Abstract

Background

Evidence for treating infantile colic with acupuncture is contradictory.

Aim

To evaluate and compare the effect of two types of acupuncture versus no acupuncture in infants with colic in public child health centres (CHCs).

Methods

A multicentre, randomised controlled, single-blind, three-armed trial (ACU-COL) comparing two styles of acupuncture with no acupuncture, as an adjunct to standard care, was conducted. Among 426 infants whose parents sought help for colic and registered their child's fussing/crying in a diary, 157 fulfilled the criteria for colic and 147 started the intervention. All infants received usual care plus four extra visits to CHCs with advice/support (twice a week for 2 weeks), comprising gold standard care. The infants were randomly allocated to three groups: (A) standardised minimal acupuncture at LI4; (B) semi-standardised individual acupuncture inspired by Traditional Chinese Medicine; and (C) no acupuncture. The CHC nurses and parents were blinded. Acupuncture was given by nurses with extensive experience of acupuncture.

Results

The effect of the two types of acupuncture was similar and both were superior to gold standard care alone. Relative to baseline, there was a greater relative reduction in time spent crying and colicky crying by the second intervention week (p=0.050) and follow-up period (p=0.031), respectively, in infants receiving either type of acupuncture. More infants receiving acupuncture cried <3 hours/day, and thereby no longer fulfilled criteria for colic, in the first (p=0.040) and second (p=0.006) intervention weeks. No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

Acupuncture appears to reduce crying in infants with colic safely.

Trial registration number

NCT01761331; Results.

Keywords: ACUPUNCTURE, PAEDIATRICS

Introduction

Excessive crying in infants is a problem for 10–20% of families, causing pain in the infant and stress in the family.1 2 If crying and/or fussing exceeds 3 hours/day for >3 days/week, it is defined as infantile colic.3 The colic may be resolved if cow's milk protein is eliminated.4 Nutritional supplements of Lactobacillus reuteri might also be effective.5 However, the effectiveness and safety of other conventional treatments remains unproven.

Standardised acupuncture grounded in neurophysiology is a Western approach, while the hypothesis in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is that the effect of acupuncture depends on which points are used. While some argue that needling sensation (de qi) is necessary, others have demonstrated beneficial effects with minimal stimulation. There is a need for further research to compare standardised and individualised treatment, as well as to determine the optimal stimulation parameters and treatment intervals.6

It is plausible that acupuncture may have positive effects in infantile colic as it is recognised to reduce pain, restore gastrointestinal function and have a calming effect.7 No serious side effects have been reported to date.8–11

Acupuncture is sometimes used to treat infantile colic, despite sparse and conflicting evidence.12 Until now, only three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of acupuncture for infantile colic have been published.8 10 11 Of these, the first two trials8 11 reported a significant reduction in crying following minimal acupuncture (MA) at LI4 compared to no acupuncture. The first trial8 involved bilateral needling at LI4 for 20 s, while the second11 applied unilateral needling at LI4 for only 2 s. By contrast, the third trial10 evaluated the effect of 30 s of acupuncture at ST36 bilaterally, and found no significant difference between the groups at the end of the follow-up (FU) period. In all three studies, the treatment was short in duration and standardised in nature (using a single point) and, therefore, arguably does not reflect clinical practice. Most acupuncturists sharing their experiences in a previous survey12 reported using more than one point when treating infantile colic, tailoring each treatment to match the infant's current symptoms as reported by the parents. LI4 and ST36, both considered important in the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms7 13 and infantile colic,12 were among the most commonly used traditional acupuncture points. In addition, Sifeng is classically indicated for impaired digestion in childhood13 and is considered to provide a stronger stimulus while also being more painful.12

Furthermore, the three previous studies8 10 11 were conducted in private clinics where parents may have relied strongly on the intervention. We believe that, if acupuncture is found to be safe and effective in infants with colic, it should be offered as standard treatment. In Sweden, this means that acupuncture would need to be implemented as a part of the public health care system at child health centres (CHCs), as only healthcare professionals (such as nurses and physicians authorised by the National Board of Health and Welfare) are allowed to treat children by law. Therefore, the original aims of this trial were: (1) to test if acupuncture is effective as a treatment for infantile colic in a CHC setting; and (2) to compare the effect of two types of acupuncture against no acupuncture in infants with colic at CHCs.

Methods

Design

We performed a multicentre three-armed RCT (ACU-COL) to compare two styles of acupuncture as an adjunct to gold standard care with gold standard care alone (no acupuncture) in infants with colic. The study was conducted at four CHCs in Sweden, which comprised two centres located close to the second and third biggest cities in Sweden, and two in smaller cities. Alongside usual care at their regular CHCs, recruited infants visited a study CHC twice a week for 2 weeks. Infants were randomly allocated to one of three groups: group A received standardised MA at LI4; group B received semi-standardised individualised acupuncture inspired by TCM; and group C received no acupuncture. The CHC nurse and the parents were blinded to group allocation.

Participants

Eligible infants were those who, according to their parents' records in a diary, cried and/or fussed >3 hours/day for >3 days during the baseline week (BL). In addition to fulfilling these criteria for colic, infants needed to be between 2 and 8 weeks of age and otherwise healthy with appropriate weight gain. Before inclusion they also needed to have tried a diet excluding cow's milk protein from breastfeeding mothers and/or appropriate formula for at least 5 days. The exclusion criteria included being born before 37 weeks’ gestation, taking any kind of prescribed medication or having previously tried acupuncture.

Acupuncturists' backgrounds

In total 10 acupuncturists participated in this study, five of whom performed the absolute majority of the treatments; the rest were sporadic stand-ins. Nine were registered nurses and midwives, and one stand-in was a medical doctor. Nine had undergone extensive acupuncture training including TCM, while one had relatively less training. They had been in private acupuncture practice for a mean duration of 20 years (range 1–30 years). Each acupuncturist attended an education day on acupuncture for colic and study procedures.

Participant enrolment

Parents seeking help for colic were informed of the trial by nurses at their ordinary CHC and through a website. Parents were informed that the trial compared two types of acupuncture versus no acupuncture. Those who wanted to participate contacted the project leader (KL) and started to register their infant's crying in a diary. If the infant fulfilled the criteria for colic (as above), he/she was included.

Data collection

Parents registered the infant's fussing and crying daily in a detailed diary during the BL, the first intervention week (IW1), the second IW (IW2) and the FU period that concluded with a phone interview 3 days after completion of IW2 (6 days after the final visit). At the first visit, the nurse collected informed consent and background data. At each of the following visits (and by phone for FU), parents were asked questions about changes in their infant's crying, stooling and sleep, and any side effects they associated with acupuncture. A more detailed description of the methods is provided in the study protocol.14 Data were collected between January 2013 and May 2015.

Usual care

Parallel to the intervention, all infants followed the national, free-of-charge programme at their regular CHC, which included seven visits during the first 3 months. At these visits, parents received routine childcare advice and infants were weighed and measured.

Interventions

Parallel to usual care, study participants visited the study CHC twice a week for 2 weeks. Thus, all infants received usual care plus four extra visits to a CHC, during which parents met a nurse for 20–30 min and were able to discuss their infant's symptoms. Together these were considered to represent gold standard care. The nurse listened, and gave evidence-based advice and calming reassurance. Breastfeeding mothers were encouraged to continue breastfeeding. At each visit, the study nurse carried the infant to a separate treatment room where they were left alone with the acupuncturist for 5 min. The acupuncturist treated the baby according to group allocation and recorded the treatment procedures and any adverse events. Disposable stainless steel 0.20×13 mm Vinco needles (Helio, Jiangsu Province, China) were used.

Infants allocated to group A received standardised MA at LI4. One needle was inserted to a depth of approximately 3 mm unilaterally for 2–5 s and then withdrawn without stimulation. Infants allocated to group B received semi-standardised individualised acupuncture, mimicking clinical TCM practice.12 Following a manual, the acupuncturists were able to choose one point, or any combination of Sifeng, LI4 and ST36, depending on the infant's symptoms, as reported in the diary. A maximum of five insertions were allowed per treatment. Needling at Sifeng consisted of four insertions, each to a depth of approximately 1 mm for 1 s. At LI4 and ST36, needles were inserted to a depth of approximately 3 mm, uni- or bilaterally. Needles could be retained for 30 s. De qi was not sought, therefore stimulation was similarly minimal in groups A and B. Infants in group C spent 5 min alone with the acupuncturist without receiving acupuncture.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the relative difference in mean values of total crying (TC) time, that is, the sum of the times spent fussing, crying and colicky crying, between BL and IW2, recorded in minutes. The secondary outcome was the number of infants in each group who continued to fulfil the criteria for colic at the end of each IW. Adverse events and the success of parental blinding were additionally reported.

Sample size

According to a power analysis based on the results of an earlier trial,11 it was estimated that 192 infants would be needed to detect a clinically relevant difference in crying of 30 min/day between the two acupuncture groups (11% reduction in IW1/IW2 relative to the BL week). Unfortunately, recruitment to the trial unexpectedly stopped when acupuncture became available without randomisation, before such time as a sufficient number of infants had been recruited to test the original hypothesis. Accordingly, a further power calculation was conducted in order to determine whether a sufficient number of participants had been recruited to be able to detect a significant difference between those infants receiving (any) acupuncture (groups A and B combined) and those not receiving acupuncture (group C); the sample size required was 144 infants (for 80% power) equally distributed across the groups.

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated into one of the three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio, according to randomisation lists generated by R&D, Region Skane. As infants were randomised into two strata (ages 2–5 and 6–9 weeks, respectively), two randomisation lists were created for each study centre. Participants were assigned to the three different groups by sampling without replacement. When the project leader had included an infant, the project coordinator in charge of the randomisation was informed. She sent the study number to the nurse at the study CHC via email, and also revealed the study number and allocation to the acupuncturist.

Blinding

Only the project coordinator (who had no contact with the CHC) and the acupuncturists knew which group each infant had been randomised to. The nurse was blinded to group allocation, as were the parents until they had answered the questions at the end of the FU period. The acupuncturists had no contact at all with the parents, and no contact with the nurses except for a short report when the baby and the diary were transferred to and from the treatment room. Blinding was measured by asking the parents four times if they believed their infant had received acupuncture or not.14 If both parents were present and had differing opinions, the option ‘don't know’ was marked.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using the data collected in forms and records. Descriptive statistics are presented as n (%), median [IQR] or median (range). Differences between groups were assessed by the Fisher's exact test, Mann-Whitney U test or the Kruskal-Wallis H test as appropriate. All data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.22 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A two-sided p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Conducting research with children always requires careful ethical reflection, as discussed in the study protocol.14 All parents received verbal and written information before signing informed consent. The Regional Ethical Review Board approved this study (Dnr 2012/620).

Results

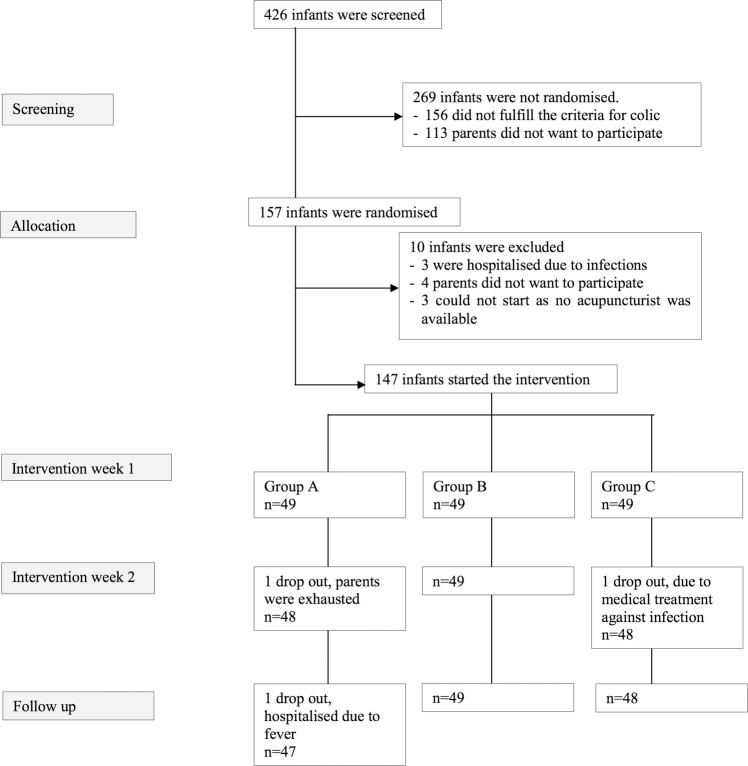

Of 426 infants screened for eligibility, 157 infants fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were randomised (figure 1). Of these, 147 infants started the intervention and were treated according to the randomisation schedule. One hundred and forty-four infants completed the study period. There were no differences between groups for background data. Background data for the included infants are reported in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the ACU-COL study. Group A received standardised minimal acupuncture at LI4. Group B received semi-standardised individualised acupuncture at LI4, ST36 and/or Sifeng. Group C received no acupuncture. All groups also received gold standard care, which comprised seven routine visits and four extra visits to a community health centre.

Table 1.

Background data for participating infants

| Group A n=49 |

Group B n=49 |

Group A+B n=98 |

Group C n=49 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 26 (53) | 20 (41) | 46 (47) | 21 (43) |

| Age at colic onset (weeks), median [IQR] | 2.0 [1.0–2.0] | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] | 2.0 [1.0–2.0] | 2.0 [1.0–3.0] |

| Age at inclusion (weeks), median [IQR] | 6.0 [4.5–6] | 6.0 [4.5–7] | 6.0 [4.8–7.0] | 6.0 [5.0–7.0] |

| Solely breastfed, n (%) | 31 (63) | 30 (61) | 61 (62) | 24 (49) |

There were no significant differences between groups A and B for any of the study's outcome measures, consistent with the relative lack of power due to recruitment ending prematurely. Accordingly, all outcome data are additionally presented as two groups (groups A and B combined vs group C) to reflect the overall effects of acupuncture.

Crying

The effect of the two types of acupuncture was similar and both groups receiving acupuncture (A and B) showed improvements over gold standard care alone (group C). Compared with infants not receiving acupuncture, those in the acupuncture groups exhibited a significant relative reduction in the time spent crying between BL and IW2 (p=0.05), and in the time spent colicky crying between BL and FU (p=0.031; table 2). When the acupuncture groups were merged the same end points were significant (p=0.021 and 0.031, respectively). As shown in table 3, when comparing the absolute differences between the merged groups, duration of colicky crying was reduced at FU (p=0.028) for infants receiving any acupuncture and TC was reduced at both IW1 and IW2 (p=0.032 and p=0.020, respectively). It should be noted that parents of seven infants (four in group A, two in group B, and one in group C) had recorded all crying as ‘crying’ without differentiating between ‘fussing’, ‘crying’ or ‘colicky crying’ in the diaries during BL. After clarification of the instructions, these parents began to classify crying into those three subcategories from IW1 onwards. In the absence of baseline data for these infants, time spent fussing and colicky crying were considered to represent missing data at IW1, IW2 and FU (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Relative differences in total crying duration and time spent fussing, crying and colicky crying

| Relative difference (%) by Kruskal-Wallis H test |

Relative difference (%) by Mann-Whitney U test |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL—IW1 |

|||||||

| A | B | C | A+B | C | |||

| n=49 | n=49 | n=49 | p Value | n=98 | n=49 | p Value | |

| Fussing | 20 (−102–70)* | 24 (−41–100)† | 11 (−100–85)‡ | 0.202 | 23 (−102–100)§ | 11 (−100–85)‡ | 0.089 |

| Crying | 23 (−6950–83) | 29 (−132–82) | 18 (−347–84) | 0.478 | 27 (−6950–83) | 18 (−347–84) | 0.233 |

| Colicky crying | 60 (−158–100)* | 52 (−431–100)† | 43 (−227–100)‡ | 0.647 | 53 (−431–100)§ | 43 (−227–100)‡ | 0.427 |

| TC | 27 (−83–65) | 25 (−29–68) | 22 (−26–57) | 0.211 | 27 (−83–68) | 22 (−26–57) | 0.081 |

| BL—IW2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | p Value | A+B | C | p Value | |

| n=48 | n=49 | n=48 | n=97 | n=48 | |||

| Fussing | 35 (−116–83)* | 30 (−156–87)† | 28 (−177–89)† | 0.733 | 34 (−156–87)§ | 28 (−177–89)† | 0.515 |

| Crying | 39 (−7550–91) | 41 (−104–89) | 22 (−90–97) | 0.050 | 40 (−7550–91) | 22 (−90–97) | 0.021 |

| Colicky crying | 69 (−157–100)* | 81 (−37–100)† | 71 (−71–100)† | 0.361 | 75 (−157–100)§ | 71 (−71–100)† | 0.400 |

| TC | 38 (−57–77) | 44 (−18–87) | 33 (−7–88) | 0.151 | 41 (−57–87) | 33 (−7–88) | 0.068 |

| BL—FU |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | p Value | A+B | C | p Value | |

| n=47 | n=49 | n=48 | n=96 | n=48 | |||

| Fussing | 35 (−96–96)¶ | 34 (−150–97)† | 27 (−100–93)† | 0.591 | 35 (−150–97)** | 27 (−100–93)† | 0.349 |

| Crying | 42 (−12 150–100) | 56 (−305–97) | 35 (−109–100) | 0.237 | 47 (−12 150 –100) | 35 (−109–100) | 0.202 |

| Colicky crying | 89 (−161–100)¶ | 96 (−140–100)† | 65 (−294–100)† | 0.031 | 92 (−161–100)** | 65 (−294–100)† | 0.031 |

| TC | 47 (−90–97) | 50 (−22–92) | 32 (−66–98) | 0.142 | 49 (−90–97) | 32 (−66–98) | 0.067 |

Statistically significant p values (p≤0.05) are indicated by bold text. P values representing a statistical tendency towards significance (p=0.051–0.1) are italicised.

Data are presented as median (range).

*n=45.

†n=47.

‡n=48.

§n=92.

¶n=43.

**n=90.

BL, baseline; FU, follow-up; IW, intervention week; TC, total crying.

Table 3.

Absolute differences in total crying duration and time spent fussing, crying and colicky crying (minutes/day)

| BL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | A+B | C | |||

| n=49 | n=49 | n=49 | p Value | n=98 | n=49 | p Value | |

| Fussing | 107 [76–143] | 116 [86–181] | 107 [76–174] | 0.460 | 110 [81–158] | 107 [76–174] | 0.829 |

| Crying | 74 [48–104] | 88 [57–112] | 86 [49–111] | 0.169 | 80 [53–110] | 86 [49–111] | 0.971 |

| Colicky crying | 36 [18–89] | 46 [15–93] | 55 [22–101] | 0.517 | 42 [17–92] | 55 [22–101] | 0.272 |

| TC | 234 [178–293] | 270 [211–331] | 262 [214–336] | 0.061 | 252 [204–311] | 262 [214–336] | 0.355 |

| IW1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | p Value | A+B | C | p Value | |

| n=49 | n=49 | n=49 | n=98 | n=49 | |||

| Fussing | 78 [56–114]* | 86 [56–164]† | 96 [66–152]‡ | 0.270 | 80 [56–138]§ | 96 [66–152]‡ | 0.160 |

| Crying | 59 [32–83] | 59 [47–88] | 59 [45–95] | 0.636 | 59 [38–83] | 59 [45–95] | 0.612 |

| Colicky crying | 15 [2–43]* | 18 [6–37]† | 26 [9–51]‡ | 0.268 | 18 [4–40]§ | 26 [9–51]‡ | 0.115 |

| TC | 157 [128–235] | 192 [134–247] | 206 [153–270] | 0.046 | 170 [132–246] | 206 [153–270] | 0.032 |

| IW2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | p Value | A+B | C | p Value | |

| n=48 | n=49 | n=48 | n=97 | n=48 | |||

| Fussing | 72 [49–95]* | 87 [44–145]† | 85 [50–131]† | 0.231 | 76 [48–106]¶ | 85 [50–131]† | 0.355 |

| Crying | 42 [25–70] | 44 [28–70] | 56 [32–82] | 0.268 | 44 [26–69] | 56 [32–82] | 0.105 |

| Colicky crying | 9 [2–36]* | 8 [2–26]† | 13 [4–36]† | 0.513 | 9 [2–32]¶ | 13 [4–36]† | 0.331 |

| TC | 136 [104–178] | 139 [96–225] | 176 [133–223] | 0.051 | 137 [101–200] | 176 [133–223] | 0.020 |

| FU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | p Value | A+B | C | p Value | |

| n=47 | n=49 | n=48 | n=96 | n=48 | |||

| Fussing | 66 [41–98]** | 68 [42–127]† | 88 [45–133]† | 0.328 | 66 [41–100]†† | 88 [45–133]† | 0.173 |

| Crying | 43 [17–67] | 39 [26–60] | 42 [31–84] | 0.771 | 41 [22–66] | 42 [31–84] | 0.498 |

| Colicky crying | 3 [0–21]** | 0 [0–11]† | 13 [0–26]† | 0.055 | 3 [0–17]†† | 13 [0–26]† | 0.028 |

| TC | 115 [81–181] | 128 [87–214] | 164 [112–230] | 0.170 | 123 [87–197] | 164 [112–230] | 0.073 |

Statistically significant p values (p≤0.05) are indicated by bold text. P values representing a statistical tendency towards significance (p=0.051–0.1) are italicised.

Data are presented as median [IQR].

Kruskal-Wallis H test and Mann Whitney U test used.

*n=45.

†n=47.

‡n=48.

§n=94.

¶n=93.

**n=43.

††n=92.

BL, baseline week; FU, follow-up; IW, intervention week; TC, total crying.

Table 4 shows the main secondary outcome, namely the number of infants in each group who continued to fulfil the criteria for colic at the end of each IW. Significantly fewer infants who received acupuncture continued to cry/fuss excessively at the end of IW1 (p=0.040) and IW2 (p=0.006).

Table 4.

Infants continuing to cry and/or fuss for ≥3 hours/day ≥3 days/week

| Group |

Group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | A+B | C | |||

| n=49 | n=49 | n=49 | p Value* | n=98 | n=49 | p Value† | |

| IW1, n (%) | 26 (53.1) | 33 (67.3) | 38 (77.6) | 0.040 | 59 (60.2) | 38 (77.6) | 0.043 |

| IW2, n (%) | 16 (32.7) | 21 (42.9) | 31 (64.6) | 0.006 | 37 (37.8) | 31 (64.6) | 0.003 |

Statistically significant p values (p≤0.05) are indicated by bold text.

*Fisher's exact test.

†Mann Whitney U test.

IW, intervention week.

Blinding

On four occasions the parents answered the question ‘Do you think your infant received acupuncture?’ with ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don't know’. In group C, 21–29% of the parents guessed correctly (no acupuncture) on all four occasions, while the rest (71–79%) either thought that their infant had received acupuncture or didn't know (table 5). The percentage of parents in merged group A+B who correctly guessed that their infant had received acupuncture increased from 45% to 72% between the first and last occasions, while 28–55% were incorrect or didn't know.

Table 5.

Assessment of parental blinding

| Visit | Group | n | Guessed correctly n (%) |

Guessed incorrectly n (%) |

Didn't know n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second | A+B | 97 | 44 (45) | 13 (13) | 40 (41) |

| C | 49 | 12 (25) | 12 (25) | 23 (49) | |

| Third | A+B | 97 | 52 (54) | 18 (19) | 27 (28) |

| C | 48 | 10 (21) | 18 (37) | 20 (42) | |

| Fourth | A+B | 96 | 63 (66) | 11 (12) | 21 (22) |

| C | 48 | 14 (29) | 18 (38) | 16 (33) | |

| Follow-up* | A+B | 95 | 68 (72) | 10 (10) | 17 (18) |

| C | 48 | 10 (21) | 21 (44) | 17 (35) |

*Telephone call.

Adverse events

In total, 388 treatments were given. On 200 occasions the infant did not cry at all, on 157 occasions the infant cried up to 1 min, and on 31 occasions the infant cried for >1 min (mean 2.7 min). The acupuncturists reported bleeding (a single drop of blood) on 15 occasions. One parent reported seeing a drop of blood on the infant's clothes, and one reported seeing a mark on the infant's hand. No other adverse events were reported.

Discussion

In this present study of two types of acupuncture versus no acupuncture, crying and fussing were reduced in all groups. This was to be expected, as colic is a spontaneously healing condition. However, the magnitude of the reduction in crying was greater, suggesting a faster recovery, in infants who received either type of acupuncture compared to gold standard care alone. Fussing and crying are normal communications for a baby, therefore a reduction to normal levels (rather than silence) is the goal of treatment. Even though the reduction in minutes may seem modest, significantly more infants who received acupuncture cried for <3 hours/day, with significantly less time spent colicky crying, which is the most intense form of crying. This reduction in crying is arguably the difference between having a baby with colic versus one without, and therefore is clinically relevant for parents. Thus acupuncture might have a role in shortening the strenuous period of colic. It also appeared to be a safe treatment, in the setting of this RCT.

Another clinically relevant finding is that, out of the 426 infants screened for ACU-COL, only 157 were actually found to have persistence of colic after a 5-day period without cow's milk. During this time, a diary was used to measure the duration and intensity of crying, and parents were offered advice and support by telephone. Thus, the majority of infants in this cohort did not have colic, even though their parents sought help for excessive crying. These cheap, safe and effective interventions may have helped stressed parents assess the situation in a more objective way, and thereby have avoided unnecessary treatment.

Meeting a supportive professional may relieve the burden of colic for parents.1 Besides usual care, each family in the ACU-COL study had four extra visits to a CHC where they met a nurse specialised in paediatric care who asked questions, listened, and gave commendations, advice and hope. Thus we had no placebo group; group C received gold standard care only, while groups A and B additionally received acupuncture. Acupuncture therapy led to a further reduction in crying, commensurate with the results of Reinthal et al8 and Landgren et al.11 The negative finding of Skjeie et al10 seems to be the outlier, and may be due to the use of a different acupuncture point, different treatment interval and/or a non-validated symptom diary.

It is unknown whether an optimal or adequate dose of acupuncture was used. In adults, the patient's own perception of the needle stimulation, for example, the de qi sensation, affects the outcome of treatment.15 In ACU-COL, the acupuncture stimulation was so mild it could be defined as minimal in both acupuncture groups; de qi was not sought. Many infants did not cry or show any motor response to the stimulus, and sleeping infants rarely woke up. Thus there was probably a lack of sensory, affective and cognitive perception, and infants may not therefore have received an adequate treatment.

Compared to TCM acupuncture treatments in adults, in ACU-COL fewer needles were used, the treatment time was shorter, and the needle stimulation followed recommendations to be very mild.12 Yet acupuncture showed a significant effect on some variables, suggesting that MA can have a therapeutic effect. This finding lends further support to the recommendation that MA should not be used as a placebo for research.

Although the numbers are still relatively small, ACU-COL adds further to our current body of knowledge regarding the safety of treating infants with acupuncture. The low frequency of reported adverse events is in line with earlier reports.16 We consider that any risks were minimised by the use of well-educated acupuncturists and sterile needles, as well as the avoidance of acupuncture points on the thorax. Infants tolerated the treatment fairly well. In 52% of the treatments (200/388) the infant did not cry at all, and only 8% of the treatments (31 of 388) triggered crying that lasted ≥ 1 min. Thus, if the treatment reduces excessive crying, it may be considered ethically acceptable.

Strengths and limitations

To increase the internal validity, we used a study protocol and adhered to the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) guidelines for RCTs of acupuncture.17 We used definitive inclusion criteria, a detailed diary, adequate randomisation, an appropriate control, sufficient FU, appropriate statistical methods and well-trained acupuncturists. Furthermore, we had a low dropout rate. The nurse who met the parents was blinded and consistently gave the same advice, instilling the same amount of hope for all families.

As the intervention for group B was only semi-standardised, we have not offered a true TCM treatment. However, the points used are adequate according to clinical practice and textbooks.12 A guideline was developed after consultation with experienced acupuncturists, following the STRICTA recommendations.17 It was based on a survey including 23 paediatric acupuncture teachers and experienced practitioners representing both traditional and Western acupuncture from nine countries.12 As the difference between sham and verum acupuncture remains unclear, and acupuncture points and stimulation methods considered to constitute ‘sham’ might in fact be effective,18 no sham acupuncture group was included.

A definite limitation was our design comparing two types of MA. Recent studies19 have shown that very large numbers of patients are needed to detect differences between two active acupuncture interventions, which was confirmed by ACU-COL wherein both acupuncture groups had a similar effect. An advantage is that this three-armed study included a group that did not get acupuncture. Unfortunately we could not reach the desired number of infants as recruitment ceased when acupuncture for colic became available at several clinics without the need for randomisation during the second year of data collection. To increase the statistical power, the two acupuncture groups were merged to evaluate the difference between (any) acupuncture and no acupuncture. These calculations, although post hoc, lend support to a potential therapeutic effect for acupuncture in colic.

When doing research on children, the results may be affected by parents' expectations, as the parents interpret and evaluate the child's symptoms.20 As parents in ACU-COL were blinded, the research strategy was not to explore the effect of acupuncture pragmatically as an adjunct to usual care, but rather to investigate whether acupuncture had an effect when parental expectancy was controlled for. Thus blinding was crucial and measured. Parents were unable to detect marks on their infant's skin after receiving acupuncture in an earlier study11 as well as in the present trial. Nonetheless, among parents of infants who received acupuncture, the percentage of those who believed that the infant had received acupuncture increased at the later visits. This probably reflects the fact that infants receiving acupuncture were deriving greater benefit from treatment.

Infants were not aware of the therapeutic relationship or possible benefits of acupuncture, both important components of the therapy that may be synergistic to the needle effect.15 As infants in ACU-COL were less influenced by the widely discussed placebo response, the positive results are even more interesting and add to our knowledge base, since the parents who carefully documented the infants' behaviour 24 hours/day were blinded to allocation.

Conclusion

Among those initially experiencing excessive infant crying, the majority of parents reported normal values once the infant's crying had been evaluated in a diary and a diet free of cow's milk had been introduced. Therefore, objective measurement of crying and exclusion of cow's milk protein are recommended as first steps, to avoid unnecessary treatment. For those infants that continue to cry >3 hours/day, acupuncture may be an effective treatment option. The two styles of MA tested in ACU-COL had similar effects; both reduced crying in infants with colic and had no serious side effects. However, there is a need for further research to find the optimal needling locations, stimulation and treatment intervals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ekhagastiftelsen and the family Uddenäs.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL and IH designed the trial and drafted the manuscript together. KL is the primary investigator and project leader.

Funding: Ekhagastiftelsen, Family Uddenäs.

Competing interests: None declared.

Parental consent: obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Landgren K, Hallström I. Parents’ experience of living with a baby with infantile colic—a phenomenological hermeneutic study. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25:317–24. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landgren K, Lundqvist A, Hallström I. Remembering the chaos—but life went on and the wound healed. A four year follow up with parents having had a baby with infantile colic. Open Nurs J 2012;6:53–61. 10.2174/1874434601206010053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James SR, Nelson KA, Ashwill JW. Nursing care of children. Principles and practice. St Louis: Saunders, Elsevier/Saunders, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacovou M, Ralston RA, Muir J, et al. Dietary management of infantile colic: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:1319–31. 10.1007/s10995-011-0842-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung V, Collett S, de Gooyer, et al. Probiotics to prevent or treat excessive infant crying: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:1150–7. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White A. Western medical acupuncture: a definition. Acupunct Med 2009;27:33–5. 10.1136/aim.2008.000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi T. Effect and mechanism of acupuncture on gastrointestinal diseases. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013;111:273–94. 10.1016/B978-0-12-411545-3.00014-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinthal M, Andersson S, Gustafsson M, et al. Effects of minimal acupuncture in children with infantile colic—a prospective, quasi-randomised single blind controlled trial. Acupunct Med 2008;26:171–82. 10.1136/aim.26.3.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinthal M, Lund I, Ullman D, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of infantile colic and their change after light needling of acupuncture: a case series study of 913 infants. Chin Med 2011;6:28 10.1186/1749-8546-6-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skjeie H, Skonnord T, Fetveit A, et al. Acupuncture for infantile colic: a blinding-validated, randomized controlled multicentre trial in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 2013;31:190–6. 10.3109/02813432.2013.862915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landgren K, Kvorning N, Hallström I. Acupuncture reduces crying in infants with infantile colic: a randomised, controlled, blind clinical study. Acupunct Med 2010;28:174–9. 10.1136/aim.2010.002394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landgren K. Acupuncture in practice: investigating acupuncturists’ approach to treating infantile colic. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:456712 10.1155/2013/456712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deadman P, Al-Khafaji M, Baker K. A manual of acupuncture. Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landgren K, Tiberg I, Hallström I. Standardized minimal acupuncture, individualized acupuncture, and no acupuncture for infantile colic: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial—ACU-COL. BMC Complement Alternat Med 2015;15:325 10.1186/s12906-015-0850-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White A, Cummings M, Barlas P, et al. Defining an adequate dose of acupuncture using a neurophysiological approach—a narrative review of the literature. Acupunct Med 2008;26:111–20. 10.1136/aim.26.2.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang C, Hao Z, Zhang LL, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture in children: an overview of systematic reviews. Pediatr Res 2015;78:112–19. 10.1038/pr.2015.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. Acupunct Med 2010;28:83–93. 10.1136/aim.2009.001370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi EM, Jiang F, Longhurst JC. Point specificity in acupuncture. Chin Med 2012;7:4 10.1186/1749-8546-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacPherson H, Maschino AC, Lewith G, et al. Characteristics of acupuncture treatment associated with outcome: an individual patient meta-analysis of 17,922 patients with chronic pain in randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2013;8:e77438 10.1371/journal.pone.0077438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grelotti DJ, Kaptchuk TJ. Placebo by proxy. BMJ 2011;343:d4345 10.1136/bmj.d4345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]