Abstract

Background and Purpose

Cloxyquin (5‐cloroquinolin‐8‐ol) has been described as an activator of TRESK (K2P18.1, TWIK‐related spinal cord K+ channel) background potassium channel. We have examined the specificity of the drug by testing several K2P channels. We have investigated the mechanism of cloxyquin‐mediated TRESK activation, focusing on the differences between the physiologically relevant regulatory states of the channel.

Experimental Approach

Potassium currents were measured by two‐electrode voltage clamp in Xenopus oocytes and by whole‐cell patch clamp in mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons.

Key Results

Cloxyquin (100 µM) activated mouse and human TRESK 4.4 ± 0.3 (n = 28) and 3.9 ± 0.3‐fold (n = 8), respectively. The drug selectively targeted TRESK in the K2P channel family and exerted state‐dependent effects. TRESK was potently activated by cloxyquin in the resting state. However, after robust activation of the current by the calcium signal, evoked by stimulation of Gq‐coupled receptors, the compound did not influence mouse TRESK and only slightly affected the human channel. The constitutively active mutant channels, mimicking the dephosphorylated state (S276A) or containing altered channel pore (F156A and F364A), were not further stimulated by cloxyquin. In a subpopulation of isolated DRG neurons, cloxyquin substantially activated the background potassium current.

Conclusions and Implications

Cloxyquin activates TRESK by a Ca2+/calcineurin‐independent mechanism. The drug is specific for TRESK within the K2P channel family and useful for studying TRESK currents in native cells. The state‐dependent pharmacological profile of this channel should be considered in the development of therapeutics for migraine and other nociceptive disorders.

Abbreviations

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- hERG

human ether‐à‐go‐go‐related gene

- K2P

two‐pore domain K+ channel

- Kir

inwardly‐rectifying K+ channel

- Kv

voltage‐gated K+ channel

Introduction

Leak potassium currents are responsible for the resting membrane potential and play a role in the regulation of cellular excitability. K2P channels are the molecular correlates of the background (leak) potassium current. To date, 15 mammalian K2P subunits have been identified. They are regulated by a variety of physico‐chemical factors and signalling pathways (for review see Enyedi and Czirják, 2010).

TRESK (also known as K2P18.1 channel; Alexander et al., 2015a) was originally cloned from the human spinal cord (Sano et al., 2003). Under resting conditions, the channel has low activity because of the constitutive phosphorylation of its regulatory serine residues. Elevation of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration activates TRESK. The effect is indirect, mediated by the calcium/calmodulin‐dependent phosphatase, calcineurin (Czirják et al., 2004). We have previously shown that S264, S274 and S276 serine residues are the targets of calcineurin in mouse TRESK (mTRESK), and these amino acids are also conserved in the human orthologue (Czirják et al., 2004). After the cessation of the stimulation by calcineurin, rephosphorylation of these residues by PKA and microtubule affinity‐regulating kinases slowly returns the channel to the resting state (Czirják and Enyedi, 2010; Braun et al., 2011).

The expression of TRESK is highest in the primary sensory neurons of the dorsal root (Yoo et al., 2009) and trigeminal ganglia (Bautista et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2009). Single‐channel and whole‐cell patch clamp studies have confirmed that TRESK is a major component of the background potassium current in primary sensory neurons (Kang and Kim, 2006). It is a plausible hypothesis that the channel modulates the activity of different sensory pathways and the disruption of this modulatory effect can result in pathophysiological states by perturbing the excitability of sensory neurons.

In order for the physiological role of TRESK to be examined, appropriate pharmacological tools are needed for selective modulation of the channel. Local (lidocaine, bupivacaine and benzocaine) and volatile (halothane, isoflurane and sevoflurane) anaesthetics can modulate TRESK; however, other K2P channels are also sensitive to these compounds. TRESK, similar to other K2P channels, is insensitive to classic potassium channel blockers, tetraethylammonium, apamin and 4‐aminopyridine (for review, see Enyedi and Czirják, 2015). The K2P channels possess a peculiar structural element, the extracellular cap domain, which restricts access to the channel pore (Brohawn et al., 2012; Miller and Long, 2012). This structure may contribute to the lack of specific high‐affinity modulators (venoms or toxins) for K2P channels.

In a recent high‐throughput study, the anti‐amoebic drug cloxyquin was described as an activator of TRESK (Wright et al., 2013). Cloxyquin did not have an effect on the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir1.1 or on the voltage‐gated potassium channel human ether‐à‐go‐go‐related gene (hERG; also known as KV11.1). However, the mechanism of action and the specificity of the drug in the K2P channel family have not been examined. If cloxyquin acts directly on the channel (and not through the modulation of signalling pathways) and it is specific for TRESK, then cloxyquin and derivative compounds can be used to identify and modulate TRESK in native cells. In this study, we have determined the sensitivity of a wide range of K2P channels to cloxyquin and investigated the mechanism of cloxyquin‐mediated TRESK activation.

Methods

Plasmids, cRNA synthesis

The cloning of mouse TWIK‐2 (K2P6.1), TASK‐1, TASK‐2 and TASK‐3 (K2P3.1, K2P5.1 and K2P9.1 respectively), TREK‐2 (K2P10.1), TALK‐1 (K2P16.1), THIK‐1 (K2P13.1), TRESK (K2P18.1) and human TRESK channels has been described previously (Czirják et al., 2004; Czirják and Enyedi, 2006b). The plasmids coding mouse TREK‐1 (K2P2.1) and TRAAK (K2P4.1) channels were kindly provided by Professor M. Lazdunski and Dr F. Lesage. mTRESK S276A, mouse PQAVAD, hTRESK S264A mutant and PQAAAS mutants have been described previously (Czirják et al., 2004; Czirják and Enyedi, 2014). The F156A, F364A double mutant of mTRESK was created with the QuikChange site‐directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fidelity of the mutant channels was verified via automated sequencing. The plasmids were linearized and used for in vitro cRNA synthesis using the Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE™ T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The structural integrity of the RNA was checked on denaturing agarose gels.

Animal husbandry, preparation and microinjection of Xenopus oocytes, isolation of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons

Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared as previously described (Czirják and Enyedi, 2002). For expression of the different channels, oocytes were injected with 57 pg‐4 ng of cRNA (depending on the channel type) 1 day after defolliculation with 50 nL of the appropriate RNA solution. Injection was performed with the Nanolitre Injector (World Precision Instruments, Saratosa, FL, USA). Xenopus laevis frogs were housed in 50 L tanks with continuous filtering and water circulation. The room temperature was 19°C. Frogs were anaesthetized with 0.1% tricaine solution and killed by decerebration and pithing. Twenty‐seven frogs were used for the experiments.

DRG neurons were isolated from FVB/Ant mice obtained from the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Budapest, Hungary). Six female mice (of 3 months‐old) were used for the experiments. The animals used in the study were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water in an specific pathogen free (SPF) animal facility. Mice were killed humanely by CO2 exposure (CO2 was applied until the animals died). DRGs were dissected from the thoracic and lumbar levels of the spinal cord and collected in sterile PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) at 4°C. Ganglia were incubated in PBS containing 2 mg·mL−1 collagenase enzyme (type I; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) for 30 min with gentle shaking at 37°C. For further details of the isolation and culturing of the cells, see Braun et al. (2015). All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with state laws and institutional regulations. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Semmelweis University (approval ID: XIV‐I‐001/2154‐4/2012). Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015).

Two‐electrode voltage clamp and patch clamp measurements

Two‐electrode voltage clamp experiments were performed 2–3 days after the microinjection of cRNA into Xenopus oocytes, as previously described (Czirják et al., 2004). For the indicated number of measurements (n), the oocytes were derived from at least two frogs, but usually three frogs in each experiment. The holding potential was 0 mV. Background potassium currents were measured at the end of 300‐ms‐long voltage steps to −100 mV applied every 4 s. The low‐potassium recording solution contained (in mM): NaCl 95.4, KCl 2, CaCl2 1.8 and HEPES 5 (pH 7.5, adjusted by NaOH). The high‐potassium solution contained 80 mM K+ (78 mM NaCl of the low‐potassium solution was replaced with KCl). For measurement of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK currents, the high potassium solution contained 40 mM K+. Solutions were applied to the oocytes using a gravity‐driven perfusion system. Experiments were performed at room temperature (21 °C). Data were analysed by pCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Whole‐cell patch clamp experiments were performed as described previously (Lengyel et al., 2016). Isolated DRG neurons were used for the experiments 1–2 days after isolation. Cut‐off frequency of the eight‐pole Bessel filter was adjusted to 200 Hz; data were acquired at 1 kHz. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 0.05 EGTA, 1 Na2‐ATP, 0.1 Na2‐GTP and 10 HEPES. Low‐potassium solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 11 glucose and 10 HEPES. High‐potassium solution contained 30 mM KCl (26.4 mM NaCl of the low‐potassium solution was replaced with KCl). The pH of the solutions was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Experiments were performed at room temperature (21°C). Data were analysed by pCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices).

Statistics and calculations

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). Results are expressed as means ± SEM. The number of oocytes measured in each group is given in the text and also in the figures. Normalized concentration–response curves were fitted with the following modified Hill equation: α × c nH/[c nH + K 1/2 nH] + 1, where c is the concentration, K 1/2 is the concentration at which half‐maximal stimulation occurs, n H is the Hill coefficient and α is the effect of the treatment. Statistical significance was determined by using the Mann–Whitney U‐test for independent samples or Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple groups followed by multiple comparisons of mean ranks for all groups. Results were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05. Curve fitting was done using SigmaPlot10 (Build 10.0.0.54; Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Statistical calculations were done using Statistica (version 13.2; Dell Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Materials

Chemicals of analytical grade were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), Fluka (Milwaukee, WI, USA) and Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). Enzymes and kits for molecular biology were purchased from Ambion, Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA) or Stratagene. Cloxyquin was purchased from Sigma, dissolved in ethanol and stored as 100 mM stock solution at −20°C. Ionomycin (calcium salt) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmington, NY, USA), dissolved in DMSO as a 5 mM stock solution and stored at −20°C. Benzocaine was purchased from Sigma, dissolved in ethanol and stored as a 30 mg·mL−1 solution.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (Alexander et al., 2015a,b).

Results

Cloxyquin is a specific activator of the TRESK channel

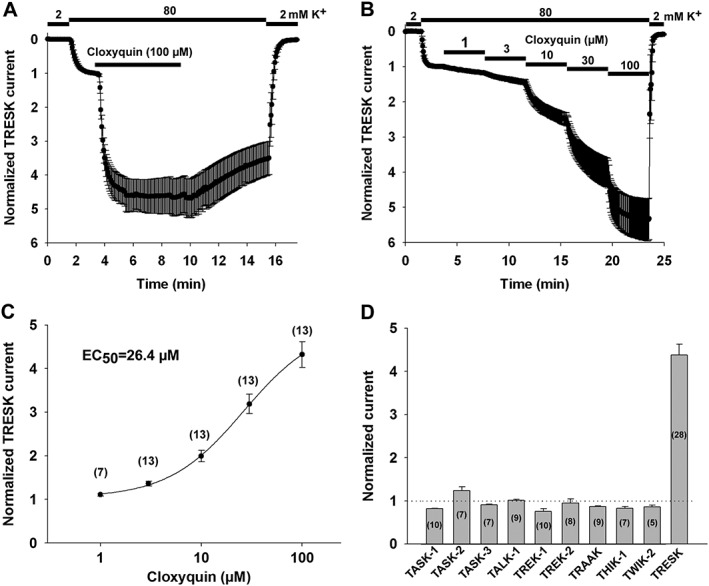

The mTRESK channel was expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Background potassium currents were estimated at −100 mV in 80 mM K+ after subtraction of the non‐specific leak current measured in 2 mM K+. Application of 100 μM cloxyquin strongly activated mTRESK currents (4.4 ± 0.3‐fold, n = 28 oocytes; the data plotted are from a representative experiment, n = 5 oocytes, Figure 1A). We also analysed the concentration–response relationship of mTRESK activation by cloxyquin (representative recording: Figure 1B, data shown are from n = 3 oocytes). Cloxyquin‐mediated activation of mTRESK was concentration dependent, with a half‐maximal effective concentration of 26.4 μM (Figure 1C). The effect of cloxyquin was slowly reversible (after 15 min of washout, return of TRESK current from the stimulated value was 56.7 ± 4.7%, n = 5).

Figure 1.

mTRESK is activated by cloxyquin. (A) Normalized currents of oocytes expressing mTRESK. The inward currents were measured at the end of 300 ms voltage steps to −100 mV applied every 4 s from a holding potential of 0 mV. Extracellular K+ was increased from 2 to 80 mM according to the bars above the graphs. Oocytes were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM) as indicated by the horizontal bar. Currents were normalized to the value measured in 80 mM K+ before cloxyquin application. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). (B) Concentration–response recording of mTRESK. Experimental conditions were the same as in panel (A). Increasing concentrations of cloxyquin were applied consecutively to oocytes expressing mTRESK. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Concentration–response relationship of cloxyquin and mTRESK current. The stimulatory effects of different concentrations of cloxyquin (in a range from 1 to 100 μM) on TRESK current are plotted. Each data point represents the average of 7 to 13 oocytes (the exact number is stated in parentheses). The data points were fitted with a modified Hill equation (for details, see the Methods section). (D) Cloxyquin selectively activates mTRESK. Mouse K2P channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The effect of cloxyquin on the inward current in 80 mM (or 40 mM in the case of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK) extracellular K+ [for experimental details, see panel (A)] was determined in 5–28 oocytes per channel type (the exact numbers are shown in the columns). Mean ± SEM of the normalized data points were plotted as a column graph (for time courses, see Supporting Information Figure S1). The dotted horizontal line indicates the normalized current before cloxyquin application.

Cloxyquin was previously described to have no effect on renal outer medullary K+ channel and hERG channels (Wright et al., 2013). To determine the specificity of the effect of cloxyquin within the K2P subfamily, we expressed the mouse orthologs of the following K2P channels in Xenopus oocytes: TWIK‐2 (K2P6.1), TASK‐1 (K2P3.1), TASK‐2 (K2P5.1), TASK‐3 (K2P9.1), TALK‐1 (K2P16.1), TREK‐1 (K2P2.1), TREK‐2 (K2P10.1), TRAAK (K2P4.1), THIK‐1 (K2P13.1) and TRESK. The effect of 100 μM cloxyquin was determined by using the two‐electrode voltage clamp. Among the K2P channels examined, only TRESK was robustly activated by cloxyquin. In the case of TASK‐2, there was a moderate (1.24 ± 0.09‐fold, n = 7) increase in the current upon application of cloxyquin. All other K2P channels were either unaffected or slightly inhibited by the compound (Figure 1D and Supporting Information Figure S1).

TRESK activation by cloxyquin depends on the functional state of the channel

In the above experiments, cloxyquin activated mTRESK channel more efficiently than described in a previous report (in which TRESK current was increased by about twofold in U20S cells) (Wright et al., 2013). Considering that TRESK is activated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ (via calcineurin‐mediated dephosphorylation), we hypothesized that the phosphorylation state of the channel may influence the effect of the drug. To test this possibility, we examined the effect of 100 μM cloxyquin on TRESK after pharmacological manipulation of the calcineurin‐mediated activation of the channel and also on different TRESK mutants with impaired Ca2+‐dependent regulation.

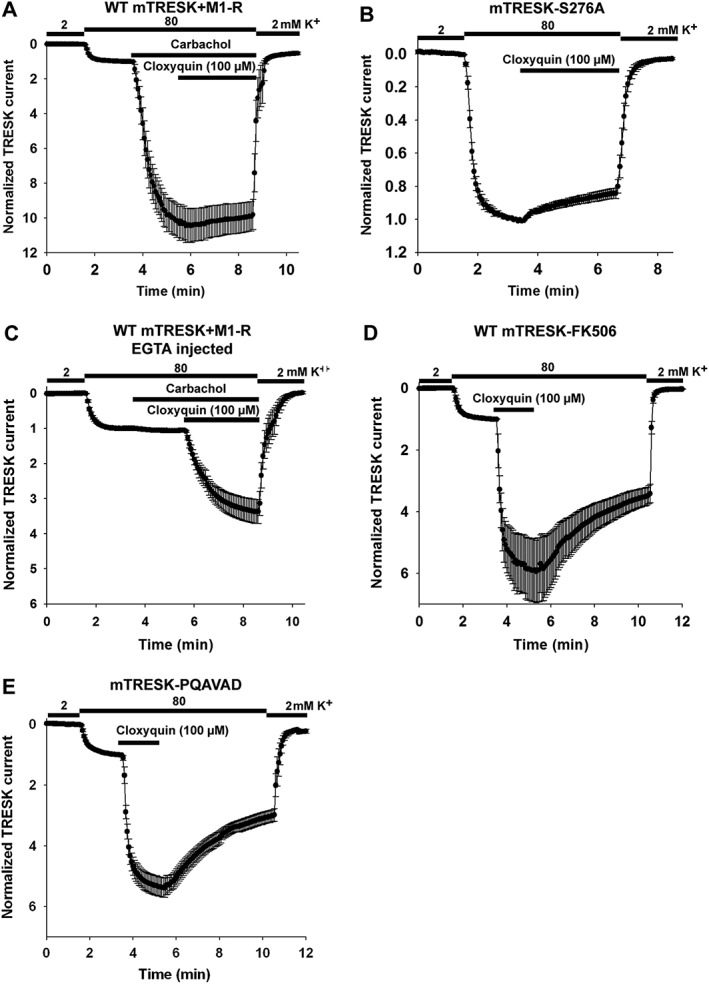

If mTRESK channels and M1 receptors were coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes; then stimulation with carbachol resulted in a substantial activation of mTRESK current (10.4 ± 1.0‐fold, n = 9 oocytes, Figure 2A). Subsequent application of cloxyquin failed to exert any additional effect on mTRESK current, suggesting that the receptor stimulation brings the channels in a conformation which cannot be further activated by cloxyquin. For this result to be confirmed, the effect of cloxyquin was also examined on a previously described constitutively active mutant, mTRESK S276A. Serine 276 is a major target of calcineurin; the alanine mutant mimicks the dephosporylated (i.e. activated) channel, which cannot be further activated by the calcium signal. In accordance with the results of M1 receptor stimulation, this mutant channel was not activated by cloxyquin. In fact, a small inhibition was observed (14.9 ± 3.0% inhibition, n = 11, Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The effect of cloxyquin is not mediated by calcium and calcineurin. Wild‐type or mutant mTRESK channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. In panels (A) and (C), the M1 receptor (M1‐R) was coexpressed with mTRESK. For experimental details and data presentation, see Figure 1A. (A) mTRESK current, after carbachol stimulation, cannot be further activated by cloxyquin. Oocytes coexpressing mTRESK and M1 receptors were challenged with carbachol (1 μM), followed by additional application of cloxyquin (100 μM) as indicated by the horizontal bars. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 9). (B) Cloxyquin does not influence the current of the constitutively active mTRESK S276A mutant channel. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (C) EGTA injection abolishes the M1 receptor‐ mediated activation of mTRESK but does not prevent the simulation by cloxyquin. Oocytes expressing mTRESK and M1 receptors were microinjected with EGTA 2 h before recording. The timings of extracellular K+ changes, carbachol (1 μM) and cloxyquin (100 μM) application are indicated by horizontal bars. Currents were normalized to the value measured in 80 mM K+ before carbachol application. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 10). (D) Inhibition of calcineurin does not prevent the activation of TRESK current induced by cloxyquin. Oocytes expressing mTRESK were pretreated with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (200 nM, 2–3.5 h before the recording). Oocytes expressing mTRESK were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 6). (E) The effect of cloxyquin is preserved in the mTRESK‐PQAVAD mutant in which the calcineurin‐binding site is disrupted. Oocytes expressing mTRESK‐PQAVAD mutant were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

A plausible explanation for the insensitivity of mTRESK to cloxyquin after calcium mobilizing receptor activation would be that the robust activation of the resting mTRESK current by the drug is also related to the Ca2+/calcineurin regulatory pathway. If this was the case, the effect of cloxyquin would be absolutely dependent on the elevation of cytoplasmic [Ca2+]. In order for this possibility to be examined, oocytes were injected with HEPES‐buffered EGTA (50 mM each) before recording. Stimulation with carbachol did not increase mTRESK current under this condition, indicating that the cytoplasmic [Ca2+] was efficiently buffered by EGTA. Subsequent application of cloxyquin activated the potassium current (3.3 ± 0.3‐fold, n = 12, Figure 2C). While EGTA injection appeared to slightly reduce the degree of activation, this effect was not statistically significant. The result clearly indicates that the channel activation by cloxyquin is not caused by the elevation of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ level.

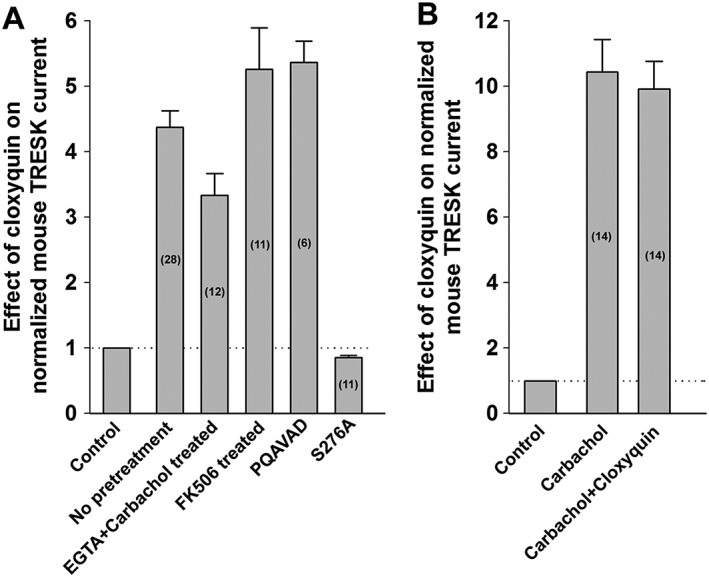

The increase of TRESK current might also be explained by the activation of calcineurin in response to cloxyquin application. However, if the oocytes were pretreated with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (200 nM, 2–3.5 h) before recording, then cloxyquin remained effective. It activated the channel 5.3 ± 0.7‐fold (representative recording is from n = 6 oocytes, Figure 2D), suggesting that the effect of cloxyquin is not mediated by calcineurin. This conclusion has also been confirmed by using a mutagenesis‐based approach. We have previously described a mutant channel which cannot bind calcineurin (in which the PQIVID calcineurin‐binding motif of TRESK is disrupted by PQAVAD mutation). Cloxyquin also activated this mutant (5.4 ± 0.3‐fold, n = 6, Figure 2E). We have summarized the effect of different experimental conditions on the efficacy of cloxyquin in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of the effects of different manipulations on the cloxyquin‐mediated mTRESK activation. (A) The effects of different manipulations on the cloxyquin‐mediated TRESK activation are summarized in a column graph. The number of oocytes recorded for each condition is shown in the columns. The first bar and the dotted horizontal line mark the normalized current before the application of cloxyquin. (B) The effect of carbachol (1 μM) and subsequent application of cloxyquin (100 μM) on mTRESK are summarized as a column graph. The number of oocytes recorded for each condition is shown in the columns. The first bar and the dotted horizontal line indicate the normalized current before carbachol application.

Cloxyquin activates hTRESK channel

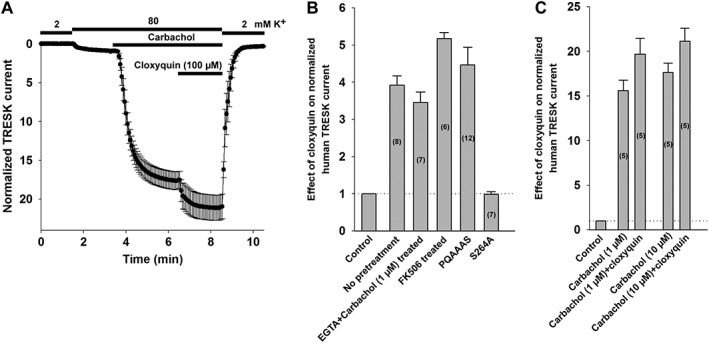

Differences in the regulation and pharmacological profile of human and mTRESK have been previously described (e.g. in addition to the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway, only the human orthologue is activated by PKC; the mouse orthologue is sensitive to Zn2+, while hTRESK is unaffected by the cation. For a review, see Enyedi and Czirják, 2015). Therefore, we probed the effect of cloxyquin on hTRESK using a similar approach as in the case of the mouse channel. We have summarized the results in Figure 4B, C (recordings are shown in Supporting Information Figure S2). Application of 100 μM cloxyquin activated the human channel 3.9 ± 0.3‐fold (n = 8). The activation was concentration‐dependent, with an EC50 of 43.9 μM (data are from n = 6 oocytes). In good accordance with our results on mTRESK, mutation of the major target serine of calcineurin (serine 264, which corresponds to S276 in the murine channel) to alanine abolished the effect of cloxyquin (2 ± 7% inhibition, n = 7). Cloxyquin also activated hTRESK if the oocytes were injected with EGTA before recording (3.4 ± 0.3‐fold, n = 7). Pretreatment with FK506 did not decrease the efficacy of cloxyquin (5.2 ± 0.2‐fold activation, n = 6). The stimulatory effect of cloxyquin was also maintained if the calcineurin‐binding site (PQIIIS) was disrupted by PQAAAS mutation (4.5 ± 0.5‐fold, n = 12). Unexpectedly, cloxyquin was able to slightly activate hTRESK current after carbachol stimulation (an additional 25 ± 0.03% increase, n = 5; compared with the stimulated value). To exclude the possibility that this was the consequence of submaximal activation of hTRESK by 1 μM carbachol, we stimulated the oocytes with higher concentration of the agonist (10 μM) before cloxyquin application. There was no difference in hTRESK activation by 1 or 10 μM carbachol (15.59 ± 1.17‐fold and 17.6 ± 1.03‐fold, respectively, n = 5–5). The cloxyquin‐mediated activation of hTRESK after the application of 10 μM carbachol was similar (1.20 ± 0.01‐fold, n = 5, Figure 4A) to the activation observed after stimulation with 1 μM carbachol. The effect of cloxyquin on hTRESK after stimulation by carbachol is summarized in Figure 4C.

Figure 4.

hTRESK is activated by cloxyquin. Wild‐type or mutant hTRESK channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. M1 receptors were coexpressed with hTRESK in the experiments where carbachol was applied. A similar experimental procedure was used as in Figure 2. (A) hTRESK channels and M1 receptors were coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes. Oocytes were stimulated with 10 μM carbachol to activate the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). (B) The degree of hTRESK activation by 100 μM cloxyquin under different circumstances is summarized as a column graph. The number of oocytes recorded for each condition is shown in the columns. The first bar and the dotted horizontal line indicate the normalized current before cloxyquin application. (C) The degree of hTRESK activation by 1 or 10 μM carbachol and subsequent application of 100 μM cloxyquin is summarized as a column graph. The number of oocytes recorded for each condition is shown in the columns. The first bar and the dotted horizontal line indicate the normalized current before carbachol application.

F156A, F364A pore mutant of mTRESK is constitutively active

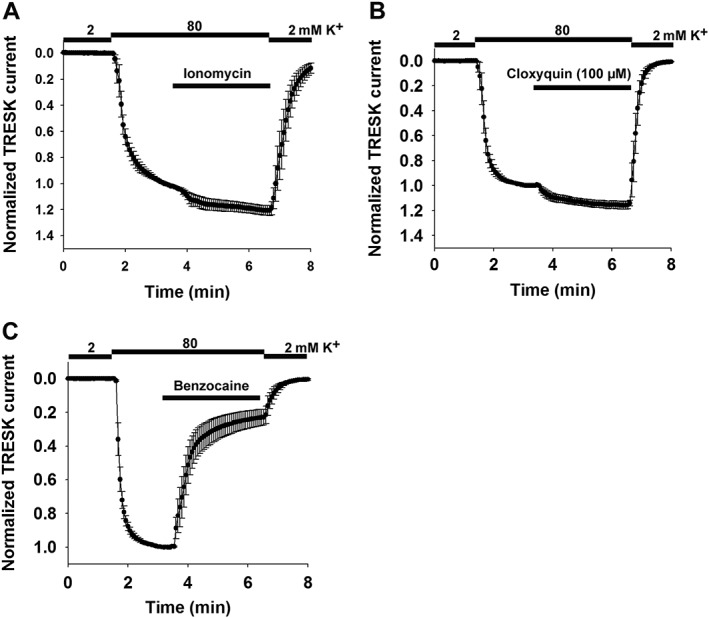

In a previous study (Kim et al., 2013), phenylalanine residues in the pore of mTRESK channel (F156, F364) were implicated in the binding of channel blockers quinine, lidocaine and bupivacaine (these compounds are non‐specific inhibitors of TRESK). Mutation of these residues to alanine abolished sensitivity to the channel blockers. We determined the effect of these mutations (using F156A, F364A double mutant mTRESK) on the pharmacological properties of the channel. The calcium ionophore ionomycin was previously shown to robustly activate the wild‐type channel via the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway (Czirják et al., 2004). The double mutant was almost completely resistant to the stimulatory effect of ionomycin (1.21 ± 0.04‐fold activation n = 5, Figure 5A), and cloxyquin also negligibly affected the mutant channel (1.14 ± 0.02‐fold, n = 5, Figure 5B). These results suggested that replacing the bulky hydrophobic/aromatic residues in the channel pore results in a channel that is in a more active state than wild‐type mTRESK. For this suggestion to be verified, equal amounts (0.4 ng) of wild‐type or F156A, F364A mutant mTRESK cRNA were injected into the oocytes. The current of the double mutant channel was significantly (five times) larger than that of the wild‐type mTRESK (3.2 ± 0.5 μA vs. 0.65 ± 0.1 μA, respectively, n = 6 oocytes in each group). The activated state of the mutant channel was also confirmed by application of 1 mM benzocaine. We have previously shown that TRESK, activated by Ca2+/calcineurin, is more sensitive to benzocaine than the channel in the resting state (Czirják and Enyedi, 2006a). As expected for an activated channel, the F156A, F364A mutant mTRESK was greatly inhibited by 1 mM benzocaine (77.1 ± 4.7% inhibition, n = 5, Figure 5C). The wild‐type mTRESK channel was not inhibited by benzocaine at all. However, the wild‐type mTRESK channel activated by cloxyquin was also sensitive to benzocaine (35.3 ± 2.1% inhibition, n = 7).

Figure 5.

The F156A, F364A mutant of TRESK is constitutively active. mTRESK F156A, F364A double mutant channel was expressed in Xenopus oocytes. For experimental details and data presentation, see Figure 1A. (A) Oocytes expressing the double mutant channel were challenged with the calcium ionophore ionomcyin (0.5 μM). (B) Cloxyquin (100 μM) was applied to oocytes expressing the double mutant channel. (C) Oocytes expressing the double mutant channel were challenged with benzocaine (1 mM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM, n = 5, in each experiment. Treatments are indicated as horizontal bars above the graphs.

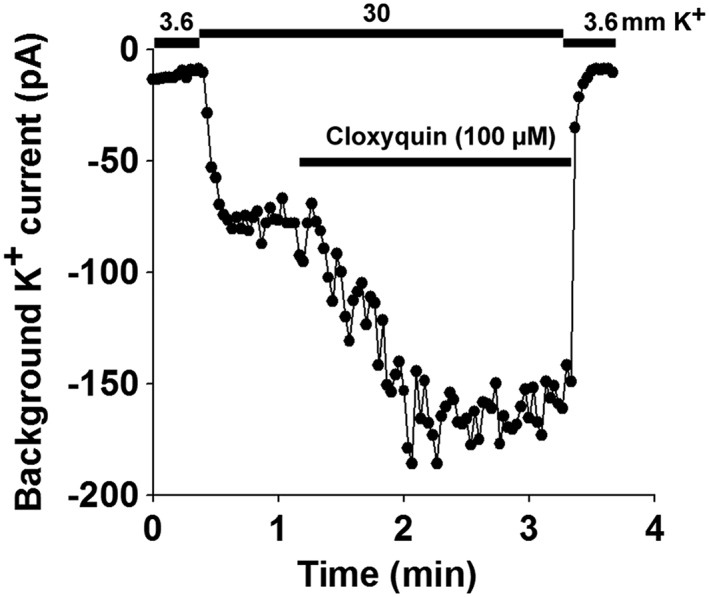

Cloxyquin activates the background potassium current in DRG neurons

TRESK is highly expressed in the primary somatosensory neurons of the DRGs. To test if cloxyquin can be used to identify TRESK current in native cells, we performed whole‐cell patch clamp recordings on isolated mouse DRG neurons. To ensure that TRESK channels had not been activated via the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway before patch clamp recording, we pretreated the DRG neurons overnight with the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine A (1 μM). We examined the effect of cloxyquin on DRG neurons. Cells not exhibiting voltage‐gated sodium or calcium currents (determined by applying a depolarizing ramp protocol to the cells) were excluded from the analysis. Twenty DRG neurons were analysed. The background potassium current of eight neurons was activated by the application of 100 μM cloxyquin. In these cells, application of cloxyquin increased the background potassium current by 41.1 ± 9.7% (for representative recording, see Figure 6), indicating that TRESK substantially contributes to the background potassium conductance in a subset of somatosensory neurons.

Figure 6.

Cloxyquin activates the background potassium current in DRG neurons. A representative recording is shown from a DRG neuron that responded to cloxyquin application. Inward currents were measured in 3.6 or 30 mM extracellular K+ at the end of 200 ms voltage steps to −100 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Changes in extracellular K+ and application of 100 μM cloxyquin are shown by the horizontal lines above the graph.

Discussion

K2P channels are expressed in a wide variety of cell types. These channels are the major determinants of the resting membrane potential and play an important role in the regulation of cellular excitability. K2P channels have been implicated in several physiological and pathological processes (for a review, see Enyedi and Czirják, 2010).

Pharmacological identification of K2P channels is a challenging task. Only a few relatively specific modulators of K2P channel activity have been described so far. Sanshool (Bautista et al., 2008), isobutylalkenyl amide (Tulleuda et al., 2011), lamotrigine (Kang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2013), aristolochic acid (Veale and Mathie, 2016), zinc and mercuric ions (Czirják and Enyedi, 2006b), capsaicin (Beltran et al., 2013), loratadine (Bruner et al., 2014), flufenamic acid (Monteillier et al., 2016) and other antidepressant or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (Park et al., 2016) have been well documented to modulate TRESK activity; however, they are also known to influence other pharmacological targets in addition to this K2P channel. A possible explanation for the lack of specific and high‐affinity pharmacological tools could be the extracellular cap domain found in the structure of K2P channels which prevents free access to the extracellular side of the pore domain (Brohawn et al., 2012; Miller and Long, 2012). The absence of specific TRESK modulators impedes the elucidation of the physiological function of the channel.

In a recent high‐throughput study, cloxyquin has been identified as an activator of TRESK (Wright et al., 2013). Cloxyquin belongs to the 8‐hydroxyquinoline family of drugs, which were used as antiprotozoal, antifungal and antibacterial agents in the past (Gholz and Arons, 1964). Cloxyquin was also reported to have anti‐mycobacterial activity (Hongmanee et al., 2007). It has recently been proposed that cloxyquin is also a mitochondrial uncoupler and cardioprotective compound (Zhang et al., 2016). The characteristic antimicrobial effects are believed to arise because of the metal chelating property of these compounds and the consequent interference with the metal‐binding sites on microbial enzymes (Gholz and Arons, 1964; Oliveri and Vecchio, 2016). Nevertheless, it appears unlikely that this chelating effect would contribute to the action of cloxyquin on TRESK, regarding the controlled ion concentrations in the extracellular space and the independence of the cloxyquin effect from the intracellular injection of the strong chelator EGTA in our experiments. In the present study, we have confirmed the effect of cloxyquin on TRESK background potassium channel and demonstrated the specificity of the compound in the K2P subfamily.

mTRESK is activated by cloxyquin

In the first experiments, we measured the effect of cloxyquin on mTRESK expressed in Xenopus oocytes. We found that the cloxyquin‐mediated activation of TRESK was concentration‐dependent, with an EC50 of 26.4 μM. This value is higher than the EC50 of 3.2 μM determined by patch clamp experiments in the case of TRESK expressed heterologously in U20S cells (Wright et al., 2013). Application of 100 μM cloxyquin resulted in a 4.4‐fold activation of TRESK current in Xenopus oocytes, in contrast to the previous report where the current amplitude was increased only twofold by the same concentration of the drug. Since TRESK is physiologically activated by Ca2+/calmodulin via calcineurin‐mediated dephosphorylation, it is plausible that the differences in the Ca2+/calcineurin signalling pathway are responsible for the variable degree of activation in response to cloxyquin in the different heterologous expression systems. This assumption seems to be especially feasible if we consider the interdependence of the calcineurin‐ and cloxyquin‐dependent activation mechanisms of TRESK, which was unequivocally demonstrated by our experiments.

We examined the relationship between the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway and the cloxyquin‐mediated TRESK activation using a variety of pharmacological tools and previously described TRESK mutants. When mTRESK was converted to the activated state by stimulation of the Gq‐protein coupled M1 muscarinic receptor, cloxyquin was unable to further activate the channel. Similar results were obtained with a mutant (S276A) mimicking the active, dephosphorylated form of the channel. Despite the clear interdependence of the cloxyquin effect with the activation by calcineurin, we have demonstrated that cloxyquin does not activate the channel by increasing the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. In oocytes microinjected with EGTA, carbachol stimulation had no effect, proving that the cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal was abolished by the chelator. Under these conditions, when the cytoplasmic [Ca2+] was buffered to subphysiological levels, cloxyquin was still able to activate TRESK current about 3.3‐fold. This activation is less than under control conditions (4.4‐fold); however, the difference was not statistically significant. This indicates that cytoplasmic [Ca2+] changes do not mediate the cloxyquin effect. The role of calcineurin as the mediator of cloxyquin effect was examined by using a pharmacological inhibitor of the phosphatase (FK506) and also by disrupting the PQIVID calcineurin‐binding site of the channel which was previously shown to be indispensable for dephosphorylation. While these manipulations abolish the Ca2+/calcineurin‐mediated activation of the channel (Czirják et al., 2004; Czirják and Enyedi, 2006a), they failed to influence the effect of cloxyquin, indicating that the phosphatase does not play a role in the effect of the drug. Our results suggest that cloxyquin is a direct modulator of TRESK.

Cloxyquin can activate hTRESK even after carbachol stimulation

hTRESK channels are also activated by the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway; however, there are some differences in their pharmacology compared with the mouse ortholog (for a review, see Enyedi and Czirják, 2015). Cloxyquin also activated hTRESK. The mechanism of action was similar as observed in the case of the mouse channel with one exception. Mouse channels activated by the Ca2+/calcineurin pathway were not stimulated further by cloxyquin. In contrast, cloxyquin was able to stimulate hTRESK by about 20% further after carbachol stimulation. This small additional effect was still apparent when the M1 receptor‐expressing oocytes were challenged by a higher concentration of carbachol, indicating that cloxyquin can increase hTRESK current even after maximal receptor‐mediated stimulation.

The F156A, F364A double mutant mTRESK is constitutively active

A previous computational study has identified phenylalanine residues (F156 and F364) in the pore of TRESK as potential binding sites for non‐specific blockers of the channel (bupivacaine, lidocaine and quinine) (Kim et al., 2013). We have determined the physiological regulation and pharmacological properties of the F156A, F364A double mutant channel. The failure of both ionomycin and cloxyquin to stimulate the mutant channel raised the possibility that these mutations lead to a constitutively active channel. To test this hypothesis, we injected oocytes with equal amounts of wild‐type or double mutant mTRESK cRNA. The current of the mutant channel was significantly larger (by fivefold) than that of the wild‐type channel, suggesting that this mutant is indeed in the activated state. We also determined the benzocaine sensitivity of the mutant channel. Benzocaine has been shown to differentiate between the resting state and the active state of TRESK; the local anaesthetic is a more potent inhibitor of the active channel (Czirják and Enyedi, 2006a). In this study, we have shown that benzocaine was able to inhibit the wild‐type channel activated by cloxyquin. Benzocaine efficiently inhibited the F156A, F364A double mutant channel, further supporting the conclusion that this channel is in the active state.

Cloxyquin is a selective for TRESK in the K2P family

We have demonstrated that cloxyquin is an efficient activator of TRESK and that this effect is more pronounced on channels in the resting state. In the original study, cloxyquin was shown to have no effect on an inwardly rectifying (Kir1.1) channel and a voltage‐gated (hERG) channel. However, the specificity was not examined in the K2P subfamily. If the effect of cloxyquin was not specific to TRESK and cloxyquin could also activate other K2P channels, the compound would be of limited use in identifying TRESK currents in native cells. Therefore, we examined the effect of cloxyquin on a broad range of widely expressed K2P channels. Only TRESK was significantly activated by the compound. Based on the data obtained in Xenopus oocytes, we propose that cloxyquin can be used to identify TRESK currents in native cells.

TRESK current can be identified in native cells using cloxyquin

Whole‐cell patch clamp measurements were performed on isolated mouse DRG neurons in order to demonstrate the contribution of TRESK to the background potassium current by the application of cloxyquin. The background potassium current was activated in a subpopulation (8 out of 20 cells). DRG neurons represent a heterogenic group of cells tuned to detect various, specific stimuli, and this heterogeneity may explain that cloxyquin did not activate the background potassium current uniformly in all the neurons examined. The degree of the cloxyquin‐mediated activation was smaller than that measured in the pure heterologous expression system. This may be because in contrast with the oocytes, DRG neurons express a variety of K2P channels. It is also possible that non‐specific phosphatases are activated during patch clamp recording conditions, leading to dephosphorylation and partial activation of TRESK, thus decreasing the amplitude of further stimulation by cloxyquin. Based on the data, cloxyquin can be used as a tool to identify TRESK functionally in native cells. It is an intriguing possibility to combine cloxyquin with other pharmacological tools (i.e. modulators of other ion channels) to identify which subset of DRG neurons express TRESK. However, these experiments are beyond the scope of the present study.

Further implications, potential clinical relevance

TRESK has been implicated in the pathophysiology of nociceptive disorders (e.g. migraine; Lafreniere et al., 2010; Mathie and Veale, 2015). Therefore, selective activators of TRESK could also be of therapeutic interest. The pharmaceutical industry has taken an interest in TRESK as a drug target (Bruner et al., 2014). In a recent report (Monteillier et al., 2016), the prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor flufenamic acid was reported to activate TRESK, but this drug also acts on several other K2P channels. Still, its derivatives were further examined; some of them proved to be slightly more potent, while others were inhibitors of TRESK. A major advantage of cloxyquin is its remarkable specificity (among K2P channels). However, regarding the relatively high concentration of cloxyquin required for TRESK activation, it remains an open question whether this drug can be used as a parent compound for developing clinically relevant high‐affinity TRESK modulators.

Author contributions

All authors conceived, designed and performed the experiments; analysed the data and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Effect of cloxyquin on other mouse K2P channels. Normalized currents of oocytes expressing different mouse K2P channel subunits. The inward currents were measured at the end of 300‐ms voltage steps to −100 mV applied every 4 s from a holding potential of 0 mV. Extracellular K+ was increased from 2 to 80 mM (or 40 mM in the case of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK) according to the bars above the graphs. Oocytes were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM) as indicated by the horizontal bar. Currents were normalized to the value measured in 80 mM K+ before cloxyquin application. Data are from 4–10 oocytes and plotted as mean ± SEM.

Figure S2 The effect of cloxyquin on human TRESK is not mediated by calcium and calcineurin. Wild type (panels A‐D) or the mutant (PQAAAS, panel E) human TRESK channels (hTRESK) were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. On panels B and C, M1 muscarinic receptor was coexpressed with hTRESK. Currents were measured by two‐electrode voltage clamp and the effect of 100 μM cloxyquin was determined. Data are plotted as in Figure 1. A, Representative recordings of the effect of cloxyquin on hTRESK. 100 μM cloxyquin was applied to oocytes expressing hTRESK (data are plotted as mean ± SEM, n = 5). B, Cloxyquin (100 μM) was able to further stimulate hTRESK channel even after their stimulation by1 μM carbachol. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). C. Oocytes expressing hTRESK and M1 muscarinic receptor were microinjected with EGTA before recording. EGTA prevented the activation of TRESK by 1 μM carbachol, but cloxyquin (100 μM) was able to stimulate the channel. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7). D, Oocytes expressing hTRESK were pretreated with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (200 nM, 2–3.5 h before the recording). Oocytes were challenged with 100 μM cloxyquin following this pretreatment. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). E, Oocytes expressing hTRESK PQAAAS mutant were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7). F, Oocytes expressing hTRESK S264A mutant were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hungarian National Research Fund (OTKA K108496). Valuable discussions with Professor András Spät are highly appreciated. The skilful technical assistance of Irén Veres is acknowledged.

Lengyel, M. , Dobolyi, A. , Czirják, G. , and Enyedi, P. (2017) Selective and state‐dependent activation of TRESK (K2P18.1) background potassium channel by cloxyquin. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174: 2102–2113. doi: 10.1111/bph.13821.

References

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Catterall WA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5904–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Sigal YM, Milstein AD, Garrison JL, Zorn JA, Tsuruda PR et al. (2008). Pungent agents from Szechuan peppers excite sensory neurons by inhibiting two‐pore potassium channels. Nat Neurosci 11: 772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran LR, Dawid C, Beltran M, Gisselmann G, Degenhardt K, Mathie K et al. (2013). The pungent substances piperine, capsaicin, 6‐gingerol and polygodial inhibit the human two‐pore domain potassium channels TASK‐1, TASK‐3 and TRESK. Front Pharmacol 4: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun G, Lengyel M, Enyedi P, Czirják G (2015). Differential sensitivity of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK background potassium channels to the polycationic dye ruthenium red. Br J Pharmacol 172: 1728–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun G, Nemcsics B, Enyedi P, Czirják G (2011). TRESK background K(+) channel is inhibited by PAR‐1/MARK microtubule affinity‐regulating kinases in Xenopus oocytes. PLoS One 6: e28119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn SG, del Marmol J, MacKinnon R (2012). Crystal structure of the human K2P TRAAK, a lipid‐ and mechano‐sensitive K+ ion channel. Science 335: 436–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JK, Zou B, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Schmidt K, Li M (2014). Identification of novel small molecule modulators of K2P18.1 two‐pore potassium channel. Eur J Pharmacol 740: 603–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P (2002). Formation of functional heterodimers between the TASK‐1 and TASK‐3 two‐pore domain potassium channel subunits. J Biol Chem 277: 5426–5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P (2006a). Targeting of calcineurin to an NFAT‐like docking site is required for the calcium‐dependent activation of the background K+ channel, TRESK. J Biol Chem 281: 14677–14682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P (2006b). Zinc and mercuric ions distinguish TRESK from the other two‐pore‐domain K+ channels. Mol Pharmacol 69: 1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P (2010). TRESK background K(+) channel is inhibited by phosphorylation via two distinct pathways. J Biol Chem 285: 14549–14557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Enyedi P (2014). The LQLP calcineurin docking site is a major determinant of the calcium‐dependent activation of human TRESK background K+ channel. J Biol Chem 289: 29506–29518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czirják G, Tóth ZE, Enyedi P (2004). The two‐pore domain K+ channel, TRESK, is activated by the cytoplasmic calcium signal through calcineurin. J Biol Chem 279: 18550–18558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi P, Czirják G (2010). Molecular background of leak K+ currents: two‐pore domain potassium channels. Physiol Rev 90: 559–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi P, Czirják G (2015). Properties, regulation, pharmacology, and functions of the K(2)p channel, TRESK. Pflugers Arch 467: 945–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholz LM, Arons WL (1964). Prophylaxis and therapy of amebiasis and shigellosis with iodochlorhydroxyquin. Am J Trop Med Hyg 13: 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongmanee P, Rukseree K, Buabut B, Somsri B, Palittapongarnpim P (2007). In vitro activities of cloxyquin (5‐chloroquinolin‐8‐ol) against Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51: 1105–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Kim D (2006). TREK‐2 (K2P10.1) and TRESK (K2P18.1) are major background K+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C138–C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Kim GT, Kim EJ, La JH, Lee JS, Lee ES et al. (2008). Lamotrigine inhibits TRESK regulated by G‐protein coupled receptor agonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 367: 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee Y, Tak HM, Park HJ, Sohn YS, Hwang S et al. (2013). Identification of blocker binding site in mouse TRESK by molecular modeling and mutational studies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828: 1131–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafreniere RG, Cader MZ, Poulin JF, Andres‐Enguix I, Simoneau M, Gupta N et al. (2010). A dominant‐negative mutation in the TRESK potassium channel is linked to familial migraine with aura. Nat Med 16: 1157–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel M, Czirják G, Enyedi P (2016). Formation of functional heterodimers by TREK‐1 and TREK‐2 two‐pore domain potassium channel subunits. J Biol Chem 291: 13649–13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Xiao Z, Ren F, Guo Z, Chen Z, Zhao H et al. (2013). Functional analysis of a migraine‐associated TRESK K+ channel mutation. J Neurosci 33: 12810–12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Veale EL (2015). Two‐pore domain potassium channels: potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of pain. Pflugers Arch 467: 931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AN, Long SB (2012). Crystal structure of the human two‐pore domain potassium channel K2P1. Science 335: 432–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteillier A, Loucif A, Omoto K, Stevens EB, Vicente SL, Saintot P‐P et al. (2016). Investigation of the structure activity relationship of flufenamic acid derivatives at the human TRESK channel K2P18.1. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 26: 4919–4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri V, Vecchio G (2016). 8‐Hydroxyquinolines in medicinal chemistry: a structural perspective. Eur J Med Chem 120: 252–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Kim E‐J, Han J, Han J, Kang D (2016). Effects of analgesics and antidepressants on TREK‐2 and TRESK currents. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 20: 379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y, Inamura K, Miyake A, Mochizuki S, Kitada C, Yokoi H et al. (2003). A novel two‐pore domain K+ channel, TRESK, is localized in the spinal cord. J Biol Chem 278: 27406–27412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulleuda A, Cokic B, Callejo G, Saiani B, Serra J, Gasull X (2011). TRESK channel contribution to nociceptive sensory neurons excitability: modulation by nerve injury. Mol Pain 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale EL, Mathie A (2016). Aristolochic acid, a plant extract used in the treatment of pain and linked to Balkan endemic nephropathy, is a regulator of K2P channels. Br J Pharmacol 173: 1639–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PD, Weir G, Cartland J, Tickle D, Kettleborough C, Cader MZ et al. (2013). Cloxyquin (5‐chloroquinolin‐8‐ol) is an activator of the two‐pore domain potassium channel TRESK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 441: 463–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Hatakeyama T, Taniguchi K (2009). Immunohistochemical colocalization of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK with TRP channels in the trigeminal ganglion cells. Neurosci Lett 454: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S, Liu J, Sabbadini M, Au P, Xie GX, Yost CS (2009). Regional expression of the anesthetic‐activated potassium channel TRESK in the rat nervous system. Neurosci Lett 465: 79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nadtochiy SM, Urciuoli WR, Brookes PS (2016). The cardioprotective compound cloxyquin uncouples mitochondria and induces autophagy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H29–H38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Effect of cloxyquin on other mouse K2P channels. Normalized currents of oocytes expressing different mouse K2P channel subunits. The inward currents were measured at the end of 300‐ms voltage steps to −100 mV applied every 4 s from a holding potential of 0 mV. Extracellular K+ was increased from 2 to 80 mM (or 40 mM in the case of TREK‐1, TREK‐2 and TRAAK) according to the bars above the graphs. Oocytes were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM) as indicated by the horizontal bar. Currents were normalized to the value measured in 80 mM K+ before cloxyquin application. Data are from 4–10 oocytes and plotted as mean ± SEM.

Figure S2 The effect of cloxyquin on human TRESK is not mediated by calcium and calcineurin. Wild type (panels A‐D) or the mutant (PQAAAS, panel E) human TRESK channels (hTRESK) were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. On panels B and C, M1 muscarinic receptor was coexpressed with hTRESK. Currents were measured by two‐electrode voltage clamp and the effect of 100 μM cloxyquin was determined. Data are plotted as in Figure 1. A, Representative recordings of the effect of cloxyquin on hTRESK. 100 μM cloxyquin was applied to oocytes expressing hTRESK (data are plotted as mean ± SEM, n = 5). B, Cloxyquin (100 μM) was able to further stimulate hTRESK channel even after their stimulation by1 μM carbachol. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). C. Oocytes expressing hTRESK and M1 muscarinic receptor were microinjected with EGTA before recording. EGTA prevented the activation of TRESK by 1 μM carbachol, but cloxyquin (100 μM) was able to stimulate the channel. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7). D, Oocytes expressing hTRESK were pretreated with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (200 nM, 2–3.5 h before the recording). Oocytes were challenged with 100 μM cloxyquin following this pretreatment. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 5). E, Oocytes expressing hTRESK PQAAAS mutant were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7). F, Oocytes expressing hTRESK S264A mutant were challenged with cloxyquin (100 μM). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 7).