Highlights

-

•

Open pelvic fractures can present unique and difficult clinical problems.

-

•

The pelvic ring is a dynamic structure in normal physiologic conditions.

-

•

Suture and anchor fixation can be used as definitive fixation of the pelvic ring.

Keywords: Open pelvis fracture, Pediatric pelvis fracture, Dynamic fixation, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Pelvic fractures are relatively uncommon in children, accounting for 0.3–7.5% of all pediatric injuries (Gänsslen et al., 2013; Ismail et al., 1996; Peltier, 1965; Galano et al., 2005; Spiguel et al., 2006). This case report describes a pediatric open pelvic injury caused by a crush mechanism between a car and guardrail.

Case

A 13 year old male presented with an open APC 3 pelvic injury after being pinned between a car and guardrail. His definitive treatment included bilateral SI screw placement, as well as a less invasive method for anterior pelvic ring disruption (Internal Brace suture anchor dynamic fixation).

Discussion/conclusion

A less invasive method for the anterior pelvic ring was used to avoid additional dissection due to extensive soft tissue loss, and to decrease hardware burden, which lessens the chance of complications such as infection. Suture fixation of the pubic symphysis provided stable fixation to allow healing in the current case of open pelvic fracture.

1. Introduction

Pelvic fractures are relatively uncommon in children, accounting for 0.3–7.5% of all pediatric injuries [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Open book pelvic fractures in children are rare. In a series of 166 patients, Silber et al. reported one open book injury (0.6%) [6]. According to the review of literature by Gänsslen A, the reported mortality rate averages 6.4% [1]. This case report describes a pediatric open pelvic injury caused by a crush mechanism between a car and guardrail, and has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [7].

2. Case

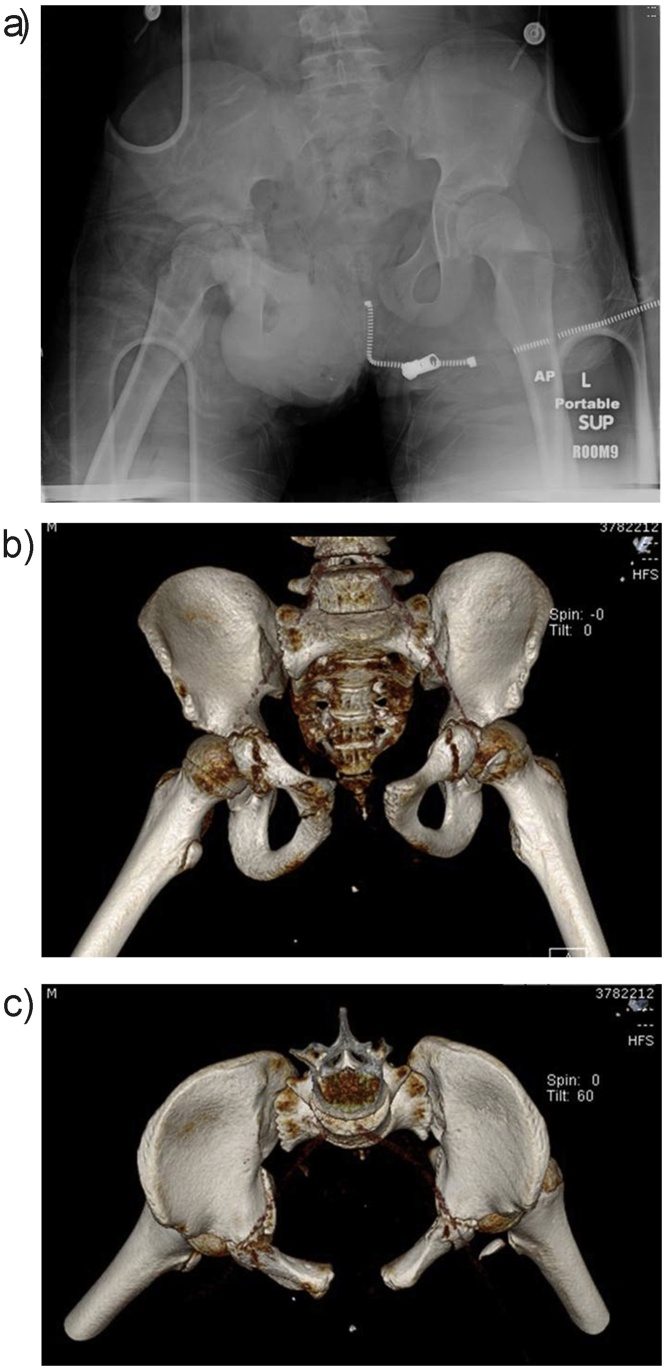

A 13 year old male was pinned between a car and a guardrail on the shoulder of a highway after a collision with another vehicle. He was brought into the Emergency Department by ambulance. On initial evaluation, he had open bilateral groin wounds (6 × 20 cm in each groin) extending posteriorly to the rectum. Upon radiographic evaluation he was found to have an Anterior Posterior Compression (APC) pelvic injury. Pelvic Computed Tomography (CT) scan was obtained to better visualize and classify the injury, showing an APC3 type injury (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Injury Films A) AP Pelvis showing APC type injury radiograph B) 3-D CT reconstruction of pelvis.

He was taken to interventional radiology for embolization. He was then transported promptly from the Radiology suite to the Operating Room where a suprapubic catheter was placed, a diverting colostomy was performed, and the pelvis was packed (due to continued bleeding). Pelvic external fixation was performed in order to provide mechanical stabilization.

The patient was hemodynamically stabilized and on post injury day 2, he returned to the OR for percutaneous bilateral sacroiliac reduction and screw placement. During the ensuing 2 weeks, he underwent multiple anterior pelvic debridements and received IV antibiotics. Meanwhile, his pelvic external fixator remained in place as temporary fixation of the anterior pelvic ring.

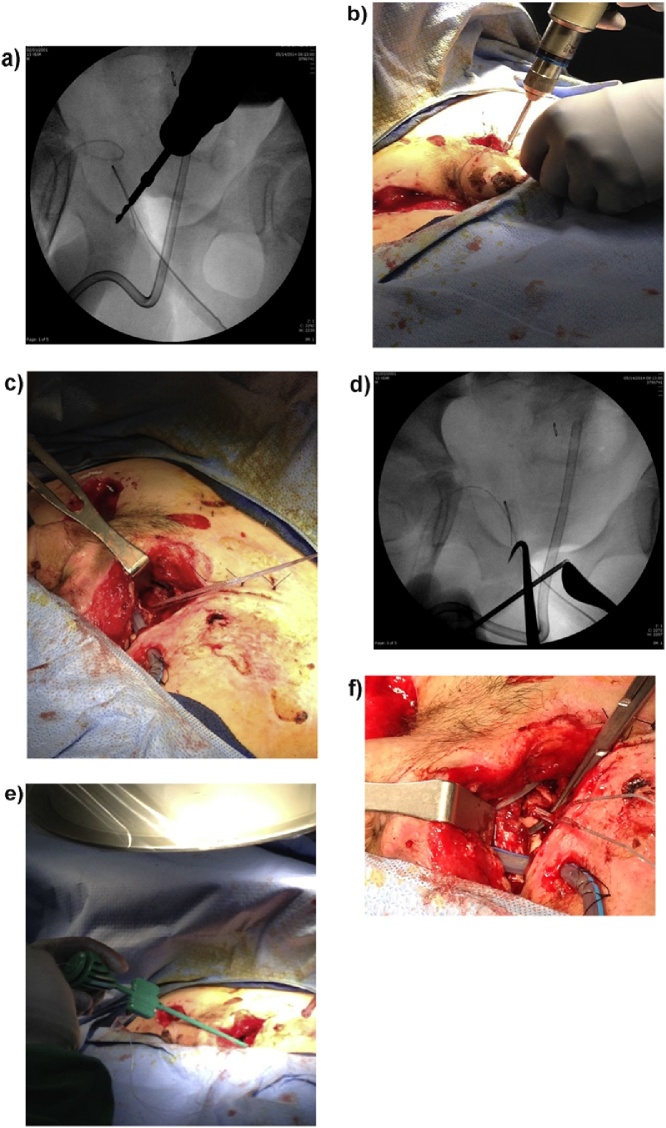

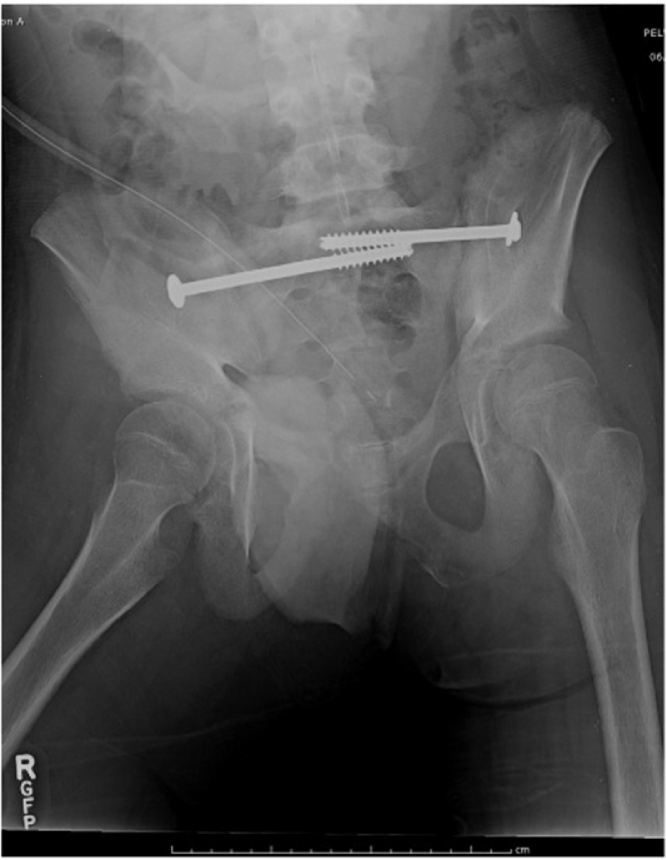

Due to the open wounds and concomitant injuries, definitive pelvic surgery on the anterior ring included suture and anchor fixation (Internal Brace) of the pubic symphysis, performed to provide secure fixation anteriorly while avoiding hardware burden and additional dissection. Surgery was performed by the senior author (JTR) at two weeks post injury. Access to the pubic symphysis was attained via the open left groin wound. A drill was used to penetrate the right ramus. A 4.75 mm anchor was used after tapping to hold 2 limbs of fiber tape. A reduction maneuver was then performed with a bone hook around the right superior ramus, and a picador on the left superior ramus. The left superior ramus was then drilled, and a second anchor was placed after tapping to securely hold the 2 limbs of fiber tape in order to secure the reduction (Fig. 2). The external fixator was left in place initially in the event that any problem arose with the definitive anterior fixation, but was superfluous at that point. Two weeks post internal fixation, the external fixator was removed. Post removal, EUA confirmed a stable pelvis, without any movement of the symphysis. The remainder of his hospitalization was uneventful. At 6 weeks the patient was released for full weight bearing (Fig. 3). His pelvis remained stable, without any signs of lost fixation. At last contact with the patient at 2 years from his injury he reported no pain or problems related to his pelvic injury. The traumatic pelvic wounds healed uneventfully. He had no activity restrictions, bears full weight without any assistive device, and was able to participate in all desired activities including skateboarding daily.

Fig. 2.

A) Intraoperative radiograph showing drilling of the right superior rami for 4.75 mm Arthrex suture anchor B) Intraoperative drilling right superior rami through open left groin wound C) Post suture anchor placement into the right superior rami with fiber tape shown exiting the open left groin wound D) Intraoperative radiograph showing 4.75 mm suture anchor placement into the left superior rami E) Placement of 4.75 mm Suture anchor in to the left superior rami F) Anchors and suture in place.

Fig. 3.

6 week post-operative AP pelvis radiograph showing stable pelvis.

3. Discussion

Pelvic fractures are relatively uncommon in children, 0.3–7.5% of all pediatric injuries, but when they occur it is typically due to high-energy impact to the lower torso in association with blunt trauma [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Gansslen reviewed the literature on pediatric pelvis fractures, which showed that children with pelvic injuries have an average of 5.2 concomitant injuries [1]. A multisystem approach to investigation and treatment is essential, because concomitant injury to other organ systems determines overall mortality in this patient group [8]. Open pelvic fractures have been reported to occur at a rate of 0.6–12.9% of all pediatric pelvic fractures, and mortality rate in these cases can be as high as 20% [1], [6].

Nabaweesi retrospectively, through the pediatric trauma registry of Maryland, looked at all blunt trauma patients younger than 15 years of age, with a final diagnosis of pelvic fracture as the primary outcome of interest. Associations with pediatric pelvic fractures included being male, Caucasian, age between 5 and 14 years, being struck as a pedestrian, or motor vehicle accident occupant. These identifying factors can be used to aid clinicians in selecting patients who may benefit from pelvic radiography. Males were 40% more likely than females to have a pelvic fracture. Children aged 5–9 and 10–14 were three times and five times more likely to present with a pelvic fracture as compared to children aged 4 years and younger. African-Americans were 40% less likely to sustain a pelvic fracture than Caucasians. Compared to falls, individuals being struck as a pedestrian or being an occupant in a motor vehicle crash were six times and 2 times respectively more likely to have a pelvic fracture [9].

Pelvic fracture patterns in children typically differ from those seen in adults; this is due to a flexible bony matrix, strong ligamentous complexes, and physeal lines of weakness. Because of a more ductile pelvis, a higher magnitude of force is needed to produce a pediatric pelvic fracture [8]. The fragile points of the pediatric pelvis are the triradiate cartilage and the sacroiliac joint. Quick classified pelvic fractures into three groups: those not requiring laparotomy, those requiring laparotomy for visceral injury, and those where the fracture was associated with severe vascular injury [10]. This classification avoids any consideration of distinct fracture patterns and takes into account the direct relationship between pelvic injury and severity of the overall traumatic insult. The Torode and Zieg classification system is another commonly used classification that describes pediatric pelvic fractures.

High rates of morbidity exist in children that survive displaced pelvic injuries, with over 30% having residual pain, limp, scoliosis, or back pain [11]. This is thought to be due to either malreduction or incomplete reduction of sacroiliac disruption, which may lead to premature sacroiliac joint fusion, severe pelvic obliquity, scoliosis, or ilium undergrowth. For this reason Oransky et al. published a case series where unstable/displaced pediatric pelvic fractures were surgically treated. In their opinion, non-anatomic reduction will lead to serious problems in adulthood. The pelvic ring will grow in the position left after trauma; residual displacement will not correct spontaneously. Even with proper reduction and fixation, damage or arrest of growth centers will lead to undergrowth [11]. Smith et al. concluded that fractures associated with greater than or equal to 1.1 cm of pelvic asymmetry following closed reduction should be treated with some form of operative fixation [12]. For displaced fractures of the pelvic ring, operative reduction and internal fixation have become the standard of care.

Currently there is dispute about adapting adult principles to pediatric patients. The question of, “at what age should a pediatric pelvic fracture be considered for adult management” has yet to be determined. Banjeree observed that within the pediatric age group, those above thirteen years old are more prone to unstable fractures, concluding that pediatric pelvic fractures reach an adult nature around 13 years of age [13].

4. Conclusion

In our case of a 13 year old male with an unstable pelvic ring injury, the decision to use a less invasive method for the anterior pelvic ring was made to 1) avoid additional dissection in the setting of a severely damaged soft tissue envelope, and 2) to decrease hardware burden, which lessens the chance of complications such as infection. Dynamic suture fixation of the pubic symphysis provided stable fixation and allowed healing in the current case of open pelvic fracture.

Conflicts of interest

John Riehl: Consultant and Royalties Arthrex.

Funding

No sources of funding were received for this case report.

Ethical approval

An IRB waiver was given as this is a case report. Consent was given by the patient’s father to publish this case report.

Consent

As the patient is a minor, consent was given by the patient’s parent.

Author contributions

Study concept and design, surgery, writing: John Riehl.

Writing: Brian Dilworth.

Guarantor

John Riehl, employee of Coastal Orthopaedic Trauma, LLC.

Contributor Information

Brian R. Dilworth, Email: Bdilworth5@gmail.com.

John T. Riehl, Email: jtriehl@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Gänsslen A., Heidari N., Weinberg A.M. Fractures of the pelvis in children: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2013;23(December (8)):847–861. doi: 10.1007/s00590-012-1102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ismail N., Bellemare J.F., Mollitt D.L. Death from pelvic fracture: children are different. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1996;31(1):82–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peltier L.F. Complications associated with fractures of the pelvis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1965;47:1060–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galano G.J., Vitale M.A., Kessler M.W., Hyman J.E., Vitale M.G. The most frequent traumatic orthopaedic injuries from a national pediatric inpatient population. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2005;25:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiguel L., Glynn L., Liu D., Statter M. Pediatric pelvic fractures: a marker for injury severity. Am. Surg. 2006;72:481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silber J.S., Flynn J.M., Koffler K.M. Analysis of the cause, classification, and associated injuries of 166 consecutive pediatric pelvic fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2001;21(4):446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holden C.P., Holman J., Herman M.J. Pediatric pelvic fractures. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007;15(March (3)):172–177. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nabaweesi R., Arnold M.A., Chang D.C. Prehospital predictors of risk for pelvic fractures in pediatric trauma patients. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2008;24(September (9)):1053–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quick T.J., Eastwood D.M. Pediatric fractures and dislocations of the hip and pelvis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005;432(March):87–96. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000155372.65446.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oransky M., Arduini M., Tortora M., Zoppi A.R. Surgical treatment of unstable pelvic fracture in children: long term results. Injury. 2010;41(November (11)):1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith W., Shurnas P., Morgan S. Clinical outcomes of unstable pelvic fractures in skeletally immature patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005;87(November (11)):2423–2431. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01244v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee S., Barry M.J., Paterson J.M. Paediatric pelvic fractures: 10 years experience in a trauma centre. Injury. 2009;40(April (4)):410–413. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]