Abstract

This article presents cross-country comparisons of trends in for-profit nursing home chains in Canada, Norway, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States. Using public and private industry reports, the study describes ownership, corporate strategies, costs, and quality of the 5 largest for-profit chains in each country. The findings show that large for-profit nursing home chains are increasingly owned by private equity investors, have had many ownership changes over time, and have complex organizational structures. Large for-profit nursing home chains increasingly dominate the market and their strategies include the separation of property from operations, diversification, the expansion to many locations, and the use of tax havens. Generally, the chains have large revenues with high profit margins with some documented quality problems. The lack of adequate public information about the ownership, costs, and quality of services provided by nursing home chains is problematic in all the countries. The marketization of nursing home care poses new challenges to governments in collecting and reporting information to control costs as well as to ensure quality and public accountability.

Keywords: Ownership, profitability, cost, quality, accountability

Marketization of health and social service organizations includes the ideas of privatizing funding streams and commercializing services.1 The use of competing private providers to provide health services was widely supported by the concept of new public management that introduced new principles, practices, and regulations into the public sector in the 1990s.1 These ideas of competition and customer choice have been widely adopted in the long-term care sector and have dramatically increased the growth of for-profit nursing homes. The provision of long-term care by for-profit providers, however, is a growing concern. For-profit incentives are directly related to poor quality,2–4 where facilities operate with lower staffing and more quality deficiencies (violations) compared with nonprofit facilities.5–7 In the United States, nursing homes with the highest profit margins have been found to have the poorest quality.8

Chains of nursing homes (ie, that own or manage 2 or more facilities) began to grow in the United States and Canada in the 1970s, and they became a prominent organizational form in the 1990s.9,10 Growth occurred primarily through the acquisition of existing facilities and other chains.9,11 For-profit chains aim to improve profitability by economies of scale, standardization of services, brand name recognition and visibility, and organizational survival in competitive environments.9–11 Increasingly owned by large private companies and private equity funds, for-profit nursing home chains have changed the amount, type, and quality of services delivered.5–12

Study Research Aims

Although previous studies have examined for-profit nursing home chains and marketization in individual countries, no study has examined the trends and variations across countries. This article first presents cross-country comparisons of contextual differences and trends in growth of for-profit nursing home chains in Canada, Norway, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States. Second, the study examined the 5 largest for-profit chains in terms of their (1) ownership, (2) corporate strategies, (3) costs, (4) quality, and (5) accountability. The study uses secondary documents from multiple public and private sources to describe chains across countries.

These 5 industrialized countries were selected because the authors are part of a larger international collaborative study of nursing homes with access to extensive documents and data from reliable sources. Because of the contextual variations in demographic trends, market structure, and government funding, we expected to find both differences and commonalities across the countries. Norway and Sweden have similar welfare models and marketization began later than other countries so that for-profit nursing home chains may have less impact on their nursing home services.

Background: Growth of For-Profit Nursing Home Chains by Country

Canada had an industry of small owner-operated homes which began to change with the development of provincial government involvement in the licensing and payment for services. In Ontario, nursing homes were required to be licensed in 1966, and in 1972, hospital insurance was extended to cover nursing homes.9 These changes encouraged the development of and reliance on for-profit nursing homes and chains because of economic restraints on government funding and government’s limited role in the regulation and enforcement of quality.9 For example, the Ontario government made policy changes that favored the growth of chains in the mid-1990s. These included accepting low bids for contracts, publicly financed capital funding, legislation that eliminated minimum staffing standards, and a revised payment system that allowed companies to maintain their profits without a return to government.13

Norway provides comprehensive health and social care services to its population, where hospital services are paid for at the national level and municipalities are responsible for primary care and long-term care (nursing homes, special housing, and home care).14 This arrangement to give decentralized care responsibility to 429 municipalities was established in 1982 and supported again in 2011, allowing municipalities flexibility on how to plan and organize services. In the late 1990s, inspired by new public management and the example of Sweden, the ideas of marketization promoted the separation of purchasers and providers, free choice, and benchmarking. Although a few nursing home services were contracted out in the late 1990s, only 7% of Norway’s municipalities had outsourced nursing homes after competitive tendering in 2012.14

Sweden also provides health and eldercare services on a comprehensive, publicly financed basis for all its citizens according to their needs rather than ability to pay. The responsibility to organize care services rests with the 290 highly independent municipalities.15 Since the early 1990s, the Swedish eldercare sector was influenced by new public management with legislation giving local authorities the freedom to determine their own organization and the ability to contract with private providers, which one-third of the Swedish municipalities chose to do in 2012. Since the 1990s, the private provision of publicly funded services has grown substantially including for-profit providers and chains.15

After World War II, the United Kingdom established the National Health Services (NHS) which provided free universal health care to the population in hospitals, primary care, and community health services, whereas local authorities provided means-tested social services including residential and home care.16 In the 1980s, the government enacted policies which led to the closure of NHS long-stay hospitals and growth of the for-profit private nursing home sector. The NHS and Community Care Act of 1990 devolved the funding responsibility of long-term care to local authorities and continued to transfer previously free NHS care into means-tested social care. To manage the constraints of their budgets, local authorities targeted services to those with the greatest need.16 These policies contributed to the growth of the for-profit industry and chains in the United Kingdom.17 The trends were a product of the partial privatization of the NHS in the United Kingdom that ultimately resulted in increased costs, less efficient services, and the erosion of the principle of universal services free at the point of delivery.17

Nursing homes in the United States grew out of the almshouse system for the poor in the 1800s, which were converted to boarding homes in the 1900s for residents to pay their own care, especially after the enactment of the federal Old Age Assistance law in 1915 and the Social Security Acts in 1935.18 Between the 1920s and the 1950s, the number of US nursing homes grew dramatically and ownership changed from small largely nonprofit providers to most of the for-profit companies. After 1965, the growth in nursing homes and the shift to for-profit companies were fueled by a steady source of revenues after the enactment of the Medicare and Medicaid programs and the Federal Housing Authority loan guarantee program.18 Major growth occurred in the 1990s with many acquisitions and mergers by chains.11,19

Methodology

Specific research aims

This descriptive and explorative study had 2 specific research aims. The first aim was to describe the contextual differences and the privatization and the growth trends of nursing home chains in 5 industrialized countries in the 2005–2014 period. The second aim was to describe the 5 largest for-profit chains in each country in terms of their (1) ownership, (2) corporate strategies, (3) costs, (4) quality, and (5) accountability in the most recent period of 2015–2016. We included historical data on ownership since 2005 where data were available to identify trends. In each country, the 5 largest for-profit nursing home chains were selected based on number of beds, except in Norway only had a total of 4 chains.

Study design and data collection

For the first aim, descriptive data for 2005 and 2014 were collected from each country (the most recent available data). Background documents were obtained from government sources describing the population, nursing homes and beds, ownership/management, chains, occupancy rates, and government expenditures. For the second aim, we collected descriptive data on the 5 largest chains in each country using multiple secondary sources including public and private documents from government, corporate reports, market reports, media reports, and other sources for the most recent time period (2015–2016). The secondary sources of data collected were cited in the text and tables.

For profitability, we used standard financial measures including both the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization, and restructuring or rent costs (EBITDAR) which is the earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA), which is EBITDAR minus lease expenses. Data on quality were only available in the province of Ontario, Canada, and the United States. In Canada, government reports were used to identify deficiencies (regulatory violations) to indicate quality. In the United States, publicly available government administrative data were obtained to examine staffing and deficiencies for each nursing home chain.20

Limitations

It should be noted that there were many limitations in the quality and the availability of data in each countries and from the largest nursing home chains because most data were not publicly available. Data from private industry reports could not be confirmed and data from the large nursing home chains often varied by source. Thus, the findings represented the authors’ best efforts of compiling information on companies from recent sources.

It would have been desirable to have trend data over a longer time period by countries as well as data for the large chains. Unfortunately, historical trend data on nursing homes chains were not readily available except for publicly reported companies. Data on beds and homes were available for some chains in Canada and the United States for 2005 from private sources (not government) but were very limited for the United Kingdom. Some chain data on employees and revenue growth from private sources were available in Norway and Sweden, and several companies were new since 2005. It should also be noted that generally nursing homes do not report on homes that are owned and those that are managed so the term ownership in this article includes both homes that are owned and managed.

Data analysis

The overall trend data were analyzed separately for each country and for the 5 largest chains in each country. For each chain, we analyzed the following: (1) type of corporate owners and changes over time, their organizational structure if available, their growth since 2005, and their market share in each country; (2) corporate strategies including the separation of property from operational companies, diversification in companies and services;, location of services, and tax havens; (3) cost information including revenues and profitability; (4) quality indicators including government sanctions, staffing levels, and regulatory violations (deficiencies) (where available); and (5) public accountability and transparency in terms of access to ownership, financial, and quality information. Finally, the findings in each country were compared with identify commonalities and differences related to the growth and impact of the 5 largest for-profit chains and policy issues were discussed.

Findings

Comparative context

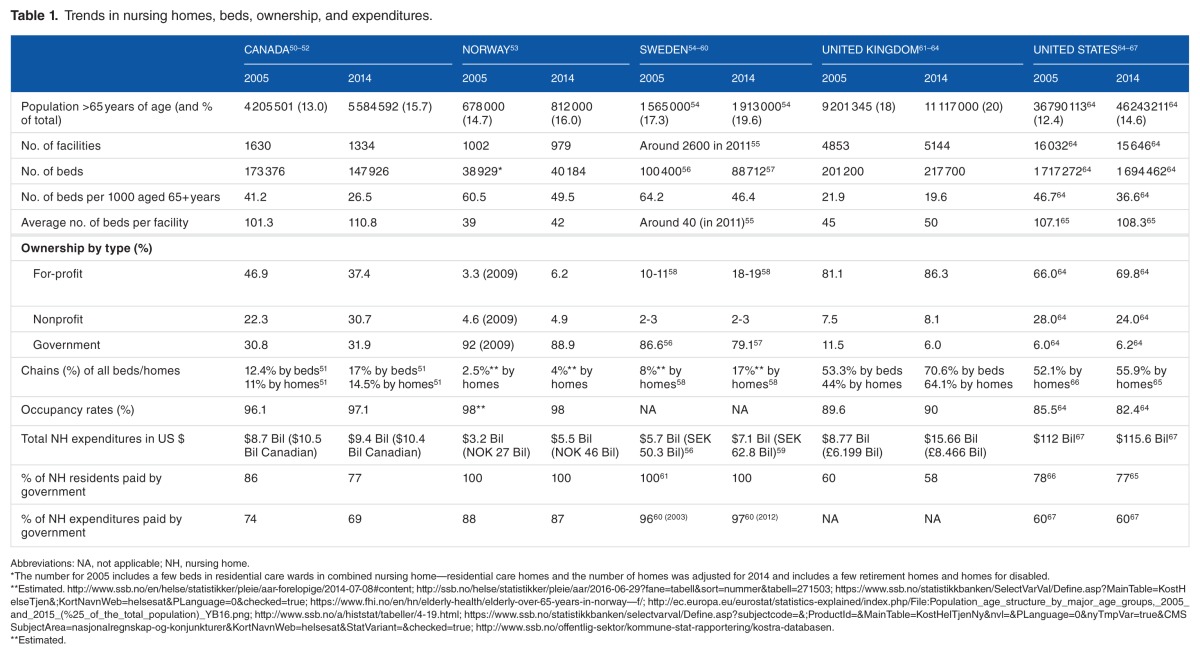

All 5 counties experienced growth in the population aged 65 years and above between 2005 and 2014, with the highest proportion of the aged population in the United Kingdom and Sweden (20%) (see Table 1). The number of nursing home beds per 1000 population, however, declined during period in all the countries with the greatest declines in Canada and Sweden. In 2014, the United Kingdom had the lowest overall rate of beds per 1000 aged population, and Norway and Sweden had the highest rates. Occupancy rates were highest in Norway (98%) and remained similar between 2005 and 2014 in all countries, except in the United States which declined to 82%.

Table 1.

Trends in nursing homes, beds, ownership, and expenditures.

In 2014, for-profit ownership of nursing homes was the highest in the United Kingdom (86%) and the United States (70%) and substantially lower in Canada (37%), Sweden (18%-19%), and Norway (6%) (see Table 1). The proportion of for-profit ownership increased in all countries between 2005 and 2014 except in Canada which fell by 20%. The largest increases in for-profit ownership were in Norway and Sweden. Government ownership of nursing homes fell between 2005 and 2014 in the United Kingdom and Sweden and remained similar in Canada and the United States. Data on ownership and management were combined, and some companies in Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have contracts with local government to manage nursing homes. In 2014, government operation of nursing homes was 89% in Norway and 79% in Sweden compared with about 6% in the United Kingdom and the United States.

In 2014, for-profit nursing home chains were the dominant providers in the United Kingdom and the United States compared with 17% of homes in Sweden, 14.5% in Canada, and only 4% in Norway (Table 1). The growth in chains occurred in all countries where data were available, with a large increase in the United Kingdom (from 44% to 64% of homes) and over double the percentage in Sweden and almost double in Norway since 2005.

Total expenditures for nursing homes remained similar in Canada and the United States between 2005 and 2014, whereas increasing in the United Kingdom, Norway, and Sweden (Table 1). The proportion of nursing home residents funded by government was highest in both Norway and Sweden where 100% of residents are funded by government. In Canada, United Kingdom, and United States, the percentage of residents funded by government decreased slightly between 2005 and 2014, with the greatest decrease in Canada (from 86% to 77%).

Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in Canada

Ownership

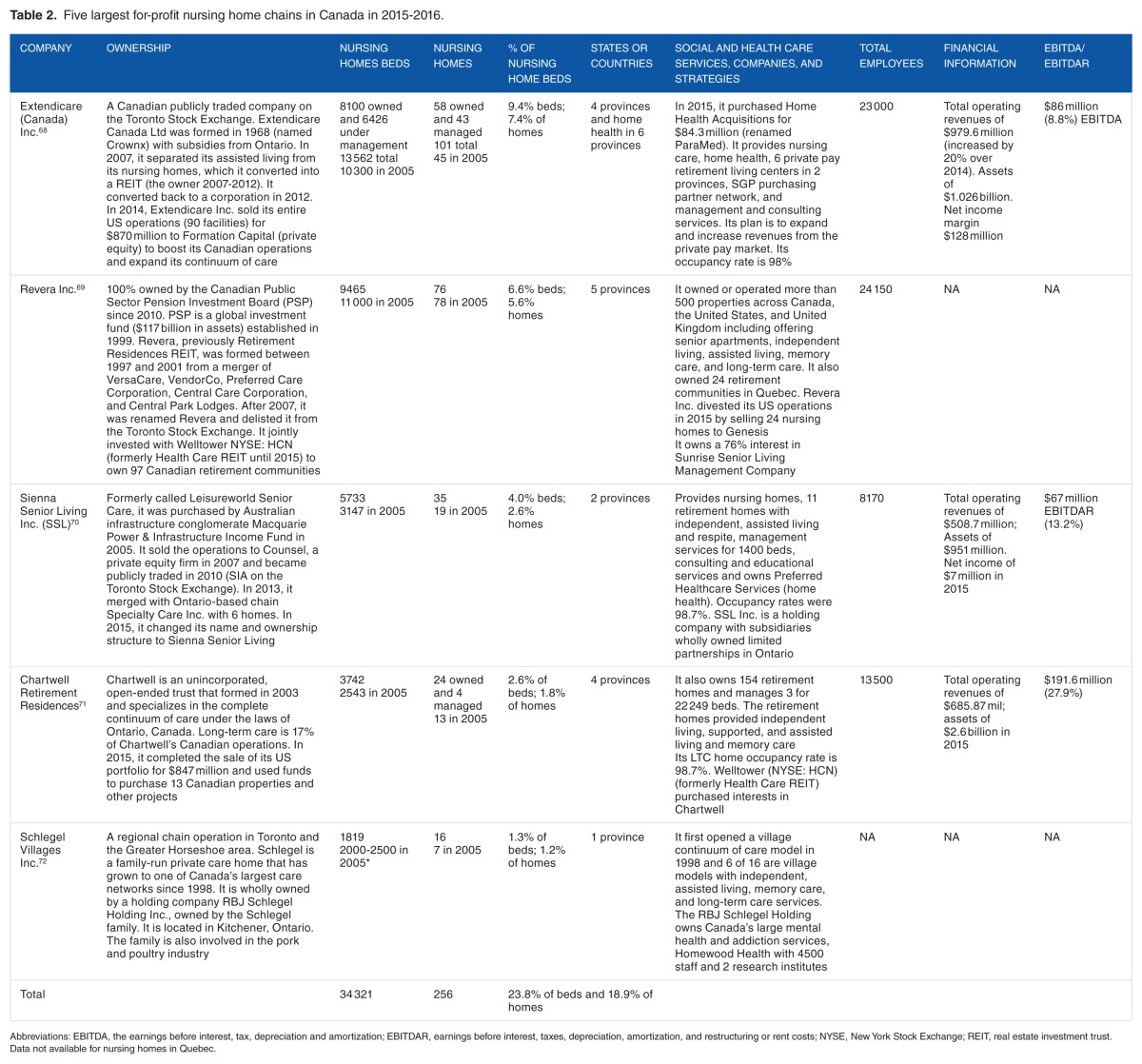

Extendicare was the largest for-profit nursing home chain in Canada with 13 562 beds and 101 nursing homes in 2015 (Table 2). In 2013, it became a publicly traded company on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX). Sienna Senior Living Inc., the third largest firm, was also a publicly traded company. Chartwell Retirement Residences, the fourth largest chain, was owned by a trust and had public reporting. In contrast, Revera Inc. (the second largest), 100% owned by the Canadian Public Sector Pension Investment Board became a private company in 2007 and was delisted from the TSX. Schlegel Villages (the fifth largest) was privately owned by a family. As private companies, Revera and Schlegel Villages did not have detailed financial reports. One chain (Schlegel) had a holding company and all had complex corporate structures with subsidiaries and related party companies and/or divisions.

Table 2.

Five largest for-profit nursing home chains in Canada in 2015–2016.

Three of the chains had changes in ownership and/or organizational structures over the past decade but the 5 chains retained the same relative size (rank order) since 2005. Three of the 5 companies (Extendicare, Sienna Senior Living Inc., and Chartwell) grew steadily in terms of nursing home beds and homes primarily by acquisitions and mergers between 2005 and 2015–2016. Revera Inc. had a reduction in beds and a slight reduction in facilities, and Schlegel Villages had a slight reduction in beds but doubled its nursing homes between 2005 and 2015–2016. The largest 5 chains controlled 23.8% of beds and 18.9% of nursing homes in Canada.

Corporate strategies

Canadian nursing home chains have been involved in real estate investment trusts (REITs). The Extendicare company was converted into a REIT (from 2007 to 2012) and then was converted to a publicly traded company in 2012. Both Revera Inc. and Chartwell jointly owned properties with Welltower (New York Stock Exchange [NYSE]: HCN), a REIT that owned more than 1400 properties in major, high-growth markets in the Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with $29 billion in assets.21 Three of the largest chains have separated their operating nursing homes from their property and used leaseback arrangements with property companies.

The 5 chains were all diversified in owning retirement homes, assisted living facilities, memory care, development companies, purchasing services, home health care, and 1 chain owned research institutes. Two of the 5 chains provided management services to their companies and other homes. Retirement homes and assisted living facilities were a major target for growth primarily because they focused on the private pay market and were less regulated in terms of both starting up companies and operations.

Reflecting Canada’s sharp overall decline in nursing home beds and its low bed to population ratio, compounded by strict licensing laws in Ontario, all the nursing home chains showed high occupancy rates with little or no market competition. These chains have been able to take advantage of the limited bed supply and government funding and subsidies to rapidly expand their homes and beds. All but one chain operated in more than one Canadian province. None of the Canadian companies appeared to be located in tax havens.

Of the 5 largest Canadian for-profit chains, Extendicare and Revera owned nursing homes in the United States until they divested in 2015. Extendicare in the United States had 90 nursing homes and more than 12 000 beds (the ninth largest US chain) before it sold its homes in 2015.22 The decision to sell may have been related to Extendicare’s payment of $38 million to the US Department of Justice and 8 states to resolve allegations of billing Medicare and Medicaid for substandard nursing services and for medically unreasonable and unnecessary therapy and entered into a 5-year chain-wide Corporate Integrity Agreement with the government in 2014.23

Costs

Revenues ranged from $509 million to $980 million in Canadian dollars in the 3 Canadian chains that reported their financial data. Their net income showed high rates of return (8.8%, 13.2%, and 27.9%) for 2015–2016 (Table 2). These high profits had been sustained over time. From 2007 to 2012, Extendicare reported an average annual profit margin of 9.6%, Chartwell reported 12.6%, whereas Sienna Senior Living Inc. (Leisureworld) reported 11.8% from 2010 to 2012 (no table shown).

Quality

The quality of the largest for-profit chains was examined in Ontario where data were available. Corporate chains made up a larger share of the for-profit market in Ontario (82%) than in Canada overall and have a strong political influence.24 Many chains have their headquarters in the greater Toronto area where the province has the largest population, has the TSX and a large Toronto financial district, and has a strong infrastructure for supplier networks that is well integrated with US Great Lakes region.

The 5 largest for-profit nursing home chains in Ontario had a total of 5759 deficiencies in their 154 nursing homes (37.4 deficiencies per home) in the 2011–2015 period compared with an average of 35.5 for all nursing homes. For-profit homes in total had an average of 37.3 deficiencies per home, 35.6 for nonprofits, and 33.5 for municipal homes in 2015 (the differences were not significant).

The findings in this study were consistent with a study in Ontario and British Columbia. The study found that for-profit-chain facilities had significantly higher rates of resident complaints compared with nonprofit and public facilities.25 Another recent study of Ontario long-term care homes found that for-profit nursing homes, especially chains, provided significantly fewer hours of registered nurse and registered practical nurse care, after controlling for resident care needs.26

Public accountability

As noted above, only 3 of the largest chains had public reporting so that annual reports were available. Although government data on individual facility deficiencies were available for analysis by chains, government reports on specific chain ownership, costs, and quality were not available.

Largest For-Profit Chains in Norway

Ownership

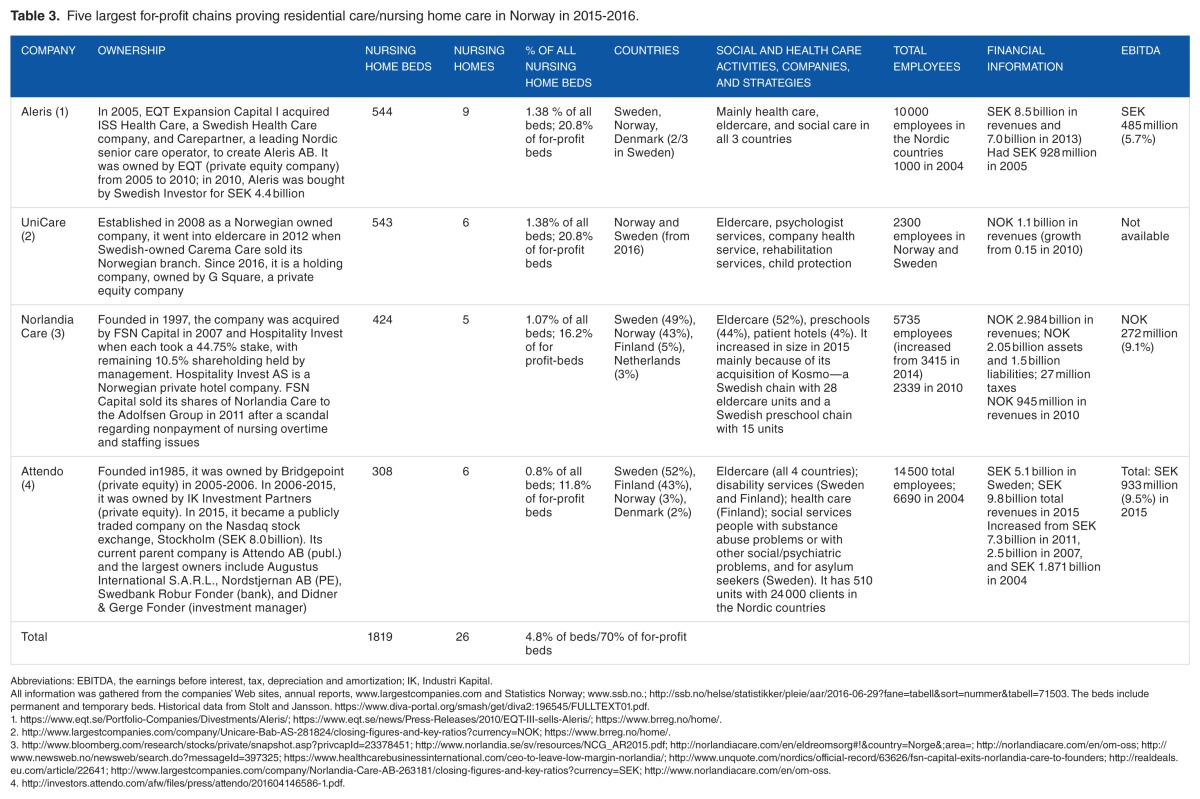

In 2015–2016, there were only 4 chains in Norway with 26 nursing homes and 1819 beds (Table 3). Two of 4 Norwegian chains were privately owned (Aleris and Norlandia) (although Norlandia had private equity owners), 1 (UniCare) was owned by a private equity company, and 1 was publicly traded (Attendo) with some private equity owners. These large for-profit chains accounted for 4.8% of total nursing home beds and almost 70% of the for-profit nursing home beds.

Table 3.

Five largest for-profit chains proving residential care/nursing home care in Norway in 2015–2016.

Since 2005, there has been a gradual shift away from a dominance of private equity companies primarily because of nursing home scandals and rumors of stricter government regulations. In 2011, Adecco, a Swiss-operated for-profit chain operating some homes in Norway, was reported by care workers, trade unions, and the media to be systematically violating worker’s rights for overtime and holiday pay and pensions, and staffing levels for unskilled workers were lower than their contract agreements. All of Adecco’s nursing homes were forced out of the care sector by municipalities in Norway in 2011.

After Swedish-based Carema Care also was involved in a major scandal in 2011 regarding understaffing and poor care, it sold its Norwegian branch of nursing homes to UniCare, a Norwegian company formed in 2008. In addition, after Norlandia’s nursing homes in Norway were also involved in a scandal regarding nonpayment of nursing overtime and staffing issues, its private equity owner sold its shares to the Adolfsen Group (another private equity company) in 2011.

The 4 chains were characterized by multiple changes of ownership. The Swedish company Attendo was rather typical. Originally called Partena Care, it first contracted to provide nursing home care in Norway in 1997. Attendo bought Capio Care in 2004, a company running 3 nursing homes in Norway. In 2005, Attendo was sold to the British private equity fund Bridgepoint. Bridgepoint, in turn, sold Attendo to the Swedish private equity fund Industri Kapital in 2006. In 2015, Attendo became a limited company and publicly traded. Data on growth in beds and nursing homes were not available, but all 4 companies reported a substantial growth in revenues and employees over the past 5 to 10 years.

The chains also had complex ownership structures. For example, Norlandia reported multiple individual and corporate owners, subsidiary companies, holding companies, and related companies. A major Norwegian union, Fagforbundet, has recently been campaigning for public disclosure of what their spokespeople label “the real owners.”

Corporate strategies

The 4 nursing home chains had diversified their services by operating companies involved in health and social care, child protection, preschools, patient hotels, and other services. They each had operations in 2 to 4 countries. Previously Attendo and Aleris had reported they were based in tax havens, but current data were not available.

Costs

The 4 companies reported employees ranging from 2300 to 14 500 in 2015–2016 and revenues that ranged from NOK/SEK 1 to 8 billion. Profit margins (EBITDA) were listed at 6% to 9.5% for 3 companies, and 1 company did not report data.

Quality

Following the scandals in for-profit chains described above, the city governments of Oslo and Bergen, the 2 biggest cities in Norway, decided in 2015 not to renew management contracts with for-profits in the care sector. For this reason, the share of for-profit nursing home beds in Norway is expected to decline in the near future. In contrast to Sweden, nursing home buildings and property in Norway are owned by municipalities. None of the for-profit chains owned buildings or other material assets in Norwegian residential care, which makes it easier to end contracts.

Public accountability

Only 2 of the largest chains (Norlandia and Attendo) made public reports available in English. The other 2 chains made reports available on an industry Web site in Norwegian. Some municipal governments have contracts with private companies to provide nursing home services, but they do not make ownership, financial, and quality data publicly available on individual nursing homes or chains.

Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in Sweden

Ownership

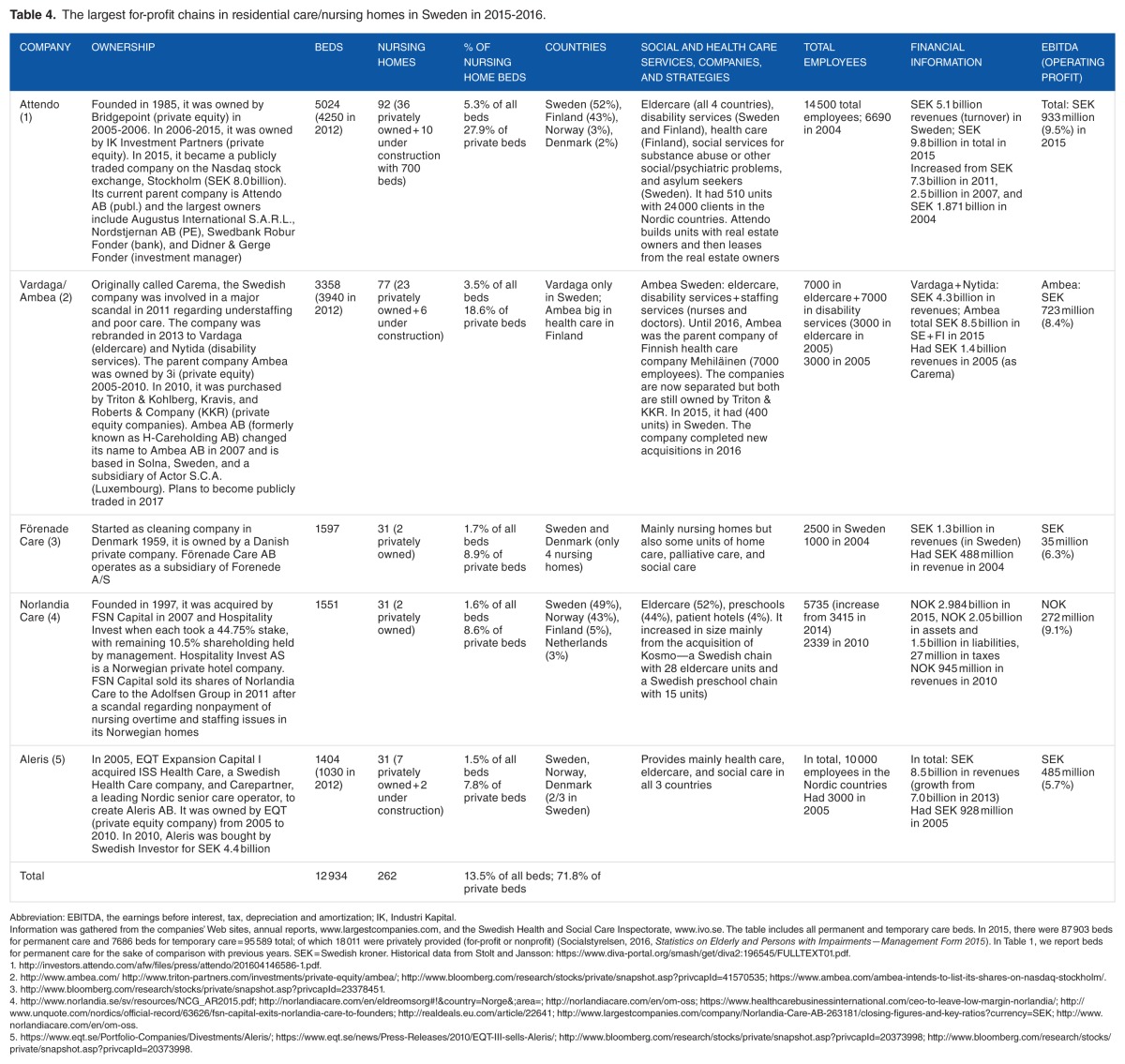

In Sweden, large international corporations increasingly dominate the market. Starting in 2005, these corporations were bought up by private equity firms (Table 4). Attendo was the largest chain in total beds and the only company that was publicly traded, starting in 2015. Vardaga/Ambea became the second largest chain after Carema was purchased by Triton to be part of Ambea Group in 2010 through a competitive process from the 3i company on a partnership basis with another private equity company. In 2011, Carema faced a significant media scandal when it was reported to have inadequate numbers of registered nurses, undernourished residents, and a high number of resident deaths. The poor quality of care and scandal was followed by internal turmoil and employee turnover. Triton’s restructured the business and sold underperforming services and the rebranded Carema as Vardaga/Ambea, with 2 distinct divisions: Vardaga for elderly care and Nytida for disabled care in 2013.27 Since then, Ambea Sweden was separated from the Finnish Mehiläinen Group into an independent entity and it announced plans to become publicly traded in 2017. All the companies have a complex ownership structures.

Table 4.

The largest for-profit chains in residential care/nursing homes in Sweden in 2015–2016.

Of all nursing home care in Sweden, 12 934 permanent and temporary beds (13.5% of all beds) were provided by the 5 largest chains in 2015. This corresponded to 71.8% of the private beds and the 10 largest chains provided 86.8% of the private beds.28 Half of the beds in for-profit homes were run by the 2 largest corporations, Attendo (92 homes, 5024 beds) and Ambea (77 homes, 3358 beds) (Table 4).

Attendo had 19 000 total employees, Ambea had 14 000, and Aleris had 10 000. The number of employees has more than doubled for Attendo, Ambea/Vardaga, Förenade Care, and Aleris. Revenues have grown considerably from all types of activities and in the Nordic countries since 2004–200529 (see Table 4). Data on growth in beds and nursing homes over the past 10 years were not available.

Four in the top 5 in 2015–2016 (Attendo, Vardaga/Ambea, Förenade Care, and Aleris) have changed names since they were founded.29 Norlandia was not active in Sweden in 2005, but the company grew rapidly after they purchased a company with 28 nursing homes in Sweden (see Table 4). These large chains have grown mainly by acquisition of other companies.

Corporate strategies

Nursing home chains increasingly have been building their own nursing homes and selling beds to various municipalities. For example, Attendo has built its own care homes in cooperation with construction and real estate companies that own the properties, and lease the buildings to Attendo, normally for 10 to 15 years. Attendo contracts with municipalities to provide nursing home care and have the municipalities pay for the building costs. The building of private homes is a new phenomenon in Sweden. Currently, the 2 largest chains have built more than one-third of the privately owned homes, and they have another 16 homes under construction.

Previously, virtually all privately provided residential care was outsourced after competitive contracting (tendering), which made it relatively easy for a municipality to end a contract if they were not satisfied with the quality. If municipalities want to end contracts with privately owned homes, they must find new homes for residents, similar to the situation in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The more facilities built by private companies, the more dependent the municipalities are on their contribution. Consequently, it is more difficult for the government to prohibit profit-making in residential care, and a government commission is presently studying this issue.

All the 5 largest chains operated in 2 to 4 countries. Three of the top 4 companies (Attendo, Aleris, and Norlandia) were among the top 4 in Norway, and in both countries, they have been increasingly active in other areas such as health care, disability services, and recently arrived minors seeking asylum. Three companies (Attendo, Ambea, and Aleris) were previously reported to be based on tax havens, but current data were not available.

Costs

Some large companies reported low assets, high debt, and paid minimal taxes (eg, Norlandia). Financial data were not publicly available except for Attendo (a public company) and Norlandia. Revenues for the 5 largest companies ranged from SEK 1.3 billion to 9.8 billion. Profit margins (EBITDA) for the 5 companies were reported to range from 6% to 9.5% in 2015–2016. These large profit margins have raised political concerns in Sweden where a government commission is investigating the possibilities of limiting profit-making in welfare services.

Quality

No public data were available on quality in Swedish nursing home chains for this study. A recent study of nursing homes operated by private equity companies found that they had higher revenue growth and profit margins than other nursing homes.28 These companies had lower numbers of employees per resident and higher proportions of staff employed on an hourly basis, but specific differences in quality were not identified.28 The previous scandals in care quality at Carema (now Vardaga/Ambea), Norlandia, and other for-profit homes in Sweden, however, suggest that staffing and quality problems may be an ongoing concern to the municipalities.

Public accountability

As noted above, 3 of the largest chains (Attendo, Ambea, and Norlandia) publicly reported on their companies, and one other company made its annual report available on an industry Web site. Some municipal governments have contracts with private companies to provide nursing home services, but they do not make ownership, financial, and quality data publicly available on individual nursing homes or chains.

Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in the United Kingdom

Ownership

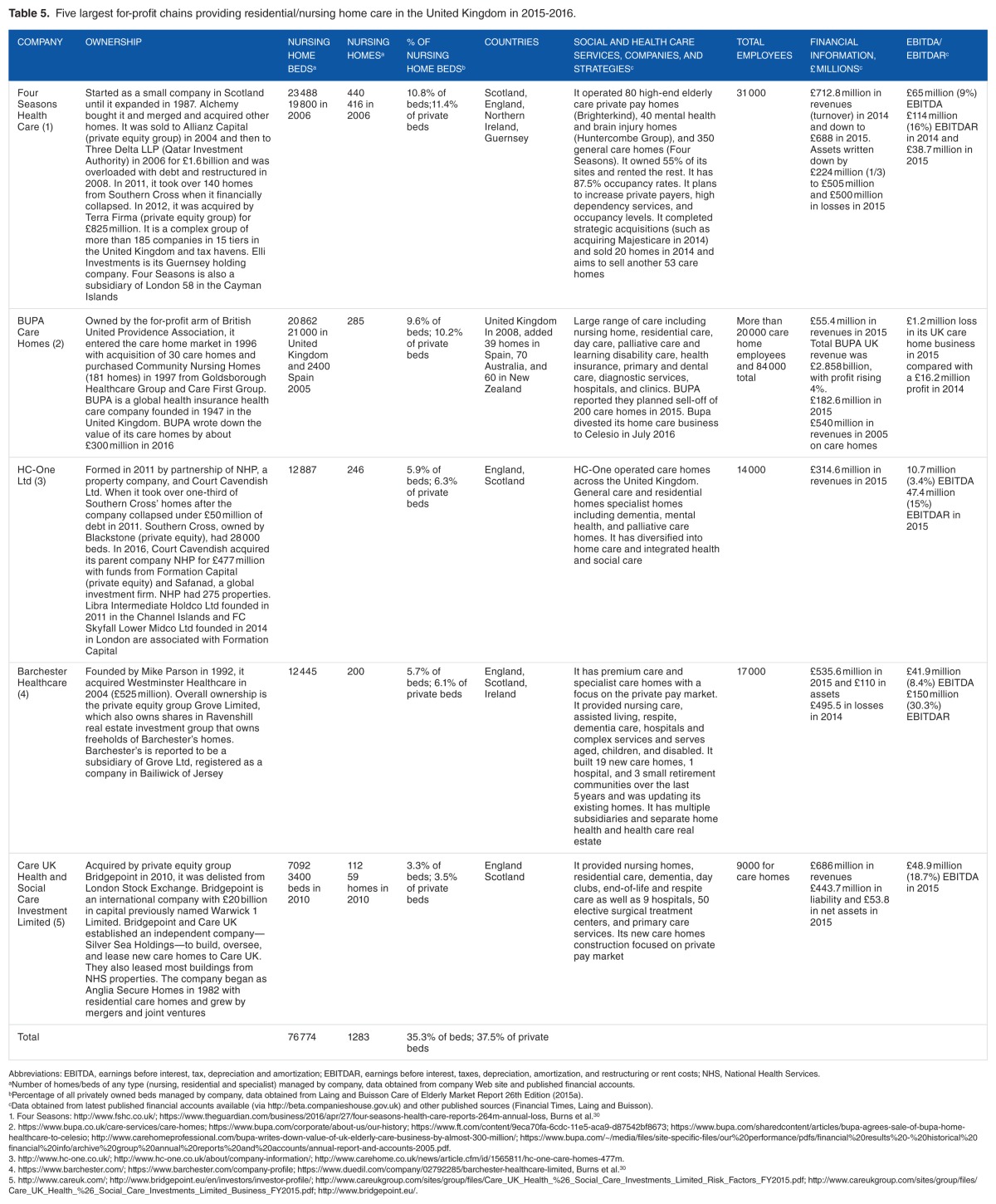

The 5 largest providers of residential beds in the United Kingdom (Four Seasons Health Care, Bupa Care Homes, HC-One Ltd, Barchester Healthcare, and Care UK Health and Social Care Investment) accounted for 35.3% of available residential beds in 2015–2016 (Table 5). All except Bupa Care Homes were private limited companies, ultimately controlled and owned by private investment and equity groups registered in tax havens such as Guernsey, Jersey, and Cayman Islands. Bupa Care Homes was owned by the for-profit arm of the British United Province Association, a global insurance company.

Table 5.

Five largest for-profit chains providing residential/nursing home care in the United Kingdom in 2015–2016.

Most of the growth of the large UK chains was in the early 2000s. Prior to 2008, expansion was driven by mergers and acquisitions funded by debt, with private equity groups attracted by stable government-funded income, increasing property prices of homes and advantageous demographic changes in 2015–2016. In 2011, the largest UK nursing home chain, Southern Cross (founded in 1995), went bankrupt after its purposeful build-up of large debt to fund growth resulted in unsustainable debt repayment. Most of Southern Cross’ facilities were sold to Four Seasons making it the largest chain. A third of Southern Cross’ facilities were also purchased by HC-One Ltd, a new private company founded with equity investors in 2011.

Although historical data were not available for Barchester and HC-One was a new company, 2 companies showed growth (Four Seasons and Care UK) and BUPA had a growth in beds between 2005 and 2015–2016. BUPA had a loss in its UK care business in 2015 and reported a plan to sell most of their care homes (Table 5). The 5 companies all had complex organizational structures with the most prominent being Four Seasons, which reportedly has more than 185 companies with holding companies registered in Guernsey and the Cayman Islands.30

Corporate strategies

The largest chains have used sale and leaseback arrangements, by splitting the operating and property companies in to separate groups and the leasing the property from the property companies sometimes at artificially high rates.30 After the 2008 global financial crisis, with a fall in property prices and income, the focus has been on diversification and restructuring—separating operations and property ownership and selling of less profitable care homes and the development of new care homes in more affluent areas. Moreover, recent strategies have been to focus on serving the private pay market.

The companies have diversified and expanded into independent living and residential care, day care, palliative care, and other long-term care services. Some companies also provide primary care, hospitals, and clinics. The 5 large companies operated homes in England, Scotland, and Ireland, whereas BUPA had operations in Spain, Australia, and New Zealand.

All except BUPA Care Homes were private limited companies owned by private investment and equity groups registered in tax havens such as Guernsey, Jersey, and the Cayman Islands. For example, Barchester Healthcare was a subsidiary of Grove Ltd, registered in the Bailiwick of Jersey where funds can be shifted from the nursing homes to chains with holding companies and subsidiaries in tax haven.30 Moreover, these large companies had shifted their financing from equity to debt funding where the interest payments are nontaxable and deducted before profits are taken.30

Costs

The revenues ranged from 55 million pounds at BUPA for its care homes although total BUPA revenues were 2.86 billion pounds in 2015–2016. Other chains reported revenues of 315 to 713 million pounds in 2015–2016. BUPA reported a loss of 1.2 million on its care homes and HC-One had a 3% profit (EBITDA) in 2015. The other 3 companies had 8% to 9% profits (EBITDA) and 15% to 20% EBITDAR profits in 2015.

Quality

Multiple concerns regarding the quality of care homes owned by corporate chains have arisen after scandals were widely reported by the media in Southern Cross’ facilities.31 Recently, the Care Quality Commission (2016) care home inspection reports found that 9% of homes provided inadequate care and 32% required improvement, and the Commission has received multiple allegations of abuse of the frail elderly.31,32,33 Unfortunately, the Commission’s quality reports were not available by owners and by chains.

Public accountability

Because the largest nursing homes are private companies (except for BUPA), there were no requirements to publish financial data, limiting financial transparency and accountability for government funds which pay about half of the revenues for care homes. Financial crises in local authority funding for nursing home care in the United Kingdom have been reported to be exacerbated by the policies that have safeguarded health care spending but not social care. This has resulted in large cuts in social spending over the 2010–2015 period.30,33 Government policy has not attempted to collect data on costs or quality nor to limit further growth and marketization of large care home chains.30

Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in the United States

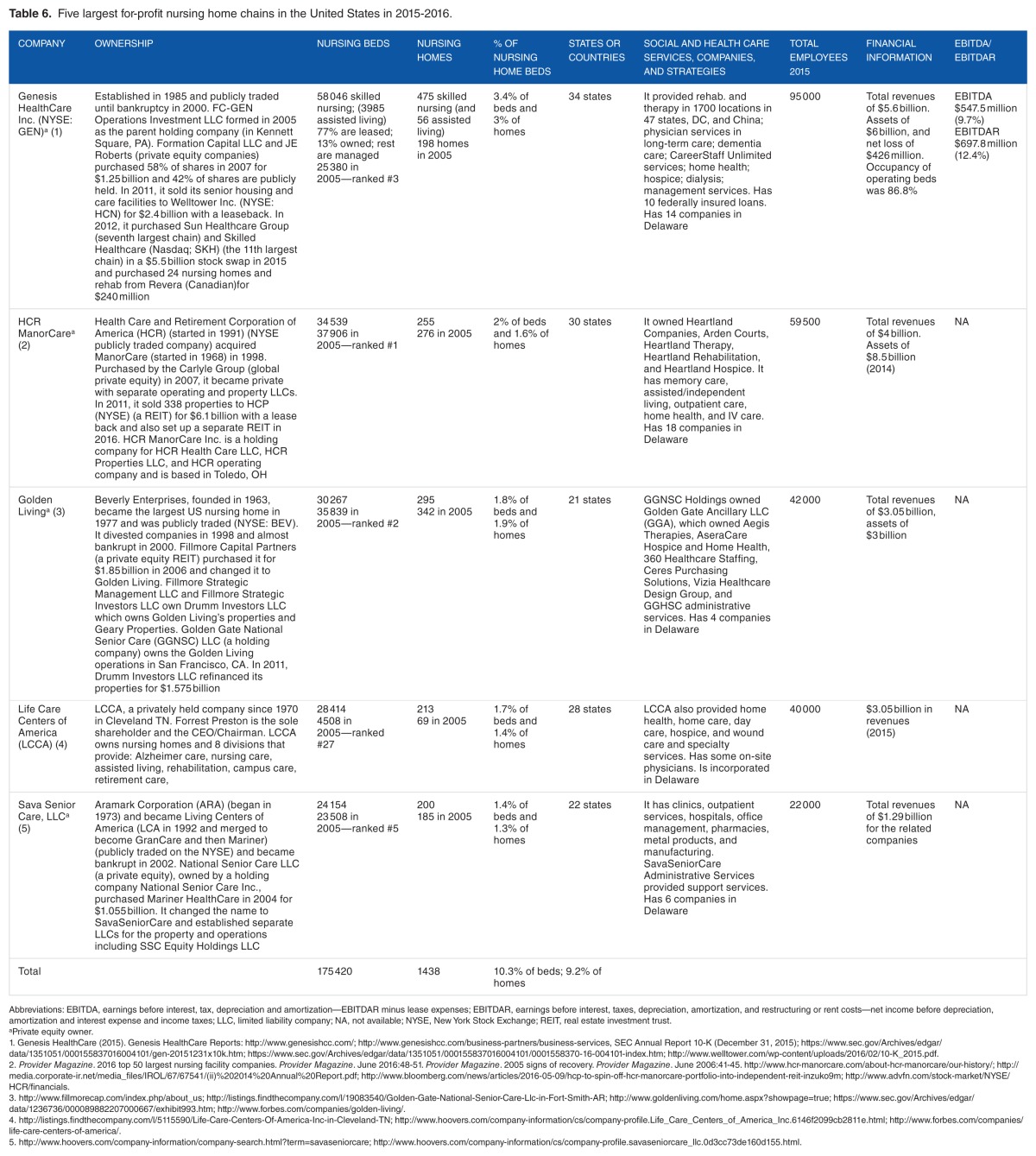

Ownership

In 2015, the 5 largest for-profit nursing home chains in terms of beds in the United States are shown in Table 6. Genesis HealthCare was the largest for-profit chain and the only 1 of 5 listed on the NYSE, although its controlling stock was owned by Formation Capital (a private equity company). The others were owned by private equity firms including the Carlyle Group, Fillmore Capital Partners, and National Senior Care Inc. Only Life Care Centers of America (LCCA) was privately owned by an individual.29 Over the decade, 4 of the 5 largest chains remained in the top 5 in 2015 although they changed positions, and Kindred was replaced by LCCA. Overall, the 5 largest for-profit chains had 10.3% of all nursing home beds and 9.2% of homes in 2015. The 4 of the 5 largest chains (except LCCA) had complex ownership structures with multiple owners, holding companies, and subsidiary companies.

Table 6.

Five largest for-profit nursing home chains in the United States in 2015–2016.

Corporate strategies

The 4 of the 5 large chains had moved their property ownership to either a separate REIT or a real estate company with leaseback arrangements. Their growth strategy was to acquire and merge with other nursing homes, and 3 chains showed a steady growth in beds and homes between 2005 and 2015–2016.

All the nursing home chains had diversified horizontally to include a full range of long-term care companies and services including assisted living, rehabilitation, home health, hospice, and other services. One chain established a physician group practice to care for long-term care patients and other businesses such as dialysis, whereas another offered on-site physician services. Three of the 5 chains provided management services to its own nursing homes as well as other nursing homes.

The 5 large chains had nursing homes in 21 to 34 states. Each of the 5 chains was incorporated in the state of Delaware, known as the most favorable US state in terms of taxes (a tax haven). Delaware allows companies to lower their taxes in another state by shifting royalties and similar revenues to holding companies in Delaware where they are not taxed.34

Costs

The 5 chains had large revenues ranging from $1.3 billion to $5.6 billion and 2015–2016. Because of the private ownership by 4 of the 5 companies, only Genesis had to publicly disclose its finances and its profits (EBITDAR of 12.4% in 2015–2016).

Quality

In recent years, all 5 of the largest chains had been charged with fraudulent practices by the US Department of Justice (USDOJ) and either had made large settlements with the government or had pending cases. In 2015, Genesis reached a settlement for failure to provide services ordered and recorded and a $52.7 million settlement for improper hospice billing and fraud and abuse in its therapy services, and it was under investigation for staffing and quality of care violations.35 HCR ManorCare was charged by the USDOJ for providing unreasonable and unnecessary services to government payers during 2006–2012.36 Golden Living was charged with filing false claims for hospice patients and reached a settlement for providing inadequate wound care in 2013.37 Life Care Centers of America settled a nationwide fraud case for filing of false claims for therapy services not medically reasonable and necessary (for $145 million with monitoring for 5 years).38 SavaSeniorCare LLC was also charged with false Medicare billing for unnecessary therapy.39

Using federal government data on nurse staffing and deficiencies for all US nursing homes, we examined the 5 largest for-profit chains in 2014. Registered nursing (RN) hours per resident day were significantly lower in Golden Living and SavaSeniorCare facilities than the national average. Total nursing hours were also significantly lower in 4 of the 5 chains compared with the national average. The 5 largest chains all had higher percentages of Medicare postacute patients than average so that these patients need more nursing and therapy hours than other patients. When staffing hours were adjusted for the percentage of Medicare patients, the actual RN hours were significantly lower than expected hours in 3 of the chains and total nursing hours were lower than expected in all 5 of the largest chains. With low staffing, it was not surprising that all the chains (except Golden Living) had significantly higher quality deficiencies than the national average during 2009–2014.

Public accountability

As noted above, only 1 of the largest chains had public reporting with annual reports available. Although government data on individual facility staffing and deficiencies were available for analysis for each chain, government reports on specific chain ownership, quality, and costs were not available.

Discussion

Despite similarities in the growth of elderly population in all 5 countries, the number of beds per 1000 over 65 has fallen in all countries. These trends and the low occupancy rates in the United Kingdom and the United States may indicate a preference for alternative services delivered in the home and in the community. High occupancy rates in Norway and Canada may indicate a lack of competition or a lack of alternative options for individuals.

Nursing homes owned or operated by chains were 64% in the United Kingdom (with a rapid growth in the last decade), 56% in the United States, and 17% in Sweden and Canada in 2014. In the context of the Scandinavian tradition of universal, tax-financed care services, centered on public provision, the recent wave of marketization, and the increasing role of for-profit companies in residential care for older people were unexpected. Sweden and Norway, however, with fairly similar welfare models were not affected to the same extent. In Norway, 5% nursing home beds were operated by for-profit chains compared with 17% in Sweden. Thus, the growth was considerable given that were no for-profit actors in Scandinavia before the beginning of the 1990s.1

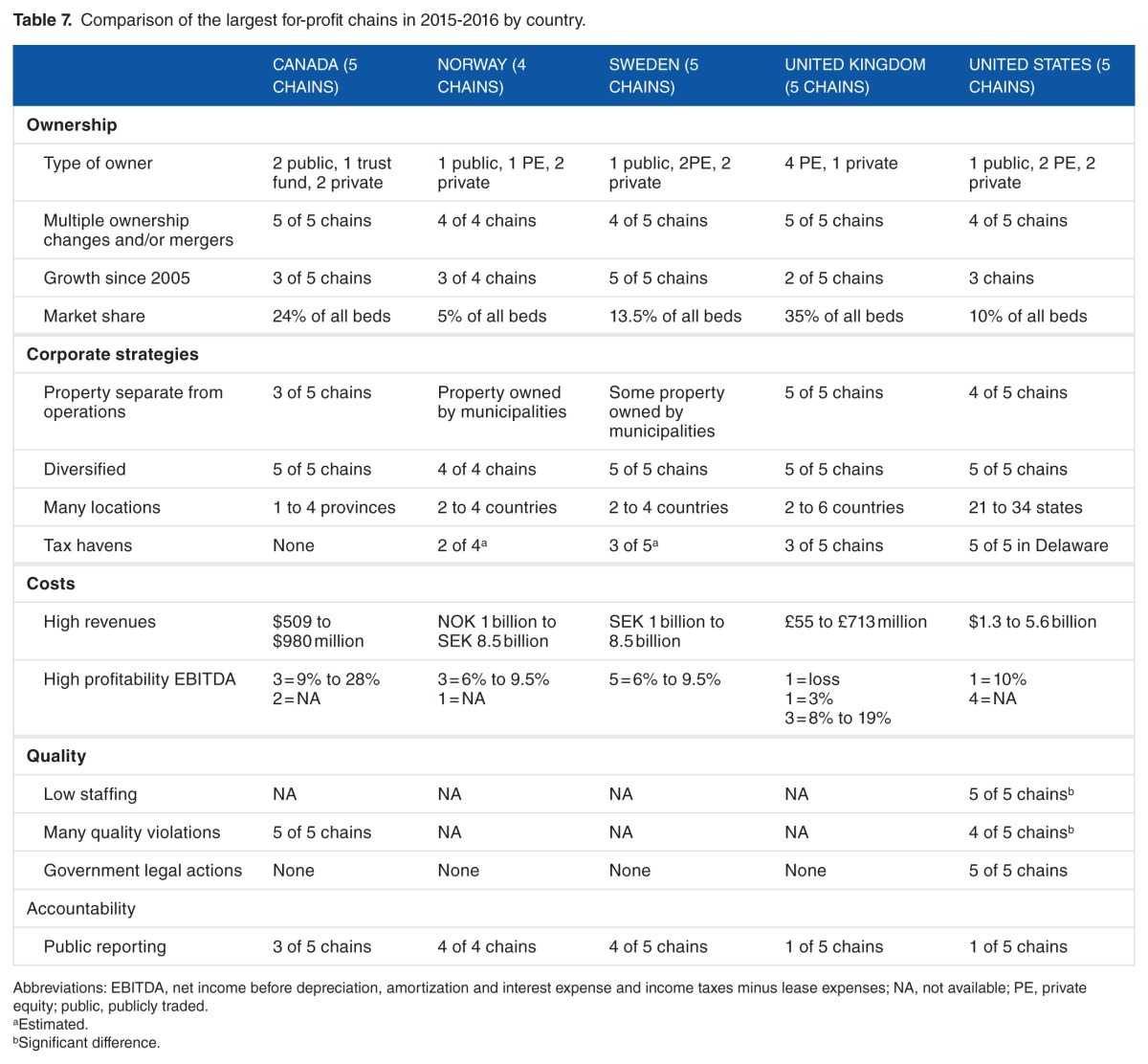

Ownership

Table 7 shows the comparisons for the key findings across the countries. In the 5 countries, the largest for-profit nursing home chains were primarily owned by private equity companies and investors. The exception was in Norway and Sweden where some private equity firms left the market. Overall, only a few for-profit chains were found to be publicly traded (2 in Canada, 1 in Norway and Sweden, none in the United Kingdom, and 1 in the United States). Some of the publicly traded companies also had private equity shareholders. Private equity companies are managed by partners in the funds for a fee or a percentage of the profits where capital gains made by the funds are not necessarily taxed. These companies are not required to publicly report on their financing and operations in contrast to publicly traded companies. There is a lack of clear ownership and financial transparency information on the large private companies in the 5 countries.

Table 7.

Comparison of the largest for-profit chains in 2015–2016 by country.

The largest for-profit nursing home chains generally had grown over the past decade by purchasing and/or merging with smaller companies that often involved a change of ownership and names (Table 7). The chains in this study showed a growing complexity of ownership patterns with many holding companies and subsidiaries.

The findings show that many nursing home chains have developed limited liability corporations (LLCs) or general or limited-partnership structures to limit the risk of financial loss to the amount invested. This is in contrast to partnerships or sole owners, where the owners are personally responsible for all business liabilities.30 As Burns et al30 has pointed out, where financial risks are limited, there is an incentive for corporate risk-taking. This was illustrated with the collapse of Carema in Sweden and Southern Cross in the United Kingdom.

Corporate strategies

Most of the large chains had separate legal entities for property companies or REITs and care operations (see Table 7). This is attractive to investors because the companies can be bought and sold separately.30 Taxes for property companies are generally lower than for other types of companies and interest rates on loans, and property rental rates can be artificially inflated to benefit the property owners.30,40 In addition, operating companies with few assets consider that they have protection from malpractice litigation and government sanctions particularly in the United States, but research is not available on this issue.41,42

Often the large REITs that specialize in nursing home chains use triple-net lease agreements that make individual nursing homes solely responsible for 3 types of costs: net real estate taxes on the leased assets, net building insurance, and net common area maintenance.30 These types of lease agreements have been problematic for some large chains as in the example of Southern Cross’ bankruptcy in the United Kingdom. Some chains have leases structured to include a proportion of the quarterly net income of the nursing home as a way of reducing taxes on profits and lowering the profit reports.40

The largest for-profit nursing home chains are often heavily debt financed by obtaining cash through loans from banks or investors consistent with previous studies in the United Kingdom and the United States.30,40 Interest payments are nontaxable and are deducted before profit is declared.30 In addition, Table 7 shows that many of the large nursing home chains used tax havens, which offered investors low or no taxes on profits (except for those chains in Canada).

The findings showed that almost every large for-profit chain across the 5 countries owned and operated a range of related long-term care companies (Table 7). This allows nursing home chains to purchase services from their own related companies to enhance profit taking. Using the practice of horizontal ownership, the chains are able to capture a full range of long-term care business to reduce market competition and improve corporate stability. A few large nursing home chains provided physician services to the clients across their long-term care network. Other large chains, particularly in Norway and Sweden, were found to be expanding into providing preschools as well as expanding into mental health, developmental disabilities, substance abuse, and refugee reception centers. Some companies reported a strategy to expand into the private pay market rather than relying on government payments for clients.

Some of the large chains in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States offered management services to their own nursing homes as well as other nursing homes. By creating separate management companies or services, the costs of management services can be charged to individual nursing homes at rates set by the parent company to offset its administrative costs.5–7 Nursing homes may have higher administration costs when they pay their parent companies for management services.41

Costs

Clearly, nursing home companies have been attractive to private investors because they often have high rates of return. Many of the large nursing home chains had revenues in the billions of dollars. With a few exceptions, the profits by the largest nursing home chains were high ranging from 6% to 28% across the 5 countries, despite financial market fluctuations (Table 7). The high profit margins were an expectation of private investors. One UK industry firm reported criticizing local governments because payment rates were not high enough to achieve the industry’s expected profit margins. As Burns and colleagues noted, this has resulted in an industry-supported narrative demanding greater government funding for nursing homes.43

Research has found that private equity companies often have higher operating and total income margins, as well as higher operating costs compared with other nursing home chains, but these may not be financially sustainable over the long term.30 A lack of stability in many chain owners and investors was found in this study by the frequent buying and selling of companies, nursing homes, and businesses in all 5 countries.

The profits of nursing home chains may be underreported and hidden in chain management fees, lease agreements, interest payments to owners, and purchases from related party companies.41 When owners take cash out of nursing homes by use of loans, fees, administrative costs, and other methods, the profitability margins of companies are hidden.30 Moreover, declared profits of chains and their operating subsidiaries can be manipulated over time to reduce taxes and pay dividends.30 Previous studies have found that government payers in the 5 countries have not established financial limits on administration and profits and have not required public financial transparency of administrative costs and profits by individual nursing homes or their corporate owners.44,45

Quality

Where data were available on quality, the large nursing home chains did not provide high-quality services. In Canada, for-profit homes had poorer quality of care than nonprofits and municipal homes based on violations (deficiencies) judged by government inspections (not significant).24–25 Four of the largest US chains also had significantly more quality violations than the average nursing homes and they all had charges of fraudulent billing practices pending or settled. The findings of higher deficiencies were consistent with previous studies of the poor quality of for-profit chains.6,11,41,46,47 The findings also showed scandals regarding quality of care in Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, as well as US government legal actions against 1 large Canadian chain and the 5 largest chains in the United States for poor-quality and fraudulent practices.

In the United States, the 5 largest nursing home chains provided significantly less registered nursing staff hours and total staffing than the level expected based on their resident acuity. The findings of low nurse staffing levels, especially RN staffing levels, in the largest US for-profit chains were consistent with previous studies in Canada, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States.26,28,48 Because nursing homes are labor-intensive, chains seeking high profit levels often reduce nurse staffing costs, especially RN costs, and cut wages, benefits, and pensions.30,31,49 As chains have become major providers of nursing home care, we conclude that countries need to focus greater attention on collecting and analyzing the quality of care and quality oversight of nursing home chains.

Public accountability

Overall, we found a lack of government information on the ownership, costs, and the quality of services provided by nursing home chains. Although Canada and the United States had quality data available on individual nursing homes that could be analyzed by chain, other countries did not have quality data available for nursing homes by owners and chains. When large nursing home chains can have such a major impact on the access, cost, and quality of nursing home residents, public accountability should be given a high priority by local, state, and country governments.

Policy and regulatory issues

As large nursing home chains and companies grow in dominance in the marketplace and political arena, countries have less control over the amount, type, and quality of nursing home and related long-term care services. Because of municipal ownership of nursing home properties, Norway is currently able to limit the growth of for-profit chains and control its contracts for nursing home services. As governments become more dependent on large nursing home chains for services, they are less able to terminate contracts, remove residents from poorly performing facilities, ensure that standards are maintained, and control the costs of care.

Governments should reconsider their policies of privatization of ownership in the context of increasing costs and quality problems. They should focus on the changing needs for ownership, financial, and quality reporting and oversight to address the challenges of privatization and marketization of nursing home and other long-term care services.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge support from the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Collaborative Research Initiative for the research initiative reimaging long-term residential care: An International Study of Promising Practices, Pat Armstrong, PI, York University, Toronto, Canada. The authors also would like to acknowledge William Hirst, Medical Student at Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK, for his research assistance.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW: Six peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 2510 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

CH, FFJ, JP, AP, SS, and MS planned the paper; contributed sections to the paper including the background, findings, tables, and the analysis of the findings; contributed to editing the paper; agree with the manuscript results and conclusions; and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. CH wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Disclosures and Ethics

The authors have confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality. There were no human and animal research subjects involved. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meagher G, Szebehely M. Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare: A Research Report on Legislation, Oversight, Extent and Consequences (Stockholm Studies in Social Work 30) Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comondore VR, Devereaux PJ, Zhou Q, et al. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillmer MP, Wodchis WP, Gill SS, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Nursing home profit status and quality of care: is there any evidence of an association? Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:139–166. doi: 10.1177/1077558704273769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronald LA, McGregor M, Harrington C, Pollock A, Lexchin J. Observational evidence of for-profit delivery and inferior care: when is there enough evidence for policy change? PLoS Med. 2016;13:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabowski DC, Feng Z, Hirth R, Rahman M, Mor V. Effect of nursing home ownership on the quality of post-acute care: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2013;32:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington C, Olney B, Carrillo H, Kang T. Nurse staffing and deficiencies in the largest for-profit nursing home chains and chains owned by private equity companies. Health Serv Res. 2013;47:106–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson D, Bramson JS, Grabowski DC. Nursing home ownership trends and their impacts on quality of care: a study using detailed ownership data from Texas. J Aging Soc Policy. 2013;25:30–47. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2012.705702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Neill C, Harrington C, Kitchener M, Saliba D. Quality of care in nursing homes: an analysis of relationships among profit, quality, and ownership. Med Care. 2003;41:1318–1330. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000100586.33970.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baum JAC. The rise of chain nursing homes in Ontario, 1971–1996. Soc Forces. 1999;78:543–583. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum JAC, Li SZ, Usher JM. Making the next move: how experiential and vicarious learning shape the locations of chains’ acquisitions. Admin Sci Quart. 2000;45:766–801. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banaszak-Holl J, Berta WB, Bowman D, Baum JAC, Mitchell W. The rise of human service chains: antecedents to acquisitions and their effects on the quality of care in US nursing homes, 1991–1997. Manage Decis Econ. 2002;23:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington C, Hauser C, Olney B, Rosenau PV. Ownership, financing, and management strategies of the ten largest for-profit nursing home chains in the US. Intern J Health Serv. 2011;41:725–746. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.4.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panos J. Crisis in care: Ontario pioneers the privatization of long term care. Briarpatch Magazine. Nov 1, 2011. https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/crisis-in-care.

- 14.Vabo M, Christensen K, Traetteberg HD, Jacobsen FF. Chapter 5. Marketization in Norwegian eldercare: Preconditions, trends and resistance. In: Meagher G, Szebehely M, editors. Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare: A Research Report on Legislation, Oversight, Extent and Consequences (Stockholm Studies in Social Work 30) Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlandsson S, Storm P, Stranz A, Szebehely M, Trydegard GB. Chapter 2. Marketizing trends in Swedish eldercare: competition, choice and calls for stricter regulation. In: Meagher G, Szebehely M, editors. Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare: A Research Report on Legislation, Oversight, Extent and Consequences (Stockholm Studies in Social Work 30) Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington C, Pollock AM. Decentralization and privatization of long-term care in UK and USA. Lancet. 1998;351:1805–1808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock AM. NHS Plc: The Privatization of Our Health Care. 2nd ed. London, England: Verso; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaffenberger KR. Nursing home ownership: an historical analysis. J Aging Soc Policy. 2000;12:35–48. doi: 10.1300/j031v12n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitchener M, Harrington C. The U.S. long-term care field: a dialectic analysis of institution dynamics. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;43:87–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . CASPER/OSCAR Federal On-Line Survey and Certification System Data Sets. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welltower . New York Stock Exchange. Annual 10-K report, 2015. New York, NY: 2016. http://www.welltower.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/10-K_2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Provider Magazine Top 50 largest nursing facilities companies. Provider Magazine. 2016 Jun;:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Justice . Extendicare Health Services Inc. agrees to pay $38 million to settle false claims act allegations relating to the provision of substandard nursing care and medically unnecessary rehabilitation therapy [press release] Washington, DC: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/extendicare-health-services-inc-agrees-pay-38-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations. Published October 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panos J. Care for sale: privatizing long-term care in Ontario; 4th International Conference on Evidence-based Policy in Long-Term Care, Invited Symposium Presentation; London, England: London School of Economics; Sep 5, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor MJ, Cohen M, Stocks-Rankin C-R, et al. Complaints in for-profit, non-profit and public nursing homes in two Canadian provinces. Open Med. 2011;5:183–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu AT, Berta W, Coyte PC, Laporte A. Staffing in Ontario’s long-term care homes: differences by profit status and chain ownership. Can J Aging. 2016;35:175–189. doi: 10.1017/S0714980816000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triton Ambea was acquired by Triton Fund III in March 2010 [press release] http://www.triton-partners.com/investments/private-equity/ambea/. Published 2010.

- 28.Arfwidsson J, Westerberg J. Profit Seeking and the Quality of Eldercare [Master thesis] Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm School of Economics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolt R, Jansson P. The Private Eldercare Market—Establishment, Development and Competition. Stockholm, Sweden: University of Stockholm; https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:196545/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Published 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns D, Cowie L, Earle J, et al. Where Does the Money Go? Financialised Chains and the Crisis in Residential Care. Manchester, UK: Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change (CRESC); Mar, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd L, Banerjee A, Harrington C, Jacobsen FF, Szebehely M. It is a scandal! Comparing the causes and consequences of nursing home media scandals in five countries. Intern J Social Soc Policy. 2014;34:2–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casalicchio E. Social care system failing workers—CQC chief inspector. Politics Home. Aug 9, 2015. https://www.politicshome.com/news/uk/health-and-care/news/68099/social-care-system-failing-workers-cqc-chief-inspector.

- 33.Burchardt T, Obolenskaya P, Vizard P. The Coalition’s record on adult social care: Policy, spending and outcomes 2010–2015. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics; London, UK: Jan, 2015. (Working Paper 17). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wayne L. How Delaware thrives as a corporate tax haven. New York Times. Jun 30, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/business/how-delaware-thrives-as-a-corporate-tax-haven.html.

- 35.US Department of Justice . Arlington nursing home agrees pay $600,000 to settle false Claim Act Violations [press release] Washington, DC: https://www.justice.gov/usao-edva/pr/arlington-nursing-home-agrees-pay-600000-settle-false-claim-act-violations. Published December 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Justice . Government sues skilled nursing chain HCR ManorCare for allegedly providing medically unnecessary therapy [press release] Washington, DC: https://www.justice.gov/usao-edva/pr/government-sues-skilled-nursing-chain-hcr-manorcare-allegedly-providing-medically. Published April 21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.US Department of Justice . Golden living agrees to pay over $600,000 to settle claims of inadequate care [press release] Washington, DC: 2013. https://www.fbi.gov/atlanta/press-releases/2013/golden-living-nursing-homes-settle-allegations-of-substandard-wound-care; http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-files-complaint-against-national-chain-hospice-providers-alleging-false-claims-medicare. [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Department of Justice . Life Care Centers of America Inc. Agrees to pay $145 million to resolve false claims act allegations relating to the provision of medically unnecessary rehabilitation therapy services [press release] Washington, DC: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/life-care-centers-america-inc-agrees-pay-145-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations. Published October 24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Justice . Government intervenes in lawsuits alleging that skilled nursing Chain SavaSeniorCare provided medically unnecessary therapy [press release] Washington, DC: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/government-intervenes-lawsuits-alleging-skilled-nursing-chain-savaseniorcare-provided. Published October 29, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradhan R, Weech-Maldonado R, Harman JS, Laberge A, Hyer K. Private equity ownership and nursing home financial performance. Health Care Management Rev. 2013;38:224–233. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31825729ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrington C, Ross L, Kang T. Hidden owners, hidden profits, and poor nursing home care: a case study. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45:779–800. doi: 10.1177/0020731415594772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevenson D, Grabowski D. Private equity investment and nursing home care: is it a big deal? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:1399–1408. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaingBuisson . Fair Price for Care: Calculating a Fair Price for Nursing and Residential Care for Older People and People With Dementia October 2014- September 15. 6th ed. London, England: 2015. http://www.laingbuisson.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrington C, Ross L, Mukamel D, Rosenau P. Improving the Financial Accountability of Nursing Facilities. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrington C, Armstrong H, Halladay M, et al. Nursing home financial transparency and accountability in four locations. Ageing Int. 2016;41:17–39. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grabowski DC, Hirth RA, Intrator O, et al. Low-quality nursing homes were more likely than other nursing homes to be bought or sold by chains in 1993–2010. Health Aff. 2016;35:907–914. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Government Accountability Office . CMS’s Specific Focus Facility Methodology Should Better Target the Most Poorly Performing Facilities Which Tend to Be Chain Affiliated and for-Profit (GAO-09-689) Washington, DC: GAO; Aug, 2009. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09689.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrington C, Schnelle JF, McGregor M, Simmons SF. The need for minimum staffing standards in nursing homes. Health Serv Insight. 2016;9:13–19. doi: 10.4137/HSI.S38994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrington C, Stockton J, Hoopers S. The effects of regulation and litigation on a large for-profit nursing home chain. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2014;39:781–809. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2743039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System (CANSIM) Tables 051-0001, 107-5502, 107-5501, 107-5509, 107-5512, 107-5502, 107-5512. Ottawa, Ontario: 2016. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/subject-sujet/theme-theme.action?pid=40000&lang=eng&more=0&MM. Accessed December 2016. Excludes Quebec. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canadian Institute for Health Information 2014 . Health Spending on Nursing Homes 2013 Residential Long-term Care Financial Data Tables 2013. Ottawa, ON: CIHI (in Canadian dollars); 2006. https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2740 and Chartwell Senior Housing REIT Annual Information Form. [Google Scholar]

- 52.UK Office of National Statistics . Population Estimates for UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Island. Newport; NSW: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Statistics Norway . Nursing and Care Services. Oslo, Norway: Jul, 2014. (in Norwegian Kroner). Nursing and Care Services. July 2014 (in Norwegian Kroner) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Statistics Sweden . 2016 Database, Population by Age, Sex and Year. Stockholm, Sweden: 2016. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/?rxid=5ac9ea98-5967-477e-9db3-a8de0f7c4f88. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergman M, Jordahl H. (Ministry of Finance, ESO-Report).Goda år på ålderns höst? 2014;1:29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Socialstyrelsen . Vård och omsorg om äldre—lägesrapport 2007. 2007. p. 20.p. 24.p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Socialstyrelsen . Statistics on Elderly and Persons with Impairments—Management Form 2015. 2016. Table 10. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swedish statistics only differentiate between public and private provision. The proportion provided by chains has been calculated by the authors.

- 59.Socialstyelsen . Vård och omsorg om äldre—lägesrapport 2015. 2016. p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Socialstyrelsen . Avgifter inom äldreomsorgen. 2014. p. 32. All nursing home residents are subsidized by public monies. [Google Scholar]

- 61.LaingBuisson . Care of Older People UK Market Report. 27th ed. London, England: LaingBuisson; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 62.LaingBuisson . Care of Elderly People, UK Market Survey 2009. London, England: LaingBuisson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Care Quality Commission (CQC) Data for care homes. Newcastle: CQC; Independent Regulator of Health and Social Care in England. http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/care-homes. Accessed November 22, 2016. Includes nursing homes and dual registered homes, data for local authority nursing beds/homes unknown but estimated <500 beds, excludes National Health Service (NHS) facilities but includes long-term NHS beds for geriatrics. Chains are defined as private companies, individuals/partnerships with 3 or more homes or any listed company. [Google Scholar]

- 64.US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015 Edition. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harrington C, Carrillo C, Dowell M, Tang PP, Blank BW. Nursing Facilities, Staffing, Residents and Facility Deficiencies, 2005–2010. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrington C, Carrillo H, Garfield R. Nursing Facilities, Staffing, Residents and Facility Deficiencies, 2009 Through 2014. Aug, 2015. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. [Google Scholar]

- 67.US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . National Health Expenditure Data Historical. Baltimore: MD: 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Extendicare Annual Report. 2005–2016. https://www.extendicare.com/investors/about-extendicare/

- 69.Revera . Revera expends investment agreement with health care REIT to share ownership of 23 retirement communities across Canada. News Release April 2, 2015. CBRE. Revera completes divestiture of United States skill nursing centers to Genesis HealthCare; Dec 1, 2015. http://www.reveraliving.com/; http://www.investpsp.com/pdf/info-source-revera-en.pdf; http://www.investpsp.com/pdf/PSP-AR-2016-complete.pdf; http://www.welltower.com/about-us/welltowers-history/; http://www.welltower.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/10-K_2015.pdf; Retirement REIT. Annual Information Report 2006; 4. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sienna Senior Living Management Discussion & Analysis. 2016. http://www.siennaliving.ca/; http://www.sedar.com/CheckCode.do; Leisureworld from Macquarie Power & Infrastructure Income Fund, Annual Information Form; 2005:3.

- 71.Chartwell Management’s Discussion & Analysis. http://chartwell.com/index; June 30, 2016. http://investors.chartwell.com/Cache/1001207528.PDF?Y=&O=PDF&D=&fid=1001207528&T=&iid=4100072. Chartwell, Annual Information Report; 2006:16.

- 72.Schlegel Villages http://schlegelvillages.com/about-us; http://www.rbjschlegel.com/. Data for 2005 from 2011 Web site: https://web.archive.org/web/20110315072657/; http://www.schlegelvillages.com/about-us. BRE (2015) Seniors Housing & Healthcare; 2015. Market Outlook, February 10.