Graphical abstract

Keywords: Industrial lignin, Wet ball milling, Ionic liquid pretreatment, Polydispersity, Functional groups

Highlights

-

•

Two pretreatment methods were investigated to improve the quality of industrial lignin.

-

•

ILP significantly reduced the average molecular weight and polydispersity of lignin.

-

•

The methoxy group of lignin showed obviously decrease after ionic liquid pretreatment.

-

•

ILP with [Emim][OAc] is an effective way to enhance the quality of industrial lignin.

Abstract

As the most abundant aromatic compounds, lignin is still underutilized due to its relatively low quality. In order to improve its quality, two pretreatment technologies, wet ball milling (WBM) and ionic liquid pretreatment (ILP) were tested on the industrial lignin and evaluated on the average molecular weight and polydispersity, surface morphology, and functional groups changes. The results showed that the lignin pretreated by the WBM with phosphoric acid presented dramatic decrease of polydipersity (23%) and increase of phenolic hydroxyl content (9%). While, the ILP treated samples exhibited the significant reduction of the average molecular weight and polydispersity. The decrease on the particle size and the emergence of the porous structure were found when treated with [Emim][OAc]. In addition, the remarkable reduction of the methoxy groups were observed to be 50% and 45% after treated with [Bmim]Cl and [Emim][OAc], respectively.

1. Introduction

As one of the major components in the plant cell wall, lignin is the most abundant natural aromatic compounds on earth [32]. Presently, there are two main lignin resources from the existing industry: papermaking industry and bio-refining industry [18]. The papermaking industry alone produces 50 million tons of lignin annually which is mostly used as energy source by combustion and not more than 2% for producing phenolic resins, polyurethane foams, bio-dispersants and epoxy resins etc. [11]. To make good use of lignin can not only alleviate pollution to the environment caused by papermaking industry, but also improve market competitiveness of bio-refining industry, and thus relieve the energy crisis related to the shortage of petrochemical resources [13]. Two main reasons have been identified to restrict the high valorization of the industrial lignin: high dispersity of molecular weight and relatively low reactivity [16]. In order to improve the reactivity of lignin, many methods have been proposed, including methylation, demethylation, acetylation, etc. Wu and Zhan’s study (2001) showed that the content of methoxyl groups in wheat straw soda lignin, decreased from 10.39% to 6.09% after demethylation, while the contents of the phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups increased from 2.98% and 4.58% to 5.51% and 7.10%, respectively [33]. investigated the methylation of pine Kraft lignin which revealed that about 0.36 mole of hydroxymethyl group per C9 unit was introduced. The adhesive made from the hydroxymethylated Kraft lignin and phenol-formaldehyde resin (50%:50%, w/w) could reach bond strength of 65 psi in a lab test. With up to the 30% substitution of the phenolated lignin to phenol in the synthesis of lignin-based phenol-formaldehyde resin, the obtained resin had the similar mechanical and physical properties to the commercial phenol-formaldehyde resin [6]. However, these methods use toxic organic reagent and the operation process is complicated. Therefore, it is necessary to find green and feasible method to improve the lignin quality. Pretreatment is one of the most important operation unit in biorefinery process [12]. Many physical and chemical pretreatment methods have been successfully employed to overcome the recalcitrance of biomass and improve the yields of monomeric sugars, including ball milling, dilute acid, steam expansion, hot water, ionic liquids and organic solvent [5]. Among these biomass pretreatment techniques, wet ball milling (WBM) seems to be one of the promising pretreatment process in terms of polydispersity reduction and reactivity improvement. Compared to the traditional acid hydrolysis technologies, which causes equipment corrosion and further degradation of biomass to form inhibitor, mild acid hydrolysis coupling ball milling at room temperature could provide a simpler and less harsh treatment [34]. Yamashita et al. [31] revealed that the combination of ball milling and phosphoric acid swelling is an effective pretreatment method for the production of ethanol from paper sludge. In addition, the investigation of [17] indicating that the treatment effect of wet ball milling is better than that of dry milling.

Recently, ionic liquids (ILs) have become very popular solvents for the dissolution of biomass [9]. Ionic liquids pretreatment (ILP) can reduce the cellulose crystallinity by partially removing hemicellulose and lignin, and thus enhance the digestibility of biomass [24]. ILP are less energy demanding, more environmentally friendly and easier to handle [25]. Lee et al. [15] found that 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc]) can selectively extract lignin from wood with less crystalline cellulose remaining. Pu et al. [23] observed that the properties of the anion are extremely important in the solubility of lignin in ionic liquids. The recyclability of ionic liquids also has been demonstrated by some studies [19].

To our knowledge, no investigation has been reported in implementing the existing pretreatment process in biorefinery on lignin which might be helpful to improve the lignin quality. WBM and ILP were employed to treat industrial lignin in the present study. The changes of molecular weight, polydispersity, surface morphology and functional groups were also investigated.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Material

Industrial lignin was purchased from Changzhou Peaks Chemical Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China). Its main composition was 93.35% lignin, 2.31% carbohydrates and 2.11% ash. N-methylimidazole, 1-chlorobutane and 1-bromoethane were purchased from Shanghai Jingchun Chemical Reagent Company; phosphoric acid, potassium acetate, toluene, dichloromethane, acetic anhydride, pyridine, chloroform and diethyl ether were purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagent Company, All reagents were used as supplied without further purification.

2.2. Wet ball milling pretreatment (WBM)

The ball-milling process was performed in a WL-IA planetary ball mill (Rishengjiuyuan Co., Ltd., Tianjing, China) equipped with four zirconia milling jar (500 ml for each one). Each jar was loaded with 30 g industrial lignin, 80 ml phosphoric acid (4%, w/v) and 30 zirconia balls (φ = 10 mm) and milled at 400 rpm for 30 min. The sample prepared by WBM with water (WBM-H2O) was used as control. The mixture after WBM was filtered and washed with five times volume of water until the filtrate were approaching neutral. The residue was dried in vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight, then sealed for the following analysis. Duplicates were run for WBM with phosphoric acid (WBM-H3PO4) or WBM-H2O. The solid recovery rate (Rs) was calculated as following:

| (1) |

m0: Mass of raw feedstock, dry weight, g;

m1: Mass of pretreated samples, dry weight, g.

2.3. Ionic liquid pretreatment (ILP)

1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium chlorine ([Bmim]Cl) and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc]) were mixed with industrial lignin at a ratio of 20:1, respectively. After 120 °C for 30 min, deionized water was added at a ratio of 5:1 to recover the lignin by vacuum filtration. The recovered solid was washed repeatedly with deionized water until the filtrate appeared colorless before it was dried in vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight. The dried sample was used for the following analysis. Each treatment was carried out twice. The solid recovery rate (Rs) was calculated based on Eq. (1).

2.4. Analysis methods

2.4.1. Dry matter content

Dry matter content was determined by the moisture analyzer, Mettler Toledo HR83. Duplicate experiments were run for each sample.

2.4.2. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis

GPC was used to determine the weight average molecular weight (Mw) and number average molecular weight (Mn) of industrial lignin before and after pretreatment. The GPC analysis was done as described by [8]. The sample (50 mg) was dissolved in 2 ml mixture of acetic anhydride/pyridine (1:1, v/v) and shaken at room temperature, 150 rpm. After 24 h, the reaction was terminated by adding anhydrous ethanol (25 ml), and shaken at room temperature, 150 rpm for another 30 min, the solvent was then removed by vacuum rotary evaporation. The acetylated lignin was dissolved in chloroform (2 ml) and precipitated with diethyl ether (100 ml), followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm, for 10 min. The precipitate was washed with diethyl ether for three times and dried under vacuum at 40 °C overnight. The dried acetylated lignin was dissolved in THF (20 mg/ml) and filtered through a 0.45 μm organic membrane filter. The GPC analysis was carried out by HPLC (Agilent Technologies, 1260 Infinity) using a Styragel columns (PLgel mixed-C) at 25 °C and THF as eluent at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. A refractive index detector (RID) was used. Polystyrene standards were used as the calibration for the molecular weight of lignin [30].

2.4.3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

SEM was used to characterize the changes on morphology before and after different pretreatments. The sample for SEM was prepared by spray-gold processing to make it conductive, avoiding degradation and buildup of charge on the specimen [24]. A Hitachi S-4800 scanning microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan) operated at 15 kV was used to observe the samples.

2.4.4. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The investigation of lignin by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was carried out using a JASCO FT/IR-660 plus spectroscopy. Each sample was prepared by KBr disk method [3]. The region between 4000 and 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 80 scans were recorded.

2.4.5. Ultraviolet/visible (UV/vis) lignin analysis for ionization spectra

The lignin samples were characterized by differential UV/vis spectroscopy. The method is based on the difference in absorption between lignin in alkaline and neutral solution [1]. In alkaline solution, phenolic hydroxyl groups are ionized and the absorption changes towards longer wavelengths and higher intensities. By subtracting the spectrum derived from the neutral solution from that of the alkaline solution, an ionization difference spectrum is obtained. The UV/vis data was obtained by using an UV765 spectrophotometer (Shanghai Precision & Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd). The absorption spectra were recorded from 200 to 500 nm with a bandwidth of 1 nm and a fast scan speed mode was used. The spectra were determined by adding 5 ml of lignin solution (0.06 g/l in 1:1 v/v 2-mercaptoethanol and water) to 1 ml of either 0.6 M NaOH (alkali spectra) or phosphate buffer at pH 6.5 (neutral spectra) [7].

2.4.6. Analysis of lignin functional groups

The content of the phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of the sample was determined by aqueous phase potentiometric titration [35]. The procedure was as follows: 0.03 g lignin sample was dissolved into 5 ml of potassium hydroxide solution (1.0 M, pH 14), and 0.05 g p-hydroxybenzonic acid was added as the internal standard. After the mixture was treated by ultrasound for 30 min, the content of phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups were titrated with 0.25 M hydrochloric acid by a ZDJ-4A potentiometric titrator (INESA.CC, Shanghai, China). The mixture without addition of lignin sample was used as the control. The content of the methoxy group of the different lignin sample was determined by Zeisel’s method. The experiment was conducted by a 7460 methoxy group determination instrument (Shanghai Ci Yue Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., China).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Recovery of solid residue after pretreatment

After different pretreatments on the industrial lignin, the solid recovery was calculated based on Eq. (1) and presented in Fig. 1. It is obvious that the solid recovery were maintained at a higher level for all the pretreatments. However, there was a dramatic difference between the WBM (higher than 90%) and ILP (lower than 90%). After WBM-H2O or WBM-H3PO4 treatment, the solid recovery was 95.50% and 92.62%, respectively. The weight loss may be related to the soluble fraction in the sample, including part of soluble lignin and some soluble impurities. Compared to WBM, lower solid recovery after ILP was obtained, which were 84.25% (treated by [Bmim]Cl) and 81.30% (treated by [Emim][OAc]), respectively. In addition to the above reasons resulting in the weight loss, degradation of a small amount of lignin into water-soluble substances during the ILP might be occurred [10], which caused the relatively low solid recovery.

Fig. 1.

Solid recovery of industrial lignin after different pretreatments.

3.2. Molecular weight

The weight average molecular weight (Mw), number average molecular weight (Mn) and polydispersity changes on the industrial lignin before and after pretreatment are shown in Table 1. When using water as a milling medium, lignin molecular weight and polydispersity were increased. As the industrial lignin possesses a strong hydrophobicity, which causes condensation among different lignin molecular weight during the WBM-H2O, especially among large molecule, thereby increases the average molecular weight [22]. While, unlike the large molecule, the condensation probability of the small one was much lower and the non-uniformity of the latter may be the reason why the polydispersity of the WBM-H2O treated lignin increased. When treated by WBM-H3PO4, the polydispersity was lower than the original lignin. Xu et al. [30] revealed that ball milling with acid can cause some lignin depolymerization by cleaving some inter-unit bonds in lignin, such as β-aryl ether linkages. Moreover, the negative charge of lignin surface were neutralized by the H+ in an acid medium, which result in the condensation of the lignin molecule [26]. Due to the above reasons, WBM-H3PO4 was found to effectively reduce the polydispersity of the industrial lignin in the present study. Dissimilar to the process of WBM, the molecular weight and polydispersity have been reduced simultaneously after the two different ionic liquids treatment employed in this investigation. The reasons might exist in: (1) the two ionic liquids have good solubility to the lignin [32], thus form a homogeneous processing environment and improve the effect of pretreatment; (2) ILP may cause the breakage of secondary and weak ether linkages of lignin macromolecule, thereby reduce the molecular weight and polydispersity of lignin. Fort et al. [9] have revealed that [Bmim]Cl can partially dissolve wood, which may owing to the strong hydrogen-bonding basicity of the chloride anion. The same research group subsequently demonstrated that [Emim][OAc] can completely dissolve wood and also show high potential to solubilize lignin [28]. The characteristic differences of the two ionic liquids are mainly associated with the anions [23]. It has been proved that the anion of ionic liquids underwent nucleophilic attack or catalyzed the β-O-4 lignin linkages, thus reducing the average molecular weight and the polydispersity [14]. The results of the present study showed the similar trend.

Table 1.

Weight average molecular weight (Mw), number average molecular weight (Mn) and polydipersion changes of lignin samples, before and after pretreatment.

| Lignin sample | Mw(g/mol) | Mn(g/mol) | Mw/Mn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial lignin | 2726 | 1080 | 2.52 |

| WBM-H2O | 3527 | 1143 | 3.09 |

| WBM-H3PO4 | 2819 | 1453 | 1.94 |

| ILP-[Bmim]Cl | 2276 | 660.5 | 2.41 |

| ILP-[Emim][OAc] | 1465 | 631 | 2.32 |

3.3. Microstructural changes on lignin before and after pretreatment

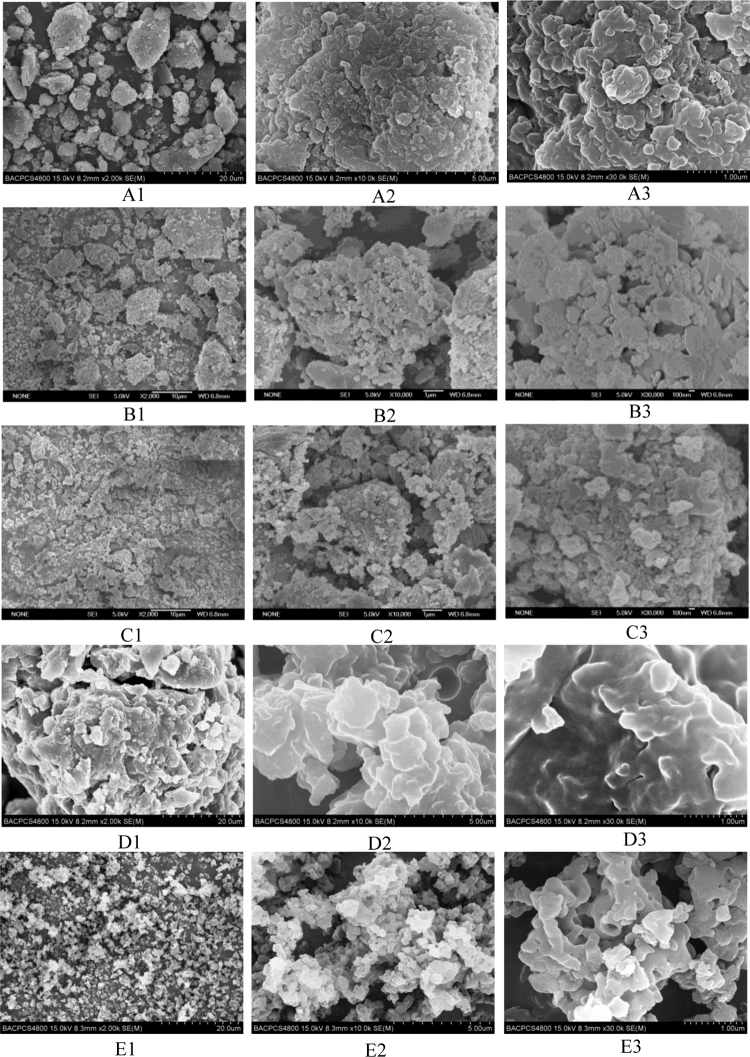

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of lignin samples before and after pretreatment are given in Fig. 2(A1–E3). As can be seen from them, the particle size and surface morphology of the lignin display significant changes after different treatments. In WBM process, the particle size of the WBM-H2O treated samples showed some increase (Fig. 2B1). While the particle size of the WBM-H3PO4 treated sample showed some decrease (Fig. 2C1). Zhou et al. [34] demonstrated that there was a synergistic effect of mechanical milling and chemical modification (such as mild acid) which reduced the particle size and improved the surface area of rice hull. However, the surface of the samples was observed not obvious change after both WBM treatments (Fig. 2B3 and C3). Compared to the WBM, particle size of the ILP lignin samples decreases obviously (Fig. 2D1 and E1), especially the sample treated with [Emim] [OAc] which showed a dramatic decrease on the particle size and better uniformity, and grain surface appeared some channel structure (Fig. 2E3). The channel structure has been identified to increase the specific surface area, thus increase the conversion efficiency [4].

Fig. 2.

SEM images of lignin samples before and after pretreatment.

*A1–A3 Industrial lignin; B1–B3 WBM-H2O treated sample; C1–C3 WBM-H3PO4 treated sample; D1–D3 ILP-[Bmim]Cl treated sample; E1–E3 ILP-[Emim][OAc] treated sample. Subscript numbers 1–3 represent the multiple of 2000 times, 10000 times and 30000 times, respectively.

3.4. Infrared spectroscopy

To obtain (characterize) the functional group changes, the FTIR spectra of the treated/untreated industrial samples have been measured. As depicted in Fig. 3, all lignin samples showed the band at 3440 cm−1, which represents the stretching of the hydroxyl groups in phenolic and aliphatic structures. The bands at 2930 and 2844 cm−1 relate to C—H stretching in aromatic methoxyl, methylene and methyl groups, which displayed little difference among all the samples. The absorption band at 1705 cm−1 represents the stretching of C O including carboxyls, carbonyls and quinones [20]. Compared to the untreated industrial lignin, the WBM treated lignin showed no obvious change on the absorption. On the contrary, the ILP treated lignin samples displayed a significant reduce of absorption at 1705 cm−1, which may be related to the broken or isomerized of ketone carbonyl group or ester bonds of the sample during the treatment [2]. The most obvious characteristic absorption of lignin corresponding to the aromatic rings has been identified at 1600, 1515 and 1425 cm−1 [30]. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the vibration of the aromatic rings showed minor change between the untreated and the pretreated sample, which demonstrated that the pretreatment did not cause significant degradation of the aromatic rings in lignin [14], and it is beneficial to further use to convert to aromatic chemicals. The bands at 1270, 1032 cm−1 are corresponding to guaiacyl units of lignin, while the bands at 1220, 1120 cm−1 attribute to syringyl units of lignin [3]. Compared to the other samples, the ILP lignin showed enhancement of absorption at 1220 cm−1, indicating that the content of syringyl units were higher than the others. This will benefit for the conversion of syringyl products from lignin.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR spectra of lignin samples, before and after different pretreatments.

3.5. UV/vis lignin analysis for ionization spectra

The UV/vis was applied to study the phenolic hydroxyl content and structure changes on the lignin before/after pretreatment and the results are shown in Fig. 4. Under alkaline condition, phenolic hydroxyl groups in the lignin was ionized into phenolate ion, consequently the characteristic absorption move to longer wavelength and the intensity of absorption increased as well [7]. Compared to the untreated industrial lignin, the wavelength of WBM treated lignin at 250, 300 and 350 nm were much higher as can be seen from Fig. 4, indicating that the content of phenolic hydroxyl groups increased after the treatment. It may be related to the rupture of phenol ether bond, especially the β-O-4 ether bond, of lignin in the WBM process [27]. Evidently, both the IL treated samples exhibited the three basic UV absorption peaks as other samples. However, the shift of the maximum wavelength from 350 to 345 nm was observed and the absorption peaks became sharper, which indicating that a relatively higher content of syringyl units in the samples [30]. These results were also consistent with that of the FTIR spectra.

Fig. 4.

Differential ionization UV/vis spectra of lignin samples.

3.6. Changes in concentrations of functional groups

3.6.1. Phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups content

The phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl content of lignin was determined by the aqueous titration method. As can be seen from Fig. 5, the phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl group content of the lignin samples showed dramatic change, before and after pretreatment. The phenolic hydroxyl group content of the lignin samples increased after WBM treatment, while the content of carboxyl remained little change. The phenolic hydroxyl content of the WBM-H3PO4 treated lignin samples showed the significant increment (about 9%), compared to the untreated and WBM-H2O treated lignin (about 2%). Three reasons might be responsible for this increment: (1) phosphoric acid can penetrate into the internal structure of lignin macromolecules, which play a swelling effect [31] which made more phenolic hydroxyl group exposed; (2) partially breakage of the phenol ether bond within the molecule of lignin were happened [27]; (3) the synergistic effect of mechanical milling and chemical modification may play an important role. However, the ionic liquid treated lignin samples presented lower content of phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl group. The [Bmim]Cl treated lignin had the greatest reduction (about 26% for phenolic hydroxyl and 17% for carboxyl), while the change made by [Emim][OAc] was not significant (about 4% for phenolic hydroxyl and 11% for carboxyl). Although the decrease of phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups may lower the reactivity of lignin, the content of these two groups still remained at high level after the ILP process, especially the [Emim][OAc] treated sample.

Fig. 5.

Phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups content of lignin samples.

3.6.2. Methoxy group content

Since the majority of phenolic hydroxyl groups were captured by methyl in the form of methoxy group, the demethylation may release more phenolic hydroxyl group and increase the lignin reactivity. The investigation made by [29] found that demethylation can improve the reactivity of wheat straw soda lignin and a substitution of 60% demethylated lignin for phenol in the synthesis of phenolic formaldehyde resin can meet the national standard. The determination of methoxy group content in the lignin sample before/after treatment can reveal the extent of demethylation. As shown in Fig. 6, compared to the untreated industrial lignin, the methoxy group content of WBM treated lignin did not show obvious change, indicating that WBM caused little damage to the methoxy ether bond. The content of methoxyl group decreased obviously after ILP with [Bmim]Cl and [Emim][OAc]. The reduction was found to be 50% and 45%, respectively which may be due to the transformation of the aromatic rings in quinonoid structures [21].

Fig. 6.

Methoxy group content of lignin samples.

4. Conclusion

Compared to the WBM, ILP was confirmed to be effective in improving the quality of the industrial lignin by reducing the average molecular weight and polydispersity. When lignin was treated by [Emim][OAc], a drastic reduction on the particle size and emergence of the porous structure were found and the methoxy group was reduced by 45%. In addition, ILP with [Emim][OAc] also showed the capability to preserve the phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. This might increase its reaction activity in the subsequent conversion process which will be tested in the future work.

Acknowledgments

The work was financially supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program: 2012AA022301), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21276259) and the 100 Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

Available online 5 January 2015

Reference

- 1.Aulin-Erdtman G. Spectrographic contributions to lignin chemistry V. Phenolic groups in spruce lignin. Svensk Papperstidn. 1954;57:745–760. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder J.B., Gray M.J., White J.F., Zhang Z.C., Holladay J.E. Reactions of lignin model compounds in ionic liquids. Biomass Bioenerg. 2009;33:1122–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeriu C.G., Bravo D., Gosselink R.J.A., van Dam J.E.G. Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy. Ind. Crop Prod. 2004;20:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridgeman T.G., Darvell L.I., Jones J.M., Williams P.T., Fahmi R., Bridgwater A.V., Barraclough T., Shield I., Yates N., Thain S.C., Donnison I.S. Influence of particle size on the analytical and chemical properties of two energy crops. Fuel. 2007;86:60–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodeur G., Yau E., Badal K., Collier J., Ramachandran K.B., Ramakrishnan S. Chemical and physicochemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: a review. Enzyme Res. 2011:1–17. doi: 10.4061/2011/787532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cetin N.S., Özmen N. Use of organosolv lignin in phenol–formaldehyde resins for particleboard production: I. Organosolv lignin modified resins. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2002;22:477–480. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyer T.J., Ragauskas A.J. Deconvoluting chromophore formation and removal during kraft pulping: influence of metal cations. Appita J. 2006;59:452–458. [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Hage R., Brosse N., Chrusciel L., Sanchez C., Sannigrahi P., Ragauskas A. Characterization of milled wood lignin and ethanol organosolv lignin from Miscanthus. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009;94:1632–1638. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fort D.A., Remsing R.C., Swatloski R.P., Moyna P., Moyna G., Rogers R.D. Can ionic liquids dissolve wood? Processing and analysis of lignocellulosic materials with 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride. Green Chem. 2007;9:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.George A., Tran K., Morgan T.J., Benke P.I., Berrueco C., Lorente E., Wu B.C., Keasling J.D., Simmons B.A., Holmes B.M. The effect of ionic liquid cation and anion combinations on the macromolecular structure of lignins. Green Chem. 2011;13:3375–3385. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosselink R.J.A., de Jong E., Guran B., Abächerli A. Co-ordination network for lignin-standardisation, production and applications adapted to market requirements (EUROLIGNIN) Ind. Crop Prod. 2004;20:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendriks A.T., Zeeman G. Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009;100:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holladay, J., Bozell, J., White, J., Johnson, D. Top value-added chemicals from biomass. DOE Report PNNL-16983, 2007 (website: http://chembioprocess.pnl.gov/staff/staff_info.asp).

- 14.Hossain M.M., Aldous L. Ionic liquids for lignin processing: dissolution, isolation, and conversion. Aust. J. Chem. 2012;65:1465–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S.H., Doherty T.V., Linhardt R.J., Dordick J.S. Ionic liquid-mediated selective extraction of lignin from wood leading to enhanced enzymatic cellulose hydrolysis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009;102:1368–1376. doi: 10.1002/bit.22179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu L., Pan H., Zhou Y., Zhang M. Methods to improve lignin’s reactivity as a phenol substitute and as replacement for other phenolic compounds: a brief review. BioResources. 2011;6:3515–3525. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Z.X., Huang H., Zhang H.M., Zhang L., Yan S., Chen J.W. Ball milling pretreatment of corn stover for enhancing the efficiency of enzymatic hydrolysis. Appl. Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;162:1872–1880. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-8965-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lora J.H., Glasser W.G. Recent industrial applications of lignin: a sustainable alternative to nonrenewable materials. J. Polym. Environ. 2002;10:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozano P., Bernal B., Recio I., Belleville M.-P. A cyclic process for full enzymatic saccharification of pretreated cellulose with full recovery and reuse of the ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride. Green Chem. 2012;14:2631–2637. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancera A., Fierro V., Pizzi A., Dumarçay S., Gérardin P., Velásquez J., Quintana G., Celzard A. Physicochemical characterisation of sugar cane bagasse lignin oxidized by hydrogen peroxide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010;95:470–476. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nada A., Yousef M.A., Shaffei K.A., Salah A.M. Infrared spectroscopy of some treated lignins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998;62:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norgren M., Edlund H., Wågberg L. Aggregation of lignin derivatives under alkaline conditions. Kinetics and aggregate structure. Langmuir. 2002;18:2859–2865. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pu Y., Jiang N., Ragauskas A.J. Ionic liquid as a green solvent for lignin. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2007;27:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu Z., Aita G.M., Walker M.S. Effect of ionic liquid pretreatment on the chemical composition, structure and enzymatic hydrolysis of energy cane bagasse. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;117:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers R.D., Seddon K.R. Ionic liquids–solvents of the future? Science. 2003;302:792–793. doi: 10.1126/science.1090313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudatin S., Sen Y.L., Woerner, DL Association of Kraft lignin in aqueous solution. Lignin Prop. Mater. 1989:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuel R., Pu Y.Q., Raman B., Ragauskas A.J. Structural characterization and comparison of switchgrass ball-milled lignin before and after dilute acid pretreatment. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010;162:62–74. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman M., Maxim M.L., Rodríguez H., Rogers R.D. Complete dissolution and partial delignification of wood in the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate. Green Chem. 2009;11:646. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu S., Zhan H. Characteristics of demethylated wheat straw soda lignin and its utilization in lignin-based phenolic formaldehyde resins. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2001;35:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu F., Jiang J.X., Tang J.N., Su Y.Q. Fractional isolation and structural characterization of mild ball-milled lignin in high yield and purity from Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. Wood Sci. Technol. 2008;42:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita Y., Sasaki C., Nakamura Y. Development of efficient system for ethanol production from paper sludge pretreated by ball milling and phosphoric acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;79:250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zakzeski J., Bruijnincx P.C.A., Jongerius A.L., Weckhuysen B.M. The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3552–3599. doi: 10.1021/cr900354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L.W., Griggs B.F., Chen C.L., Gratzl J.S., Hse Y. Utilization of softwood kraft lignin as adhesive for the manufacture of reconstituted wood. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1994;14:127–145. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J.X., Chen D., Liao Zhu Y.H., Yuan H.D., Chen L., Z.H Liu X.M. Simultaneous wet ball milling and mild acid hydrolysis of rice hull. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou M., Huang K., Qiu X., Yang D. Content determination of phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl in lignin by aqueous phase potentiometric titration. CIESC J. 2012;63:258–265. [Google Scholar]