Background

Sphenopalatine ganglion acupuncture was first used for the treatment of rhinitis in the 1960s, and has been widely practised in China since the 1970s.1 2 In recent years, this technique has been reported to be effective for rhinitis in clinical practice.3–5 However, it is challenging to reach the sphenopalatine ganglion with an acupuncture needle. Additionally, the diameters of the arteries in the pterygopalatine fossa are large, and it is possible that the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery could be pierced. In the clinic, it is common for patients to present with lower eyelid bruising the day after treatment, but it is not clear whether this is caused by injury to this vessel.

Therefore, we performed a preliminary cadaveric study with the following aims: (1) to define the feasibility of an acupuncture needle reaching the sphenopalatine ganglion without prior exposure of the ganglion; and (2) to additionally consider the potential relationship between lower eyelid bruising on the day after treatment and piercing of the maxillary artery.

Methods

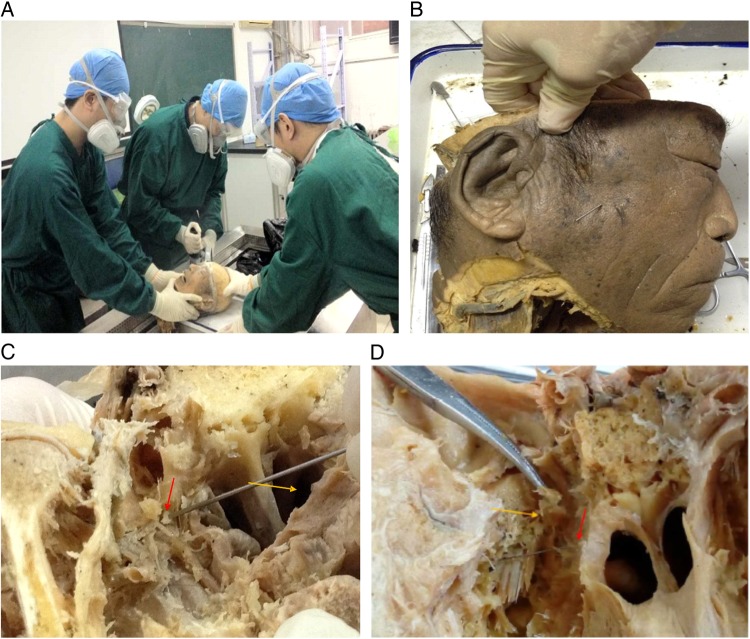

Six adult male wet-preserved skulls (a total of 12 sides) were used in this study. The procedure was divided into three steps. Firstly, we removed the brains from the skulls (figure 1A). Secondly, we inserted an acupuncture needle into the pterygopalatine fossa (figure 1B). Thirdly, we exposed the sphenopalatine ganglion and identified the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery (figure 1C, D).

Figure 1.

(A) Craniotomy and brain removal. (B) A wet-preserved scull, showing the position of the acupuncture needle. (C) Exposure of the pterygopalatine fossa and sphenopalatine ganglion. After removing tissues along the petrous bone, the pterygoid body was removed to expose the pterygopalatine fossa from behind. The red arrow indicates the sphenopalatine ganglion. The yellow arrow indicates the choanae (marked here to indicate the direction). (D) Acupuncture needle touching the sphenopalatine ganglion (indicated by the red arrow). The yellow arrow indicates lifting of the branches of the trigeminal nerve.

During the second step, the physician inserted a 0.35 mm×60 mm stainless steel needle (Zhongyan Taihe) vertically into the temporal fossa, under the zygomatic arch, behind the mandibular coronoid. The overall direction of the procedure was inwards, forwards and upwards (figure 1B), as it would be performed in live patients. Given that the pterygomaxillary fissure is a narrow slit and varies among individuals, the needle was retracted for repositioning if significant resistance was experienced before reaching a depth of 50 mm. The needle was then reinserted following adjustment. Upon reaching a depth of about 50 mm, the needle was inserted further until resistance was detected. If no resistance was detected, the needle was inserted fully (60 mm).

In the third step, in order to expose the pterygopalatine fossa, all structures behind the petrous bone were dissected away, while keeping the trigeminal ganglion in situ. Soft tissues were removed from the back to the front (including the pterygoid muscles, etc). To expose the entire pterygopalatine fossa from the rear, the pterygoid body and the lateral and medial pterygoid plates of the sphenoid bone were removed.

Findings

The average needle insertion depth was 55.9±1.87 mm on the left side and 55.3±1.59 mm on the right side. The needle only touched the sphenopalatine ganglion in two of 12 insertions (once on the left and once on the right). For the remaining 10 cases, the distance between the needle and the sphenopalatine ganglion ranged between 5.7 and 10.0 mm on the left and 2.9 and 15.5 mm on the right. The needle made contact with the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery in four of six insertions (67%) on the left and three of six insertions (50%) on the right.

Comment

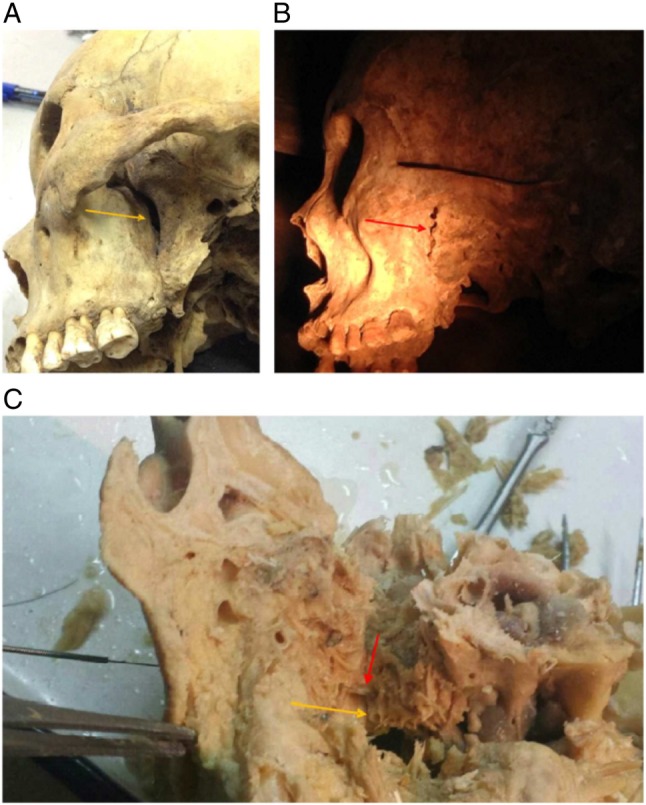

As the sphenopalatine ganglion is relatively small and varies in size between individuals, and given our observations in this study, we believe that inserting the acupuncture needle into the pterygopalatine fossa through the temporal fossa is feasible, when there is no variability in that fossa (figure 2A, B), but that it is actually difficult to reach the sphenopalatine ganglion without visual observation. Previous clinical studies have reported that needles can easily be inserted to touch the sphenopalatine ganglion; however, in this anatomical study, the needle only touched the sphenopalatine ganglion in two of 12 insertions (17%).

Figure 2.

(A) Funnel-shaped morphology of the adult pterygomaxillary fissure.The yellow arrow indicates a funnel-shaped adult pterygomaxillary fissure. (B) Jagged morphology of the pterygomaxillary fissure that could affect the acupuncture procedure. The red arrow indicates the jagged adult pterygomaxillary fissure. (C) Needle approaching the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery The red arrow indicates the needle approaching the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery; the yellow arrow indicates the lumen of the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery.

The adverse side effect of lower eyelid bruising on the day after the procedure might be attributable to the piercing of the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery or a branch thereof. The arterial lumen was visible with the naked eye in our study. Out of the 12 needle insertions, the needle tip was found to lie adjacent to the artery on seven occasions (figure 2C), that is, a probability of 58%.

Follow-up

Owing to the small number of specimens dissected and the difficulty of obtaining cadavers, we intend to conduct this study in a larger number of specimens to further verify our findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: LZ and D-LF contributed equally. All the authors conceived the study, approved the final manuscript and agreed to its submission for publication.

Funding: The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central public welfare research institutes (grant no. ZZ070852).

Competing interests: None declared.

Subject consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Li X, Tian P. New treatment for rhinitis—a preliminary summary of using acupuncture on the sphenopalatine ganglion. Beijing J Chin Med 1990;4:36–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X. Acupuncture on the sphenopalatine ganglion—“nose treatment 3” the mechanistic analysis of using acupuncture for the treatment of nasal diseases and introduction of acupuncture techniques. Clin J Otorhinolaryngol 2011;3:193. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Lai X, Zhuang L, et al. Electric acupuncture on the sphenopalatine ganglion to treat perennial allergic rhinitis—an observation study based on 50 clinical cases. New Chin Med 2007;39:51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu J, Tai H, Jing Q. “Xiaguan” point acupuncture of the sphenopalatine ganglion in the treatment of 20 cases of allergic rhinitis. J Gansu Coll Tradit Chin Med 2000;17:30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L. Using acupuncture on the sphenopalatine ganglion and integrated microwave in the treatment of 60 cases of allergic rhinitis. Lab Clin Med 2012;9:500–1. [Google Scholar]