Abstract

Phenotypically, Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida and P. damselae subsp. damselae are easily distinguished. However, their 16S rRNA gene sequences are identical, and attempts to discriminate these two subspecies by molecular tools are hampered by their high level of DNA-DNA similarity. The 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacers (ITS) were sequenced in two strains of Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida and two strains of P. damselae subsp. damselae to determine the level of molecular diversity in this DNA region. A total of 17 different ITS variants, ranging from 803 to 296 bp were found, some of which were subspecies or strain specific. The largest ITS contained four tRNA genes (tDNAs) coding for tRNAGlu(UUC), tRNALys(UUU), tRNAVal(UAC), and tRNAAla(GGC). Five amplicons contained tRNAGlu(UUC) combined with two additional tRNA genes, including tRNALys(UUU), tRNAVal(UAC), or tRNAAla(UGC). Five amplicons contained tRNAIle(GAU) and tRNAAla(UGC). Two amplicons contained tRNAGlu(UUC) and tRNAAla(UGC). Two different isoacceptor tRNAAla genes (GGC and UGC anticodons) were found. The five smallest amplicons contained no tRNA genes. The tRNA-gene combinations tRNAGlu(UUC)-tRNAVal(UAC)-tRNAAla(UGC) and tRNAGlu(UUC)-tRNAAla(UGC) have not been previously reported in bacterial ITS regions. The number of copies of the ribosomal operon (rrn) in the P. damselae chromosome ranged from at least 9 to 12. For ITS variants coexisting in two strains of different subspecies or in strains of the same subspecies, nucleotide substitution percentages ranged from 0 to 2%. The main source of variation between ITS variants was due to different combinations of DNA sequence blocks, constituting a mosaic-like structure.

In bacteria, 16S and 23S rRNA genes are separated by a spacer region, which is transcribed together with the ribosomal genes and thus is named an internal transcribed spacer(s) (ITS). These genomic regions show a high degree of variability between species, both in their base length and in their sequence (11). The fact that most bacterial species harbor multiple copies (alleles) of the ribosomal operon in their genome increases the possibility that a substantial amount of sequence variation exists in these spacer regions, even among strains of the same species. This diversity represents a powerful tool for the design of specific oligonucleotides for PCR-based detection protocols (17, 19, 33, 35) or to discriminate species on the basis of the band patterns obtained by PCR amplification of the spacer regions (7, 15).

The length of the ITS regions located between 16S and 23S rRNA genes show a wide variation both among species (from 60 pb in Thermoproteus tenax to 1,529 pb in Bartonella elizabethae) and among different copies of the ribosomal operon within a chromosome (303 to 551 bp in Staphylococcus aureus and 478 to 723 in Haemophilus influenzae). These length variations in ITS region are due, mainly, to the type and number of tRNA genes interspersed. Most gram-negative bacteria contain tRNAAla and tRNAIle genes, whereas some contain only tRNAGlu. Nevertheless, new combinations of tRNA genes have been described recently in Vibrio species (5, 19, 22).

Pasteurellosis or pseudotuberculosis is one of the most important fish diseases in marine aquaculture, causing substantial economic losses in marine fish cultures worldwide (23). The causative agent, formerly Pasteurella piscicida, has been reclassified as Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida (9), thus sharing species level status with Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae (formerly Vibrio damsela). P. damselae subsp. damselae is a halophilic bacterium that has been reported to cause wound infections and fatal disease in a variety of marine animals and also in humans (4, 6, 24). These two subspecies differ in biochemical and physiological traits such as motility, gas production from glucose, nitrate reduction, urease, lipase, amylase and hemolysin production, and range of temperature and salinity for growth, as well as host specificity (8, 23). Actually, an extensive study of morphological and biochemical traits suggested that P. damselae subsp. piscicida and subsp. damselae should not be included within the same species (34). However, the two subspecies of P. damselae show a high degree of overall DNA base sequence similarity, as revealed by chromosomal DNA-DNA pairing (9). Similarly, the two subspecies are reported to possess identical 16S rRNA gene sequences (26).

In the present study the nucleotide sequences of ITS of strains belonging to the two subspecies of P. damselae were analyzed. Comparison of these ITS has allowed the determination of variability in the number and size of sequence blocks and variation in the number of rrn operons in P. damselae strains. New tRNA gene combinations not previously known in bacterial ITS regions are also reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

P. damselae subsp. damselae strains (RG91, from Scophthalmus maximus, Spain; ATCC 33539, from Chromis punctipinnis, United States) and subsp. piscicida strains (DI21, from Sparus aurata, Spain; ATCC 29690, from Seriola quinqueradiata, Japan) were grown aerobically on Trypticase soy agar plates at 25°C. Escherichia coli DH5-α was grown at 37°C in Trypticase soy agar. Plasmids pCRTOPO (Invitrogen) and pUC118 (36) were used for cloning.

DNA extraction, primer design, and PCR amplification of ITS.

Genomic DNA was extracted as described elsewhere (26). Plasmid DNA was purified according to standard procedures (32), as well as with a plasmid miniprep kit (Qiagen). DNA was extracted from agarose gels by using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

All of the primers used in the present study are described in Table 1. A forward primer AntiR and a reverse primer 23S23-38 were designed on the basis of the 16S rRNA gene (EMBL accession number Y18496) and the 23S rRNA gene of P. damselae subsp. piscicida (EMBL accession number Y17901), respectively. This pair of oligonucleotides was selected to amplify the complete ITS regions of the four strains studied. PCRs were performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Biometra) by using Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Additional primers (Table 1) were designed to carry out internal amplifications within the ITS regions described here.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer (orientation)a | Sequence (5′→3′) | Position (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| AntiR (f) | ACACACGTGCTACAATG | 16S rRNA (1223-1239) |

| 23S-23-38 (r) | TGCCAAGGCATCCACC | 23S rRNA (23-38) |

| 16S-3′ (f) | TAGATAGCTTAACCTTC | 16S (1424-1440) |

| Spa20-15-rev (f) | GAAGTGGTTCGAAAGAAACAC | Region 52 |

| Spa120-end (r) | ACACAAGACACTTGAATGTG | Region 120 |

| 23S-5′-IIII (f) | CAGTAAGTACTATCCGGGAG | 23S rRNA (912-931) |

| 23S-5′-III (r) | CTGTAGTAAAGGTTCACGG | 23S rRNA (2072-2054) |

| PA (f) | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 16S (9-28) |

| PH (r) | AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA | 16S (1521-1540) |

| Glu-prev (f) | GCCACTTAATGTTGCCCAACAAC | Glu-tRNA 5′ end |

| 5′-IN (f) | CAGTTGGTAGAGCAGTTG | Internal to Lys-tRNA |

| 202-15 (r) | GTGTTTCTTTCGAACCACTT | Region 52 |

| 123 (r) | TCATTGAATCTGCGAATCCGTGC | Region 123 in ITS-803 |

f, forward primer; r, reverse primer.

With primers AntiR and 23S23-38, amplification was carried out with denaturation at 95°C for 4 min, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. A final extension step of 5 min at 72°C was also carried out. Internal amplifications with additional primers were similarly carried out, adjusting the annealing temperatures and elongation times as necessary (data not shown).

Cloning of ITS and DNA sequencing.

PCR products were cloned by using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant colonies were picked and grown in 3 ml of Luria-Bertani broth containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml), for 12 to 18 h at 37°C. Purified plasmids were cut with EcoRI, and screening of the different insert sizes was carried out with 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Sequencing reactions were performed by using the Taq DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (ABI) and an ABI 373 automated DNA sequencer. A sequencing primer 16S-3′ was selected for the 5′-end reaction. For the 3′-end reaction, 23S23-38 primer was used. Both DNA strands were sequenced to completion.

Direct cloning of ITS regions from the chromosome.

Chromosomal DNA of P. damselae subsp. piscicida DI21 was cut with EcoRI and HindIII, and DNA fragments in the range of 1 to 2 kb were extracted from agarose gels, ligated to pUC118 plasmid that had been similarly digested, and transformed in E. coli DH5-α. Pools of colonies were screened by PCR with the specific primers spa20-15-rev and spa120-end. Nucleotide sequences of positive clones were compared to those previously obtained after PCR amplification.

Data analysis.

ITS DNA sequences were aligned by using the programs PILEUP version 8 from Genetics Computing Group (GCG; University of Wisconsin) and CLUSTAL W. Alignment between groups of sequences was adjusted manually by using GENEDOC. To find out conserved regions within the different ITS amplicons and among the different P. damselae strains, programs PRETTYBOX and GAP (GCG) were also used. The programs STEMLOOP, REPEAT, and FINDPATTERNS (GCG) were used to search for repeated sequences. Secondary structure prediction for putative tRNA genes was done by using tRNA-Scan software (21).

Southern hybridization analysis.

Restriction map of P. damselae ribosomal genes and spacer sequences was determined with the MAP program (GCG). A 1,170-bp internal fragment of P. damselae subsp. piscicida DI21 23S rRNA gene was PCR amplified with the specific primers 23S-5′-IIII and 23S-3′-III and used as a probe. In addition, 16S gene was amplified with the primers PA and PH, the PCR product was cut with BglII, and a fragment corresponding to the first ca. 700 bp of 16S rRNA gene was gel purified and used as a probe.

The chromosomal DNA of the four P. damselae strains used in the present study was digested with BglII and double digested with BglII-PstI and BglII-HindIII. Digestion products were separated on 0.6% agarose gels to enhance the separation of high-molecular-mass bands. Southern blotting was done by using an ECL DNA labeling and detection kit (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

EMBL accession numbers.

The EMBL accession numbers for the ITS sequences are AJ274375, AJ274376, AJ274377, AJ274378, AJ535842, AJ535843, AJ535844, AJ535845, AJ535846, AJ535847, AJ535848, AJ535849, AJ535850, AJ535851, AJ535852, AJ535853, and AJ535854.

RESULTS

PCR of P. damselae ITS.

Strains of P. damselae subsp. piscicida ATCC 29690 and DI21 (26) and P. damselae subsp. damselae ATCC 33539 and RG91 (26) were subjected to 16S-23S ITS region amplification with the primers AntiR and 23S-23-38. A similar pattern for the four P. damselae strains was obtained (data not shown), consisting on a collection of DNA bands with sizes ranging approximately from 650 bp to 1,100 bp. Since primer AntiR starts amplification from position 1223 in the P. damselae 16S rRNA gene, the actual size of the ITS regions is ca. 300 bp shorter than their respective PCR amplicons.

Sequence analysis of ITS.

After complete sequence analysis of 119 clones (ATCC 29690, 40 clones; ATCC 33539, 40 clones; DI21, 20 clones; RG91, 19 clones), 17 different ITS amplicon sizes were found, taking together the results for the four strains analyzed. In strain DI21, seven distinct ITS types of 296, 331, 350, 504, 539, 592, 689, and 803 bp were found. For strain ATCC 29690, nine sizes of 296, 331, 350, 504, 558, 588, 592, 646, and 803 bp were evident. In strain RG91, 10 sizes of 296, 315, 350, 504, 509, 523, 539, 544, 558, and 611 bp were found, whereas in strain ATCC 33539, seven ITS variants of 296, 315, 350, 504, 509, 523, and 611 bp were sequenced. ITS sequences with similar length were pooled in different groups and analyzed. All of the ITS sequences shared the first 45 and the last 21 bp. The interspersed sequences between these conserved ends were composed of a collection of sequence blocks that were not present in all of the ITS. Some ITS sequences showed regions with similarity to described tRNA genes. Presence of tRNA genes was also confirmed by secondary structure predictions. When the same ITS amplicon size was sequenced in two strains of the same subspecies or when the same ITS size was found in the two subspecies of P. damselae, the similarity percentage was >98%. P. damselae ITS regions were classified into four groups: (i) ITS without tRNA genes; (ii) ITS with tRNAIle(GAU) and tRNAAla(UGC) genes; (iii) ITS with tRNAGlu(UUC), tRNAAla(UGC), and some with a tRNAVal(UAC) gene; and (iv) ITS with tRNAGlu(UUC), tRNALys(UUU) tRNAVal(UAC), and tRNAAla(GGC).

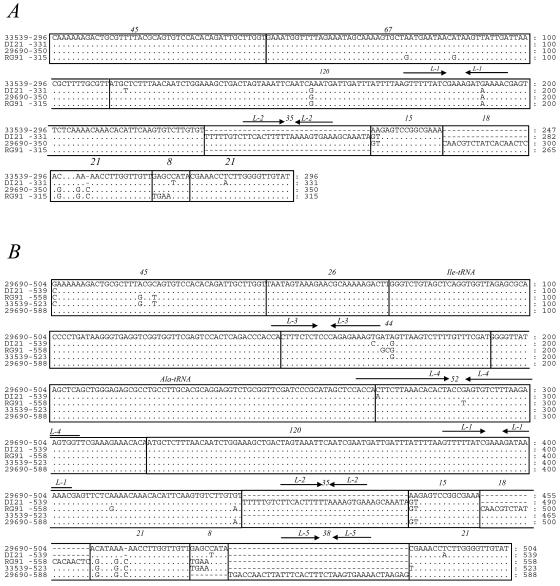

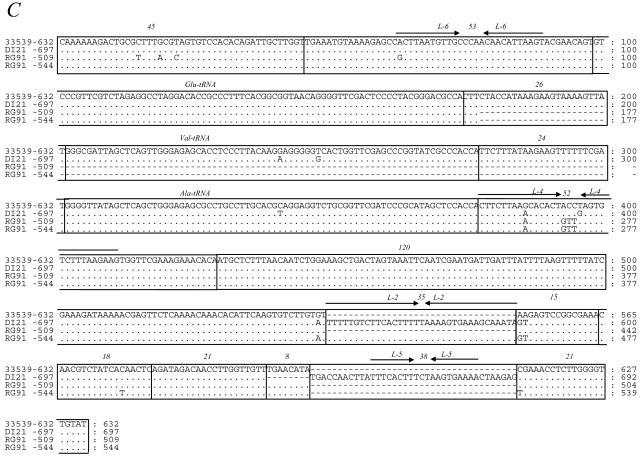

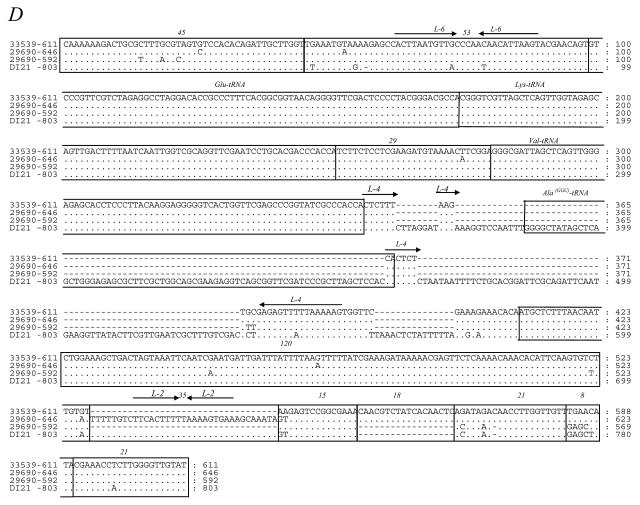

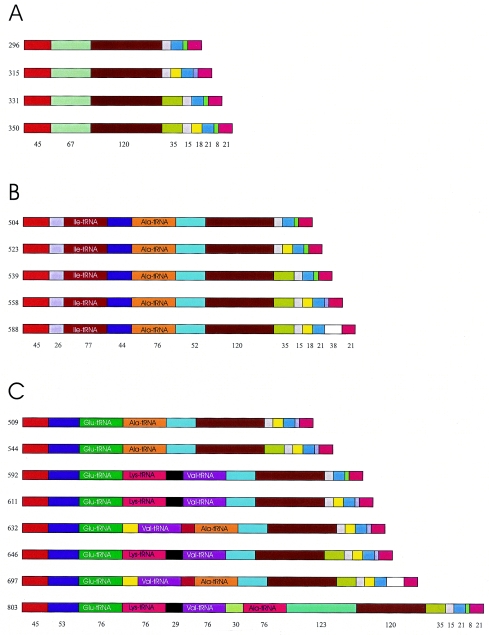

One clone of each ITS size was chosen to be shown in the alignments, regardless of the strain from which it was amplified. The four ITS lacking tRNA genes (group 1) all shared the same DNA sequence except for the 3′-end region, which showed a mosaic-like structure originated by insertions/deletions of short DNA sequence blocks of sizes ranging from 38 to 8 bp in different combinations (Fig. 1A and 2A). Each of these DNA blocks, when present, always occupied the same relative position respective to the other existing blocks.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of representative ITS sequences of P. damselae subspecies and strains corresponding to group 1 (A), group 2 (B), group 3 (C), and group 4 (D). Nucleotide positions that are conserved are indicated by dots. Gaps that have been included to obtain optimal sequence alignment are indicated by dashes. The different sequence blocks are enclosed in boxes and labeled with numbers, indicating their sequence length. Inverted repeats with palindromic structure are denoted by pairs of inverted arrows and designated as L-1 to L-6. The type of ITS spacer and the strain are indicated on the left. Numbers on the right indicate spacer lengths at different intervals.

FIG. 2.

Mosaic-like structure of ITS from sequence alignments in Fig. 1. Colors indicate discrete sequence blocks that are common between different ITS. Mosaic structures of ITS from group 1 (A), group 2 (B), and groups 3 and 4 (C) are shown. Numbers on the left indicate the sequence lengths of the ITS. Numbers at the bottom indicate the lengths of the discrete sequence blocks.

Group 2 includes five different versions of ITS with sizes of 504, 523, 539, 558, and 588 bp and containing two tRNA genes (tRNAIle and tRNAAla) (Fig. 1B and 2B). All of the amplicons showed the same structure except in their 3′ ends. Combination of short sequence blocks occurred in the same order as in group 1, but a new short DNA block of 38 bp was evidenced in the 588-bp amplicon (Fig. 2B). The internal region of group 2 ITS sequences did not have homology to the internal sequences of group 1, except for a 120-bp DNA block (region 120) that is present in all of the ITS sequences described in the present study.

Group 3 comprises two ITS sequences containing tRNAGlu and tRNAAla genes, as well as two ITS that, in addition, contained a tRNAVal gene. Their sizes are 509, 544, 632, and 697 bp, respectively, and their sequence alignment and mosaic structures are represented in Fig. 1C and 2C, respectively. ITS amplicons of 509 and 544 bp, which are found in P. damselae subsp. damselae, contain the tRNA genes for glutamate and alanine (Glu-Ala). In addition, 632- and 697-bp ITS contain the tRNA gene organization Glu-Val-Ala. These two tRNA gene combinations are described here for the first time in bacterial ITS.

Group four comprises ITS amplicons of 592, 611, and 646 bp containing tRNAGlu, tRNALys, and tRNAVal as well as an ITS amplicon of 803 bp, which, in addition to the aforementioned three tRNA genes, also harbored a new tRNAAla(GGC) gene that is different from the tRNAAla(UGC) gene encountered in other ITS-1 of groups 2 and 3. Comparative alignment and mosaic structure are represented in Fig. 1D and 2C, respectively. The present study represents the first report of the occurrence of tRNAGlu-tRNALys-tRNAVal-tRNAAla genes in ITS of a non-Vibrio species. In addition, it represents the first report on the existence of two different isoacceptor tRNAAla genes, as well as the first report of an ITS region with genes tRNAGlu-tRNAVal-tRNAAla (ITS of 632 and 697 bp) in a non-Vibrio species.

Some sequence blocks of ITS described here constitute short inverted repeats. These palindromic regions, which form a hairpin-like secondary structure, may have a function in the formation of stem-loop structures during processing of RNA transcript to produce mature tRNAs (labeled L-1 to L-6 in Fig. 1). The so-called region 120 is a 120-bp constant DNA block that is found in all of the ITS sequences described in the present study (Fig. 1 and 2), being highly conserved in its primary structure. The first bases of region120 (TGCTCTTT) show 100% similarity to the so-called boxA sequence of E. coli and other bacterial species. This boxA element plays a role in antitermination of rRNA transcription.

Results of internal amplifications.

As the number of sequenced PCR clones increased, it became less frequent to find new ITS amplicons for each strain. Thus, internal amplifications with primers whose amplification products can be predicted and interpreted were used to carry out a screening of ITS variants in each strain. PCR products were extracted from agarose gel and directly sequenced. All of the data were in conformity with those obtained previously by sequencing of ITS clones. To summarize all of the results obtained by both the sequencing of clones and the sequencing of products of internal amplifications, all of the different ITS regions sequenced in the present study and their deduced presence in each of the four strains analyzed are presented in Table 2. No sequence blocks have been found to be strain specific. The four strains examined here shared the same pool of sequence blocks, albeit the order in which they are combined shows inter- and intrasubspecies variation.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the different ITS amplicons of P. damselae described in this studya

| Size (bp) | Location | tRNA gene status |

|---|---|---|

| 296 | Both subspecies | No tRNAs |

| 315 | Subsp. damselae | No tRNAs |

| 331 | Subsp. piscicida | No tRNAs |

| 350 | Both subspecies | No tRNAs |

| 504 | Both subspecies | Ile-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 509 | Subsp. damselae | Glu-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 523 | Subsp. damselae | Ile-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 539 | DI21, RG91 | Ile-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 544 | Subsp. damselae | Glu-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 558 | ATCC 29690, RG91 | Ile-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 588 | ATCC 29690 | Ile-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 592 | Subsp. piscicida | Glu-tRNA, Lys-tRNA, Val-tRNA |

| 611 | Subsp. damselae | Glu-tRNA, Lys-tRNA, Val-tRNA |

| 632 | ATCC 33539 | Glu-tRNA, Val-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 646 | Subsp. damselae, ATCC 29690 | Glu-tRNA, Lys-tRNA, Val-tRNA |

| 697 | Subsp. piscicida | Glu-tRNA, Val-tRNA, Ala-tRNA |

| 803 | Both subspecies | Glu-tRNA, Lys-tRNA, Val-tRNA, Ala*-tRNA (*isoacceptor) |

The presence of each size type in the four analyzed strains is indicated, as well as the type of tRNA genes, when present. Strains DI21 and ATCC 29690 are subsp. piscicida; strains RG91 and ATCC 33539 are subsp. damselae.

Direct cloning and sequencing of ITS from the chromosome.

Representatives of ITS regions directly cloned from the chromosome of P. damselae subsp. piscicida DI21 were sequenced and compared to those previously obtained by PCR amplification. Ten analyzed clones were 100% identical to sequences of ITS of 504 and 588 (group 2), 697 (group 3), and 592 bp (group 4) obtained previously by PCR amplification and sequencing. This provided strong evidence that the variability of spacer regions and the combination of sequence blocks and tRNA genes exists in vivo and is not due to PCR artifacts.

Determination of rrn operon copy number by DNA hybridization.

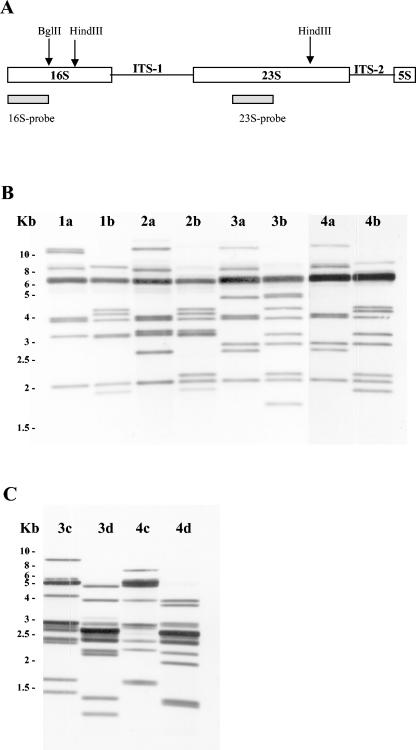

A restriction map of the consensus P. damselae rrn operon showing the locations of DNA probes is shown in Fig. 3A. Hybridization with 23S gene probe on BglII- and BglII-PstI-digested DNA yielded a pattern of high-molecular-mass bands (data not shown), which made it difficult to ascertain the copy number. The same DNA blot was hybridized with a 16S gene probe (Fig. 3B). All of the strains shared a band with a strong hybridization signal that might comprise more than one distinct rrn-containing DNA fragment.

FIG. 3.

(A) Restriction map of P. damselae rrn operon. (B) Results of hybridization with 16S probe on chromosomal DNA digested with BglII and double-digested with BglII-PstI. (C) Results of hybridization with 16S probe on chromosomal DNA digested with HindIII and double-digested with HindIII-BglII. Lane designations: 1, DI21; 2, ATCC 29690; 3, RG91; 4, ATCC 33539; a, DNA digested with BglII; b, DNA double digested with BglII and PstI; c, DNA digested with HindIII, d, DNA double digested with HindIII-BglII.

DNA of strains RG91 and ATCC 33539 was digested with HindIII and double digested with HindIII and BglII and then hybridized with 16S gene probe (Fig. 3C). Bands with double intensity were evidenced, which could comprise more than one rrn-containing DNA band. According to these results, strain DI21 has at least 9 rrn operons and ATCC 29690 has at least 10, whereas RG91 and ATCC 33539 have at least 12. Although the actual rrn copy numbers could not be unambiguously determined, the results suggest that rrn operon numbers vary between strains and subspecies in P. damselae. Altogether, hybridization results demonstrated that the number of ITS versions found for each strain is in accordance with the minimal number of rrn operons deduced after ITS sequencing.

DISCUSSION

Nucleotide sequences of ITS located between 16S and 23S rRNA genes have been successfully used to differentiate closely related bacterial taxa (11, 19, 37). In our study, we attempted to use ITS sequences in order to obtain information about the variation occurring among P. damselae subspecies and strains. As we demonstrated in previous studies, 16S rRNA gene consensus sequence showed no variation between 19 and 10 subsp. piscicida and subsp. damselae strains analyzed, respectively.

In the present study we selected two strains from each subspecies. Sequencing analysis revealed that genetic diversity exists not only between subspecies but also between strains of the same subspecies. DNA size of P. damselae ITS sequences are similar to those described for ITS regions of other species of family Vibrionaceae. For example, ITS with sizes ranging from 277 to 705 bp have been reported in Vibrio parahaemolyticus (22).

Sequence alignment of P. damselae ITS revealed a mosaic-like structure. The nucleotide sequence at both ends is conserved between amplicons, which may be due to their involvement in the rRNA processing mechanism. Internal sequence stretches are also conserved, as is the case of box A in region 120, which has a putative role in rRNA-transcription antitermination. However, the rest of the spacer sequence is constituted by a collection of sequence blocks that vary between rrn operons. Modular organization of DNA blocks in a mosaic-like fashion is a characteristic of bacterial intergenic spacer regions (12, 13) and has been reported in Salmonella enterica (29), Haemophilus influenzae (31), Staphylococcus aureus (10) Vibrio mimicus (5), Vibrio cholerae (5, 18), and V. parahaemolyticus (22). Combination of different sequence blocks in a mosaic-like fashion encountered at the 3′ end of all of the P. damselae spacers is more diverse than in related species. For example, the six different types of ITS that have been reported in V. parahaemolyticus, all share a 180-bp sequence at their 3′ ends (22), whereas in P. damselae, only the last 21 bp are conserved in all of the ITS.

The number of tRNA genes coexisting in a bacterial ITS region varies from zero to four. It was in V. cholerae and V. mimicus where tRNALys and tRNAVal were first reported to occur in ITS regions of prokaryotes (5). Later, these same genes were reported in ITS regions of V. parahaemolyticus, as well as the occurrence of four tRNA genes (tRNAGlu, tRNALys, tRNAAla, and tRNAVal) in an ITS amplicon of that species, which represented the first report in prokaryotes (22). A database search of V. cholerae complete genome sequence (14) demonstrated that one ribosomal operon of this species also contains the combination tRNAGlu-tRNALys-tRNAVal-tRNAAla, which had not been previously found in studies reporting ITS analysis of V. cholerae. Similarly, an EMBL database search of the Vibrio vulnificus complete genome sequence showed the existence of an ITS region with these four tRNA genes. New tRNA-gene combinations occurring in ITS regions of bacteria have been recently described, as is the case of Glu-Ala-Val in V. fluvialis and V. nigripulchritudo and of Ile-Ala-Val in V. proteolyticus (19). Analysis of P. damselae ITS regions also showed two new tRNA-gene combinations, i.e., Glu-Val-Ala and Glu-Ala which, to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported in bacterial ITS regions.

It is feasible that some of the genetic diversity found in P. damselae ITS amplicons was generated from homologous recombination between rRNA gene loci. The largest amplicon (803 bp) may have undergone homologous recombination with other tRNA gene clusters within the genome, via its homology with Glu-, Lys- or Val-tRNA genes, taking a copy of the tRNAAla(GGC) isoaceptor together with flanking DNA, thus explaining why DNA sequences flanking tRNAAla(GGC) gene are uniquely found in the 803-bp amplicon. Events of homologous recombination between tRNA genes have been proposed to explain the rearrangement of rrn operons in V. cholerae (18), and Salmonella enterica (20).

Similarly, recombination between rrn operons not only may have contributed to the homogenization within the shared sequence blocks (concerted evolution) but also may have facilitated the emergence of some ITS mosaic combinations. For example, all of the ITS sequences containing the Ala-tRNA share a sequence stretch downstream of that tRNA gene (region 52), whereas the upstream sequence of Ala-tRNA may constitute one of three different combinations of tRNAs, i.e., Ile-Ala, Glu-Ala, or Glu-Val-Ala. In this sense, the first half of the 697-bp spacer can be seen as a combination of the first half of the 588-bp spacer, whereas its second half is identical to other spacers of groups 3 and 4.

When one ITS amplicon was found in all of the subspecies and strains analyzed, the nucleotide sequences showed similarity percentages higher than 98%. This means that the main intraspecies evolutionary divergence is due to the rearrangement of sequence blocks shared by all of the strains rather than to the accumulation of mutations, which would generate strain-specific sequence blocks. The high percentage of sequence similarity between the ITS regions of the two subspecies clearly supports the taxonomic placement of P. damselae subsp. damselae and P. damselae subsp. piscicida under the same species name, although reported phenotypic studies suggested that they should not share species epithet (34).

All of the ITS alleles described in P. damselae contained at least one of six different inverted repeats. Existence of short inverted repeat sequences, which can form putative stem-loop structures within ITS regions has been reported in bacterial taxa (25). It is believed that some of these palindromic structures may be related to the genetic events responsible for the insertion/deletion of DNA sequence blocks.

The number of copies of the ribosomal operon may vary from one to as many as 15 (1, 16). Published ribosomal operon copy numbers in Vibrionaceae species studied thus far vary from at least nine in V. parahaemolyticus (22) to eight in V. cholerae (14). However, in the recently created rrndb database for rRNA operon copy number (16) (http://rrndb.cme.msu.edu), it is reported that as many as 13 rRNA operons have been encountered in Vibrio natriegens. In our study, the number of ribosomal operons in P. damselae strains varied between at least 9 and 12, but a higher number of copies may exist at least in subsp. damselae strains. The rrn copy number is not necessarily conserved among all of the species of a genus, as has been proved for Streptococcus (3), Streptomyces (2, 30), and Bacillus (27) spp. Differences in rrn copy number also exist between strains of the same species. For example, Streptococcus thermophilus contains six rrn operons, but some strains have been found with five rrn copies due to a deletion (28). Similarly, rrn copy numbers of 7, 8, and 9 have been reported in different V. cholerae strains (1).

In the present study we have shown that the ITS regions of P. damselae consist of constant and variable regions, where combinations of variable regions lead to the existence of 17 different ITS types. However, no specific sequences exist in either of the subspecies. This strongly suggests that recombination and concerted evolution are responsible for the exchange of nucleotide blocks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roger Hutson (School of Food Biosciences, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom) and Volker Gürtler (Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre, Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia) for kind suggestions and useful comments.

This study was supported by grants MAR1999-0478, ACU01-012, and AGL-2000-0492 from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (Spain).

REFERENCES

- 1.Acinas, S. G., L. A. Marcelino, V. Klepac-Ceraj, and M. F. Polz. 2004. Divergence and redundancy of 16S rRNA sequences in genomes with multiple rrn operons. J. Bacteriol. 186:2629-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baylis, H. A., and M. J. Bibb. 1988. Organization of the rRNA genes in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Gen. Genet. 211:191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, R. W., and J. A. Leigh. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA gene copy number in Streptococcus uberis, S. agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae, and S. parauberis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 12:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck, J. D., N. A. Overstrom, G. W. Patton, H. F. Anderson, and J. F. Gorzelany. 1991. Bacteria associated with stranded cetaceans from the northeast USA and southwest Florida Gulf coasts. Dis. Aquat. Org. 10:147-152. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun, J., A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 1999. Analysis of 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2202-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarridge, J. E., and S. Zighelboim-Daum. 1985. Isolation and characterization of two hemolytic phenotypes of Vibrio damsela associated with a fatal wound infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21:302-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daffonchio, D., S. Borin, A. Consolandi, D. Mora, P. L. Manachini, and C. Sorlini. 1998. 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacers as molecular markers for the species of the 16S rRNA group I of the genus Bacillus. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 163:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fouz, B, J. L. Larsen, B. Nielsen, J. L. Barja, and A. E. Toranzo. 1992. Characterization of Vibrio damsela strains isolated from turbot Scophthalmus maximus in Spain. Dis. Aquat. Org. 12:155-166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauthier, G., B. Lafay, R. Ruimy, V. Breittmayer, J. L. Nicolas, M. Gauthier, and R. Christen. 1995. Small-subunit rRNA sequences and whole DNA relatedness concur for the reassignment of Pasteurella piscicida (Snieszko et al.) Janssen and Surgalla to the genus Photobacterium as Photobacterium damsela subsp. piscicida comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gürtler, V., and H. D. Barrie. 1995. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains by PCR-amplification of variable-length 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions: characterization of spacer sequences. Microbiology 141:1255-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gürtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 142:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gürtler, V. 1999. The role of recombination and mutation in 16S-23S rDNA spacer rearrangements. Gene 238:241-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gürtler, V., and B. C. Mayall. 1999. rDNA spacer rearrangements and concerted evolution. Microbiology 145:2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen, M. A., J. A. Webster, and N. Straus. 1993. Rapid identification of bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:945-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klappenbach, J. A., P. R. Saxman, J. R. Cole, and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. rrndb: the rRNA operon copy number database. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:181-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong, R. Y. C., A. Pelling, C. L. So, and R. S. S. Wu. 1999. Identification of oligonucleotide primers targeted at the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacers for genus- and species-specific detection of aeromonads. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 38:802-808. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan, R., and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Recombination between rRNA operons created most of the ribotype variation observed in the seventh pandemic clone of Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 144:1213-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, S. K. Y., H. Z. Wang, S. H. W. Law, R. S. S. Wu, and R. Y. C. Kong. 2002. Analysis of the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacers (IGSs) of marine vibrios for species-specific signature DNA sequences. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 44:412-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, S. L., and K. E. Sanderson. 1998. Homologous recombination between rrn operons rearranges the chromosome in host-specialized species of Salmonella. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe, T. M., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda, T., N. Takada, M. Furushita, and T. Shiba. 2000. Structural variation in the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacers of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magariños, B., A. E. Toranzo, and J. L. Romalde. 1996. Phenotypic and pathobiological characteristics of Pasteurella piscicida. Annu. Rev. Fish. Dis. 6:41-64. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris, J.G, Jr., R. Wilson, D. G. Hollis, R. E. Weaver, H. G. Miller, C. O. Tacket, F. W. Hickman, and P. A. Blake. 1982. Illness caused by Vibrio damsela and Vibrio hollisae. Lancet i:1294-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naïmi, A., G. Beck, and C. Branlant. 1997. Primary and secondary structures of rRNA spacer regions in enterococci. Microbiology 143:823-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osorio, C. R., M. D. Collins, A. E. Toranzo, J. L. Barja, and J. L. Romalde. 1999. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of Photobacterium damselae and nested PCR method for the rapid detection of the causative agent of fish pasteurellosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2942-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patra, G., A. Fouet, J. Vaissaire, J.-L. Guesdon, and M. Mock. 2002. Variation in rRNA operon number as revealed by ribotyping of Bacillus anthracis strains. Res. Microbiol. 153:139-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pébay, M., Y. Roussel, J. Simonet, and B. Decaris. 1992. High-frequency deletion involving closely spaced rRNA gene sets in Streptococcus thermophilus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 98:51-56. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez-Luz, S., F. Rodríguez-Valera, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Variation of the ribosomal operon 16S-23S gene spacer region in representatives of Salmonella enterica subspecies. J. Bacteriol. 180:2144-2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pernodet, J.-L., J.-L. Boccard, M.-T. Alegre, J. Gagnat, and M. Guerineau. 1989. Organization and nucleotide sequence analysis of a rRNA gene cluster from Streptomyces ambofaciens. Gene 79:33-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Privitera, A., G. Rappazzo, P. Sangari, V. Gianninò, L. Licciardello, and S. Stefani. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of a 16S/23S ribosomal spacer from Haemophilus parainfluenzae reveals an invariant, mosaic-like organization of sequence blocks. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164:289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Smart, C. D., B. Schneider, C. L. Blomquist, L. J. Guerra, N. A. Harrison, U. Ahrens, K.-H. Lorenz, E. Seemuller, and B. C. Kirkpatrick. 1996. Phytoplasma-specific PCR primers based on sequences of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer region. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2988-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thyssen, A., Grisez, L., van Houdt, R., and Ollevier, F. 1998. Phenotypic characterization of the marine pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1145-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilsala-Timisjärvi, A., and T. Alatossava. 1997. Development of oligonucleotide primers from the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic sequences for identifying different dairy and probiotic lactic acid bacteria by PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 35:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villard, L., A. Kodjo, E. Borges, F. Maurin, and Y. Richard. 2000. Ribotyping and rapid identification of Staphylococcus xylosus by 16S-23S spacer amplification. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]