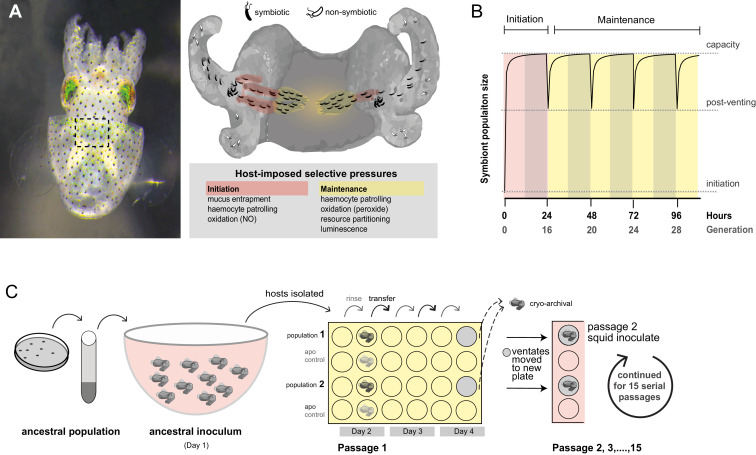

Figure 1. Host selection mechanisms that shape adaptive evolution by V. fischeri.

(A) Dorsal view of juvenile host E. scolopes (left) with box indicating the relative position of the ventrally situated symbiotic light organ. On the right, a schematic illustrating the stages at which host-imposed selection occurs during squid–V. fischeri symbiosis: host recruitment (mucus entrapment, aggregation at light organ pores), initiation of symbiosis (host defenses, including hemocyte engulfment and oxidative stress), and colonization and maintenance (nutrient provisioning, sanctioning of non-luminous cheaters, continued hemocyte patrolling, and daily purging). (B) Symbiont population growth modeled for a single passage on the basis of growth dynamics of V. fischeri ES114. Light-organ populations are initiated with as few as ~10 cells (Wollenberg and Ruby, 2009; Altura et al., 2013) or as much as 1% of the inoculum, but are reduced by 95% following venting of the light organ at dawn (every 24 hr) (Boettcher et al., 1996). Shaded areas represent night periods whereas light areas represent daylight, which induces the venting behavior. (C) Experimental evolution of V. fischeri under host selection as described in Schuster et al. (2010). Each ancestral V. fischeri population was prepared by recovering cells from five colonies, growing them to mid-log phase, and sub-culturing them into 100 mL filtered seawater at a concentration sufficient to colonize squid (≤20,000 CFU/mL). On day 1, ten un-colonized (non-luminous) juvenile squid were communally inoculated by overnight incubation, during which bacteria were subjected to the first host-selective bottleneck. Following venting of ~95% of the light organ population, the squid were separated into isolated lineages in individual wells of a 24-well polystyrene plate containing filtered sea water with intervening rows of squid from an un-inoculated control cohort, the aposymbiotc control (‘apo control’). Note that only two of the ten passage squid populations are shown. On days 2, 3, and 4, after venting, squid were rinsed and transferred into 2 mL fresh filtered seawater. Luminescence was measured at various intervals for each squid to monitor colonization and the absence of contamination in aposymbiotic control squid. On the fourth day, the squid and half of the ventate were frozen at −80°C to preserve bacteria, and the remaining 1 mL ventate was combined with 1 mL of fresh filtered seawater, and used to inoculate a new uncolonized 24-hr-old juvenile squid. The process continued for 15 squid only for those lineages in which squid were detectably luminous at 48 hr post inoculation.