Abstract

Objective

Hemodynamics has been associated with aortic valve (AV) inflammation, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Here we tested the hypothesis that altered shear stress conditions stimulate the expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules in AV leaflets via a bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-and transforming growth fact (TGF)-β1-dependent pathway.

Methods and Results

The ventricularis or aortic surface of porcine AV leaflets were exposed for 48 hours to unidirectional pulsatile and bidirectional oscillatory shear stresses ex vivo. Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect expressions of the 4 inflammatory markers VCAM-1, ICAM-1, BMP-4, and TGF-β1. Exposure of the aortic surface to pulsatile shear stress (altered hemodynamics), but not oscillatory shear stress, increased expression of the inflammatory markers. In contrast, neither pulsatile nor oscillatory shear stress affected expression of the inflammatory markers on the ventricularis surface. The shear stress—dependent expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and BMP-4, but not TGF-β1, was significantly reduced by the BMP inhibitor noggin, whereas the TGF-β1 inhibitor SB431542 blocked BMP-4 expression on the aortic surface exposed to pulsatile shear stress.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that altered hemodynamics stimulates the expression of AV leaflet endothelial adhesion molecules in a TGF-β1-and BMP-4—dependent manner, providing some potential directions for future drug-based therapies for AV diseases.

Keywords: heart valves, calcification, shear stress, signal transduction

The aortic valve (AV) functions in a harsh mechanical/hemodynamic environment which modulates its biological responses and adaptations to its surroundings.1,2 The variety of hemodynamic mechanical stimuli such as shear stress, pressure, stretch, and bending regulate valve remodeling, inflammation, calcification, and cell-matrix interactions.3–8 The close correlations between mechanical stresses and heart valve biology have been evidenced by clinical observations and animal studies.2,9,10 These studies have shown that the structural components of the AV undergo constant renewal in response to mechanical loading.9,10

Inflammation, calcification, and ossification are common features of AV diseases.11–13 Although the events leading to these disease states share some similarities with bone mineralization,14,15 their molecular mechanisms remain vastly understudied.16 AV diseases preferentially occur in the aortic side of the valvular leaflets where they are exposed to complex and unstable hemodynamic conditions.17,18 The reasons for this side-specific response potentially associated with the local shear stress environment are not completely understood. Although many studies have been carried out to characterize the response of vascular endothelial cells to shear stress,19,20 studies on valvular endothelial cells are few. The exposure of valvular endothelium to steady unidirectional shear stress has been shown to result in the alignment of the endothelial cells perpendicularly to the flow whereas vascular endothelial cells align parallel to the flow.21 In addition, the transcriptional profiles of both cell types have been compared under static and shear stress conditions and up to 10% of the genes considered in that study were found to be significantly different,22 suggesting clear phenotypic differences between these two cell types in response to shear stress. Despite those differences, it has been shown that the pathological inflammatory responses of the 2 cell types involve similar mediators such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).4 In the context of the valvular response, these mediators are expressed preferentially on the aortic side of the leaflet.

In addition to this side-specificity, AV calcification and inflammation are associated with the expression of TGF-betal (TGF-β1).23 TGF-β1 is a polypeptide member of the TGF-β superfamily which consists of TGF-βs, inhibins, bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), growth differentiation factors, antimullerian hormone, activins, and myostatin.24 TGF-β1 has been shown to trigger calcification in sheep AV interstitial cells by increasing alkaline phosphatase activity.25 Although cell and clinical studies have suggested a potential role for TGF-β1 in the initiation and progression of calcification in AV interstitial cells, studies at the tissue level are lacking. In addition, although it has been shown that exposure of vascular endothelial cells to oscillatory shear stress induces inflammatory responses by the BMP4-dependent mechanisms,26,27 it is not clear whether BMP plays a role in inflammatory responses in AV leaflet in response to altered mechanical environment.

Here, we hypothesized that AV inflammation occurs preferentially in the aortic surface of AV leaflets in a BMP and TGF-β1—dependent manner attributable to the local hemodynamic loading conditions. This hypothesis was tested via 3 sets of experiments focused on the biological response of porcine AV leaflets using either a standard or proosteogenic medium (standard medium supplemented with TGF-β1): (1) to determine the effects of normal and altered shear stresses on cytokine (TGF-β1 and BMP-4) and adhesion molecule expressions in AV leaflets; (2) to investigate the dependence of these adhesion molecules as markers of inflammatory response on TGF-β1; and (3) to investigate the role of BMPs in the shear stress-induced events normally associated with endothelial activation.

Methods

Experimental Groups and Conditions

Five tissue groups were tested in the present study: (1) fresh AV leaflet tissue; (2) tissue exposed to shear stress in standard culture medium; (3) tissue exposed to shear stress in standard medium supplemented with TGF-β1 (0.5 ng/mL) (osteogenic medium); (4) tissue exposed to shear stress in standard medium supplemented with the BMP inhibitor noggin (100 ng/mL); and (5) tissue exposed to shear stress in standard medium supplemented with the TGF-β1 inhibitor SB 431542 (1 μmol/L).

For tissue samples from group 2, each leaflet surface was exposed to normal or altered (ie, pulsatile or oscillatory) shear stress conditions for 48 hours in an ex vivo shear stress device described previously.28 The effects of normal shear stress on the leaflets were investigated by exposing each leaflet surface to its physiological shear stress waveform (ie, physiological ventricular waveform on ventricular surface, and physiological aortic waveform on aortic surface; see Figure 1). To expose AV tissue to altered shear stress conditions (in terms of shear stress directionality), each leaflet surface was exposed to the physiological shear stress waveform experienced by the opposite surface (ie, physiological ventricular waveform on aortic surface, and physiological aortic waveform on ventricular surface; see Figure 1). The surface-averaged physiological shear stress waveforms experienced by the aortic and ventricular leaflet surfaces were obtained from simulations of the physiological pulsatile 3-dimensional flow field through a trileaflet heart valve with prescribed motion using a computational tool designed at Georgia Tech.29–32 Consistent with previous findings,33–34 the predictions (Figure 1) indicate a unidirectional pulsatile shear stress ranging between 0 and 80 dyn/cm2 on the ventricular side, and a bidirectional oscillatory shear stress ranging between −8 and +10 dyn/cm2 on the aortic side.

Figure 1.

Computed physiological shear stress variations experienced by: (a) the aortic; (b) the ventricular surfaces of AV leaflets; and (c) definitions of the normal and altered shear stress conditions generated from them.

Culture Media Description

For details, please see the supplemental materials (available online at http://atvb.ahajournals.org).

Tissue Harvest and Preparation

Porcine hearts were obtained from a local abattoir (Holifield Farms, Covington, Ga). Aortic valve leaflets were excised on-site at the base of the cusp within 10 minutes after slaughter and were transported to the laboratory in sterile, ice-cold Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS; Sigma-Aldrich). Leaflet samples from the fresh control group (group 1) were processed immediately as outlined in the “tissue postprocessing” section. Samples from the 4 other groups were processed according to the following procedure. On arrival in the laboratory, 1 circular 7-mm radius sample was cut aseptically from the basal region of each leaflet in a laminar flow hood. Nine samples were placed in the modified cone-and-plate bioreactor previously designed and validated in our laboratory, exposing either the aortic or ventricular side to the flow. The bioreactor has already been successfully validated with respect to its capability to expose leaflet specimens to desired shear stress variations in a sterile environment.28 Samples were placed flat on cylindrical stainless steel holders and were maintained in position using the clamping system described previously.28 A system continuously perfusing culture medium was added to the setup to provide the leaflet samples with the necessary nutrients and waste removal. The whole setup was placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Tissue Postprocessing and Biological Analyses

For details, please see the supplemental materials.

Semiquantitative Image Analysis

For details, please see the supplemental materials.

Statistical Analysis

For details, please see the supplemental materials.

Results

Normal and Altered Shear Stresses Maintain Leaflet Structure, Endothelium Integrity

After the conditioning of each surface of the tissue samples from group 2 (ie, tissue exposed to shear stress in standard medium) to normal and altered shear stress as defined in the methods section, the specimens were harvested and processed for standard H&E staining. The results (Figure 2) show no noticeable difference in tissue structure, cell concentration, and tissue thickness between the specimens exposed to normal or altered shear stress and the fresh controls. The structure of the leaflets exposed to shear stress displays the typical 3-layer structure of native leaflets with a smooth ventricularis and corrugated fibrosa separated by the spongiosa. More importantly, it was critical to verify that the shear stress conditions imposed by the culture system did not affect the integrity of the endothelial layer of the tissue samples. The von Willebrand factor (vWF) stains (Figure 2) demonstrate the preservation of the endothelial layer in leaflet tissue exposed to any of the four shear stress conditions considered in this experiment. It is interesting to note that although the endothelium lining the aortic leaflet surface is normally exposed to mild oscillatory shear stress levels (± 10 dyn/cm2 as suggested by computational fluid dynamics modeling), it is capable of bearing much higher levels (up to 80 dyn/cm2 as shown in this study). Finally, the maintenance of cell viability was also verified by a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay. Specimens exposed to normal and altered shear stress show percentages of apoptotic cells (between 2.34±0.62% and 5.20± 1.92%) similar to that observed on fresh tissue (3.47±0.32%; supplemental Table II). Therefore, the shear stress conditions considered in the present study were capable of maintaining leaflet structure and cell viability and preserving endothelium integrity.

Figure 2.

H&E and vWF stains on tissue exposed to normal and altered shear stress for 48 hours in standard culture medium (A, aortic surface; V, ventricular surface; cell nuclei, blue; ECM, red; endothelial cells, green).

Altered Shear Stress Increases Expression of Cytokines and Adhesion Molecules on the Aortic Surface of the Leaflet

Immunoshistochemistry for VCAM-1, ICAM-1, TGF-β1, and BMP-4 (Figure 3) performed on tissue from group 2 demonstrated an increased expression of markers normally associated with endothelial activation on the aortic surface of the leaflet exposed to the pulsatile (altered) shear stress waveform. Positive VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and TGF-β1 staining was found in the endothelial layer lining the aortic surface while positive BMP-4 staining was also detected in the endothelial layer and the subendothelial region of the tissue. In contrast, exposure of the aortic surface of the leaflet to its physiological oscillatory shear stress and exposure of the ventricular surface to either normal or altered shear stress did not result in any positive staining as compared to the fresh controls. The results are supported by the semiquantitative analysis that suggests a significant (P<0.05) 4-fold, 2-fold, 6-fold and 4-fold increase in BMP-4, TGF-β1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 expression, respectively, with respect to the fresh controls on the aortic surface exposed to altered shear stress (Figure 3). All other shear stress conditions resulted in levels of marker expressions similar to those detected in fresh controls.

Figure 3.

Expression of cell-adhesion molecules, BMP-4, and TGF-β1 after exposing AV leaflets to normal and altered shear stress for 48 hours in standard culture medium: immunostaining (A, aortic surface; V, ventricular surface; cell nuclei, blue; ICAM-1/VCAM-1/TGF-β1-positive cells, green; BMP-4-positive cells, red); and semiquantitative results (*P<0.05 vs fresh).

TGF-β1 Increases BMP-4 Expression on the Aortic Surface in Response to Altered Shear Stress

The results obtained with tissue from group 2 clearly identified the exposure of the aortic leaflet surface to the pulsatile shear stress waveform (altered shear stress) as the condition yielding the most significant response, and was therefore selected for the subsequent experiments. The exposure of the aortic surface of the leaflet to altered shear stress in the presence of TGF-β1 (group 3) was analyzed via immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 4, BMP-4 and TGF-β1 expressions were enhanced in tissue cultured with the TGF-β1-supplemented medium as compared to both the fresh control and tissue exposed to similar hemodynamics with the standard medium. In the presence of TGF-β1, BMP-4—positive staining can be observed along the fibrosa (arrows, Figure 4) as well as in the spongiosa (arrow heads, Figure 4). TGF-β1—positive staining is localized along the fibrosa. Those qualitative results are supported by the semiquantitative analysis of the 9 tissue specimens that suggests a 9-fold increase in BMP-4 with respect to the fresh controls and more than 2-fold increase with respect to samples conditioned under a similar shear stress using the standard medium (Figure 4). The analysis also indicates a 6-fold increase in TGF-β1 expression as compared to the fresh controls and a 3-fold increase with respect to the measurements in tissue conditioned using the standard culture medium. The absence of alizarin red-positive regions on tissue samples conditioned in the presence of TGF-β1 suggests that 2 days of altered shear stress even in the presence of added TGF-β1 may not have been long enough to induce AV leaflet calcification (see supplemental Figure I). Finally, similarly to the results obtained with standard medium, the combination of altered shear stress with TGF-β1—supplemented medium did not have any significant effect on apoptosis (see supplemental Table II). These results suggest that altered shear stress stimulates TGF-β1 expression, which in turn appears to increase BMP-4 expression in AV leaflets.

Figure 4.

BMP-4 and TGF-β1 expressions after exposing the aortic surface of AV leaflets to altered shear stress for 48 hours in proosteogenic medium: immunostaining (A, aortic surface; cell nuclei, blue; TGF-β1-positive cells, green; BMP-4-positive cells, red); and semiquantitative results (*P<0.05).

BMP-Inhibition Reduces Adhesion Molecule Expression on the Aortic Surface in Response to Altered Shear Stress

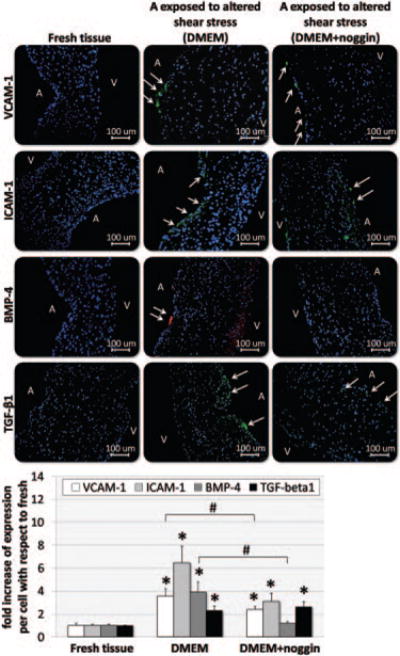

To determine whether BMPs produced by AV tissue in response to the altered shear stress play a key role in the events normally associated with endothelial activation on the aortic surface, the aortic leaflet surface was exposed to altered shear stress using a culture medium supplemented with the BMP inhibitor noggin (group 4). Immunohistochemistry shows that noggin treatment significantly reduced the levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and BMP-4. However, TGF-β1 expression induced by altered shear stress was not affected by the noggin treatment (Figure 5). The TUNEL assay showed that the noggin treatment had no effect on apoptosis of the tissue (see supplemental Table II). These results suggest that BMP4 expression increased by altered shear stress is responsible for the VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 induction in AV leaflet.

Figure 5.

Expression of cell-adhesion molecules, BMP-4, and TGF-β1 after exposing the aortic surface of AV leaflets to altered shear stress for 48 hours in antiosteogenic medium (medium supplemented with noggin): immunostaining (A, aortic surface; V, ventricular surface; cell nuclei, blue; ICAM-1/VCAM-1/TGF-β1-positive cells, green; BMP-4-positive cells, red); and semiquantitative results (*P<0.05 vs fresh; #P<0.05 vs standard medium).

TGF-β1 Inhibition Reduces BMP-4 Expression on the Aortic Surface in Response to Altered Shear Stress

Finally, the role played by TGF-β1 in the inflammatory pathway was investigated by exposing AV leaflets to shear stress in the presence of standard medium supplemented with 1 μmol/L of the TGF-β1-specific inhibitor SB43154235,36 (Sigma; group 5). Immunohistochemistry suggests that blocking the action of TGF-β1 resulted in a dramatic decrease in BMP-4—positive cells, localized only along the fibrosa (Figure 6), as compared to what was observed after using standard medium (group 3). On the other hand, the expression of TGF-β1 was not altered by the presence of its specific inhibitor. These results are confirmed by the semiquantitative analysis that reveals a significant (P<0.05) decrease in BMP-4 expression as compared to the level measured in group 3, but a similar TGF-β1 level. Finally, the TGF-β1 inhibitor did not affect cell viability as determined by the TUNEL assay (see supplemental Table II). These results suggest that TGF-β1 is an upstream regulator of BMP-4 induction in response to altered shear stress in AV leaflets.

Figure 6.

BMP-4 and TGF-β1 expressions after exposing the aortic surface of AV leaflets to altered shear stress for 48 hours in medium supplemented with TGF-β1 inhibitor: immunostaining (A, aortic surface; cell nuclei, blue; TGF-β1-positive cells, green; BMP-4—positive cells, red); and semiquantitative results (*P<0.05).

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to characterize the acute effects of normal and altered shear stresses on cytokine and adhesion molecule expressions in AV leaflets, and to determine whether TGF-β1 and BMP-4 were major mediators of this response. Exposure of each surface of AV leaflets to both normal and altered shear stress conditions revealed that altered hemodynamics (pulsatile shear stress) stimulates inflammatory responses of the aortic surface. Although it has been suggested that low oscillatory shear stress could be a trigger of inflammation on the aortic surface,16,37 the present results suggest that the oscillatory shear stress conditions that the aortic surface is normally exposed to under normal conditions per se did not cause any increase in TGF-β1, BMP-4 and adhesion molecule expressions within the relatively short period (2 days) used in this study. However, the exposure of the aortic surface to the altered shear stress condition used in this study was able to induce the activation of the inflammatory mediators within the same period. Although this finding demonstrates that an altered hemodynamic condition could induce inflammatory responses in AV leaflets, its pathophysiological relevance remains to be determined because it is not clear whether the aortic surface of AV leaflets are exposed to the laminar shear stress waveform in vivo.

In contrast, it is interesting to observe that the inflammatory responses were not found on the ventricular surface exposed to either the normal or altered shear condition. This suggests that the ventricularis surface may be preconditioned or primed for some reasons against the inflammatory responses in response to altered flow conditions. Consistent with earlier findings,38 these side-specific mechano-sensitive inflammatory responses between the two sides of AV leaflets could be attributable to the distinct local mechanical environment to which they are exposed (ie, relatively stable ventricularis flow conditions versus disturbed flow conditions in the aortic surface). In addition, these side-dependent responses could be attributable to different embryonic origins of the endothelial cells lining the aortic and the ventricular surfaces of the leaflet.39,40 Those differences along with the phenotypic differences were also observed between the valvular and vascular endotheliums19,20 and reveal the specificity of valvular tissue.

The increased inflammatory responses observed after exposing the aortic side of the leaflet to nonphysiologic pulsatile shear stress in the presence of TGF-β1 is consistent with an earlier finding that showed a significant increase in the calcific response of sheep aortic valve interstitial cells in vivo cultured with TGF-β1.25 In addition, the absence of calcified nodules in tissue samples exposed to altered hemodynamics in the presence of TGF-β1 may be because the events involved in the calcification pathway occur on a longer timescale (at least 14 days or longer, as suggested by Clark-Greuel et al25) than that considered in the present study. Future studies with longer durations may provide relevant insights into early mechanisms of valve calcification.

The upregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, BMP-4, and TGF-β1 expressions on the aortic leaflet surface in response to nonphysiologic pulsatile shear stress and the downregulation of this response after BMP and TGF-β1 inhibition via noggin and SB 431542 hydrate, respectively, suggest a role for these mediators in the shear stress—induced inflammatory pathway. The upregulation of leukocyte-adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 has already been demonstrated in response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α41 and during human cardiac valve remodeling in utero,42 suggesting a role for the hemodynamic environment in valvular inflammatory processes as well. Previous studies provided some evidence supporting a hypothetical pathway of valve inflammation and calcification. Early events consist of monocyte adhesion, endothelium disruption, and lipoprotein infiltration. The activation of myofibroblasts and the release of TNF-α and TGF-β1 lead, in turn, to increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)−2 and −9 and BMP expressions.43–46 Our current studies using the inhibitors of TGF-β1 and BMP provide further mechanistic insights by which altered shear stress stimulates inflammatory responses in the AV leaflet. In our study, the BMP inhibitor noggin inhibited VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression, whereas the TGF-/1 inhibitor prevented BMP-4 induction without affecting TGF-β1 level. Our results and the literature taken together support the hypothesis that altered shear stress causes TGF-β1 expression which, in turn, causes BMP-4 expression. BMP-4 is known to induce inflammation in vascular endothelial cells.27,47 Consistent with the vascular endothelial cells, our results also suggest that BMP-4 induced in the aortic surface of the AV leaflet by altered shear stress stimulates inflammatory responses as demonstrated by an increase in ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression.

Although the present study only focused on BMP-4, the results do not rule out the potential involvement of other BMPs in those processes. In fact, noggin is not specific to BMP-4 and can also inhibit other BMP members such as BMP−2 and −6. Finally, this study suggests that the mechanistic events leading to AV calcification could be accelerated and therefore studied ex vivo by using a culture medium supplemented with TGF-β1 and BMP-4. This approach, which has already been successfully implemented in vivo on human interstitial cells48 could, if translated at the tissue level, provide invaluable information on the early stages of AV diseases and also serve as a platform for the testing of potential drugs to inhibit AV calcification. By identifying the mechanisms involved in the balance between shear stress and valve biological/pathobiological response, the results described in the present article could help developing potential medical early interventions for the treatment of valvular disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Fotis Sotiropoulos (University of Minnesota) for his aortic valve CFD model, and Holifield Farms (Covington, Ga) for supplying porcine hearts for this research.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by the American Heart Association under the Postdoctoral Research Award 0625620B, and the National Science Foundation through the Engineering Research Center program at the Georgia Institute of Technology under the award EEC 9731643.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Weston MW, Yoganathan AP. Biosynthetic activity in heart valve leaflets in response to in vitro flow environments. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:752–763. doi: 10.1114/1.1397794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willems IE, Havenith MG, Smits JF, Daemen MJ. Structural alterations in heart valves during left ventricular pressure overload in the rat. Lab Invest. 1994;71:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thubrikar M. The Aortic Valve. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fla: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller AM, Cronen C, Kupferwasser LI. Expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules on heart valves: up-regulation in defeneration as well as acute endocarditis. J Pathol. 2000;191:54–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200005)191:1<54::AID-PATH568>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghaisas NK, Foley JB, O’Brian DS. Adhesion molecules in nonrheumatic aortic valve disease: endothelial expression, serum levels and effects of valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2257–2262. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durbin AD, Gotlieb AI. Advances towards understanding heart valve response to injury. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2002;11:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(01)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durbin A, Nadir NA, Rosenthal A, Gotlieb AI. Nitric oxide promotes in vitro interstitial cell heart valve repair. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2005;14:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabkin-Aikawa E, Farber M, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ. Dynamic and reversible changes of interstitial cell phenotype during remodeling of cardiac valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider P, Deck J. Tissue and cell renewal in the natural aortic valve of rats: an autoradiographic study. CardiovascRes. 1981;15:181–189. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.4.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber KT, Sun Y, Katwa LC, Cleutjens JP, Zhou G. Connective tissue and repair in the heart. Potential regulatory mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;752:286–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harasaki H, Hanano H, Tanaka J, Tokunaga K, Torisu M. Surface structure of the human cardiac valve. A comparative study of normal and diseased valves. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1978;19:281–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajamannan NM, Subramaniam M, Rickard D, Stock SR, Donovan J, Springett M, Orszulak T, Fullerton DA, Tajik AJ, Bonow RO, Spelsberg T. Human aortic valve calcification is associated with an osteoblast phenotype. Circulation. 2003;107:2181–4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070591.21548.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YS, Chou YY. Pathogenetic mechanism of senile calcific aortic stenosis: the role of apoptosis. Chin Med J (Engl) 1998;111:934–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speer MY, Giachelli CM. Regulation of cardiovascular calcification. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004;13:63–70. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(03)00130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M ER, III, Gannon F, Reynolds C, Zimmerman R, Keane MG, Kaplan FS. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001;103:1522–1528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butcher JT, Simmons CA, Warnock JN. Mechanobiology of the aortic heart valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008;17:62–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien KD, Reichenbach DD, Marcovina SM, Kuusisto J, Alpers CE, Otto CM. Apolipoproteins B(a), and E accumulate in the morphologically early lesion of ‘degenerative’ valvular aortic stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:523–32. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto CM, Kuusisto J, Reichenbach DD. Characterization of the early lesion of ‘degenerative’ valvular aortic stenosis. Histological and immunohistochemical studies. Circulation. 1994;90:844–853. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levesque MJ, Liepsch D, Moravec S, Nerem RM. Correlation of endothelial cell shape and wall shear stress in a stenosed dog aorta. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:220–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.6.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque MJ, Nerem RM. The elongation and orientation of cultured endothelial cells in response to shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1985;107:341–7. doi: 10.1115/1.3138567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butcher JT, Penrod AM, Garcia AJ, Nerem RM. Unique morphology and focal adhesion development of valvular endothelial cells in static and fluid flow environments. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1429–1434. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130462.50769.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butcher JT, Tressel S, Johnson T, Turner D, Sorescu G, Jo H, Nerem RM. Transcriptional profiles of valvular and vascular endothelial cells reveal phenotypic differences: influence of shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:69–77. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196624.70507.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jian B, Narula N, Li QY, Mohler ER, III, Levy RJ. Progression of aortic valve stenosis: TGF-beta1 is present in calcified aortic valve cusps and promotes aortic valve interstitial cell calcification via apoptosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:457–465. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04312-6. discussion 465–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark-Greuel JN, Connolly JM, Sorichillo E, Narula NR, Rapoport HS, Mohler ER, III, Gorman JH, III, Gorman RC, Levy RJ. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mechanisms in aortic valve calcification: increased alkaline phosphatase and related events. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miriyala S, Gongora Nieto MC, Mingone C, Smith D, Dikalov S, Harrison DG, Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein-4 induces hypertension in mice: role of noggin, vascular NADPH oxidases, and impaired vasorelaxation. Circulation. 2006;113:2818–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.611822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorescu GP, Sykes M, Weiss D, Platt MO, Saha A, Hwang J, Boyd N, Boo YC, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein 4 produced in endothelial cells by oscillatory shear stress stimulates an inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31128–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sucosky P, Padala M, Elhammali A, Balachandran K, Jo H, Yoganathan AP. Design of an ex vivo culture system to investigate the effects of shear stress on cardiovascular tissue. J Biomech Eng. 2008;130:035001. doi: 10.1115/1.2907753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge L, Jones SC, Sotiropoulos F, Healy TM, Yoganathan AP. Numerical simulation of flow in mechanical heart valves: grid resolution and the assumption of flow symmetry. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:709–18. doi: 10.1115/1.1614817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge L, Leo HL, Sotiropoulos F, Yoganathan AP. Flow in a mechanical bileaflet heart valve at laminar and near-peak systole flow rates: CFD simulations and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:782–97. doi: 10.1115/1.1993665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilmanov A, Sotiropoulos F. A hybrid Cartesian/immersed boundary method for simulating flows with 3D, geometrically complex, moving bodies. J Comput Phys. 2005;207:457–492. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilmanov A, Sotiropoulos F, Balaras E. A general reconstruction algorithm for simulating flows with complex 3D immersed boundaries on Cartesian grids. J Comput Phys. 2003;191:660–669. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilner PJ, Yang GZ, Wilkes AJ, Mohiaddin RH, Firmin DN, Yacoub MH. Asymmetric redirection of flow through the heart. Nature. 2000;404:759–761. doi: 10.1038/35008075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies P, Passerini ACS. Aortic valve: turning over a new leaflet in endothelial phenotypic heterogeneity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1331–1333. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130659.89433.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laping NJ, Grygielko E, Mathur A, Butter S, Bomberger J, Tweed C, Martin W, Fornwald J, Lehr R, Harling J, Gaster L, Callahan JF, Olson BA. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-beta type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:58–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watabe T, Nishihara A, Mishima K, Yamashita J, Shimizu K, Miyazawa K, Nishikawa S, Miyazono K. TGF-beta receptor kinase inhibitor enhances growth and integrity of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1303–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thubrikar MJ, Aouad J, Nolan SP. Patterns of calcific deposits in operatively excised stenotic or purely regurgitant aortic valves and their relation to mechanical stress. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:304–308. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmons CA, Grant GR, Manduchi E, Davies PF. Spatial heterogeneity of endothelial phenotypes correlates with side-specific vulnerability to calcification in normal porcine aortic valves. Circ Res. 2005;96:792–799. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161998.92009.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong EJ, Bischoff J. Heart valve development: endothelial cell signaling and differentiation. Circ Res. 2004;95:459–70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141146.95728.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakajima Y, Yamagishi T, Hokari S, Nakamura H. Mechanisms involved in valvuloseptal endocardial cushion formation in early cardiogenesis: roles of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) Anat Rec. 2000;258:119–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000201)258:2<119::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dvorin EL, Jacobson J, Roth SJ, Bischoff J. Human pulmonary valve endothelial cells express functional adhesion molecules for leukocytes. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12:617–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Farber M, Mendelson K, Padera RF, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ. Human semilunar cardiac valve remodeling by activated cells from fetus to adult: implications for postnatal adaptation, pathology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2006;113:1344–1352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santibanez JF, Guerrero J, Quintanilla M, Fabra A, Martinez J. Transforming growth factor-beta1 modulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 production through the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway in transformed keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi T, Hattori S, Shinkai H. Matrix metalloproteinases–2 and –9 are secreted from human fibroblasts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:105–107. doi: 10.1080/00015550310007436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edep ME, Shirani J, Wolf P, Brown DL. Matrix metalloproteinase expression in nonrheumatic aortic stenosis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2000;9:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(00)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soini Y, Satta J, Maatta M, Autio-Harmainen H. Expression of MMP2, MMP9, MT1-MMP, TIMP1, andTIMP2 mRNA in valvular lesions of the heart. J Pathol. 2001;194:225–231. doi: 10.1002/path.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorescu GP, Song H, Tressel SL, Hwang J, Dikalov S, Smith DA, Boyd NL, Platt MO, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein 4 produced in endothelial cells by oscillatory shear stress induces monocyte adhesion by stimulating reactive oxygen species production from a nox1-based NADPH oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:773–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145728.22878.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osman L, Yacoub MH, Latif N, Amrani M, Chester AH. Role of human valve interstitial cells in valve calcification and their response to atorvastatin. Circulation. 2006;114:I547–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.