Abstract

Centromeres are essential chromosomal structures that mediate the accurate distribution of genetic material during meiotic and mitotic cell divisions. In most organisms, centromeres are epigenetically specified and propagated by nucleosomes containing the centromere-specific H3 variant, CENP-A. Although centromeres perform a critical and conserved function, CENP-A and the underlying centromeric DNA are rapidly evolving. This paradox has been explained by the centromere drive hypothesis, which proposes that CENP-A is undergoing an evolutionary tug-of-war with selfish centromeric DNA. Here, we review our current understanding of CENP-A evolution in relation to centromere drive and discuss classical and recent advances, including new evidence implicating CENP-A chaperones in this conflict.

Keywords: Centromeres, meiosis, chromosome segregation, centromere drive, CENP-A, centromere evolution, Drosophila

Epigenetic specification of centromeres

Centromeres dictate the position where kinetochores, nano-machines that mediate the pole-ward transport of chromosomes during cell division, assemble [1]. While centromere function is highly conserved, significant variation exists across organisms with respect to centromeric DNA sequences and centromeric proteins employed. In this review, we provide a brief summary of known attributes of centromeres (recently reviewed more extensively in [2]) and focus on the evolutionary conundrums surrounding these fascinating genomic regions in an attempt to reconcile models accounting for the rapid evolution of centromeres and existing experimental data.

Centromeric DNA varies greatly in size between species, ranging from small, genetically defined 125 base pair (bp) “point” centromeres in S. cerevisiae [3–9], to large “regional” centromeres in more complex eukaryotes, reaching up to several megabases in size [7].

Despite this diversity in size, the regional centromeres of monocentric (i.e. harboring a single centromere per chromosome) plants, insects, and mammals are typically composed of arrays of A/T (and sometimes G/C) nucleotide rich arrays known as satellites, which are interspersed with more complex DNA such as transposable elements [10–16]. Satellite repeats are not only found within the centromere core, but also at pericentric heterochromatin [17]. An alternative centromere configuration observed in some nematode, insect, and plant species, consists of centromeres spanning the entire length of a chromosome (i.e. holocentric [1]).

The occurrence of neocentromeres in humans, chickens, flies, and fungi [18–22], and the relatively frequent incidence of evolutionarily new centromeres (ENC) in horses, primates, and plants [23–25] demonstrates that new centromeres can form on non-centromeric DNA, suggesting that specific centromeric DNA sequences are not required for centromere function [8, 26, 27].

Interestingly, ENCs rapidly accumulate satellite repeats later in evolution [28, 29]. The mechanisms of satellite accumulation and the advantages that these sequences provide to centromere function are unknown, but the observation that neocentromeres display imperfect error-correction mechanisms raises the possibility that inherent properties of centromeric DNA are critical for optimal centromere function [30]. Perhaps the accumulation of satellites enables new centromeres to persist through evolution.

In addition to not being required to form functional centromeres, centromeric satellites are also not sufficient for centromere formation. For example, dicentric chromosomes contain two centromeric DNA regions but only one displays centromere activity [31]. Similarly, a subset of human neocentromeres have been identified on otherwise intact chromosomes harboring an inactivated endogenous centromere [24]. How these centromeres become inactivated remains elusive, but the process can involve heterochromatinization of one of the two centromeres [31–33].

While the functional contribution of centromeric repeats to centromere activity remains unclear, the presence of the histone H3 variant CENP-A (CENtromere Protein A; also called CenH3) [34, 35] as a hallmark of active centromeres is nearly universal [36], strongly supporting an epigenetic model for centromere determination [26]. Exceptions are kinetoplastids [36] and holocentric insects [37], which have been shown to employ CENP-A-independent mechanisms of kinetochore formation.

Neocentromeres lack centromeric DNA elements, but always contain CENP-A [22]. Conversely, inactive centromeres on dicentric chromosomes do not contain CENP-A [38–42]. Furthermore, the presence of CENP-A is sufficient for centromere activity in flies and humans, as mistargeted CENP-A can nucleate functional kinetochores, leading to severe mitotic errors [43–45].

Although CENP-A can associate with non-centromeric DNA in vivo and does not display a preference for human α-satellite DNA in vitro [24, 31], α-satellite arrays efficiently attract de novo CENP-A assembly when introduced into human HT1080 cells [46]. Similarly, in S. pombe, plasmid harboring a large portion of the centromere can be mitotically inherited [47]. Thus, some inherent properties of centromeric DNA, such as its transcriptional potential or the presence of DNA binding motifs for centromere proteins (such as CENP-B boxes in humans) may be optimal for CENP-A chromatin assembly (reviewed in [48]).

Centromeric deposition and structural properties of CENP-A

In most organisms, CENP-A is deposited in a DNA replication-independent manner [49, 50], unlike canonical histone H3 [51]. During DNA replication, the total amount of centromeric CENP-A is reduced by half [52, 53], with histone H3.1 and H3.3 becoming incorporated at the centromere as temporary placeholders [54]. To replenish CENP-A chromatin and maintain the centromere position through cell divisions, new CENP-A must be deposited at each cell cycle. The timing of new CENP-A loading has been elucidated for many organisms. In fission yeast, new CENP-A can be incorporated at centromeres during S-phase and G2 [55, 56]. In flies, CENP-A is replenished between metaphase and G1, depending on the type of tissue [53, 57, 58]. In humans, CENP-A is deposited during telophase/early G1 [52], and in plants CENP-A deposition occurs mainly during G2 [59].

While the specific mechanisms by which CENP-A nucleosomes replace the histone H3 placeholders are still unclear, studies suggest that transcription of the underlying centromeric DNA is involved in this exchange (reviewed in [48]).

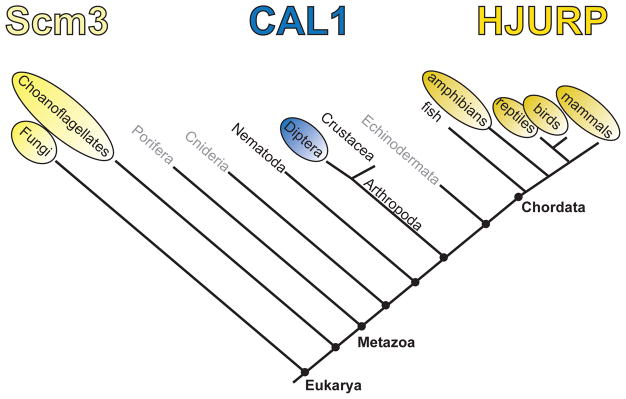

CENP-A deposition requires CENP-A-specific histone chaperones (or CENP-A assembly factors) [60–63]. CENP-A chaperones with common ancestry have been identified in lineages as divergent as yeast and humans (called Scm3 and HJURP, respectively; [64]). However, Drosophila employ an evolutionarily distinct CENP-A assembly factor called CAL1 [63], and no putative chaperones have yet been identified in plants, nematodes, fish, and other arthropods (Figure 1) [64].

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships of known CENP-A assembly factors.

Yellow circles represent taxa with Scm3/HJURP homologs. Blue circles indicate the birth of a novel CENP-A chaperone. The taxa lacking circles have no known CENP-A chaperone, while taxa in gray have yet to be examined.

The C-terminal histone-fold domain (HFD) of CENP-A is essential for CENP-A centromeric localization [65, 66], while the N-terminal tail is not required for localization during mitosis [67–69]. In yeast and humans, the region necessary for CENP-A targeting can be narrowed down even further to a domain encompassing loop 1 (L1) and the alpha 2 helix (α2) of the HFD, known as the CENP-A targeting domain (CATD) [68, 70]. Chimeras of canonical histone H3 containing the CATD of CENP-A (H3-CATD) localize to centromeres in yeast and humans [70, 71]. The CATD is the region of CENP-A that the HJURP/Scm3 family of chaperones specifically recognizes [reviewed in [2]]. However, this region is not sufficient to confer centromeric localization of H3 in Drosophila or Arabidopsis [72, 73], even though in Drosophila, L1 is essential for CENP-A targeting [69]. Additionally, CENP-A N-terminal tails have been shown to be critical for centromere establishment in budding yeast, for long-term centromere propagation and function in fission yeast and human cells [71, 74], and for fertility in plants [73].

CENP-C and CENP-N, centromere associated proteins that are part of the constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN) in vertebrates, recognize key structural features of the CENP-A nucleosome and provide a connection between centromeric chromatin and the outer kinetochore (reviewed in [2]).

Centromeric sequences evolve rapidly

Since specific centromeric DNA sequences are not essential for centromere function in most species, it is conceivable that these sequences would not be evolutionarily constrained. Consistent with this, centromeres contain some of the most rapidly evolving DNA sequences in eukaryotic genomes [75, 76]. Unequal crossing over during meiosis I, strand slippage during DNA replication, and the transposition of mobile DNA elements are thought to be responsible for variations in primary DNA sequence content and repeated arrays size [77, 78].

Although there are a few examples of conserved centromeric sequences, such as the CENP-B box in mouse and humans [79] and the related CentO and CentC satellite repeats from rice and maize [80], phylogenetic analysis of candidate centromeric repeats from 282 animal and plant species revealed very little sequence homology across over 50 million years of divergence [16]. Even between closely related species, the abundance and exact sequence of a specific centromeric satellite can vary. For example, in Drosophila melanogaster, the dodeca satellite (also known as Sat 6) is present at the centromere of chromosome 3. However, in its sister species Drosophila simulans, dodeca is present at the centromeres of both chromosomes 2 and 3 [81]. Likewise, Sat III (359-bp repeat) occupies the majority of the D. melanogaster X-chromosome centromere-proximal region, while it is completely absent from the D. simulans genome [82].

Thus, while the centromere region itself is essential and centromere function is conserved across species, the divergence of centromere sequences within and between species further supports the epigenetic model for centromere specification. However, increasing lines of evidence point to the potential involvement of centromere-derived RNAs and specific properties of centromeric DNA in centromere function, implicating a genetic component in centromere determination (reviewed in [2]).

Rapid Evolution of CENP-A

CENP-A is necessary for centromere function in all organisms containing it, and it has been shown to be sufficient for centromere formation in flies and humans (reviewed in [43–45]). However, like centromeric DNA, centromeric proteins and CENP-A in particular, are rapidly evolving [83–87]. Given the essential role of CENP-A in centromere function, the rapid evolution of CENP-A is paradoxical [88]. The divergence between CENP-A orthologs from distantly related species is so remarkable that it led to the hypothesis that CENP-A may have arisen multiple times throughout the course of evolution [89].

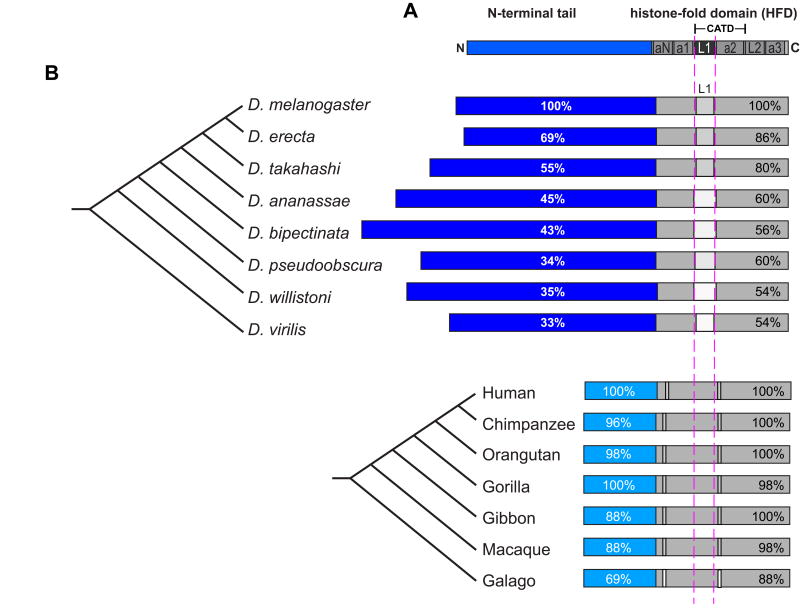

The histone fold domain (HFD; Figure 2A) of CENP-A is under positive selection in several lineages, including plants, flies, nematodes, and primates [83, 84, 86, 87, 90]. The CENP-A N-terminal tails (Figure 2A) are completely unconserved between taxa and are even diverged between closely related species (Figure 2B) [83, 86, 87, 90].

Figure 2. CENP-A protein domains and conservation.

A) Diagram showing the primary structure of CENP-A. The N-terminal tail is shown in blue, the histone-fold domain (HFD) is shown in gray. The CATD and L1 are indicated (see text for details). (B) Schematic of CENP-A orthologs from several Drosophila (top) and primate (bottom) species. Rapidly evolving residues in the C-terminal HFD are indicated by lighter boxes. Percentages indicate the identity of the N-terminal tails or HFD to Drosophila melanogaster or Homo sapiens. Note that L1 displays slight size variation.

In Drosophila, both the N-terminal tail and the HFD of CENP-A have been found to be evolving under positive selection (Figure 2B) [83, 85]. Despite the fact that Drosophila CENP-A evolves rapidly, its assembly factor, CAL1, evolves slowly in both of its critical domains: the region that interacts with CENP-A (N-terminus), and the region that interacts with CENP-C (C-terminus) [91, 92].

Rapid evolution of the N-terminal tail of CENP-A has been shown in several other species, including monkeyflower plants, Percid fishes, and Caenorhabditis [90, 93, 94]. In Brassicaceae plants, which include A. thaliana, and in the nematode Caenorhabditis, CENP-A was found to be rapidly evolving also within L1 [90, 95]. In contrast, CENP-A orthologs in rodents and grasses are under negative selection in both the HFD and the N-terminal tail [95].

While an initial analysis of CENP-A revealed no evidence of positive selection in human and chimp [95], a more comprehensive study of CENP-A from 16 primate species found 12 residues throughout the length of the protein that are rapidly evolving [86]. Half of the identified residues are within the HFD, none of which within L1, and the rest fall within in the N-terminal tail [86]. However, evolutionary changes in primate genes may be underestimated due to the small sample size, as well as the long generation time of these animals.

The centromere drive hypothesis

The rapid evolution of centromeric DNA and CENP-A (and other centromeric proteins) led to the proposal that these two components are evolving under genetic conflict, a hypothesis known as “centromere drive” [96, 97].

While meiosis is symmetrical in males, resulting in four gametes, in most plants and animals, females undergo asymmetric meiosis, where only one of the resulting four meiotic products survives and develops into the oocyte, while the remaining three turn into polar bodies or degenerate. This asymmetry can result in competition between homologous chromosomes for inclusion in the oocyte (a phenomenon known as meiotic drive) [98].

According to the centromere drive hypothesis, centromeric DNA acts as a selfish genetic element, exploiting asymmetric female meiosis to promote its preferential transmission to the egg. Centromere expansion (for example, by unequal crossing-over or the transposition of mobile DNA elements) would result in larger centromeres capable of attracting more kinetochore proteins and microtubules. Such asymmetry between two homologous centromeres, combined with the functional asymmetry in the egg’s spindle poles that determines cell fate, can lead to the more frequent transmission of one chromosome compared to its homolog, allowing it to sweep through a population along with possible hitchhiking detrimental mutations [99–101].

Centromere drive is expected to only occur in monocentric organisms, since holocentric organisms contain CENP-A nucleosomes dispersed throughout the genome, with no particular centromeric satellite capable of driving its own transmission. Consistent with this prediction, CENP-A orthologs from holocentric plants from the genus Luzula are not under positive selection, suggesting holocentrism allows for the evasion of centromere drive [102]. Another prediction of this model is that clades with symmetric meiosis, such as fungi, should display a lower frequency of adaptive evolution of CENP-A than those with asymmetric meiosis, and this indeed seems to be the case [101]. Inexplicably, CENP-A from C. elegans is rapidly evolving, even though this holocentric nematode does not require CENP-A for oocyte meiotic divisions [103].

In agreement with the centromere drive hypothesis, centromeres and centromere-linked loci can act as drivers during female meiosis. For example, Robertsonian fusions (Rb) segregate in a non-random fashion in mice, humans, and chickens [104–106]. In humans and chickens, the Robertsonian fusions are preferentially transmitted [104–106], while in mice, the rate of transmission depends on the karyotype of the mouse species [107]. Importantly, in mice this preferential segregation has been experimentally shown to correlate with centromere “strength” (i.e. to the relative amount of recruited kinetochore proteins and microtubule attachments; see box 1) [107]. Furthermore, in monkeyflowers, chromosomes containing the D locus, which is thought to be a duplication of a centromere region, are transmitted at a higher frequency (see box 2) [108].

Box 1. Non-random transmission of Robertsonian fusions supports centromere drive.

Studies in mice, humans, and chickens have shown that Robertsonian fusions (Rb) are non-randomly segregated during female meiosis. The formation of an Rb chromosome creates an asymmetric bivalent composed of a centric-fusion (containing a single centromere) paired with its two unfused counterparts (containing one centromere each; Figure). This asymmetry generates an opportunity for segregation bias [104, 107, 128, 129]. In the mouse M. musculus, which displays a predominantly telocentric karyotype, this bias favors the unfused chromosomes, the centromeres of which were shown to contain more CENP-A, Ndc80, and microtubules than the centromere of the Rb fusion [107]. In contrast, in humans and in mouse populations that have a primarily metacentric karyotype, the situation is reversed and the Robertsonian fusions attract more CENP-A, Ndc80, and microtubules thereby promoting their preferential transmission [107, 128] (Figure box 1). Meiotic drive of such chromosomal rearrangements provides the conceptual framework to explain the fixation of new karyotypes during evolution [128].

These data highlight how natural variations in centromere size correlates with centromere strength, and how this can result in drive. Importantly, studies that looked at male meiosis in mice and humans showed that heterozygosity for Rb chromosomes results in reduced fertility, which can lead to the selection for suppressors of this fitness cost [104, 130, 131].

Box 1 Figure.

Which centromere is stronger seems to depend on the background karyotype of the species. The two telocentric centromeres would be stronger in a mouse species with a predominantly telocentric karyotype (left), while the Rb fusion would be stronger when the karyotype is predominantly metacentric, such as in humans (right).

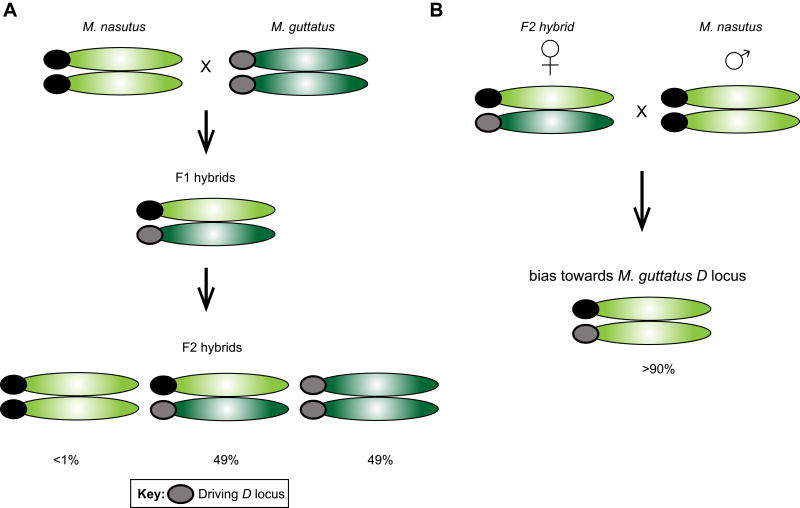

Box 2. Distorter locus at centromeres drives segregation in monkeyflowers.

Work in monkeyflowers provides additional support for the centromere drive hypothesis [109]. Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus nasutus are two closely related species of monkeyflower. Fishman and Willis [132] used linkage mapping to analyze M. guttatusnasutus × M. guttatus F2 hybrids, and determined that nearly half of the markers used in their study were inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion [132] (Figure I). Furthermore, nearly one-third of the markers in their study showed significantly distorted segregation ratios, and one of them (linkage group 11) showed nearly 100% segregation distortion [132,133]. This extreme rate of transmission bias is uncommon, which led to the dissection of the mechanisms behind this distorter (D) locus [108,114].

By repeated backcrossing of F2 hybrids to the original homozygous M. nasutus parental line, it was discovered that despite most of the genome being homozygous for M. nasutus alleles, the D locus remained over 90% heterozygous [114,134] (Figure I). This led the authors to conclude that the D locus could distort transmission ratios, and that heterozygosity at the D locus was critical for segregation distortion to occur, providing strong evidence for meiotic drive in female meiosis. Additionally, because of the extremely high transmission bias of the D locus, it was predicted that the D locus may in fact be the functional centromere of linkage group 11 [108,134], as only a centromere or centromere-linked locus can attain over 83% transmission bias via meiotic drive [134]. Fluorescence in situ hybridization showed that linkage group 11 is indeed centromere proximal [108]. Interestingly, after examining several strains of M. guttatus plants, it became apparent that the D locus has only recently begun to spread because it is still polymorphic, likely due to the male fitness cost and linked deleterious mutations that have prevented it from reaching fixation [135].

Box 2 Figure.

(A) Mimulus nasutus (maternal;dd) × Mimulus guttatus (paternal; DD) F2 hybrids were used to determine that inheritance of the D locus (marked by the oval) and other nearby loci deviated from the expected Mendelian segregation ratios (0:2:2 rather than the Mendelian 1:2:1 dd:Dd:DD). (B) By repeated backcrossing of F2 hybrids to the M. nasutus parental line (dd; paternal), it was discovered that despite most of the genome being homozygous for M. nasutus alleles, the D locus remained over 90% heterozygous. This suggested that the D locus from M. guttatus was being selected for. Adapted from with permission [34].

In female meiosis, centromere drive takes place at no cost to fertility. In contrast, in male meiosis an imbalance in centromere strength could lead to increased non-disjunction and meiotic stalling, resulting in either reduced fertility or sterility [109]. Decreased male fertility has indeed been observed in humans and mice with Rb fusions [104, 105, 110]. In mice, these fusions induce aneuploidy, chromosome misalignment, and apoptosis in spermatocytes [111], consistent with defects related to centromere imbalance. However, another study reported delayed pairing and genic incompatibility as the causes of infertility [110]. As for the D locus in monkeyflowers, heterozygous Dd plants have normal pollen count, while lower pollen count has been observed in homozygous plants (see box 2), likely due to a pleiotropic effect of meiotic pairing or to a hitchhiking of a deleterious allele [108]. More investigations are needed to understand if centromere imbalance is the cause of infertility in males carrying Rb chromosomes.

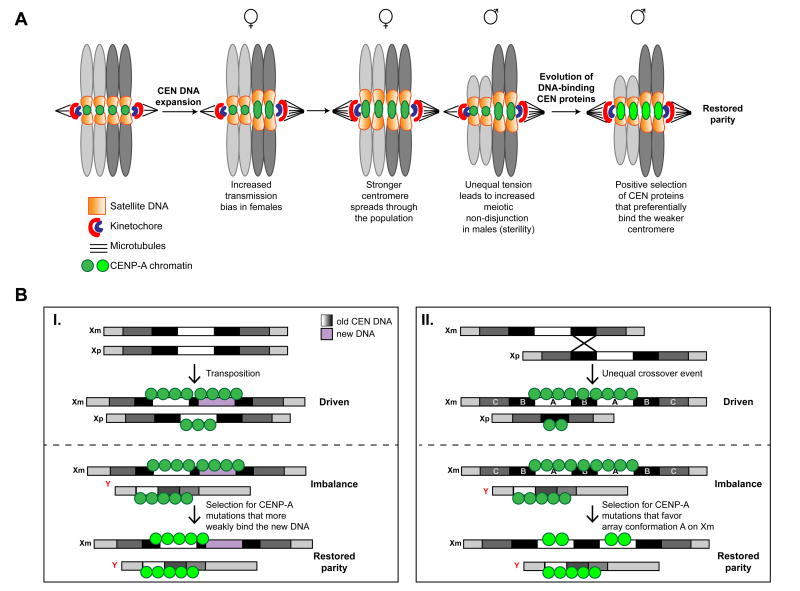

According to the centromere drive model, if centromere imbalance is deleterious in males, mutations able to restore meiotic parity would rapidly be selected for. Predictions based on the structural properties of H3 nucleosomes suggested that both the N-terminus of CENP-A and L1 make direct contact with DNA, raising the possibility that variability within these regions could affect histone/DNA-binding affinity. Such differential affinity is expected to direct how much CENP-A is recruited at certain DNA sequences, in turn modulating the size of the kinetochore and the number of microtubules. Collectively, these considerations led to the proposal that rapid changes in L1 or in the N-terminus of Drosophila CENP-A could become fixed because they have suppress centromere drive by reversing centromere imbalance (Figure 3A; [97, 109]).

Figure 3, Key Figure. Schematic of the centromere drive hypothesis.

A) The two-step model for centromere drive [109]. In the first step, satellite expansion results in a transmission bias during female meiosis, but non-disjunction during male meiosis, preventing the expansion from reaching fixation. In the second step, suppressor mutations in CENP-A or other centromeric (CEN) DNA binding protein are selected for to restore meiotic parity. These CENP-A alleles either increase microtubule binding to the weaker centromere (as shown), or reduce microtubule binding to the driven centromere (not shown). Either types of mechanisms are proposed to restore meiotic parity.

B) Possible models of how CENP-A alleles with altered DNA binding preferences could restore meiotic parity according to centromere drive [83].

B- I, centromere expansion occurs via the transposition of mobile DNA elements. Centromere balance is restored by the selection of CENP-A alleles that have increased preference for binding to the original centromeric sequences. B- II, centromere expansion occurs after an unequal crossover event during meiosis I. The expansion does not contain new DNA sequences, but may have altered periodicity of monomers due to the insertion, allowing for CENP-A mutations that preferentially interact with certain DNA conformations to be selected for.

Models of how CENP-A could suppress centromere drive

What kind of CENP-A alleles can reverse centromere drive? Only CENP-A alleles resulting in stronger affinity for the weaker centromere, or lower affinity for the expanded centromere, are expected to become fixed [109]. However, one aspect of this model that has not yet been well fleshed out is that changes within CENP-A that decrease its binding to centromeric satellites shared between both centromeres would not restore parity, and alleles affecting CENP-A’s binding to all centromeres would adversely affect chromosome segregation accuracy, and be eliminated from the population. Thus, the potential of certain CENP-A alleles to suppress drive and become fixed lies in their ability to influence the transmission of one specific centromere, and no other. In the case of centromere expansion via the transposition of mobile elements, which would bring new DNA sequences into an existing centromere, suppression of drive could be accomplished by changes within CENP-A that weaken the affinity for the new DNA (Figure 3B panel I). Alternatively, mutations in heterochromatin-associated proteins that enhance binding to the new satellites, out-competing CENP-A from the expanded centromere, could also act as suppressors [109].

However, in the case of centromere expansion events caused by an unequal crossover, which results in one chromosome having a sequence duplication and the homologous chromosome having an equivalent sequence deletion, the application of the centromere drive model is more difficult to envision. Under these circumstances, either the expanded centromere with the duplication or the smaller centromere with the deletion would have to contain distinct DNA elements onto which selection can act to restore centromere balance. For example, there could be selection for CENP-A mutations that favor a particular array size or pattern, resulting in a preference for one centromere over the other (Figure 3B panel II). Consistent with this possibility is the observation that CENP-A binding to higher-order repeat size and sequence variants in human Chromosome 17 results in differential centromere functionality [112].

Importantly, in either situation (Figure 3BI–II), modulating CENP-A binding could also be accomplished by CENP-A alleles that somehow alter CENP-A’s deposition by its chaperone [113], as discussed below.

While there is much biological evidence in support of the driving potential of centromeres [104, 107, 108, 114] and of the rapid evolution of CENP-A and centromeric DNA [16, 115], a causal relationship between these biological occurrences remains to be demonstrated. Different DNA sequences can exhibit different free-energies for the assembly of canonical nucleosomes [116]. Furthermore, the L1-DNA interaction could pose an energetic barrier during nucleosome assembly. Given that multiple DNA sequences compete for nucleosome formation during chromatin assembly, such an energetic barrier could result in a substantial preference for one DNA sequence over another [69]. However, it is difficult to reconcile such preferential DNA binding of CENP-A with the notion that centromeres are epigenetically determined, i.e. that CENP-A chromatin can form at many different genomic locations [26, 117] . Furthermore, biochemical evidence that CENP-A has preferences for certain DNA sequences over others is lacking.

In vivo tests in plants and in Drosophila provide some insight into the ability of divergent CENP-A proteins to bind heterologous centromeres, allowing CENP-A DNA-binding preferences to be assayed to a certain degree.

Tests for CENP-A localization at heterologous centromeres reveal divergence in the CENP-A deposition machinery

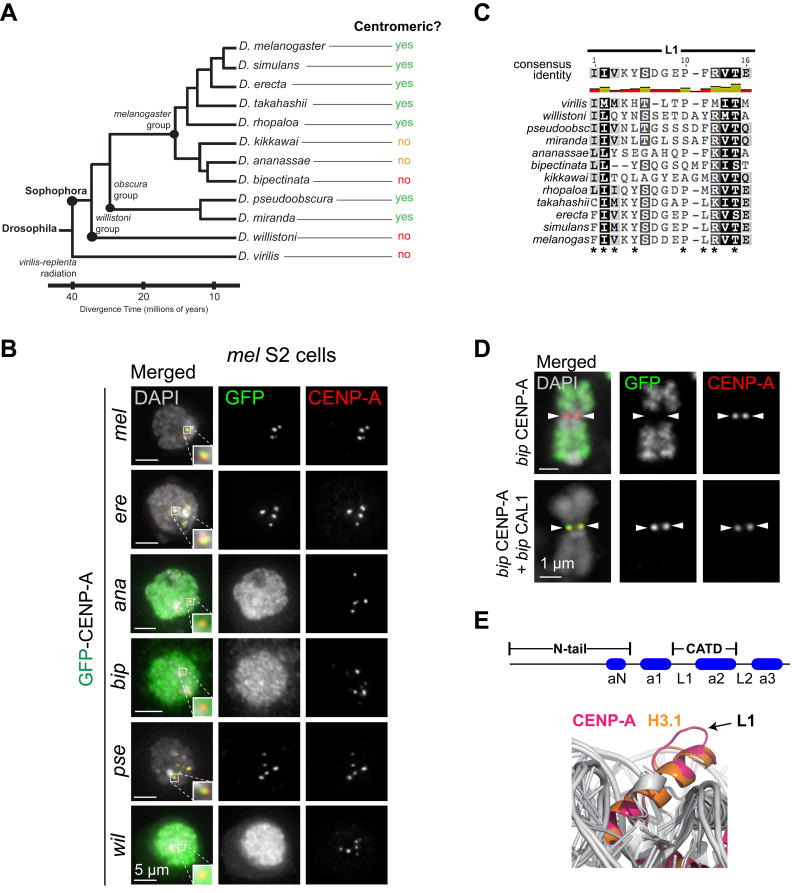

The centromere drive hypothesis predicts that evolutionarily divergent CENP-A orthologs may display different preferences for centromeric satellites. Support for such differential binding came from heterologous and chimeric CENP-A expression studies in Drosophila. CENP-A from Drosophila bipectinata (bip), which diverged from D. melanogaster (mel) only about 12 million years ago (mya), fails to localize to centromeres when expressed transiently in mel Kc cells (Figure 4A–B). Key amino acid changes in L1 of bip CENP-A were found to prevent bip CENP-A from localizing to mel centromeres (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Incompatibility between divergent CENP-A and the assembly factor CAL1 in Drosophila.

Incompatibility between divergent CENP-A and the assembly factor actor CAL1 in Drosophila. (A) Phylogenetic tree of the Drosophila species with indicated divergence time and phylogenetic grouping based on FlyBase [126]. The localization of divergent CENP-A orthologs in Drosophila melanogaster cells is indicated to the right. Green indicates complete centromeric localization, orange partial centromeric localization, red non-centromeric localization. (B) Immunofluorescence images of interphase D. melanogaster S2 cells transiently expressing GFP-tagged CENP-A orthologs from mel (D. melanogaster), ere (Drosophila erecta), ana (Drosophila ananassae), bip (Drosophila bipectinata), pse (Drosophila pseudoobscura), and wil (Drosophila willistoni). DAPI is shown in gray, GFP in green, and mel CENP-A in red. Zoomed insets show individual centromeres with merged colors. From [113]. (C) BLOSUM80 alignment of L1 from select species. Shading indicates percent similarity based on the BLOSUM80 score matrix [127]. Black indicates 100% similar, dark gray 80–100% similar, light gray 80–60% similar, white less than 60% similar. Stars indicate residues that have diverged in bip and are essential for CENP-A centromeric targeting [69]. Consensus sequence is shown above the alignment. Bar graph: green indicates highly conserved residues, gold somewhat conserved, and red unconserved. (D) Immunofluorescence images of metaphase chromosome spreads from S2 cells transiently expressing bip GFP–CENP-A alone (top), or bip GFP–CENP-A and bip CAL1 (bottom). DAPI is shown in gray, GFP in green, and mel CENP-A in red. White arrowheads indicate the position of the native mel centromere. (E) Comparison of CENP-A (magenta) and H3 (orange) nucleosome crystal structures [122]. The arrow indicates the protruding L1 region in CENP-A. Reproduced with permission from [122].

Despite the reported adaptive evolution of CENP-A in different species, the incompatibility between heterologous CENP-A and centromeres has not been observed outside of Drosophila. When CENP-A complementation assays were performed in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, untagged CENP-A orthologs from closely related species, such as A. arenosa (about 5 mya diverged [118]), as well as the more distant Brassica rapa (about 25 mya diverged), and even the very divergent Zea mays (almost 200 mya diverged [119]) were shown to functionally replace CENP-A in A. thaliana [120]. Although these complementation assays differ from experiments in which heterologous CENP-A proteins are expressed in the presence of the endogenous CENP-A protein (e.g. [69]), the data demonstrate that even CENP-A orthologs from highly divergent plants (i.e. monocots and dicots) can target the centromere of A. thaliana in mitosis and meiosis. Despite this, these plants showed compromised chromosome segregation and genome elimination in their progeny when crossed to wild type plants, suggesting the existence of critical species-specific adaptations of CENP-A [120].

Overall, these data indicate that if amino acid changes within CENP-A do indeed modulate its affinity for certain centromeric DNA sequences, this manifests itself in flies but not in plants, even though L1 is adaptively evolving in both lineages. However, some additional interactions could be responsible for the CENP-A/centromere incompatibility in Drosophila.

The Presence of species-matched CENP-A and CAL1 allows CENP-A deposition at heterologous centromeres

As discussed above, the inability of bip CENP-A to localize to mel centromeres was attributed to divergence between CENP-A and centromeric DNA. Specifically, it was proposed that L1 could mediate targeting of (CENP-A:H4)2 tetramers by preferential binding to certain DNAs. According to this interpretation, if different sequences compete for CENP-A binding, even slightly energetically favorable interactions would be expected to be driven to fixation within a population [69].

However, a recent study revealed that the impaired centromeric localization of bip CENP-A in mel cells can be rescued by the introduction of its species-matched assembly factor, bip CAL1, demonstrating the existence of an incompatibility between bip CENP-A and mel CAL1 that prevents the deposition of bip CENP-A at mel centromeres (Figure 4D). This work showed that the presence of an evolutionarily compatible CAL1 partner is the only requirement for centromeric targeting, even across large evolutionary distances where the centromeric DNA sequences have presumably diverged (Figure 4A; [113]).

The observation that divergent Drosophila CENP-A proteins can bind to divergent centromeres (as long as a compatible CAL1 is present) suggests two possible scenarios: either it argues against the centromere drive hypothesis, or it suggests that patterns of localization of CENP-A orthologs in heterologous expression experiments may not accurately recapitulate centromere drive.

We favor the latter possibility. We think that testing the ability of divergent CENP-As to localize to heterologous centromeres does not necessarily reflect whether or not these orthologs emerged to suppress centromere drive at some point in evolution. Furthermore, differential affinity for specific centromeric satellites may never become so pronounced as to impair centromere binding entirely, consistent with the promiscuity with which CENP-A is known to bind at a variety of non-centromeric DNAs (reviewed in [2]). Thus, these experiments do not properly mimic centromere drive in action and should not be used to prove or disprove centromere drive. Being able to measure different free energies associated with nucleosome wrapping using species-matched CENP-A and satellite DNA could provide some insights, but ultimately, a direct test of the centromere drive hypothesis will require the experimental isolation of L1 suppressors of a driven centromere, a very challenging feat.

However, the discovery of the role of CAL1 in centromere incompatibility in Drosophila raises the need for models of centromere conflict to be re-evaluated.

How is centromere integrity maintained in Drosophila in spite of CENP-A’s rapid evolution?

Domain-swap experiments between mel and bip proteins showed that the CENP-A–CAL1 interaction modules that need to be compatible for the successful centromeric localization of CENP-A orthologs at melheterologous centromeres are L1 of CENP-A and the first 40 amino acids of CAL1, which are part of the CENP-A binding domain of CAL1. Therefore, these domains must co-evolve to maintain centromere function [113].

Interestingly, the structure of the human CENP-A nucleosome revealed that, unlike L1 of histone H3, L1 of CENP-A protrudes outward from the nucleosome, providing a potential site for an interacting protein ([121–123]; Figure 4E). Although it is unknown whether Drosophila CENP-A L1 is also exposed, it likely behaves differently H3 L1 in the way it interacts with DNA because of its interaction with CAL1. The interaction with CAL1 is also expected to influence the evolution of L1.

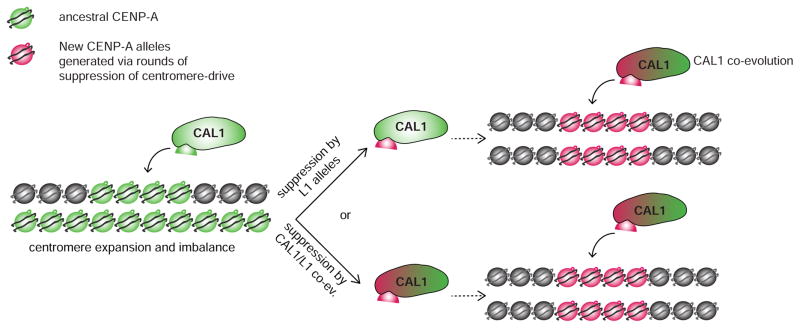

A prediction of the critical role L1 has in mediating Drosophila CENP-A recognition by CAL1 is that it should evolve to an optimum sequence and remain unchanged, rather than evolve rapidly [85]. Perhaps CAL1 has enough flexibility to accommodate the deposition of CENP-A orthologs with diverged L1 domains (e.g. mel CAL1 can deposit D. pseudoobscura CENP-A; Figure 4B), therefore enabling L1’s rapid evolution to suppress centromere drive. Alternatively, L1 mutations capable of modulating the levels of deposited CENP-A could suppress centromere drive [83]. However, as previously discussed, L1 mutations that impact CENP-A’s deposition by CAL1 at all centromeres would negatively impact centromere function without restoring balance, and would thus never become fixed. Only L1 alleles that alter CAL1-mediated CENP-A deposition at a specific centromere would be selected for, which would still require some level of centromere-specific binding mediated through DNA or RNA (Figure 3B) [124]. Whether L1 evolves to modulate DNA binding affinity for certain centromere configurations or sequences with CAL1 playing “catch up”, or whether L1 evolves to modulate deposition efficiency by CAL1 remains unclear. Regardless, CAL1 evolves in concert with L1, which is why incompatibility can arise between mismatched CAL1 and CENP-A proteins in heterologous expression experiments (Figure 5) [113].

Figure 5. Model for centromere evolution in Drosophila.

Centromere expansion in the ancestral species results in the selection of new CENP-A/CAL1 pairs that suppress drive. It is possible that new CENP-A L1 alleles themselves suppress drive though preferential interaction with DNA, and CAL1 subsequently co-evolves to maintain centromere identity (top). Alternatively, selection of L1 alleles might occur via the interaction with CAL1, resulting in changes in levels of CENP-A deposited [111] (bottom).

In light of these new data, the evolution of L1 under the centromere drive hypothesis needs to take into account the fact that CAL1 mediates CENP-A deposition through recognition of this region and that, in order to be driven to fixation, L1 alleles need to: 1) modulate CENP-A loading and/or satellite preference at the centromere of only one homolog, 2) not affect CENP-A loading at the other centromeres, and 3) not compromise the critical interaction with CAL1.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Although we are beginning to unravel the mechanisms of CENP-A assembly in a lineage harboring a rapidly evolving CENP-A, many questions remain unanswered. First, whether or not centromeric DNA is a contributing factor in CENP-A evolution is very hard to test experimentally, as previously discussed. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that transcription and centromeric RNAs may regulate centromere function (reviewed in [48]). Therefore, genetic changes affecting centromere-derived RNAs (for instance, from retroelements) could also drive CENP-A evolution [124]. However, there might be yet unexplored models to account for the rapid evolution of centromeric DNA and centromere-binding proteins.

Second, why the ancestral CENP-A assembly factor (Scm3) was lost in several lineages is unknown. The HJURP/Scm3 family of chaperones has only been identified in lineages where CENP-A does not display rapid evolution of L1 (e.g. fungi and mammals). Conversely, Drosophila (and possibly nematodes, fish, and plants [90, 94, 95]), where CENP-A L1 has been shown to be under positive selection, employ a distinct chaperone [83, 125]. CAL1 is co-evolving with Drosophila CENP-A, but it evolves at a slower rate than CENP-A [91]. We predict that permissive intermediate interactions allow these different modes of evolution. Perhaps CAL1 replaced the ancestral Scm3 chaperone in flies because of its ability to sustain the adaptive evolution of CENP-A. Alternatively, CENP-A could be rapidly evolving in flies because the birth of CAL1 relaxed structural constraints previously present on L1 in complex with Scm3.

Supplementary Material

Outstanding questions.

How does CAL1, which is evolving slowly, maintain the interaction with rapidly evolving CENP-A in Drosophila?

Why are CENP-A chaperones unconserved? Does the rapid evolution of CENP-A require the emergence of novel chaperones capable of accommodating these changes?

If CENP-A deposition is sequence-independent, how do new CENP-A alleles modulate differential satellite DNA affinity to suppress centromere drive?

Do centromere-derived RNAs play a role in centromere evolution?

Trends.

CENP-A and centromeric DNA have been proposed to co-evolve in an evolutionary tug-of-war known as centromere drive.

The amounts of centromeric and kinetochore proteins recruited to one centromere influence its likelihood to be transmitted via the female germline in mice.

It is unknown whether CENP-A can regulate the transmission rate of a centromere by modulating its binding preferences for certain DNA sequences.

CENP-A chaperones in flies have recently been implicated in this evolutionary arms race.

The failure of a subset of CENP-A orthologs from other species to localize to centromeres in D. melanogaster cells can be explained by an incompatibility with the CENP-A chaperone CAL1, rather than centromeric DNA.

The interaction between CAL1 and CENP-A is flexible, but the rapid evolution of CENP-A in flies has resulted in species-specific co-evolution of CAL1 to maintain centromere identity.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize for not being able to cite all the primary work due to space limitations. We are grateful to Shamoni Maheshwari, Luca Comai, Harmit Malik, and Rachel O’Neill for discussions on centromere evolution and suggestions on the manuscript. We thank members of the lab for editorial input. Work in the Mellone laboratory is supported by National Science Foundation award MCB1330667 and National Institutes of Health grant GM108829.

Glossary

- Neocentromere

A functional centromere that forms at a non-centromeric locus

- Evolutionarily New Centromere (ENC)

A centromere located at a novel chromosomal position relative to the ancestral centromere in that lineage. ENCs are devoid of satellite DNA and other centromeric repeats but contain CENP-A

- Dicentric chromosome

A chromosome containing two centromere regions, one of which is usually inactive, originated via the fusion of two chromosomes segments each containing a centromere

- Heterochromatinization

The transformation of euchromatin (active chromatin) into heterochromatin (inactive). This process usually involves epigenetic modification through the recruitment of histone methyl-transferases (HMTs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs)

- α-satellite DNA

171bp sequences arranged into a higher order repeat (HOR) structure found at the centromere region of higher primate species

- Positive selection

Refers to a type of selective pressure where the ratio of non-synonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions for a given gene is greater than 1 (dN/dS>1), indicating that certain mutations changing the amino acid composition are selected for. Also known as adaptive evolution

- Negative selection

Refers to a type of selective pressure where the ratio of nonsynonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions for a given gene is less than 1 (dN/dS<1), indicating that selection acts against changes within this protein. Also known as purifying selection

- Genetic conflict

When different genes or loci influence the same phenotype, and the transmission of one locus is increased due to its phenotypic effects being more favorable, causing a subsequent decrease in transmission of the other gene/locus. This conflict can be within an individual (intra-genomic) or between individuals (inter-genomic)

- Meiotic drive

The distortion from Mendelian ratios of allelic inheritance in heterozygotes during meiosis. Female meiotic drive, also known as chromosomal drive, occurs via competition among homologous chromosomes for inclusion in the egg, the only surviving product of meiosis. Male meiotic drive often acts post-meiotically, resulting in defective spermatids

- Selfish genetic element

A region of DNA that enhances its own transmission, often at the expense of the organism as a whole

- Robertsonian fusions

Also known as Robertsonian translocations, occur when two acrocentric or telocentric chromosomes (i.e. with centromeres at or near the end of the chromosome, respectively) fuse at their centromere, resulting in a large chromosome with a single centromere in the middle

- Co-evolution

When two proteins evolve in concert, possibly as a result of genetic conflict

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fukagawa T, Earnshaw WC. The Centromere: Chromatin Foundation for the Kinetochore Machinery. Dev Cell. 2014;30:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinley KL, Cheeseman IM. The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom KS, et al. Chromatin conformation of yeast centromeres. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1559–1568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.5.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke L, Carbon J. Isolation of a yeast centromere and construction of functional small circular chromosomes. Nature. 1980;287:504–509. doi: 10.1038/287504a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottarel G, et al. A 125-base-pair CEN6 DNA fragment is sufficient for complete meiotic and mitotic centromere functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3342–3349. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegemann JH, Fleig UN. The centromere of budding yeast. BioEssays News Rev Mol Cell Dev Biol. 1993;15:451–460. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pluta AF, et al. The centromere: hub of chromosomal activities. Science. 1995;270:1591–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoler S, et al. A mutation in CSE4, an essential gene encoding a novel chromatin-associated protein in yeast, causes chromosome nondisjunction and cell cycle arrest at mitosis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:573–586. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiens GR, Sorger PK. Centromeric chromatin and epigenetic effects in kinetochore assembly. Cell. 1998;93:313–316. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copenhaver GP, et al. Genetic definition and sequence analysis of Arabidopsis centromeres. Science. 1999;286:2468–2474. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudd MK, Willard HF. Analysis of the centromeric regions of the human genome assembly. Trends Genet TIG. 2004;20:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun X, et al. Sequence analysis of a functional Drosophila centromere. Genome Res. 2003;13:182–194. doi: 10.1101/gr.681703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H-R, et al. Chromatin immunoprecipitation cloning reveals rapid evolutionary patterns of centromeric DNA in Oryza species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11793–11798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503863102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardue ML, Gall JG. Chromosomal localization of mouse satellite DNA. Science. 1970;168:1356–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3937.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schueler MG, et al. Genomic and Genetic Definition of a Functional Human Centromere. Science. 2001;294:109–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1065042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melters DP, et al. Comparative analysis of tandem repeats from hundreds of species reveals unique insights into centromere evolution. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Flores I, Garrido-Ramos MA. The repetitive DNA content of eukaryotic genomes. Genome Dyn. 2012;7:1–28. doi: 10.1159/000337118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ketel C, et al. Neocentromeres form efficiently at multiple possible loci in Candida albicans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shang WH, et al. Chromosome engineering allows the efficient isolation of vertebrate neocentromeres. Dev Cell. 2013;24:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voullaire LE, et al. A functional marker centromere with no detectable alpha-satellite, satellite III, or CENP-B protein: activation of a latent centromere? Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:1153–1163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams BC, et al. Neocentromere activity of structurally acentric mini-chromosomes in Drosophila. Nat Genet. 1998;18:30–37. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall OJ, et al. Neocentromeres: new insights into centromere structure, disease development, and karyotype evolution. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:261–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wade CM, et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis, and population genetics of the domestic horse. Science. 2009;326:865–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1178158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocchi M, et al. Centromere repositioning in mammals. Heredity. 2012;108:59–67. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong Z, et al. Repeatless and repeat-based centromeres in potato: implications for centromere evolution. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3559–3574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karpen GH, Allshire RC. The case for epigenetic effects on centromere identity and function. Trends Genet TIG. 1997;13:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke L. Centromeres: proteins, protein complexes, and repeated domains at centromeres of simple eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:212–218. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amor DJ, Choo KHA. Neocentromeres: Role in Human Disease, Evolution, and Centromere Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:695–714. doi: 10.1086/342730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyler-Smith C, et al. Neocentromeres, the Y chromosome and centromere evolution. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 1998;6:65–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1017102926419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassett EA, et al. Epigenetic centromere specification directs aurora B accumulation but is insufficient to efficiently correct mitotic errors. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:177–185. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stimpson KM, et al. Dicentric chromosomes: unique models to study centromere function and inactivation. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2012;20:595–605. doi: 10.1007/s10577-012-9302-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan LL, et al. Human centromere repositioning within euchromatin after partial chromosome deletion. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10577-016-9536-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cech JN, Peichel CL. Centromere inactivation on a neo-Y fusion chromosome in threespine stickleback fish. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10577-016-9535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Earnshaw WC, Rothfield N. Identification of a family of human centromere proteins using autoimmune sera from patients with scleroderma. Chromosoma. 1985;91:313–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00328227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer DK, et al. A 17-kD centromere protein (CENP-A) copurifies with nucleosome core particles and with histones. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:805–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyoshi B, Gull K. Discovery of Unconventional Kinetochores in Kinetoplastids. Cell. 2014;156:1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drinnenberg IA, et al. Recurrent loss of CenH3 is associated with independent transitions to holocentricity in insects. eLife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Earnshaw WC, Migeon BR. Three related centromere proteins are absent from the inactive centromere of a stable isodicentric chromosome. Chromosoma. 1985;92:290–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00329812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Earnshaw WC, et al. Visualization of centromere proteins CENP-B and CENP-C on a stable dicentric chromosome in cytological spreads. Chromosoma. 1989;98:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00293329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merry DE, et al. Anti-kinetochore antibodies: Use as probes for inactive centromeres. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:425–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan BA, Schwartz S. Identification of centromeric antigens in dicentric robertsonian translocations: CENP-C and CENP-E are necessary components of functional centromeres. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2189–2197. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.12.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warburton PE, et al. Immunolocalization of CENP-A suggests a distinct nucleosome structure at the inner kinetochore plate of active centromeres. Curr Biol CB. 1997;7:901–904. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heun P, et al. Mislocalization of the Drosophila centromere-specific histone CID promotes formation of functional ectopic kinetochores. Dev Cell. 2006;10:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendiburo MJ, et al. Drosophila CENH3 Is Sufficient for Centromere Formation. Science. 2011;334:686–690. doi: 10.1126/science.1206880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Logsdon GA, et al. Both tails and the centromere targeting domain of CENP-A are required for centromere establishment. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:521–531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohzeki J, et al. Breaking the HAC Barrier: histone H3K9 acetyl/methyl balance regulates CENP-A assembly. EMBO J. 2012;31:2391–2402. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pidoux AL, Allshire RC. Kinetochore and heterochromatin domains of the fission yeast centromere. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2004;12:521–534. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036586.81775.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen C-C, Mellone BG. Chromatin assembly: Journey to the CENter of the chromosome. J Cell Biol. 2016;214:13–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201605005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shelby RD, et al. Chromatin assembly at kinetochores is uncoupled from DNA replication. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1113–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan B, Karpen G. Centromere identity in Drosophila is not determined in vivo by replication timing. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:683–690. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krude T. Chromatin: Nucleosome assembly during DNA replication. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1232–1234. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jansen LET, et al. Propagation of centromeric chromatin requires exit from mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:795–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mellone BG, et al. Assembly of Drosophila centromeric chromatin proteins during mitosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dunleavy EM, et al. H3.3 is deposited at centromeres in S phase as a placeholder for newly assembled CENP-A in G1 phase. Nucl Austin Tex. 2011;2:146–157. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.2.15211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi K, et al. Two distinct pathways responsible for the loading of CENP-A to centromeres in the fission yeast cell cycle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1614. 595-606-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takayama Y, et al. Biphasic incorporation of centromeric histone CENP-A in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:682–690. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuh M, et al. Incorporation of Drosophila CID/CENP-A and CENP-C into Centromeres during Early Embryonic Anaphase. Curr Biol. 2007;17:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunleavy EM, et al. The Cell Cycle Timing of Centromeric Chromatin Assembly in Drosophila Meiosis Is Distinct from Mitosis Yet Requires CAL1 and CENP-C. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lermontova I, et al. Loading of Arabidopsis centromeric histone CENH3 occurs mainly during G2 and requires the presence of the histone fold domain. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2443–2451. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Camahort R, et al. Scm3 Is Essential to Recruit the Histone H3 Variant Cse4 to Centromeres and to Maintain a Functional Kinetochore. Mol Cell. 2007;26:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foltz DR, et al. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams JS, et al. Fission yeast Scm3 mediates stable assembly of Cnp1/CENP-A into centromeric chromatin. Mol Cell. 2009;33:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C-C, et al. CAL1 is the Drosophila CENP-A assembly factor. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:313–329. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanchez-Pulido L, et al. Common ancestry of the CENP-A chaperones Scm3 and HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreno-Moreno O, et al. Proteolysis restricts localization of CID, the centromere-specific histone H3 variant of Drosophila, to centromeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6247–6255. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan KF, et al. Human CENP-A contains a histone H3 related histone fold domain that is required for targeting to the centromere. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:581–592. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Y, et al. The N Terminus of the Centromere H3-Like Protein Cse4p Performs an Essential Function Distinct from That of the Histone Fold Domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7037–7048. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.7037-7048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shelby RD, et al. Assembly of CENP-A into centromeric chromatin requires a cooperative array of nucleosomal DNA contact sites. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:501–513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vermaak D, et al. Centromere Targeting Element within the Histone Fold Domain of Cid. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7553–7561. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7553-7561.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Black BE, et al. Structural determinants for generating centromeric chromatin. Nature. 2004;430:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature02766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Black BE, et al. Centromere identity maintained by nucleosomes assembled with histone H3 containing the CENP-A targeting domain. Mol Cell. 2007;25:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moreno-Moreno O, et al. The F Box Protein Partner of Paired Regulates Stability of Drosophila Centromeric Histone H3, CenH3CID. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1488–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ravi M, et al. The rapidly evolving centromere-specific histone has stringent functional requirements in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2010;186:461–471. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fachinetti D, et al. A two-step mechanism for epigenetic specification of centromere identity and function. Nat Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncb2805. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Csink AK, Henikoff S. Something from nothing: the evolution and utility of satellite repeats. Trends Genet TIG. 1998;14:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murphy TD, Karpen GH. Centromeres take flight: alpha satellite and the quest for the human centromere. Cell. 1998;93:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Charlesworth B, et al. The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature. 1994;371:215–220. doi: 10.1038/371215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dover GA. Evolution of genetic redundancy for advanced players. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:902–910. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90012-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Earnshaw WC, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNA for CENP-B, the major human centromere autoantigen. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:817–829. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng Z, et al. Functional rice centromeres are marked by a satellite repeat and a centromere-specific retrotransposon. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1691–1704. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ferree PM, Prasad S. How can satellite DNA divergence cause reproductive isolation? Let us count the chromosomal ways. Genet Res Int. 2012;2012:430136. doi: 10.1155/2012/430136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ferree PM, Barbash DA. Species-specific heterochromatin prevents mitotic chromosome segregation to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Malik HS, Henikoff S. Adaptive evolution of Cid, a centromere-specific histone in Drosophila. Genetics. 2001;157:1293–1298. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cooper JL, Henikoff S. Adaptive evolution of the histone fold domain in centromeric histones. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1712–1718. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malik HS, et al. Recurrent evolution of DNA-binding motifs in the Drosophila centromeric histone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1449–1454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032664299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schueler MG, et al. Adaptive evolution of foundation kinetochore proteins in primates. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1585–1597. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Talbert PB, et al. Centromeric localization and adaptive evolution of an Arabidopsis histone H3 variant. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1053–1066. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henikoff S, et al. The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science. 2001;293:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1062939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malik HS, Henikoff S. Phylogenomics of the nucleosome. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:882–891. doi: 10.1038/nsb996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zedek F, Bureš P. Evidence for centromere drive in the holocentric chromosomes of Caenorhabditis. PloS One. 2012;7:e30496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Phansalkar R, et al. Evolutionary insights into the role of the essential centromere protein CAL1 in Drosophila. Chromosome Res Int J Mol Supramol Evol Asp Chromosome Biol. 2012;20:493–504. doi: 10.1007/s10577-012-9299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schittenhelm RB, et al. Detrimental incorporation of excess Cenp-A/Cid and Cenp-C into Drosophila centromeres is prevented by limiting amounts of the bridging factor Cal1. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3768–3779. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Finseth FR, et al. Duplication and Adaptive Evolution of a Key Centromeric Protein in Mimulus, a Genus with Female Meiotic Drive. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:2694–2706. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abbey HNA, Kral LG. Adaptive Evolution of CENP-A in Percid Fishes. Genes. 2015;6:662–671. doi: 10.3390/genes6030662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Talbert PB, et al. Adaptive evolution of centromere proteins in plants and animals. J Biol. 2004;3:18. doi: 10.1186/jbiol11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zwick ME, et al. Genetic variation in rates of nondisjunction: association of two naturally occurring polymorphisms in the chromokinesin nod with increased rates of nondisjunction in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;152:1605–1614. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Henikoff S, Malik HS. Centromeres: selfish drivers. Nature. 2002;417:227. doi: 10.1038/417227a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sandler L, Novitski E. Meiotic Drive as an Evolutionary Force. Am Nat. 1957;91:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Malik HS, Bayes JJ. Genetic conflicts during meiosis and the evolutionary origins of centromere complexity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:569–573. doi: 10.1042/BST0340569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Sapienza C. Nonrandom segregation during meiosis: the unfairness of females. Mamm Genome Off J Int Mamm Genome Soc. 2001;12:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s003350040003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zedek F, Bureš P. CenH3 evolution reflects meiotic symmetry as predicted by the centromere drive model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33308. doi: 10.1038/srep33308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zedek F, Bureš P. Absence of positive selection on CenH3 in Luzula suggests that holokinetic chromosomes may suppress centromere drive. Ann Bot. 2016 doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Monen J, et al. Differential role of CENP-A in the segregation of holocentric C. elegans chromosomes during meiosis and mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1248–1255. doi: 10.1038/ncb1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Daniel A. Distortion of female meiotic segregation and reduced male fertility in human Robertsonian translocations: consistent with the centromere model of co-evolving centromere DNA/centromeric histone (CENP-A) Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:450–452. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Sapienza C. Transmission ratio distortion in offspring of heterozygous female carriers of Robertsonian translocations. Hum Genet. 2001;108:31–36. doi: 10.1007/s004390000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dinkel B, et al. Gametic Products Transmitted by Chickens Heterozygous for Chromosomal Rearrangements. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1979;23:124–136. doi: 10.1159/000131313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chmátal L, et al. Centromere Strength Provides the Cell Biological Basis for Meiotic Drive and Karyotype Evolution in Mice. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2295–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fishman L, Saunders A. Centromere-associated female meiotic drive entails male fitness costs in monkeyflowers. Science. 2008;322:1559–1562. doi: 10.1126/science.1161406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Malik HS. The centromere drive hypothesis: a simple basis for centromere complexity. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2009;48:33–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00182-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wallace BMN, et al. The effect of multiple simple Robertsonian heterozygosity on chromosome pairing and fertility of wild-stock house mice (Mus musculus domesticus) Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;96:276–286. doi: 10.1159/000063054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Eaker S, et al. Evidence for meiotic spindle checkpoint from analysis of spermatocytes from Robertsonian-chromosome heterozygous mice. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2953–2965. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aldrup-MacDonald ME, et al. Genomic variation within alpha satellite DNA influences centromere location on human chromosomes with metastable epialleles. Genome Res. 2016 doi: 10.1101/gr.206706.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rosin L, Mellone BG. Co-evolving CENP-A and CAL1 Domains Mediate Centromeric CENP-A Deposition across Drosophila Species. Dev Cell. 2016;37:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fishman L, Willis JH. A novel meiotic drive locus almost completely distorts segregation in mimulus (monkeyflower) hybrids. Genetics. 2005;169:347–353. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Malik HS, Henikoff S. Major evolutionary transitions in centromere complexity. Cell. 2009;138:1067–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Thåström A, et al. Sequence motifs and free energies of selected natural and non-natural nucleosome positioning DNA sequences. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:213–229. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Buscaino A, et al. Building centromeres: home sweet home or a nomadic existence? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hohmann N, et al. A Time-Calibrated Road Map of Brassicaceae Species Radiation and Evolutionary History. Plant Cell. 2015;27:2770–2784. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zeng L, et al. Resolution of deep angiosperm phylogeny using conserved nuclear genes and estimates of early divergence times. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4956. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Maheshwari S, et al. Naturally occurring differences in CENH3 affect chromosome segregation in zygotic mitosis of hybrids. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sekulic N, et al. The structure of (CENP-A-H4)(2) reveals physical features that mark centromeres. Nature. 2010;467:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature09323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tachiwana H, et al. Crystal structure of the human centromeric nucleosome containing CENP-A. Nature. 2011;476:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tachiwana H, et al. Comparison between the CENP-A and histone H3 structures in nucleosomes. Nucl Austin Tex. 2012;3:6–11. doi: 10.4161/nucl.18372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brown JD, O’Neill RJ. Chromosomes, conflict, and epigenetics: chromosomal speciation revisited. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2010;11:291–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen CC, et al. A role for the CAL1-partner Modulo in centromere integrity and accurate chromosome segregation in Drosophila. PloS One. 2012;7:e45094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Attrill H, et al. FlyBase: establishing a Gene Group resource for Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Henikoff S, Henikoff JG. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Sapienza C. Female meiosis drives karyotypic evolution in mammals. Genetics. 2001;159:1179–1189. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.3.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wyttenbach A, et al. Meiotic drive favors Robertsonian metacentric chromosomes in the common shrew (Sorex araneus, Insectivora, mammalia) Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;83:199–206. doi: 10.1159/000015178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hauffe HC, Searle JB. Chromosomal heterozygosity and fertility in house mice (Mus musculus domesticus) from Northern Italy. Genetics. 1998;150:1143–1154. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.3.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ross BD, Malik HS. Genetic Conflicts: Stronger Centromeres Win Tug-of-War in Female Meiosis. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R966–R968. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fishman L, et al. A Genetic Map in the Mimulus guttatus Species Complex Reveals Transmission Ratio Distortion due to Heterospecific Interactions. Genetics. 2001;159:1701–1716. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fishman L, Willis JH. Evidence for dobzhansky-muller incompatibilites contributing to the sterility of hybrids between mimulus guttatus and m. nasutus. Evolution. 2001;55:1932–1942. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Malik HS. Mimulus finds centromeres in the driver’s seat. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Charlesworth D. Evolution. Competitive centromeres. Science. 2008;322:1484–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1167573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.