Clinical Case

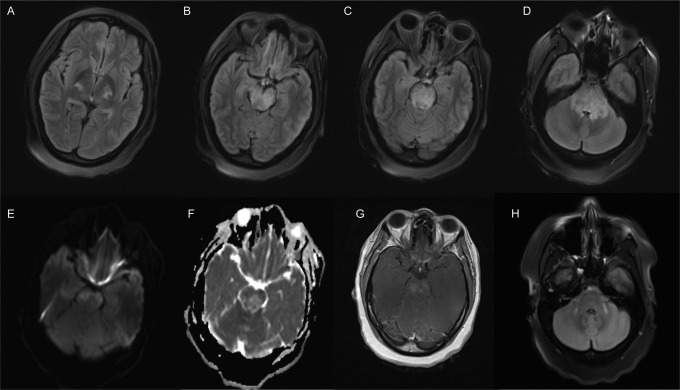

A 39-year-old woman presented with one week of lethargy, diplopia, dysarthria, and ataxia. She had known Behçet’s disease manifesting as recurrent oral and urogenital ulcers. She developed new genital ulcers three weeks before presentation. Examination showed a somnolent woman with variable ocular misalignment, bifacial weakness, dysarthria, and four-limb dysmetria. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated marked brain stem edema with contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion (Figure 1A-G). Given her poor examination and mass effect around the fourth ventricle, she was monitored closely for obstructive hydrocephalus in our neurointensive care unit and treated with intravenous (IV) steroids immediately. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion was not required. Extensive testing including 3 consecutive lumbar punctures with flow cytometry and cytology ruled out other etiologies. CSF analysis was notable for an elevated nucleated cell count (149 cells/μL, 3% neutrophils, 78% lymphocytes) normal protein, glucose, and immunoglobulin G index with no oligoclonal bands. After stabilization, she was transitioned to oral steroids and monthly pulses of IV cyclophosphamide with significant improvements on examination and neuroimaging. Follow-up MRI one month after presentation showed improvement in mass effect, T2 hyperintensities, and contrast enhancement (not shown). Further improvements were seen after 6 months of IV cyclophosphamide (Figure 1H). Central nervous system (CNS) Behçet’s disease may manifest as a subacute inflammatory rhombencephalitis in the appropriate clinical context. Other presentations of CNS Behçet’s disease include aseptic meningitis and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.1,2 It is imperative to differentiate this disorder from other causes of rhombencephalitis including infectious and neoplastic etiologies, so that the appropriate course of treatment can be undertaken.

Figure 1.

Brain MRI on presentation (A-G) and after 6 months (H). A to D, FLAIR sequences demonstrated an edematous hyperintense lesion within the brain stem at multiple levels, bilateral cerebellar peduncles (D) and bilateral thalami (A). E to F, There were patchy areas of restricted diffusion and contrast enhancement (G). H, Follow-up MRI after IV/oral steroids, and 6 months of IV cyclophosphamide showed improvement in T2 hyperintensities (vs D). FLAIR indicates fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Al-Araji A, Kidd DP. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kocer N, Islak C, Siva A, et al. CNS involvement in Neuro-Behçet syndrome: an MR study. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1015–1024. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]