SUMMARY

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses), such as Zika, chikungunya, and West Nile virus (WNV), pose as continuous threats to emerge and cause large epidemics. Often these events are associated with novel virus variants optimized for local transmission that first arise as minorities within a host. Thus, the conditions that regulate the frequency of intrahost variants are important determinants of emergence. Here we describe the dynamics of WNV genetic diversity during its transmission cycle. By temporally sampling saliva from individual mosquitoes, we demonstrate that virus populations expectorated by mosquitoes are highly diverse and unique to each feeding episode. After transmission to birds, however, most genetic diversity is removed by strong purifying selection. Further, transmission of potentially mosquito-adaptive WNV variants is strongly influenced by genetic drift in mosquitoes. These results highlight the complex evolutionary forces that a novel virus variant must overcome to alter infection phenotypes at the population level.

eTOC Blurb

Grubaugh et al. describe how a single infected mosquito can transmit different virus populations during each blood feeding, highlighting the incredible amount of adaptive potential that exists in nature. This diversity, however, is rapidly removed during infection of a vertebrate host, which acts to maintain virus fitness.

INTRODUCTION

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses), especially those transmitted by mosquitoes, can have significant public health and societal impacts. For example, the recent epidemics of Zika and chikungunya viruses in the Americas likely led to more than a million human infections with some leading to unexpected and severe disease (Fauci and Morens, 2016). These sudden emergences of outbreaks and pathogenesis, however, are not unique among arboviruses. Prior to the 1990s, West Nile virus (WNV; Flavivirus; Flaviviridae) outbreaks were generally mild and small in scale. Then WNV epidemics in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin shifted our perspective because they 1) were often large, 2) were associated with neurological symptoms and high case-fatality rates, and 3) occurred in temperate regions (Kramer et al., 2008). The increasing burden caused by WNV continued after it was first detected in New York City in 1999 and rapidly spread throughout North and South America. Several adaptive mutations to the viral RNA sequence contributed to the emergence of WNV, including separate mutations that increased pathogenesis in birds (Brault et al., 2007) and increased fitness in Culex mosquitoes (Ebel et al., 2004; Moudy et al., 2007). While genetic diversity of arboviruses can clearly provide opportunities for adaptation, the specific conditions that influence the selection of new emergent strains are not entirely clear.

The dynamics of arbovirus evolution during transmission between divergent vectors and hosts are critical for determining how and when new viruses are selected. Because the Culex mosquitoes and birds that are involved in WNV transmission can be manipulated in the lab, experimental evolution studies using this platform led to several important insights about arbovirus evolution. In mosquitoes, WNV genetic diversity is generated in part by RNA-interference (RNAi) mediated diversifying selection (Brackney et al., 2009; Brackney et al., 2015), randomly rearranged by bottlenecks (Ciota et al., 2012; Grubaugh et al., 2016), and persists due to relatively weak purifying selection (Jerzak et al., 2005; Jerzak et al., 2007; Jerzak et al., 2008). Despite the rapid accumulation of genetic diversity during mosquito infection, long term evolution of WNV, like other arboviruses, is slow compared to many single-host viruses (Woelk and Holmes, 2002). It is hypothesized that this is due to fitness trade-offs (Deardorff et al., 2011) and strong purifying selection during transmission to birds (Grubaugh et al., 2015). The temporal aspects of WNV evolution from a single transmission lineage (i.e., from an individual mosquito to a bird), however, have not been examined.

Accordingly, we sought to determine how WNV populations expectorated by a single mosquito change through time, and how these populations are altered during the course of subsequent avian viremia. By temporally sampling mosquito saliva and bird serum and reconstructing virus populations using next-generation sequencing (NGS), we thus describe the dynamics of virus evolution during transmission. Our data suggest that mosquitoes can transmit unique WNV populations during each feeding episode and mutations that confer fitness advantages may be lost in vivo due to strong genetic drift. In addition, most virus genetic diversity that accumulates during mosquito infection is selectively purified during transmission, leading to preservation of the original consensus amino acid sequence during acute bird infection. Therefore, we experimentally demonstrate most WNV genetic change occurs during transmission and that purifying selection during replication in the vertebrate host is primarily responsible for the slow rates of evolution. These findings highlight the random and selective hurdles that prevent potentially adaptive mutations from becoming dominant during mosquito-borne transmission.

RESULTS

Temporal evolution of West Nile virus populations within mosquito saliva

To collect WNV populations expectorated from mosquito saliva over time, Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. tarsalis mosquitoes (n = 50 each species) engorged with WNV-spiked blood were housed individually and were offered sucrose-soaked filter paper as their only sugar source (Figure 1A, modified from (Hall-Mendelin et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2015)). Nucleic acid from mosquito saliva expectorated onto sucrose-soaked filter paper was collected every two days and tested for the presence of WNV RNA and mosquito mitochondrial DNA (abundant sequences detected in mosquito saliva, used to determine if the mosquito expectorated saliva onto the card). A higher proportion of Cx. tarsalis that expectorated saliva could transmit WNV than Cx. quinquefasciatus (Figure 1B). This method of exploiting sugar-feeding for the collection of virus RNA from mosquito saliva was comparable to the standard in vitro transmission assay (i.e., saliva collected by oil-filled capillary tubes) in terms of WNV RNA quantity (Figure S1A and S1D), detection of mixed genotypes within a population (Figure S1B–C), and generating equal distributions of reads across the WNV genome (Figure S1F). A drawback to using filter paper to collect expectorated WNV is that it is more likely to yield a smaller percentage of WNV reads (Figure S1E), requiring more reads to produce similar coverage depths to WNV recovered from capillary tubes (Table S1–S2).

Figure 1. Genetically unique West Nile virus populations expectorated during each feeding episode.

(A) Saliva from individual mosquitoes housed in 50 mL conical tubes were collected temporally by allowing them to feed on sucrose-soaked filter paper.

(B) Sucrose-soaked filter paper was offered to and removed from WNV-exposed Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. tarsalis mosquitoes (n = 50 each species) every 2 days post bloodfeeding (dpbf). Filter paper were screened for WNV RNA by qRT-PCR. WNV-negative samples were assayed for Culex mitochondrial DNA by qPCR to differentiate between true negatives and mosquitoes that did not expectorate saliva onto the filter paper. Saliva RNA from three of each mosquito species with detectable WNV RNA at 8, 14, and 18 dpbf (arrows) were prepared for NGS.

(C) Temporal changes to WNV genetic distance (mutations per coding sequence) from expectorated saliva (e.g. “Cx.q(a)”, Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquito replicate (a)).

(D) Genetic divergence (FST) of the WNV populations recovered from mosquito saliva were ompared to the input virus, cumulatively between feeding episodes at specific time points (same individual), and between replicates (different individuals) within a time point (circles). This figure was created using Figure S2.

(E) Divergences (mean with 95% CI) of WNV populations expectorated by the same mosquitoes between feeding episodes (time points) were compared (unpaired t test; ns, not significant) to the divergences between virus populations expectorated by different mosquitoes at the same time point.

(F) Virus variants detected at least once > 0.25 frequency were tracked individually by frequency from the bloodmeal input virus (0 dpbf) and during each mosquito feeding episode. Red lines indicate synonymous variants and black lines indicate nonsynonymous variants. Variants above the dotted line at 0.5 frequency are consensus changes.

(G) The proportion of variants (mean with 95% CI) detected in the bloodmeal and from subsequent feeding episodes (conservation) were tracked to determine the relatedness of virus populations.

RNA from three individuals of each species that were positive for WNV RNA 8, 14, and 18 days post bloodfeeding were analyzed by NGS to describe the dynamics of arbovirus evolution from individual mosquitoes (Figure 1, Figure S2, Table S1). The median WNV coding sequence coverage depth was 1,260x (range: 620–65,569x). To reduce potential biases introduced by coverage depth variation, all intrahost analysis of virus population structure was limited to coding sequence variants of ≥ 0.01 frequency.

The genetic distances (i.e., mutations per coding sequence) from virus populations expectorated by individual mosquitoes were highly variable (Figure 1C, Figure S2A). We estimated the fixation index (FST) of WNV obtained from saliva samples to determine the degree of genetic divergence between virus populations transmitted by the same mosquito during different feeding episodes. Transmitted virus diverged from the input WNV, but not in a continuous manner (Figures 1D and S2F-H). The degree of divergence from the same mosquito between time points was similar to the divergence between different mosquitoes at the same time point (P > 0.05, unpaired t test, Figure 1E). We speculated that if the expectorated virus populations were mostly unrelated between feeding episodes, then prominent variants, including consensus changes, would also be different. From an individual mosquito, both synonymous and nonsynonymous variants detected at a frequency ≥ 0.25 dramatically fluctuated between the expectorated populations (Figure 1F). In fact, we recovered virus populations with different consensus sequences between several sequential saliva collections.

We used the proportion of same variants detected between populations (variant conservation) as a method to estimate the relative bottleneck size. A severe bottleneck was detected between the input virus and the mosquito saliva 8 days post bloodfeeding as evident by the very small proportion (~5–10%) of both synonymous and nonsynonymous variant conservation (Figure 1G). Variant conservation increased at later time points, suggesting that more viruses can pass through the barriers over time (i.e., the bottlenecks became larger).

Compared to WNV populations recovered from saliva expectorated into capillary tubes 14 days post bloodfeeding (Table S2), the filter paper-derived populations had a higher proportion of intermediate frequency (0.05 to 0.95) variants (31% compared to 18%, Figure S2C) and were more complex (Figure S2E), but genetic distances were similar (Figure S2D). This led us to speculate that some of the viruses collected from filter paper were composed of multiple populations. Therefore, we combined two and three NGS data sets from saliva (both within and between species) collected by capillary tubes to be used as comparison and repeated our analysis, as above. We found that distance did not change when the populations were mixed and remained similar to filter paper WNV populations (Figure S2D). The complexities of the mixed populations, however, increased and were more similar to the higher complexity WNV populations collected on filter paper (Figure S2E), suggesting that some mosquitoes expectorated multiple virus populations during sugar feeding within the two days of access to the sucrose-soaked filter paper. During our validation experiments, the proportions of two distinct WNV genotypes from saliva collected by filter paper and capillary tubes (same mosquito) were similar likely because 1) the sucrose-soaked filter paper was only offered for 6 hours (minimizing the number of saliva expectorations) and 2) the viruses were of equal fitness (minimizing the influence of selection on our measurements, Figure S1B–C).

Convergent evolution and advantageous virus mutations

Four nonsynonymous consensus nucleotide substitutions (> 0.5 frequency), C1883T (amino acid substitution E-S306L), C5480T (NS3-T290I), A6319T (NS3-T570S), and A10169G (NS5-E350G), were detected in saliva from two or more individual mosquitoes (Figure 2A, Table S3). The input virus population was also examined for the presence of these variants to help determine if their rise to high frequency in multiple mosquitoes was due to selection (convergent evolution) or chance (genetic drift). The nucleotide variant C1883T was present in 3% of the input population. Nucleotide variants C5480T, A6319T, and A10169G were not detected in the VPhaser2-filtered data, but analysis of the pre-filtered alignment file showed that the variants were present in 0.5–1% of the input virus sequences from ~13,000–24,000x coverage. About all possible nucleotides, however, were detected within the range of 0.1–1% frequency at each site from the input virus. Therefore, since C5480T, A6319T, and A10169G were detected within the expected range of NGS errors and were filtered-out from the input virus population, the presence of these consensus changes from multiple mosquitoes were more likely to be the product of de novo mutation and convergent evolution rather than genetic drift of already present variants.

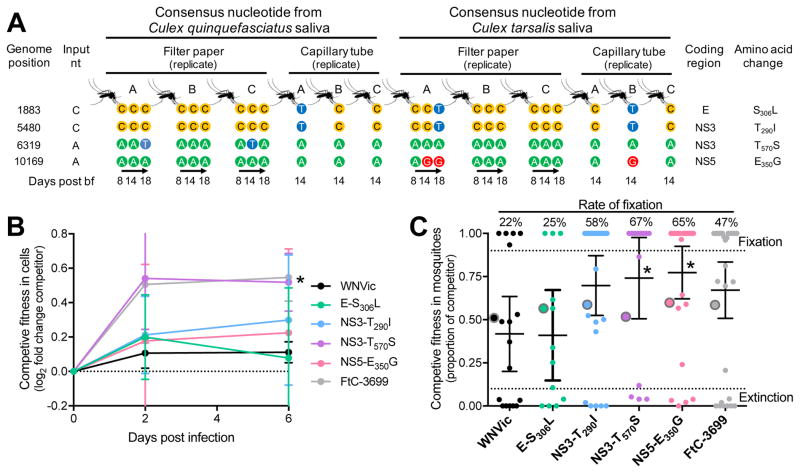

Figure 2. Evidence for convergent evolution of mutations with fitness advantages in mosquitoes.

(A) Nonsynonymous consensus sequence changes hypothesized to be the result of convergent evolution were detected in saliva from two or more individual mosquitoes using both saliva sampling techniques (sucrose-soaked filter paper and mineral oil-filled capillary tubes). Each colored circle represents the consensus nucleotide recovered from a saliva sample at a given time. The frequencies of each variant are listed in Table S3.

(B–C) Each mutation was engineered into a WNV infectious clone (WNVic, Table S4) for competitive fitness studies. The WNVic, the potentially mosquito-adapted mutations engineered into the clones, and the natural WNV FtC-3699 isolate used in this study (competitors) were equally mixed individually with a WNV reference and used for co-infection of (B) Cx. tarsalis cells and (C) Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. The proportion of competitor genomes relative to the reference during infection were determined by quantitative sequencing. WNVic and FtC-3699 are equal and increased fitness controls, respectively, compared to the reference.

(B) Fitness was determined as the fold change (mean with 95% CI) in proportion of competitor genomes from cell culture supernatant compared to the inoculum (n = 4 each time point). Dataabove the dotted line at 0 have an increased proportion. * The fold change increase of NS3-T570S over the reference WNV was significantly higher than the fold change of WNVic (P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

(C) The proportion of each competitor (mean with 95% CI) was determined from individual mosquito bodies at 17 dpbf and was compared to each inoculum (large circles with grey borders). The dotted lines at 0.1 and 0.9 frequency indicate the range of high accuracy. Fixation and extinction indicate that 100% and 0%, respectively, of the sequenced nucleotides were from the competitor virus. * P < 0.05 compared to WNVic, Kruskal-Wallis-Dunn’s.

To test the fitness associated with each potentially selected mutation, we used site-directed mutagenesis to engineer each into a WNV infectious clone (WNVic) for direct competition against a genetically marked WNV reference during co-infection (Table S4). In Cx. tarsalis cells, the mutant virus A6319T (NS3-T570S) had a significant competitive fitness advantage over the WNVic relative to the reference virus at 6 dpi (P < 0.05, unpaired t test; Figure 2B). In orally-infected Cx. quinquefasciatus bodies, A6319T (NS3-T570S, and A10169G (NS5-E350G) had significant competitive advantages 17 days post bloodfeeding (P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis-Dunn’s, Figure 2C). Since the mutant C1883T (E-S306L) 1) had similar fitness to the WNVic relative to the reference virus during in vitro and in vivo competitions, 2) was present in the bloodmeal at 3%, and 3) only went to high frequency when paired with another variant, we suspect that its detection at high frequency in some mosquitoes may have been the result of genetic drift and hitchhiking. A caveat is that C1883T may impact fitness when combined with one or more of the other mutations. In addition, the genome of WNVic used as the genetic backbone is only 99.3% identical to WNV (FtC-3699) used in the transmission experiments. Consequently, there could be cis and trans-acting fitness impacts not captured in our competition assays.

Intrahost virus genetic diversity during mosquito-borne transmission and bird infection

We created a model to understand how WNV evolves during natural transmission by allowing mosquitoes capable of expectorating WNV to feed on young chickens. Sucrose-soaked filter paper was used to detect WNV RNA from mosquito saliva at 6–8 days post bloodfeeding and to identify mosquitoes capable of transmitting virus. WNV-transmitting mosquitoes were marked with fluorescent powder and transferred to cartons with 8–10 unexposed mosquitoes of the same species to facilitate bloodfeeding (Figure 3A). We characterized virus populations from the saliva (collected by capillary tubes) of Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. tarsalis mosquitoes (n = 3 each species) just after feeding and from bird serum 1 to 4 days post infection (dpi). Cx. tarsalis saliva contained more WNV GE than Cx. quinquefasciatus saliva, which may have led to higher avian viremias (Figure 3B) and some differences in population structure after transmission (Figure S3A–C). The overall WNV population trends were similar between mosquito species; therefore, replicates from each species were combined to determine the generalized patterns of virus genetic diversity during Culex transmission (Figure 3C–E). Upon transmission from a mosquito to a bird, WNV genetic distance rapidly decreased and then remained relatively stable during the bird viremic period (Figure 3C–D). Most variants in mosquito saliva were lost or removed by selection in birds (Figures 3E and S3D-F). WNV in birds accumulated variants > 0.01 frequency at a rate of 2.66–5.22 × 10−5 substitutions/coding sequence site/day of bird infection.

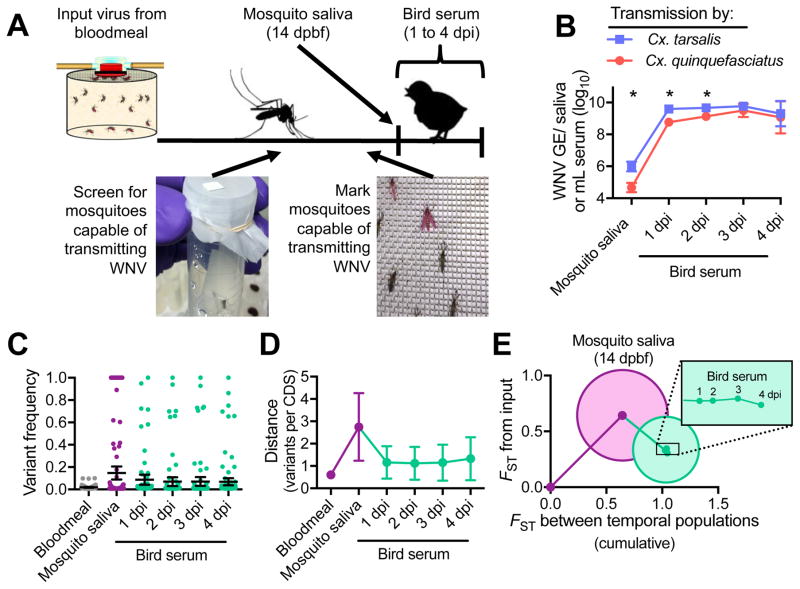

Figure 3. West Nile virus genetic diversity decreases after mosquito transmission to birds, and remains stable.

(A) Experimental transmission of WNV from a single mosquito to a bird. WNV-exposed mosquitoes were screened for the presence of WNV RNA in their saliva by collecting sucrose-soaked filter paper offered to the mosquitoes from 6–8 dpbf. Mosquitoes potentially capable of transmitting WNV were marked with fluorescent powder at 13 dpbf and transferred to cartons with 8–10 unexposed mosquitoes of the same species to facilitate bloodfeeding on birds 14 dpbf. Virus populations were sequenced from mosquito saliva collected by capillary tubes immediately after bloodfeeding and from bird serum 1 to 4 dpi.

(B) The quantity of WNV GE per saliva sample and mL bird serum determined by qRT-PCR was compared (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s corrections; *, P < 0.05) between experimental transmission involving Cx. tarsalis and Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (n = 3 each species).

(C–E) The experimental replicates from both mosquito species were combined (mean with 95% CI) to analyze the general changes to (C) mean variant frequencies and distributions, (D) genetic distances (mutations per coding sequence), and (C) divergences (FST) between populations during mosquito-borne transmission and subsequent bird infection.

(E) Circles represent the divergences between biological replicates. Figure was created using Figure S4F–H.

Examination of the fate of individual virus variants during transmission to birds and subsequent acute infection (Figure 4A) showed that 5 of 7 synonymous consensus changes (Figure 4B) and ~50% of the total synonymous variants were conserved (Figure 4C, which increased to ~90% during peak viremia). The two synonymous consensus changes lost were accompanied by a nonsynonymous mutation. In contrast, only about 10% of the nonsynonymous variants were conserved (Figure 4C), including only 1 of 6 nonsynonymous consensus changes (Figure 4B). Moreover, an estimate of selection, dN/dS, supports that purifying selection increased (i.e., smaller dN/dS ratios) during WNV infection of birds (Figure 3D). Purifying selection was the strongest in the structural protein coding region during replication in birds, but was not regionally different in mosquitoes (Figure 4D). These results suggest that the WNV populations do not encounter severe bottlenecks during transmission to birds and that evolution is mainly determined by selection.

Figure 4. Relaxed bottlenecks and strong purifying selection during bird infection.

(A) Individual virus variants from combined replicates per group were plotted by their frequency and WNV genome position (yellow, structural protein region; purple, non-structural protein region). Red dots indicate synonymous mutations and black dots indicate nonsynonymous mutations.

(B) Virus consensus sequence changes (> 0.5 frequency, dotted line) detected in the mosquito saliva were tracked during transmission to birds. No new consensus changes arose during bird infection.

(C) The proportion of variants (mean with 95% CI) detected in subsequent populations (conservation) were tracked from the mosquito bloodmeal through transmission to birds.

(D) The strength of host selection on virus populations, estimated by dN/dS (mean with 95% CI), was tracked during transmission and bird infection. dN/dS values < 1 (dotted line) represent strong purifying selection.

Virus evolution through multiple transmission cycles

We initiated three independent lineages of multiple cycles of WNV transmission (i.e., bloodmeal-mosquito-chicken-mosquito-chicken) to further assess the dynamics of virus population diversity during rapidly changing environments (Figure 5). We sequenced WNV populations from bird serum on the days of transmission to mosquitoes (2 dpi). WNV GE from Cx. quinquefasciatus saliva (14 days post bloodfeeding) trended towards undetectable levels beyond the first round of transmission (Figure S4). In addition, mosquito mortality after bloodfeeding on viremic chicks was positively correlated with the WNV GE/mL bird serum (Pearson r = 0.7919, P < 0.05, Figure 6). Mortality was not different, however, between unexposed mosquitoes and those that ingested blood spiked with WNV from an artificial membrane feeder. Therefore, the groups of mosquitoes that were most likely to become infected and transmit virus (i.e., fed on birds with higher viremias) were also the most likely to die before they could transmit. The majority of the surviving mosquitoes had < 104 WNV genome equivalents (GE) per expectorated saliva sample, and while that was sufficient to infect birds during bloodfeeding, it was insufficient for our unbiased NGS approach. Thus, only WNV populations from bird serum were analyzed through multiple transmission cycles.

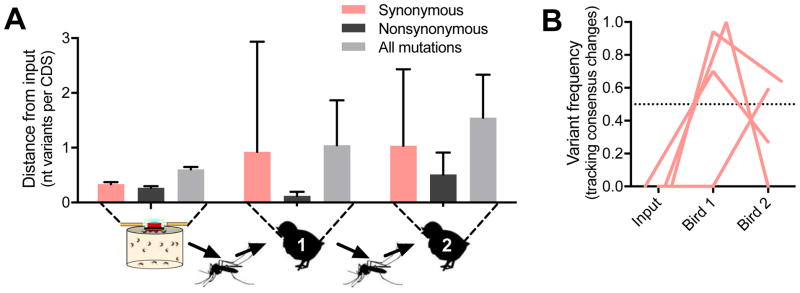

Figure 5. Strong purifying selection and genetic drift shape West Nile virus populations during multiple rounds of transmission.

(A) Two rounds of WNV transmission were preformed using Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes 14 dpbf and chicks 2 dpi (n = 3 independent lineages). Virus populations were sequenced from the bird serum, but sufficient WNV could not be recovered from all of the saliva collected from mosquitoes involved in transmission. Genetic distance (mean with 95% CI) was calculated from the input bloodmeal virus and each infected bird.

(B) Frequencies of the consensus changing variants (n = 4, all synonymous) detected during the two rounds of transmission were independently tracked. Variants above the dotted line at frequency 0.5 are consensus changes.

Figure 6. Chick viremia impacts survival of bloodfed Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes.

(A–B) Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes that fed upon WNV-spiked blood from a membrane feeder (2 replicates, 50 mosquitoes each replicate), birds previously exposed to mosquito feeding but that remained uninfected (3 birds, 20–30 mosquitoes each replicate), and mosquito-infected birds (7 birds [shown individually], 20–50 mosquitoes each replicate) were housed in individual 50 mL conical tubes.

(A) Mosquito survival was monitored every 2 dpbf.

(B) A curve comparison of mosquito survival was made from each infected bird to the uninfected birds to calculate a log-rank hazard ratio. The hazard ratios of mosquito survival from each comparison were then plotted with the quantity of WNV in the mosquito bloodmeal (WNV GE/mL bird serum). There was a significant positive linear correlation between the hazard ratio and the WNV GE/mL in the bird serum (Pearson r = 0.7919, r2 = 0.6271, P = 0.0338).

The WNV populations accumulated 0.5 mutations per coding sequence (0–1.5 95% CI) per round of bird infection (Figure 5A). Only a small proportion of the mutations that accumulated during chick infection were nonsynonymous (pN = 0.26, 0.02–0.49 95% CI), similar to experimental WNV infection of wild birds (pN = 0.33–0.46 (Grubaugh et al., 2015)), but significantly lower than the random expectation (pN = 0.76, P < 0.5, Wilcoxon signed rank test). Four consensus changes in birds were detected during the three independent transmission lineages, all of which were synonymous mutations, and the frequencies varied between birds within a lineage (Figure 5B).

DISCUSSION

Temporal sampling of expectorated virus populations from individual mosquitoes

In this study, we characterized WNV populations in expectorated mosquito saliva through time and during transmission to birds. A primary technical hurdle was to devise a method to repeatedly collect saliva from individual mosquitoes. Most techniques collect saliva as an endpoint and the mosquitoes are subsequently destroyed. As a result, different groups of mosquitoes were required to assess temporal changes to virus transmission (e.g., (Ebel et al., 2004; Kilpatrick et al., 2008)) or evolution (e.g., (Brackney et al., 2011; Ciota et al., 2012)). We adapted previously developed methods to detect virus from mosquito saliva by exploiting their requirements for sugar feeding (Hall-Mendelin et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2015). By allowing WNV-exposed mosquitoes to feed on sucrose-soaked filter paper (Figure 1A), we noninvasively collected and sequenced WNV populations from individuals over time. We found that the amount of WNV collected from sucrose-soaked filter paper was comparable to the standard in vitro transmission assay (i.e., saliva collected by capillary tubes, Figure S1). We could therefore determine when a mosquito could start to transmit virus (i.e., its extrinsic incubation period, Figure 1B) and track the changes to expectorated virus populations between feeding episodes.

Mosquitoes can transmit unique virus populations during each feeding episode

We found that mosquitoes transmit unique WNV populations during each feeding episode. Several lines of evidence support this observation. 1) WNV genetic distances were highly variable between saliva collections (Figure 1C). 2) Virus populations were just as divergent between feeding episodes from an individual mosquito as they were among different individual mosquitoes (Figure 1D–E). 3) Different consensus sequences were recovered between feeding episodes (Figure 1F). The prominent differences in genetic composition between the sugar feeding episodes 4–6 days apart suggests that the virus populations will also be highly divergent between bloodmeals (Culex quest for blood every 5–10 days (Reisen et al., 2006)). Considering that mosquitoes can take many bloodmeals during their lifetime, these data provide evidence for the large amount genetic diversity, and concomitant adaptive potential, that can be generated and potentially transmitted by a single competent mosquito vector.

Genetic drift during systemic mosquito infection randomly generates tissue- and saliva-specific virus subpopulations (Ciota et al., 2012; Forrester et al., 2012; Grubaugh et al., 2016; Lequime et al., 2016). The processes of virus salivary gland infection and escape may provide a model to describe how genetic drift shapes virus populations before each feeding episode. From a single focus in the salivary gland, WNV spreads to infect every cell (Girard et al., 2004). Superinfection exclusion can prevent the continuous movement of viruses between cells (Zou et al., 2009) and may create distinct and isolated WNV subpopulations. Mature virions in the cytoplasm are transported by intracellular vacuoles and/or are directly released into the acinus, the holding place for saliva proteins (Takahashi and Suzuki, 1979). During the course of infection, WNV induces cellular apoptosis and disorganizes gland structures (Girard et al., 2007), which may lead to temporal changes to the cells actively contributing virus into the acinus. Inside of the acinus, WNV particles form paracrystalline arrays that are likely transmitted as a group (Girard et al., 2007). Once the saliva is expectorated, then the entire process repeats with a new set of viruses. This model implies that the dynamic processes of salivary gland infection and escape, which potentially includes intercellular bottlenecks, different cells releasing virus into the acinus, and the formation of virus particle arrays, contributes to different virus subpopulations formed each time the acinus is reseeded.

Balance between selection and drift within mosquitoes

We detected three consensus WNV amino acid changes, NS3-T290I, NS3-T570S, and NS5-E350G, from the saliva of multiple mosquitoes that did not appear to be a part of the input virus population (Figure 2A, Table S3) suggesting that convergent evolution may occur in mosquitoes. The competitive fitness advantage of the mutant viruses relative to a reference WNV in Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (Figure 2C) further suggests that some or all of these alleles were positively selected. Despite the evidence for selection, their frequency of occurrence was highly variable and they became extinct in some individuals during the competitive fitness assays. This is almost certainly due to the bottlenecks that occur during systemic mosquito infection, and may also indicate how they were transiently detected from individual mosquitoes between feeding episodes (Figure 2A). For example, when the effective population size (Ne) is small, the selection coefficient (s) must be very large for any de novo mutation to become dominant (i.e., Nes ≫ 1). Hence it is likely that s for the NS3-T290I, NS3-T570S, and NS5-E350G mutations was large enough so that their occurrence is greater than what would be expected by chance, but not large enough to consistently overcome Ne. These data highlight the dynamic interplay between selection and drift within mosquitoes, and demonstrate why arbovirus mutations with large enough s to displace the ancestral genotype are rare (e.g., chikungunya virus E1-A226V (Stapleford et al., 2014; Tsetsarkin et al., 2007) and WNV E-A159V (Ebel et al., 2004; Moudy et al., 2007)).

Strong purifying selection during mosquito-to-bird transmission

While we previously hypothesized that WNV genetic diversity produced within mosquitoes would be rapidly removed during transmission to birds due to fitness trade-offs (Deardorff et al., 2011; Grubaugh et al., 2016) and strong purifying selection (Grubaugh et al., 2015; Jerzak et al., 2005; Jerzak et al., 2007; Jerzak et al., 2008), this experiment demonstrates the loss of WNV genetic diversity using a model transmission cycle (Figures 3 and 4). Furthermore, in contrast to mosquito infection, we provide evidence that Ne remained large (i.e., weak bottlenecks, Figure 4C) during transmission to birds which allowed evolution to be primarily influenced by selection and not drift. Consistent with this scenario, we found that a much larger proportion of synonymous mutations (~50%) were conserved during transmission than nonsynonymous (~10%). Purifying selection remained strong during the bird viremic period (Figure 4D), conserving virus population structure (Figure 3E) and removing de novo nonsynonymous mutations. This confirms that WNV replication in birds is important for maintaining population fitness through the removal of deleterious mutations.

An important caveat to the mosquito-to-bird transmission experiments is the use of young chickens that presumably lack fully developed immune systems, which may alter WNV selection. We previously compared WNV populations during replication in young chickens and three species of adult, wild-caught birds important for enzootic WNV transmission (American crows, house sparrows, and America robins (Grubaugh et al., 2015)). While we detected host-dependent impacts of WNV population structures, the most prominent observation, that purifying selection was strong, was consistent across avian species, including chicks. Therefore, we propose that young chickens are a suitable model to study generalized patterns of WNV evolution. It would be interesting, however, to preform transmission experiments involving different wild bird species to examine some of the ecological nuances of WNV evolution.

Slow rates of WNV evolution during multiple rounds of transmission

To enhance our predictions about virus evolution during transmission, we extended our model through two rounds of mosquito-to-bird transmission (Figure 5). The accumulation of ~ 0.5 mutations per WNV transmission cycle again highlights the slow rates of arbovirus evolution. Furthermore, between each round of transmission, the frequency synonymous mutations greatly fluctuated (Figure 5B) and most of the nonsynonymous mutations were removed (Figure 5A), indicating the strong presence of genetic drift and purifying selection, respectively. Others have documented that arbovirus variants generated within the vertebrate can also be removed during transmission to mosquitoes (Sessions et al., 2015; Sim et al., 2015). Combined, there is substantial in vivo evidence demonstrating that host cycling of arboviruses restricts genetic diversity likely because almost all arbovirus mutations impact fitness.

An interesting observation from our transmission experiments was the detection of chick viremia-dependent mosquito mortality post bloodfeeing (Figure 6). For our experiments, this finding was important because it greatly reduced our capacity to sustain WNV transmission and limited our conclusions about WNV evolution during host cycling. From a natural transmission perspective, this finding may suggest that factors (e.g., virus genetics and host response) increasing viremia in birds may have a cost of decreased survival, and therefore decreased WNV transmission, in mosquitoes. Others have reported that the lifespan of Cx. quiquefasciatus and Cx. tarsalis mosquitoes decreased upon exposure to WNV (Alto et al., 2014) and western equine encephalitis virus (Mahmood et al., 2004), respectively, and that these interactions may be dose-dependent (Lee et al., 2000). Unlike those studies, however, we did not detect significant changes to the survival of Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes upon exposure to WNV via artificial membrane filters. Rather, significant reductions in mortality were only noted after obtaining a bloodmeal from viremic chicks, which were correlated with viremia. These results certainly require further experimentation to define mosquito-pathogenic mechanisms and assess whether the outcomes are generalizable across different virus, mosquito, and host species.

Conclusions

The capacity to quantify and analyze the vast pool of genetic diversity in RNA virus populations has only recently been developed. It is now clear that the genetic composition of WNV populations differ greatly between individual mosquitoes (Brackney et al., 2011; Grubaugh et al., 2016; Jerzak et al., 2005). In this study, we clearly demonstrate how WNV populations transmitted by individual mosquitoes dramatically change during the life of the mosquito. This within-individual variability in transmitted WNV populations, applied across the thousands of potentially infected mosquitoes within a transmission focus leads to enormous opportunities for individual variants to emerge because 1) there are a vast array of variants generated and 2) they are transmitted along with a relatively restricted subset of competitors that may interfere with their emergence. Despite this, arbovirus evolution during natural transmission is slow (Woelk and Holmes, 2002). It was previously predicted that the low accumulations of amino acid substitutions were due to antagonistic pleiotropy where beneficial mutations in mosquitoes are detrimental in vertebrates (and vice versa) (Holmes, 2003). Using a model transmission cycle, we experimentally demonstrated that the relative fitness declines associated with WNV replication in mosquitoes (Deardorff et al., 2011; Grubaugh et al., 2016) actually lead to the selective removal of most mosquito-derived mutations in the vertebrate host. Thus, the chances for new adaptive WNV variants to become fixed in a population are low. Even though we found evidence for positive selection in mosquitoes, transmission of the highly fit variants were still heavily constrained by drift. In birds, new variants must maintain at least neutral fitness or risk being outcompeted by other virus genotypes. Given these circumstances, adaptive variants likely need to be generated de novo during infection of each host until the right conditions exists to allow them to become dominant. Understanding the conditions that alter selection may allow us to determine what drives the emergence of new virus strains.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

For detailed procedures, see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Ethics statement

Experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (#12–3694A) and the recommendations set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Mosquito infections and temporal saliva collection

Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. tarsalis mosquitoes ingested bloodmeals containing ~2 × 108 PFU/mL of WNV strain FtC-3699 isolated from wild-caught mosquitoes. Bloodfed individual mosquitoes were held in 50 mL conical tubes containing a scratched inner surface, a damp paper towel at the bottom, and an organdy cover (Fig. 1A). Whatman Flinders Technology Associates (FTA) filter paper (GE Healthcare) was cut into ~0.5 cm squares and soaked in 10% sucrose. The sucrose-soaked filter paper was placed on the organdy as the only food source. Mosquito saliva was expectorated onto the card during feeding, similar to an approach for arbovirus surveillance from wild mosquitoes (Hall-Mendelin et al., 2010), which could be repeatedly sampled from a single mosquito as demonstrated (Ye et al., 2015). The mosquito-exposed sucrose-soaked filter paper was collected and replaced every two days using ethanol-cleaned forceps. The method was compared to the current standard for collecting saliva by placing the proboscis of anesthetized mosquitoes into capillary tubes filled with mineral oil (Figure S1). WNV GE per saliva sample was determined by qRT-PCR. A mosquito mitochondrial DNA qPCR assay (SYBR green) was used to determine if a WNV-negative saliva sample was from a mosquito incapable of transmitting at that time or if the mosquito did not expectorate saliva on the filter paper.

Single mosquito transmission to birds

Chickens were hatched from specific pathogen free eggs (Charles River Specific Pathogen Free Avian Services) and maintained as described previously (Jerzak et al., 2007). Bloodfed mosquitoes were housed individually in 50 mL conical tubes as described above but with additional standing water at the bottom of the tube to encourage egg laying. Mosquitoes capable of transmitting WNV were determined by the presence of WNV from sucrose-soaked filter paper cards offered from 6–8 days post bloodfeeding. On 13 days post bloodfeeding, the mosquitoes capable of transmitting WNV that had laid eggs where marked by gently covering them with aerosolized fluorescent magenta (Radiant Color) from a 5 mL syringe and 18 gauge needle. The marked mosquitoes were aspirated and transported into a carton containing 8–10 unexposed mosquitoes to facilitate bloodfeeding (Culex mosquitoes prefer to bloodfeed in groups). On 14 days post bloodfeeding, the mosquitoes were allowed to feed on restrained two-days old chickens until the fluorescently marked mosquito was engorged but for no more than one hour. After bloodfeeding, saliva was immediately collected using the capillary tube method. Chickens were bled from the jugular vein on 1–4 dpi.

Sequencing and data processing

Total RNA from mosquito saliva and bird serum were randomly amplified, individually barcoded, and prepared for NGS (100 nt paired-end reads) on the HiSeq 2500 platform. The reads were aligned to the input virus genome (GenBank: KR868734), duplicates were removed, variants were called using VPhaser2 (Yang et al., 2013), and variants with significant strand bias (< 0.05) were removed. Analysis was limited to variants ≥ 0.01 frequency in the protein coding sequence (nt positions 97–10395).

Intrahost genetic diversity, demographics, and selection

Intrahost WNV genetic diversity was determined by genetic richness, distance, and complexity (i.e., Shannon entropy). Shannon entropy (S) was calculated for each intrahost population (i) using the iSNV frequency (p) at each nucleotide position (s):

| (1) |

The mean S from all sites s was used to estimate the mutant spectra complexity. FST was used to estimate genetic divergence between two virus populations as described (Fumagalli et al., 2013):

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

where pi,s, pj,s, and ps are the frequencies of the input WNV consensus nucleotide at site s from populations i, j, and combined, respectively. Only VPhaser2-called variants were used, all other sites p = 1. The number of individuals sampled, n, was set to the lowest WNV coverage depth (500 nt per genome position) to normalize for sequencing variations. The estimate of FST for the protein coding locus of m sites (10,299 nt) is:

| (4) |

Variant conservation was calculated by the proportion of variants from an ancestral population still detected in a subsequent population and was calculated separately for synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations. A low proportion of synonymous variant conservation is generally indicative of a population bottleneck and a significantly lower proportion of nonsynonymous to synonymous variant conservation suggests strong purifying selection. Intrahost selection was estimated by the ratio of nonsynonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) SNVs per site (dN/dS) using the Jukes-Cantor formula (Jukes, 1969):

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where pn equals Nd (sum of the nonsynonymous iSNV and iLV frequencies accepted by VPhaser2) divided by the number of nonsynonymous sites and ps equals Sd (sum of the synonymous iSNVs) divided by the number of synonymous sites. DnaSP (Librado and Rozas, 2009) was used to determine the number of nonsynonymous (7843.67) and synonymous (2455.33) sites from the ancestral input WNV consensus coding sequence. dN/dS was also calculated separately for the structural (nonsynonymous sites = 1793.33, synonymous sites = 579.67) and nonstructural (nonsynonymous sites = 5895, synonymous sites = 1827) protein coding regions. Statistical comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.04) for Windows.

Site-directed mutagenesis and competitive fitness

Nonsynonymous consensus changes occurring in 2 or more biological replicates are not expected to occur by chance and may be the result of positive selection. WNV mutations suspected to be influenced by positive selection were engineered into the WNVic using mutagenic primers and fragments containing overlapping sequences were amplified by rolling circle amplification, linearized, capped, and rescued in BHK-21 cells. The mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Competitive fitness of the input virus (FtC–3699), WNVic, and reconstructed WNV mutants (competitors) was determined by directly comparing their proportional abundance to a reference WNV (equally mixed in the inoculum) during co-infection in Cx. tarsalis cells (MOI 0.01) and orally infected Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (1 × 108 PFU/mL). Quantitative Sanger sequencing was used to determine the proportion of competitor to reference WNV genotypes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Individual mosquitoes can transmit distinct virus populations during each bloodmeal

The distinct virus populations are largely shaped by genetic drift

Strong selection in birds purges most nonsynonymous mutations

West Nile virus evolution characterized by cycles of diversification and selection

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Nguyen for providing mosquitoes and E. Petrilli, P. Buxton, S. Taylor, S. Schell, W. Black, K. Andersen for laboratory support and/or discussions. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for helping us to improve a previous version of this manuscript. G.D.E and his lab are supported by the NIH under grant number AI067380.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

All NGS data can be accessed from the NCBI BioProject PRJNA356740.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, G.D.E., N.D.G., and D.E.B; Methodology, N.D.G., G.D.E., D.E.B, D.R.C, J.W-L., J.R.F., and A.G.; Investigation, N.D.G., J.R.F., C.R., S.G-L., R.A.M., J.W-L., and A.G.; Writing – Original Draft, N.D.G. and G.D.E.; Writing – Reviewing & Editing, G.D.E., N.D.G., D.E.B, J.R.F, C.R., J.W-L, D.R.S., R.A.M., and S.G-L.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alto BW, Richards SL, Anderson SL, Lord CC. Survival of West Nile virus-challenged Southern house mosquitoes, Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus, in relation to environmental temperatures. Journal of vector ecology: journal of the Society for Vector Ecology. 2014;39:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2014.12078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackney DE, Beane JE, Ebel GD. RNAi targeting of West Nile virus in mosquito midguts promotes virus diversification. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000502. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackney DE, Pesko KN, Brown IK, Deardorff ER, Kawatachi J, Ebel GD. West Nile virus genetic diversity is maintained during transmission by Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackney DE, Schirtzinger EE, Harrison TD, Ebel GD, Hanley KA. Modulation of Flavivirus Population Diversity by RNA Interference. J Virol. 2015;89:4035–4039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02612-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault AC, Huang CY, Langevin SA, Kinney RM, Bowen RA, Ramey WN, Panella NA, Holmes EC, Powers AM, Miller BR. A single positively selected West Nile viral mutation confers increased virogenesis in American crows. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/ng2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciota AT, Ehrbar DJ, Van Slyke GA, Payne AF, Willsey GG, Viscio RE, Kramer LD. Quantification of intrahost bottlenecks of West Nile virus in Culex pipiens mosquitoes using an artificial mutant swarm. Infection Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff ER, Fitzpatrick KA, Jerzak GV, Shi PY, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. West Nile virus experimental evolution in vivo and the trade-off hypothesis. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002335. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel GD, Carricaburu J, Young D, Bernard KA, Kramer LD. Genetic and phenotypic variation of West Nile virus in New York, 2000–2003. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika Virus in the Americas — Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:601–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M, Vieira FG, Korneliussen TS, Linderoth T, Huerta-Sanchez E, Albrechtsen A, Nielsen R. Quantifying population genetic differentiation from next-generation sequencing data. Genetics. 2013;195:979–992. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.154740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester NL, Guerbois M, Seymour RL, Spratt H, Weaver SC. Vector-Borne Transmission Imposes a Severe Bottleneck on an RNA Virus Population. PLoS Pathog. 2012:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard YA, Klingler KA, Higgs S. West Nile virus dissemination and tissue tropisms in orally infected Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2004;4:109–122. doi: 10.1089/1530366041210729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard YA, Schneider BS, McGee CE, Wen J, Han VC, Popov V, Mason PW, Higgs S. Salivary gland morphology and virus transmission during long-term cytopathologic West Nile virus infection in Culex mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:118–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh ND, Smith DR, Brackney DE, Bosco-Lauth AM, Fauver JR, Campbell CL, Felix TA, Romo H, Duggal NK, Dietrich EA, et al. Experimental evolution of an RNA virus in wild birds: evidence for host-dependent impacts on population structure and competitive fitness. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004874. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh ND, Weger-Lucarelli J, Murrieta RA, Fauver JR, Garcia-Luna SM, Prasad AN, Black WCt, Ebel GD. Genetic Drift during Systemic Arbovirus Infection of Mosquito Vectors Leads to Decreased Relative Fitness during Host Switching. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Mendelin S, Ritchie SA, Johansen CA, Zborowski P, Cortis G, Dandridge S, Hall RA, van den Hurk AF. Exploiting mosquito sugar feeding to detect mosquito-borne pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11255–11259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002040107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EC. Error thresholds and the constraints to RNA virus evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:543–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzak G, Bernard KA, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. Genetic variation in West Nile virus from naturally infected mosquitoes and birds suggests quasispecies structure and strong purifying selection. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2175–2183. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81015-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzak GV, Bernard K, Kramer LD, Shi PY, Ebel GD. The West Nile virus mutant spectrum is host-dependant and a determinant of mortality in mice. Virology. 2007;360:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerzak GV, Brown I, Shi PY, Kramer LD, Ebel GD. Genetic diversity and purifying selection in West Nile virus populations are maintained during host switching. Virology. 2008;374:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. Evolution of protein molecules. III. New York: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AM, Meola MA, Moudy RM, Kramer LD. Temperature, viral genetics, and the transmission of West Nile virus by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 2008:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer LD, Styer LM, Ebel GD. A global perspective on the epidemiology of West Nile virus. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:61–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Rowley WA, Platt KB. Longevity and spontaneous flight activity of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) infected with western equine encephalomyelitis virus. Journal of medical entomology. 2000;37:187–193. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequime S, Fontaine A, Ar Gouilh M, Moltini-Conclois I, Lambrechts L. Genetic Drift, Purifying Selection and Vector Genotype Shape Dengue Virus Intra-host Genetic Diversity in Mosquitoes. Plos Genetics. 2016;12:e1006111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood F, Reisen WK, Chiles RE, Fang Y. Western equine encephalomyelitis virus infection affects the life table characteristics of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) Journal of medical entomology. 2004;41:982–986. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudy RM, Meola MA, Morin LL, Ebel GD, Kramer LD. A newly emergent genotype of West Nile virus is transmitted earlier and more efficiently by Culex mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:365–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisen WK, Fang Y, Martinez VM. Effects of temperature on the transmission of west nile virus by Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) Journal of medical entomology. 2006;43:309–317. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)043[0309:EOTOTT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions OM, Wilm A, Kamaraj US, Choy MM, Chow A, Chong Y, Ong XM, Nagarajan N, Cook AR, Ooi EE. Analysis of Dengue Virus Genetic Diversity during Human and Mosquito Infection Reveals Genetic Constraints. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim S, Aw PP, Wilm A, Teoh G, Hue KD, Nguyen NM, Nagarajan N, Simmons CP, Hibberd ML. Tracking Dengue Virus Intra-host Genetic Diversity during Human-to-Mosquito Transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleford KA, Coffey LL, Lay S, Borderia AV, Duong V, Isakov O, Rozen-Gagnon K, Arias-Goeta C, Blanc H, Beaucourt S, et al. Emergence and Transmission of Arbovirus Evolutionary Intermediates with Epidemic Potential. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:706–716. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Suzuki K. Japanese encephalitis virus in mosquito salivary glands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:122–135. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, Mcgee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1895–1906. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelk CH, Holmes EC. Reduced positive selection in vector-borne RNA viruses. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2002;19:2333–2336. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Charlebois P, Macalalad A, Henn MR, Zody MC. V-Phaser 2: variant inference for viral populations. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:674. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye YH, Carrasco AM, Frentiu FD, Chenoweth SF, Beebe NW, van den Hurk AF, Simmons CP, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. Wolbachia Reduces the Transmission Potential of Dengue-Infected Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G, Zhang B, Lim PY, Yuan ZM, Bernard KA, Shi PY. Exclusion of West Nile Virus Superinfection through RNA Replication. J Virol. 2009;83:11765–11776. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01205-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.