Abstract

Prenatal exposure to a maternal low protein diet has been known to cause cognitive impairment, learning and memory deficits. However, the underlying mechanisms have not been identified. Herein, we demonstrate that a maternal low protein (LP) diet causes, in the brains of the neonatal rat offspring, an attenuation in the basal expression of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a neurotrophin indispensable for learning and memory. Female rats were fed either a 20% normal protein diet (NP) or an 8% low protein (LP) three weeks before breeding and during the gestation period. Maternal LP diet caused a significant reduction in the Bdnf expression in the brains of the neonatal rats. We further found that the maternal LP diet reduced the activation of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway. This reduction was associated with a significant decrease in CREB binding to the Bdnf promoters. We also show that prenatal exposure to the maternal LP diet results in an inactive or repressed exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brain, as evidenced by fluxes in signatory hallmarks in the enrichment of acetylated and trimethylated histones in the nucleosomes that envelop the exon I and exon IV promoters, causing the Bdnf gene to be refractory to transactivation. Our study is the first to determine the impact of a maternal LP diet on the basal expression of BDNF in the brains of the neonatal rats exposed prenatally to a LP diet.

Keywords: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, cAMP response element binding protein, histone acetylation, histone methylation, maternal low protein diet

1. Introduction

Prenatal exposure to a maternal low protein (LP) diet has been known to result in reduced birth weights, shorter life-span, developmental abnormalities leading to cardiac and reproductive dysfunction, fluxes in systemic and brain metabolism, and perinatal epigenetic alterations leading to cognitive impairment in the neonatal offspring [1]. Maternal LP diets also cause defects in the noradrenaline neurotransmitter network in the neocortex in the brain, deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP), and impairments in visual and spatial memory, in the neonatal offspring [2, 3]. Prenatal protein restriction has been shown to evoke indelible long-term deleterious changes in the brain such as transformations in neurogenesis, cell migration and differentiation, defects in neuronal circuits, and axonal and dendritic pruning accompanied by augmented neuronal death [3]. Additionally, maternal LP diets cause profound changes in the hippocampal formation region of the brain of the neonatal offspring leading to behavioral abnormalities, impairments in cognitive function, as well as deficits in learning and memory [3–6]. Profound structural, functional, and metabolic changes in the brains of the neonatal offspring [7] characterized by impaired cerebral vascularization [8], cerebral hypometabolism [9], reduced number of dendritic spines [7] have all been found in the neonatal offspring rats exposed prenatally to maternal LP diet. The mechanisms by which maternal LP diets induce the aforementioned deleterious changes in the brain are poorly understood, but derangements in the expression and physiological function of growth factors may be involved [1, 10–12]. Neurotrophins, such as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), are growth factors endogenously expressed in the brain that play a pivotal role in neurogenesis [13, 14], neuronal survival [15], synaptogenesis [16], synaptic plasticity [17], and neuronal energy metabolism [18–20]. BDNF is the most abundant growth factor in brain [21, 22] and its expression is tightly regulated by the transcription factor cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) [23], which is activated by the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) /Protein Kinase A (PKA) pathway [24]. The cAMP/PKA/CREB — BDNF pathway has been shown to be critically involved in the regulation of neurogenesis, neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, as well as neuronal energy metabolism [25].

There is evidence that prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet results in fluxes in the cAMP levels [26] and PKA expression [27] in the neonatal offspring. However, there are no studies to-date that have determined the effect of a maternal LP diet on the expression of BDNF in the neonatal progeny. In this study we determined the impact of maternal LP diet on the cAMP levels and the activation status of PKA in the brains of the neonatal offspring. We further determined the impact of the maternal LP diet on the expression and activation of CREB, the downstream effector of the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway, and subsequently determined the effects of maternal LP diet on CREB-mediated BDNF expression in the brains of the neonatal offspring. We demonstrate that maternal LP diet reduces cAMP levels as well as PKA enzymatic activity in the whole brains of the neonatal offspring, leading to an attenuation in the CREB-mediated expression of BDNF. We further show that maternal LP diet evokes a reduction in the acetylation of known Histone H3 and Histone H4 residues concomitant with fluxes in the methylation status of key Histone H3 and Histone H4 residues in the exon I and exon IV promoters of the Bdnf gene that result in a repressed chromatin that is refractory to CREB-mediated transactivation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Sprague-Dawley female rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were fed an AIN93-based diet containing either 8% (low protein, LP) or 20% protein (normal protein, NP) isocaloric diet starting 3 weeks prior to breeding. The respective male breeders were maintained on a normal chow diet. Dams were maintained on their respective diets throughout pregnancy. The composition of the respective diets [10] is shown in Table 1. The diets were formulated and analyzed for total protein quantity and the uniformity in the composition of amino acids to ensure that the effects of the maternal LP diet were attributable to the reduction in the whole volume of proteins and not due to a depletion of certain key amino acids. Special emphasis and attention was given to ensure uniform levels of the methyl donor amino acid, L-cystine, that has been shown to be important in epigenetic pathway regulations. The amino acid composition of the casein in the respective diets is shown in Table 2. Food intake was not altered between the group of dams that were fed a normal protein (NP) diet versus the group of dams that were fed a low protein (LP) diet. The birth weights of male neonates born of dams fed LP diet were lower than that of male neonates born of dams fed NP diet as we previously reported [28]. No significant differences in body weight, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue weights were observed between the group of dams that were fed a NP diet versus the group of dams that were fed a low protein diet during 3 weeks each of preconception, gestation, and lactation periods [29]. Neonatal pups (0–1 days old) were sacrificed by carbon dioxide inhalation and their brains harvested. Harvested whole brain tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. All animal experiments comply with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). All animal procedures were according to animal use and care protocol approved by the USDA ARS Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Table 1.

Composition of the normal protein (NP) diet and low protein (LP) diet

| Constituent | Normal protein (NP) diet 20% protein w/w | Low protein (LP) diet 8% protein w/w |

|---|---|---|

| Casein, g (kcal) | 200 (800) | 80 (320) |

| L-cysteine, g (kcal) | 3 (12) | 3 (12) |

| Corn starch, g (kcal) | 310 (1240) | 390.82 (1563.3) |

| Maltodextrin, g (kcal) | 35 (140) | 35 (140) |

| Sucrose, g (kcal) | 297.5 (1190) | 337.91 (1351.6) |

| Cellulose, g | 50 | 50 |

| Soybean oil, g (kcal) | 25 (225) | 25 (225) |

| Lard, g (kcal) | 20 (180) | 20 (180) |

| Calcium carbonate, g | 12.5 | 7.27 |

| Calcium hydrogen phosphate, g | 4 | 4 |

| Mineral mix, g | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin mix, g | 10 (40) | 10 (40) |

| Choline bitartarate, g | 2 | 2 |

| Total, g (kcal) | 1000 (3827) | 1000 (3832) |

| Protein, % weight (% kcal) | 20.3 (21.22) | 8.3 (8.66) |

| Carbohydrate, % weight (% kcal) | 67.24 (67.26) | 79.36 (79.83) |

| Total Fat, % weight (% kcal) | 4.5 (10.58) | 4.5 (10.57) |

Table 2.

Amino acid composition of casein (percent of amino acid present in casein)

| Amino acid | % of casein | Relative amount per kg diet Normal protein (NP) diet g / kg | Relative amount per kg diet Low protein (NP) diet g / kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 2.7 | 5.40 | 2.16 |

| Arginine | 3.3 | 6.60 | 2.64 |

| Aspartic acid | 6.1 | 12.20 | 4.88 |

| Cystine | 0.3 | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| Glutamic acid | 19.6 | 39.20 | 15.68 |

| Glycine | 1.6 | 3.20 | 1.28 |

| Histidine | 2.5 | 5.00 | 2.00 |

| Isoleucine | 5.0 | 10.00 | 4.00 |

| Leucine | 8.0 | 16.00 | 6.40 |

| Lysine | 7.0 | 14.00 | 5.60 |

| Methionine | 2.3 | 4.60 | 1.84 |

| Phenylalanine | 4.4 | 8.80 | 3.52 |

| Proline | 9.2 | 18.40 | 7.36 |

| Serine | 4.8 | 9.60 | 3.84 |

| Threonine | 3.8 | 7.60 | 3.04 |

| Tryptophan | 1.0 | 2.00 | 0.80 |

| Tyrosine | 4.6 | 9.20 | 3.68 |

| Valine | 6.0 | 12.00 | 4.80 |

2.2 Western Blot analysis

Whole cell, cytosolic and nuclear homogenates from rat whole brain tissue were prepared as previously described [30–35] and as follows. For preparing whole cell homogenates from rat brain tissues, 40–60mg of the rat whole brain tissue was dounce homogenized in RIPA tissue lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cytosolic and nuclear fractions from the rat whole brain tissues were prepared by sequential cellular fractionation [36, 37]. Briefly, rat whole brain tissue was homogenized in a hypotonic buffer (10mM HEPES, 1.5mM Mgcl2, 10mM KCl, 0.5mM DTT, pH 7.4) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min to pellet the nuclear fraction and collect the supernatant as the cytosolic lysate. The nuclear pellet was subjected to sucrose gradient separation. The pelleted nuclei were re-suspended in 3mL of 0.25M sucrose buffer (0.25M sucrose, 10mM Mgcl2) banking (layered upon) on 3mL of 0.35M sucrose buffer (0.25M sucrose, 10mM Mgcl2). The lysate was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min to pellet the nuclei and the pelleted nuclei were re-suspended in 3mL 0.35M sucrose buffer followed by sonication (6 pulses of 8 sec with 10 second intervals) and the lysate containing the sheared nuclei were banked on (layered upon) on 3mL of 0.88M sucrose buffer. The samples were centrifuged 5000 × g for 10 min and the supernatant harvested as the nuclear extract. To prepare the lysates for western blotting analysis, 5× RIPA lysis buffer was added to the fractionated cytosolic and nuclear homogenates. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford protein assay method. Proteins (10–50μg) were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and incubation with the monoclonal antibodies listed in Table 3. The origin, source, the dilutions of the respective antibodies used for this study is compiled in Table 3. β-actin was used as a gel loading control for whole cell and cytosolic homogenates, whereas Histone H3 was used as a gel loading control for nuclear homogenates. The blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Clarity™ Western ECL blotting substrate, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and imaged using a LICOR Odyssey Fc imaging system.

Table 3.

List of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies used in the study

| Antibody | Dilution | Amount | Host | Manufacturer | Catalog # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | 1:500 | 10 μg | rabbit | Thermo Fisher | OSB00017W |

| pro-BDNF | 1:300 | 16 μg | rabbit | Sigma Aldrich | P1374 |

| β-Actin | 1:2500 | 2 μg | mouse | Santa Cruz | sc-47778 (C4) |

| CBP | 1:500 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 7389(D6C5) |

| p-Ser133 CREB | 1:200 | 25 μg | mouse | Cell Signaling | 9196(1B6) |

| CREB | 1:500 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 9197(48H2) |

| CRTC2 | 1:400 | 12.5 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 3826 |

| Acetyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 9649 |

| Acetyl-Lys14 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 7627 |

| Acetyl-Lys18 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 13998 |

| Acetyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 8173 |

| Acetyl-Lys5 Histone H4 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 8647 |

| Acetyl-Lys8 Histone H4 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 2594 |

| Acetyl-Lys12 Histone H4 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 13944 |

| trimethyl-Lys4 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 9751 |

| trimethyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 13969 |

| trimethyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 9733 |

| trimethyl-Lys36 Histone H3 | 1:100 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 4909 |

| Histone H3 | 1:1000 | 5 μg | rabbit | Santa Cruz | sc-8654 (C16) |

| p300 | 1:250 | 20 μg | mouse | Active Motif | 61401 |

| p-Thr197 PKA-Cα | 1:200 | 25 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 4781 |

| PKA-Cα | 1:500 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | 5842(D38C6) |

| p-Ser338 PKA-Cβ | 1:200 | 25 μg | rabbit | Thermo Fisher | PA1-26733 |

| PKA-Cβ | 1:500 | 10 μg | rabbit | Cell Signaling | PA5-13794 |

2.3 Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated and extracted from the rat whole brains by using the 5 prime “PerfectPure RNA tissue kit” (5 Prime, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) as previously described [38–40]. Real-time qRT-PCR analysis to quantify rat Bdnf mRNA transcripts containing exons I through IXa was performed using a one-step cDNA synthesis and amplification kit from ThermoFisher Scientific (Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit, Catalog# 4389986) following manufacturer’s instructions. The exon-specific primers are enumerated in Table 4. The amplification was performed using the “StepOnePlus” PCR System (ABI, Foster City, CA). The expression of specific transcripts amplified was normalized to the expression of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Hprt1). The data were quantified and expressed as fold-change compared to the control by using the ΔΔCT method.

Table 4.

List of primers used for qRT-PCR analysis

| Species | Gene | Gene ID | Exon | Primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Forward: 5′- GTGTGACCTGAGCAGTGGGCAAAGGA - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | 1I | Forward: 5′ - GGAAGTGGAAGAAACCGTCTAGAGCA - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | III | Forward: 5′- CCTTTCTATTTTCCCTCCCCGAGAGT - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Forward: 5′- CTCTGCCTAGATCAAATGGAGCTTC - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | V | Forward: 5′- CTCTGTGTAGTTTCATTGTGTGTTC - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | VI | Forward: 5′ - GCTGGCTGTCGCACGGTCCCCATT - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | VII | Forward: 5′ - CCTGAAAGGGTCTGCGGAACTCCA - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | VIII | Forward: 5′ - GTGTGTGTCTCTGCGCCTCAGTGGA - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IXa | Forward: 5′ - CCAGAGCTGCTAAAGTGGGAGGAAG - 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | Reverse | Reverse: 5′- GAAGTGTACAAGTCCGCGTCCTTA - 3′ |

| Rat | Hprt1 | 24465 | Forward | Forward: 5′ - GATGATGAACCAGGTTATGAC - 3′ |

| Rat | Hprt1 | 24465 | Reverse | Reverse: 5′- GTCCTTTTCACCAGCAAGCTTG- 3′ |

2.4 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the determination of total BDNF

Total BDNF levels (free and Trk-bound pro-BDNF as well as mature BDNF) was quantified using a sandwich ELISA kit (Total BDNF Quantikine ELISA Kit from R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, Catalog # DBNT00) following manufacturer’s instructions. The kit detects both, free and Trk-bound BDNF. The kit measures total BDNF levels that subsumes pro-BDNF and mature-BDNF levels. The total BDNF levels were measured in quadruplet (n=6, four technical replicates within each biological replicate). Total BDNF levels in the rat whole brain homogenates were normalized to total protein content in the samples. The data is expressed as mean ± SD and total BDNF levels are expressed as absolute levels (pg/mg of protein content).

2.5 Immunoprecipitation

Rat whole-brain tissues were homogenized using a non-denaturing lysis buffer (20mM Tris HCl, 137mM Nacl, 2mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease / phosphatase inhibitors and 100μM IBMX (Isobutylmehtylxanthine). The homogenate containing the equivalent to 750μg of total protein was pre-cleared by incubation with protein A/G coated agarose beads for 30 min at 4° C to reduce the non-specific binding of proteins to the beads. The equivalent of 750μg of the pre-cleared lysate was incubated separately with 5μg of anti PKA-Cα rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, Catalog # 5842) overnight at 4° C followed by capturing of the immune-complex by the addition of protein A/G agarose beads and incubation overnight. The beads containing the immune-complex were washed 3x with the lysis buffer followed by centrifugation and discarder of the supernatant. The beads were suspended in the lysis buffer and centrifuged to pellet the beads. The pellet (beads) containing the PKA-enriched fraction was subjected to PKA activity assay.

2.6 Measurement of intracellular cAMP levels

The intracellular levels of cAMP were determined by the ELISA method using a kit from Cell BioLabs (Catalog # STA-501) following manufacturer’s instructions and guidelines. Briefly, rat whole brain homogenates were fractionated into the cytosolic and membrane fractions [36, 37]. The homogenates were prepared in the propriety lysis buffer provided with the kit and contained 100μM IBMX to inhibit any residual phosphodiesterase activity. The lysates emanating from each of the respective fractions (equivalent to 10μg total protein content) was added concomitantly with the kit-provided peroxidase-conjugated cAMP tracer solution to each well of the 96-well ELISA plate coated with rabbit anti-cAMP polyclonal antibody. The cAMP present in the sample or standard competes with the peroxidase-conjugated cAMP tracer for binding to the rabbit anti-cAMP polyclonal antibody coated on each of the well plates. Following incubation and wash steps, any peroxidase-conjugated cAMP tracer bound to the plate is detected with the addition of chemiluminescence reagent. The light product formed is inversely proportional to the amount of the cAMP present in the sample. This light intensity was then measured by a plate luminometer. A standard curve was prepared from the cAMP standards and subsequently the cAMP levels in the samples was deduced from the standard curve.

2.7 Protein Kinase A (PKA) activity assay

The enzymatic activity of PKA was determined by the ELISA method using a kit from Abcam (ab139435) following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, whole brain homogenates were fractionated into the cytosolic, nuclear, and membrane fractions [36, 37]. The abundance of the catalytic subunit of PKA (PKA-C) was enriched in each of the fractions by immunoprecipitating PKA-C using a PKA-Cα specific monoclonal antibody and as described under the “Immunoprecipitation” section of this manuscript. The PKA-C enriched beads from immunoprecipitation were re-suspended in the kinase-assay buffer provided the kit. The PKA-C enriched lysates emanating from each of the respective fractions (equivalent to 2μg total protein content) was added to each well of the 96-well ELISA plate coated with the specific PKA substrate that can be phosphorylated and allowed to incubate at 30°C for two hours. The kinase activity was measured by the addition of a phospho-specific primary antibody directed against the phosphorylated PKA substrate and a secondary antibody conjugated to HRP added to provide a sensitive colorimetric readout at 450 nm.

2.8 CREB transcriptional activity assay

The transcriptional activity of activated CREB (p-Ser133 CREB) was determined by the ELISA method using a kit from Abcam (ab133117) following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, nuclear homogenate equivalent to 20μg of the protein content was added to each of the wells of the 96-well plate containing the double stranded DNA sequence harboring the consensus CREB binding sequence (CRE site) coated onto the wells. The nuclear extract was allowed to hybridize with the coated double stranded DNA sequence harboring the consensus CRE in the plate overnight at 4°C. The activated CREB transcription factor complex was detected by addition of a specific primary antibody directed against p-Ser133 CREB and a secondary antibody conjugated to HRP added to provide a sensitive colorimetric readout at 450 nm.

2.9 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Analysis

ChIP analysis was performed to evaluate the extent of CREB binding to the CRE elements as well as the extent of Histone H3 and Histone H4 modifications in the promoters of exon I and exon IV of the Bdnf gene, using “SimpleChIP™ Enzymatic Chromatic IP kit” from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA) following manufacturer’s instructions and as described earlier [30–33]. Briefly, rat whole brain tissue (~100mg) was taken and cross-linked with 37% formaldehyde for 15 min followed by the addition of 500μL of 1.25M glycine solution to cease the cross-linking reaction The tissue was washed with 4x volume of 1x PBS and centrifuged at ~220g for 5 min. The pellet was re-suspended and incubated for 10 min in 5 ml of tissue lysis buffer containing DTT, protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The pellet was dounce homogenized and sonicated to shear the DNA. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1000 × g and the pellet was re-suspended in a buffer containing DTT (provided with the kit). 5% of micrococcal nuclease (provided with the kit) was added to each tube to digest DNA to a length ranging approximately from 150–900 bp for 20 min at room temperature followed by stopping the digest by the addition of 100μL of 0.5M EDTA. The homogenates were now centrifuged at 15000g for 2 min and the pellet was re-suspended and incubated for 10 min in 1ml of ChIP buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The lysates were sonicated to disrupt the nuclear membrane and centrifuged at 15000g for 15 min. The cross-linked chromatin from each sample was apportioned into three equal parts. One third of the cross-linked chromatin was set aside as “input”. One third of the cross-linked chromatin from each sample was incubated with 5μg of the designated antibodies, while the remaining one third of the cross-linked chromatin from each sample was incubated with 5μg of normal mouse or rabbit IgG to serve as negative control. The cross-linked chromatin samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with their respective antibodies. The DNA-protein complexes were collected with Protein G agarose beads and washed to remove non-specific antibody binding. The DNA from the DNA-protein complexes from all the samples including the input and negative control was reverse cross-linked by incubation with 2μL of Proteinase K for 2 hours at 65°C. The crude DNA extract was eluted and then washed several times with wash buffer containing ethanol (provided with the kit) followed by purification with the use of DNA spin columns provided by the manufacturer. The pure DNA was eluted out of the DNA spin columns using 50μL of the DNA elution buffer provided in the kit. The DNA fragment size was determined by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel. The relative abundance of the designated antibody precipitated chromatin was determined by qPCR using sequence specific primers (Qiagen Inc. (Valencia, CA). The list of primers used for the ChIP analysis is presented in Table 5. The amplification was performed using the “StepOnePlus” PCR System (ABI, Foster City, CA). The fold enrichment of the bound CREB or histone modification in the Bdnf exon I promoter and exon IV promoter was calculated using the ΔΔCt method which normalizes ChIP Ct values of each sample to the % input and background.

Table 5.

List of primers used for ChIP analysis

| Species | Gene | Gene ID | Exon | ChIP | Primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | CREB | 5′- GCACGAACTTTTCTAAGAAGTTT - 3′ 5′- GGAACTTGTTGCTTTCCTG — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | CREB | 5′- TGCAGGGGAATTAGGGATACC— - 3′ 5′- TGAGCTTCGATTGGTCAGACA— 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys14 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys14 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys18 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys18 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys5 Histone H4 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys5 Histone H4 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys8 Histone H4 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys8 Histone H4 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | Acetyl-Lys12 Histone H4 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | Acetyl-Lys12 Histone H4 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | trimethyl-Lys4 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | trimethyl-Lys4 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | trimethyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | trimethyl-Lys9 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | trimethyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | trimethyl-Lys27 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | I | trimethyl-Lys36 Histone H3 | 5′- CCCCGCTGCGCTTTTCTGGT — 3′ 5′- CAATTTGCACGCCGCTCCTTTAC — 3′ |

| Rat | Bdnf | 24225 | IV | trimethyl-Lys36 Histone H3 | 5′-ATGCAATGCCCTGGAACGGAA-3′ 5′-TAGTGGAAATTGCATGGCGGAGGT-3′ |

2.10 Immunoblotting analysis of CBP, p300, and CRTC2 in the reverse cross-linked CREB-ChIP samples

Subsequent to the reverse cross-linking of the DNA-protein complexes and separation of the chromatin, the supernatant was subjected to western blotting analysis to determine the levels of the co-activator proteins CBP, p300, and CRTC2 associated with CREB.

2.11 Statistical analysis

The significance of differences among the samples was assessed by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 6. Quantitative data for all the assays are presented as mean values ± S.D (mean values ± standard deviation) with unit value assigned to control and the magnitude of differences among the samples being expressed relative to the unit value of control as fold-change.

3. Results

3.1 Maternal LP diet attenuates BDNF expression levels in the brains of the neonatal offspring

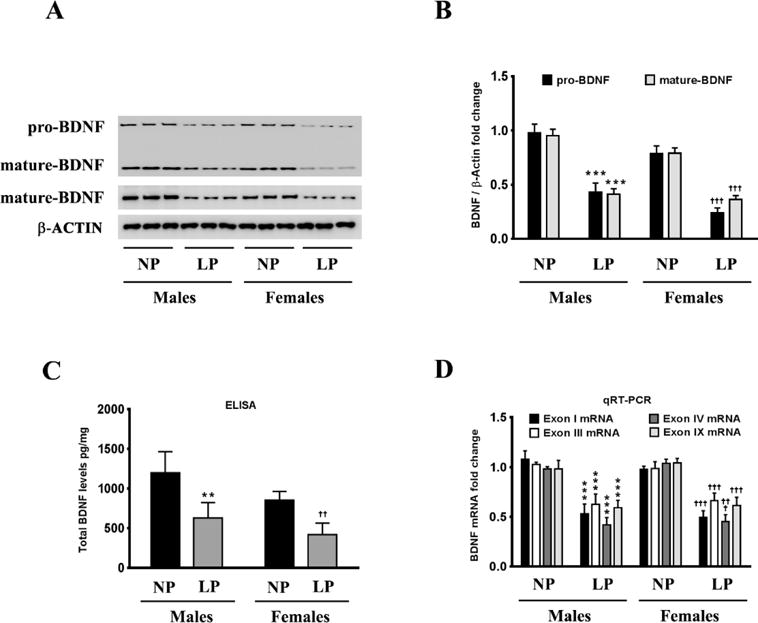

We first determined the effect of maternal LP diet on BDNF protein levels in the brains of the neonatal offspring. BDNF is synthesized as prepro-BDNF which is processed into pro-BDNF and further cleaved into mature-BDNF [41]. A consensus has emerged from recent studies ascribing distinct functions to pro-BDNF and mature BDNF with a certain degree of redundant physiological roles between the two proteins [21, 42–44]. We measured the protein levels of mature-BDNF as well as pro-BDNF in the whole brain homogenates of male and female neonatal pups prenatally exposed to LP diet or a NP diet. Western blotting and densitometry analysis shows that maternal LP diet significantly decreases the pro-BDNF and mature-BDNF levels by 56% and 59% respectively in the brains of the male neonatal offspring while reducing pro-BDNF and mature-BDNF levels by 71% and 53% respectively in the brains of the female neonatal offspring (Fig 1A, 1B). The determination of total BDNF (free and Trk-bound pro-BDNF as well as mature BDNF) protein levels in the whole brain homogenates by sandwich ELISA method concurred with the western blotting data, showing a decrease in total BDNF by 48% in male and 52% in female neonates prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet levels compared to the maternal NP diet (Fig 1C). The rodent BDNF gene has nine promoters with each promoter preceding an exon (exon I–IX) [45, 46]. Consequently, there are multiple transcription sites and alternate splicing results in the twenty-two known BDNF mRNA transcripts [45]. However, all the transcripts contain the exon IX that codes for the same protein [45]. We quantified BDNF mRNA transcripts containing different exons by using sequence-specific primers to each transcript. Prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet significantly decreased the expression of BDNF mRNA transcripts containing exons I, III, IV, and IX in the brains of the neonatal offspring (Fig 1D), while the expression of BDNF mRNA transcripts containing exons II, V, VI, VII, and VIII were not changed (data not shown), in the brains of the neonatal offspring.

Figure 1. Effects of maternal LP diet on Bdnf expression in the brains of the neonatal offspring rats.

(A, B) Representative western blots (A) and densitometric analysis (B) showing the effects of prenatal exposure to the maternal LP diet on the pro-BDNF and mature BDNF protein levels in the whole-brain homogenates of the neonatal offspring. (C) ELISA immunoassay showing the effects of a maternal LP diet on total BDNF protein levels (free and Trk-bound pro-BDNF as well as mature BDNF) in whole brain homogenates of the neonatal offspring. (D) Real-time RT-PCR analysis demonstrating the effects of prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet on the abundance of the BDNF mRNA transcripts containing exons I, III, IV, and IX. Data is expressed as Mean ± S.D and includes determination made in six (n=6) different animals from each group. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus male neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal normal protein (NP) diet; ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001 versus female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet.

3.2 Maternal LP diet decreases cAMP levels leading to a reduction in PKA activity

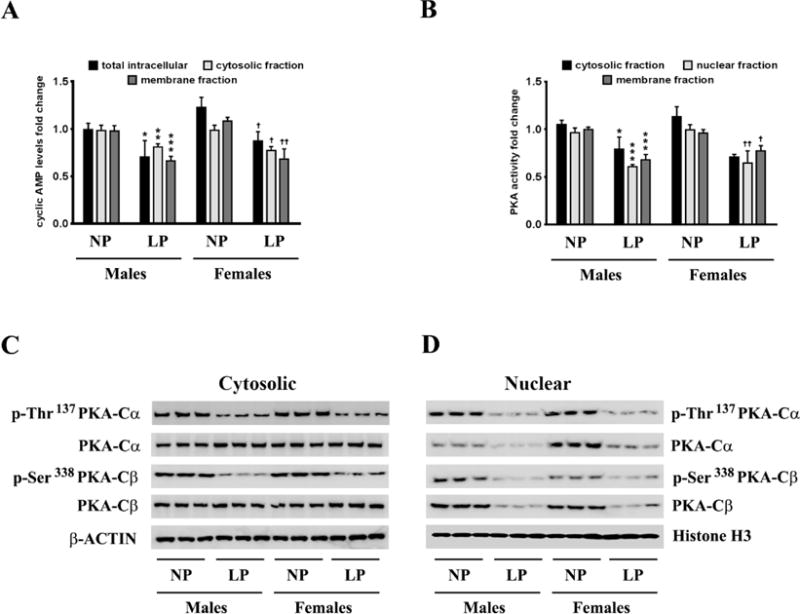

We delineated the molecular mechanism underlying the maternal LP diet-induced attenuation in BDNF expression in the brains of the neonatal offspring. The expression of BDNF is intricately regulated by the cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway [23, 24, 47–51]. We therefore determined whether each of the individual components of this signaling pathway was altered in the brains of the neonatal offspring rats exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet. Intracellular cAMP levels were significantly reduced by 30% and 28% in the brains of the male and female neonatal offspring respectively, exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 2A). As cAMP accumulation is compartmentalized into distinct, specific, restricted pools within the cell [52], we also measured fluxes in the cAMP levels in the cytosolic and the membrane fraction. The maternal LP diet reduced levels of cAMP by 18% and 22% in the cytosolic fraction isolated from the whole brain homogenates of the male and female neonatal offspring respectively (Fig 2A). The levels of cAMP in the membrane-fraction were also significantly reduced by 33% and 38% in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring respectively (Fig 2A). PKA is one of the prominent effector proteins mediating the effects of cAMP [53]. PKA exists as a heterotetramer consisting of a dimer of catalytic subunits (PKA-Cα, PKA-Cβ, or PKA-Cγ) and a dimer of regulatory subunits (PKA-RIα, PKA-RIβ, PKA-RIIα, or PKA-RIIβ) [54, 55]. The binding of cAMP to the two regulatory subunits results in the release of the catalytic dimer that exhibits kinase activity towards specific substrates including CREB [56]. We subsequently determined the activation status of PKA by measuring the kinase activity of PKA as well as the phosphorylation status of the catalytic subunits of PKA in the cytosolic and nuclear homogenates. PKA enzymatic activity was significantly reduced in the cytosolic and membrane fractions isolated from the whole brain homogenates from the neonatal offspring that were exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 2B). More importantly, PKA activity was significantly reduced in the nuclear homogenate fraction by 37% and 35% in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring respectively (Fig 2B). Furthermore, the reduction in PKA kinase activity correlated with decreased phosphorylation of the PKA-Cα subunit at the Thr197 residue and phosphorylation of the PKA-Cβ subunit at Ser338 (Fig 2C) followed by a commensurate reduction in their nuclear translocation (Fig 2D), both of which are essential for PKA kinase activity [57].

Figure 2. Effects of maternal LP diet on cAMP levels and PKA activity in the brains of the neonatal offspring.

(A) ELISA immunoassay demonstrating the effects of a maternal LP diet on cAMP levels in the whole cell, cytosolic, and membranes fractions from the whole brain homogenates of the neonatal offspring. (B) ELISA immunoassay showing the effects of prenatal exposure to a LP diet on PKA activity in the cytosolic, nuclear, and membranes fractions from the whole brain homogenates of the neonatal offspring. (C) Representative western blots showing the effects of maternal LP diet on the phosphorylation of the PKA catalytic subunits, PKA-Cα and PKA-Cβ, as well as the subsequent nuclear translocation of PKA-Cα and PKA-Cβ, in the brains of the neonatal offspring. Data is expressed as Mean ± S.D and includes determination made in six (n=6) different animals from each group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus male neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet; †p<0.05, ††p<0.01 versus female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet.

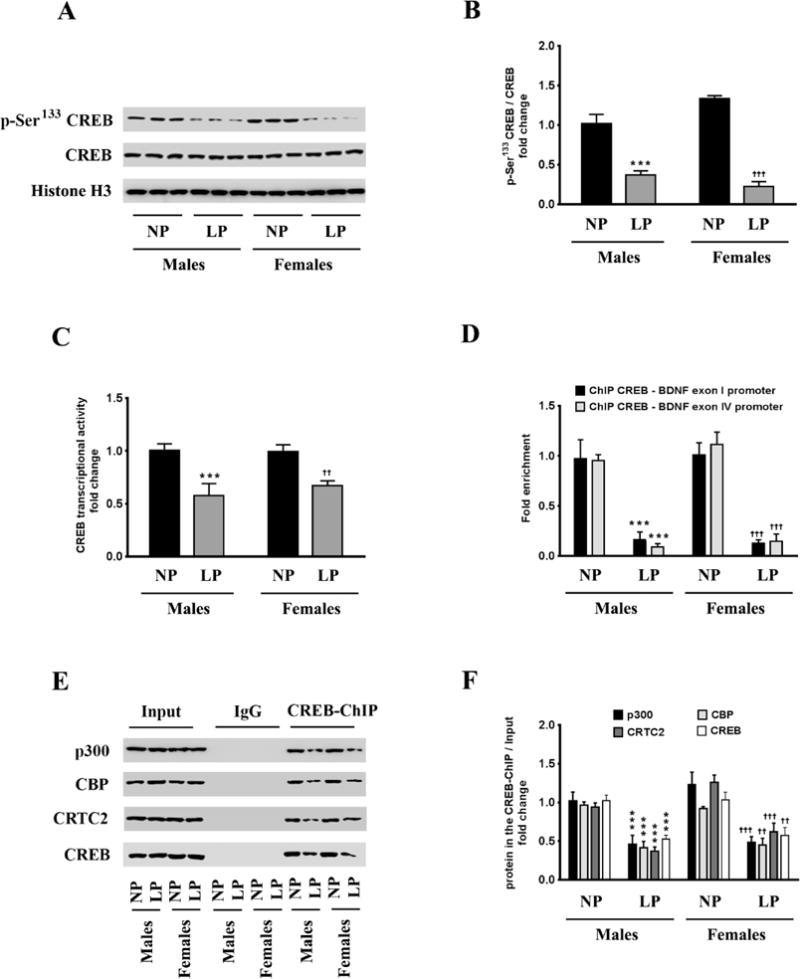

3.3 Maternal LP diet attenuates CREB activation and transcriptional activity resulting in a profound mitigation in the CREB-mediated BDNF expression

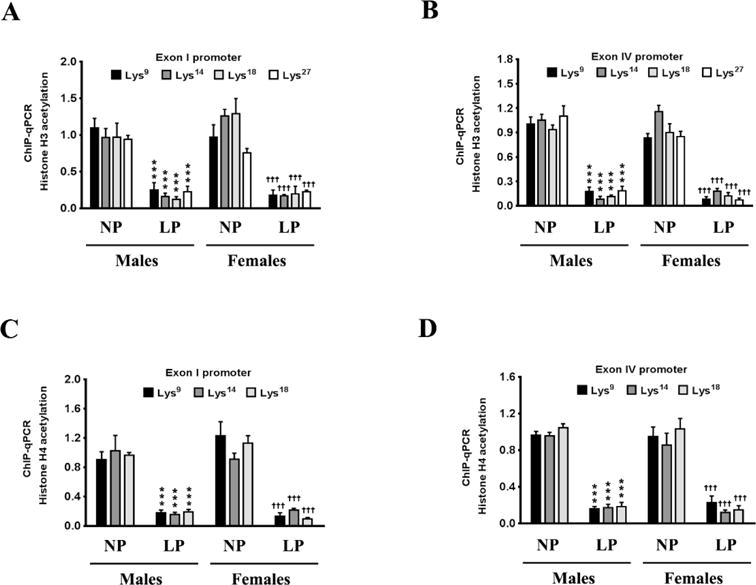

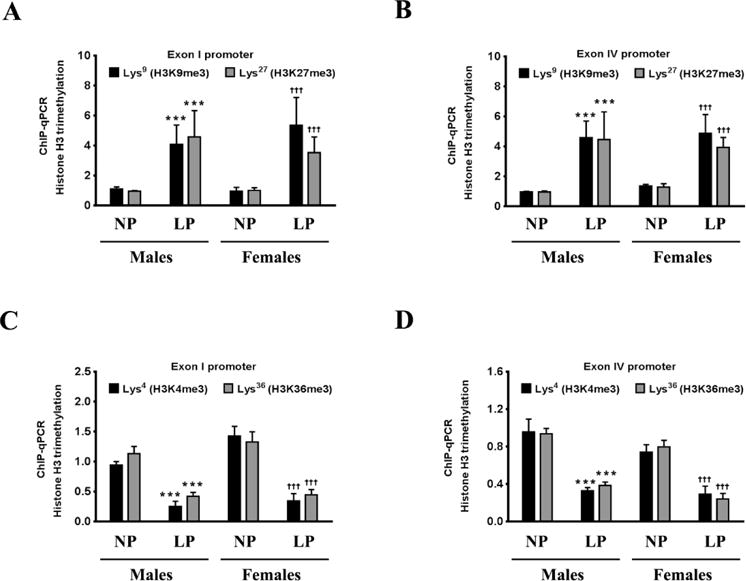

The phosphorylation of the PKA-Cα at Thr197 and PKA-Cβ at Ser338 results in their nuclear translocation where they phosphorylate CREB at the Ser133 residue and subsequently activate CREB to induce its transcriptional activity [58, 59]. We determined the levels of CREB phosphorylated at the Ser133 residue in the nuclear homogenates. The levels of p-Ser133 CREB were significantly decreased in the nuclear homogenates from the brains of the neonatal offspring that were exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 3A, 3B). As the levels of p-Ser133 CREB were significantly decreased, we next determined the transcriptional activity of CREB. The transcriptional activity of CREB was also significantly reduced commensurately, by 42% and 35% in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring respectively that were exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 3C). As CREB is one of the primary transcription factors regulating the expression of BDNF [23], we performed ChIP analysis to determine the extent of CREB binding in the BDNF promoter region. The rodent BDNF gene has nine transcription start sites (TSS), each one preceded by a promoter region [45, 60]. Of all the known promoters of the BDNF gene, exon I promoter and exon IV promoter are the best characterized in terms of mapping the cis and trans-regulating response elements driving the transcription [45, 61]. We determined the extent of CREB binding to the CRE site that is situated 79bp upstream (−79bp) of the TSS in exon I promoter and 29bp upstream (−29bp) of the TSS in exon IV promoter [50, 61]. We found a profound decrease in the binding of CREB at both the aforementioned CRE sites in the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter (Fig 3D) of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet. We measured the levels of chromatin-bound transcriptional coactivators of CREB, namely — p300, CREB-binding protein (CBP), and CREB regulated transcription coactivator 2 (CRTC2), that were associated with the CREB. Western blotting analysis on the CREB-ChIP samples after reverse cross-linking the chromatin showed a substantial reduction in the levels of p300, CBP, and CRTC2 co-immunoprecipitating with CREB (Fig 3E, 3F), thereby showing reduced activation of CREB in the brains of the neonatal offspring prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet. As the reduced binding of CREB in the BDNF promoter as well as attenuated CREB transcriptional activity does bot unequivocally translate into a reduction in CREB-mediated BDNF transcription, we determined the extent of histone acetylation in promoter I and promoter IV of BDNF as a positive marker of transcriptional activation. Acetylation of N-terminal residues of Histone H3 and Histone H4 makes the promoter more amenable for transactivation and subsequent transcription of the gene [62–64]. We performed ChIP analysis that entailed immunoprecipitating the chromatin with antibodies specific to the known lysine residues that are acetylated in N-terminus of Histone H3 and Histone H4 followed by amplifying the immunoprecipitated chromatin with sequence specific primers for BDNF exon I promoter and BDNF exon IV promoter. ChIP analysis revealed a significant reduction in acetylation of the Lys9 (H3K9ac), Lys14 (H3K14ac), Lys18 (H3K18ac), and Lys27 (H3K27ac) residues of Histone H3 in the exon I promoter (Fig 4A) and exon IV promoter (Fig 4B) of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 4A, 4B). There was also a significant mitigation in the acetylation of the Lys5 (H4K5ac), Lys8 (H4K8ac), and Lys12 (H4K12ac) residues of Histone H4 in the exon I promoter (Fig 4C) and exon IV promoter (Fig 4D) of BDNF in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (4C, 4D). We next determined the methylation status of the known Histone H3 and Histone H4 residues in the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene. Histone methylation at critical lysine residues in the promoters of genes bears a unique signature conferring the promoter to be in either the active state or the repressed (inactive) state [65–68]. Trimethylation of the Lys4 residue (H3K4me3) and Lys36 residue (H3K36me3) of Histone H3 is considered to be a signature of an active promoter and associated with transcriptional activation whereas trimethylation of the Lys9 residue (H3K9me3) and Lys27 residue (H3K27me3) of Histone H3 is considered to be a signature of a repressed promoter associated with transcriptional repression [69, 70]. ChIP analysis showed a significant enrichment of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, a unique signature of a repressed or an inactive promoter, in the exon I promoter (Fig 5A) and exon IV promoter (Fig 5B) of the Bdnf gene in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 5A, 5B). Furthermore, the levels H3K4me4 and H3K36me3 that are a hallmark of an active promoter and associated with transcriptional activation, were significantly decreased in the exon I promoter (Fig 5C) and exon IV promoter (Fig 5D) of the Bdnf gene in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet (Fig 5C, 5D).

Figure 3. Effects of maternal LP diet on CREB transcriptional activity and the subsequent binding of CREB to the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring.

(A, B) Representative western blots (A) and densitometric analysis (B) showing the effects of prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet on the activation phosphorylation at the Ser133 residue of CREB, in the whole brains of the neonatal offspring. (C) ELISA immunoassay showing the effects of a maternal LP diet on CREB transcriptional activity in the brains of the neonatal offspring. (D) ChIP-qPCR assay showing the effects of prenatal exposure to a LP diet on the binding of CREB to the CRE sites in the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring. (E, F) Representative western blots (E) and densitometric analysis (F) of the reverse cross-linked CREB-ChIP samples showing the extent of association of the known CREB coactivators, p300, CBP, and CRTC2, with the chromatin-bound CREB, in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet. Data is expressed as Mean ± S.D and includes determination made in six (n=6) different animals from each group. ***p<0.001 versus male neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet; ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001 versus female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet.

Figure 4. Effects of maternal LP diet on the acetylation of the known lysine residues of Histone H3 and Histone H4 in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring.

(A–D) ChIP-qPCR analysis shows that a maternal LP diet results in a non-permissive chromatin in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring. The ChIP-qPCR data show a reduced enrichment of Histone H3 and Histone H4 acetylation in the nucleosomes that envelop the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene, in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet. Data is expressed as Mean ± S.D and includes determination made in six (n=6) different animals from each group. ***p<0.001 versus male neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet; †††p<0.001 versus female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet.

Figure 5. Maternal LP diet alters Histone H3 methylation in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring.

(A–D) ChIP-qPCR analysis shows that a maternal LP diet results in a non-permissive chromatin in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring. (A, B) The ChIP-qPCR data show an augmentation in the enrichment of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, a signature of an inactive or repressed promoter, in the nucleosomes that envelop the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene, in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet. (C, D) The ChIP-qPCR data also show a reduction in the enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K36me3, a signature of an active promoter, in the nucleosomes that envelop the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene, in the brains of the neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal LP diet. Data is expressed as Mean ± S.D and includes determination made in six (n=6) different animals from each group. ***p<0.001 versus male neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet; †††p<0.001 versus female neonatal offspring exposed prenatally to a maternal NP diet.

4. Discussion

Environmental stressors such as maternal protein malnutrition are known to increase the susceptibility of the neonatal offspring to neurodegenerative [71, 72] and psychiatric disorders [73, 74]. Maternal protein malnutrition is known to be associated with cognitive disabilities as well as deficits in the neonatal offspring’s visual and verbal recognition memory systems, [75]. Several rodent models have cogently shown that maternal protein malnutrition during gestation perturbs neural development and alters neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, neuronal migration, and functional neuronal plasticity in the fetus [76, 77]. In rodents, maternal protein malnutrition during gestation causes anatomic abnormalities in the hippocampal formation in the neonatal offspring [4], and decreases adult neurogenesis in the sub-granular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus and the sub-ventircular zone (SVZ) of the adult progeny [78]. Prenatal protein malnutrition also causes deficits in learning and memory [4] in adult rodents as a consequence of impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) [79]. Despite comprehensive evidence linking maternal protein malnutrition to perturbations in neural development, deficits in learning and memory, and to neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, no clear molecular link or mediator has been established as an underlying cause. Our study is the first to determine at the molecular level, the impact of a maternal LP diet on the expression of the neurotrophin, BDNF, in the brains of the neonatal rats exposed prenatally to a LP diet. BDNF expression plays an indispensable role in neural development, learning and memory, neurogenesis, synaptic transmission, and BDNF dysregulation is implicated in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [13].

Prenatal exposure to a maternal low protein diet and general maternal malnutrition during gestation is known to evoke long-term indelible psychopathological changes and increased susceptibility to metabolic diseases in the adult progeny. This forms the kernel of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) [80–82] that posits epigenetic changes during the prenatal and perinatal periods in response to maternal protein malnutrition and general maternal malnutrition as the instigating factor in programming the adult phenotype of the progeny. Furthermore maternal LP diets and maternal malnutrition during the prenatal and perinatal periods have been shown to evoke changes in affective behavior and elicit behavioral abnormalities in the adult progeny regardless of the amends and corrections in the dietary patterns and regimen [83, 84]. This has been attributed to profound changes in brain micro architecture and structural abnormalities that happen during the adversities encountered because of maternal protein malnutrition as well as global malnutrition during the prenatal and perinatal phases of brain development [85–87]. Furthermore, these deficits in brain microstructure organization and structural abnormalities cannot be resolved by correcting the protein deficiency in the diet fed to the offspring during the postnatal phase which is considered outside the bounds of the “critical period” that defines the structural developmental and organizational phase of brain development [4, 5].

Maternal protein energy malnutrition (PEM) is known to induce cognitive impairment as well as deficits in learning and memory in the adult progeny [88]. In rodents, prenatal exposure to maternal LP diets induces structural deficits in brain architecture caused by alterations in neuronal proliferation and differentiation, awry dendritic arborizations, differences in myelination, and impairments in synaptogenesis [4] that translate into long-term indelible adverse effects on cognition and behavioral abnormalities [71, 89]. Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal protein malnutrition in humans is associated with impairments in social maturity, deficits in visual acuity and motor performances and coordination, as well as lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores, in children of 6–8 years of age [90–93]. However, the studies included children who continued to be protein malnourished postnatally and exhibited growth retardation and stunting [90–93]. Maternal protein restriction during gestation is characterized as prenatal stress on fetal development that causes fluxes in the expression of fetal endocrine and growth factors [94–96] altering the brain microarchitecture and increasing the susceptibility of the offspring to psychiatric and metabolic disorders later in their adulthood. Maternal protein restriction during gestation leading to prenatal fetal stress causes derangements in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis of the offspring postnatally [97]. Prenatal stress-induced derangements in HPA axis have been shown to alter the expression of the glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the hippocampus, amygdala, as well as the prefrontal cortex regions and thereby change the emotional reactivity of the offspring to stressful stimuli in their adulthood [98–101]. In humans, data from the Dutch Hunger Winter 1944–1945 study [102–105] and the Chinese Famine study [106] show that prenatal stress-induced dysregulation in HPA axis of the fetus during gestation is associated with increased susceptibility of the adult individual to develop psychiatric disorders [83, 107–109]. A multitude of animal studies have delved into the effects of prenatal PEM during gestation and postnatal PEM on behavioral abnormalities in the adult progeny [92, 110]. The protein malnourished rat pups subjected to prenatal and postnatal PEM exhibit greater nesting period and passive [5] but lesser locomotor and exploratory behavior [111] during the preadolescent period while exhibiting aggressive and dominance behavior traits in adulthood [112]. Prenatal and postnatal PEM is also associated with deficits in spatial learning and memory in adult rats despite allowing nutritional recovery [113]. These deficits in spatial learning and memory are attributed to structural anomalies in the hippocampal formation [4] and the dysfunction of the hippocampal cholinergic system [114]. Prenatal and postnatal PEM elicit impairments in long-term memory, working memory, and recognition memory in rodents as determined by the Morris maze, active avoidance test, and novel object recognition paradigms respectively [115]. Prenatal PEM results in cognitive and behavioral inflexibility as well as inadaptability in adult rats as assessed by conditioned taste aversion (CTA), performance of differential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) operational tasks, and reversal learning in a T-maze [5]. Postnatal PEM also causes somatosensory and motor deficits in rats when subjected a standard battery of paradigms that include determination of righting reflex, cliff avoidance test, negative geotaxis, and forelimb grip-strength tests [88]. In light of the aforementioned effects of prenatal PEM on behavior as well as somatosensory and motor deficits, there is significant evidence that prenatal PEM causes fluxes in levels of the neurotransmitters and the functioning of the neurotransmitter systems [107]. Prenatal and perinatal PEM has been shown to evoke an increase in release and turnover of dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) in the synapses [110, 116]. This increase in dopamine and serotonin was ascribed to an increase in the bioavailability of the precursor amino acids, tyrosine and tryptophan, respectively [117–119]. However, there was a net decrease in the dopamine concentration in the striatum and other dopaminergic tracts while a net increase in the serotonin concentration in the whole brain [120–123] accompanied by an increase in serotonin turnover in the hippocampus [124]. Although this study did not measure the levels of different amino acids in the plasma and the brain in response to the diets, available data from previous studies has shown that, in the brain, the concentration of valine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine and tyrosine are higher in the LP diet fed group of rats (8.7% protein fed for 15 days) compared to the NP diet fed group [125]. Interestingly, the study also found that the influx of amino acids from the plasma into the brain correlated with plasma amino acid concentrations while the concentrations of brain tissue tyrosine and tryptophan were inversely proportional to the protein content of the diet [125]. These fluxes in the levels of amino acids in the brain could possibly impinge on the mechanisms that underlie the maternal LP diet-induced decreases in the BDNF expression and CREB-mediated gene activation and transcription in the brain. Our ongoing work and future studies are aimed at measuring the plasma and brain levels of the key amino acids in response to the respective diets and deciphering the disparities in the brain levels of amino acids as well as how it may putatively translate and impinge on CREB-mediated BDNF expression.

The role of the cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling pathway has been extensively characterized in the positive regulation of BDNF expression [23]. Our study implicates the negative regulation of this pathway in the maternal LP diet-induced negative regulation of BDNF expression. We show direct evidence of decreased CREB-driven BDNF promoter transactivation and associated histone modifications that make the promoter of BDNF refractory to transactivation in response to prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet. Environmental challenges and noxious stimuli have been known to cause repressive histone H3 methylation in the promoters of BDNF gene and thereby decrease BDNF expression in the rodent brains [126–128]. Our study is the first to show a trans-generational effect of a maternal LP diet causing repressive Histone H3 and Histone H4 methylation in the BDNF promoters and consequently reduced expression of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal offspring. Inherited patterns of epigenetic reprograming as a consequence of differential Histone H3 acetylation in the rodent Bdnf promoters leading to alterations in BDNF expression in the progeny have been observed in rodent models that study cocaine addiction during gestation [129]. Our study is unique in that it found that a maternal LP diet induces decreased acetylation of known lysine residues in Histone H3 and Histone H4 in the exon I and exon IV promoters of the rat Bdnf gene, that signify trans-repression of the Bdnf gene, in the brains of the neonatal progeny. Only one contemporary study has delved into the effects of a maternal LP diet on long-term potentiation (LTP), a molecular correlate of learning and memory, and BDNF expression in the neonatal progeny and found that prenatal protein malnutrition results in the deficits in LTP generation and induction in BDNF expression in response to a tetanizing stimulation of the entorhinal cortex (EC) and the CA1 region of the hippocampus [79]. That study by Hernandez et al. differed from our study in that it determined the tetanizing stimulation-evoked increase in BDNF expression in the rats prenatally exposed to a LP diet, while our study determined the basal BDNF levels in the neonatal offspring prenatally exposed a LP diet. Furthermore, our study is the first to delineate and characterize the molecular mechanism at the level of gene transcription, while the study by Hernandez et al. [79] determined the ability of a tetanizing stimulation to induce BDNF expression postnatally in the progeny that were subjected to a maternal LP diet prenatally.

Histone acetylation is an indispensable epigenetic modification that is needed for CREB transcriptional activity and CREB-induced transactivation of a multitude of genes [130]. It is known that CREB binding to the CRE in the promoter region of target genes recruits the CBP/p300 co-activator complex, with histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity, leading to an increase in the known lysine residues of Histone H3 and Histone H4 in the promoters of target genes leading to their transactivation [130]. We found a profound decrease in CREB binding to the CRE in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene in the brains of the neonatal rats exposed prenatally to a LP diet. This was accompanied by reduced CREB transcriptional activity and a commensurate decrease in the acetylation of the known lysine residues of Histone H3 and Histone H4 in the exon I promoter and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene. Chronic psychiatric stress has been shown to increase the trimethylation of the Lys27 residue of Histone H3 methylation (H3K27me3) in the exon IV promoter Bdnf gene that results in attenuated Bdnf expression and is associated with clinical depression [131, 132]. We found that prenatal exposure to a LP diet resulted in a pronounced increase in the trimethylation of the Lys9 and Lys27 residues of Histone H3 in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene, that are associated with reduced expression of the Bdnf gene. We further discovered that a maternal LP diet resulted in the decreased enrichment of trimethylation at Lys4 and Lys36 residues of Histone H3 in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene, that is associated with increased Bdnf expression, in the brains of male and female neonatal offspring. Our study therefore is the first that unequivocally shows that prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet results in inherited epigenetic changes characterized by fluxes in the acetylation and methylation profile of Histone H3 and Histone H4 in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene that culminates in attenuated CREB-mediated and CREB-driven transcription of Bdnf.

Epigenetic regulation involving fluxes in histone modifications of the Bdnf gene promoters have been identified and characterized in rodent models of learning and memory [133, 134]. However, no study has determined a transgenerational effect of a maternal LP diet on the acetylation and methylation status of Histone H3 and H4 in the Bdnf gene promoters. We delineated one of molecular mechanisms, a downregulation in cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling cascade accompanied by a histone modification changes in the exon I and exon IV promoter of the Bdnf gene that mediates the repressive effect of a maternal LP diet on Bdnf expression in the neonatal offspring. However, questions remained unanswered with regards to the molecular mediators effectuating a decrease in Histone H3 and H4 acetylation as well as an increase in repressive methylation (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) accompanied by a decrease in activating methylation (H3K4me3 and H3K36me3) in the Histone H3 and H4 that form the core of the nucleosomes that envelope Bdnf promoters. Further studies are warranted to determine the effects of prenatal exposure to a maternal LP diet on the activity and expression of canonical bonafide histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) as well as the histone-lysine N-methyltransferases (HKMTs) and histone-lysine demethylases (HKDs) and the fluxes in the dynamic interplay among them. In light of this, the expression of other key neurotrophic factors and neural proteins could be altered in the brains of the neonatal offspring that are prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet. The changes that we observed in the acetylation and methylation of known histone residues in the nucleosomes that envelope the Bdnf promoter could be a diverse global effect across the epigenome. Indeed, preliminary data from our other studies have shown changes in the expression of leptin, Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF1), and Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF) in the brains of neonatal offspring prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet. Our contemporary and on-going studies have indeed unveiled changes in the histone acetylation and methylation in the nucleosomes enveloping the leptin promoter. Furthermore, DNA methylation of the leptin promoter itself is altered in the brains of the neonatal rats prenatally exposed to a maternal LP diet. Taken together, our results suggest that a maternal diet that is low in protein can have deleterious effects in neonates. Specifically, neonates can exhibit learning and memory deficits as well as other degenerative effects that are associated with decreased levels of the neurotrophic factors BDNF and CREB.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Ms. Amy Bundy for providing technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, Grant # R01AG0145264, to Dr. Othman Ghribi. This work was also supported by USDA Agricultural Research Service Project #3062-51000-052-00D to Dr. Kate Claycombe.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jahan-Mihan A, Rodriguez J, Christie C, Sadeghi M, Zerbe T. The Role of Maternal Dietary Proteins in Development of Metabolic Syndrome in Offspring. Nutrients. 2015;7:9185–217. doi: 10.3390/nu7115460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores O, Perez H, Valladares L, Morgan C, Gatica A, Burgos H, et al. Hidden prenatal malnutrition in the rat: role of beta(1)-adrenoceptors on synaptic plasticity in the frontal cortex. J Neurochem. 2011;119:314–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgane PJ, Austin-LaFrance R, Bronzino J, Tonkiss J, Diaz-Cintra S, Cintra L, et al. Prenatal malnutrition and development of the brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1993;17:91–128. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgane PJ, Mokler DJ, Galler JR. Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition on the hippocampal formation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:471–83. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonkiss J, Galler J, Morgane PJ, Bronzino JD, Austin-LaFrance RJ. Prenatal protein malnutrition and postnatal brain function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;678:215–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Garcia G, Guzman-Quevedo O, Da Silva Aragao R, Bolanos-Jimenez F. Early malnutrition results in long-lasting impairments in pattern-separation for overlapping novel object and novel location memories and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21275. doi: 10.1038/srep21275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick O, Miller M, Forbes W, Hall R, Kemper T, Bronzino J, et al. Developmental protein malnutrition: influences on the central nervous system of the rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1979;3:233–46. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(79)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennis-Taleb N, Remacle C, Hoet JJ, Reusens B. A low-protein isocaloric diet during gestation affects brain development and alters permanently cerebral cortex blood vessels in rat offspring. J Nutr. 1999;129:1613–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.8.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher EA, Newman JP, Green LR, Hanson MA. The effect of low protein diet in pregnancy on the development of brain metabolism in rat offspring. J Physiol. 2005;568:553–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claycombe KJ, Uthus EO, Roemmich JN, Johnson LK, Johnson WT. Prenatal low-protein and postnatal high-fat diets induce rapid adipose tissue growth by inducing Igf2 expression in Sprague Dawley rat offspring. J Nutr. 2013;143:1533–9. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.178038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Pan S, Li X, Sun Q, Yang X, Zhao R. Maternal low-protein diet affects myostatin signaling and protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of offspring piglets at weaning stage. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:971–9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Khattabi I, Gregoire F, Remacle C, Reusens B. Isocaloric maternal low-protein diet alters IGF-I, IGFBPs, and hepatocyte proliferation in the fetal rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E991–E1000. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binder DK, Scharfman HE. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors. 2004;22:123–31. doi: 10.1080/08977190410001723308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaillant AR, Mazzoni I, Tudan C, Boudreau M, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Depolarization and neurotrophins converge on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway to synergistically regulate neuronal survival. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:955–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramar EA, Chen LY, Lauterborn JC, Simmons DA, Gall CM, Lynch G. BDNF upregulation rescues synaptic plasticity in middle-aged ovariectomized rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:708–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAllister AK, Katz LC, Lo DC. Neurotrophins and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:295–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marosi K, Mattson MP. BDNF mediates adaptive brain and body responses to energetic challenges. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa T, Ono-Kishino M, Sugaru E, Yamanaka M, Taiji M, Noguchi H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) regulates glucose and energy metabolism in diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:185–91. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchida A, Nonomura T, Nakagawa T, Itakura Y, Ono-Kishino M, Yamanaka M, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor ameliorates lipid metabolism in diabetic mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2002;4:262–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2002.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Autry AE, Monteggia LM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:238–58. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barde YA, Edgar D, Thoenen H. Purification of a new neurotrophic factor from mammalian brain. EMBO J. 1982;1:549–53. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkbeiner S, Tavazoie SF, Maloratsky A, Jacobs KM, Harris KM, Greenberg ME. CREB: a major mediator of neuronal neurotrophin responses. Neuron. 1997;19:1031–47. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meinkoth JL, Alberts AS, Went W, Fantozzi D, Taylor SS, Hagiwara M, et al. Signal transduction through the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;127–128:179–86. doi: 10.1007/BF01076769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlezon WA, Jr, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIlroy PJ, Kocsis JF, Weber H, Carsia RV. Dietary protein restriction stress in the domestic fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus) alters adrenocorticotropin-transmembranous signaling and corticosterone negative feedback in adrenal steroidogenic cells. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1999;113:255–66. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milanski M, Arantes VC, Ferreira F, de Barros Reis MA, Carneiro EM, Boschero AC, et al. Low-protein diets reduce PKAalpha expression in islets from pregnant rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:1873–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claycombe KJ, Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Roemmich JN, Rhen T, Ghribi O. Maternal low-protein diet causes body weight loss in male, neonate Sprague-Dawley rats involving UCP-1-mediated thermogenesis. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claycombe KJ, Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Roemmich JN, Rhen T, Ghribi O. Maternal low-protein diet causes body weight loss in male, neonate Sprague-Dawley rats involving UCP-1-mediated thermogenesis. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marwarha G, Prasanthi JR, Schommer J, Dasari B, Ghribi O. Molecular interplay between leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1, and beta-amyloid in organotypic slices from rabbit hippocampus. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marwarha G, Dasari B, Ghribi O. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced CHOP activation mediates the down-regulation of leptin in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells treated with the oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol. Cell Signal. 2012;24:484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marwarha G, Raza S, Meiers C, Ghribi O. Leptin attenuates BACE1 expression and amyloid-beta genesis via the activation of SIRT1 signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1587–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marwarha G, Raza S, Prasanthi JR, Ghribi O. Gadd153 and NF-kappaB crosstalk regulates 27-hydroxycholesterol-induced increase in BACE1 and beta-amyloid production in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Marwarha G, Dasari B, Prabhakara JP, Schommer J, Ghribi O. beta-Amyloid regulates leptin expression and tau phosphorylation through the mTORC1 signaling pathway. J Neurochem. 2010;115:373–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marwarha G, Berry DC, Croniger CM, Noy N. The retinol esterifying enzyme LRAT supports cell signaling by retinol-binding protein and its receptor STRA6. FASEB J. 2014;28:26–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-234310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claude A. Fractionation of mammalian liver cells by differential centrifugation; problems, methods, and preparation of extract. J Exp Med. 1946;84:51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claude A. Fractionation of mammalian liver cells by differential centrifugation; experimental procedures and results. J Exp Med. 1946;84:61–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marwarha G, Dasari B, Prasanthi JR, Schommer J, Ghribi O. Leptin reduces the accumulation of Abeta and phosphorylated tau induced by 27-hydroxycholesterol in rabbit organotypic slices. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1007–19. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marwarha G, Claycombe K, Schommer J, Collins D, Ghribi O. Palmitate-induced Endoplasmic Reticulum stress and subsequent C/EBPalpha Homologous Protein activation attenuates leptin and Insulin-like growth factor 1 expression in the brain. Cell Signal. 2016;28:1789–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marwarha G, Rhen T, Schommer T, Ghribi O. The oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol regulates alpha-synuclein and tyrosine hydroxylase expression levels in human neuroblastoma cells through modulation of liver X receptors and estrogen receptors-relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2011;119:1119–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Malcangio M. Neurotrophin secretion: current facts and future prospects. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:341–74. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woo NH, Teng HK, Siao CJ, Chiaruttini C, Pang PT, Milner TA, et al. Activation of p75NTR by proBDNF facilitates hippocampal long-term depression. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1069–77. doi: 10.1038/nn1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumoto T, Rauskolb S, Polack M, Klose J, Kolbeck R, Korte M, et al. Biosynthesis and processing of endogenous BDNF: CNS neurons store and secrete BDNF, not pro-BDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:131–3. doi: 10.1038/nn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Siao CJ, Nagappan G, Marinic T, Jing D, McGrath K, et al. Neuronal release of proBDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:113–5. doi: 10.1038/nn.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:525–35. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu QR, Lu L, Zhu XG, Gong JP, Shaham Y, Uhl GR. Rodent BDNF genes, novel promoters, novel splice variants, and regulation by cocaine. Brain Res. 2006;1067:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caruso C, Carniglia L, Durand D, Gonzalez PV, Scimonelli TN, Lasaga M. Melanocortin 4 receptor activation induces brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in rat astrocytes through cyclic AMP-protein kinase A pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ou LC, Gean PW. Transcriptional regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the amygdala during consolidation of fear memory. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:350–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shieh PB, Hu SC, Bobb K, Timmusk T, Ghosh A. Identification of a signaling pathway involved in calcium regulation of BDNF expression. Neuron. 1998;20:727–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tao X, Finkbeiner S, Arnold DB, Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 1998;20:709–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabuchi A, Sakaya H, Kisukeda T, Fushiki H, Tsuda M. Involvement of an upstream stimulatory factor as well as cAMP-responsive element-binding protein in the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene promoter I. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35920–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaccolo M, Magalhaes P, Pozzan T. Compartmentalisation of cAMP and Ca(2+) signals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:160–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walsh DA, Perkins JP, Krebs EG. An adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependant protein kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3763–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor SS, Kim C, Vigil D, Haste NM, Yang J, Wu J, et al. Dynamics of signaling by PKA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor SS, Yang J, Wu J, Haste NM, Radzio-Andzelm E, Anand G. PKA: a portrait of protein kinase dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:259–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor SS, Kim C, Cheng CY, Brown SH, Wu J, Kannan N. Signaling through cAMP and cAMP-dependent protein kinase: diverse strategies for drug design. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams JA, McGlone ML, Gibson R, Taylor SS. Phosphorylation modulates catalytic function and regulation in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2447–54. doi: 10.1021/bi00008a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR. Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell. 1989;59:675–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto KK, Gonzalez GA, Biggs WH, 3rd, Montminy MR. Phosphorylation-induced binding and transcriptional efficacy of nuclear factor CREB. Nature. 1988;334:494–8. doi: 10.1038/334494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Timmusk T, Palm K, Metsis M, Reintam T, Paalme V, Saarma M, et al. Multiple promoters direct tissue-specific expression of the rat BDNF gene. Neuron. 1993;10:475–89. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90335-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng F, Zhou X, Moon C, Wang H. Regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in neurons. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2012;4:188–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vogelauer M, Wu J, Suka N, Grunstein M. Global histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature. 2000;408:495–8. doi: 10.1038/35044127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suka N, Suka Y, Carmen AA, Wu J, Grunstein M. Highly specific antibodies determine histone acetylation site usage in yeast heterochromatin and euchromatin. Mol Cell. 2001;8:473–9. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eberharter A, Becker PB. Histone acetylation: a switch between repressive and permissive chromatin. Second in review series on chromatin dynamics. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:224–9. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–49. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–95. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peterson CL, Laniel MA. Histones and histone modifications. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343–57. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell. 2012;48:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]