based only on the large-scale atmospheric predictors. On the contrary, points further away from this line emphasize the role of decadal trend component. In the case of winter wheat, the trend is highly relevant across most of Europe. Large-scale atmospheric variability plays only minor role in several countries (such as the UK and the Netherlands); however, when the trend term is included, the skill of prediction models increases substantially. As for grain maize, no significant influence of decadal trend component is identified in Romania, Hungary, Belarus and Morocco. There is a distinctive group of countries in western Europe (France, Spain, Belgium), central Europe, Italy and Greece, where the trend component contributes substantially to model efficiency and explained variability. This is a consequence of yield progress, which has been more pronounced in western and central European countries over the last 30 years.

Fig. 5.

Scatterplots of NStrend vs NSnotrend (left), R2trend vs R2notrend (right) for country-based winter wheat regression models. The validation metrics on x axis are calculated for regression models including the decadal trend component, while validation metrics on the y-axis are calculated for regression models based on de-trended crop yield data (therefore capturing only the influence of large-scale atmospheric variability). All validations measures are calculated based on LOO independent predictions.

Fig. 6.

Same as Fig. 5, but for grain maize.

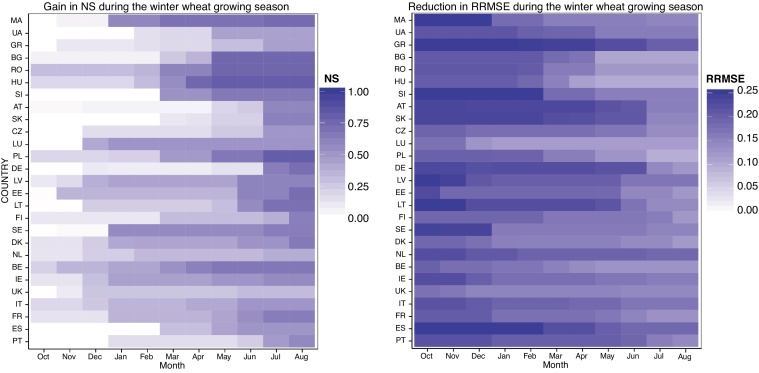

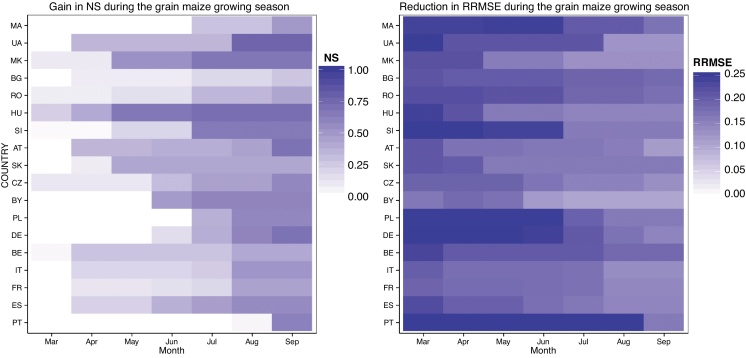

4.5. Seasonal predictability of crop yields

Seasonal prediction of crop yields is assessed in a theoretical framework by merging observed and forecasted values of large scale atmospheric indicators to run the inferred crop yield statistical models at every month during the crop growing season. NS and RRMSE are therefore calculated for each month of the growing season, reflecting the skill of the prediction from sowing until harvesting period. As more observational data is added while approaching the maturity, the NS value increases, while RRMSE decreases. The magnitude of change of both statistical measures also reveals the importance of large scale indicators through the growing season.

The seasonal gain in NS and the reduction in RRMSE clearly show the importance of spring and summer months for both crops (Fig. 7). However, the influence of the autumn and early winter conditions for winter wheat is evident for many countries across western, northern and south-eastern Europe. On the contrary, autumn and winter conditions only represent a weak source of predictability in several countries of central Europe, with the exception of Poland and the Czech Republic. When it comes to the impact of spring and summer conditions on predictability, important differences can be observed between countries. In south-eastern Europe, the highest prediction skill can be observed when the May predictors are included, which is the period coinciding with winter wheat flowering. For the majority of countries in central and northern Europe, also late summer conditions (July and/or August) are important, when the winter wheat grain filling period is affected. This difference is expected as maturity of winter wheat in northern-European countries is usually reached by the end of August (e.g. Olesen et al., 2012).

Fig. 7.

Validation measures NS and RRMSE calculated based on winter wheat yield predictions for different lead times in the season. Validation measures are calculated for each month based on crop yield model predictions using a combination of observed predictors (from the beginning of the growing season until selected month) and long term climatological average of predictors (from the selected month until the end of the growing season) (Eq. (5)). Therefore, more observed data is included in the yield prediction as the end of growing season approaches.

The highest gain in grain maize model efficiency generally occurs between spring and early summer (Fig. 8). Over many countries, conditions in July and August contribute the most to the prediction skill, coinciding with the sensitive stages of flowering and grain filling. However, late spring conditions are important as well over most of Europe, with the exception of Portugal, Germany, Poland and Belarus. The importance of spring conditions is twofold: (a) spring weather conditions affect sowing and early growing stages, and (b) summer soil moisture conditions are dependent on preceding spring rainfall conditions. For instance, summer heat wave conditions have been shown to be linked to dry springs (Mueller and Seneviratne, 2012), which is also reflected in maize yields.

Fig. 8.

Same as Fig. 7, but for grain maize.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The influence of large-scale atmospheric circulation on crop yield anomalies has been assessed during different phases of the crop growing season. Overall, the impact is identified especially during the sensitive phases of crop growth, capturing the response to prevailing regional weather anomalies during different phases and modes of large-scale atmospheric variability. It is worthwhile to emphasize that the tendency for extreme weather events at the sensitive crop growth stages is higher during certain large-scale atmospheric circulation regimes. Casanueva et al. (2014) have shown that SCAND, EA and EAWR play more relevant role than other indices in spring and autumn, when it comes to precipitation extremes (consecutive wet and dry days). This is confirmed as well in our study, especially in south-eastern Europe, where SCAND and EA in late spring affect yield anomalies. A lagged relationship between the NAO and the drought severity has been identified as significant several months in advance in southern Europe (Vicente-Serrano et al., 2016). Likewise, our results suggest that preceding atmospheric conditions might provide an important source of predictability for maize yields in south-eastern Europe.

Differences in the explained variability and model efficiency between regression models including the decadal trend component and models based on de-trended data might be attributed to several factors. A trend can be a consequence of genetic improvements (e.g. change of varieties), technological improvements (e.g. field management, changing sowing dates), intensive fertilizer use and, in the case of grain maize, also increasing use of irrigation. In addition, changing environmental policies may have important influence as well (e.g. Finger, 2010, Brisson et al., 2010). Differences between decadal trends appear mostly between western and eastern European countries, with the trend being generally more pronounced in the former ones. Besides mean yield growth, the technological improvements can also reduce the inter-annual variability of crop yields (e.g. Ceglar et al., 2016), which further masks the climate signal in the crop yield time series. In addition, climate change and climate variability can play a substantial role (Moore and Lobell, 2015). Strong positive trends in western and central European countries have been counteracted by more severe heat waves and droughts during the sensitive stages of crop growth in the last 2 decades (Brisson et al., 2010, Hawkins et al., 2013).

Overall, similar large-scale winter atmospheric patterns have been identified being relevant for winter wheat yield as in Cantelaube et al. (2004). Nevertheless, when it comes to prediction accuracy of the developed statistical models, results differ quite substantially in several countries. Model prediction accuracy in this study is generally higher, especially due to the inclusion of atmospheric predictors during spring and early summer. Even though similar features of winter atmospheric circulation have been identified as relevant for winter wheat growth, our model shows rather lower predictive skill over the UK. This difference can most probably be attributed to the temporal extent of crop yield time series. While Cantelaube et al. (2004) have used time series ending around 2000, our analysis is based on time series ending 15 years later. This is an important factor, as winter wheat yields in many western European countries have flattened, roughly after 1995 (Brisson et al., 2010). As yield stagnation in France has been linked to heat stress during the grain filling period, this has not been the case in the UK (Hawkins et al., 2013). A number of variables after 1996 have been identified as potentially having had an influence on yield trend and variability, such as deep soil compaction, UV-B levels, under-drainage, seed rates and others (Knight et al., 2012). These factors might have masked as well the large-scale climate variability signal in yields. Indeed, when the time series of the UK yields are shrunk to the period before 2000, the same analysis provides substantially more skillful winter wheat prediction models, comparable to the one observed by Cantelaube et al. (2004). Additionally, the loss of skill in the UK longer time series might have been caused by non-stationarity in the NAO relationship with surface weather variables, especially w.r.t. winter precipitation (Comas-Bru and McDermott, 2014, Vicente-Serrano and Lopez-Moreno, 2008).

Varying skill of prediction models based on de-trended yield data depends strongly on manifestation of large-scale atmospheric variability at regional level, especially during the most sensitive growth stages of flowering and grain filling. The national level yield statistics (here used) can only reflect the yield production over large areas. In the main agricultural producers of Europe (such as France and Germany) different weather conditions can prevail over distant agricultural areas. Final crop yield estimates at national level might therefore contain mixed climate signal, which cannot be easily depicted by statistical analysis working at lower spatial resolution. Similar analysis at higher spatial scale might result in prediction models with substantially higher skills. Even though the high level of agro-management can mask the fingerprint of climate variability in crop yields (e.g. irrigation for grain maize), our analysis points to a significant influence of large-scale atmospheric variability on crop growth across Europe. The leading modes of the large-scale atmospheric variability can then be used to derive crop yield prediction models having moderate skill.

It is interesting to note that, in a regional application, the model explanatory power for winter wheat generally outperforms the one of a process-based crop model (SOM, Table S.1). Lower performance of the process-based approach might be related to several causes, such as the representation of relevant processes during the sensitive growth stages, spatial representation of crop varieties and the quality of input meteorological and soil data. In addition, the reliability of regional application of process based model is spatially highly dependent on the share of harvested area (Watson et al., 2014). Statistical approaches, such as the one here proposed, might therefore provide a robust framework to model national crop yields. This is surely appealing due to the substantially lower input data requirements in comparison to process based crop models. The model explanatory power for grain maize is, though, generally lower or comparable to the process based approach. The four large scale atmospheric indices are less efficient in predicting grain maize than the winter wheat yields due to higher importance of regional-to-local atmospheric phenomena during summer, which are better captured by the regional application of a process based crop model forced by observed surface climate variables. Generally, empirical studies using carefully selected surface climate variables as predictors for national crop yield resulted in comparable or higher proportion of explained inter-annual crop yield variability (e.g. Hernandez-Barrera et al., 2016, Hawkins et al., 2013, Brown, 2013). This is somehow an expected result, since large scale atmospheric variability can explain only a portion of regional-to-local surface climate variability.

Even though the main source of predictability has been observed in summer, there are regions where weather conditions during late autumn and winter importantly contribute to the skill of the prediction models for winter wheat. With improved stratosphere–troposphere coupling and atmospheric initial conditions, high skill has been observed in predicting the leading mode of circulation in the northern hemisphere winter circulation (Stockdale et al., 2015). Moreover, the skillful dynamical model predictions of the winter NAO have been extended to more than a year ahead (Dunstone et al., 2016). Since the seasonal predictability of large-scale atmospheric patterns is higher than the one of surface weather variables (e.g. precipitation) in Europe, seasonal crop yield prediction could benefit from the integration of derived statistical models exploiting the dynamical seasonal forecast of large-scale atmospheric circulation. Additionally, derived empirical models could be integrated into a hybrid crop yield forecasting framework, complementing a process based crop model. The skill of such framework remains to be assessed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for providing the data on large-scale atmospheric circulation indicators. Francisco J. Doblas-Reyes received funding from the European Commission's Seventh Framework Research Programme SPECS project (GA 308378).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.03.019.

Contributor Information

Andrej Ceglar, Email: andrej.ceglar@ec.europa.eu.

Marco Turco, Email: mturco@bsc.es.

Andrea Toreti, Email: andrea.toreti@ec.europa.eu.

Francisco J. Doblas-Reyes, Email: francisco.doblas-reyes@bsc.es.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Barnston A.G., Livezey R.E. Classification, seasonality, and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 1987;115:1083–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Biavetti I., Karetsos S., Ceglar A., Toreti A., Panagos P. PROC. SPIE 9229, Second International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment. 2014. European meteorological data: contribution to research, development, and policy support. [Google Scholar]

- Bladé I., Liebmann B., Fortuny D., van Oldenborgh G.J. Observed and simulated impacts of the summer NAO in Europe: implications for projected drying in the Mediterranean region. Climate Dyn. 2012;39:709–727. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson N., Gate P., Gouache D., Charmet G., Oury F.X., Huard F. Why are wheat yields stagnating in Europe? A comprehensive data analysis for France. Field Crops Res. 2010;119:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Brown I. Influence of seasonal weather and climate variability on crop yields in Scotland. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2013;57:605–614. doi: 10.1007/s00484-012-0588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantelaube P., Terres J.M., Doblas-Reyes F.J. Influence of climate variability on European agriculture – analysis of winter wheat production. Climate Res. 2004;27:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Casado M., Pastor M., Doblas-Reyes F. Euro-Atlantic circulation types and modes of variability in winter. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009;96:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva A., Rodríguez-Puebla C., Frías M.D., González-Reviriego N. Variability of extreme precipitation over Europe and its relationships with teleconnection patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014;18:709–725. [Google Scholar]

- Ceglar A., Toreti A., Lecerf R., Van der Velde M., Dentener F. Impact of meteorological drivers on regional inter-annual crop yield variability in France. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016;216:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Challinor A., Slingo J., Wheeler T., Craufurd P., Grimes D. Toward a combined seasonal weather and crop productivity forecasting system: determination of the working spatial scale. J. Climate Appl. Meteorol. 2003;42:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Challinor A., Watson J., Lobell D., Howden S., Smith D., Chhetri N. A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat. Climate Change. 2014;4:287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland W.S. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Bru L., McDermott F. Impacts of the EA and SCA patterns on the European twentieth century NAO-winter climate relationship. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2014;140:354–363. [Google Scholar]

- Deryng D., Conway D., Ramankutty N., Price J., Warren R. Global crop yield response to extreme heat stress under multiple climate change futures. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014;9:034011. [Google Scholar]

- Doblas-Reyes F., García-Serrano J., Lienert F., Pintó Biescas A., Rodrigues L. Seasonal climate predictability and forecasting: status and prospects. WIREs Climate Change. 2013;4:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Doblas-Reyes F., Pavan V., Stephenson D. The skill of multi-model seasonal forecasts of the wintertime North Atlantic Oscillation. Climate Dyn. 2003;21:501–514. [Google Scholar]

- Dunstone N., Smith D., Scaife A., Hermanson L., Eade R., Robinson N., Andrews M., Knight J. Skilful predictions of the winter North Atlantic Oscillation one year ahead. Nat. Geosci. 2016;9:809–814. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B., Hastie T., Johnstone I., Tibshirani R., Ishwaran H., Knight K., Loubes J.M., Massart P., Madigan D., Ridgeway G., Rosset S., Zhu J.I., Stine R.A., Turlach B.A., Weisberg S., Hastie T., Johnstone I., Tibshirani R. Least angle regression. Ann. Stat. 2004;32:407–499. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . 2016. Eurostat – Agriculture, forestry and fisheries database.http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed 30.01.16) [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra R.A., Podestá G.P., Messina C.D., Letson D., Dardanelli J., Guevara E., Meira S. A linked-modeling framework to estimate maize production risk associated with ENSO-related climate variability in Argentina. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001;107:177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Finger R. Evidence of slowing yield growth – the example of Swiss cereal yields. Food Policy. 2010;35:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Frías M., Herrera S., Cofi no A., Gutiérrez J.M. Assessing the skill of precipitation and temperature seasonal forecasts in Spain: windows of opportunity related to ENSO events. J. Climate. 2010;23:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno L., Ribera P., Iglesias R., Torre L.d.l., García Herrera R., Hernández Martín E. Identification of empirical relationships between indices of ENSO and NAO and agricultural yields in Spain. Climate Res. 2002;21:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.W. Integrating seasonal climate prediction and agricultural models for insights into agricultural practice. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B: Biol. Sci. 2005;360:2037–2047. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.W., Jones J.W., Kiker C.F., Hodges A.W. El Niño-Southern Oscillation impacts on winter vegetable production in Florida. J. Climate. 1999;12:92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins E., Fricker T.E., Challinor A.J., Ferro C.A., Ho C.K., Osborne T.M. Increasing influence of heat stress on French maize yields from the 1960s to the 2030s. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:937–947. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Barrera S., Rodriguez-Puebla C., Challinor A.J. Effects of diurnal temperature range and drought on wheat yield in Spain. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hurvich C.M., Tsai C.L. Bias of the corrected AIC criterion for underfitted regression and time series models. Biometrika. 1991;78:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Iizumi T., Luo J.J., Challinor A.J., Sakurai G., Yokozawa M., Sakuma H., Brown M.E., Yamagata T. Impacts of El Niño Southern Oscillation on the global yields of major crops. Nat. Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irannezhad M., Klöve B. Do atmospheric teleconnection patterns explain variations and trends in thermal growing season parameters in Finland? Int. J. Climatol. 2015;35:4619–4630. [Google Scholar]

- Kettlewell P.S., Stephenson D.B., Atkinson M.D., Hollins P.D. Summer rainfall and wheat grain quality: relationships with the North Atlantic Oscillation. Weather. 2003;58:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Khan J.A., Aelst S.V., Zamar R.H. Fast robust estimation of prediction error based on resampling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2010;54:3121–3130. [Google Scholar]

- Khan J., Van Aelst a., Zamar S. Robust linear model selection based on least angle regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2007;102:1289–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Knight S., Kightley S., Bingham I., Hoad S., Lang B., Philpott H., Stobart R., Thomas J., Barnes A., Ball B. Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board; 2012. Desk study to evaluate contributory causes of the current yield plateau in wheat and oilseed rape. Technical Report 502. [Google Scholar]

- Krichak S.O., Breitgand J.S., Gualdi S., Feldstein S.B. Teleconnection-extreme precipitation relationships over the Mediterranean region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014;117:679–692. [Google Scholar]

- Lobell D. Errors in climate datasets and their effects on statistical crop models. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013;170:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos R., Llasat M.C., Quintana-Seguí P., Turco M. Seasonal predictability of water resources in a Mediterranean freshwater reservoir and assessment of its utility for end-users. Sci. Total Environ. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos R., Turco M., Bedía J., Llasat M.C., Provenzale A. Seasonal predictability of summer fires in a Mediterranean environment. IJWF. 2015;24:1076–1084. [Google Scholar]

- MCYF - MAR Crop Yield Forecasting System . 2016. AGRI4CAST resource portal.http://agri4cast.jrc.ec.europa.eu/DataPortal/Index.aspx?.o=d (accessed 30.01.16) [Google Scholar]

- Meinke H., Hochman Z. Applications of Seasonal Climate Forecasting in Agricultural and Natural Ecosystems. Springer; 2000. Using seasonal climate forecasts to manage dryland crops in northern Australia – experiences from the 1997/98 seasons; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Moore F.C., Lobell D.B. Adaptation potential of European agriculture in response to climate change. Nat. Climate Change. 2014;4:610–614. [Google Scholar]

- Moore F.C., Lobell D.B. The fingerprint of climate trends on European crop yields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:2670–2675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409606112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B., Seneviratne S.I. Hot days induced by precipitation deficits at the global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:12398–12403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204330109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash J.E., Sutcliffe J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I – a discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970;10:282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J.E., Börgessen C.D., Elsgaard L., Palosuo T., Rötter R.P., Skjelvåg A.O., Peltonen-Sainio P., Börjesson T., Trnka M., Ewert F., Siebert S., Brisson N., Eitzinger J., van Asselt E.D., Oberfoster M., van der Fels-Klerx H.J. Changes in time of sowing, flowering and maturity of cereals in Europe under climate change. Food Addit. Contam. Part A: Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2012;29:1527–1542. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2012.712060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepler A.S., Díaz L.B., Prodhomme C., Doblas-Reyes F.J., Kumar A. The ability of a multi-model seasonal forecasting ensemble to forecast the frequency of warm, cold and wet extremes. Weather Climate Extremes. 2015;9:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Persson T., Bergjord A.K., Höglind M., Persson T., Bergjord A., Höglind M. Simulating the effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation on frost injury in winter wheat. Climate Res. 2012;53:43. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J., Cane M., Rosenzweig C. ENSO, seasonal rainfall patterns and simulated maize yield variability in Zimbabwe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1998;90:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Prodhomme C., Batte L., Massonnet F., Davini P., Bellprat O., Guemas V., Doblas-Reyes F. Benefits of increasing the model resolution for the seasonal forecast quality in EC-Earth. J. Climate. 2016;29:9141–9162. [Google Scholar]

- Prodhomme C., Doblas-Reyes F., Bellprat O., Dutra E. Impact of land-surface initialization on sub-seasonal to seasonal forecasts over Europe. Climate Dyn. 2015:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada B., Vautard R., Yiou P., Hirschi M., Seneviratne S.I. Asymmetric European summer heat predictability from wet and dry southern winters and springs. Nat. Climate Change. 2012;2:736–741. [Google Scholar]

- Scaife A., Arribas A., Blockley E., Brookshaw A., Clark R., Dunstone N., Eade R., Fereday D., Folland C., Gordon M. Skillful long-range prediction of European and North American winters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014;41:2514–2519. [Google Scholar]

- Sepp M., Saue T. Correlations between the modelled potato crop yield and the general atmospheric circulation. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012;56:591–603. doi: 10.1007/s00484-011-0448-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shongwe M.E., Ferro C.A., Coelho C.A., Jan van Oldenborgh G. Predictability of cold spring seasons in Europe. Mon. Weather Rev. 2007;135:4185–4201. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert S., Ewert F. Future crop production threatened by extreme heat. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014;9:041001. [Google Scholar]

- Soares M.B., Dessai S. Exploring the use of seasonal climate forecasts in Europe through expert elicitation. Climate Risk Manage. 2015;10:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale T.N., Molteni F., Ferranti L. Atmospheric initial conditions and the predictability of the Arctic Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42:1173–1179. 2014GL062681. [Google Scholar]

- Toreti A., Xoplaki E., Maraun D., Kuglitsch F.G., Wanner H., Luterbacher J. Characterisation of extreme winter precipitation in Mediterranean coastal sites and associated anomalous atmospheric circulation patterns. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010;10:1037–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Träger-Chatterjee C., Müller R.W., Bendix J. Analysis and discussion of atmospheric precursor of European heat summers. Adv. Meteorol. 2014:2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimba R., Edmeades G.O., Millner J.P., Kemp P.D. The effect of planting date on maize grain yields and yield components. Field Crops Res. 2013;150:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano S., Lopez-Moreno J. Nonstationary influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation on European precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008;113:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano S.M., García-Herrera R., Barriopedro D., Azorin-Molina C., López-Moreno J.I., Martín-Hernández N., Tomás-Burguera M., Gimeno L., Nieto R. The Westerly Index as complementary indicator of the North Atlantic oscillation in explaining drought variability across Europe. Climate Dyn. 2016;47:845–863. [Google Scholar]

- Watson J., Challinor A.J., Fricker T.E., Ferro C.A. Comparing the effects of calibration and climate errors on a statistical crop model and a process-based crop model. Climate Change. 2014;132:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Weisheimer A., Doblas-Reyes F.J., Jung T., Palmer T. On the predictability of the extreme summer 2003 over Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011;38 [Google Scholar]

- Wilks D. Elsevier; 2006. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Yiou P., Nogaj M. Extreme climatic events and weather regimes over the North Atlantic: when and where? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004;31:1–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.