Abstract

Adipose tissues have a central role in energy homeostasis, as they secrete adipokines and regulate energy storage and dissipation. Novel adipokines from white, brown and beige adipocytes have been identified in 2016. Identifying the specific receptors for each adipokine is pivotal for developing greater insights into the fat-derived signalling pathways that regulate energy homeostasis.

White adipose tissue (WAT), which accounts for anywhere from 5% to 50% of human body weight, is a major source of endocrine signalling. As a testament to the importance of adipose tissue as a crucial endocrine organ, leptin therapy for individuals with generalized lipodystrophy who frequently develop severe hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus has been approved by the FDA since 2014 (REF. 1).

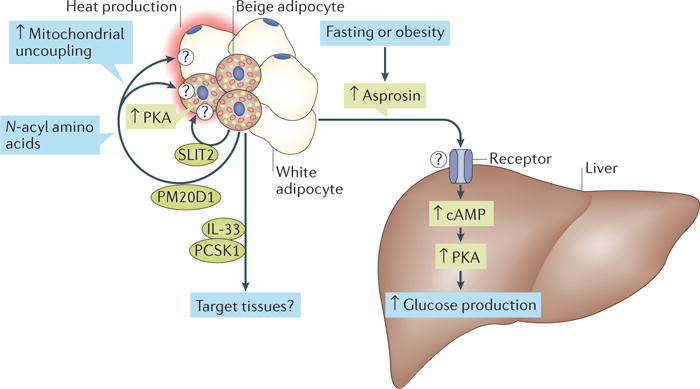

Although generalized lipodystrophy is frequently associated with insulin resistance, patients with neonatal progeroid syndrome (NPS; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) #264090) develop a rare form of partial lipodystrophy in which they remain insulin sensitive and euglycaemic. In 2016, Chopra and colleagues identified mutations in the gene that encodes profibrillin (FBN1) in patients with NPS; the mutations were found to disrupt the expression of asprosin, the C-terminal cleavage product of profibrillin2. Asprosin, which is a 140-amino-acid secreted polypeptide, is abundantly expressed in mature white adipocytes and is thus considered a new adipokine. The authors found that levels of asprosin were raised under fasting conditions in healthy humans and rodents. Remarkably, a single injection of recombinant asprosin to wild-type mice induced a significant increase in plasma levels of glucose and insulin within 30 min. Mechanistically, asprosin acts directly on the liver to stimulate hepatic glucose production by increasing intracellular cAMP levels, subsequently activating the protein kinase A (PKA) signalling pathway. Of note, plasma levels of asprosin (in the range of 5–10 nM) in humans with obesity and mouse models of obesity are higher than those in non-obese controls in concordance with insulin levels, which suggests that asprosin levels are associated with insulin resistance. Blocking asprosin action, via a neutralizing antibody against asprosin or genetic deletion of Fbn1, reduced plasma levels of insulin and hepatic glucose production in vivo. These data provide compelling evidence that asprosin is a fasting-induced adipokine that controls hepatic glucose production and insulin sensitivity. The study also suggests that there is an as yet uncharacterized receptor (or receptors) in hepatocytes through which asprosin acts to trigger cAMP–PKA signalling (FIG. 1). Blocking asprosin and its downstream pathways might be beneficial for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 1. The regulation of systemic glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity through adipokines.

Newly identified secretory molecules from white, brown and beige adipocytes control thermogenesis, hepatic glucose production and/or insulin sensitivity. PCSK1, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1; PKA, protein kinase A; PM20D1, peptidase M20 domain-containing protein 1; SLIT2, Slit homologue 2 protein.

In addition to WAT, mammals have brown adipose tissue (BAT), which dissipates energy in the form of heat and staves off hypothermia and obesity. Owing to the much smaller mass of BAT than WAT in the human body (~60 g of BAT in the average adult3), its contribution as an endocrine organ to whole-body home-ostasis seems to be marginal. However, recent studies have reported on secretory molecules from BAT, so called ‘batokines’, which include fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), neuregulin 4 (NRG4), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and bone morphogenetic protein 8B (BMP8B). These studies indicate a physiological role of BAT as an endocrine organ4. Notably, an ‘inducible form’ of thermogenic adipocytes, known as beige adipocytes, exists in adult humans5. Beige adipocyte differentiation can be induced by chronic cold exposure, exercise, cancer cachexia and bariatric surgery6. Given the recent animal studies showing its biological importance in the regulation of whole-body energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis, it is probable that batokines mediate, at least in part, the metabolic improvements achieved by increased beige fat mass6.

In fact, studies published in 2016 support the above-described hypothesis. In a study by Corvera and colleagues, the authors obtained human beige adipocytes derived from the capillaries of subcutaneous WAT and then implanted the adipocytes into mice with diet-induced obesity7. The mice implanted with human beige adipocytes had lower levels of fasting blood glucose, increased glucose tolerance and reduced hepatic steatosis 7 weeks after the implantation compared with control mice implanted with matrigel (vehicle). Improved glucose tolerance following implantation of beige adipocytes was associated with an increased glucose turnover rate and adiponectin secretion from the transplanted human beige adipocytes. Notably, the authors identified several secretory factors, such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (encoded by PCSK1), its substrate proenkephalin (encoded by PENK) and IL-33 (encoded by IL33), which were abundantly expressed in the human beige adipocytes. This study reinforces the notion that increased beige fat mass affects whole-body glucose homeostasis; however, determining the causal link between these secretory molecules and the metabolic improvement that is achieved by implanting beige adipocytes requires further investigation (FIG. 1).

Two further studies published in 2016 have identified previously unknown batokines, peptidase M20 domain-containing protein 1 (PM20D1) (REF. 8) and Slit homologue 2 protein (SLIT2) (REF. 9), which regulate whole-body energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis (FIG. 1). Long and co-workers used global transcriptional profiling and identified PM20D1 as a secretory enzyme that was highly enriched in mitochondrial brown fat uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1)-positive cells (that is, brown and beige adipocytes)8. When overexpressed in mice, PM20D1 catalyses the synthesis of N-acyl amino acids from free fatty acids, thereby increasing whole-body energy expenditure, which leads to reduced fat mass and body weight. The authors further showed that N-acyl amino acids increase cellular respiration and reduce body weight by functioning as a mitochondrial uncoupler. As the thermogenic effect was found in UCP1-positive and UCP1-negative cells, N-acyl amino acids probably act not only on brown and beige adipocytes but also on neighbouring cells (FIG. 1). Notably, the authors identified several mitochondrial proteins, including ANT1 and ANT2, that bind directly to N-acyl amino acids. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms by which N-acyl amino acids are taken up into the target cells and stimulate mitochondrial uncoupling.

Svensson et al. used quantitative proteomics to search for molecules that are secreted by beige adipocytes9. The authors found that the C-terminal fragment of SLIT2 (SLIT2-C) is cleaved from the full-length SLIT2 protein; SLIT2-C activates thermogenesis in BAT and beige adipose tissue. It does so by activating the PKA signalling pathway, which is a well-known downstream pathway, in response to cold exposure and β-adrenergic receptor activation. Although these molecules are enriched in brown and beige adipocytes, they are also expressed in non-adipose tissues. Thus, further analyses using tissue-specific knockout mouse models are needed to determine the relative contributions of the secretory factors derived from BAT and beige adipose tissue versus alternative tissues in the regulation of whole-body metabolism.

As we learn more about the various roles of beige adipocytes in thermogenesis, glucose metabolism and lipid homeostasis, it might be conceivable that multiple types of beige adipocytes with distinct functional roles exist within adipose tissue. In this regard, a paper by Graff and colleagues used a variety of Creinducible mouse lines to critically investigate the developmental origins of beige adipocytes in response to cold exposure10. The authors found that perivascular mouse cells expressing smooth muscle actin gave rise to 60–68% of UCP1-positive beige adipocytes, whereas existing mature white adipocytes did not give rise to beige adipocytes. These data might indicate that additional lineages of beige adipocytes exist within a WAT depot.

In summary, the new studies published in 2016 made important advances in the field of adipose biology with the identification of new signalling entities from adipocytes that control systemic energy balance. Clearly, the identification of their specific receptors will be an important future theme in the field; this will enable us to determine their target tissues and/or cells and the underlying mechanisms of their actions.

Key advances.

A new adipokine, asprosin, promotes hepatic glucose production. Inhibition of pathologically raised levels of asprosin protects against obesity-linked hyperinsulinaemia2

Transplantation of human beige adipocytes improves systemic glucose homeostasis in mice with diet-induced obesity7

New batokines, PM20D1 and SLIT2, contribute to the regulation of whole-body thermogenesis and systemic glucose homeostasis8,9

Footnotes

Competing interests statement.

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sinha G. Leptin therapy gains FDA approval. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:300–302. doi: 10.1038/nbt0414-300b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romere C, et al. Asprosin, a fasting-induced glucogenic protein hormone. Cell. 2016;165:566–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virtanen KA, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1518–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villarroya F, Cereijo R, Villarroya J, Giralt M. Brown adipose tissue as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;13:26–35. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinoda K, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of clonally derived adult human brown adipocytes. Nat Med. 2015;21:389–394. doi: 10.1038/nm.3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kajimura S, Spiegelman BM, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: physiological roles beyond heat generation. Cell Metab. 2015;22:546–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Min SY, et al. Human ‘brite/beige’ adipocytes develop from capillary networks, and their implantation improves metabolic homeostasis in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22:312–318. doi: 10.1038/nm.4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long JZ, et al. The secreted enzyme PM20D1 regulates lipidated amino acid uncouplers of mitochondria. Cell. 2016;166:424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svensson KJ, et al. A secreted Slit2 fragment regulates adipose tissue thermogenesis and metabolic function. Cell Metab. 2016;23:454–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry DC, Jiang Y, Graff JM. Mouse strains to study cold-inducible beige progenitors and beige adipocyte formation and function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10184. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]