Abstract

Background

Women with physical disabilities are known to experience disparities in maternity care access and quality, and communication gaps with maternity care providers, however there is little research exploring the maternity care experiences women with physical disabilities from the perspective of their health care practitioners.

Objective

This study explored health care practitioners’ experiences and needs around providing perinatal care to women with physical disabilities in order to identify potential drivers of these disparities.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with 14 health care practitioners in the United States who provide maternity care to women with physical disabilities, as identified by affiliation with disability-related organizations, publications and snowball sampling. Descriptive coding and content analysis techniques were used to develop an iterative code book related to barriers to caring for this population. Public health theory regarding levels of barriers was applied to generate broad barrier categories, which were then analyzed using content analysis.

Results

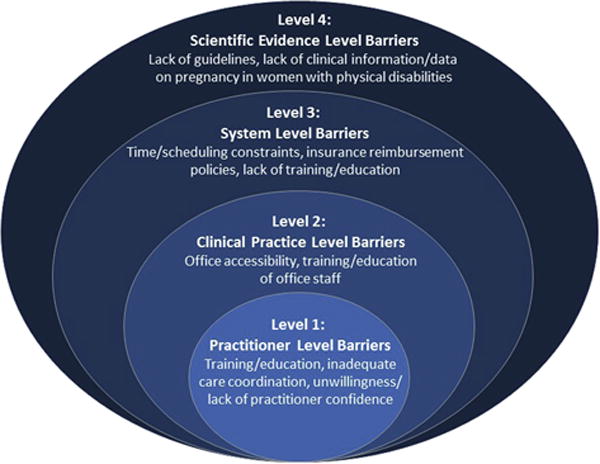

Participant-reported barriers to providing optimal maternity care to women with physical disabilities were grouped into four levels: practitioner level (e.g., unwillingness to provide care), clinical practice level (e.g., accessible office equipment like adjustable exam tables), system level (e.g., time limits, reimbursement policies), and barriers relating to lack of scientific evidence (e.g., lack of disability-specific clinical data).

Conclusion

Participants endorsed barriers to providing optimal maternity care to women with physical disabilities. Our findings highlight the needs for maternity care practice guidelines for women with physical disabilities, and for training and education regarding the maternity care needs of this population.

Keywords: disability, perinatal care, pregnancy, prenatal care, women’s health

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies of unmet needs and barriers to maternity care for women with physical disabilities demonstrated that women experienced complex interactions with their maternity care providers.1, 2 While many women experienced their provider as supportive, compassionate and helpful, women also perceived negative attitudes and stereotypes about the sexuality and motherhood of women with physical disabilities from providers. Women reported a lack of knowledge on the part of the practitioner about their specific needs related to pregnancy, inaccessible health care settings including health care offices, equipment and birth facilities, and perceived failure of practitioners to consider the woman’s knowledge and expertise related to her own disability.1, 2 Similar findings have been noted in other studies of maternity care experiences and outcomes of women with various disabilities, including physical disabilities.3–6

Though these communication gaps and attitudinal barriers reflect the interactions and experiences of men and women with disabilities with the larger health care system,7–9 there is a paucity of research exploring the maternity care experiences of U.S. women with physical disabilities from the perspective of their health care practitioners. This study explored maternity care providers’ experiences and challenges in caring for women with physical disabilities in the United States. This is part of a larger mixed-method study to understand the unmet needs and barriers to perinatal care among women with physical disabilities.

METHODS

The researchers recruited 14 obstetrician-gynecologists and certified nurse midwives with experience providing maternity care to women with physical disabilities. Practitioners were identified and recruited through the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American College of Nurse Midwives, affiliations with disability-related organizations, publications in the area of pregnancy and disability, indications of work with women with physical disabilities in online professional profiles, and snowball sampling. The study team reached out to the identified health care practitioners to confirm experience caring for pregnant women with physical disabilities and invited them to participate in individual semi-structured telephone interviews. Informed consent was obtained during the scheduling process.

The researchers identified and contacted 33 health care practitioners in February through April of 2015. Sixteen practitioners were unable to be reached and/or scheduled, and an additional three stated that they did not have sufficient experience caring for women with physical disabilities. The researchers conducted and analyzed 14 semi-structured interviews, which lasted an average of 45 minutes each.

All interviews were conducted over the phone by a study co-investigator who is also a health care practitioner. Interviews were audio-recorded with the participant’s consent and then professionally transcribed. After collecting details about the practice and experience caring for women with physical disabilities, our interview guide focused on participant perceptions of unmet needs/barriers for women with physical disabilities related to maternity care and birth and barriers for health care practitioners in caring for women with physical disabilities. Participants were also asked about their perceptions regarding the utility of developing guidelines or practice recommendations and their recommendations for other health care practitioners related to caring for this population.

For this preliminary review of a novel topic, the researchers chose to use a process that was intended to be descriptive and not to generate theory. As an initial step, four investigators independently generated descriptive codes through reviewing two transcripts each. The codes were then discussed and refined in a series of team meetings and a descriptive codebook was developed based on the descriptors present in the data, as well as thorough review of the literature and application of public health theory. Next, one primary coder then applied the codebook to all 14 transcripts using descriptive analysis, and codes were further modified and revised throughout this process. The primary coder met with the principal investigator frequently to further refine the codebook in response to issues that arose within the data and inter-coder conflict. Inter-coder conflicts were settled by consensus. After codes were generated and all transcripts coded, we applied a theory driven conceptual framework developed from our knowledge of public health theory, a deductive qualitative technique that has been used by other health services researchers in tight, results-oriented qualitative designs.10 Our application of social science/public health theory focused on organizing the codes into four levels of barriers, which were identified using theming. Atlas.ti version 7 was used to manage the codes.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Brandeis University, University of Massachusetts Medical School and Villanova University School of Nursing Institutional Review Boards.

RESULTS

The sample included health care practitioners with expertise in obstetrics/gynecology, maternal-fetal medicine, certified nurse midwifery, and medical genetics. The participants had an average of 22 years of experience caring for pregnant women with physical disabilities, with a range of 6 to 40 years of experience. They cared for a varying volume of women with physical disabilities, with a range of a few per year to five or more per month. The participants practiced in a variety of settings, including hospitals, university practices, solo practices, and specialty clinics specifically for women with disabilities. They reported providing care to women with a range of physical disabilities including multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, amputation, and dwarfism, among others. Most of the participants are currently seeing women with physical disabilities in their practices. Several previously worked in practices where they saw women with disabilities but they have since moved to different practices.

Numerous barriers were identified through our descriptive analysis and were grouped into four levels of barriers: Practitioner level; Clinical practice level; System level; and Barriers relating to lack of scientific evidence. Figure 1 depicts the levels of barriers and Table 1 summarizes the identified barriers, with representative quotes.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

| Practitioner-level barriers | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Lack of training and education related to prenatal care and the specific clinical needs of women with physical disabilities | “…I would have loved to have more information about how CP and some of the other issues affect people’s mobility… almost like a PT crash course in how to manage or understand what’s going on with people’s musculature…” |

| Inadequate coordination of care between providers | “…when someone would come to us for GYN care, if they were a new person that we hadn’t seen a lot before… you really didn’t have any access or any way other than looking at a paper chart, which wasn’t always complete and which didn’t give you much more information besides somebody’s medication list… So I think that there’s a lot that could be done to expand continuity of care. |

| Unwillingness and in some cases a lack of confidence in the skills of clinicians providing prenatal care to women with physical disabilities | “Inexperience and I think just anxiety and fear that they wouldn’t know how to properly take care of the patient and especially just getting the patient on the exam table. They don’t know how to do that, don’t have the right equipment to make it easy.” |

| Clinical practice-level barriers | |

| Inaccessible facilities and equipment | “Weighing [women with physical disabilities” is difficult, because we’re not set up to have a wheelchair scale. That is definitely a problem. Our rooms are big enough, but it’s still tight. So physically you can do it, it’s just a little bit tight getting in.” |

| Staff training/education | “…that’s one of the best things about our clinic is we do have a dedicated RN… and she’s extremely knowledgeable both in… gynecologic care and even with the disabled. And same for our medical assistant.” |

| System-level barriers | |

| Time/scheduling constraints | ”…even when we had people in for an hour slot it sometimes took longer than that just to do everything that needed to be done. So I think those are definite barriers. And I think that those are other reasons why people are hesitant to try to weave these kinds of people with needs – these kinds of needs into their practice. Because it’s difficult.” |

| Insurance reimbursement policies | “…any other job, you work harder, you get paid more. Not in medicine… If I do a surgery that’s really easy and I do the exact same operation in name on another patient and it takes me four times as long, I get paid the same amount. That’s the way it is.” |

| Scientific evidence-level barriers | |

| Lack of available disability-specific clinical information and/or data on the interaction of disability and pregnancy | “Providers need to know how to test for urinary tract infection, how to treat urinary tract infection, whether to give prophylactics or DBTs for embolism, et cetera” |

| Lack of available guidelines | “I know whenever I see someone, and it’s always kind of a unique thing, I’m scrambling around trying to look at a bunch of different references, trying to figure out what’s best for that individual. So it would be nice to have it tucked into a nice little reference.” |

| Lack of training, and education | “[Medical school is] really where you start – I mean, that’s where the culture begins. And for OB/GYNs, once they get their residency, they should be in a program where you get [pregnancy in women with physical disabilities] as a focus. |

Practitioner Level Barriers

Participants described several practitioner level barriers to optimal maternity care for women with physical disabilities, including (1) practitioner lack of training and education related to maternity care and specific clinical needs of women with physical disabilities (in general), (2) unwillingness and, in some cases a lack of confidence, among practitioners in general in providing maternity care to women with physical disabilities, and (3) inadequate coordination of care between practitioners.

Almost all participants described a lack of education and training related to the maternity care needs of women with physical disabilities. As noted by one practitioner, “It would be really great if during fellowship there was something, or even during residency there was some sort of … educational tool to … help us out.” participants felt that this lack of training can lead to extremely uncomfortable experiences for women with physical disabilities. “You’re trying to do your best, but if you haven’t been educated on specifically how to work with people that have contracted muscles, for example, it’s kind of hard to get them in a position comfortably where you can… insert a speculum and do … a GYN exam. It can be … incredibly traumatic.” One participant noted that formal education and training early on could possibly prevent practitioner bias towards pregnant women with physical disabilities “So we do have our own prejudices about disabilities. Whether it’s the baby or the patient. And I guess some kind of – some kind of open-mindedness about that early on would be helpful. I don’t know how you do that, except maybe going back to medical school, as before anybody even picks their field.”

The participants also described a general lack of confidence among practitioners about ability to provide adequate maternity care to women with physical disabilities. Many of the participants attributed this lack of confidence to lack of training and/or experience caring for women with physical disabilities, which in turn may lead some practitioners to refer patients with disabilities out of their practices when it may otherwise not be indicated. “I think…physicians feel uncomfortable, untrained, unprepared, and their offices are also equally untrained and unprepared… So unfortunately, they [patients with disabilities] end up in a perinatology office just because they have a physical disability, not because they truly have an unusual obstetrical clinical problem.”

The practitioners also described barriers to provider-initiated care coordination, which they felt was an important element of successful care of women with physical disabilities. The practitioners recognized the benefit of strategies like consulting with an anesthesiologist to plan for delivery or contacting the woman’s other providers to gain additional understanding of her medical history and/or her disability, but felt that their ability to do so was constrained by external factors. “…you really didn’t have any access or any way other than looking at a paper chart, which wasn’t always complete and which didn’t give you much more information besides somebody’s medication list… So I think that there’s a lot that could be done to expand continuity of care.” As many women with complex disabilities have long-standing relationships with non-pregnancy related practitioners, participants felt it was important to involve these practitioners in the maternity care process “so that the patient doesn’t have to have a brand new neurologist or internist so …, that the ones [who]… know them well stay in the mix.”

Clinical Practice Level Barriers

Clinical practice level barriers to providing optimal maternity care to women with physical disabilities included (1) inaccessible health care facilities and equipment and (2) need for education and training among office staff.

Inaccessible equipment was reported by many participants as a barrier to caring women with physical disabilities. Although some personally had accessible equipment such as examination tables that raise and lower and wheelchair accessible exam rooms, they noted that such equipment is not common place. Without such equipment, it can be more difficult and time-consuming to provide care to women with physical disabilities. “Patients can transfer if they’re in a wheelchair …for the ultrasound, for vaginal examinations, on their own, because we can lower the beds to the level of the wheelchair and we didn’t have this ability just a few years ago. It’s relatively new, and makes a big difference for the patients clearly to be able to transfer.” Notably, even in our sample of health care professionals who had substantial experience caring for patients with physical disabilities, very few reported that they had accessible scales that could accommodate patients who used wheelchair, described by this participant, “We have a wheelchair scale. So we weigh the patient in the wheelchair, then weigh the wheelchair without the patient… Many of our patients say they’ve never been weighed…” One participant noted that “they sometimes get weighed at their other [doctors] that are taking care of them …the neurologists or rehab medicine … we kind of rely on them, if they can’t get out of their wheelchair.” Another health care professional similarly stated that, “we had to rely on the number that was there from their most recent physical.” Another stated that, “I generally just eyeball. We spend a lot of time talking about it.”

Although many participants reported having a relatively disability-knowledgeable staff, they noted lack of training of office, medical and other support staff in working with people with disabilities as a barrier affecting practices in general. One participant said, “I think that they [staff in my office] could be more knowledgeable, but are probably more knowledgeable than other office staffs… I certainly think that there is tremendous areas for improvement.”

System-Level Barriers

Systems-level barriers to caring for women with physical disabilities during pregnancy include: (1) Time/scheduling constraints, and (2) Insurance reimbursement policies.

The barriers posed by the challenges of allocating the time necessary to provide appropriate treatment for women with physical disabilities were a frequently recurring theme in these interviews. Participants spoke about the pressure to keep appointment times within prescribed time slots (often 10 or 15 minutes), potentially compromising care to women who may require additional time, such as women with physical disabilities who might need as much as 3 or 4 times the allotted appointment time. “We are so locked into these 15- and 30-minute slots now, in medical practice, that it’s very hard … for any one doc[tor] to isolate an hour or an hour and a half for a patient visiting. And many of these patients will take an hour.” As another participant noted, a typical prenatal visit “is 10 minutes, and we might schedule that person for 45 minutes, recognizing that there’s going to be extra time needed for the other aspects of her care… that’s a luxury that I have that a lot of OB/GYNs don’t have.”

Low payment rates and complex reimbursement was another commonly cited system-level barrier. Health care professionals are typically reimbursed for the services rendered regardless of time spent with the patient. The issue of time is tied closely with insurance reimbursement. As one provider noted, “you don’t get paid any extra. You do this because it’s the right thing to do and you want to do it and you love to do it and the patients appreciate it. And that’s why you do it. You don’t do it for money. It’s a money loser. No insurance company, whether it’s commercial, state, or federal, is going to pay me more.” One participant noted that the reimbursement structure made it difficult “to spend the extra time that it takes to get somebody in and out of a wheelchair, in and out of a room, to try to figure out the care and coordinate it.” In addition, participants felt that there were “many practices out there who don’t feel the need to care for anybody that has… anything other [than] private insurance” and in fact, one participant noted that “…none of our private practices will take patients with Medicare. Period, end of story.”

Barriers Related to Lack of Evidence

Barriers related to a general lack of available evidence for providers on pregnancy in women with physical disabilities included (1) Lack of maternity practice guides and (2) Lack of disability-specific clinical information and data on the interaction of disability and pregnancy.

A majority of participants reported that perinatal care guidelines for women with physical disabilities would be helpful, though few participants were aware of any existing guidelines or practice recommendations. In particular, “Some sort of collaborative practice guidelines from professional societies that are multidisciplinary in nature … would be good.” However, one participant expressed that perinatal care guidelines would add little to their clinical experience. “I want a doctor that thinks, not in front of a computer because … my patients, particularly disabled patients, are not inside the paradigm, are not inside the guidelines or clinical pathway.”

Lack of available evidence-based clinical data related to pregnancy in women with physical disabilities was noted as a barrier by multiple health care practitioners, often in the context of the lack of practice guidelines. They noted that adequate strong clinical data and evidence about pregnancy in women with specific physical disabilities on which to base guidelines are lacking. For example, “the prevalence of thrombosis in pregnancy is like one per 1,000, or two per 1,000, so if it doubles it becomes four per 1,000, or even if it quintuples to 10 per 1,000, or 1%, so you need hundreds of women with spinal cord injuries before you notice that the prevalence of thrombosis or embolism is higher than expected.” The lack of information and evidence, participants felt, resulted in on-the-job learning and training, “in my general practice almost any decision I make, if I have any questions I can [go] to Up To Date or some sort of reference, ACOG recommendation, and they’ll tell me exactly what to do, but in the disability clinic that’s not the case. It’s almost the opposite. You have to use your clinical judgment.” Participants felt that they needed to extrapolate data about non-pregnant women and even men with disabilities to pregnant women.

DISCUSSION

This study examines barriers to optimal maternity care for women with physical disabilities from the perspectives of fourteen health care practitioners with substantial experience in providing maternity care to this population. Our findings highlight significant barriers at multiple levels.

Across levels, lack of training and education about the maternity care of women with physical disabilities was a significant factor in health care practitioner perceptions that women with physical disabilities did not always receive optimal maternity care. Participants noted that there were educational and knowledge gaps among health care practitioners, but also among office and medical support staff, and at the level of the system. Participants felt that the ability of maternity care health care practitioners to provide perinatal care to women with physical disabilities was severely impeded by the lack of disability training and exposure to women with physical disabilities in their medical education. While practitioner training and education related specifically to maternity care of women with physical disabilities has not been studied, the lack of education about health care and needs of people with disabilities is well documented across medical professions.11–14 Further, research about the importance of early and often education and exposure to people with disabilities in improving health care practitioner skill and willingness to care for this population is well documented,15 and should be applied to maternity care. Additionally, participants felt that disability education and training would reduce provider bias and prejudice towards providing care to people with disabilities, an idea that is supported by evidence related to general and specialty practice care of people with various disabilities.16–19

Training and education about the needs of patients with disabilities has not been studied extensively in office and medical support staff. However, interactions with such paraprofessionals have important impacts on patients’ perceptions of their care, including satisfaction with care.20–22 As exposure to and education about people with disabilities has been shown to increase acceptance of people with disabilities in the general public and members of other professions,23, 24 it stands to reason that such education could also be successful among medical office staff and paraprofessionals, representing a potentially useful strategy for improving maternity care of women with physical disabilities.

Another important theme raised by participants was the lack of a strong clinical evidence base on the effects of specific disabilities on pregnancy, and the associated lack of clinical guidelines. Although participants in this study noted a gap in this area, we acknowledge evidence-based medicine is only one part of medical practice and does not replace clinical judgment or patient-centered care. In addition, though participants described strategies and practice conditions that have allowed them to care successfully for women with physical disabilities, they noted that employing such strategies required a degree of flexibility that was not present in many maternity care practices and systems. Flexibility and patient centeredness is gaining recognition as particularly important in maternity care satisfaction and outcomes,25, 26 and may be even more important for women with physical disabilities.

Efforts to improve perinatal care for women with physical disabilities and address the health care practitioner level, clinical practice level, system-level, and scientific evidence-level barriers in the health care system need a multi-pronged approach. Important needs include ensuring the accessibility of health care settings, the inclusion of disability-related clinical learning experiences in maternity care training and education, as well as education and training for office staff, the development and dissemination of a base of evidence and data on the effects of specific disabilities on pregnancy, and relatedly, development and dissemination of perinatal practice guidelines specific to women with physical disabilities. Health care practitioners, professional organizations and federal agencies can take an affirmative step by requiring disability-related clinical training for maternity care providers, funding research studies to develop an evidence base, and developing and disseminating practice guidelines. Collectively, these efforts are vital to ensure women with physical disabilities receive high quality, sensitive, accessible maternity care.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that the participants were identified through connections with disability-related organizations, or other indications of experience caring for women with physical disabilities (such as a practice website). Other health care practitioners who provide care to women with physical disabilities may not have been identifiable through these methods and therefore their views are not represented in this study. In addition, though many participants spoke to their experiences with the maternity care system as a whole, health care practitioners were specifically identified for their experience caring for women with disabilities and so their perceptions may not reflect those of their colleagues with less experience caring for women with physical disabilities. The data presented represent practitioners’ own perceptions of issues caring for women with disabilities and has not been confirmed through observation or by having participants decide whether this stud is an accurate portrayal of their experiences, as is common in self-report and qualitative research.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study point to a need for systematic efforts to counteract the barriers to providing maternity care to women with physical disabilities encountered by healthcare practitioners at four levels: practitioner, clinical practice, system, and scientific evidence-related. The information from this study based on interviews with maternity care health care practitioners in concordance with the unmet needs and barriers to perinatal care from the perspective of women with physical disabilities offer a foundation for the development of interventions, programs, policies and clinical guidelines aimed at overcoming these barriers, and improving the quality of maternity care to women with physical disabilities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mitra M, Long-Bellil LM, Iezzoni LI, et al. Pregnancy among women with physical disabilities: Unmet needs and recommendations on navigating pregnancy. Disabil Health J. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smeltzer SC, Mitra M, Iezzoni LI, Long-Bellil L, Smith LD. Perinatal experiences of women with physical disabilities and their recommendations for health care professional s. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.07.007. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iezzoni LI, Wint AJ, Smeltzer SC, et al. Effects of disability on pregnancy experiences among women with impaired mobility. Acta Obstet et Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:133–140. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malouf R, Redshaw M, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. Systematic review of heath care interventions to improve outcomes for women with disability and their family during pregnancy, birth and postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-58. 58-2393-14-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redshaw M, Malouf R, Gao H, et al. Women with disability: the experience of maternity care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipson JG, Rogers JG. Pregnancy, birth, and disability: women’s health care experiences. Health Care Women Int. 2000;21:11–26. doi: 10.1080/073993300245375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begley C, Higgins A, Lalor J, et al. Women with disabilities: barriers and facilitators to accessing services during pregnancy, childbirth and early motherhood. National Disability Authority; Dublin: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nosek MA, Young ME, Rintala DH, et al. Barriers to reproductive health maintenance among women with physical disabilities. Womens Health. 1995;4:505–518. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drainoni ML, Lee-Hood E, Tobias C, et al. Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2006;17:101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macfarlane A, O’Reilly-de Brun M. Using a theory-driven conceptual framework in qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:607–618. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson J, Dreyfus D, Cerreto M, et al. “Sometimes I feel overwhelmed”: educational needs of family physicians caring for people with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50:243–250. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tervo RC, Azuma S, Palmer G, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward persons with disability: a comparative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1537–1542. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robey KL, Minihan PM, Long-Bellil LM, et al. Teaching health care students about disability within a cultural competency context. Disabil Health J. 2013;6:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh KK, Hammerman S, Josephson F, et al. Caring for people with developmental disabilities: survey of nurses about their education and experience. Ment Retard. 2000;38:33–41. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0033:CFPWDD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smeltzer SC, Dolen MA, Robinson-Smith G, et al. Integration of disability-related content in nursing curricula. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2005;26:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell FK. Medical education and disability studies. J Med Humanit. 2009;30:221–235. doi: 10.1007/s10912-009-9088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty M, Finucane P, Ahern M. Teaching medical students about disability and rehabilitation: methods and student feedback. Med Educ. 2000;34:659–664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller SR. Fostering informed empathy through patient-centred education about persons with disabilities. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:196–199. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennison RH, Towson J. Training those who treat disabilities. Risk & Insurance. 2009;20:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stolzmann KL, Meterko M, Shwartz M, et al. Accounting for variation in technical quality and patient satisfaction: the contribution of patient, provider, team, and medical center. Med Care. 2010;48:676–682. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall W, Tucker CM, Roncoroni J, et al. Patients’ perceived cultural sensitivity of health care office staff and its association with patients’ health care satisfaction and treatment adherence. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1586–1598. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss R. Physicians’ office staff influence patient choice and satisfaction. Health Prog. 2001;82:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vornholt K, Uitdewilligen S, Nijhuis FJ. Factors affecting the acceptance of people with disabilities at work: a literature review. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23:463–475. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen CM, Bates K, Frechette AH, et al. Nothing about us without us: Including people with disabilities as teaching partners in university courses. International Journal of Whole Schooling. 2011;7:109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harriott EM, Williams TV, Peterson MR. Childbearing in U.S. military hospitals: dimensions of care affecting women’s perceptions of quality and satisfaction. Birth. 2005;32:4–10. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macpherson I, Roque-Sanchez MV, Legget Bn FO, et al. A systematic review of the relationship factor between women and health professionals within the multivariant analysis of maternal satisfaction. Midwifery. 2016;41:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]