Abstract

Clinical use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices has grown over the past 15 years from a niche concept to becoming standard of care for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). With the December 2016 Food and Drug Administration approval for diabetes treatment decisions directly from CGM values (nonadjunctive use) without finger-stick confirmation, the uptake and scope of CGM use will likely further expand. With this expansion, it is important to consider the role and impact of CGM technology in specific settings and high-risk populations, such as the young and the elderly. In pediatric patients, CGM concerns include limited body surface area, difficulty keeping sensors adhered, and the role of nonadjunctive use in the school setting. In older adults, Medicare did not, until very recently, cover CGM devices and as such, their use had been limited by lack of reimbursement. As CGM use will likely expand in clinical practice given the nonadjunctive indication, guidelines and recommendations for clinical practice are warranted. In this article, we discuss recent research on CGM use in the special populations of children and older adults and provide initial guidelines for nonadjunctive use in clinical practice.

Keywords: : Continuous glucose monitoring, Nonadjunctive use, Type 1 diabetes

CGM Introduction

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices have grown over the past 15 years from a niche concept to the standard of care for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). While traditional blood glucose monitoring (BGM) allowed for multiple, episodic snapshots of glycemia at various points in time, CGM data provide patients, caregivers, and medical providers with a 24-h “glycemic video” showing where glucose is, where it has been, and a prediction of where it may be going. In addition, many CGM systems now allow for digital remote monitoring, through which caregivers are able to view a patient's CGM tracing on their own smartphone and receive alerts based on individualized thresholds and trend parameters, a feature particularly useful in the pediatric population.1

Over the past 5 years, there has been substantial improvement in CGM performance leading to greater uptake and use in a broader spectrum of patients.2 Studies on early-generation CGM systems showed usage rates of about 5%–20% of patients with rates below 10% in the pediatric, adolescent, and young adult populations.3,4 More recent data from the T1D exchange (T1DX) have shown growth in CGM use from 17% to 25% of patients, with particularly large increases in use among preschool-aged and early school-aged children.5 CGM barriers include dislike of on-body devices, cost, and insurance coverage.6

With the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in December 2016 for management decisions that include insulin dosing from CGM values (nonadjunctive dosing), the scope and use of CGM will likely expand further as the benefit increases relative to burden.7 As CGM use expands, especially regarding nonadjunctive use, it is important to consider the role and impact of this technology in specific settings and high-risk populations. In this article, we will discuss the use of CGM in children and older adults as well as the concept of nonadjunctive CGM use for correction boluses without BGM across age groups.

CGM Use in the Pediatric Population

CGM in children presents a spectrum of potential challenges and benefits, which differ among various pediatric age groups. In young children, CGM use can be challenged by limited body surface area, due to insufficient subcutaneous tissue and flat areas in which to place the CGM sensor, especially when there is competition for space with insulin infusion sets or pods and the requisite need for the sensor and insulin delivery point to be separated by at least 3 inches. Parents of young children often note difficulty keeping the sensor adhered to the body for 7 days due to multiple factors such as high activity levels, frequent water immersion, or manipulation of the tape or sensor by the young child. Finally, many young children and their parents are apprehensive of pain with sensor insertion, a situation for which the anxiety may be greater than the actual discomfort of sensor placement. Benefits of CGM in younger children include the ability of parents to detect impending hypoglycemia, which is particularly beneficial among young children who are unable to express symptoms of hypoglycemia, as well as increased glucose information with a reduced number of painful finger sticks, and the ability of the parent to remotely monitor glycemia overnight, while the child is at day care, preschool, or grade school.

In teens, CGM presents a different set of challenges and benefits. The increased and constant availability of glycemic information, available on the teens' smartphone, presents a double-edged sword. Teens often feel overwhelmed and burned-out by their T1D and its care requirements; some may disengage from self-care and do not want constant reminders of their glucose levels with need for attention to diet and insulin administration. Other teens, more engaged with their self-care, may find the continuous glucose information beneficial as they can discretely look at their cell phone (a quite common practice among most teens) to see their glucose and trend information without having to prick their finger and use their BG meter in front of peers. Indeed, CGM may help teens more easily attend to self-care when with their peers as momentary sampling data have revealed that teens are more likely to check BG levels when they want to “fit in.”8 Remote monitoring can also present a challenge to teens as they transition from diabetes family management to greater self-care they may be less willing for their parents to be following their glucose values remotely. Alternatively, remote monitoring of CGM data by parents can provide an additional safety net for teens as parents can monitor for glucose extremes, with particular attention to hypoglycemia as teens spend more time away from home and begin driving. For remote monitoring to be used, teens must also remember to charge their mobile devices so that they do not lose data connectivity.

To evaluate the benefit of CGM in lowering hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and reducing hypoglycemia, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) sponsored a randomized, multicenter 6-month clinical trial comparing CGM with BGM in children, adolescents, and adults with T1D.9–13 Using early-generation CGM technology, this study showed that CGM compared with BGM resulted in a significant reduction in HbA1c of 0.53% in adults (25 years of age or older) without any increase in hypoglycemia, although there were no significant differences in HbA1c between CGM and BGM groups in adolescents/young adults (15–24 years old) or school age children (8–14 years old).10 Of note, 83% of adults in the CGM group used CGM ≥6 days per week, while only 30% of adolescents/young adults and 50% of the school-aged children used CGM consistently for ≥6 days per week for the 6-month study. Further analysis revealed that, independent of age, consistent and durable use of CGM ≥6 days per week predicted the HbA1c benefit.12,13

While early studies were unable to demonstrate consistent glycemic benefits in pediatric and adolescent patients with T1D, it is important to recognize that CGM studies conducted 5–10 years ago included early-generation devices with technological and human factor limitations. These studies also did not utilize newer glycemic metrics (e.g., % in target range and glycemic variability), which are gaining increased focus.14 In the last 5 years, there has been remarkable improvement in CGM device performance, demonstrated by the remarkable improvement in mean absolute relative difference (MARD) of CGM devices.15,16 For example, the Dexcom SEVEN PLUS (Dexcom, Inc.) had MARD values of 16%–19% in the target range and 20%–40% in the hypoglycemia range.17 With recent advancements in the newer CGM systems, using improved interstitial sensors and advanced system algorithms, MARD has improved to ≤10% in both pediatric and adult patients, helping to prompt the recent FDA approval for nonadjunctive use.16 The pediatric study demonstrated an improvement in MARD from 17% to 10% in comparison of the original Dexcom G4 Platinum CGM with the newer 505 algorithm.18 A recent survey of adolescent and adults with T1D in the United States reported insufficient accuracy as the most frequent reason for patients to dislike using CGM (in 28% of responses).19

CGM Use in Older Adults

The management of older adults with T1D, or for that matter those with long-term T2D requiring basal bolus insulin, presents challenges. Because of improved clinical care and outcomes involving complex insulin and monitoring regimens, patients with T1D are living longer,20 leading to a growing number of older adults with T1D.21 In addition, many patients with T1D present as adults, adding to these growing numbers.22 Older insulin-treated patients tend to have longer durations of diabetes and are thus more likely to have micro- and macrovascular complications and other comorbidities.21,23 Older patients also have increased risk for severe hypoglycemia (SH),24,25 with reduced capacity to detect and counter-regulate against SH.25 SH is particularly dangerous in older patients, due to its association with risks for falls with injury, myocardial infarcts, arrhythmias, temporary or permanent cognitive impairment, and death.21,26 Schütt et al. reported that patients with T1D >60 years old had nearly twice the incidence of SH compared to younger T1D patients27; the T1DX reported that patients >65 years old had a high rate of SH (0.168 episodes/patient-year).28

In recognition of the management challenges of T1D in older adults, The American Diabetes Association has recommended individualized but higher HbA1c and glycemic goals that vary according to comorbid status in older adults.23 However, T1DX data indicate that those with higher HbA1c values are not less prone to SH than those with lower values28; thus, higher glycemic goals are not sufficient to prevent SH in older adults. In contrast, consistent CGM use has been demonstrated to improve glycemic control and reduce SH in patients >65 years old,29 and the DiaMonD study, a prospective, randomized clinical trial of CGM compared with BGM in adults (including elderly adults) with T1D treated with multiple injection therapy, showed improved HbA1c with less hypoglycemia regardless of age.30 A recent survey of older adults using CGM reported better glycemic control with reduced hypoglycemia compared with those not using CGM.31 The ability to monitor real-time glucose data and receive alerts regarding hypoglycemic events can aid in the management of T1D in older adults for the patients as well as their caregivers. Thus, CGM is effective and valuable for older adults as well as younger patients. Nearly all commercial insurers in the United States cover CGM in patients with T1D under some circumstances,32 but many older patients have not had access to personal CGM because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had not provided coverage33 until very recently (January 2017) when CMS categorized CGM as durable medical equipment, potentially expanding coverage for CGM devices that can be used to make treatment decisions, so-called nonadjunctive use.34

Adjunctive and Nonadjunctive CGM Use

Personal real-time CGM was originally approved by the FDA for adjunctive use, meaning the glucose results needed to be verified by BGM before taking action. The reasoning was that BGM has been the most accurate method of determining ambient BG for treatment decisions as early-generation real-time CGM was not accurate enough for treatment decisions. However, the improved accuracy and reliability of CGM devices now approximate the accuracy range reported for BGM.16 An FDA Advisory Board heard public testimony on July 21, 2016, and recommended that the Dexcom G5 Mobile device be approved for nonadjunctive use, a recommendation accepted by FDA on December 20, 2016.7

It is worthwhile to review CGM use by healthcare providers, families, and patients. Before recent FDA approval for nonadjunctive CGM use, there was already nonadjunctive use of CGM data as clinicians often adjusted insulin dosing based on downloaded CGM data or in the ambulatory glucose profile or similar reports. These reports offered a means to review specific daily tracings of postmeal glycemic excursions, episodes of hypoglycemia, or responses to exercise or illness, without reference to BGM data. Another use of CGM data involved trending data, which reveals the rate and direction of glucose change, indicated by the direction and number of visible arrows, providing timely information to assist with treatment decisions.35 A survey of successful full-time adult CGM users (mean A1c 6.9%, with infrequent SH) reported large dosing alterations based on the direction and rate of glucose change.36

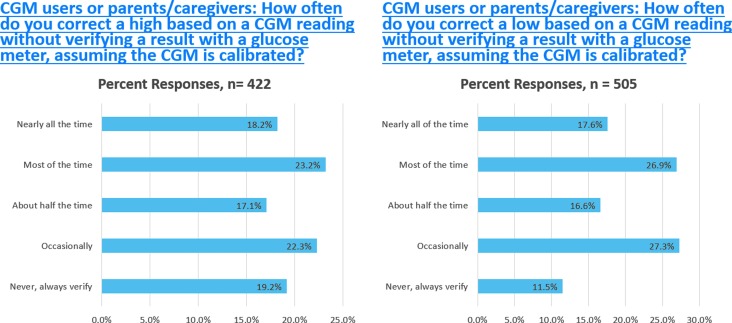

Many patients had been using CGM nonadjunctively, that is, basing their treatment decisions on the CGM glucose without BGM verification before the FDA ruling. Multiple studies have reported that CGM users performed BGM less frequently than non-CGM users.37–39 The T1DX reported a survey of 1613 CGM users, in which ∼50% reported performing BGM “less often” or “much less often” when using CGM.3 The results of a recent survey of T1D patients or parent/guardians of patients on myglu.org, the social media arm of the T1DX (Fig. 1), indicate that many are already using CGM nonadjunctively to treat hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Only 11.5% of patients or parent/caregivers reported that they always confirmed with BGM before treating hypoglycemia identified by CGM and only 19.2% reported they always confirmed hyperglycemia identified by CGM before treating.

FIG. 1.

myglu.org Surveys of Current CGM Users or Parent/Caregivers December 6, 2016, and December 8, 2016. CGM, continuous glucose monitoring.

Nonadjunctive Guidelines and Considerations

Despite the common practice of nonadjunctive CGM use to date, published reports and guidelines on this topic are modest.40–42 There are a number of important principles that should be followed for safe and effective nonadjunctive CGM use, pending the completion of formal clinical trials. These guidelines are as follows:

1. CGM must be calibrated as per the manufacturer's guidelines, until calibration-free CGM becomes available. CGM accuracy is only as good as the BGM data used for calibration. Fingertips must be clean, dry, and free from contaminating substances; BG strips should be properly stored and not expired.

2. CGM systems are generally less accurate, with higher MARDs on the first day of sensor insertion,18,43 indicating that day one values should be used with caution and may need confirmatory BGM.

3. Use of acetaminophen (APAP) may cause falsely high CGM glucose values with the current generation of real-time CGM devices available in the United States, and thus, APAP must be strictly avoided while using CGM, otherwise CGM values should be ignored for at least the duration of APAP action (4–8 h).44,45 In addition, patients and caregivers should be aware of combination “sinus, cold, and flu” medications, which may contain APAP.

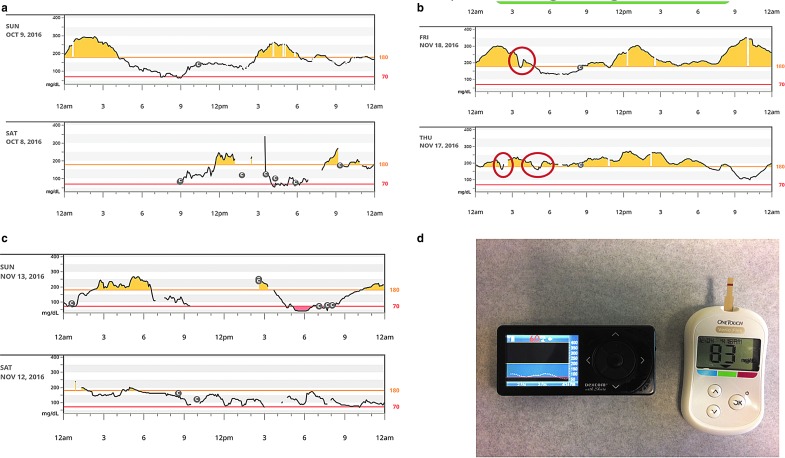

4. The quality of a CGM tracing needs to be evaluated to be certain that the result is credible. Tracings that change erratically should not be used without verification (e.g., Fig. 2). One common example of interference is a pressure-induced sensor attenuation or compression artifact, due to reduction in perfusion of the local tissue where the sensor is located, a problem that often causes false hypoglycemia alarms at night if a patient is sleeping on the sensor.46 It is important not to recalibrate the CGM following a low-glucose alert resulting from compression artifact.

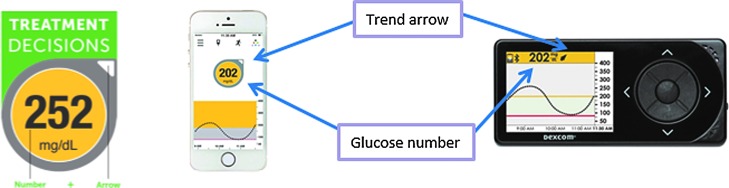

5. The CGM can be used for diabetes management (e.g., treating high or low glucose levels) as long as the receiver/phone screen displays both a glucose number and a directional arrow (showing the direction of the glucose change while the arrow's angle displays the glucose rate of change) (Fig. 3). If only a glucose number appears without an arrow, one should check a finger-stick BG to make management decisions until an arrow reappears. The lack of an arrow indicates that the CGM algorithm requires more time to ensure adequate CGM performance for management decisions.

6. The rate of change of glucose may be as important as is the actual glucose value in determining the optimal treatment. One conservative method is to extrapolate the rate of change, as indicated by change arrows, and project what the glucose will likely be in 30 min, and use that number as the number to correct or act upon.40 This technique may allow the ingestion of carbohydrate to prevent an impending hypoglycemic event, and a higher insulin correction dose, thereby reducing the extent of an upward excursion. A similar approach to dosing adjustments includes increasing or decreasing the dose by 10% or 20% based upon 1 or 2 arrows upward or downward, respectively (glucose changing by 1–2 mg/dL/min or >2 mg/dL/min, respectively).47

7. Lag time needs to be considered. Lag is the difference between what the CGM currently reports and the actual glucose level due to delay in equilibration between the interstitial fluid and blood.48 This becomes salient in the following instances: first, when glucose is rapidly falling, yet the CGM reading is not yet in the hypoglycemic range while the patient may already be hypoglycemic, and second, when the patient has treated a low glucose with rapid-acting carbohydrate while the CGM may still register a low glucose value (Fig. 2d). To avoid over treatment of hypoglycemia, if the CGM continues to indicate hypoglycemia, it might be best to recheck a finger-stick glucose 15 min after treating the low to avoid rebound hyperglycemia.

8. Currently available subcutaneous rapid insulin analogs take 1–2 h to peak in the bloodstream and have a glucose-lowering effect that often lasts 4–5 h. Repetitive dosing of correction insulin, or multiple meal insulin doses, could lead to insulin “stacking” and an increased risk of hypoglycemia if a patient does not take into account the active insulin or the “insulin on board” (IOB). Nonadjunctive CGM use might lead to frequent use of correction doses, so patients need to be cautioned to allow at least 2–3 h to see the effect of a correction dose before redosing or to trust an insulin pump's IOB restrictions.49

9. There is an adjustment period as patients and families become accustomed to interpreting and acting on CGM data, as well as become adept at the technical and practical demands of operating CGM devices. It might be prudent to limit nonadjunctive use until patients/families become comfortable with this valuable management tool and can judge when a CGM result might be unreliable.

10. Finally, nonadjunctive CGM use would be inappropriate when a patient's symptoms do not match the CGM result, or when the value is unexpected or surprising. In that case, BGM verification would be appropriate. As a corollary, payers need to allow patients and their families a sufficient number of BGM supplies to accommodate those who judge it necessary to frequently verify CGM.

FIG. 2.

(a) Erratic and unreliable CGM tracing for the first 12 h of a new sensor placement, followed by improved function on day 2. (b) Examples of pressure-induced sensor attenuation (PISA) compression artifact, most commonly occurring at night. (c) Sensor tracings becoming less credible with non-physiologic swings, on days 13 and 14 of a sensor that was restarted to extend use. (d) Illustration of lag time-induced delayed CGM recovery after treatment of hypoglycemia. A hypoglycemia reading of 56 mg/dL was verified by BGM, and fruit juice consumed. Twelve minutes later, the blood glucose had corrected by BGM, but the CGM was still indicating hypoglycemia. Panels (a–c) were derived from a Dexcom G4P with 505 upgrade or G5 download to Dexcom Clarity. Panel (d) is a Dexcom G4P with Share receiver and OneTouch Verio Flex blood glucose meter.

FIG. 3.

Appearance of glucose number and a directional arrow (showing the direction of the glucose change) are both needed to use the CGM data for management decisions. Data displayed are from the Dexcom G4 or the Dexcom G4 with the 505 upgrade. The program is the Dexcom Share App running on an Apple iPhone.

While the above principles apply generally to use and particularly nonadjunctive CGM use, some issues are specific to different age groups. Below, we will discuss some of the factors in the two main age groups: pediatric patients and mature adults and seniors.

Nonadjunctive Considerations in Pediatrics

With the recent FDA approval for nonadjunctive CGM use for management decisions, the role of this technology in day care, preschools, and schools has become important to children, parents, and school nurses. In this context, providers must consider the decreased burden from fewer finger sticks in children against the risk of potential dosing errors from inappropriate use of CGM data from inexperienced day care or school personnel. While the FDA was clear on the benefit of trend arrows to augment CGM data and facilitate nonadjunctive CGM use,50 this approach requires education and experience. Experienced adult and teen patients along with parents may be able to integrate trend information into diabetes management decisions, but school personnel, which at times includes a “health aid,” educated adult, or a licensed medial provider who may not be accustomed to CGM, may be better suited to follow more prescriptive orders for insulin dosing and medical management.

Due to these concerns, our initial recommendations to families and schools concerning nonadjunctive CGM use outside the home are very conservative, favoring minimal decision-making by school health aids. We favor expanding these guidelines as additional clinical research and clinical experience on nonadjunctive use become available. These are the current guidelines we at the Barbara Davis Center are providing to schools regarding nonadjunctive CGM use:

General

1. The CGM should be calibrated twice a day generally when the BG is stable and not when after the child has eaten. This is usually done at home, but can be verified in the CGM calibration history.

2. APAP can falsely elevate CGM values, and the CGM readings should not be used for dosing within 4–8 h of APAP administration. Be cautious to check ingredient labels on any over-the-counter preparations, as many combination “cold and flu” medications contain APAP.

3. If a child is sent to the school nurse's office, another person must always accompany the child, especially if the child is hypoglycemic.

Meals

4. For meal-based correction boluses, the CGM value may be used provided the value is in the range of 80–250 mg/dL. If the CGM value is <80 mg/dL or >250 mg/dL, then a finger-stick BG value should be obtained and used for treatment decisions as per the school orders.

Hypoglycemia

5. If a child feels that his/her BG is low or if the CGM is reading <80 mg/dL, then check a finger-stick BG and provide carbohydrates based on the finger-stick BG reading and symptoms and recheck the finger-stick BG 15 min later. If still hypoglycemic, repeat the above.

6. If the CGM is indicating hypoglycemia (CGM <80 mg/dL), but the child is not symptomatic, confirm the glucose with a finger stick before treating. Treat according to the finger-stick value, as per the school orders. Recall that the very young child is unlikely to be symptomatic and will be unable to communicate hypoglycemic symptoms.

Hyperglycemia

7. If the CGM is reading >250 mg/dL, check a finger-stick BG and correct based on the finger-stick BG, as per the school orders.

8. If the finger-stick BG is >300 mg/dL, check blood or urine ketones and treat as per the school orders.

If the CGM sensor fails or falls out while the child is at school, back-up use of finger-stick BG data should be the rule. Also, the adolescent (and occasionally the older school age child) may perform diabetes self-management in the classroom without need to see a school nurse or health aide, depending on local regulations. CGM alerts should be set to allow for timely notifications for diabetes management but not so rigidly that frequent alerts could lead to alarm fatigue and a tendency for teens to ignore the CGM entirely. Finally, the teen should be encouraged to look at the mobile CGM display or the CGM receiver frequently to help with diabetes self-care and to ensure safety before driving.

Nonadjunctive Considerations in Adults and Older Adults

A major consideration of nonadjunctive CGM use in adults relates to the need to perform a verification finger stick properly, which can be challenging and even impossible at times, in a workplace setting. Patients may not have timely access to BGM supplies or facilities to wash hands. Furthermore, they may not be able to dispose of the waste products generated in a safe and sanitary manner.

The potential disruption of workplace duties, or potential biohazard exposure, might contribute to workplace discrimination, or at least the perception by adults with T1D of such discrimination. A survey on myglu.org from August 23, 2016,51 found that 26% of respondents thought they had been the victim of T1D-related workplace discrimination. In contrast, the correction of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia can be done quickly and more discretely with CGM than BGM. In addition, consistent CGM use may reduce the frequency of glycemic fluctuations and allow for quicker corrections, thereby reducing glycemic excursions and potentially improving workplace performance, allowing CGM users to reach their full potential in the workplace.

As noted previously, older adults are more susceptible to hypoglycemia and its consequences,20,23–25 and are more likely to suffer from comorbidities,20,22 Some older patients report more difficulty obtaining enough finger-stick blood for BGM determinations, perhaps due to the presence of neuropathy, arthritis, and circulatory disorders. Nonadjunctive CGM use can reduce the burden of frequent BGM determinations in this population, just as it can in very young children, and allow for timely intervention to limit severe glycemic excursions. Reduction in the number of BGM checks would also be expected to partially offset the costs of CGM.

Conclusions

CGM is a rapidly advancing technology that has shown benefit in improving glycemic outcomes and reducing patient burden. Expanded CGM indications and coverage will likely increase CGM uptake and help sustain durable CGM use, especially given the improved performance of modern CGM devices. Nonadjunctive treatment from CGM values is an important step toward improved glycemic control with reduced finger sticks. Given the recent approval of CGM for nonadjunctive use, despite previous off-label use, there are modest published empiric data to direct nonadjunctive CGM use. The most important principles for effective use are to verify readings that are unexpected, contradict symptoms, or do not appear credible while following appropriate recommendations for CGM calibration. Patients and caregivers also need to proceed cautiously with nonadjunctive use until they become experienced with CGM. As CGM technology improves and increased research becomes available, it is likely that CGM will replace painful finger sticks in all populations, reduce costs and burden, and improve glycemic control and overall health outcomes in patients with T1D and insulin-requiring patients with T2D.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge that the survey data were collected with assistance from the Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Exchange online community for research and engagement, Glu (myglu.org), which features a large cohort of people living with or caring for someone with T1D.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Forlenza is a consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care and conducts research sponsored by Dexcom, Medtronic, Insulet, Tandem, Bigfoot, Type-Zero, and Animas. Dr. Argento has served or is on advisory boards for Senseonics, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk, has done promotional and educational programs for Dexcom, Animas, Insulet, and the Johnson and Johnson Diabetes Institute, consulted for Eli Lilly, Insulet, and Intuity, and served on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. Dr. Laffel has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, MannKind, Dexcom, Insulet, and Menarini.

References

- 1.Cengiz E: Analysis of a remote system to closely monitor glycemia and insulin pump delivery—is this the beginning of a wireless transformation in diabetes management? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013;7:362–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodbard D: Continuous glucose monitoring: a review of successes, challenges, and opportunities. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18(Suppl 2):S23–S213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong JC, Foster NC, Maahs DM, et al. : Real-time continuous glucose monitoring among participants in the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2702–2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. : Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care 2015;38:971–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forlenza GP, Pyle LL, Maahs DM, Dunn TC: Ambulatory glucose profile analysis of the juvenile diabetes research foundation continuous glucose monitoring dataset-Applications to the pediatric diabetes population. Pediatr Diabetes 2016. November 23. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanenbaum ML, Hanes SJ, Miller KM, et al. : Diabetes device use in adults with type 1 diabetes: barriers to uptake and potential intervention targets. Diabetes Care 2017;40:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dexcom G5 Mobile Continuous Glucose Monitoring System - P120005/S041. 2016. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DeviceApprovalsandClearances/Recently-ApprovedDevices/ucm533969.htm (accessed December20, 2016)

- 8.Borus JS, Blood E, Volkening LK, et al. : Momentary assessment of social context and glucose monitoring adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck RW, Hirsch IB, Laffel L, et al. : The effect of continuous glucose monitoring in well-controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1378–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, et al. : Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1464–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.JDRF CGM Study Group: JDRF randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in the management of type 1 diabetes: research design and methods. Diabetes Technol Ther 2008;10:310–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck RW, Buckingham B, Miller K, et al. : Factors predictive of use and of benefit from continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1947–1953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.JDRF CGM Study Group: Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in a clinical care environment: evidence from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation continuous glucose monitoring (JDRF-CGM) trial. Diabetes Care 2010;33:17–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maahs DM, Buckingham BA, Castle JR, et al. : Outcome measures for artificial pancreas clinical trials: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1175–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damiano ER, McKeon K, El-Khatib FH, et al. : A comparative effectiveness analysis of three continuous glucose monitors: the Navigator, G4 Platinum, and Enlite. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014;8:699–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey TS, Chang A, Christiansen M: Clinical accuracy of a continuous glucose monitoring system with an advanced algorithm. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luijf YM, Avogaro A, Benesch C, et al. : Continuous glucose monitoring accuracy results vary between assessment at home and assessment at the clinical research center. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:1103–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laffel L: Improved accuracy of continuous glucose monitoring systems in pediatric patients with diabetes mellitus: results from two studies. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18(Suppl 2):S223–S233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh J, Roberts R, Weber D, et al. : Insulin pump and CGM usage in the United States and Germany: results of a real-world survey with 985 subjects. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:1103–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DCCT/EDIC Study Research Group: Mortality in type 1 diabetes in the DCCT/EDIC versus the general population. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1378–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhaliwal R, Weinstock RS: Management of type 1 diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Spectr 2014;27:9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thunander M, Petersson C, Jonzon K, et al. : Incidence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults and children in Kronoberg, Sweden. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;82:247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LM, Peters AL: Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2034–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, et al. : Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care 1997;20:135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cryer PE: Hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2010;39:641–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. : Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1384–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schütt M, Fach EM, Seufert J, et al. : Multiple complications and frequent severe hypoglycaemia in ‘elderly’ and ‘old’ patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2012;29:e176–e179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinstock RS, Xing D, Maahs DM, et al. : Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3411–3419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argento NB, Nakamura K: Personal real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients 65 years and older. Endocr Pract 2014;20:1297–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al. : Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin Injections: The DIAMOND Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Jan 24 2017;317(4):371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polonsky WH, Peters AL, Hessler D: The impact of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients 65 years and older. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2016;10:892–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dexcom CGM Resource Center. http://dexcom.com/reimbursement (accessed December11, 2016)

- 33.Medicare Website. www.medicare.gov (accessed December11, 2016)

- 34.CMS Ruling on CGM. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Rulings/Downloads/CMS1682R.pdf (accessed January16, 2017)

- 35.Pettus J, Price DA, Hill KJ, Edelman S: How people use direction and rate of change information provided by real-time continuous glucose monitoring (RT-CGM) to adjust insulin dosing. Diabetes Technol Ther 2014;16:19824401008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettus J, Price DA, Edelman SV: How patients with type 1 diabetes translate continuous glucose monitoring data into diabetes management decisions. Endocr Pract 2015;21:613–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Battelino T, Conget I, Olsen B, et al. : The use and efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes treated with insulin pump therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2012;55:3155–3162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riveline JP, Schaepelynck P, Chaillous L, et al. : Assessment of patient-led or physician-driven continuous glucose monitoring in patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes using basal-bolus insulin regimens: a 1-year multicenter study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:965–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinzimer SA, Steil GM, Swan KL, et al. : Fully automated closed-loop insulin delivery versus semiautomated hybrid control in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes using an artificial pancreas. Diabetes Care 2008;31:934–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pettus J, Edelman SV: Recommendations for using real-time continuous glucose monitoring (rtCGM) data for insulin adjustments in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2017;11:138–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edelman SV: Regulation catches up to reality: nonadjunctive use of continuous glucose monitoring data. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2017;160–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castle JR, Jacobs PG: Nonadjunctive use of continuous glucose monitoring for diabetes treatment decisions. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2016;10:1169–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dexcom G5 Mobile Continuous Glucose Monitoring System User Guide. Dexcom, Inc., 2016. Available online at http://www.dexcom.com/guides (accessed March21, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basu A, Veettil S, Dyer R, et al. : Direct evidence of acetaminophen interference with subcutaneous glucose sensing in humans: a pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18(Suppl 2):S243–S247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maahs DM, DeSalvo D, Pyle L, et al. : Effect of Acetaminophen on CGM glucose in an outpatient setting. Diabetes Care 2015;38:e158–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mensh BD, Wisniewski NA, Neil BM, Burnett DR: Susceptibility of interstitial continuous glucose monitor performance to sleeping position. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013;7:863–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Continuous Glucose Monitoring School. https://studies.jaeb.org/ndocs/extapps/CGMTeaching/Public/Default.aspx (accessed January22, 2017)

- 48.Bailey T, Zisser H, Chang A: New features and performance of a next-generation SEVEN-day continuous glucose monitoring system with short lag time. Diabetes Technol Ther 2009;11:749–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinemann L, Heise T, Wahl LC, et al. : Prandial glycaemia after a carbohydrate-rich meal in type I diabetic patients: using the rapid acting insulin analogue [Lys(B28), Pro(B29)] human insulin. Diabet Med 1996;13:625–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.FDA Advisory Panel Votes to Recommend Non-Adjunctive Use of Dexcom G5 Mobile CGM. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18:512–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glu - Type 1 Diabetes Exchange Community. https://myglu.org/polls/1930 (accessed January2, 2017)