Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biogenesis in Gram-negative organisms involves its biosynthesis in the cytoplasm and subsequent transport across three cellular compartments to the cell surface. We developed a fluorescent probe that allows us to determine the spatial distribution of LPS in whole cells. We show that polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN) containing a dansyl fluorophore specifically binds to LPS in membranes. We show that this probe detects decreases in LPS levels on the cell surface when LPS biosynthesis is inhibited at an early step. We also can detect accumulation of LPS in particular subcellular locations when LPS assembly is blocked during transport, allowing us to differentiate inhibitors targeting early and late stages of LPS biogenesis.

The discovery of new antibiotics to treat Gram-negative infections is a major unmet clinical need. It is more difficult to treat Gram-negative infections than to treat Gram-positive infections because of differences in cellular physiology. The cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria consists of inner and outer membranes with a thin layer of cell wall in between the two membranes. The outer membrane is an asymmetric bilayer. The outer leaflet is made up of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), while the inner leaflet is made up of phospholipids (Figure 1a).1,2 The assembly of LPS on the cell surface forms a permeability barrier to many small hydrophobic molecules.3 Disruption of LPS biogenesis makes Gram-negative organisms hypersusceptible to a broad range of antibiotics they generally tolerate.

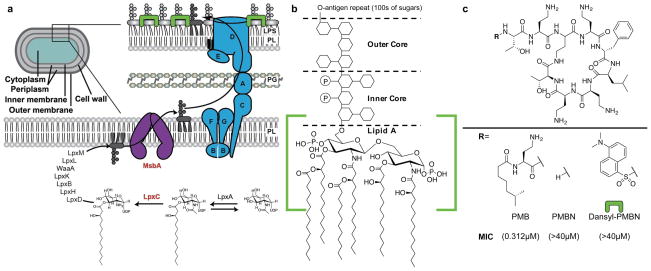

Figure 1.

Direct detection of LPS at the cell surface using a fluorescent polymyxin derivative. (a) The pathway for LPS biosynthesis and transport. A subset of the genes involved in biogenesis are shown for simplicity. Schematic showing the cellular compartments of a Gram-negative organism and an enlargement showing cell envelope containing the phospholipid (PL) bilayer, the peptidoglycan (PG) cell wall and asymmetric outer membrane containing LPS. The inner membrane flippase MsbA (shown in purple) and the seven essential lipopolysaccharide transport proteins (LptA-G; shown in blue) are responsible for transport to the cell surface. An LPS-specific fluorescent probe is shown in green. Proteins targeted in this study are shown in red. (b) A canonical structure of LPS. The Lipid A core as found in E. coli contains six fatty acyl chains attached to a disaccharide bisphosphate. Details of the inner and outer core as well as the O-antigen are omitted for simplicity. The polymyxin B (PMB) binding site on LPS is designated by the green brackets. (c) The structure of PMB as well as the de-lipidated peptide polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), and the fluorescent probe Dansyl-PMBN. Removal of the lipid tail dramatically decreases antimicrobial activity. MIC values are measured against A. baumannii ATCC 19606.

The biogenesis of LPS is a complicated pathway involving more than one hundred genes. Biosynthesis of LPS is initiated by the Lpx pathway in the cytoplasm and then, after synthesis has been completed at the inner membrane, it is transported to the outer membrane by the lipopolysaccharide transport (Lpt) pathway (Figure 1a).4,5 LPS is essential in most Gram-negative organisms, including the model organism Escherichia coli, while some, such as Acinetobacter baumannii, can survive without LPS.6,7 LPS is composed of a disaccharide bisphosphate appended with multiple fatty acyl chains and in pathogenic strains is further elaborated with hundreds of sugars comprising the O-antigen (Figure 1b). The lipid A portion ordinarily interacts with divalent metal cations producing a highly organized polyelectrolyte structure that prevents facile penetration of hydrophobic molecules.4

We are interested in understanding how LPS assembly occurs and have identified intermediate transport steps both in living cells and in vitro.8 We wondered whether we could develop a fluorescent probe to directly visualize accumulation of LPS at different steps in the pathway. The development of such an assay first required a compound which specifically recognizes LPS but would minimally perturb cells. Polymyxin B (PMB) is a member of the polymyxin family of antibiotics, which are polycationic lipopeptides clinically used as a drug of last resort in the treatment of Gram-negative infections.9 PMB consists of a heptapeptide macrocycle and a tripeptide chain capped by a fatty acid (Figure 1c). PMB binds to LPS through interaction of its positively-charged 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (Dab) residues with the negatively-charged phosphates on lipid A (Figure 1b; green bracket), which disrupts the packing of metal cations with the lipid A phosphate groups. The acyl chain is proposed to insert into the membrane causing defects that give rise to its antimicrobial activity. PMB nonapeptide (PMBN), consisting of only the macrocycle and a dipeptide chain, is not antimicrobial but still binds to LPS (Figure 1c). We wanted a fluorescent probe that would minimally perturb cells, so PMBN seemed like an ideal choice.

Numerous fluorescent derivatives of polymyxin have been prepared. Comprehensive studies have been performed in part to characterize the requirements for polymyxin binding to LPS and to improve the therapeutic potential of this important class of antibiotics.10–18 We selected one, a dansylated version of PMBN, to synthe-size.12 The dansyl fluorophore was ideal for our purposes because the extinction coefficient of dansyl groups increases significantly in hydrophobic environments, such as the cell membrane, which increases signal-to-noise without requiring extensive sample washing. Dansyl-PMBN was synthesized by adapting established solid phase methods for the synthesis of polymyxin derivatives. (Figure 1c, Scheme S1).12,19

We first measured the probe’s antimicrobial activity. Dansyl-PMBN displays less antimicrobial activity against the Gram-negative pathogen A. baumannii (Figure 1c, Table S1), but retains more activity against E. coli, presumably because the dansyl group is relatively hydrophobic like the lipid tail in the parent compound (Table S1). The Gram-positive organism Bacillus subtilis does not contain LPS and accordingly the Dansyl-PMBN and parent drug have similar minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC; Table S1). We concluded that Dansyl-PMBN would be an ideal compound with which to study LPS levels and distribution in A. baumannii.

We sought to confirm that the dansylated polymyxin derivative would yield an LPS-dependent fluorescence. To determine whether Dansyl-PMBN could discriminate between cell surfaces containing LPS (Gram-negative) and those without LPS (Gram-positive), we treated both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria with Dansyl-PMBN. The treatment concentration was chosen based on the concentration that yielded optimal signal-to-noise during imaging. For both A. baumannii and B. subtilis, this treatment concentration was below the MIC for Dansyl-PMBN (Table S1). We found that Dansyl-PMBN stained a Gram-negative organism (Figure 2a, top row), while it did not stain a Gram-positive organism (Figure 2a, bottom row). Although E. coli was treated with concentrations of Dansyl-PMBN greater than the MIC, the relative staining between A. baumannii and E. coli were similar (Figure 2a, top and middle rows). This led us to conclude that Dansyl-PMBN could discriminate between Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, even at concentrations greater than the MIC.

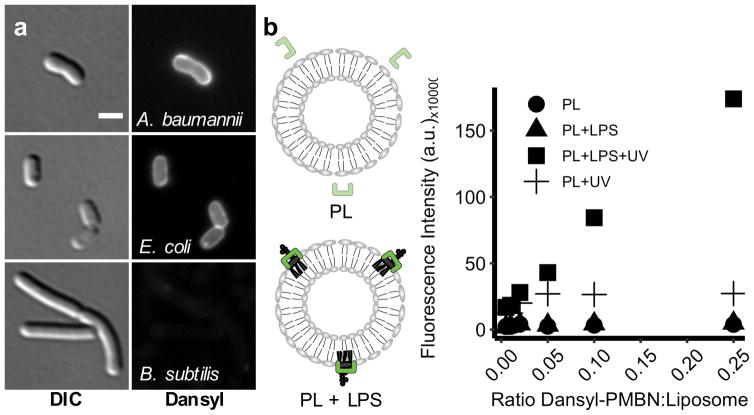

Figure 2.

A dansylated polymyxin derivative binds LPS on bacterial cell surfaces. (a) Dansyl-PMBN selectively stains Gram-negative organisms. A. baumannii, E. coli, and B. subtilis were incubated with Dansyl-PMBN (12 μM) at room temperature for 30 minutes before being imaged. DIC: Differential interference contrast. Scale bar: 2 μm. (b) Dansyl-PMBN specifically recognizes LPS in liposomes. Phospholipid (PL) liposomes with or without LPS were prepared and incubated with a constant amount of Dansyl-PMBN (1.8 μM). Samples were read on a fluorescent plate reader using Ex/Em=340/520nm (+UV) or without Ex.

We wondered whether the fluorescence observed in cells is dependent on LPS or simply an association with the cell membrane due to other differences between Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms. We prepared liposomes with and without LPS from E. coli-extracted polar lipids using a detergent dilution method (Figure S4). Fluorescence increased significantly when LPS was included in the liposome preparation (Figure 2b). If selective for LPS, Dansyl-PMBN should exhibit higher fluorescence when exposed to a lipid membrane containing LPS but fluoresce poorly in the presence of a phospholipid membrane. Further characterization of the fluorescence properties of Dansyl-PMBN demonstrated a long linear range (Figure S5) and an LPS-dependent response to LPS in solution (Figure S6).20 Mg2+ competes with polymyxins for the phosphates on Lipid A while EDTA chelates Mg2+ and can be used to reverse inhibition of polymyxin binding by Mg2+.16 We found that Dansyl-PMBN gave similar results (Figure S7). Our results indicated that Dansyl-PMBN was primarily associating with the membrane only when LPS was present. We therefore concluded that Dansyl-PMBN exhibited LPS-dependent fluorescence both in vivo and in vitro.

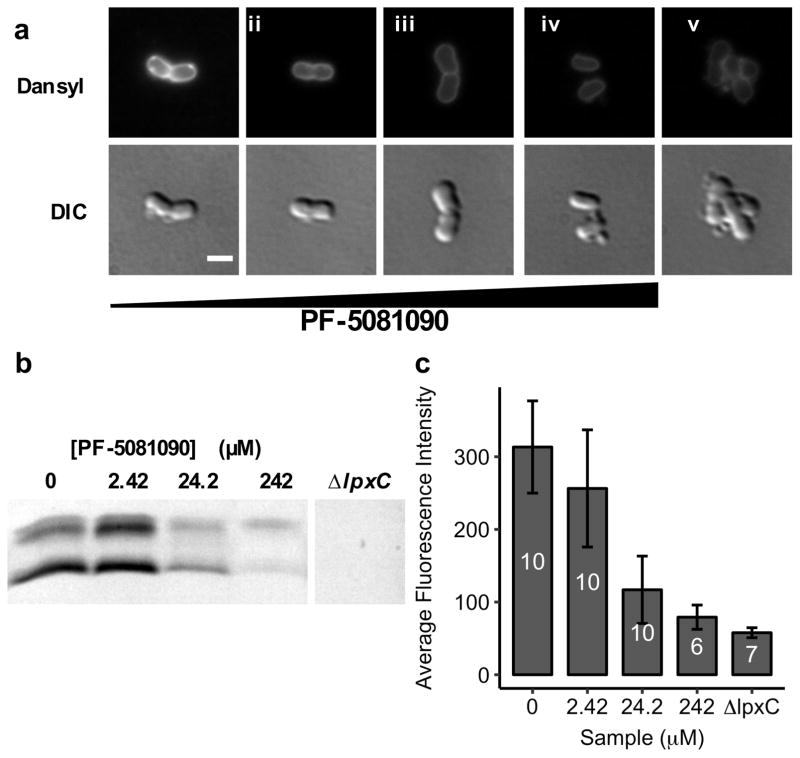

We wondered whether Dansyl-PMBN was sensitive enough to discriminate LPS levels in vivo. The first committed step in LPS biosynthesis is catalyzed by the enzyme LpxC.4,6 This enzyme deacetylates N-acetyl glucosamine and, because its removal results in the complete loss of LPS from cells, it has been an important target for drug development. PF-5081090 is a potent LpxC inhibitor.21 Although it kills E. coli at sub-micromolar concentrations (MIC=0.08μM), it is much less potent against A. baumannii (MIC=620μM) because LPS is non-essential in A. baumannii.22 Using A. baumannii allowed us to compare drug treatment with genetic knockouts. We generated an lpxC-null mutant in A. baumannii ATCC 19606. We treated A. baumannii 19606 with increasing concentrations of PF-5081090 and compared it to untreated A. baumannii 19606 and ΔlpxC (Figure 3a, c). We found that fluorescence decreased with increasing concentrations of PF-5081090. This correlated with decreasing levels of LPS as measured by silver stain SDS-PAGE (Figures 3b, S8).23 Dansyl-PMBN was therefore sufficiently sensitive to discriminate changes in cellular levels of LPS.

Figure 3.

Dansyl-PMBN can detect decreasing levels of LPS on the cell surface when biosynthesis is inhibited. (a) A. baumannii with increasing concentrations of PF-5081090. (i) 0 μM (ii) 2.42 μM (iii) 24.2 μM or (iv) 242 μM PF-5081090 and (v) ΔlpxC. Scale bar: 2 μm. (b) SDS-PAGE gel with LPS levels as determined by silver stain. Samples were normalized by OD, and only the low molecular weight LPS core region is shown for clarity. (c) Average cellular fluorescence intensity decreases with increasing concentrations of PF-5081090. Numbers inside bars correspond to number of cells analyzed per sample. Error bars are standard deviation.

Having shown that depletion or removal of LPS could be monitored in A. baumannii, we wondered whether we could apply the same approach in organisms where LPS is essential. We monitored fluorescence intensity in E. coli cells treated with varying amounts of PF-5081090. Cells treated with 0.1-, 1-, and 10× MIC showed characteristic depletion that matched the amount of LPS present as determined by LPS silver stain (Figure S9). Importantly, the fluorescence phenotype matched that found in A. baumannii, despite the fact that E. coli were treated with a lethal concentration of Dansyl-PMBN. We concluded that LPS levels could be monitored even in organisms in which LPS is essential.

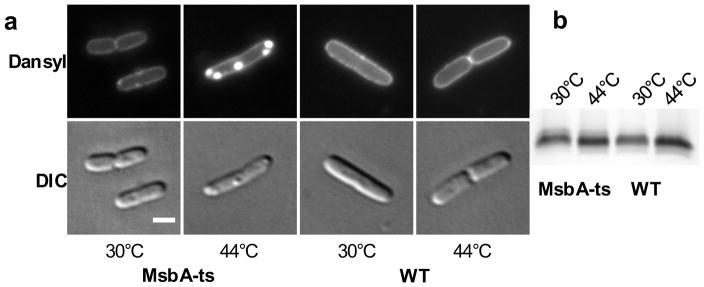

PF-5081090 blocks LPS biosynthesis early in the pathway and accumulates simple sugars that do not contain the Lipid A components required for PMB recognition, which results in decreased Dansyl-PMBN fluorescence. We wondered whether we would able to detect LPS accumulation inside the cell after biosynthesis of the Lipid A core has been completed but LPS has not yet been transported to the cell surface. A temperature-sensitive mutant of E. coli has previously been reported, in which MsbA, the flippase responsible for flipping LPS from the inner leaf-let of the inner membrane to the outer leaflet of the inner membrane can be inactivated (Figure 1a).24 We grew the temperature-sensitive mutant (MsbA-ts) at the permissive temperature (30°C) and then shifted to the non-permissive temperature (44°C) for 40 minutes. While LpxC inhibition resulted in reduced fluorescence, heat inactivation of MsbA produced intense fluorescence in the interior of the cell instead of staining the cell surface (Figures 4, S10). Importantly, the amount of LPS observed in cells grown under permissive or non-permissive temperatures is comparable as judged by silver stain. We conclude that the change of fluorescence localization reflects accumulation of LPS at the step inhibited. Fluorescence punctae correspond to dense regions in the DIC images, which are expected to be inner membrane ruffles that were observed in transmission electron micrographs obtained by Raetz and colleagues.24 Apparently, this membrane material contains high local concentrations of LPS.

Figure 4.

Fluorescent signatures can be used to determine cellular targets. (a) E. coli MsbA-ts and the WT strain were grown at 30°C for 2 hours and shifted to 44°C to inactivate MsbA for 40 minutes. Samples were stained with Dansyl-PMBN (6 μM). Scale bar: 2 μm. (b) SDS-PAGE gel with LPS levels as determined by silver stain. Samples were normalized by OD, and only the low molecular weight LPS core region is shown for clarity.

In conclusion, we have developed a fluorescent probe that enables us to visualize localization of LPS in cells. Importantly, this tool provides characteristic fluorescence signatures when LPS transport has been blocked during translocation across the inner membrane. It remains to be seen whether inhibition later in the transport pathway, in Lpt components, show a distinct phenotype. Dansyl-PMBN provides a simple method that could be used as a secondary screen to study compounds of unknown mechanism to see whether, and at what stage, they inhibit LPS biogenesis. In principle, such analysis could be adapted to a high-content screen for finding inhibitors of LPS biogenesis because the accumulation observed is a unique phenotype.

METHODS

Fluorescence labeling of bacteria using Dansyl-PMBN

Cells were seeded at a density of 106 cell/mL, cultured for 2 hours in LB liquid medium at 37°C (220 rpm) and incubated for 30 minutes with Dansyl-PBMN at a final concentration of 12 μM. The cells were then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (dansyl channel, λex= 405/15 nm, λem=535/50 nm).

Inhibition of labeling by LpxC inhibitor PF-5081090

Cells were cultured and stained with Dansyl-PMBN as above except that PF-5081090 was added to final concentrations of 0, 2.42, 24.2, or 242 μM (A. baumannii 19606) or 0, 0.008, 0.08, or 0.8 μM (E. coli NR754).

Inactivation of MsbA in E. coli WD2

Cells were cultured as above except that cells were initially cultured at 30°C for 2 hours. Cultures were shifted to 44°C for 40 minutes to inactivate MsbA. Samples were then labeled with Dansyl-PMBN at a final concentration of 6 μM.

Silver staining analysis of LPS and whole cell lysates

Samples from PF-5081090 treated samples (800 μL) were normalized by OD600 measurements and then pelleted by centrifugation (5 minutes, 4,000 rpm) at room temperature. The supernatant was carefully removed and 20 μL Laemmli Sample Buffer (BioRad) was added. Samples were heated at 100 °C for 10 minutes to lyse cells. Samples were then normalized with sample buffer to correct for residual supernatant. For whole cell lysate silver staining, 5 μL of lysed sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (4–20% gradient gel, 150 V, 1 hour). Following electrophoresis, the gel was silver stained using the cell lysate method (for further information see SI). For LPS silver staining, remaining sample was digested by the addition of 10 μL Proteinase K solution (Qiagen) and incubated at 55°C for 1 hour. After digestion, 15 μL of sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% gel, 150 V, 1 hour). Following electrophoresis, the gel was silver stained using the LPS method (for further information, see SI).

Liposome preparation and characterization

The preparation of liposomes was adapted from literature with slight modification.25 E. coli polar lipid extract (30 mg/ml) was sonicated for 20–30 minutes and aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. To prepare the liposomes containing LPS, 3.6 mg of previously prepared polar lipid extract, n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG; 20% stock solution), 200 μg Ra-LPS, TBS (pH=8.0, 25× stock) were sequentially added to Milli-Q water to make a mixture of 400 μL in TBS (pH=8.0) containing 1.25% OG and incubated for 20 minutes. The mixture was divided into 100 μL aliquots, added to chilled 70.1 Ti ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman), and diluted with 9.6 mL of ice-cold TBS. After incubation on ice for 25 minutes, the suspensions were ultracentrifuged (2 hours, 64,000 rpm). The supernatant was aspirated, and the pellets in each tube were resuspended in 200 μL cold TBS (pH=8.0) containing 10% glycerol. The samples were then gently sonicated and aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For preparation of liposomes not containing LPS, Ra-LPS was substituted with an equal volume of Milli-Q water during liposome preparation.

Liposome binding assay with Dansyl-PMBN

To test Dansyl-PMBN binding with artificial vesicles, 0.3 μL of 1.2 mM Dansyl-PMBN stock solution was added to varying liposome concentrations (with or without LPS) as indicated, and diluted to a final volume of 20 μL (1.8 μM final concentration). Fluorescence was measured on a 96-well plate reader. The background fluorescence of liposomes was also measured as a negative control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19AI109764 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and R01GM066174 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Micro-scope images were obtained at the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School.

Footnotes

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Supplemental figures and detailed materials and methods can be found in the Supporting Information file (PDF).

Funding Sources

No competing financial interests have been declared.

References

- 1.Mühlradt PF, Golecki JR. Asymmetrical distribution and artifactual reorientation of lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane bilayer of Salmonella typhimurium. Eur J Biochem. 1975;51:343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamio Y, Nikaido H. Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: accessibility of phospholipid head groups to phospholipase c and cyanogen bromide activated dextran in the external medium. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2561–2570. doi: 10.1021/bi00657a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuda S, Sherman DJ, Silhavy TJ, Ruiz N, Kahne D. Lipopolysaccharide transport and assembly at the outer membrane: the PEZ model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:337–345. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JDF, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, Henry R, Crane B, St Michael F, Cox AD, Adler B, Nation RL, Li J, Boyce JD. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4971–4977. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00834-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steeghs L, den Hartog R, Boer den A, Zomer B, Roholl P, van der Ley P. Meningitis bacterium is viable without endotoxin. Nature. 1998;392:449–450. doi: 10.1038/33046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuda S, Freinkman E, Kahne D. Cytoplasmic ATP hydrolysis powers transport of lipopolysaccharide across the periplasm in E. coli. Science. 2012;338:1214–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1228984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storm DR, Rosenthal KS, Swanson PE. Polymyxin and related peptide antibiotics. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:723–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton BA. A Fluorescent Derivative of Polymyxin - Its Preparation and Use in Studying the Site of Action of the Antibiotic. J Gen Microbiol. 1955;12:226–236. doi: 10.1099/00221287-12-2-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soon RL, Velkov T, Chiu F, Thompson PE, Kancharla R, Roberts K, Larson I, Nation RL, Li J. Analytical Bio-chemistry. Anal Biochem. 2011;409:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsubery H, Ofek I, Cohen S, Fridkin M. Structure–Function Studies of Polymyxin B Nonapeptide: Implications to Sensitization of Gram-Negative Bacteria. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3085–3092. doi: 10.1021/jm0000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsubery H, Ofek I, Cohen S, Fridkin M. N-terminal modifications of Polymyxin B nonapeptide and their effect on antibacterial activity. Peptides. 2001;22:1675–1681. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsubery H, Ofek I, Cohen S, Eisenstein M, Fridkin M. Modulation of the hydrophobic domain of polymyxin B nonapeptide: Effect on outer-membrane permeabilization and lipopolysaccharide neutralization. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1036–1042. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL, Wang J, Thompson PE, Li J. Teaching ‘Old’ Polymyxins New Tricks: New-Generation Lipopeptides Targeting Gram-Negative ‘Superbugs’. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1172–1177. doi: 10.1021/cb500080r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore RA, Bates NC, Hancock RE. Interaction of polycationic antibiotics with Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccha-ride and lipid A studied by using dansyl-polymyxin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:496–500. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.3.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schindler PR, Teuber M. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes: morphological changes in the cytoplasm and in the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975;8:95–104. doi: 10.1128/aac.8.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deris ZZ, Swarbrick JD, Roberts KD, Azad MAK, Akter J, Horne AS, Nation RL, Rogers KL, Thompson PE, Velkov T, Li J. Probing the Penetration of Antimicrobial Polymyxin Lipopeptides into Gram-Negative Bacteria. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:750–760. doi: 10.1021/bc500094d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dansyl-PMBN was characterized by 1H and 13C NMR and its exact mass was measured (Figures S1–S3).

- 20.Liposome controls confirmed that Dansyl-PMBN does not disturb the membrane (Table S2).

- 21.Montgomery JI, Brown MF, Reilly U, Price LM, Abramite JA, Arcari J, Barham R, Che Y, Chen JM, Chung SW, Collantes EM, Desbonnet C, Doroski M, Doty J, Engtrakul JJ, Harris TM, Huband M, Knafels JD, Leach KL, Liu S, Marfat A, McAllister L, McElroy E, Menard CA, Mitton-Fry M, Mullins L, Noe MC, O’Donnell J, Oliver R, Penzien J, Plummer M, Shanmugasundaram V, Thoma C, Tomaras AP, Uccello DP, Vaz A, Wishka DG. Pyridone Methylsulfone Hydroxamate LpxC Inhibitors for the Treatment of Serious Gram-Negative Infections. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1662–1670. doi: 10.1021/jm2014875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The MIC against A. baumannii is likely due to off-target effects because LpxC can be genetically removed without lethal consequences.

- 23.There were low levels of fluorescence with A. baumannii ΔlpxC (Figure 3a(v)), This low-level fluorescence with A. baumannii ΔlpxC likely results from non-specific binding of Dansyl-PMBN to membranes (Figure 2b).

- 24.Doerrler WT, Reedy MC, Raetz CR. An Escherichia coli mutant defective in lipid export. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11461–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brundage L, Hendrick JP, Schiebel E, Driessen AJ, Wickner W. The purified E. coli integral membrane protein SecY/E is sufficient for reconstitution of SecA-dependent precursor protein translocation. Cell. 1990;62:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90111-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.