Abstract

My great-grandfather, Rodger Cantwell, and his family managed to survive the Irish famine that began in 1845. Blending what family records we have with Kelly's outstanding 2012 book about the era, the following is an historical fictional account of Rodger's saga.

When the potato famine swept through Ireland in 1846, I was 30 and my wife, Mary (McDonald), 33. We lived in a small cabin valued at only 5 shillings, where I was one of 30 farm laborers on the estate of George Fawcett, Esq. in Toomyvara, Tipperary. At that time we had five children: Bridget (age 8), Thomas (7), Michael (4), Julia (2), and little Mary (1). Because of a generation-long collapse in our living standards, we came to rely mainly on potato farming for our sustenance. A single acre of potatoes could yield up to 6 tons of food, enough to feed our family for the year.

It had been raining a lot, even more than usual for Ireland. In October 1845, almost overnight, a dense blue fog settled over our puddled potato fields. An odor of decay permeated the air. When the wind and rain died away, there was a terrible stillness. The potato crop was ruined, destroyed (we learned later) by the fungus Phytophthora infestans.

Over especially the next 2 years, life was miserable. We were always hungry and lost weight. England gave us some Indian corn and maize, but it was poorly ground and caused abdominal pain and diarrhea.

In an effort to earn some money, I joined a public works labor force, sponsored by the British, building roads and digging ditches that seemed to have little purpose. It did pay 10 pence per day (12 pence equals 1 shilling), almost double my salary as a potato farmer. By August 1846, many of my countrymen had joined me in this endeavor, as the labor force increased fivefold to 560,000.

We tried planting potatoes again in 1846, but stalks and leaves of the potatoes were blackened, accompanied by a sickening stench, and within only 3 to 4 days the whole crop was obliterated.

Our family was very fortunate, somehow avoiding the pestilence (typhus, relapsing fever, dysentery, and scurvy) that many of our neighbors succumbed to. We narrowly avoided having to go to one of the area workhouses. The Irish Poor Land System resulted in building 130 such workhouses, with a total of 100,000 beds, but the British goal was bizarre: they wanted to make poverty so unendurable that we (its victims) would embrace the virtue of the “saved,” namely to be more industrious, self-reliant, and disciplined. Hard to do, I'd say, when one is starving and out of work.

Many of the British took the attitude that the famine was God's punishment toward a sinful people. We Catholics (80% of our population but not in ruling authority like the Protestants) didn't agree with this nonsense.

Despite the fact that many of us were starving, our country kept having to export foods to England—oats, bacon, eggs, butter, lard, pork, beef, and fresh salmon. In return, Britain did open up soup kitchens for us, but of 2000 planned, only half were in operation in 1847.

In 1847, I was able to do some work again in the potato fields, as the crop was finally healthy but only one-fourth normal size, as we had to eat the seed potatoes and grain over the past winter to stay alive.

That year Britain passed its Extended Poor Law, shifting the cost of feeding the starving masses and the maintenance of poorhouses to the Irish landowner. This, in effect, made eviction of tenant farmers (like I was) an efficient way for the landowner to lower his tax (poor rate). Between 1847 and 1851, the eviction rate rose nearly 1000%.

We held on until June 1849, when George Fawcett, Esq. hired agent Richard Wilson to bring in a crew of men overnight and destroy all of the little cabins his 30 tenants lived in (Figure 1). He did offer to pay our passage via ship, first to Liverpool and eventually to New York. Big of him.

Figure 1.

An example of destroyed Irish cottages like ours. Source: Kelly, 2012 (1).

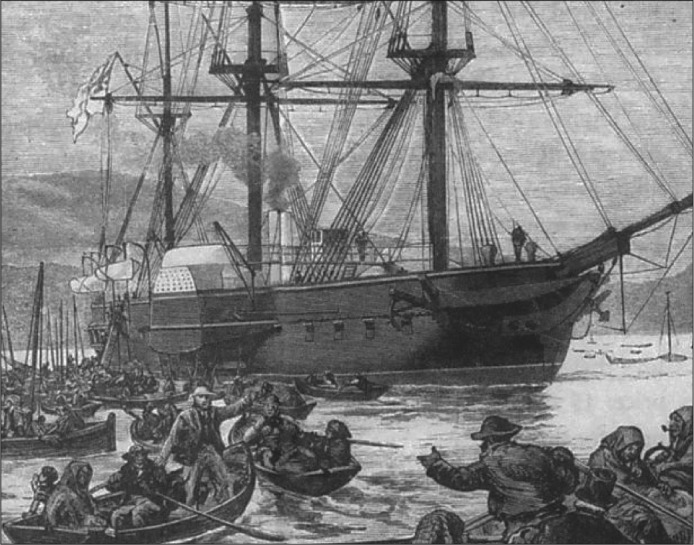

Our family survived, in temporary shelters, until April 19, 1850, when I put Bridget (12), Thomas (10), Patrick (8), and Mary (7) on the boat Princeton with several relatives (Figure 2). The trip took 2 months. Fortunately, living conditions on board had improved since the crowded trips 3 to 4 years earlier, when 30% or more died en route. I left Liverpool 6 months later on the Waterton.

Figure 2.

Example of the ship we took to sail to America. Source: Kelly, 2012 (1).

October 30, 1850. We managed to avoid the “runners” and bullies who preyed upon the new arrivals and settled in Rochester, NY, where our daughter, Jennie, was born in 1856. We came by boat to Milwaukee that same year, where our youngest son, William, was born in 1858 and where I worked as a common laborer until my death from a heart attack at age 55, in 1870 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The author at his great-grandfather's grave in Milwaukee.

My widow, Mary, then moved to Shawano, Wisconsin, with daughter Jennie (14) and William (11), where married daughter Mary was living with her husband Cornelius. Wife Mary died at 76 in Shawano. Her physician was her youngest son, William, who had graduated from Rush Medical School in Chicago the year before.

As I reflect back upon my life, and those who have come after me, I believe we are of hardy stock to have survived such difficult times, including the famine, febrile illnesses, and hazardous boat trips. So many of our friends and neighbors weren't as fortunate. Our seven children lived to fairly old ages (80, 79, 79, 77, 74, 60), except for little Mary, who died of an infection at 33, long before antibiotics became available. I am especially proud that even though I came from humble means, every generation since, beginning with youngest son William, has had physicians (six to date, over four generations) and other fine occupations. None became farmers, like I was, although grandson Arthur dabbled in it. (He proved to be a much more successful obstetrician than farmer.) Fortunately, my great-grandson John chose cardiology over farming, since he once poured gas in the radiator of a tractor and almost drove off an incline going into the barn.

The British have had moments of greatness through the years, none more so than their heroic actions at the outset of World War II. However, their leaders like the Whig Charles Trevelyan came up far short during our famine years. As historian John Kelly wrote in 2012:

The relief policies that England employed during the famine—parsimonious, short-sighted, grotesquely twisted by religion and ideology—produced tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of needless deaths (1).

Our population of 8.2 million was reduced by one-third between 1845 and 1855. Over 1 million died of starvation and disease, while another 2 million emigrated to other countries.

One of the worst policies was the Extended Poor Law of 1847, which eventually resulted in the destruction of our little home and eviction of our family. However, if not for this, our family might still be living in Ireland instead of America.

The bad feelings toward the British persisted for several generations. My youngest son, William, the first family physician (and the first family member to leave the Catholic Church), once said that if he thought he had even a drop of English blood in his body he'd cut his finger and let the drop drip out. He had to be careful where he expressed this, for his wife Harriet's grandparents had come from Foville (Wiltshire) England, leaving for America in 1830, well before the famine years.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to my sister, Sally Cantwell Basting, for her diligent research into our family's Irish roots.

References

- 1.Kelly J. The Graves Are Walking. New York: Henry Holt & Co; 2012. [Google Scholar]