Abstract

Background

Psychosocial interventions can improve eating behaviours and psychosocial functioning in bariatric surgery candidates. However, those that involve face-to-face sessions are problematic for individuals with severe obesity due to mobility issues and practical barriers.

Objective

To examine the efficacy of a pre-operative telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy (Tele-CBT) intervention versus standard pre-operative care for improving eating psychopathology and psychosocial functioning.

Methods

Preoperative bariatric surgery patients (N = 47) were randomly assigned to receive standard preoperative care (n = 24) or 6 sessions of Tele-CBT (n = 23).

Results

Retention was 74.5% at post-intervention. Intent-to-treat analyses indicated that the Tele-CBT group reported significant improvements on the Binge Eating Scale (BES), t (22) = 2.81, p = .01, Emotional Eating Scale (EES), t (22) = 3.44, p = .002, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), t (22) = 2.71, p = .01, whereas the standard care control group actually reported significant increases on the EES, t (23) = 4.86, p < .001, PHQ-9, t (23) = 2.75, p = .01, and General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), t (23) = 2.93, p = .008 over the same time period.

Conclusions

Tele-CBT holds promise as a brief intervention for improving eating psychopathology and depression in bariatric surgery candidates.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioural therapy, Telephone therapy, Bariatric surgery, Gastric bypass, Obesity

Major clinical guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for individuals with extreme obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) exceeding 40 kg/m2, and for individuals with a BMI exceeding 35 kg/m2 if there are significant obesity-related comorbidities (Mechanick et al., 2013; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006). Bariatric surgery restricts the amount of food an individual is able to consume at one time and can be conceptualized as a forced behavioural modification program. Gastric bypass bariatric surgery is very effective in reducing weight in the short-term, with maximum weight change typically occurring in the first year post-surgery; however, weight change trajectories are highly variable (Courcoulas et al., 2013). Approximately 50% of patients experience some weight regain by 2 years post-surgery (Magro et al., 2008). In 24% of patients, the extent of weight regain is considerable relative to their overall weight loss at 3 years post-surgery (Courcoulas et al., 2013).

One potential explanation for the variability in post-operative outcomes is that surgery alone does not directly address the psychological factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of obesity, including counterproductive cognitions (e.g., self-defeating or self-sabotaging thoughts) and negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety, anger) that lead to maladaptive eating behaviours. High rates of psychiatric comorbidity have been documented in bariatric surgery candidates including mood, anxiety, and eating disorders (Muhlhans, Horbach, & De Zwaan, 2009). Although the impact of pre-operative psychiatric disorders and various forms of disordered eating on post-operative weight loss is currently inconclusive (Livhits et al., 2012), post-operative binge eating, loss of control eating, uncontrolled eating/grazing, and depression have been shown to negatively impact weight loss outcomes, and adherence to dietary guidelines has been shown to positively impact weight loss outcomes (Meany, Conceicao, & Mitchell, 2014; Sheets et al., 2015).

In light of these issues, adjunctive psychosocial interventions are increasingly being recommended in the clinical management of bariatric patients (Beck, Johannsen, Stoving, Mehlsen, & Zachariae, 2012; Kalarchian & Marcus, 2015; Meany et al., 2014; Sheets et al., 2015). However, psychosocial interventions are not yet routinely offered in most bariatric surgery programs, in part because no “best practices” have been established. A search of the empirical literature suggests that the most common forms of psychosocial interventions include multi-component behavioural lifestyle interventions and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions. Behavioural lifestyle interventions typically include components such as dietary advice, physical activity, food monitoring, and stimulus control. CBT interventions include many behavioural interventions, but also incorporate cognitive strategies (e.g., identifying, challenging, and altering counterproductive thoughts).

Most of the empirical studies conducted to date have examined the impact of post-operative psychosocial interventions on outcomes such as diet, physical activity, disordered eating, psychosocial functioning, and weight loss (for reviews, see Beck et al., 2012; Kalarchian & Marcus, 2015; Rudolph & Hilbert, 2013). In comparison, fewer studies have examined the effectiveness of pre-operative psychosocial interventions; however, preliminary evidence suggests that bariatric candidates may benefit from acquiring coping skills prior to surgery in order to help them prepare for surgery and adjust following surgery. Uncontrolled studies suggest that pre-operative CBT is feasible and potentially useful in helping bariatric surgery candidates improve their eating behaviours (Ashton, Drerup, Windover, & Heinberg, 2009) and lose more weight following surgery (Ashton, Heinberg, Windover, & Merrell, 2011). A prospective observational study that followed 30 patients for two years found that those who had received 12 sessions of pre-operative CBT were far more likely to have lost over 50% of their excess weight following surgery (94% vs. 12%) (Abiles et al., 2013). A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) reported that a 6 session pre-operative CBT intervention was efficacious in increasing objectively measured physical activity (Bond et al., 2015), and another RCT reported that a 10 session CBT intervention was efficacious in improving eating behaviours, depression, and anxiety during the pre-operative period relative to standard care, but did not confer additional benefits beyond surgery at the 1 year follow-up (Gade, Friborg, Rosenvinge, Småstuen, & Hjelmesæth, 2015).

Previous research interventions have employed almost exclusively face-to-face treatments, although some studies have incorporated the use of telephone sessions (Gade et al., 2015; Kalarchian et al., 2012). Travelling for appointments poses practical barriers (e.g., missing work, childcare issues), and is even more difficult for bariatric patients due to mobility challenges secondary to obesity (King et al., 2012). Few patients live in close proximity to bariatric surgery programs, and travel distance is inversely associated with attendance at appointments (Lara et al., 2005), further reinforcing the need for psychosocial treatment modalities that can overcome this barrier. Telephone-based CBT (Tele-CBT) has previously been utilized in medical populations by adapting standard CBT manuals (Mohr et al., 2000); however, no published studies have examined the efficacy of Tele-CBT in a bariatric surgery population.

Our team developed a CBT manual for bariatric surgery patients adapted to delivery by telephone (Cassin et al., 2013). The objective of the current pilot RCT was to compare the efficacy of a pre-operative Tele-CBT intervention (Tele-CBT) to standard pre-operative bariatric care (Control) in improving eating psychopathology (primary outcome) and psychosocial functioning (secondary outcome). Specifically, it was hypothesized that the Tele-CBT group would report significant improvements in eating psychopathology, depression, anxiety, and quality of life immediately following the intervention, and that their scores would improve to a greater extent than the standard care control group.

1. Methods

1.1. Participants

Participants (N = 72) were adult bariatric surgery candidates recruited from a Canadian Bariatric Surgery Program. Exclusion criteria included current ineligibility for bariatric surgery, lack of computer access, or having significant language barriers, poorly controlled psychiatric illness or severe medical illness that would render Tele-CBT very difficult. Given the absence of clear pre-operative psychological predictors of bariatric surgery outcome (Livhits et al., 2012), participation was not limited to bariatric candidates with clinically significant eating psychopathology (e.g., binge eating) or general psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety). The intervention focused on the development of adaptive coping skills that are thought to be helpful for all patients in adhering to dietary guidelines (see description of Tele-CBT protocol below).

1.2. Design

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Board, and the trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01508585). Patients were informed about the study by a dietician, social worker, or research coordinator during the pre-surgical assessment process. The pre-surgical assessment process includes a psychodiagnostic assessment conducted by a psychologist or psychiatrist (see Sockalingam et al. (2013) for more information about the presurgical assessment process and exclusion criteria for surgery). Patients who were determined to be eligible for surgery and who were interested in learning more about the study provided their contact information. After completing informed consent and a phone screen to determine eligibility, participants were e-mailed a link to the online questionnaire packet administered through Survey Monkey ™. Participants were randomly assigned using a computer generated random sequence to either the Tele-CBT group or Control group at an allocation ratio of 1:1, and a research coordinator notified them of their group assignment upon completion of the questionnaire packet. Participants assigned to the Tele-CBT group were scheduled their first session approximately one week after completing their baseline questionnaire packet. On average, the first Tele-CBT session occurred 4.7 months prior to bariatric surgery. Those in the control condition received standard bariatric care. The time interval between the pre- and post-measures was 7 weeks.

1.3. Telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy

The six Tele-CBT sessions were each approximately 55-min in duration and scheduled weekly at a time convenient for the participants. Two Master-level psychometrists experienced in the assessment and treatment of bariatric surgery patients conducted the sessions. They received training on the Tele-CBT protocol and worked under the supervision of two doctoral level registered clinical psychologists (SC and SW).

The development of the Tele-CBT protocol and the content of the sessions, as well as preliminary evidence for the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of the protocol, have been previously described elsewhere (Cassin et al., 2013). Briefly, the Tele-CBT sessions focused on introducing the cognitive behavioural model of overeating and obesity, scheduling healthy meals and snacks at regular time intervals and recording consumption using food records, scheduling pleasurable alternative activities to overeating, identifying and planning for difficult eating scenarios, reducing vulnerability to overeating by solving problems and challenging negative thoughts, and preparing for bariatric surgery. Participants were expected to complete CBT homework between sessions, such as completing food records, engaging in pleasurable and self-care activities, and completing a variety of worksheets (e.g., thought records, problem-solving worksheets).

1.4. Standard bariatric care

Participants assigned to the control group attended routine pre-operative clinic visits and received the standard of pre-operative care. These visits included standard pre-operative assessments, education on bariatric surgery and nutrition, and access to an optional monthly support group (Pitzul et al., 2014).

1.5. Measures

Eating psychopathology was assessed using the Binge Eating Scale (BES; Gormally, Black, Daston, & Rardin, 1982) and Emotional Eating Scale (EES; Arnow, Kenardy, & Agras, 1995). The BES is a 16-item self-report measure designed specifically for use with individuals with obesity that assesses binge eating behaviours (e.g., amount of food consumed) as well as associated cognitions and emotions (e.g., guilt, shame). The EES is a 25-item self-report measure that assesses the tendency to cope with negative affect by eating. Respondents are presented with 25 emotions and are asked to rate the strength of their urge to eat on a scale from 0 (no desire to eat) to 4 (an overwhelming urge to eat) when experiencing each of the emotions. The EES consists of 3 subscales reflecting eating in response to anger/frustration, anxiety, and depression.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & The Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group, 1999), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006), and Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36; Ware, Kosinski, & Kelle, 1994). The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure of depression severity. Respondents are asked to rate the frequency with which they have experienced depressive symptoms over the last two weeks on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 9 (nearly every day). The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report measure of anxiety severity. It was originally developed to diagnose generalized anxiety disorder, but it has also proved to be a good screening instrument for other disorders including panic disorder, social phobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006). Respondents are asked to rate the frequency with which they have experienced anxiety symptoms over the last two weeks on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 9 (nearly every day). The SF-36 is a 36-item self-report measure of health-related quality of life. The SF-36 covers the domains of physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. These domains are summarized into a Physical Health Summary Score and a Mental Health Summary Score.

2. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 18.0; SPSS, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and frequency counts were calculated to describe participant characteristics. Independent t tests and chi-square were used to compare completers with dropouts, and to compare the Tele-CBT group with the Control group, on demographic variables and baseline clinical variables.

A 2 (Group: Tele-CBT vs. Control) × 2 (Time: baseline, post-intervention) mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed separately for each outcome variable to examine significant changes in eating psychopathology, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Cohen’s d effect size (.2 = small effect, .5 = medium effect, .8 = large effect) was computed from the F-test. Significant Group × Time interactions were followed up with paired-samples t-tests to examine significant changes over time separately for each group. Data analyses were first conducted with study completers (n = 35), and then intent-to-treat analyses (last observation carried forward) were conducted with all participants (N = 47). Although the effect sizes were greater in the completer analysis, the pattern of significant results was identical across both analyses. The results reported below are for the intent-to-treat analyses.

3. Results

Recruitment and Participant Flow

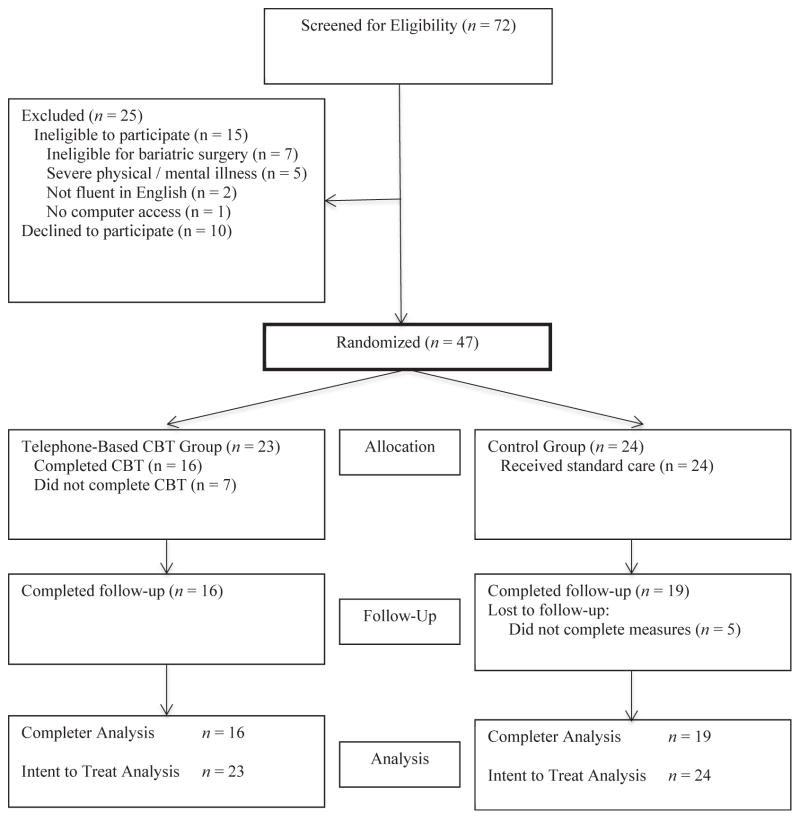

The CONSORT diagram is depicted in Fig. 1. Recruitment for the study occurred over a period of 9 months. Of 72 individuals screened for eligibility, 15 did not meet the study inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 10 chose to not participate. Of the remaining 47 participants who were randomly assigned to the Tele-CBT group (n = 23) or Control group (n = 24), 35 (74.5%) completed the post-treatment measures: 16 (70.0%) from the Tele-CBT Group and 19 (79.1%) from the control group. Of the 7 individuals who discontinued Tele-CBT, 3 (42.9%) cited time constraints (i.e., family/work commitments), 1 (14.3%) cited lack of privacy for phone calls, and 3 (42.9%) did not provide a reason (i.e., did not respond to phone calls or e-mails). Study completers had lower physical quality of life than study dropouts at baseline; however, they did not differ from one another on any other baseline clinical variables or demographic variables.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram of participant flow.

Participant Characteristics

Participants (n = 47) had a mean age of 45.5 years (SD = 8.9), and the sample was predominantly female (n = 39; 83.0%) and White (n = 43; 91.5%). In terms of marital status, 30 (63.8%) were married or cohabiting, 11 (23.4%) had never been married, 4 (8.5%) were separated or divorced, and 2 (4.3%) were widowed. Participants were generally quite well educated: 23 (48.9%) had completed a college or university degree, and 15 (31.9%) completed some college or university courses. Participants had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 53.1 kg/m2 (SD = 12.0). The Tele-CBT group and Control group did not differ with respect to any demographic variables or baseline clinical variables.

Effect of the Intervention

Changes in eating psychopathology, depression, anxiety, and quality of life are reported in Table 1. The Group × Time interaction was significant for the BES, EES, PHQ-9, and GAD-7. Follow-up paired-samples t-tests indicated that the Tele-CBT group reported significant improvements on the BES, t (22) = 2.81, p = .01, EES, t (22) = 3.44, p = .002, and PHQ-9, t (22) = 2.71, p = .01, as well as a trend for improvement on the GAD-7, t (22) = 1.85, p = .08. In contrast, the Control group actually reported significant increases on the EES, t (23) = 4.86, p < .001, PHQ-9, t (23) = 2.75, p = .01, and GAD-7, t (23) = 2.93, p = .008, as well as a trend for increase on the BES, t (23) = 1.82, p = .08, over the same time period.

Table 1.

Comparison of telephone-based CBT (N = 23) and standard bariatric care control (N = 24) groups at baseline and immediately following the intervention.

| Variable | Baseline

|

Post-intervention

|

F (1,45)a | db | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control

|

Tele-CBT

|

Control

|

Tele-CBT

|

|||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| BES | 15.7 (7.5) | 11.6 (8.8) | 16.1 (7.5) | 8.7 (8.0) | 9.74** | 0.93 |

| EES-Anger | 18.5 (8.9) | 18.1 (9.2) | 18.8 (9.0) | 15.2 (7.4) | 12.14*** | 1.04 |

| EES-Anxiety | 14.6 (6.3) | 14.9 (7.5) | 14.9 (6.2) | 12.1 (4.3) | 8.24** | 0.86 |

| EES-Depression | 10.0 (4.4) | 9.7 (4.4) | 10.2 (4.6) | 8.0 (3.9) | 12.44*** | 1.05 |

| PHQ-9 | 5.2 (4.8) | 5.0 (4.5) | 6.4 (5.3) | 3.3 (3.4) | 14.17*** | 1.12 |

| GAD-7 | 3.9 (3.7) | 2.5 (2.9) | 5.1 (3.9) | 2.0 (3.1) | 12.00*** | 1.03 |

| SF-36 Physical | 38.0 (9.2) | 32.7 (12.0) | 38.1 (9.1) | 35.5 (10.9) | 3.41 | 0.55 |

| SF-36 Mental | 52.1 (9.2) | 55.1 (9.3) | 51.9 (9.2) | 56.4 (8.3) | 1.15 | 0.32 |

Note. BES = Binge Eating Scale; EES = Emotional Eating Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire (9 item); GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder (7 item); SF-36 = Short-Form (36) Health Survey.

The F-statistic is for the Group (Tele-CBT vs. Control) × Time (baseline vs. post-intervention) interaction.

Effect sizes were computed from the F-tests. d = Cohen’s effect size (.2 = small effect, .5 = medium effect, .8 = large effect).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

4. Discussion

The current pilot RCT found Tele-CBT to be a feasible intervention and efficacious in improving eating psychopathology and psychosocial functioning in pre-operative bariatric surgery patients. These findings are in line with previous research that has found CBT to be effective in improving disordered eating and affective symptoms in pre-operative bariatric surgery patients (Ashton et al., 2009; Gade et al., 2015). The RCT design of the current study permitted comparison with a standard pre-operative bariatric care control group. As hypothesized, the Tele-CBT group improved to a greater extent than the control group on all of the aforementioned variables, with large effect sizes (ranging 0.86 to 1.12 in intent-to-treat analyses). Interestingly, the control group actually experienced an increase in eating psychopathology, depression, and anxiety over the same time frame. Taken together, the findings of this pilot RCT suggest that CBT holds promise as a brief intervention for bariatric surgery candidates awaiting surgery.

Bariatric surgery patients experience many physical and practical barriers that limit their access to psychological treatment. Given that few patients live in close proximity to Bariatric Centres of Excellence (Lara et al., 2005), it is important to investigate novel methods of treatment delivery that have the potential to reach a greater number of patients (Kalarchian & Marcus, 2015). Previous research has found Tele-CBT to have levels of treatment satisfaction comparable to face-to-face CBT (Tutty, Ludman, & Simon, 2005), and to be efficacious in treating various forms of psychopathology that are prevalent among bariatric surgery patients, including binge eating (Wells, Garvin, Dohm, & Striegel-Moore, 1997) and depression (Ludman, Simon, Tutty, & Von Korff, 2007; Mohr et al., 2005; Tutty, Sprangler, Poppleton, Ludman, & Simon, 2010). A few intervention studies with bariatric patients have delivered some sessions by telephone (Kalarchian et al., 2012; Gade et al., 2015); however, this was the first published study to examine an exclusively telephone-based CBT intervention. The empirical findings and feedback from participants suggest that CBT is feasible to deliver by telephone and helpful to bariatric patients.

The strengths of this research include the RCT design, use of a treatment manual, novel method of treatment delivery, and use of validated assessment tools. However, a discussion of the study limitations is warranted. First, weight was not included as an outcome variable so it is not possible to determine whether Tele-CBT has a beneficial impact on weight loss. Second, the questionnaires were completed immediately following Tele-CBT and additional research is needed to determine if pre-operative Tele-CBT leads to greater improvement in eating psychopathology and psychosocial functioning following surgery. Third, 30% of participants in the current study discontinued Tele-CBT, and the lengthy Tele-CBT sessions may have impacted attrition.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the current pilot RCT provided preliminary support that a 6-session pre-operative Tele-CBT intervention is feasible, and appears efficacious in improving eating psychopathology and depression immediately following the intervention. These pilot findings lend support to the growing body of literature demonstrating that CBT can be a helpful tool for bariatric surgery patients and provide an impetus to investigate other novel methods of treatment delivery to increase accessibility to psychosocial interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant #317877) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sarah Royal for conducting Tele-CBT with a subset of the participants and Vincent Santiago for assisting with the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BES

Binge Eating Scale

- EES

Emotional Eating Scale

- GAD-7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale

- SF-36

Short-Form 36 Health Survey

- Tele-CBT

Telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.001.

References

- Abiles V, Abiles J, Rodriguez-Ruiz S, Luna V, Martin F, Gandara N, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy on weight loss after two years of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese patients. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2013;28:1009–1114. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.4.6536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. The emotional eating scale: the development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;18:79–90. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199507)18:1<79::aid-eat2260180109>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton K, Drerup M, Windover A, Heinberg L. Brief, four-session group CBT reduces binge eating behaviours among bariatric surgery candidates. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2009;5:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton K, Heinberg L, Windover A, Merrell J. Positive response to binge eating interventions enhances postoperative weight loss. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2011;7:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck NN, Johannsen M, Stoving RK, Mehlsen M, Zachariae R. Do post-operative psychotherapeutic interventions and support groups influence weight loss following bariatric surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DS, Vithiananthan S, Thomas JG, Trautvetter J, Unick JL, Jakicic JM, … Wing RR. Bari-active: a randomized controlled trial of a preoperative intervention to increase physical activity in bariatric surgery patients. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2015;11:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassin SE, Sockalingam S, Wnuk S, Strimas R, Royal S, Hawa R, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for bariatric surgery patients: preliminary evidence for feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice. 2013;20:529–543. [Google Scholar]

- Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310:2416–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade H, Friborg O, Rosenvinge JH, Småstuen MC, Hjelmesæth J. The impact of a preoperative cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on dysfunctional eating behaviours, affective symptoms and body weight 1 year after bariatric surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity Surgery. 2015;25:2112–2119. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1673-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviours. 1982;7:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD. Psychosocial interventions pre and post bariatric surgery. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015;23:457–462. doi: 10.1002/erv.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Courcoulas AP, Cheng Y, Levine MD, Josbeno D. Optimizing long-term weight control after bariatric surgery: a pilot study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2012;8:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.04.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WC, Engel SG, Elder KA, Chapman WH, Eid GM, Wolfe BM, et al. Walking capacity of bariatric surgery candidates. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2012;8:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara MD, Baker MT, Larson CJ, Mathiason MA, Lambert PJ, Kothari SN. Travel distance, age, and sex as factors in follow-up visit compliance in the post-gastric bypass population. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2005;1:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, Parikh JA, Dutson E, Mehran A, … Gibbons MM. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22:70–89. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman EJ, Simon GE, Tutty S, Von Korff M. A randomized trial of telephone psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: continuation and durability of effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:257–266. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, Pereja BC, Callejas F, Pereja JC. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Obesity Surgery. 2008;18:648–651. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meany G, Conceicao E, Mitchell JE. Binge eating, binge eating disorder, and loss of control eating: effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. European Eating Disorders Review. 2014;22:87–91. doi: 10.1002/erv.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, … Brethauer S. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obesity. 2013;21:S1–S27. doi: 10.1002/oby.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, Catledge C, Honos-Webb L, Vella L, et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Likosky W, Bertagnolli A, Goodkin DE, Van Der Wende J, Dwyer P, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioural therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlhans B, Horbach T, De Zwaan M. Psychiatric disorders in bariatric surgery candidates. A review of the literature and results of a German pre-bariatric surgery sample. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31:414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obesity: Guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment, and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children (NICE clinical guideline 43) London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzul KB, Jackson T, Crawford S, Kwong JC, Sockalingam S, Hawa R, … Okrainec A. Understanding disposition after referral for bariatric surgery: when and why patients referred do not undergo surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2014;24:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph A, Hilbert A. Post-operative behavioural management in bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity Reviews. 2013;14:292–302. doi: 10.1111/obr.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets C, Peat C, Berg K, White E, Bocchieri-Ricciardi L, Chen E, et al. Post-operative psychosocial predictors of outcome in bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2015;25:330–345. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1490-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam S, Cassin SE, Crawford S, Pitzul K, Khan A, Hawa R, et al. Psychiatric predictors of surgery non-completion following suitability assessment for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB The Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder – the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutty S, Ludman EJ, Simon G. Feasibility and acceptability of a telephone psychotherapy program for depressed adults treated in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutty S, Sprangler DL, Poppleton LE, Ludman EJ, Simon GE. Evaluating the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural teletherapy in depressed adults. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Kelle SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston: The Health Institute: New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wells AM, Garvin V, Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH. Telephone-based guided self-help for binge eating disorder: a feasibility study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;21:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(1997)21:4<341::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- Papalazarou A, Yannakoulia M, Kavouras SA, Komesidou V, Dimitriadis G, Papakonstantinou A, et al. Lifestyle intervention favorably affects weight loss and maintenance following obesity surgery. Obesity. 2010;18:1348–1353. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]