Abstract

Given the rise in depression disorders in adolescence, it is important to develop and study depression prevention programs for this age group. The current study examined the efficacy of Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST), a group prevention program for adolescent depression, in comparison to group programs that are typically delivered in school settings. In this indicated prevention trial, 186 adolescents with elevated depression symptoms were randomized to receive IPT-AST delivered by research staff or group counseling (GC) delivered by school counselors. Hierarchical linear modeling examined differences in rates of change in depressive symptoms and overall functioning from baseline to the 6-month follow-up assessment. Cox regression compared rates of depression diagnoses. Adolescents in IPT-AST showed significantly greater improvements in self-reported depressive symptoms and evaluator-rated overall functioning than GC adolescents from baseline to the 6-month follow-up. However, there were no significant differences between the two conditions in onset of depression diagnoses. Although both intervention conditions demonstrated significant improvements in depressive symptoms and overall functioning, results indicate that IPT-AST has modest benefits over groups run by school counselors which were matched on frequency and duration of sessions. In particular, IPT-AST outperformed GC in reduction of depressive symptoms and improvements in overall functioning. These findings point to the clinical utility of this depression prevention program, at least in the short-term. Additional follow-up is needed to determine the long-term effects of IPT-AST, relative to GC, particularly in preventing depression onset.

Keywords: Prevention, Adolescents, Depression

Depression is a serious mental health concern. Current treatments can only reduce a third of the population burden associated with depression, given the large number of new cases and the delays in accessing effective treatment (Chisholm et al. 2004). This has led to a growing interest in the development of depression prevention interventions which have the ability to reach a larger number of individuals and may reduce the burden of depression at both population and individual levels. Given that depressive symptoms and disorders rise dramatically during adolescence, and adolescent-onset depression increases risk for recurrence of depression in adulthood (Rutter et al. 2006), adolescence is an opportune time to deliver preventive interventions. Thus, it is important to develop programs for this age group, particularly interventions that address key risk factors for depression and can be delivered in schools where youth are most likely to receive services.

This paper presents initial findings from an efficacy study of a school-based indicated preventive intervention that targets interpersonal vulnerabilities for depression, Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST; Young and Mufson 2010). Schools provide an optimal venue for prevention due to the ease of identifying youth, the ability to provide the intervention on site, and the relative lack of stigma of school-based interventions (Masia-Warner et al. 2006). An interpersonally oriented depression prevention program may be particularly relevant for schools as social, interpersonal, and family problems are the most commonly occurring psychosocial problems in schools and consume the most resources (Foster et al. 2005). We focused on early adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms as these youth experience significant impairment (Lewinsohn et al. 2000). and because elevated symptoms in adolescence place individuals at increased risk for depression in adulthood (Fergusson et al. 2005). To date, a number of prevention programs for youth with subthreshold depression have been developed and tested based primarily on cognitive-behavioral (CB) approaches. Meta-analyses support the efficacy of these indicated prevention programs, although the effect sizes are generally small (Merry et al. 2011; Stice et al. 2009). We developed IPT-AST as an alternative to existing CB prevention programs to help address the need for novel preventive approaches that can decrease the disease burden associated with depression.

IPT-AST, an adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy (Mufson et al. 2004; Weissman et al. 2000). addresses different risk factors than CB approaches which target cognitive and behavioral vulnerabilities. IPT-AST is based on interpersonal theories of depression which posit that certain individuals possess interpersonal risk factors, such as maladaptive interpersonal behaviors and/or chronic impairment in interpersonal relationships, which make them particularly susceptible to the deleterious impact of interpersonal stressors on depression (e.g., Rudolph et al. 2008). The relation between interpersonal vulnerability factors and depression is reciprocal and transactional, with interpersonal difficulties preceding depressive symptoms which further contribute to these interpersonal problems (Garber 2006; Rudolph et al. 2008; Stice et al. 2004). IPT-AST aims to decrease interpersonal conflict and increase social support, two interpersonal factors which have been linked prospectively to adolescent depression (e.g., Allen et al. 2006; Brendgen et al. 2005; Sheeber et al. 2007; Stice et al. 2004). Therefore, IPT-AST differs from CB programs in its primary focus on modifying interpersonal interactions that contribute to negative emotions, whereas CB prevention programs mainly target cognitions and behaviors that impact one's feelings.

To date, we have conducted two small randomized controlled trials examining the efficacy of IPT-AST as compared to usual school counseling in adolescents with elevated depression. IPT-AST led to significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms and overall functioning in both trials, with medium to large effects (effect sizes range from 0.51 to 1.52 in the two studies). IPT-AST also led to significant reductions in depression diagnoses in the 6 months following the intervention (Young et al. 2006, 2010). These initial findings suggest that IPT-AST is a promising intervention. The current study builds on prior IPT-AST research and the larger prevention literature in a number of ways. First, prior indicated IPT-AST studies included predominately inner city, Hispanic youth from low socioeconomic backgrounds. While we believe that this is a unique strength, since minority youth have been underrepresented in depression prevention trials, the current study sought to determine the generalizability of effects in a larger and more diverse sample. Second, within an indicated prevention context, IPT-AST has only been compared to individual school counseling delivered at a lower frequency than a weekly group intervention. This is a step above many prevention studies, which have not included an active control condition, but prevents conclusions about whether findings are attributable to specific effects of IPT-AST or non-specific effects of being in a group for a certain number of sessions.

There is a growing recognition within the prevention literature of the need to include active control conditions to better estimate effect sizes and to determine specificity of effects. Meta-analyses report smaller and oftentimes non-significant effects in studies with active control conditions (e.g., Cuijpers et al. 2008; Merry et al. 2011). as have individual prevention trials (e.g., Gillham et al. 2007; Stice et al. 2008, 2010). The current study, which compares IPT-AST to group counseling (GC) as delivered by school counselors, is one of the first studies to compare a structured depression prevention program to groups implemented by personnel already providing similar services in schools, an ecologically valid control condition. In addition, GC groups were enhanced to match IPT-AST on frequency and duration of sessions, providing a rigorous test of dosage. Therefore, this study answers the important question of whether IPT-AST offers benefits above and beyond other groups run in schools and has implications for whether schools should adopt this specific depression prevention program as compared to groups that can be implemented without additional training, supervision, or fidelity monitoring.

This paper presents initial data on the main outcomes (depressive symptoms, overall functioning, and depression diagnoses) from this randomized controlled trial up to the 6-month follow-up evaluation. The first aim of the study was to examine the impact of IPT-AST on depressive symptoms and overall functioning. We hypothesized that there would be significantly different rates of change in depressive symptoms and overall functioning, with IPT-AST youth experiencing greater improvements than GC youth. The second aim of the study was to examine whether the rates of depression diagnoses differed in the two intervention conditions. We hypothesized that fewer youth in IPT-AST than in GC would experience a depression diagnosis.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 186 adolescents who were enrolled in the 7th to 10th grades at participating middle and high schools. The average age was 14.01 years (SD=1.22), and the sample was 66.7 % female. A third of the adolescents were racial minorities (19.9 % African American, 4.3 % Asian, and 8.1 % who specified other or mixed race); 38.2 % were Hispanic and 38.2 % were White non-minority, non-Hispanic (see Table 1). Regarding gross income, there was a wide range represented as follows: 17.3 % of families earned less than $25,000, 38.4 % earned between $25,000 and $90, 000, and 44.3 % earned more than $90,000.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

| GC (N=91) | IPT-AST (N=95) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 13.42 (1.18) | 13.56 (1.28) | 0.43 |

| Female (%) | 60 (65.9 %) | 64 (67.4 %) | 0.84 |

| Racial minority (%) | 29 (31.9 %) | 31 (32.6 %) | 0.91 |

| Hispanic (%) | 36 (39.6 %) | 35 (36.8 %) | 0.70 |

| White, non-minority, non-Hispanic (%) | 36 (39.6 %) | 35 (36.8 %) | 0.70 |

| Clinical measures | |||

| Screening CES-D, mean (SD) | 24.41 (6.88) | 23.14 (6.37) | 0.19 |

| Baseline CES-D, mean (SD) | 15.07 (8.65) | 15.51 (8.52) | 0.73 |

| Baseline CGAS, mean (SD) | 67.55 (5.24) | 67.44 (4.98) | 0.89 |

| Current diagnoses | |||

| No diagnosis (%) | 71 (78.0 %) | 73 (76.8 %) | 0.85 |

| Depressive disorder NOS (%) | 11 (12.1 %) | 6 (6.3 %) | 0.21 |

| Social phobia (%) | 7 (7.7 %) | 2 (2.1 %) | 0.09 |

| GAD (%) | 2 (2.2 %) | 3 (3.2 %) | 1.00 |

| OCD (%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (1.1 %) | 1.00 |

| Specific phobia (%) | 1 (1.1 %) | 3 (3.2 %) | 0.62 |

| PTSD (%) | 1 (1.1 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.49 |

| ADHD (%) | 4 (4.4 %) | 5 (5.3 %) | 1.00 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder (%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 1 (1.1 %) | 1.00 |

| Tic disorder (%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 2 (2.1 %) | 0.50 |

| Enuresis (%) | 2 (2.2 %) | 0 (0.0 %) | 0.24 |

| Pervasive developmental disorder (%) | 0 (0.0 %) | 3 (3.2 %) | 0.25 |

Procedures

Schools in central New Jersey were approached about the study through outreach, letters, and brochures; 10 schools agreed to participate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and by school administrators and boards of participating districts. Recruitment, outcomes, and adverse events were monitored by a data and safety monitoring board.

Adolescents with elevated symptoms of depression were identified through a two-stage screening procedure. First, letters and consent forms were sent home to families describing the depression screening. On the day of the screening, youth whose parents consented to the screening were informed of the procedures, and those who wanted to participate signed a screening assent form. From a total of 9123 students, 2923 (32.0 %) returned parental consent forms, provided assent, and completed the depression screening. Screening rates ranged from 14.1 to 57.1 % across the 10 schools. The screening consisted of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977), a 20-item measure that assesses depressive symptoms over the past week. Adolescents with a CES-D score of 16 or higher were eligible to be approached for the prevention project. As in our prior studies, we used the adult criterion of a score equal to or greater than 16 because we wanted to identify as many adolescents as possible with elevated depressive symptoms. The average CES-D score of the 2923 youth screened was 10.00 (SD=9.51); 593 youth had an elevated CES-D score and were eligible to be approached about the prevention study. These adolescents and their parents were contacted by research staff to describe the prevention project. Eighty families did not respond to multiple attempts to discuss the project. Among the families reached, the most common reasons for refusing participation were disinterest on the part of the adolescent and/ or parent (38.0 %) and lack of perceived need (20.0 %). Interested families met with the research team at school to learn about the project and provided consent and assent. Almost half of the youth with elevated CES-D scores agreed to participate in an eligibility evaluation and the prevention program if eligible (N=271). There were no significant differences between youth who consented to participate and those who did not on age (13.59 years vs. 13.61 years; t(591)= 0.20), gender (62.4 % female vs. 63.4 % female; χ2=0.06), or CES-D score (24.65 vs. 23.99; t(591)=−1.16).

Adolescents who consented to the prevention project completed the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al. 1997) as the second stage of the eligibility process. These evaluations occurred on average 4.77 weeks (SD=1.77) after the screening. Youth were eligible if they had at least two subthreshold or threshold depression symptoms on the K-SADS-PL, one of which was depressed mood, irritability, or anhedonia. Evidence of subthreshold depression on the K-SADS-PL was required to ensure that participating youth were experiencing sustained subthreshold depression and not simply elevated symptoms that could be better attributed to another emotional or physical problem. Twenty-four youth were excluded because they did not endorse at least two subthreshold or threshold symptoms. Adolescents were also excluded from the study if they had a current diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia (n=36), bipolar disorder (n= 0), psychosis (n=1), substance abuse (n=0), or conduct disorder (n=3). Youth were also excluded if they endorsed significant suicidal ideation or non-suicidal self-injury (n= 11), or had significant cognitive or language impairments (n= 1). Youth with these comorbid conditions were excluded because they had more significant pathology than could be addressed in a prevention program, and so were provided with referrals in the community. Eligible adolescents completed the remaining measures at a baseline evaluation that occurred on average 2.32 weeks (SD=1.51) after the eligibility evaluation and prior to randomization.

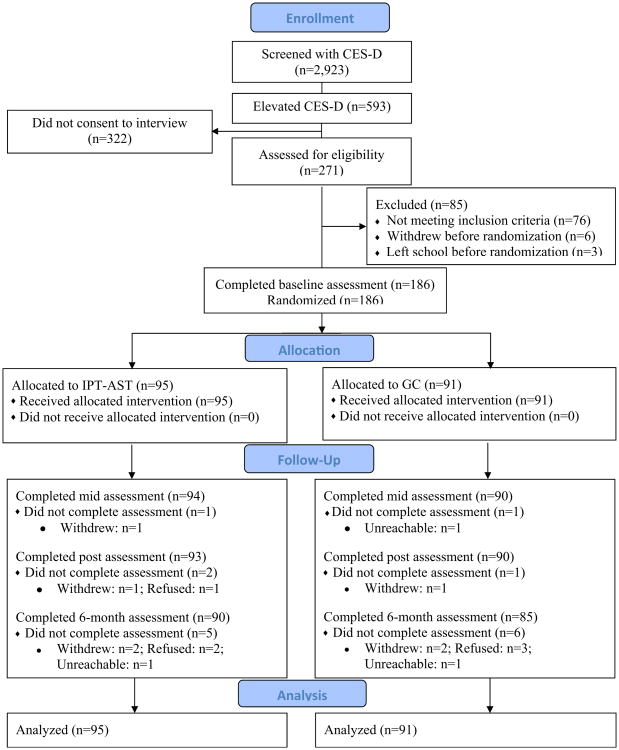

The 186 eligible adolescents were randomly assigned to receive IPT-AST or GC. Within each school, we stratified on gender and then used a computer-generated random number sequence to assign youth to IPT-AST (n=95) or GC (n=91). All participants, regardless of their degree of future participation, were considered part of the study once they were randomized (an intent-to-treat design). Details of the flow of participants are provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Participant flow chart.

Intervention Conditions

IPT-AST IPT-AST has two individual pre-group sessions (30–50 min each), eight group sessions (45–90 min each), and an individual mid-group session that the parents are invited to attend (30–50 min). During pre-group sessions, the leader provides a framework for the group and reviews the teen's current relationships to identify interpersonal goals for group. These goals might include reducing conflict with family members or peers and/or increasing support that one receives from relationships. In the first two group sessions, youth learn about the symptoms of depression, discuss the relationship between feelings and interpersonal interactions, and participate in activities that help them understand the impact of their communication on others. Youth are introduced to different communication and interpersonal strategies in the third group, such as using “I statements” and finding the right time to have a conversation, and practice these skills by role-playing hypothetical situations. In sessions four through six, youth apply these interpersonal strategies to their own relationships with the goal of reducing conflict and building support from others. Finally, in the remaining sessions, the group reviews the strategies learned and identifies ways to continue using the skills.

Mid-way through group, there is an individual session where the adolescent applies the communication and interpersonal strategies to a particular relationship related to his or her goals for the group. The adolescent is encouraged to have a parent attends part of the mid-group session so she/he can practice using the interpersonal skills in a conversation with a parent to address a parent-related issue, or to get support from a parent to address other interpersonal goals. In addition, in this study, we added four individual booster sessions in the 6 months following group. These booster sessions, lasting between 15 and 50 min, are used to discuss the application of the strategies to current life stressors to solidify the adolescent's skills and address interpersonal problems and increase support to prevent the worsening of depression symptoms.

There were 18 IPT-AST groups, ranging in size from three to seven youth. Ten groups were implemented during the school day; eight were conducted after school. The individual sessions (pre-group, mid-group, and booster sessions) occurred primarily during school day. All groups had two leaders. Of the 12 IPT-AST leaders in the study, three had clinical psychology doctoral degrees, and nine were clinical psychology graduate students. Prior psychotherapy experience of IPT-AST leaders ranged from 1 to 10 years, with an average of 3.58 years. Leaders read the IPT-AST manual and attended a 1-day workshop focused on core techniques of the model before initiating the groups. All IPT-AST sessions were audio recorded. An experienced IPT-AST clinician listened to each group session and half of the individual sessions as part of weekly supervision and to rate session fidelity using the IPT-AST supervision checklist (Young and Mufson 2005). Across all sessions coded, 98.5 % of the techniques were delivered with fidelity and were given a rating of satisfactory (49.0 %) or superior (49.5 %) for technique delivery. A global competency rating was given to each group leader at the end of the group: 8.8 % of the leaders received a rating of satisfactory, 41.2 % good, and 50.0 % excellent.

Group Counseling

Group counseling (GC) was meant to reflect the variety of groups run in schools, while being enhanced to match IPT-AST on frequency and duration of sessions. GC differed from usual practices in these schools in a number of ways. There was considerable variability across schools in the prior use of group programs. This was the first time groups were being conducted in some schools. In schools that had active group programs, groups prior to the start of the study had shorter and more infrequent sessions than GC as delivered in the study. GC consisted of a pre-group session (15–45 min), eight weekly group sessions (with sessions lasting as long as the IPT-AST groups in that school; 45–90 min), a mid-group session (15– 45 min), and four booster sessions (15–45 min). Because we wanted the content of GC to approximate normal practices in schools when someone is identified as potentially benefiting from a group program, we did not provide any limitations on the content or techniques used in GC. Midway through the group and at the end of group, counselors completed the Therapy Procedures Checklist (TPC; Weersing et al. 2002) to report on their use of therapeutic techniques in the group. The TPC assesses techniques from four therapeutic models: cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, and family. In 12 groups, cognitive techniques were employed most frequently; in four groups, psychodynamic techniques were used most.

There were 16 GC groups, ranging in size from two to eight youth. Most groups were run by a single group leader. Twelve GC groups were conducted during the school day; four groups occurred at school after school hours. The majority of counselors held Master's degrees in education, counseling, or a related field; five were graduate students, and one was a doctoral level psychologist. Prior counseling experience ranged from less than 1 to 30 years, with an average of 9.50 years, significantly greater than IPT-AST leaders, t(21.8)=2.63, p<0.05.

Assessments

This article focuses on results for the study's primary outcome variables: depressive symptoms, overall functioning, and depression disorders. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the CES-D, a widely used self-report depression measure with strong psychometric properties with adolescents (Roberts et al. 1990). The CES-D was completed at screening, baseline, mid-intervention, post-intervention (after groups ended) and 6-month follow-up (after booster sessions were completed). Cronbach's alpha across administrations ranged from 0.86 to 0.89. At eligibility, post-intervention, and 6-month follow-up, youth completed the K-SADS-PL to assess for depression diagnoses. A detailed timeline was completed at the 6-month follow-up assessment to ensure an accurate determination of diagnoses occurring in the prior 6 months. As part of the K-SADS-PL, youth were assigned a score on the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), a clinician-rated scale of overall functioning, which ranges from 1 to 100 (Shaffer et al. 1983). The CGAS score is given based on functioning at home, school, and with peers; scores over 70 indicate minor impairments in functioning.

The evaluations were conducted by independent evaluators (IEs), who were graduate students in clinical or school psychology. The IEs were trained in the assessments and participated in a reliability study of 10 recorded assessments. Inter-rater reliability was derived through interclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) per Shrout and Fleiss (1979) through variance component models, assessing variability between the raters compared to the total variability. Reliability was 0.96 for depression diagnoses on the K-SADS-PL and 0.89 for the CGAS. Ten percent of completed evaluations were randomly selected and re-rated by a senior diagnostic interviewer with ICCs of 0.89 for diagnoses and 0.96 for the CGAS. IEs were blinded to intervention condition throughout the study. When the blind was broken, the case was reassigned to another evaluator. Each IE was asked to guess participants' intervention assignment after completing their final evaluations. The mean correct classification rate was 51.1 %, or chance level, providing good evidence that the blind was maintained.

Data Analytic Strategy

For the continuous measures of depression (CES-D) and global functioning (CGAS), we implemented a three-level hierarchical linear model (HLM) to examine the differences between the interventions on rates of change from baseline to the 6-month follow-up evaluation. We chose HLM due to its flexibility to accommodate the multiple levels of clustering in our data (repeated measurements per individual and multiple individuals within a common group), as well as to address the nature of individual change over time. The first level models individual scores over time. At the second level, the individual intercept and slope are outcomes dependent on group; the group-specific slopes are used as outcomes in the third level to contrast if the rate of change differs between IPT-AST and GC. This three-level HLM treats group as a random effect; school was treated as a fixed effect to allow the on average values of the outcome measures to vary between schools. In addition, we examined whether gender, age, family income, or minority status were significantly related to the intercept or slope of the main outcomes. Income was significantly related to the intercept and so was retained in both models as a co-variate. For the CES-D analyses, screening CES-D was also included as a covariate. HLM requires multivariate normality of the residuals. Assessment of the distribution of each outcome indicated that a square root transformation was needed for the CES-D to guarantee multivariate normality of the residuals. The CGAS required no transformation. HLM is flexible in handling missing data; subjects with missing values are retained in all analyses while missed assessments are not. Pattern-mixture models assessed whether intervention effect was dependent on missing data patterns (Hedeker and Gibbons 1997). These indicated no significant effects of missing data.

Effect sizes for HLM models (Cohen's d) were derived using the formula specified by Raudenbush and Liu (2001). Additionally, following the recommendation of Kraemer and Kupfer (2006). we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) as a measure of clinical significance (Walter 2001). The NNT estimate represents the expected number of additional adolescents who would need to receive IPT-AST as compared to GC to prevent non-response. A 50 % reduction on the CES-D and a 1.5 standard deviation improvement on the CGAS were defined as a response. An NNT of 2.3 is a large effect, 3.6 is a medium effect, and 8.9 is a small effect (Kraemer and Kupfer 2006). To examine intervention differences in time to depression diagnoses, we used Cox regression. All models were fit using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc 2011).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Baseline Differences

There were no significant differences between the conditions on any baseline clinical, diagnostic, or demographic variables. The majority of youth (77.42 %) reported no current DSM-IV diagnoses; 17 had a current depressive disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS), meaning they endorsed three or four threshold symptoms. Eight youth had a past diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia (five in IPT-AST, three in GC). As seen in Table 1, there was a significant decrease in CES-D scores between the screening and the baseline evaluation which occurred on average 7.37 weeks (SD=1.66) later. As such, screening CES-D scores was included as a covariate in the model that examined change in CES-D scores.

Attendance, Intervention Satisfaction, and Attrition

Three adolescents in each condition attended no group sessions; all of them attended at least one individual session. On average, IPT-AST youth attended 6.80 (SD=1.85) group sessions and GC youth attended 6.18 (SD=1.85) group sessions, t(183)= −2.28, p<0.05. IPT-AST youth attended significantly more pre-group (M=2.00 vs. M=0.90), mid-group (M=0.98 vs. M=0.63), and booster sessions (M=3.64 vs. M=2.78) than GC youth. In IPT-AST, 48.4 % of the mid-group sessions involved a parent; GC counselors did not include parents in mid-group sessions. Satisfaction with the intervention was high in both conditions. In IPT-AST, 58.7 % rated the intervention as very helpful and 29.3 % as helpful. In GC, 51.7 % rated the groups as very helpful and 39.3 % as helpful. Despite similar ratings of intervention satisfaction across the two conditions, significantly, more IPT-AST youth (83.5 %) than GC youth (67.0 %) reported feeling confident that they did not need additional services after completing the group, χ2=6.55, p<0.05.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, there was little attrition from the assessments. Less than 2 % of the participants did not provide data at post intervention, and 6 % did not provide data at 6-month follow-up. Only one participant did not complete any of the follow-up assessments.

Intervention Effects

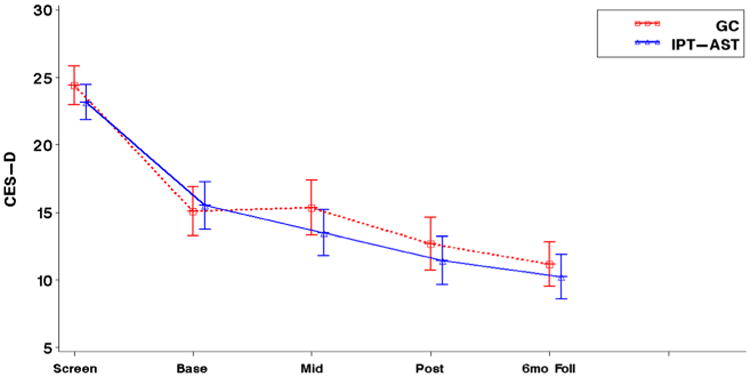

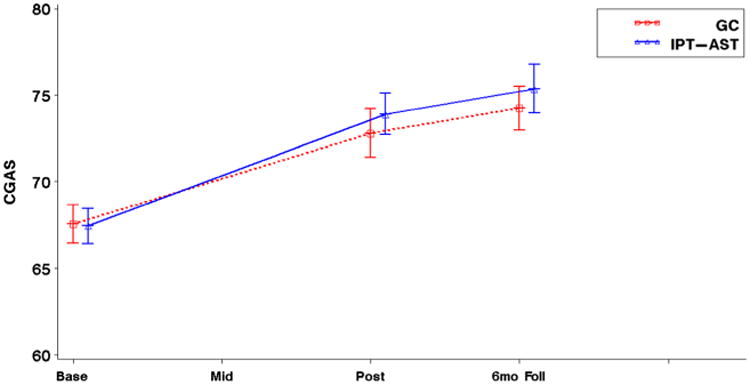

Goodness of fit tests indicated that a natural logarithmic transformation of time, which accommodates greater rate of change earlier in the intervention and smaller rate of subsequent change, fits the data significantly better than time in weeks. Table 2 lists the estimated means at each time point and the slopes for the two intervention conditions. Slopes reflect change in symptoms in log time. We report the total change from baseline to the 6-month follow-up to ease interpretation. As depicted in Fig. 2, there was a differential rate of change on the CES-D from baseline to the 6-month follow-up, t(181)=2.03, p=0.04, d=0.31, controlling for screening CES-D. IPT-AST youth decreased a total of 5.43 points, whereas GC youth decreased a total of 2.99 points. Using a definition of response of a 50 % reduction in CES-D scores from baseline, there was a 40.5 % response rate in IPT-AST and a 29.7 % response rate in GC (NNT=7.47), a small to medium effect. On the CGAS, there was a significant difference in slopes between the two intervention conditions, t(182)=-2.01, p<0.05, d= 0.31. The change in CGAS scores from baseline to the 6-month follow-up was 8.15 points for IPT-AST and 6.66 points for GC (see Fig. 3). Using a definition of response of a 1.5 SD improvement in CGAS scores, response rates were 44.9 % for IPT-AST and 32.9 % for GC (NNT=8.33), corresponding to a small to medium effect.

Table 2. Three-level HLM estimated means and slopes.

| Outcome | GC | IPT-AST | Slope estimates | p value | Cohen's d (95 % CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | GC (SE) | IPT-AST (SE) | |||

| CES-D | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 91 | 15.07 | 8.65 | 95 | 15.51 | 8.52 | −0.12 (0.03) | −0.22 (0.04) | 0.04 | 0.31 (0.02–0.60) |

| Mid | 90 | 12.97 | 9.64 | 94 | 11.72 | 8.25 | ||||

| Post | 90 | 12.62 | 9.28 | 93 | 11.12 | 8.57 | ||||

| 6-month | 85 | 11.77 | 7.59 | 89 | 9.68 | 7.82 | ||||

| CGAS | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 91 | 67.55 | 5.24 | 95 | 67.44 | 4.98 | 1.80 (0.14) | 2.20 (0.14) | 0.04 | 0.31 (0.02–0.60) |

| Post | 90 | 72.41 | 6.69 | 93 | 73.39 | 5.80 | ||||

| 6-month | 85 | 74.20 | 5.85 | 89 | 75.59 | 6.64 | ||||

Baseline means are observed values. Post-baseline, the means are model-based estimates within the three-level HLM adjusted for school, the correlation attributable to patients nested within groups, as well as baseline covariates as warranted. Slope estimates indicate change in outcome per log-week from baseline. Slope estimates for the CES-D are the change in the transformed outcome per log-week

Fig. 2. Mean profile plots for the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D).

Fig. 3. Mean profile plots for the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS).

Five adolescents in IPT-AST (5.3 %) and two in GC (2.2 %) received a diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia at either post-intervention or the 6-month follow-up. We used standard Cox regression to fit time to diagnosis, including school as a covariate similar to the continuous variables. A baseline diagnosis of DDNOS was a significant predictor of subsequent depression, so this was retained in the model; the demographic variables were not significant, so they were dropped from the final model. Cox models indicated that the differences in rates of onset of depression diagnoses across the two conditions was not significant, χ2=1.64, p=0.20.

Discussion

The first aim of the study was to examine whether IPT-AST would have a greater impact on depressive symptoms and overall functioning than counselor-led groups matched on frequency and duration of sessions. Although both conditions demonstrated significant improvements from baseline to the 6-month follow-up, results indicated that IPT-AST produced significantly greater improvements in self-reported depressive symptoms and evaluator-rated overall functioning than GC. The effect size for change in depressive symptoms and the NNT are in the small to medium range, reflecting that the differences between the two conditions were modest. Though the effect size is smaller than our initial IPT-AST studies, it is similar to or larger than those reported in meta-analyses of depression prevention studies (Merry et al. 2011; Stice et al. 2009). Importantly, our study included an active control condition, whereas the majority of studies in these meta-analyses did not. Merry et al. (2011) examined the few studies with an active control condition and found no evidence of significant effects on depressive symptoms or diagnoses in these studies. Within individual trials, Stice et al. (2008) found effect sizes of 0.29 at post-intervention and 0.05 at 6-month follow-up in their pairwise contrasts of their CB program and a supportive expressive group. Gillham et al. (2007) found that the Penn Resiliency Program (PRP) was significantly more effective than an alternative non-cognitive-behavioral intervention at post-intervention in two schools (d=0.18), but these findings were not replicated at a third school and did not persist at the 6-month follow-up.

Our findings of significant differences in rates of change between IPT-AST and GC in self-reported depressive symptoms provide important evidence of specificity of effects. This is particularly encouraging given that school counselors reported using a number of evidence-based approaches, particularly cognitive techniques, and GC sessions were longer and more frequent than group sessions typically delivered in these schools. In addition, many of the adolescents in the study would not have been identified as having elevated depression without the screening and so are unlikely to have received services in the school outside of the project. Thus, GC was an ecologically valid and rigorous control condition. In fact, several of the GC groups were cognitive-behavioral and likely addressed other key risk factors for depression such as negative cognitions, problems in coping, and ineffective problem-solving (Garber 2006). This may explain the modest differences found between IPT-AST and GC. Of note, none of the demographic variables we examined moderated intervention outcomes, despite adequate power to detect moderation effects. This suggests that the benefits of IPT-AST are robust across gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income.

We also found significant intervention effects (d=0.31) on overall functioning. Adolescents in both conditions showed significant improvements in functioning from pre-intervention to the 6-month follow-up, yet IPT-AST youth showed significantly greater improvements, with an NNT of 8.33. To date, only a handful of depression prevention studies have examined effects on functioning (e.g., McCarty et al. 2013; Stice et al. 2008; Young et al. 2006, 2010). despite a call to examine functional outcomes as well as symptoms in intervention studies (Kazdin 2002). The impact on overall functioning, as rated by blind independent evaluators, is important given that youth with subthreshold depression experience considerable psychosocial impairments (Lewinsohn et al. 2000). None of the demographic variables moderated rates of change in overall functioning. These findings and those from prior IPT-AST studies indicate that IPT-AST improves functioning for youth from diverse demographic backgrounds.

On the other hand, IPT-AST did not reduce risk for onset of depression diagnoses relative to GC. This is disappointing since the main goal of prevention is to reduce the occurrence of new cases. Within the depression prevention literature, some studies have found an impact on rates of depression diagnoses and others have not (Merry et al. 2011). Our findings are similar to Stice et al. (2008). who found that the CB program did not reduce risk for major depression relative to supportive expressive groups or bibliotherapy in the 6-month follow-up. All three interventions significantly reduced major depression compared to the assessment-only control. Unfortunately, our study did not include an assessment-only control group, so we do not know whether the rates of depression diagnoses in IPT-AST and GC were lower than would have naturally occurred in this high risk sample. Using similar eligibility criteria, Stice et al. (2008) found that 6.8 % of the CB condition and 13.1 % of the assessment-only condition had a depression diagnosis in the 6-month follow-up. The fact that rates of diagnoses in our sample are lower than previously reported in no intervention control groups and similar to those reported in CB conditions suggests a possible preventive effect of IPT-AST and GC on depression diagnoses, though this is speculative. The lack of differences between IPT-AST and GC may be explained by the frequent use of cognitive techniques in GC or shared non-specific factors of these interventions (e.g., getting feedback from peers). An important test of the merits of IPT-AST, relative to GC, will be to determine whether differences in rates of diagnoses emerge over time. In the long-term follow-up, it will also be informative to examine whether rates of depression diagnoses within the GC condition differ as a function of the intervention techniques utilized in the groups.

People have questioned the feasibility of implementing indicated depression prevention programs given concerns about identifying appropriate youth, low levels of interest, poor attendance, and small effects. Our experiences from this study shed light on a number of these issues. A third of families consented and assented to the depression screening, with considerable variability across schools. We had the greatest response rates when we sent consent forms at home as part of the summer mailing from schools, and when we were present at back to school nights with consent forms for parents to sign. For indicated prevention efforts to be fruitful, more work needs to be done to determine the best ways to identify appropriate youth and to educate parents about the benefits of conducting screenings in schools. Regarding interest in the prevention groups, half of the adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms agreed to participate in the prevention study. This is better than some earlier studies (e.g., Clarke et al. 1995; Young et al. 2006). but suggests a need to improve mental health literacy in schools to reduce stigma and increase engagement in these programs. This might include educating the school community about the effects of these programs, the benefits of preventing difficulties before they become more significant, and the importance of psychological well-being for a variety of outcomes. Relatedly, a number of studies have found poor attendance to prevention programs (e.g., Gillham et al. 2007; Stice et al. 2008). We have not found the same to be true in our IPT-AST studies. In the current study, the average IPT-AST participant attended 89.5 % of the group and individual sessions, considerably higher than rates reported elsewhere in the literature. The high attendance may be linked to adolescents' experience that the groups were helpful and that the focus on relationships was pertinent to their lives. This suggests that it is feasible to get youth to attend depression prevention groups once they agree to participate, but we need to continue to work to make these programs engaging and relevant.

Limitations of this study should be noted. The first limitation of this study, and other indicated prevention studies, is that only half of adolescents with elevated CES-D scores agreed to participate in the eligibility evaluation and prevention study. Although there were no significant differences between youth who enrolled in the study and those who refused, the high refusal rate limits our ability to generalize these findings. A second limitation relates to the choice of GC as a control group. We chose GC because it approximates the variety of groups that can be delivered in schools without additional training or supervision in a specific intervention manual, while being enhanced to match IPT-AST on frequency and duration of sessions. This allowed us to examine whether IPT-AST offers benefits above and beyond other types of groups conducted in schools. Although the variability in content across GC groups may limit study conclusions, the effect attributable to group differences was non-significant for both HLM models. Heterogeneity of groups accounted for only a small amount of the total variance in change in symptoms and functioning over time. Relatedly, despite significant efforts to make GC an equivalent control group, there were differential rates of attendance for IPT-AST and GC. It is possible that the greater effects of IPT-AST on symptoms and functioning are attributable to greater intervention hours. However, we believe that the excellent attendance to IPT-AST speaks to its appeal as a preventive intervention. Another difference is that GC leaders had significantly more years of counseling experience than IPT-AST leaders. Of note, years of experience did not predict or moderate intervention outcomes. Finally, all of the IPT-AST groups had two leaders, whereas most GC groups had one leader. This difference may have impacted study outcomes.

An additional limitation is that, for budgetary and sample size reasons, we did not include an assessment-only control group. We found a large decline in CES-D scores from the screening to the baseline evaluation before any intervention was delivered, as has been found in other prevention studies (McCarty et al. 2013; Wijnhoven et al. 2014). These reductions suggest that the consent process and diagnostic evaluations may be powerful psychoeducational interventions that begin the process of symptom improvement. Most prior prevention studies have not reassessed depression symptoms immediately before the prevention program. This may have resulted in an overestimation of intervention effects, as pre-intervention declines in symptoms were included in effect estimates. Future studies should include two pre-intervention assessments and an assessment-only control group to rule out spontaneous improvements or regression to the mean (Arrindell 2001). This will strengthen the conclusions that can be made about the effects of these programs. Lastly, the follow-up time period reported in this paper is relatively short. The true test of a prevention program is its efficacy over a greater period of time. We are collecting follow-up data through 2-year post-intervention and plan to examine the long-term effects of IPT-AST and GC on depressive symptoms, depression diagnoses, overall functioning, and other important and ecologically relevant outcomes.

In conclusion, initial results from this indicated prevention trial suggest that IPT-AST produces significant reductions in depressive symptoms and improvements in overall functioning relative to GC, an active control group, in a sample of diverse youth with elevated depressive symptoms. However, there was no evidence of specific effects of IPT-AST on rates of depression diagnoses in 6 months following the intervention. Thus, the short-term effects of IPT-AST, relative to GC, were modest. This is likely in part due to the use of an active control condition, as well as the fact that IPT-AST only targets one class of risk factors for depression, specifically interpersonal vulnerabilities. Preventive interventions may need to address multiple risk and protective factors for depression to increase effects (Garber 2006). Future research will examine potential moderators of intervention outcome, mediators of intervention effects, and the long-term impact of these prevention programs on depressive symptoms, overall functioning, and depression diagnoses, as well as other outcomes such as social functioning, school functioning, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. If significant differences between IPT-AST and GC persist over time and across outcomes, efforts should be made to identify at-risk youth who would benefit from prevention efforts, increase engagement in these prevention programs, and determine whether school personnel can be trained to effectively deliver IPT-AST. Future research will need to examine the costs of training school counselors to implement IPT-AST and other evidence-based depression prevention programs and determine whether the benefits of these programs justify the additional costs of implementation.

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was funded by an NIMH grant (R01MH087481).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Ethical Approval This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rutgers University.

Informed Consent Parents gave informed consent for their own participation and the participation of their children; adolescents assented to the project.

References

- Allen JP, Insabella G, Porter MR, Smith FD, Land D, Phillips N. A social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:55–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell WA. Changes in waiting-list patients over time: Data on some commonly-used measures. Beware! Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1227–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Wanner B, Morin AJS, Vitaro F. Relations with parents and with peers, temperament, and trajectories of depressed mood during early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:579–594. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm D, Sanderson K, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Saxena S. Reducing the global burden of depression: Population-level analysis of intervention cost-effectiveness in 14 world regions. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184:393–403. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Smit F, Mihalopoulos C, Beekman A. Preventing the onset of depression disorders: A meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1272–1280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood J, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Rollefson M, Doksum T, Noonan D, Robinson G, Teich J. DHHS Pub No (SMA) 05–4068. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. School mental health services in the United States, 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J. Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:S104–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Freres DR, Chaplin TM, Shatté AJ, Samuels B, Seligman ME. School-based prevention of depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and specificity of the Penn Resiliency Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:9–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. The state of child and adolescent psychotherapy research. Child and Adolescent Mental Heath. 2002;7:53–59. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Solomon A, Seeley JR, Zeiss A. Clinical implications of “subthreshold” depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masia-Warner C, Nangle DW, Hansen DJ. Bringing evidence-based child mental health services to the schools: General issues and specific populations. Education and Treatment of Children. 2006;29:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Violette HD, Duong MT, Cruz RA, McCauley E. A randomized trial of the positive thoughts and action program for depression among early adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:554–563. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.782817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry SN, Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Brudevold-Iverson T, Bir JJ, McDowell H. Psychological and educational interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal. 2011;7:1409–1685. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Liu XF. Effects of study duration, frequency of observations, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. Assessment of depression in adolescents using the center for epidemiological studies depression scale. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Child and adolescent depression: Causes, treatment and prevention. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:276–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9.3 user's guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescents' relationships with their mothers and fathers: Associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:144–154. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;2:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents outperforms two alternative interventions: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: Factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Gau JM, Wade E. Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: Effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:856–867. doi: 10.1037/a0020544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter SD. Number needed to treat (NNT): Estimation of a measure of clinic benefit. Statistics in Medicine. 2001;20:3947–3962. doi: 10.1002/sim.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR, Donenberg GR. Development of the therapy procedures checklist: A therapist-report measure of technique use in child and adolescent treatment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:168–180. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven LA, Creemers DH, Vermulst AA, Scholte RH, Engels RC. Randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a depression prevention program (‘Op Volle Kracht’) among adolescent girls with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9773-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L. IPT-AST supervision checklist. Unpublished measure 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L. Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST): Manual for the depression prevention initiative study. Unpublished manual 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training: An indicated preventive intervention for depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1254–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L, Gallop R. Preventing depression: A randomized trial of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:426–433. doi: 10.1002/da.20664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]