Abstract

Background and Purpose

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a corticosteroid‐resistant airway inflammatory condition. Resveratrol exhibits anti‐inflammatory activities in COPD but has weak potency and poor pharmacokinetics. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of isorhapontigenin, another dietary polyphenol, as a novel anti‐inflammatory agent for COPD by examining its effects in vitro and pharmacokinetics in vivo.

Experimental Approach

Primary human airway epithelial cells derived from healthy and COPD subjects, and A549 epithelial cells were incubated with isorhapontigenin or resveratrol and stimulated with IL‐1β in the presence or absence of cigarette smoke extract. Effects of isorhapontigenin and resveratrol on the release of IL‐6 and chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL8), and the activation of NF‐κB, activator protein‐1 (AP‐1), MAPKs and PI3K/Akt/FoxO3A pathways were determined and compared with those of dexamethasone. The pharmacokinetic profiles of isorhapontigenin, after i.v. or oral administration, were assessed in Sprague–Dawley rats.

Key Results

Isorhapontigenin concentration‐dependently inhibited IL‐6 and CXCL8 release, with IC50 values at least twofold lower than those of resveratrol. These were associated with reduced activation of NF‐κB and AP‐1 and, notably, the PI3K/Akt/FoxO3A pathway, that was relatively insensitive to dexamethasone. In vivo, isorhapontigenin was rapidly absorbed with abundant plasma levels after oral dosing. Its oral bioavailability was approximately 50% higher than resveratrol.

Conclusions and Implications

Isorhapontigenin, an orally bioavailable dietary polyphenol, displayed superior anti‐inflammatory effects compared with resveratrol. Furthermore, it suppressed the PI3K/Akt pathway that is insensitive to corticosteroids. These favourable efficacy and pharmacokinetic properties support its further development as a novel anti‐inflammatory agent for COPD.

Abbreviations

- A549

human alveolar epithelial cells

- AP‐1

activator protein‐1

- AUC0→last

plasma exposure

- Cl

clearance

- Cmax

maximal plasma concentration

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CXCL8

chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 8

- ECL

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- F

absolute oral bioavailability

- FoxO3A

forkhead box O3A

- H2DCF‐DA

2′,7′‐dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- MTT0→last

mean transition time

- TBS

Tris balanced salt solution

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an escalating global health problem that is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality (Mannino and Buist, 2007; Vos et al., 2015). The massive healthcare burden associated with COPD has driven more studies in recent decades, which have significantly enhanced our understanding of the pathophysiology of COPD. It is now recognized that in COPD, there is an abnormal inflammatory response to inhaled irritants such as cigarette smoke in the lungs (Hogg, 2004; Barnes, 2009). The amplified release of inflammatory mediators and oxidants results in the destruction of peripheral airways and lung parenchyma, which leads to a progressive decline in lung function (Hogg, 2004).

Despite being a cornerstone therapy in another airway inflammatory disease, asthma, corticosteroids only show limited efficacy in COPD (Highland et al., 2003; To et al., 2010). This class of potent anti‐inflammatory agents is unable to significantly modulate the underlying inflammation in COPD to alter the course of the disease. Evidently, there is an urgent need for the development of novel anti‐inflammatory agents in COPD, which exert effects through pathways that are distinct from corticosteroids.

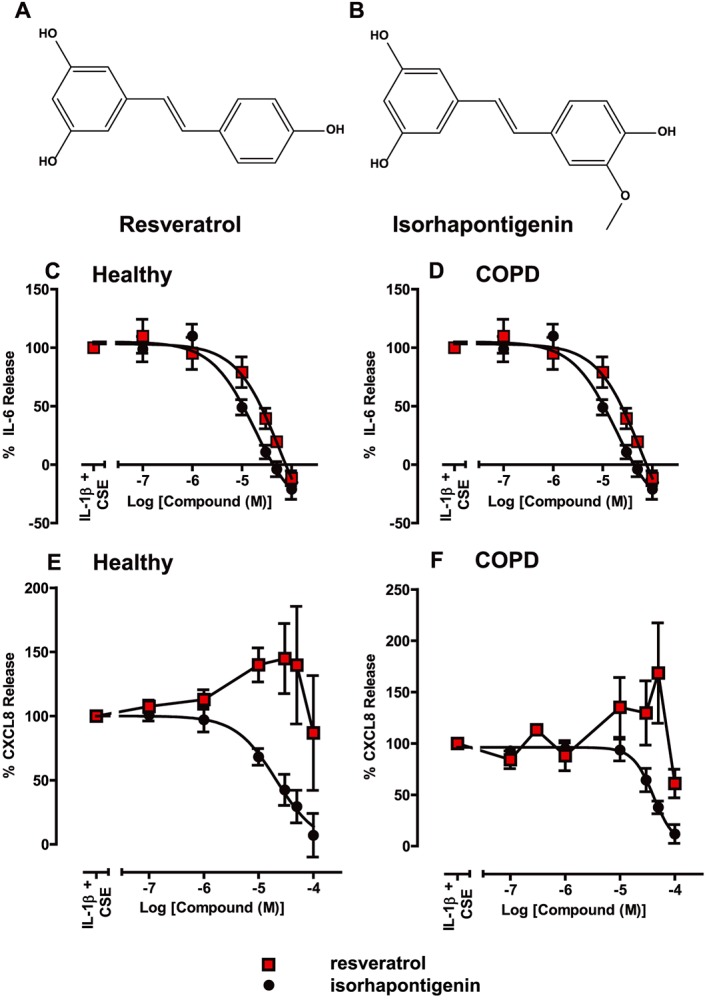

Resveratrol (trans‐3,5,4′‐trihydroxystilbene) (Figure 1A), a phytochemical present in various berries such as red grapes and blueberries, is a well‐known stilbene analogue, which has garnered significant attention due to the myriad pharmacological effects it possesses, including anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant effects (Baur and Sinclair, 2006; Bo et al., 2013). Several investigations have already confirmed the potential of resveratrol in COPD. When alveolar macrophages from cigarette smokers and COPD patients were treated with resveratrol, there was a marked reduction in the release of inflammatory markers [GM‐CSF and chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL8)] from both groups of patients, which was poorly inhibited by dexamethasone (Culpitt et al., 2003a,b). In addition, a mechanistic study in A549 lung carcinoma cells revealed that resveratrol inhibited the release of CXCL8 and GM‐CSF independently from the glucocorticoid receptor and exerted anti‐oxidative effects by reversing the cigarette smoke‐induced suppression of glutathione levels (Donnelly et al., 2004; Kode et al., 2008). However, the development of resveratrol as a therapeutic has been hindered by its weak potency and poor pharmacokinetics. Previous studies have shown that resveratrol is rapidly cleared from the body and poor oral bioavailability has been observed in clinical trials (Walle et al., 2004; Boocock et al., 2007; Das et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2016). These have prompted the exploration of other derivatives of resveratrol in search of molecules with better pharmacological properties. Isorhapontigenin (trans‐3,5,4′‐trihydroxy‐3′‐methoxystilbene) (Figure 1B) is a methoxylated analogue of resveratrol found naturally in grapes and can be isolated from a commonly used Chinese herb (Yao et al., 2003; Fernandez‐Marin et al., 2012). It has shown promising anti‐oxidative and anti‐cancer effects in several models (Kageura et al., 2001; Liu and Liu, 2004; Fang et al., 2013) and more recently demonstrated inhibitory effects on several important inflammatory signalling pathways, such as NF‐κB, activator protein‐1 (AP‐1), MAPKs and PI3K/Akt (Li et al., 2005; Gao et al., 2014). However, the effects of isorhapontigenin on airway inflammation and the underlying signalling pathways have not been investigated. Moreover, the pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin is limited to one preliminary study in mice (Fang et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Structure of stilbene analogues (A) resveratrol and (B) isorhapontigenin. Effects of stilbene analogues on the release of cytokines stimulated by 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β + 50% CSE in primary human airway epithelial cells. Primary cells from both (C, E) healthy and (D, F) COPD patients were treated with various concentrations of either resveratrol or isorhapontigenin for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β + 50% CSE for 24 h. Cell media were harvested and (C, D) IL‐6 and (E, F) CXCL8 measured by elisa (n = 5). Differences in response between cells from healthy subjects and COPD patients were analysed using Mann–Whitney U‐tests but were not significant.

This study evaluated the potential of isorhapontigenin as a therapy for COPD by assessing differences in its pharmacological effects compared with resveratrol in airway inflammation cell models. In addition, the pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin was profiled and compared with resveratrol to further evaluate its potential for medicinal application.

Methods

Cell culture

A549 cells (ATCC, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v.v‐1) FBS and 2 mM L‐glutamine as described previously (Donnelly et al., 2004). Primary human airway epithelial cells were cultured as monolayers in LHC‐9 media (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) on 3% (w.v‐1) collagen‐coated flasks. Cells were extracted from the lung tissues of healthy non‐smokers and COPD patients using methods described previously (Fenwick et al., 2015). COPD patients fulfilled the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease criteria (GOLD, 2016). The demographics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. All subjects provided informed written consent, and the study was approved by London‐Chelsea National Research Ethics Committee (09/H0801/85).

Table 1.

Demographics of subjects who provided primary epithelial cells

| Demographic | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy (n = 6) | COPD (n = 6) | |

| Age (years) | 68 ± 4 | 65 ± 4 |

| Gender (M : F) | 0:6 | 4:2 |

| Smoking history (pack years) | 0 | 40.2 ± 5.9 |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| FEV1% predicted | 90.7 ± 3.3 | 49.9 ± 16.7 |

| FVC (L) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| FVC % predicted | 102.8 ± 4.3 | 78.7 ± 17.8 |

| FEV1: FVC | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.05 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. One pack year represents 20 cigarettes per day for 1 year.

Prior to treatment, cells were cultured in treatment medium, serum‐free medium (A549 cells) or hydrocortisone‐free bronchial epithelial growth medium (primary cells) overnight or bronchial epithelial basal medium (primary cells western blot) for 6 h. All experiments were performed in these media.

Cell treatments

Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of compounds for 1 h before stimulation: 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for A549 cells and 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β + 50% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) for primary cells. All compound solutions were prepared by first dissolving in DMSO and subsequently diluted using the respective treatment medium. The concentrations of DMSO in the final solutions were ≤0.1%. CSE was prepared by bubbling mainstream smoke from Marlboro Red cigarettes into bronchial epithelial basal medium, followed by filtration using 0.2 μm filter and the concentration normalized by measuring absorbance at 320 nm and adjusted such that 100% CSE was designated as having an optical density of 0.15 nm (Wirtz and Schmidt, 1996).

Measurement of IL‐6 and CXCL8 release

Cell‐free supernatants were harvested, and the concentrations of IL‐6 and CXCL8 were measured using sandwich elisa as described previously (Tudhope et al., 2008). The detection limit of these assays was 32 pg·mL−1.

Measurement of luciferase activity

A549 cells stably transfected with the NF‐κB‐dependent luciferase reporter, 6κBtkluc.neo, were cultured as described previously (Donnelly et al., 2004). Luciferase activity was determined using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Southamptom, UK). The cells were first lysed using 20 μL of cell lysis buffer. Next, 40 μL of luciferase assay reagent was added, and the light emitted was recorded immediately using a FLUOstar OPTIMA microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Bucks, UK).

RNA extraction and real‐time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from A549 cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For reverse transcription, a master mix consisting of dNTP mix, random primers and MultiScribe™ recombinant moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA) was added to 500 ng of RNA. cDNA was synthesized from this mixture using a thermal cycler (G‐Storm, Somerset, UK) with the following conditions: 25°C for 10 min → 37°C for 120 min → 85°C for 5 min. cDNA was diluted to 5 ng·μL−1 using RNase‐free water to be used for subsequent assays. Gene expression was measured using the Taqman real‐time PCR on a 7500 Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK) as described previously (Fenwick et al., 2015). mRNA expression levels of the samples were calculated using their Ct values by interpolation from the standard curve constructed. The mRNA expression levels for all samples were normalized to the level of the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1.

Whole cell lysis and nuclear extraction

Whole cell lysis was carried out using Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2 EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% (v.v‐1) Triton X‐100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β‐glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 μg·mL−1 leupeptin, supplemented with additional protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail for 30 min on ice. The lysate was then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 15 min, and the supernatant was used for further assays.

Nuclear protein was extracted using the NE‐PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio‐Rad Protein Assay (Biorad, Hertfordshire, UK).

Western blotting

Cell lysates were diluted in Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma‐Aldrich, Dorset, UK), resolved using 4–12% Bis‐Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked with 5% (w.v‐1) non‐fat milk in Tris balanced salt solution (TBS) containing 0.1% (v.v‐1) Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature before they were incubated with the primary antibodies against β‐actin, TATA‐binding protein, forkhead box O3A (FoxO3A), p50, p65, phosphorylated and total IκBα, p38, JNK, ERK and Akt (Cell Signaling, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed and incubated with the corresponding anti‐rabbit or anti‐mouse horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies before detection using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The signal was captured on Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and developed using Imaging Developer (AFP Imaging, New York, NY, USA).

Intracellular ROS assay

A cell permeable probe, 2′,7′‐dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF‐DA), was used to assess the levels of intracellular ROS in the cells. Upon entering the cells, this probe becomes deacetylated by intracellular esterases to H2DCF, which is rapidly oxidized to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′‐dicholorodihydrofluorescein by ROS. Cells were washed with warm PBS, and 10 μM H2DCF‐DA was loaded into the cells by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. Following this, the fluorescence of each sample was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm. Background fluorescence was deducted from the measured fluorescence of each sample.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by determining the reduction of 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) dye to insoluble formazan crystals as described previously (Donnelly et al., 2004).

Pharmacokinetic study

Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). The rat pharmacokinetic study was executed in accordance with the animal handling protocols that were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Singapore (NUS). These experiments were performed in Singapore under local guidelines that align with the ARRIVE guidelines. Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (9–10 weeks old; weight = 300–350 g) were purchased from InVivos (Singapore) and housed in a specific pathogen‐free animal facility with 12 h light/dark cycle at the Comparative Medicine (NUS) (temperature = 22 ± 1°C; humidity = 60–70%). They were allowed ad libitum access to food and water throughout the study period. The jugular veins of the rats were cannulated for blood sampling and i.v. dosing according to a well‐established protocol in our laboratory (Yeo et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2015).

The isorhapontigenin was prepared for i.v. administration by dissolving the powder in 0.3 M 2‐hydroxypropyl β‐cyclodextrin (Wacker, Burghausen, Germany) 1 h before dosing while the oral suspension was prepared by suspending the powder in 0.3% (w.v‐1) carboxymethylcellulose just before dosing. L‐ascorbic acid [final concentration = 0.01% (w.v‐1)] was added to both formulations to ensure stability of the compound.

Five rats received a single bolus i.v. injection of isorhapontigenin at the dose of 30 μmol·kg−1 (7.74 mg·kg−1) while the other five rats received a single dose of isorhapontigenin 600 μmol·kg−1 (154.8 mg·kg−1), p.o. Serial blood samples were collected before dosing and at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 420 and 600 min after i.v. administration and at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 420, 540 and 720 min after p.o. administration. The blood samples were collected in tubes containing L‐ascorbic acid (final concentration = 0.8 mg·mL−1) to ensure stability. The samples were centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 min, and the plasma layer was retrieved and stored at −80°C until analysed. Following the study period, the animals were killed by exposure to CO2.

The analysis of concentrations of isorhapontigenin in the plasma samples was carried out using LC‐MS/MS on the Agilent 1290 Infinity Liquid Chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to ABSciex QTRAP® 5500 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) mass spectrometer equipped with TurboIon Spray™ (electrospray ionization) probe, which was controlled by the Analyst 1.5.2 software (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

The pharmacokinetic calculations were performed using WinNonlin standard version 1.0 (Scientific Consulting, Apex, NC, USA). Upon i.v. administration of isorhapontigenin ‘double‐peak phenomenon’ was observed in all rats, therefore, to estimate the apparent volume of distribution (V), V was calculated with the one‐compartment first‐order open model (C = C0 ⋅ e−k ⋅ t) using data from the first hour (Chen et al., 2016). All other pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by use of non‐compartmental analysis.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated, where ‘n’ represents the number of individual experiments or subjects. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism Version 5.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). The distribution of experimental data was first assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. If data were found to follow Gaussian distribution, parametric tests (two‐tailed unpaired t‐test for comparison between two groups or one way ANOVA for comparison among three or more groups) were carried out. For ANOVA, Tukey's post test was used to discern differences among all groups while the Bonferroni post test was used to compare with a control group. If data were not normally distributed, non‐parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test for comparison between two groups or Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's post test for comparison among three or more groups) were used. IC50 values were calculated by log transforming the concentration values followed by curve fitting using nonlinear regression using four parameter models (Y = Bottom + (Top‐Bottom)/(1 + 10^((LogIC50‐X)*HillSlope))) using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was achieved if the P value was <0.05. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015).

Materials

All chemicals, including resveratrol, were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich (Poole, UK) unless otherwise stated. Isorhapontigenin was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan).

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/2016 (Alexander et al., 2015a,b).

Results

Effects of resveratrol and isorhapontigenin on release of IL‐6 and CXCL8 from A549 cells and primary airway epithelial cells

To investigate the anti‐inflammatory effects of the stilbene analogues, primary human airway epithelial cells were used. Initial experiments were performed and showed that a combination of IL‐1β and 50% CSE gave a robust cytokine output above each of the components alone. A combination of 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β + 50% CSE stimulated the release of IL‐6 (unstimulated cells: 0.67 ± 0.36 ng·mL−1; stimulated cells: 2.40 ± 0.89 ng·mL−1, n = 5) and CXCL8 (unstimulated cells: 4.68 ± 1.86 ng·mL−1; stimulated cells: 15.24 ± 5.84 ng·mL−1, n = 5) in primary cells after 24 h whereas IL‐1β alone led to the release of 1.8 ± 0.6 ng·mL−1 IL‐6 and 10.1 ± 2.9 ng·mL−1 CXCL8.

IL‐6 release from stimulated primary cells was inhibited by both compounds in a concentration‐dependent manner (Figure 1C, D). Their inhibition profiles were similar with isorhapontigenin appearing to be more potent, but this was not statistically significant (Table 2). Cells derived from different patient groups did not show any difference in IC50 values (Table 2).

Table 2.

IC50 values of stilbene analogues for the inhibition of IL‐1β + CSE‐stimulated IL‐6 and CXCL8 release in primary airway epithelial cells from healthy and COPD patients

| Cytokine | Compound | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | COPD | ||

| IL‐6 | Isorhapontigenin | 17.3 ± 3.4 | 19.7 ± 9.1 |

| Resveratrol | 43.5 ± 17.4 | 56.5 ± 23.3 | |

| CXCL8 | Isorhapontigenin | 33.4 ± 14.3 | 45.9 ± 9.4 |

| Resveratrol | No inhibition | No inhibition | |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5).

CXCL8 release was modulated by the compounds in different ways (Figure 1E, F). Isorhapontigenin inhibited CXCL8 release from primary cells with an IC50 value that appeared to be slightly higher than that for IL‐6 release (Table 2) with no significant difference between cells from healthy subjects or COPD patients. This contrasted with the effects of resveratrol, which enhanced the release of CXCL8 in cells from both subject groups, and to this end, it was not possible to fit a curve to the data.

In order to ensure that cell viability was not contributing significantly to the anti‐inflammatory effects observed, MTT assays were performed on the cells after the supernatant was harvested. For isorhapontigenin and resveratrol, concentrations up to 100 μM did not have a significant effect on cell viability (>85%).

Effects of resveratrol and isorhapontigenin on inflammatory signalling pathways

In order to examine the mechanism(s) underlying the inhibitory effects of stilbene analogues observed, the activities of the various inflammatory pathways were investigated. Dexamethasone was also included in the study as a prototypical steroid control to uncover differences between the mechanisms of stilbene analogues and corticosteroid.

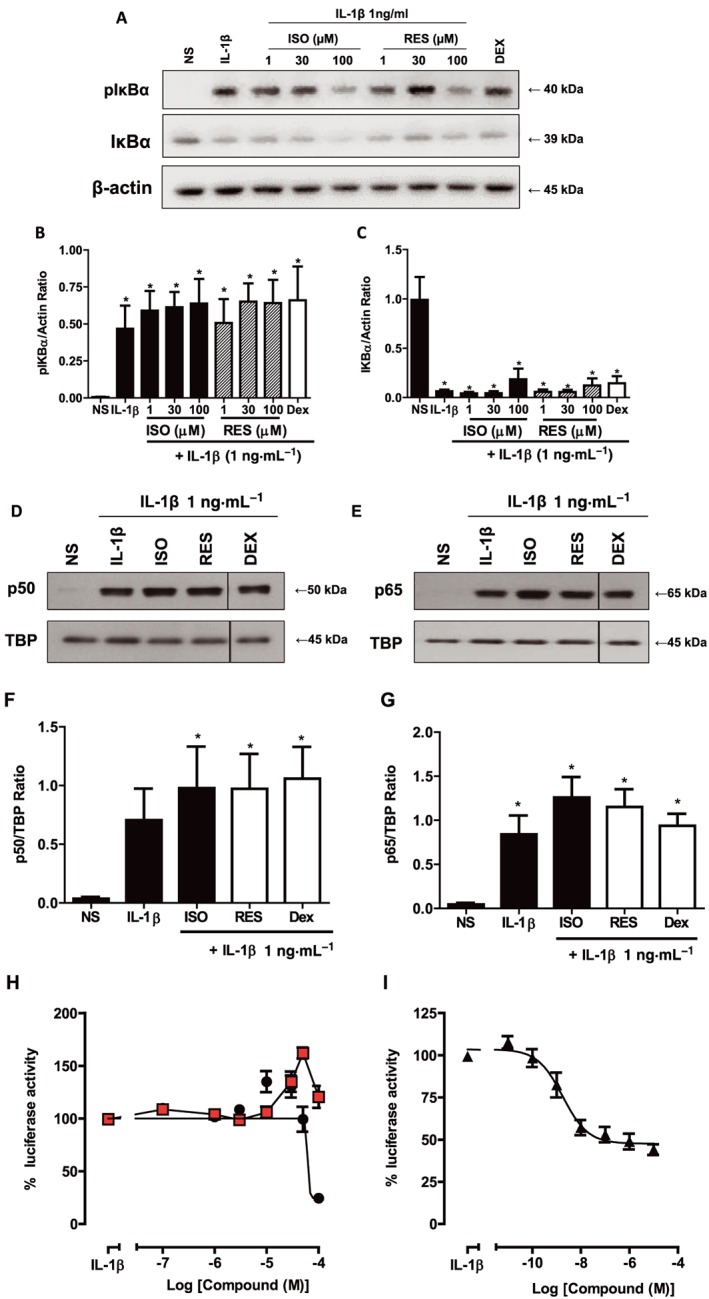

Effects on NF‐κB pathway in A549 cells

The effects of the stilbene analogues on the NF‐κB pathway were first examined by investigating the activation of a major protein IκBα. When the cells were stimulated with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β, there was an increase in phosphorylation of IκBα proteins, and correspondingly, the total IκBα levels were reduced after 10 min (Figure 2A). The compounds did not alter significantly the increased phosphorylation of IκBα (Figure 2A, B). However, IL‐1β induced a reduction in total IκBα protein that was not reversed by either stilbene (Figure 2A, C).

Figure 2.

Effects of stilbene analogues and dexamethasone on the NF‐κB pathway. (A) Representative blots and quantification of total pIκBα and IκBα protein expression in A549 cells treated with various concentrations of either isorhapontigenin (ISO) or resveratrol (RES) (1–100 μM) or 1 μM dexamethasone for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 10 min. IL‐1β induced an increase in levels of pIκBα (B), which was not altered by the compounds (n = 4) where * represents P < 0.05 for differences from non‐stimulated cells (NS) by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction. However, there was a suppression of expression of IκBα by all treatments where * indicates P < 0.05 for differences between NS cells and treatments (C). Nuclear protein expression of p50 (D, F) and p65 (E, G) were increased by stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 1 h and were not altered by the compounds (n = 3) where TBP is TATA box binding protein and used as a loading control and * represents P < 0.05 for differences from NS by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction. A549 cells stably transfected with NF‐κB reporter gene were treated with increasing concentrations of either ISO (●) or RES ( ) (H) or dexamethasone (I) for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 6 h. ISO reduced luciferase activity to nearly basal levels while RES showed minimal inhibitory effects and the maximum repression by dexamethasone was 60% (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM.

) (H) or dexamethasone (I) for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 6 h. ISO reduced luciferase activity to nearly basal levels while RES showed minimal inhibitory effects and the maximum repression by dexamethasone was 60% (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM.

As the effects of the compounds on IκBα were limited, nuclear translocation of the major subunits of NF‐κB, p50 and p65, was investigated to determine if resveratrol or isorhapontigenin had effects on downstream signalling. IL‐1β elicited an increase in nuclear levels of p50 and p65 at 60 min (Figure 2D–G). The compounds when used at 100 μM did not appear to have significant effect on this increased nuclear accumulation of p65 and p50 (Figure 2D–G). Dexamethasone (1 μM) was also ineffective at inhibiting this process, which is congruent with the observation reported in an earlier study (Newton et al., 1998).

As the stilbene analogues did not appear to inhibit the signal transduction processes leading to the nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 subunits, it may be possible that they affected further downstream pathways leading to disruption of NF‐κB transcriptional activity. To study the effect of the compounds on NF‐κB activity, A549 cells stably transfected with the NF‐κB luciferase reporter gene, 6κBtkluc.neo, were used. IL‐1β stimulation resulted in approximately 10‐fold increase in luciferase expression as measured by the increase in luminescence at 6 h. At the highest concentration (100 μM) used, isorhapontigenin inhibited this increase by more than 75% while resveratrol did not appear to have significant effect (Figure 2H). Although dexamethasone, the positive steroid control, was highly potent (IC50 = 2.1 ± 0.8 nM), its maximal inhibition was only approximately 60% (Figure 2I).

In summary, isorhapontigenin was able to reduce the NF‐κB activity induced by IL‐1β, but only at high concentrations, and this was effected through a pathway independent of IκBα and the nuclear accumulation of the p50 and p65 subunits.

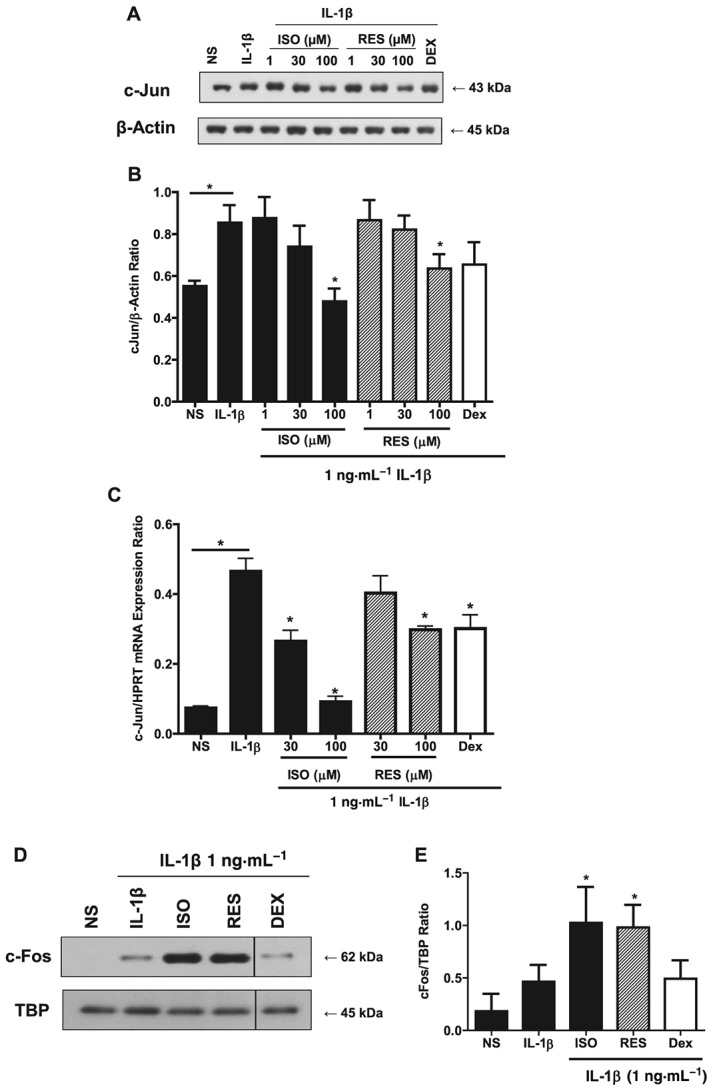

Effects on AP‐1 pathway in A549 cells

Having observed inhibitory effects on the NF‐κB transcription factor pathway, another group of important inflammatory transcription factors, AP‐1, was examined. The AP‐1 transcription factors are critical inflammatory mediators with rapid induction. To study the effect of the stilbene analogues on this pathway, the protein levels of the major members, c‐Jun and c‐Fos, were investigated. The total cellular levels of c‐Jun increased from baseline following 60 min exposure to IL‐1β (Figure 3A, B). When A549 cells were treated with stilbene analogues in this model for 1 h before IL‐1β stimulation, both isorhapontigenin and resveratrol suppressed activation in a concentration‐dependent manner (Figure 3A, B). Isorhapontigenin at the highest concentration (100 μM) reduced c‐Jun protein levels to baseline levels while resveratrol was less effective. The steroid control, dexamethasone, used at 1 μM, had no significant effect on c‐Jun expression.

Figure 3.

Effects of stilbene analogues and dexamethasone (DEX) on the AP‐1 pathway. (A) Representative blot and (B) quantification of total c‐Jun protein expression in A549 cells treated with various concentrations of isorhapontigenin (ISO) or resveratrol (RES) (1–100 μM) or 1 μM DEX for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 60 min. IL‐1β increased the expression of c‐Jun where * represents P < 0.05 for differences from non‐stimulated cells (NS). This stimulation was reduced by stilbene analogues and DEX (n = 5), where *indicates P < 0.05 for differences from IL‐1β stimulated cells by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction. (C) c‐Jun mRNA levels were significantly increased after IL‐1β stimulation (P < 0.05) for 30 min, and this was significantly attenuated by ISO (P < 0.05) and to a lesser extent by RES and DEX (n = 5) where * represents P < 0.05 as measured by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for differences from IL‐1β stimulation. (D) Representative blot and quantification (E) of total c‐Fos protein expression in A549 cells treated with 100 μM stilbene analogue or 1 μM DEX for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 60 min. IL‐1β increased the levels of c‐Fos, which was enhanced by stilbene analogues but dexamethasone had no effect (n = 4). Data are mean ± SEM, and * represents P < 0.05 as measured by ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Since this reduction in protein quantity could be due to alterations at the mRNA or protein levels, c‐Jun mRNA levels were studied using qRT‐PCR. IL‐1β stimulation for 30 min increased the expression of c‐Jun mRNA significantly to approximately threefold above baseline (Figure 3C). Isorhapontigenin concentration‐dependently repressed this increase, with 100 μM almost completely abrogating the increase (Figure 3C). Similar to the observation at protein levels, resveratrol appeared less effective than isorhapontigenin but did show a trend to inhibit expression, with a significant reduction of ~30% with 100 μM. Dexamethasone had a similar small effect on c‐Jun mRNA expression.

As c‐Fos could not be detected in the total cellular extract, its nuclear levels were studied instead. IL‐1β similarly elicited a marked increase in c‐Fos at 60 min following stimulation with IL‐1β (Figure 3D). In contrast to their effects on c‐Jun, the stilbene analogues significantly enhanced the IL‐1β stimulated increase in amount of nuclear c‐Fos levels (Figure 3D, E). Dexamethasone brought about a slight reduction in this protein.

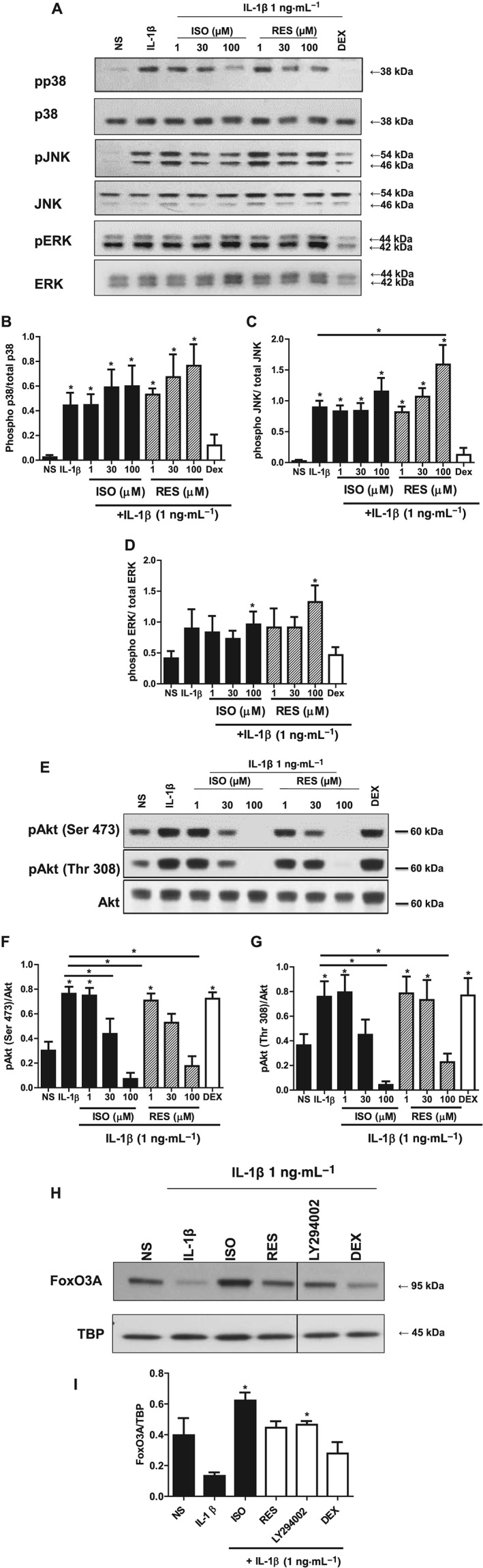

Effects on MAPK pathway in A549 cells

Since various transcription factors were modulated by the stilbene analogues, it is possible that important upstream inflammatory pathways such as the MAPKs were involved. IL‐1β elicited increased phosphorylation of the MAPK proteins, p38, JNK and ERK at 40 min (Figure 4A–D). It was found that the stilbene analogues did not have significant inhibitory effects on any of the MAPK pathways although the highest concentration of isorhapontigenin appeared to suppress phospho‐p38 slightly and resveratrol appeared to show a trend towards activation that was significant on the JNK pathway (Figure 4A, C). Dexamethasone inhibited the activation of all three proteins, and this was congruent with previous studies (Jang et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2014).

Figure 4.

Effects of stilbene analogues and dexamethasone (DEX) on the major intracellular inflammatory signalling pathways. (A) Representative blots and quantification of phosphorylated and total p38 (B), JNK (C) and ERK (D) protein expression in A549 cells treated with various concentrations of either isorhapontigenin (ISO) or resveratrol (RES) (1–100 μM) or 1 μM DEX for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β for 40 min. IL‐1β induced increase in levels of phosphorylated p38, JNK and ERK protein expression, which were suppressed by DEX but not stilbene analogues (n = 4). (E) Representative blots and quantification of phosphorylated Ser473 (F) or Thr308 (G) and total Akt protein expression in A549 cells treated with various concentrations of either ISO or RES (1–100 μM) or 1 μM DEX for 1 h before stimulation for 40 min. IL‐1β induced increase in levels of phosphorylated Akt (at Ser473 and Thr308) protein expression, which were suppressed by stilbene analogues and not by DEX (n = 5). (H) Representative blot of nuclear protein expression of FoxO3A and densitometry (I) showing reduction with IL‐1β at 60 min, and this reduction was prevented by ISO, RES and LY294002 but not DEX (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM where * represents P < 0.05, for differences from non‐stimulated cells (NS) using ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Effects on PI3K/Akt pathway in A549 cells

The PI3k/Akt pathway is another key mediator of inflammation. When A549 cells were stimulated with IL‐1β, the phosphorylation of Akt at both Ser473 and Thr308 increased at 40 min without any changes in total Akt levels (Figure 4E–G). When treated with the stilbene compounds for 1 h before IL‐1β stimulation, the increased phosphorylation of Akt at both sites was reduced in similar manner without any effect on total Akt levels (Figure 4E–G). Isorhapontigenin was the more effective analogue. At 30 μM, the activation of Akt was suppressed to levels approaching that seen in untreated cells at baseline, while 100 μM of isorhapontigenin further decreased activation to below baseline levels. The effects of resveratrol were similar and arrested the increased phosphorylation of Akt at 100 μM. Dexamethasone when used at the same concentration (1 μM), which potently reduced MAPK activation, did not suppress the activation of Akt. This shows that the stilbene analogues and dexamethasone were having distinct effects on inflammatory signalling pathways.

FoxO3A is a downstream effector of PI3K/Akt signalling involved in the release of inflammatory cytokines in airway epithelial cells (Ganesan et al., 2013). To establish whether the anti‐inflammatory effects of Akt inhibition were partly mediated through FoxO3A in the inflammation model used in this study, nuclear FoxO3A levels were examined. IL‐1β reduced nuclear levels of FoxO3A at 60 min, which is known to be a result of nuclear export following phosphorylation by Akt (Figure 4H, I). The stilbene analogues attenuated this reduction by IL‐1β, and isorhapontigenin appeared to be more effective than resveratrol (Figure 4H, I). The involvement of PI3K/Akt signalling was further confirmed by the ability of the pan PI3kinase inhibitor LY294002, to reverse the effects of IL‐1β. Dexamethasone, on the other hand, only slightly inhibited the IL‐1β‐induced reduction in nuclear FoxO3A, which was reflective of its weak effect on the PI3K/Akt pathway (Figure 4H, I).

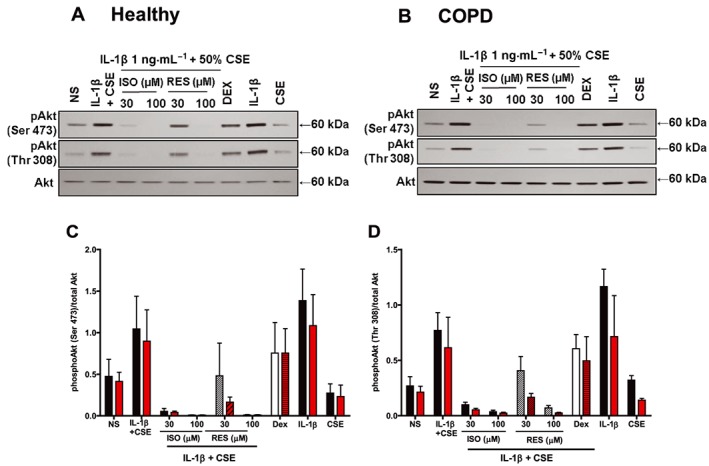

The key mechanism of stilbene analogues observed in A549 cells involving the inhibition of Akt activation was validated in primary airway epithelial cells. Primary airway epithelial cells from non‐smokers (Figure 5A) and COPD (Figure 5B) patients were used and stimulated with a combination of IL‐1β and 50% CSE for 60 min; the phosphorylation of Akt at both Ser473 and Thr308 increased evidently without any changes in total Akt levels (Figure 5C, D). There was no effect of CSE alone in these experiments.

Figure 5.

Effects of stilbene analogues and dexamethasone (DEX) on the PI3K/Akt pathway in primary airway epithelial cells. Representative blots of phosphorylated and total Akt protein expressions in primary airway epithelial cells from (A) healthy and (B) COPD patients treated with either isorhapontigenin (ISO) or resveratrol (RES) (30 and 100 μM) or 1 μM DEX for 1 h before stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β + CSE for 60 min, or either IL‐1β or CSE alone. IL‐1β increased the levels of phosphorylated Akt (at Ser473 and Thr308) protein expression, which was suppressed by stilbene analogues and to a lesser extent by DEX (n = 3). Quantification of (C) phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) and (D) phosphorylated Akt (Thr308) protein expression is presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3) where the black bars represent cells from healthy controls and the red bars represents cells from COPD patients.

When treated with the stilbene compounds for 1 h before stimulation, the increased phosphorylation of Akt at both sites were reduced in similar manner without any effect on total Akt levels. Isorhapontigenin appeared to be more potent than resveratrol as it reduced the activation state to basal levels at 30 μM while resveratrol only showed slight reduction. Dexamethasone, at 1 μM, had limited effect on the activation of Akt similar to the effects observed in A549 cells. In addition, IL‐1β was found to be the major driver for Akt activation while CSE had limited effect although it was required for enhanced release of cytokines from these cells. Furthermore, cells from the two subject groups did not show significant differences in their responses (Figure 5C, D).

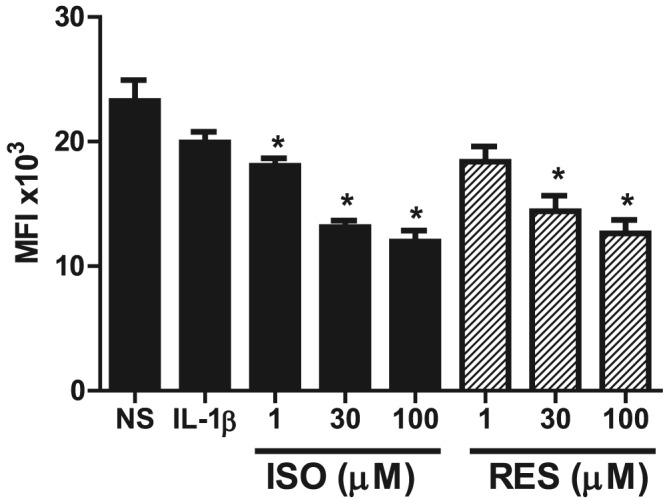

Effects on intracellular ROS levels

Intracellular ROS have pleiotropic effects and has been linked to activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (Ito and Barnes, 2009; To et al., 2010). To investigate if the stilbene analogues modulated the redox status in the A549 inflammatory model, cells were pretreated with the compounds for 1 h before stimulation with IL‐1β for 30 min (Figure 6). IL‐1β stimulation did not significantly alter the ROS levels compared with baseline using the H2DCF‐DA assay. However, isorhapontigenin and resveratrol concentration‐dependently reduced the ROS levels significantly by approximately 30%.

Figure 6.

Effects of stilbene analogues on intracellular ROS levels. A549 cells were treated with the various concentrations of isorhapontigenin (ISO) or resveratrol (RES) (1–100 μM) for 1 h followed by stimulation with 1 ng·mL−1 IL‐1β. After 30 min, 10 μM H2DCF‐DA, an intracellular oxidant indicator, was loaded and cells incubated for a further 30 min. ROS levels were significantly reduced by ISO and RES (n = 5). Data are mean ± SEM where *P < 0.05 compared with IL‐1β‐stimulated cells.

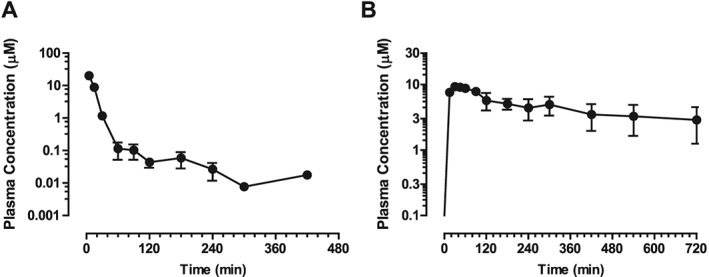

Pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin in rats

Upon bolus i.v. administration of isorhapontigenin at 30 μmol·kg−1 (7.74 mg·kg−1) in Sprague–Dawley rats, plasma isorhapontigenin levels first declined rapidly before a more prolonged terminal elimination phase where secondary peaks were observed from 90 min (Figure 7A). Appearance of secondary peaks suggests the involvement of enterohepatic recirculation, which has also been reported for resveratrol (Marier et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2016). Isorhapontigenin was eliminated rapidly, and its plasma level dropped below the lower limit of quantification (1 ng·mL−1 or 3.87 nM) of the LC‐MS/MS method in one sample collected at 90 min and two samples collected at 300 min post‐injection. However, isorhapontigenin became measurable again in the next sample collected from the same rat, probably due to the enterohepatic circulation. Such erratic pharmacokinetic behaviour makes the accurate calculation of plasma exposure (AUC0→last) and mean transition time (MTT0→last) difficult. To facilitate the estimation of AUC0→t and MTT, the plasma level of isorhapontigenin in these three samples was adjusted to the lower limit of quantification (1 ng·mL−1 or 3.87 nM). Of note, such approximation would overestimate the i.v. AUC0→t and MTT0→t to a very low extent, and it was also applied in a recent pharmacokinetic study of resveratrol (Chen et al., 2016). Isorhapontigenin was found to display a moderate V, MTT0→last and rather rapid clearance (Cl) (Table 3).

Figure 7.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of isorhapontigenin in Sprague–Dawley rats. Rats were administered (A) 30 μmol·kg−1 isorhapontigenin i.v. or (B) 600 μmol·kg−1 isorhapontigenin p.o. Blood was collected at specific time points and plasma analysed using LC‐MS/MS. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of isorhapontigenin

| Parameters | Route | |

|---|---|---|

| i.v. | p.o. | |

| Formulation | Solution | Suspension |

| Dose (μmol·kg−1) | 30 | 600 |

| V (mL·kg−1) | 830 ± 74 | – |

| AUC0→last (102 × min·μM) | 3.43 ± 0.23 | 32.4 ± 10.2 |

| Cl (mL·min−1·kg−1) | 89.2 ± 6.3 | – |

| MTT0→last (min) | 14.1 ± 1.1 | 268 ± 22 |

| Cmax (μg·mL−1) | – | 9.90 ± 1.03 |

| tmax (min) | – | 30–60 |

| F (%) | – | 47.2 ± 14.8 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 for i.v. and n = 5 for p.o. group).

When isorhapontigenin was administered through oral gavage as a suspension at 600 μmol·kg−1 (154.8 mg·kg−1), it was absorbed rapidly (Figure 7B), achieving maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) within the first hour after dosing. Isorhapontigenin was measurable in all post‐dosing plasma samples. The AUC0→last of isorhapontigenin was fairly abundant, and the absolute oral bioavailability (F) was relatively high (Table 3). Similar to i.v. dosing, secondary peaks were also observed from 180 min post‐dosing. Such phenomena have also been observed after oral administration of resveratrol and oxyresveratrol (Chen et al., 2016).

Discussion

Resveratrol has been described as a ‘miracle’ molecule due to its beneficial effects on various diseases including airway inflammation. However, its weak potency and pharmacokinetics are major barriers to its clinical application, and increasing attention is now focused on its analogues, which have superior pharmacological properties. This study systematically compared the anti‐inflammatory effects of resveratrol with another naturally occurring analogue, isorhapontigenin, to determine their relative potencies and the underlying mechanisms. The in vivo pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin were also described, for the first time, in a rat pharmacokinetic model.

Airway epithelial cells play a prominent role in the inflammation of COPD (Gao et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2003). They are one of the first cell types to come into contact with inhaled noxious stimuli, which leads to their stimulation and release of inflammatory mediators including IL‐6 and CXCL8 through the activation of multiple inflammatory signalling pathways such as MAPKs and PI3K/Akt (Gaffey et al., 2013; Lee and Yang, 2013; Moretto et al., 2012). These mediators are responsible for the recruitment and activation of other inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages and neutrophils, which contribute to the perpetuation of inflammation by releasing large amount of inflammatory mediators including cytokines and protease implicated in the pathophysiology of COPD.

The stilbene analogues altered the release of IL‐6 and CXCL8 stimulated by a combination of IL‐1β and CSE similarly in both healthy and COPD patients, implying effect through pathways that were not altered by disease state. On the other hand, these analogues showed slightly reduced potency or complete loss of efficacy in inhibition of CXCL8 release when compared with their effects on IL‐6 release. Such differential effects can be accounted by differences in signalling pathways regulating the release of IL‐6 and CXCL8 (Ge et al., 2010). It is of note that there is a greater variability in the release of CXCL8 from these cells and that this may be due to sampling from humans rather than using cell lines.

NF‐κB regulates the transcription of a wide array of inflammatory genes including IL‐6 and CXCL8 (Tak and Firestein, 2001). Isorhapontigenin showed marked inhibition of NF‐κB transcriptional activity but had little effect on upstream activation of IκBα or p50/p65 nuclear translocation. This implies that its NF‐κB inhibitory activities are likely downstream of NF‐κB nuclear translocation. It is possible that these downstream interactions may include effects on transcriptional co‐activators including histone deacetylases and p300 (Hoesel and Schmid, 2013; Zhong et al., 2002). Our data appears to contradict findings from previous studies that showed that resveratrol exerted its effects through the IκBα or p65 nuclear translocation pathways (Adams et al., 2005; Adhami et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2010). However, the similar lack of effect of dexamethasone on these pathways observed in our study corroborates that of a previous report using the same cell line and stimulus (Newton et al., 1998), supporting the notion that the mechanisms are specific to the cell type, stimuli and experimental conditions used. One interesting observation in our experiments is that dexamethasone resulted in a slight increase in IκBα levels. This has also been observed in a similar study on dexamethasone in A549 cells (Jang et al., 2007). However, this slight increase was insufficient to reduce the nuclear translocation of the NF‐κB subunits. It is unlikely that the stilbene analogues and dexamethasone share some of the same mechanisms because when their effects on NF‐κB transcription were examined, dexamethasone only showed a maximal inhibition of approximately 60% while isorhapontigenin could almost completely block transcription. It remains a possibility that these effects are cell culture and model specific, and therefore, further experiments would be required using an appropriate in vivo model of COPD; however at present, there are no good animal models that recapitulate the pathophysiology of this disease.

For the AP‐1 transcription factor pathway, isorhapontigenin showed the strongest inhibition of c‐Jun protein and mRNA levels, indicating that the reduced protein levels of c‐Jun could be largely due to reduced mRNA levels. For resveratrol and dexamethasone, regulation at the mRNA levels was less marked and the changes in protein levels could also be contributed by post‐translational modifications of c‐Jun such as inhibition of its phosphorylation (Caelles et al., 1997; Musti et al., 1997). In contrast to c‐Jun levels, the protein levels of the other major AP‐1 subunit, c‐Fos, were increased by the stilbene analogues. Despite this, the transcriptional activity of AP‐1 is likely to be reduced as c‐Fos requires heterodimerization with c‐Jun to form transcriptionally active dimers (Halazonetis et al., 1988). The resveratrol‐mediated reduction of c‐Jun protein levels in A549 cells observed in the present study could explain the abrogation of AP‐1 transcriptional activity by resveratrol in another study (Donnelly et al., 2004).

A clear distinction between the molecular mechanism of stilbene analogues and dexamethasone was evident in the activation of MAPK pathways, dexamethasone inactivated all three MAPK proteins, most likely through binding to the glucocorticoid receptors and inducing the dual‐specificity MAPK phosphatase 1 (Jang et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2014). On the other hand, the stilbene analogues did not significantly suppress the activation of MAPK proteins by IL‐1β. While isorhapontigenin showed marginal effects on the phosphorylation of MAPK proteins, resveratrol showed concentration‐dependent increase in phosphorylation of p38, JNK and ERK.

Isorhapontigenin appeared to show a larger inhibition of Akt phosphorylation than resveratrol, and this correlated well with its apparent more potent inhibition of the release of inflammatory cytokines. Previous studies have established the involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in the release of IL‐6 and CXCL8 from airway epithelial cells (Eda et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011). Furthermore, the PI3K/Akt pathway is activated in COPD cells (Mitani et al., 2015; To et al., 2010). One crucial observation in this study is that in contrast to its strong inhibition on MAPK proteins, dexamethasone only showed weak inhibitory effects on Akt activation in both A549 and primary cells. This Akt‐independent effect of dexamethasone has been reported in A549 cells and other cell types such as MCF‐7 breast cancer cells (Jang et al., 2007; Machuca et al., 2006). The activation of Akt phosphatases such as PP2A and PHLPP is an unlikely mechanism since these enzymes show higher specificity for one phosphorylation site only and would not cause the observed uniform reduction in both phosphorylation sites of Akt (Andjelkovic et al., 1996; Brognard et al., 2007; Stambolic et al., 1998). The direct kinases of Akt, PDK‐1 and mTORC2, are also unlikely targets due to the same reason described above. It is likely that the stilbene analogues targeted the regulation of PIP3 levels such as directly on PI3K. There are enzymatic studies which have shown that resveratrol and its analogue, piceatannol, are direct inhibitors of PI3K (Choi et al., 2010; Frojdo et al., 2007). However, the lack of an appropriate cellular PI3K assay impedes validation of this target in cells.

Downstream of the PI3K/Akt pathway, FoxO3A is a major target that becomes phosphorylated, leading to cytoplasmic retention, ubiquitination and eventually degradation (Huang and Tindall, 2011). Reduced nuclear levels of FoxO3A in COPD airway epithelial cells has been shown to promote inflammation and oxidative stress by increasing the release of CXCL8 and reducing levels of antioxidants such as manganese superoxide dismutase (Ganesan et al., 2013; Kops et al., 2002). The MAPKs and PI3K/Akt pathways are also associated with the transcription factors described earlier. It appears that NF‐κB activity is dependent on both the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways as both dexamethasone and isorhapontigenin could reduce its activity. These links have also been shown in other studies using the same cell lines (Donnelly et al., 2004; Jang et al., 2007; Jung et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2011; Newton et al., 1998).

ROS has been implicated in the activation of PI3K/Akt pathway (Ito et al., 2007). Although IL‐1β did not increase ROS levels in our study, the stilbene analogues, in particular isorhapontigenin, were effective in reducing the levels of ROS. This could be the reason underlying the ability of stilbene analogues to reduce Akt phosphorylation below baseline. One of the factors accounting for the higher antioxidant effect of isorhapontigenin compared with resveratrol is the additional meta‐methoxy group in its structure, which has been associated with increased antioxidant potential (Hasiah et al., 2011).

The pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin were favourable. Using data obtained from our recent study using the same experimental model (Chen et al., 2016), a parallel comparison between the pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin and resveratrol could be carried out. The Cl and MTT0→t of isorhapontigenin was comparable with resveratrol (Cl: 89.2 ± 6.3 mL·min−1·kg−1 vs. 107.4 ± 8.3 mL·min−1·kg−1; MTT0→last: 14.1 ± 1.1 vs. 11.1 ± 0.8 two‐tailed t‐test: P > 0.05). Despite having similar i.v. pharmacokinetics, the oral pharmacokinetics of isorhapontigenin were better than resveratrol. Its F and dose‐normalized AUC0→last were respectively twofold and 2.5‐fold greater than resveratrol (F: 47.2 ± 14.8% vs. 22.3 ± 1.9%; dose‐normalized AUC0→last: 5.39 ± 1.69 min·g−1·mL−1 vs. 2.08 ± 0.18 min·g−1·mL−1; Mann–Whitney test: P < 0.05). Its MTT0→last was longer (MTT0→last: 268 ± 2 min vs. 185 ± 22 min; two‐tailed unpaired t‐test: P < 0.05) and dose‐normalized Cmax was higher although statistical significance was not achieved (dose‐normalized Cmax: 16.5 ± 1.7 g·mL−1 vs. 11.0 ± 1.8 g·mL−1; two‐tailed unpaired t‐test: P > 0.05). Based on our studies, at least 30% inhibition of IL‐6 release can be attained through a single oral dose of isorhapontigenin. From these data, although rather high concentrations of isorhapontigenin are required to elicit anti‐inflammatory responses in airway epithelial cells, similar concentrations appear to be bioavailable following oral dosing. However, future drug development may suggest that an inhaled route could provide better drug delivery locally at the concentrations required.

In summary, our study has established that isorhapontigenin is a promising anti‐inflammatory agent for COPD, with cytokine inhibitory effects that were achieved through modulation of the corticosteroid‐insensitive PI3K/Akt pathway. In addition, it was an orally bioavailable dietary polyphenol with favourable pharmacokinetic profiles. Such superior potency and pharmacokinetics compared with resveratrol warrants further development of isorhapontigenin as a novel anti‐inflammatory agent for COPD.

Author contributions

S.C.M.Y. performed all the experiments, statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of manuscript. P.S.F. isolated the primary human airway epithelial cells and assisted in the optimization of in vitro experiments and manuscript preparation. P.J.B. advised on the design of in vitro experiments, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. H.S.L. was responsible for animal ethics and guided the in vivo experiments, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. L.E.D. was responsible for human ethics, patient selection, design of in vitro experiments, analyses and manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London and the Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (R‐148‐000‐215‐112) grant from Ministry of Education, Singapore. S.C.M.Y. is a recipient of the President's Graduate Fellowship awarded by National University of Singapore.

Yeo, S. C. M. , Fenwick, P. S. , Barnes, P. J. , Lin, H. S. , and Donnelly, L. E. (2017) Isorhapontigenin, a bioavailable dietary polyphenol, suppresses airway epithelial cell inflammation through a corticosteroid‐independent mechanism. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174: 2043–2059. doi: 10.1111/bph.13803.

References

- Adams M, Pacher T, Greger H, Bauer R (2005). Inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis by stilbenoids from Stemona species. J Nat Prod 68: 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhami VM, Afaq F, Ahmad N (2003). Suppression of ultraviolet B exposure‐mediated activation of NF‐kappaB in normal human keratinocytes by resveratrol. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 5: 74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Cidlowski JA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Nuclear hormone receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5956–5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andjelkovic M, Jakubowicz T, Cron P, Ming XF, Han JW, Hemmings BA (1996). Activation and phosphorylation of a pleckstrin homology domain containing protein kinase (RAC‐PK/PKB) promoted by serum and protein phosphatase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 5699–5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ (2009). The cytokine network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 41: 631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur JA, Sinclair DA (2006). Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5: 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo S, Ciccone G, Castiglione A, Gambino R, De Michieli F, Villois P et al. (2013). Anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant effects of resveratrol in healthy smokers a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial. Curr Med Chem 20: 1323–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boocock DJ, Faust GE, Patel KR, Schinas AM, Brown VA, Ducharme MP et al. (2007). Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 16: 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brognard J, Sierecki E, Gao T, Newton AC (2007). PHLPP and a second isoform, PHLPP2, differentially attenuate the amplitude of Akt signaling by regulating distinct Akt isoforms. Mol Cell 25: 917–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caelles C, Gonzalez‐Sancho JM, Munoz A (1997). Nuclear hormone receptor antagonism with AP‐1 by inhibition of the JNK pathway. Genes Dev 11: 3351–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Yeo SC, Elhennawy MG, Xiang X, Lin HS (2015). Determination of naturally occurring resveratrol analog trans‐4,4′‐dihydroxystilbene in rat plasma by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry: application to a pharmacokinetic study. Anal Bioanal Chem 407: 5793–5801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Yeo SCM, Elhennawy MGAA, Lin H‐S (2016). Oxyresveratrol: a bioavailable dietary polyphenol. J Funct Foods 22: 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Kim JE, Song NR, Son JE, Hwang MK, Byun S et al. (2010). Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase is a novel target of piceatannol for inhibiting PDGF‐BB‐induced proliferation and migration in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 85: 836–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpitt SV, Rogers DF, Fenwick PS, Shah P, De Matos C, Russell RE et al. (2003a). Inhibition by red wine extract, resveratrol, of cytokine release by alveolar macrophages in COPD. Thorax 58: 942–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpitt SV, Rogers DF, Shah P, De Matos C, Russell REK, Donnelly LE et al. (2003b). Impaired inhibition by dexamethasone of cytokine release by alveolar macrophages from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Lin HS, Ho PC, Ng KY (2008). The impact of aqueous solubility and dose on the pharmacokinetic profiles of resveratrol. Pharm Res 25: 2593–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly LE, Newton R, Kennedy GE, Fenwick PS, Leung RH, Ito K et al. (2004). Anti‐inflammatory effects of resveratrol in lung epithelial cells: molecular mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L774–L783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda H, Burnette BL, Shimada H, Hope HR, Monahan JB (2011). Interleukin‐1beta‐induced interleukin‐6 production in A549 cells is mediated by both phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase and interleukin‐1 receptor‐associated kinase‐4. Cell Biol Int 35: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Cao Z, Hou Q, Ma C, Yao C, Li J et al. (2013). Cyclin d1 downregulation contributes to anticancer effect of isorhapontigenin on human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 12: 1492–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick PS, Macedo P, Kilty IC, Barnes PJ, Donnelly LE (2015). Effect of JAK inhibitors on release of CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 from human airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 10: e0128757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Marin MI, Guerrero RF, Garcia‐Parrilla MC, Puertas B, Richard T, Rodriguez‐Werner MA et al. (2012). Isorhapontigenin: a novel bioactive stilbene from wine grapes. Food Chem 135: 1353–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frojdo S, Cozzone D, Vidal H, Pirola L (2007). Resveratrol is a class IA phosphoinositide 3‐kinase inhibitor. Biochem J 406: 511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey K, Reynolds S, Plumb J, Kaur M, Singh D (2013). Increased phosphorylated p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase in COPD lungs. Eur Respir J 42: 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S, Unger BL, Comstock AT, Angel KA, Mancuso P, Martinez FJ et al. (2013). Aberrantly activated EGFR contributes to enhanced IL‐8 expression in COPD airways epithelial cells via regulation of nuclear FoxO3A. Thorax 68: 131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Chen L, Li J, Zhang D, Fang Y, Huang H et al. (2014). Isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibited cell transformation by inducing G0/G1 phase arrest via increasing MKP‐1 mRNA stability. Oncotarget 5: 2664–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Li L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ et al. (2015). Bronchial epithelial cells: the key effector cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Respirology 20: 722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Q, Moir LM, Black JL, Oliver BG, Burgess JK (2010). TGFbeta1 induces IL‐6 and inhibits IL‐8 release in human bronchial epithelial cells: the role of Smad2/3. J Cell Physiol 225: 846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD (2016). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPDGlobal initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease.

- Halazonetis TD, Georgopoulos K, Greenberg ME, Leder P (1988). c‐Jun dimerizes with itself and with c‐Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell 55: 917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasiah AH, Ghazali AR, Weber JF, Velu S, Thomas NF, Inayat Hussain SH (2011). Cytotoxic and antioxidant effects of methoxylated stilbene analogues on HepG2 hepatoma and Chang liver cells: Implications for structure activity relationship. Hum Exp Toxicol 30: 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highland KB, Strange C, Heffner JE (2003). Long‐term effects of inhaled corticosteroids on FEV1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A meta‐analysis Annals of internal medicine 138: 969–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoesel B, Schmid JA (2013). The complexity of NF‐kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer 12: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC (2004). Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet 364: 709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Tindall DJ (2011). Regulation of FoxO protein stability via ubiquitination and proteasome degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 1961–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Barnes PJ (2009). COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest 135: 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Caramori G, Adcock IM (2007). Therapeutic potential of phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase inhibitors in inflammatory respiratory disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang BC, Lim KJ, Suh MH, Park JG, Suh SI (2007). Dexamethasone suppresses interleukin‐1beta‐induced human beta‐defensin 2 mRNA expression: involvement of p38 MAPK, JNK, MKP‐1, and NF‐kappaB transcriptional factor in A549 cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 51: 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YJ, Isaacs JS, Lee S, Trepel J, Neckers L (2003). IL‐1beta‐mediated up‐regulation of HIF‐1alpha via an NFkappaB/COX‐2 pathway identifies HIF‐1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 17: 2115–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageura T, Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Toguchida I, Harima S, Oda M et al. (2001). Inhibitors from rhubarb on lipopolysaccharide‐induced nitric oxide production in macrophages: structural requirements of stilbenes for the activity. Bioorg Med Chem 9: 1887–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kode A, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Yang SR, Megson IL, Rahman I (2008). Resveratrol induces glutathione synthesis by activation of Nrf2 and protects against cigarette smoke‐mediated oxidative stress in human lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L478–L488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops GJPL, Dansen TB, Polderman PE, Saarloos I, Wirtz KWA, Coffer PJ et al. (2002). Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature 419: 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I‐T, Yang C‐M (2013). Inflammatory signalings involved in airway and pulmonary diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2013: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HL, Wang AB, Huang Y, Liu DP, Wei C, Williams GM et al. (2005). Isorhapontigenin, a new resveratrol analog, attenuates cardiac hypertrophy via blocking signaling transduction pathways. Free Radic Biol Med 38: 243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Cheng HW, Ma HP, Wu CH, Hong CY, Chen BC (2011). Thrombin induces NF‐kappaB activation and IL‐8/CXCL8 expression in lung epithelial cells by a Rac1‐dependent PI3K/Akt pathway. J Biol Chem 286: 10483–10494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu G (2004). Isorhapontigenin and resveratrol suppress oxLDL‐induced proliferation and activation of ERK1/2 mitogen‐activated protein kinases of bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem Pharmacol 67: 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PL, Tsai JR, Charles AL, Hwang JJ, Chou SH, Ping YH et al. (2010). Resveratrol inhibits human lung adenocarcinoma cell metastasis by suppressing heme oxygenase 1‐mediated nuclear factor‐kappaB pathway and subsequently downregulating expression of matrix metalloproteinases. Mol Nutr Food Res 54 (Suppl 2): S196–S204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca C, Mendoza‐Milla C, Córdova E, Mejía S, Covarrubias L, Ventura J et al. (2006). Dexamethasone protection from TNF‐alpha‐induced cell death in MCF‐7 cells requires NF‐kappaB and is independent from AKT. BMC Cell Biol 7: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Buist AS (2007). Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 370: 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marier JF, Vachon P, Gritsas A, Zhang J, Moreau JP, Ducharme MP (2002). Metabolism and disposition of resveratrol in rats: extent of absorption, glucuronidation, and enterohepatic recirculation evidenced by a linked‐rat model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani A, Ito K, Vuppusetty C, Barnes PJ, Mercado N (2015). Restoration of corticosteroid sensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193: 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto N, Bertolini S, Iadicicco C, Marchini G, Kaur M, Volpi G et al. (2012). Cigarette smoke and its component acrolein augment IL‐8/CXCL8 mRNA stability via p38 MAPK/MK2 signaling in human pulmonary cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L929–L938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musti AM, Treier M, Bohmann D (1997). Reduced ubiquitin‐dependent degradation of c‐Jun after phosphorylation by MAP kinases. Science 275: 400–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Hart LA, Stevens DA, Bergmann M, Donnelly LE, Adcock IM et al. (1998). Effect of dexamethasone on interleukin‐1beta‐(IL‐1beta)‐induced nuclear factor‐kappaB (NF‐kappaB) and kappaB‐dependent transcription in epithelial cells. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS 254: 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel IS, Roberts NJ, Lloyd‐Owen SJ, Sapsford RJ, Wedzicha JA (2003). Airway epithelial inflammatory responses and clinical parameters in COPD. Eur Respir J 22: 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, King EM, Chandrasekhar A, Newton R (2014). Roles for the mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase, DUSP1, in feedback control of inflammatory gene expression and repression by dexamethasone. J Biol Chem 289: 13667–13679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T et al. (1998). Negative regulation of PKB/Akt‐dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell 95: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, Firestein GS (2001). NF‐κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 107: 7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To Y , Ito K, Kizawa Y, Failla M, Ito M, Kusama T et al. (2010). Targeting phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase‐δ with theophylline reverses corticosteroid insensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudhope SJ, Finney‐Hayward TK, Nicholson AG, Mayer RJ, Barnette MS, Barnes PJ et al. (2008). Different mitogen‐activated protein kinase‐dependent cytokine responses in cells of the monocyte lineage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324: 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B (2015). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990‐2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England 386: 743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walle T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE Jr, Walle UK (2004). High absorption but very low bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans. Drug Metab Dispos 32: 1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz HR, Schmidt M (1996). Acute influence of cigarette smoke on secretion of pulmonary surfactant in rat alveolar type II cells in culture. Eur Respir J 9: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao CS, Lin M, Liu X, Wang YH (2003). Stilbenes from Gnetum cleistostachyum. Acta Chimica Sinica 61: 1331–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo SC, Ho PC, Lin HS (2013). Pharmacokinetics of pterostilbene in Sprague–Dawley rats: the impacts of aqueous solubility, fasting, dose escalation, and dosing route on bioavailability. Mol Nutr Food Res 57: 1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S (2002). The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF‐kappa B determines its association with CBP/p300 or HDAC‐1. Mol Cell 9: 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]